Knowledge Management Problems in Healthcare

A Case Study based on the Grounded Theory

Erja Mustonen-Ollila

1

, Helvi Nyerwanire

1

and Antti Valpas

2

1

Department of Software Engineering and Information Management,

Lappeenranta University of Technology, Lappeenranta, Finland

2

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, South Karelia Social and Health Care District, South Karelia, Finland

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Healthcare, Empirical Research, Case Study, Grounded Theory.

Abstract: Knowledge management describes how information communication technology systems are applied to

support knowledge creation, as well as in the capturing, organization, access, and use of an organization’s

intellectual capital. This paper investigates knowledge management problems in healthcare. The major

conclusions regarding the problems identified are: access to patient data in ICT systems or lack of data,

complex medical data, and problems in saving data to ICT systems; ICT system integration, architecture,

cost and regulations by political decisions and knowledge transfer problems; tacit knowledge missing in

ICT systems; communication and communication barriers between primary and special healthcare; ICT

security and trust problems; negative attitude or limited support from "peers" or superiors; patients’

resistance to recommendations; physicians’ stress and control-sharing problems, too short time in the

policlinic to search for patient information, limited personnel resources, and work pressure. A conceptual

framework of knowledge management is developed by the Grounded Theory approach. The data validates

past studies, and reveals relationships between categories. The relationships between the knowledge

management categories enhance confidence in the validity of the categories and relationships, and expand

the emerging theory.

1 INTRODUCTION

The concept of healthcare, as referred to in our

study, includes medicine, nursing, and rehabilitation

(Koskinen, 2010). In this study the healthcare

environment is referred to as a place in which

medical, clinical and nursing knowledge is ingrained

in practitioners (Räisänen et al., 2009). Knowledge

refers to the ways that information can be made

useful to support a specific task or make a decision

(Stair and Reynolds, 2006), personalized

information (Alavi and Leidner, 2001), awareness,

experience, skills, and learning (Suurla et al., 2002),

tacit knowledge (Polanyi, 1966; Nonaka, 1994),

explicit knowledge (Puusa and Eerikäinen, 2010;) as

well as the medical, clinical, and nursing knowledge

of physicians and nurses (Hill, 2010). Knowledge

management is defined as a process where

information communication technology (ICT)

systems are applied to support the activities in

organizing knowledge, expertise, skills and

communication (Suurla et al., 2002). Knowledge

management can be further defined as a

collaborative and integrated approach to the

creating, capturing, organizing, access and use of an

organization’s intellectual capital (Dalkir, 2005).

There exists collective knowledge in organizational

networks (Alavi and Leidner, 2001), and people

learn by working with each other in practice, and

transfer and receive knowledge on best practices

(Grover and Davenport, 2001). In spite of the above

definitions and past studies, there are several

problems that hamper knowledge management.

These problems include communication and

understanding problems between ICT professionals

and healthcare professionals (Martikainen et al.,

2012). One reason for this communication problem

can be the fact that the working communities do

different things and work differently, they have

different terms and vocabularies, and therefore they

do not understand each other (Dalkir, 2005).

Viitanen et al. (2011) argue that physicians have

problems with searching for the right data. The

patients’ resistance to recommendations, limited

15

Mustonen-Ollila E., Nyerwanire H. and Valpas A..

Knowledge Management Problems in Healthcare - A Case Study based on the Grounded Theory.

DOI: 10.5220/0005028200150026

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2014), pages 15-26

ISBN: 978-989-758-050-5

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

time and limited personnel resources, work pressure,

negative attitude or limited support from "peers" or

superiors can be causes for not following the

guidelines (Heilmann, 2010). Using the ICT system

can also take a lot of physicians’ work time, they

have problems with accessing patient data, and they

are highly critical towards ICT systems (Martikainen

et al., 2012; Nykänen et al., 2012). Finally, Kothari

et al. (2012) claim that physicians’ and nurses’ tacit

knowledge cannot be found in ICT systems.

