Digital Governance and Collaborative Strategies for

Improving Service Quality

Michael E. Milakovich

Department of Political Science, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, U.S.A.

Keywords: Digital Governance, Collaborative Model, Information Communication Technologies (ICTs), Paradigm

Shift, Benchmarks, Performance Management, E-Governance, Social Networking, Voting Advice

Applications (VAAs), Open Government, Connected, Citizen Participation, Co-Production of Services.

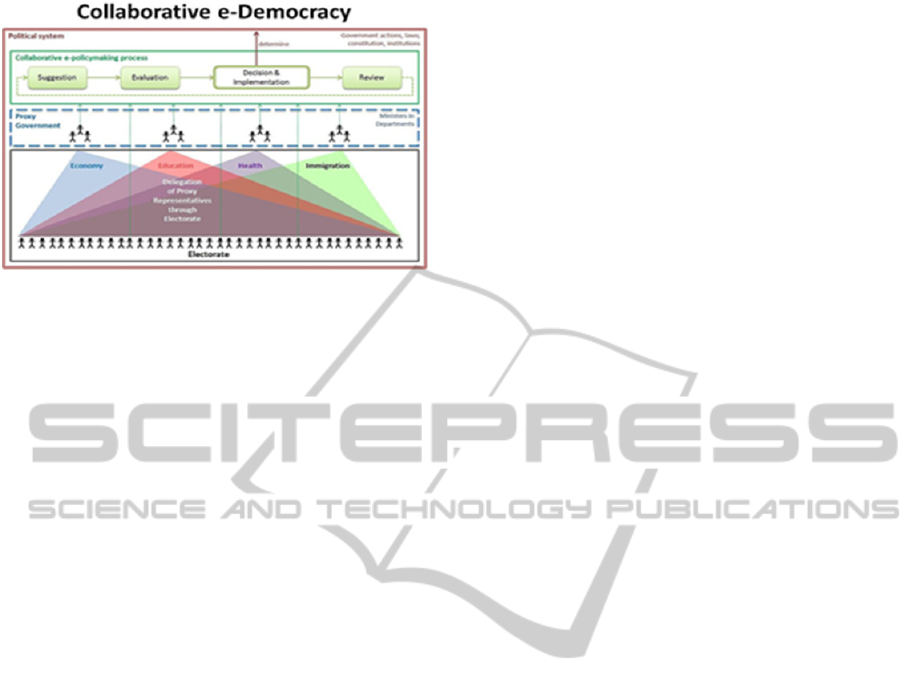

Abstract: This paper explores changes in traditional political linkages and argues for greater use of a collaborative

model (Figure 2) for achieving citizen access with information communication technologies (ICTs). There

is substantial evidence that a ‘paradigm’ shift from bureaucracy-driven electronic to collaborative digital

governance is taking place. Common factors which encourage or limit adoption of ICTs by governmental

agencies include public administrators’ distrust of non-professionals, government officials’ fear of loss of

control, lack of sufficient funding. Prospects for the future expansion of digital governance to deliver higher

quality less costly government services in the current strict fiscal environment are assessed. The paper

highlights case studies of emerging applications in selected cities and states where advanced ICT

applications are being used to achieve operating efficiencies, program effectiveness, and productivity.

Examples are given which can serve as ‘benchmarks’ for collaborative reforms. Digital governance

strategies can promote both the politics and performance management potential for technological

collaboration well as improve access to and satisfaction with government services. Emerging collaborative

relationships among governments and public as well as private agencies not only result in a more efficient

service delivery, but also lead to more accountable and interoperable administrative structure.

1 FROM E-GOVERNMENT AND

E-GOVERNANCE

Digital technologies are increasingly important in

lowering the cost and improving the quality of all

types of public services (Dunleavy, Margetts,

Bastow, and Tinkler, 2006; Milakovich, 2005; Obi,

2007; West, 2005). New technologies, however, do

not self-implement. In order to be successfully

applied, proposed technological changes must be

framed within collaborative strategies designed to

promote information sharing, partnerships, and

uniform standards (Agranoff and McGuire, 2006;

O’Leary, Gerard, and Bingham, 2006; Tang and

Tang, 2014). Methodologies for achieving these

goals differ from agency to agency, from country to

country and from region to region. They range from

incremental to radical changes in governmental

workforces and information technology systems.

Digital governance offers a strategic framework for

designing and implementing new paradigms to shift

from bureaucracy-based (Figure 1) to citizen-

centered public service (Xu, 2012). The

collaborative model (Figure 2) differs from other

reforms by emphasizing data sharing,

interoperability, system integration and results-

orientation (Milakovich, 2012a).

Figure 1.

109

E. Milakovich M..

Digital Governance and Collaborative Strategies for Improving Service Quality .