As past studies have shown, a lot of knowledge

management problems exist in healthcare. We have

applied past studies and empirical evidence to carry

out a qualitative in-depth case study (Benbasat et al.,

1987; Yin, 2003) that identifies problems in

knowledge management in one healthcare

environment. We analyze the collected data with the

Grounded Theory (GT) approach, and develop a

conceptual framework with categories and

relationships between the categories (Glaser and

Strauss, 1967; Pawluch and Neiterman, 2010). Our

goal is to investigate knowledge management

problems in detail in a Social and Health Care

District and its central hospital, both located in

South Karelia, Finland. We explore strategies that

healthcare organizations deploy while learning about

their knowledge management problems, to what

extent these problems are shaped by the

organizational context, and how these potential

problems influence both ICT system development

work and patient care work in practice. We have

made 103 knowledge management observations

supported by empirical evidence.

We categorized the observations with GT

analysis (Glaser and Strauss, 1967), and the analysis

revealed 23 categories: Patient, Patient Data in ICT

Systems, Patient Data Transfer in ICT, Patient Data

Transfer on Paper, Lack of Patient Data Transfer

Control, Permission Denial of Patient Data Transfer,

Patient Care Process, Nurse, Nurse’s Lack of Time,

Physician, Physician’s Attitudes, Physician’s Stress,

Physician’s Lack of Time, Physician’s Tacit

Knowledge, Physician’s Medical and Clinical

Decisions, ICT Systems, ICT Systems Vendor, ICT

Systems Legislation, ICT Systems Technology, ICT

Systems Development Resources, ICT Systems

Communication Barriers, Primary and Special

Healthcare Services, and Social Issues.

The above categories were related to each other,

and we found six higher levels of abstraction of

statements based on our conceptual framework,

propositions to our categories, and relationships

between the categories.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows.

Section two describes related research, section three

presents the research method, and section four

outlines the data analysis. Finally, section five

contains conclusions and discussion.

2 RELATED RESEARCH

According to Fisher (2013), healthcare ICT systems

contain too much data, and the healthcare

professionals are not able to find the required

information and data of the patients. Viitanen et al.

(2011) and Martikainen et al. (2012) also claim that

it is difficult to find the previous patient records

because the search functions in the ICT systems and

their usability are poor. Physicians and other

healthcare professionals have difficulties in finding

the relevant data on time, they do not know what

kind of data to search for, and they are critical

towards ICT in general (Martikainen et al., 2012;

Nykänen et al., 2012; Viitanen et al., 2011). The

contextual aspects behind ICT system design are

difficult to understand, and therefore there is a

problem of how to involve healthcare professionals

in ICT system development activities. There are also

problems to visualize which different technologies

can be integrated together in ICT, and how to use

healthcare professionals’ knowledge in ICT

(Martikainen et al., 2012). When physicians are

requested to participate in healthcare ICT system

development, they find such activities quite pointless

(Martikainen et al., 2012). Viitanen et al. (2011)

claim that ICT systems lack suitable features to

support typical clinical decision-making, and ICT

systems are not able to provide the physicians with

the features and functionalities which are required to

perform clinical work on patients, for example to

analyze the state of the patient, make decisions about

the actions required, and perform the actions.

Young et al. (2000) state that junior physicians miss

proper ICT systems, which are robust, time neutral,

and need a short time to learn, because they need

ICT systems frequently in their work. Greig et al.

(2012) claim that it is difficult to share knowledge

and to know what knowledge exists in the working

organizations because the access is restricted.

Furthermore, verbal knowledge in mentoring and

formal or informal meetings is not stored in ICT

systems (Lin et al., 2008). It is not always known,

either, what other colleagues have not written down

in the ICT system (Nykänen et al., 2012). Kothari et

al. (2012) claim also that the tacit knowledge of

healthcare professionals is not found in ICT systems.

Accordingly, ICT systems, guidelines and divisions

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

16

of work, specializations, organizational structures,

cultural models and attitudes vary between public

primary, private primary and special healthcare

service environments (Viitanen et al., 2011).