DOI: 10.5220/0005021001090118

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2014), pages 109-118

ISBN: 978-989-758-050-5

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Figure 2.

Since the beginning of the information revolution, e-

government concepts have been adopted by many

governments worldwide. Early design concepts such

as Customer Relationship Management (CRM) and

Total Quality Management (TQM) were drawn from

commercial business applications and applied to

government agencies. The World Bank (2014)

defines e-government as “analogous to e-commerce,

which allows business to transact with each other

efficiently (B2B) and brings customers closer to

businesses (B2C), e-government aims to make the

interaction between government and citizens (G2C),

government and business enterprises (G2B), and

inter-agency relationships (G2G) more friendly,

convenient, transparent, and inexpensive.”

Electronic government can be understood as a means

to better serve citizens through economical and

efficient devices and services.

Governance is the legal obligation of duly-elected

government entities to exercise authority over

citizens within their jurisdictions, such as police

power, policy-making, goal setting, performance

management and regulation. UNESCO (2011)

defines e-governance as “the public sector’s use of

information and communication technologies with

the aim of improving information and service

delivery, encouraging citizen participation in the

decision-making process and making government

more accountable, transparent and effective.” E-

governance differs from standard governmental

decision-making by engaging citizens in a wider

range of governing processes through the extended

use of information and communication technologies

(ICTs). The difference between e-government and e-

governance is that “e-government refers to the usage

of ICT as tools that will allow the State to

communicate with its citizens, and the States’

agencies between them. [E]-governance refers to

ICTs used in order to boost the active participation

of the citizens in the political procedures of their

country, giving a channel to ‘hear their voice’ in a

dynamic process of continuous feedback” (Obi,

2007: 29). In an external environment where ICTs

are restructuring nearly every aspect of a society,

government must enter the electronic world

complying with the rules and principles of e-

governance to electronically execute its functions.

With the rapid deployment of ICTs, more and more

words have added a prefix “e”, such as e-mail, e-

government, which generally refers to ICTs applied

to deliver a particular function. Digital governance

differs substantially from electronic governance.

2 DIGITAL GOVERNANCE

Digital governance is an objective or a further result

evolving from government’s progress towards

implementation of e-governance. Electronic

governance is the preliminary stage of combining

government functions with electronic devices so that

citizens are better able to increase both the depth and

breadth of contacts with government agencies

electronically. Digital governance should “provide

government services that don’t simply fit within a

read-only paradigm of interactions between citizens,

government officials and government sources of

information, but to allow a paradigm that achieves

more interactive, process-oriented dissemination and

viewing of government information” (McIver and

Elmagarmid, 2002: 10). Therefore, digital

governance plays a greater role in designing a

strategic framework in which a more citizen-

centered public service can be ensured and more

democratic government-citizen relationships will

emerge.

Digital governance is the networked extension of

ICT relationships to include faster access to the web,

mobile service delivery, teleconferencing, and multi-

channel information technology to achieve higher

levels of two-way communication. It encourages the

use of Google+, Skype, Face Time and other two-

way direct communications to facilitate the co-

production and delivery of government services

between citizens, business partners and public

employees (Milakovich, 2010). Digital governance

combined with the Internet and social networking

apps has the potential to transform the basic nature

of public service and government-citizen

relationships.

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

110

3 FACTORS ENCOURAGING

DIGITAL GOVERNANCE AND

SOCIAL NETWORKING

Traditional public agencies are governed by

hierarchical, linear, top-down communication styles

maintaining distance between citizens and public

officials. Citizens only receive services between 9

AM and 5 PM, when most are working. Darrel West

pointed out nearly a decade ago that IT has the

potential “to substantially redistribute power,

functional responsibilities, and control within and

across federal agencies and between the public and

private sectors” (West, 2005: 5). Digital

technologies are transforming public agencies into

flatter and nonlinear citizen-centric organizations

fostering more interactive relationships with affected

citizens using network-based systems and database-

driven analytics software. New types of

organizations are seeking to delegate decision-

making to socio-algorithmic forms of power that

have the capacity to predict, govern and activate

learners' capacities and subjectivities (Williamson,

2014: 12) Digital technologies are also accessible

24/7, capable of enhancing communication by

overcoming distances in both time and space—

encouraging bureaucrats to work collaboratively

with citizens.

In addition, digital technologies can promote

participatory democracy for larger numbers of

citizens. E-democracy can also be defined as the use

of ICTs and strategies by democratic actors (e.g.

government, elected officials, the media, political

organizations, citizens/voters) within governance

processes of local communities, nations and on the

international stage (Milakovich, 2010). E-democracy

can and should be measured by the level of e-

participation, because levels of citizen’s

participation in political and governance processes

are an effective measure of participatory democracy

(Klofstad, 2011). This includes applications of new

social networking websites such as Linked-In,

Facebook and Twitter. Online applications and

social networking websites have the further potential

to contribute to even more extensive development of

e-participation.

Social networking applications enable more

individuals and groups to participate in a greater

variety of online political activities, such as

acquiring and sharing political information,

discussing political issues in online forums and

engaging in political campaigns. In addition, some

countries already allow their citizens to vote online.

In a recent paper, Alvarez, Levin, Trechsel, and

Vassil, introduced a new type of web application:

Voting Advice Applications (VAAs), which can be

used to “match voters to the party or candidate

representing their optimal choice, based on

information provided by the individual and parties,

and an algorithm used to compute issue distances;

VAAs subsequently offer “voting advice” consisting

of a list of candidates ranked in terms of their

distance to the user” (Alvarez, et.al., 2012: 1).

VAAs have been developed for elections taking

place in individual countries as well as for region-

wide European Union elections. However, VAA

users are more likely to be younger, higher educated,

and have higher income levels. VAAs are more

likely to affect the choices of those who have not yet

developed strong partisan attachments, as well as

individuals with lower levels of education (Vassil

2011).

The importance of social networking in promoting

political activities is widely recognized, if not yet

well understood. There is a growing assortment of

social networking websites which are used as often

for “info-tainment” as they are for connectivity and

communication. What is distinct about social

networking websites, as compared to other types of

media and Internet services, is that they can establish

online relationships based on existing social

networks, clustered around groups of people who

already know each other (Boyd, 2008). Therefore,

social networking websites can be powerful tools for

reinforcing and promoting users’ existing political

views. Social media may also serve as alternative

service delivery networks for cash-strapped

government agencies.

Prior to the invention and widespread use of

Internet-enabled new media devices such as mobile

cellular smart phones, iPads, and Global Information

Systems (GIS), access to big datasets and broadband

applications were only available to a limited number

of experts and institutions. The Internet facilitates

collaborative applications by simultaneously acting

as a low-cost worldwide broadcasting network, a

platform for information dissemination and

propaganda, and a medium for interaction among

individuals and groups via computers, laptops,

mobile phones—without regard for geographic

boundaries or time zones. Social networking

applications have broadened the base for sharing

ideas and political partisanship with others. For

instance, Facebook pages are used mainly for

businesses, individuals, organizations and brands to

DigitalGovernanceandCollaborativeStrategiesforImprovingServiceQuality

111

share their stories and connect with other like-

minded groups or persons. The main function of the

page is the feed or the "wall," where users can

publish messages, share links, and tag photos.

Parviainen, Poutanen, Laaksonen, and Rekola

(2012), measured activity and friendship

connections on Facebook, and analyzed candidate

supporters’ political behavior during the Finnish

presidential elections. In 2011, they found that

Internet penetration had reached 89% of the total

population. Moreover, 47% of Finns registered with

a social networking service, and 49% searched for

information on political parties or candidates online

(Parviainen, et. al., 2012). This study implies that

activity on political pages is linked to the

connectedness of the users generating the content.

These findings better explain why online civil

society and digital town squares have become new

arenas for political competition (Newsom and

Dickey, 2013).

The predictive results and future implications of this

apparent ICT trend could be utilized to understand

and possibly predict patterns of political activity on

social media. Moreover, ICTs are capable of

creating closer links between government officials

and citizens because both groups can more easily

participate through multiple channels.

Citizen participation is at the very foundation of

democracy in the United States and other Western

Democracies. According to Florini “information is

the lifeblood of both democracies and markets”

(2002: 3). Digital governance strategies facilitated

by ICTs and social networking sites have make it

easier for citizens to search public records from

government websites, discuss political issues in an

internet forum, and scrutinize government actions

through retrieval of records from databases. ICTs

can also broaden access so that more citizens are

better able to participate in democratic processes,

especially for excluded groups, such as the poor,

disabled and handicapped. The participatory model

been reinvigorated in recent years by the Obama

administration’s Open Government (2012) and

ConnectED (2013) initiatives encouraging citizens’

input in governance and technologically-based

learning. Digital technologies increase opportunities

to go beyond traditional forms of citizen

participation such as debating issues, seeking

information, and voting online. The increasing

pervasiveness of digital social media in the last

decade has also dissolved many past technical

barriers preventing widespread and sustained citizen

involvement in actually co-producing and co-

delivering public services.

Pioneering initiatives,

in turn, are also thawing cultural barriers

between public administrator professionals to

collaboratively engage in co-designing public

services with non-expert citizens.