Burgess et al. (2012) state that information transfer

and communication between primary and special

healthcare services fail. Primary healthcare takes

place in municipal health centres, private clinics,

working places, schools, and defence forces. These

organizations have their own type of patients and

only if the patient requires special healthcare, she or

he is guided to it, such as to a central hospital or

university hospital (Niskanen, 2002). One problem

is that proper coordination tools, such as medical

information about the patient in ICT systems

between private health centres and public healthcare

are lacking, and information is transferred on paper

or by fax, and some important data can be lost when

transferring it (Reddy et al., 2009). There is no

control in data transfer, and the staff must start the

programs manually (Häyrinen et al., 2008). The

healthcare ICT systems are expensive, regulated by

political decisions, not standardized, include

complex medical data, it is difficult to save data to

the systems and do statistics, and there exist security

and trust problems (Grimson et al., 2000). There are

also problems in integrating the separate ICT

systems in social care and healthcare because of the

laws concerning them (Niskanen, 2002; Laki

159/2007, 2007; STM, 2013). The systems are not

standardized, and healthcare organizations are

forced to take new versions of systems in use

regularly (Laki 159/2007, 2007; STM, 2013).

Central governments are shifting the social and

healthcare laws to local authorities in order to

arrange better social and healthcare for the citizens,

and healthcare service systems are divided into

primary, special healthcare, tertiary healthcare and

social services, which are supervised by the

municipal authorities of social and healthcare

districts. In Finland these services are supported by

the National government (Hämäläinen et al., 2013).

Finally, the integration of ICT systems is not

prepared for the future needs of patients (Linthicum,

2004). One problem is that patients will advise or

guide physicians towards other options for their

condition, and this will cause stress to the physicians

(Edwards et al., 2012). According to Blakeman et al.

(2006), physicians have problems in patient care

with patient involvement and sharing the control of

the patient’s health. Ammenwerth et al. (2006) state

that a physician has too short time in the policlinic to

search for patient information in the systems, and he

or she does not want to move back and forth

between systems, as for instance the X-ray pictures

have to be looked at in viewers. According to Gupta

(2009), integration is difficult due to a lack of

integration standards, and hospitals have currently a

lot of computer systems installed or built at various

periods of time by different vendors. Suomi and

Salmivalli (2002) argue that in paper-form

prescriptions one of the biggest problems is the

difficulty of reading the physician’s handwriting.

Kaye et al. (2010) claim that the barriers between

primary and special healthcare services are lack of

knowledge and skills, and poor communication. The

barriers are a result of non-recognition of health

professionals’ roles and responsibilities, and

inadequate communication between primary and

special healthcare services. One problem and

challenge in managing resources and service

improvement is due to complex healthcare

operations if an enterprise architectural solution is

missing, and the ICT systems’ architectural

descriptions within organizations lack the three

layers of business, application and technology

(Jonkers et al., 2003). Nilakanta et al. (2009) also

claim that business processes are more important

than clinical and diagnostics care, and knowledge

management capabilities and the organization’s

commitment and focus on knowledge support the

business processes. Thus, despite a growing interest

in knowledge management problems in healthcare,

their relationships have not been recognized in the

literature. Rather, past studies have focused on

knowledge management problems and ICT systems

in healthcare in general. Therefore, our study aims to

respond to this lack of studies and to provide useful

information of knowledge management in one

Social and Healthcare District and its central

hospital. Based on the past studies, we have

formulated the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the knowledge management

problems in healthcare?

RQ2: How are the knowledge management

problems in healthcare related to each other?

3 RESEARCH METHOD

This study utilizes both qualitative and quantitative

research processes and theory building approaches.