Higher levels of e-participation may bring deeper

levels of knowledge about political processes and

encourage participatory democracy. For those with

access to ICTs, e-collaboration can help citizens

become more personally informed and better

capable of checking and balancing decision-making

processes. In this way, government becomes

increasingly transparent. E-participation enables

citizens’ voices to be heard more clearly and

frequently, which encourages willingness to engage

into decision-making process, and enhances greater

certainty about individual political efficacy. Since

the early 1980s, academics have recognized that

aspirations for citizen participation in government

should go beyond merely contributing to policy

formulation processes; it should extend to the

delivery of public service programs as well

(Whitaker, 1980). Recognition that the delivery of

services could include citizen participation is

reflected in the long history of citizen involvement

as interns, jurors and volunteer firefighters, self-

management of community centers, and

neighborhood watch programs. The newly

recognized techno-enhanced phenomenon of co-

delivery is increasingly being adopted in the private

sector in many ways, including the use of online

banking, ATM machines and self-service gas

stations. Many of the routine functions of

government could similarly be converted to mobile

service delivery.

4 DIGITALLY ENHANCED CO-

PRODUCTION OF SERVICES

Since the late 1990s, advances in technology have

allowed more governments to apply new approaches

to more actively engage citizens in the design,

delivery and co-production of public services. An

early trend was the creation of self-service

opportunities for citizens to find information or

complete a service transaction online, including

availability of Congressional issue briefs, payment

of bills or drivers’ license renewals. In the most

recent rendition of this concept, two-way

information and communication technologies such

as live chat sites are being used to complete complex

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

112

licensing and registration transactions online. Wired

public officials are available via two-way video to

assist citizens in the co-delivery of services and by

helping to complete transactions with government

agencies without having to wait in line during office

hours.

The IBM Center for Business and Government

highlighted three different types of co-delivery

initiatives that can increase citizen engagement, each

offering different roles and opportunities for citizens

to engage in public services: co-design, co-

production, and co-delivery of public services

(Kannan and Chang, 2013).

Co-design initiatives. These allow citizens to

participate in the development of a new policies

or services. Initiatives are typically time-bound

and involve citizens either individually or as a

group. For example, the development of the

Obama administration’s Open Government

policy in 2009 engaged citizens via an open

electronic platform where citizens could be

actively involved in the drafting of policy

guidance.

Co-production initiatives. Involves citizens—as

individuals or in groups—in creating a service

to be used by others. These can involve either

short-term or long-term participation. For

example, the Youth Court of Washington, D.C.

engages first-time, non-violent offenders to

serve as a jury and try other offenders as a

teaching tool to reduce the chances of

recidivism. Similarly, the U.S. Patent and

Trademark Office engages individual outside

experts in the patent application examination

process to speed patent issuance (Simone-

Novack, 2009. In contrast, the Library of

Congress engages large groups of citizens via

crowdsourcing to classify and categorize

content and facilitate appropriate information

retrieval for all users.

Co-delivery initiatives. Also involves citizens—

as individuals or in groups—in delivering a

service to others. It can be premised on either

short-term, transaction based or longer-term

relationships. The United Kingdom has been a

pioneer in co-delivery of health and mental

health programs, including family intervention

programs and community support programs

(Kannan and Chang: 2013).

Despite these advances, traditional bureaucratic

systems still present barriers to expanding the use of

collaboration, co-delivery and pro-active

approaches. Among them: 1) public administrators’

distrust of non-professional citizens’ 2) government

officials’ fear of loss of control; and 3) lack of seed

funding (Bovaird and Loeffler, 2012). However, a

clearer understanding of different engagement

strategies and their value and potential limitations

can help lower some of these barriers, especially in

cases where government leaders are willing to pilot

the adoption of these new operating approaches.

Chief among the obstacles to further expansion is

the realization that it is generally easier to apply

technological innovation than it is to make the

administrative and political changes necessary for its

implementation and utilization. Technology has

important objective capacities, but it also influences

employee behavior, organizational structures, social

interactions, and institutional responsiveness.

Plainly, the skills necessary for meaningful use of

ICTs may be more constraining than access to the

technology (Mossberger, Tolbert, and Stansbury,

2003).

5 FACTORS LIMITING ICTS’

ADOPTION IN FEDERAL,

STATE, AND LOCAL

AGENCIES

Despite electoral successes and promises of reform,

public administrators (the much maligned ‘action’

side of government) often lack the capacity,

competence and motivation to breakthrough

ingrained administrative processes. Without

systematic reforms of current structures of

government bureaucracy and additional training in

the use of human capital, government workforces

may not be up to the challenge of creating the tech-

savvy workforce envisioned and funded by Obama

administration. The pace of change is also affected

by an agency’s political willingness to change.

Political motivation is typically guided by

administrative-legislative relationships.

Digital technologies have been used in the past two

American presidential election cycles to encourage

otherwise non-involved but tech-savvy voters to

participate in elections by direct contact with like-

minded friends and information sharing with the

candidates (Milakovich, 2010). Federal agencies

have encouraged similar changes to deliver public

services, but have just begun to use ICTs to achieve

them. What factors limit adoption in federal, state

DigitalGovernanceandCollaborativeStrategiesforImprovingServiceQuality

113

and local agencies? Heeks and Bhatnagar (1999)

suggested that there are several barriers to successful

technological implementation: technical, people,

management, process, cultural, structural, strategic,

political and environmental. More recently,

Goldfinch (2007) identified four implementation

problems: over-enthusiasm, unrealistic assumptions

about organizational control, lack of valid

performance indicators and benchmarks, and lack of

public accountability through inappropriate

contracting out of technology.

Darrell West posed the question, what drives the

speed and breadth of technological change? He

pointed out the pace and breadth of change is

affected by factors such as “the nature of work

routines within bureaucratic agencies and the degree

to which the organization is open to change”

(2005:12). Bureaucrats are notoriously suspicious of

change and often choose to slowdown the

dissemination of new technology by resisting

standardization and rational innovation.

Public administration may have to reassess the

classic theory of incrementalism. First proposed by

Charles A. Lindblom 55 years ago, it has become the

operating manual of how most public agencies

should make decisions (Lindblom, 1959).

Incrementalism is a model of decision making

through the use of limited successive comparisons

focusing on simplifying choices and ‘muddling

through’ rather than maximizing outcomes. In sharp

contrast, most new technological applications

require changes in the status quo and more precise

decision-making methodologies. Bureaucrats may be

forced to streamline data collection processes,

change internal structures, and re-organize external

relationships among organizations.

The decision to fully adopt a complex ICT social

networking project requires governments to make a

long-term commitment rather than a series of

successive incremental allocations. Frequent

elections, changes in office-holders, lack of

expertise, and shifts in political priorities and

budgetary preferences work against a consistent

focus and momentum to complete ICTs projects.

6 ACCESS, DATA ANALYSIS

AND COLLABORATION

Nearly all governments are under severe short-term

budgetary and fiscal pressures brought on by

revenue constraints resulting from weakness in the

economy. This has also widened the gap between

citizens with access to digital technology and those

without (Dijk, 2005). The digital divide affects 62

million Americans and reflects economic inequality

between groups, broadly construed, in terms of

access to, use of, or knowledge of ICTs. Knowledge

of computers and Internet use are divided along

demographic and socioeconomic lines, with

younger, more affluent and better educated citizens

more likely to enjoy the benefits of connectivity.

Thus, factors such as age, illiteracy and poverty

become barriers to receptivity of digital

technologies. Unless and until this knowledge

barrier is eliminated, there is a significant risk that

those most in need services may become those least

able to access them in a new world of technological

discrimination.

Similarly, within an organization, there is also a

digital divide among human assets, which results

from differences in employees’ ages, education

backgrounds, and cultural diversity. Generational

differences within workforces may lead to conflict,

frustration, and poor morale for some workers, while

at the same time those very differences could inspire

increased creativity and productivity for others. For

example, younger New Millennial workers prefer to

use email to contact colleagues, while more senior

Baby Boomers still use telephones to contact others.

Highly educated technological experts hired by

public agencies bring technological reform into

organizations, but others with basic educational

experience have to accept re-training in order to

adapt to new digital systems.

Emerging globalization trends and the openness of

the Internet bring together elites from all over the

world into organized activities. The emergence of

global elites which control nearly one-half the

world’s wealth lessens the potential for

democratizing political processes (Hindman, 2009).

Furthermore, different languages, value systems, and

uneven awareness of the importance of digital

technologies could further hinder progress.

Organizations converting to the digital governance

model must take cultural diversity into

consideration. Developing a common platform

equipped with a uniform language for interaction,

clarifying organizational cultures, and

accommodating differences, increases the

probability that organizations will reduce digital

divides resulted from poverty and cultural diversity.

Collaborative strategies among diverse public

agencies are vital in successfully moving from

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

114

bureaucracy-driven to data-driven strategies.

Performance management strategies can and should

be used to reinforce core performance values (e.g.

cost reduction, efficiency, results-measurement,

satisfying external customers, and teamwork) and

make necessary program adjustments (Milakovich

and Gordon, 2013). Governments generally fall

behind the private sector in managing performance

because they rely on “lagging indicators” and

obsolete data collection centers to evaluate agency

performance. To help improve agency effectiveness,

managers need real-time data. Governments at all

levels need to rely more on continuous data review,

which allows them to perceive problems

immediately and take actions in time to prevent

them from becoming unmanageable (Milakovich,

2012b). However, few public administrators, and

ever fewer elected officials, have access to statistical

skills and relevant case examples necessary to fully

utilize information available from burgeoning cloud-

based mega-databases. Additional expertise is

needed to implement advanced data collection and

analysis.