It takes an in-depth case study, theory building and

Grounded Theory (GT) perspective involving a

specific healthcare environment in which knowledge

management problems are studied (Glaser and

Strauss, 1967; Benbasat et al., 1987; Eisenhard,

1989; Yin, 2003; Cresswell, 2007; Pawluch and

KnowledgeManagementProblemsinHealthcare-ACaseStudybasedontheGroundedTheory

17

Neiterman, 2010). In this healthcare environment,

the case was selected so that it would either predict

similar outcomes (i.e. literal replication) or produce

contracting results but for predictable reasons (i.e.

theoretical replication) (Yin, 1994). Theory

triangulation was applied by interpreting a single

data set from multiple perspectives to understand the

research problems (Denzin, 1978). The concepts and

their relationships were validated with the grounded

theory approach (Glaser and Strauss, 1967;

Eisenhardt, 1989; Glaser, 1992). During the

research, theoretical background knowledge was

gained, which increased the credibility of the study

(Glaser, 1992; Miles and Huberman, 1994).

According to Eisenhardt (1989), the combination of

case study with the grounded theory approach has

three major strengths: it produces a novel theory, the

emergent theory is testable, and the resultant theory

is empirically valid. In the GT approach the theory

emerges from the data. According to Glaser (1992),

there is no need to review any literature of the

studied area before entering the field. This is in line

with our research, as we started collecting the data

before developing our conceptual framework.

Specifically, each interview transcript was analyzed,

and major emergent themes and concepts were

identified in order to form similar categories (Myers

and Avison, 2002). In our case study, a social and

healthcare district and its central hospital were the

units of analysis. The sample was limited to one

district and its central hospital, because the goal of

the study was to gain deep understanding of the

selected environment and to identify the knowledge

management problems at this specific site. The

target of the study was the Social and Healthcare

District of South Karelia in Finland and its central

hospital (Timonen, 2013; Eksote, 2013). The district

has about 133 000 inhabitants, and the total number

staff employees in the district is 3 843, of which

1 711 work in the health services. In the central

hospital, 17 special medical areas cover scheduled

clinical appointments in ward care, urgent care and

emergency. The number of scheduled clinical visits,

urgent care and emergency is approximately over 80

000 a year (Timonen, 2013; Raudasoja, 2013;

Eksote, 2013).

The knowledge management definitions and

objectives of the research formed the basis for

interviews and data collection. The interviewees

were also presented with the research problem, and

they were chosen because their role was to use,

create and transfer healthcare-related medical and

ICT information, and translate it to knowledge

relevant to the healthcare situation at hand. In order

to address the research questions, we conducted

seven audio-recorded unstructured and semi-

structured interviews that investigated experiences in

knowledge management issues in the chosen

healthcare environment. The interviews included

three individual interviews and four group

interviews, and they took place between June 2012

and November 2013. The interviewees were the

communications manager, ICT director, the central

hospital’s medical director (who was also the chief

physician in the internal medicine and

endocrinology department), the central hospital’s

chief physician in the obstetrics and gynaecology

department, the central hospital’s junior physician in

the emergency department of the district, and the

development manager of the National Archive of

Health Information (KanTa Services) project (STM,

2013) of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

The interviewees had been involved in many

knowledge management issues and processes in

their own fields of expertise during their working

careers that extended over a period of 10 to 30 years

in different positions either in South Karelia Social

and Health Care District or other healthcare

environments in Finland. The development manager

of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health was

interviewed about the past and future health

development in Finland, because the KanTa project

(STM, 2013) affects the healthcare development in

all social and healthcare districts in Finland.

Archival material was also studied, representing a

secondary source of data, and it included public

news and internal material of the development of the

Social and Health Care District, and public news of

the KanTa project of the Ministry of Social Affairs

and Health. Triangulation involved checking

different data sources simultaneously to improve the

reliability and validity of the data.

3.1 Data Collection and Categorization

The interviews included frequent elaboration and

clarification of the meanings and terms, they were

audio-recorded, and the recordings were transcribed,

yielding over 100 pages of transcripts. After

transcribing the interviews, we categorized the data

under the main categories, knowledge management

problems according to relevant terminology and

theories, which were the most often refereed work of

categorizing concepts in the studied research area.