Public organizations of all types may be

overwhelmed by the vast amounts of different types

of data requiring real-time processing. They need to

build the capability for analyzing more and different

kinds of data in order to take advantage of the big

data opportunity. Moreover, the timeliness of

processing unstructured sources is also an important

factor. Coping with mega data effectively requires

performing data mining in real time rather than after

it has been collected and stored (Milakovich,

2012b). This may require contracting with outside

expertise, specialists in concentrating multiple data

points into decision-able analysis. Collaboration

with the private sector is also more common, with

businesses entering into myriad new arrangements,

contracts, partnerships and cooperative agreements

with providers where risks and rewards are shared

and the focus of both parties is less on partisanship

than on delivery of improved results. Unlike

outsourcing models of the past, digital governance

strategies are designed to achieve genuine

collaborative partnerships that go beyond merely

installing information technology—rather they

encompass all activities necessary to provide needed

assets and services.

In government, efforts such as these are too often

viewed as crisis interventions rather than

comprehensive collaborative performance

management strategies. Bretschneider (1990) partly

explains why nurturing genuine collaborative

partnerships is a challenge for government: the

authority of the public organization derives in part

from legal and constitutional arrangements

embedded with traditional checks and balances

causing greater interdependence across

organizational boundaries. Greater interdependence

leads to higher levels of oversight rather than

collaboration. In addition, a more cooperative

relationship among business entities results from the

fact that private firms are driven by the overarching

goal of maximizing profits. Public organizations are

not profit-driven and frequently have multiple,

complex, and sometimes competing or conflicting

organizational goals (Thomas & Jajodia, 2004). This

pronounced difference between private and public

sectors also makes it harder to initiate, organize, and

apply an enterprise-wide ICTs projects.

Despite numerous efforts to enhance communication

and collaboration among governments at all levels,

public agencies have relied principally on single

sources of data which are no longer sufficient to

cope with the increasingly complicated problems.

Linkages between different data sets are occurring

and will continue in the future. This helps to

increase interoperability between agencies at

different levels. Traditional bureaucratic concepts of

data ownership are being challenged and new

models drawn from multiple data pools are being

established. With the help of ICTs, public service is

no longer wedded to older models of citizen-official

interaction. Interactions can be customized based on

citizens’ needs and preferences (Ho, 2002).

Electronic sharing of data among agencies is

improved in the name of preventing counter-

terrorism and protecting homeland security, and

lessons learned from these applications are being

transferred to other governmental functions. Several

states and local governments have converted

traditional bureaucracy-centered systems to newer

citizen-centered, cloud-enhanced and networked

governance.

7 FEDERAL, STATE AND LOCAL

BENCHMARKS

Among the obstacles to data-ready cloud computing

is reconciling the customer service model with rigid

federal and state cost-allocation rules for funding IT

systems that operate social services, transportation,

public safety and health care. In recent years, a

growing number of U.S. states as well as numerous

DigitalGovernanceandCollaborativeStrategiesforImprovingServiceQuality

115

localities have moved their data systems and

applications from expensive regional data centers

into the information technology cloud. Texas signed

a series of multiyear data center service contracts,

outsourcing the state's massive data management

needs. Minnesota finished moving almost 40,000

workers in more than 70 state agencies to

Microsoft's cloud-based software program for email

services and collaboration tools. Colorado has

moved its 26,000 member workforce to Google's

suite of office applications. My Maine Connection,

created by the Maine Department of Health and

Human Services in partnership with the state’s e-

government portal provider, Maine Information

Network, provides a one-stop portal for citizens to

determine eligibility and apply for Maine's food,

medical and temporary families and child-care

assistance programs. This service can also work on

mobile devices. The program “telemedicine” in

Alaska ensures citizens’ accesses to quality health

care by overcoming the extreme climate, state’s

geographic factors, and the lack of infrastructures in

remote areas. This tele-health system allows

providers in local village clinics to collect patient

information into an electronic case and to transmit

the case to medical specialist as remote location via

a secure network.

Government-initiated citizen participation efforts

have begun to evolve beyond listening and

responding to complaints. Newer applications are

aimed at efforts at greater engagement, such as the

use of e-petitions, GPS systems and citizen reporting

of street-level service problems (Lipsky, 1980).

Mobile telephone cameras enable citizens to provide

real-time feedback to public authorities responsible

for crime control, fire prevention, and public safety.

Many federal and some state and local agencies are

pioneering new initiatives as well, such as the

“citizen archivist” role at the National Archives and

Records Administration in Washington, where

citizens can help digitize the Archive’s paper

records, identify ancestors in old photographs, and

transcribe handwritten Civil War diaries.

New York City has transformed software from

reactive systems responding to problems as they

occur to proactive systems which enable officials to

integrate databases, discover and address problems

before they happen. Residents may contact either

911 or 311 or submit photos or videos via smart

phones to a call-center to record their complaint.

Bicyclists can summon police directly by taking

pictures of motorists blocking bike lanes. New York

City uses comprehensive metrics collected from

both citizens and public officials to measure just

about everything, from emergency assistance calls to

bike paths; from tree plantings to detailed, agency-

specific indicators. In addition, the New York Fire

Department utilizes big data to help predict where

fires will occur by cataloguing over 60 factors that

make fires more likely to occur, such as average

neighborhood income, the age of the building, and

whether or not the buildings have electrical issues.

Fire inspections are then prioritized based on “risk

scores” generated by an algorithm (Dwoskin, 2014).

The Information Security Cloud of New York City

uses real-time analytic data to identify and analyze

malware on site.

The City of Los Angeles and the software

development company CGI implemented a web-

based Financial Management System across 42 city

departments, replacing the city’s three aging legacy

systems and seven other redundant systems. Its

benefits such as dashboard analytics, reporting and

tracking, real-time budgetary information, “E-

approvals,” and automated past-due billing

processes improve the city’s cash flow. Nevada

County, California, using “community of interest”, a

way of grouping departments with related mission

for broad-based analysis of technology needs and

solutions, transitioned its technological governance

from one centered on the perceived needs of

individual departments to one integrating

technological needs across the entire enterprise.

8 TOWARDS A

COLLABORATIVE DIGITAL

FUTURE

As the pace of technological applications quickens at

all levels of government, more individuals and

organizations are likely to experience both the

benefits as well as the risks inherent in mega data

collection. Indeed, as suggested earlier in this paper,

internet technology may be transforming the nature

of government itself, but not necessarily in positive

ways. Public accountability is a primary concern not

always shared by private data gathering and

information storage companies. Under some

circumstances, populations are seen as disaggregated

sets of sub-populations with different risk profiles

rather than a single unified social body.

Extraordinary measures must be taken to protect the

integrity, privacy and security of data collection and

storage.

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

116

Whether or not a collaborative approach will be

accepted by government to improve service quality

initiatives is still an open question, one without a

simple yes or no answer. Change-oriented

governments and support organizations must adopt

new methods of training to accommodate the needs

of multiple groups and interests in order to

encourage collaboration and enhance performance

and productivity. Digital divides within

organizations and among the most vulnerable

citizens must be overcome. How these inequalities

are dealt with, how skills are learned—and how they

can be applied to various functions at different levels

of government—will determine how case study

evidence is used to equalize access to the Internet,

enhance political connectivity and promote better

customer service based on improved data collection,

analysis and collaboration.

REFERENCES

Agranoff, R. and M. McGuire. (2004) Collaborative

Public Management: New Strategies for Local

Governments. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown

University Press.

Alvarez, R.M., Levin, I., Trechsel, A. H., Vassil, K.

(2012). “Voting Advice Applications: How Useful?

For Whom?” Paper delivered at St. Anne’s College,

Oxford University, October, 2012.

Bretschneider, S. (1990). “Management Information

Systems in Public and Private Organizations: An

Empirical Test.” Public Administration Review, 50,

(5): 536-545.

Boyd, D. (2008). “Can Social Networking Sites Enable

Political Action?” Chapter in A. Fine, M. Sifry, A.

Raseij, & J. Levi (Eds.), Rebooting Democracy. New

York: Personal Democracy.

Bovaird, T, and Loeffler. E. (2012). “From Engagement to

Co-Production: the Contributions of Users and

Communities to Outcomes and Public Value.” ISTR,

Voluntas, 23:1119–1138.

Dijk, J.A.G.M.V. (2005). The Deepening Divide:

Inequality in the Information Society. Thousand Oaks,

CA.: Sage Publications.

Dunleavy, P., Margetts, H., Bastow, S., & J. Tinkler.

(2006). “New Public Management Is Dead: Long Live

Digital-Era Governance. Journal of Public

Administration Research the Theory, 16 (3): 467-494.

Dwoskin, Elizabeth (2014). “How New York’s Fire

Department Uses Data Mining.” http://blogs.wsj.com/

digits/2014/01/24/how-new-yorks-fire-department-

uses-data-mining/?mod=WSJBlog

Florini, A.M. (2002). “Increasing Transparency in

Government,” International Journal on World Peace,

19 (3): 3-37.

Goldfinch, S. (2007). “Pessimism, Computer Failure, and

Information Systems Development in the Public

Sector.” Public Administration Review, 67 (5): 917–

929.

Hindman, M (2009). The Myth of Digital Democracy.

Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press.

Ho, A.T. (2002). “Reinventing Local Governments and

the e-Government Initiative.” Public Administration

Review, 62 (4): 434-444

Heeks, R., & Bhatnagar, S. (1999). “Understanding

Success and Failure in Information Age Reform.” (pp.

49-74). In R. Heeks, (Ed.), Reinventing Government in

the Information Age: International Practice in IT-

Enabled Public Sector Reform. London, UK:

Routledge.

Kannan, P.K. and Chang, A. M. (2013). Beyond Citizen

Engagement: Involving the Public in Co-Delivering

Government Services. Report by IBM Center for

Business and Government. Retrieved at

www.businessofgovernment.org

Klofstad, C.A. (2011). Civic Talk: Peers, Politics and the

Future of Democracy. Philadelphia: Temple

University Press.

Lindblom, C. (1959). “The Science of ‘Muddling

Through,’” Public Administration Review, 19(4): 79-

88.

Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas

of the Individual in Public Services. New York: Sage

Publishers.

McIver, William J. Elmagarmid, Ahmed K. (2002).

Advances in Digital Government: Technology, Human

Factors, and Policy. Hingham, MA, USA: Kluwer

Academic Publishers.

Milakovich, Michael E. (2005). Improving Service Quality

in the Global Economy. New York: Auerbach

Publications, Taylor and Francis.

Milakovich, M. (2010). “The Internet and Increased

Citizen Participation in Government,” Journal of

EGovernment and EDemocracy, 1 (2): 1-9.

Milakovich, M. (2012a). Digital Governance: New

Technologies for Improving Public Service and

Participation. London and New York: Rutledge.

Milakovich, M. (2012b). “Anticipatory Government:

Integrating Big Data for Smaller Government,” Paper

delivered at St. Anne’s College, Oxford University,

October, 2012.

Milakovich, M. and G. J. Gordon (2013). Public

Administration in America (11th ed.) Boston: Cengage

Learning.

Mossberger, K, Tolbert, C.J., and Stansbury, M, (2003).

Virtual Inequality: Beyond the Digital Divide.

Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Newsom, G. and L. Dickey (2013). Citizenville: How to

Take Town Square Digital and Reinvent Government.

New York: Penguin Press.

“Obama Administration Unveils “Big Data” Initiative:

Announces $200 Million in New R&D Investments,”

(2012) White House Office of Technology Policy,

Executive Office of the President, March 29, 2012.

DigitalGovernanceandCollaborativeStrategiesforImprovingServiceQuality

117

Obi, Toshio (Ed.) (2007). E-Governance: A Global

Perspective on a New Paradigm. Amsterdam, Berlin,

Oxford, Tokyo, Washington, DC: IOS Press.

O’Leary, R, C. Gerard, and L. Bingham, (2006).

“Introduction to the Symposium on Collaborative

Public Management. Special Issue.” Public

Administration Review, 66: 6-9.

Parviainen, O., P. Poutanen, R. Laaksonen and S., Rekola, M.

(2012). “Measuring the Effect of Social Connections on

Political Activity in Facebook,” Communication

Studies, Department of Social Research, University of

Helsinki.

Simone-Novak, B. (2009). Wiki Government: How

Technology can make Government Better, Democracy

Stronger, and Citizens More Powerful. Washington,

D.C.: Brookings Institution.

Tang, C. P. and S.Y. Tang. (2014) “Managing Incentive

Dynamics for Collaborative Governance in Land and

Ecological Development.” Public Administrative

Review, 74 (2): 220-231.

THE WORLD BANK. (2014) Website retrieved at

http://www.worldbank.org/

Thomas, G.A., & Jajodia, S. (2004). “Commercial Off-

the-Shelf Enterprise Resource Planning Software

Implementations in the Public Sectors: Practical

Approaches for Improving Project Success.” Journal

of Government Financial Management, 53 (2): pp. 12-

18.

UNESCO (2011) Retrieved at: http://portal.unesco.

org/ci/en/ev.php-URL_ID=3038&URL_DO=DO_

TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

U.S. Department of Commerce, National Telecom-

munications and Information Administration (NTIA).

1995. Falling through the net: A survey of the "have

nots" in rural and urban America. Retrieved from

http://www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/fallingthru.html

Vassil, Kristjan. (2011). Voting Smarter? The Impact of

Voting Advice Applications on Political Behavior.

PhD Dissertation. European University Institute.

West, D.M. (2005). Digital Government: Technology and

Public Sector Performance. Princeton University

Press: Princeton and Oxford.

Whitaker, G. (1980). “Coproduction: Citizen Participation

in Service Delivery,” Public Administration Review,

40 (3): 240-246.

Williamson, B. (2014). “Governing Software: Networks,

Databases, and Algorithmic Power in the Digital

Governance of Public Education,” Learning, Media,

and Technology, 39 (3):1-23.

Xu, H. (2012). “Information Technology, Public

Administration, and Citizen Participation: The Impacts

of E-Government on Political and Administrative

Processes.” Public Administration Review, 72, (6)

915–920.

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

118