The problem with the main categories was whether

there would be enough proof found in the data to

derive the knowledge management categories as

valid and reliable, and whether the categories

discovered in the data would be the correct ones.

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

18

Table 1: Categories and total number of different empirical observations.

Category Definition

Total

number of

observations

Patient A patient receives care and treatment by a physician. 42

Patient Data in ICT Systems

Patient’s personal data, medical history, treatments, tests, examinations,

diagnoses, and consultation requests in the ICT systems.

16

Patient Data Transfer on

Paper

Patient’s personal data, medical history etc. are transferred on paper. 7

Patient Data Transfer in ICT Patient’s personal data, medical history etc. are transferred in ICT systems. 6

Lack of Patient Data Transfer

Control

In many ICT systems’ areas the transfer of the patient’s personal data,

medical history etc. is not controlled and the staff must start the programs

manually.

3

Permission Denial of Patient

Data Transfer

A patient can deny her or his personal data, medical history etc. to be

transferred with ICT or on paper.

2

Patient Care Process

In the patient care process a physician makes a diagnostic decision and

determines the proper treatment for the patient.

8

Physician

A physician needs knowledge of anatomy, physiology, and medical science

and knowledge of how to apply this knowledge in practice.

17

Physician’s Tacit Knowledge

A physician’s tacit knowledge is related to how she or he is able to use his or

her biomedical knowledge, intuition and experience.

4

Physician’s Attitudes to ICT

and Patients

Physicians' attitudes towards ICT systems are negative because of lack of

time. Physicians have attitude problems towards patients who know about

their own diseases.

4

Physician’s Stress Patients cause stress to physicians. 2

Physician’s Medical and

Clinical Decisions

ICT systems do not support the clinical and medical work of the physician. 5

Physician’s Lack of Time Physician has lack of time in the policlinic to search for patient information. 2

ICT Systems

There are hundreds of ICT systems used in hospitals, which physicians and

other professionals use in their daily work with patients.

31

ICT Systems Vendor ICT systems’ vendor implements the ICT systems and ICT products. 7

ICT Systems Technology

ICT system technology connects the healthcare treatment process in which

different people and technologies work together.

19

ICT Systems Legislation

The laws prevent the integration of social and healthcare issues in ICT

systems. The social and healthcare laws have been transferred from the

Finnish national government to local authorities.

4

ICT Systems Development

Resources

System developers are not qualified enough to implement ICT systems to

healthcare due to their lack of training in biomedical informatics. ICT

development lacks money.

4

ICT Systems Communication

Barriers

The barriers between primary and special healthcare services and ICT

professionals are lack of knowledge and skills, and poor communication.

1

Nurse

Nurses work together with physicians, therapists, other healthcare staff,

families and patients.

6

Nurse’s Lack of Time

Nurses are busy, and do not have enough time to input data to the ICT

systems.

6

Primary and Special

Healthcare Services

Healthcare guarantees sufficient social and healthcare services for all

residents in the district.

4

Social Issues Patient’s social issues. 3

Total number of

observations

103

Table 2: An example of an observation concerning the category “Physician’s Tacit Knowledge”.

Knowledge

management problem

Definition Source Empirical evidence

Interviewed

person,

specialized

area/ expertise

Physicians have to

interpret the results

of special tests by

special devices by

themselves using

their tacit knowledge

The ICT systems are not able to

provide the physicians the features

and functionalities which are

required to perform clinical work

on patients, for example to analyze

the state of the patient.

Puusa and

Eerikäine

n, 2010;

Heilmann;

2010;

Hill, 2010

For example, in special treatment, the

information systems may control some

devices like the x-ray machine, e.g. by

collecting the data and analyzing it. Then

the doctor has to make the analysis of what

the data is, and then write it down to the

main system.

Junior

physician,

specializing in

gynecology

and women's

diseases

KnowledgeManagementProblemsinHealthcare-ACaseStudybasedontheGroundedTheory

19

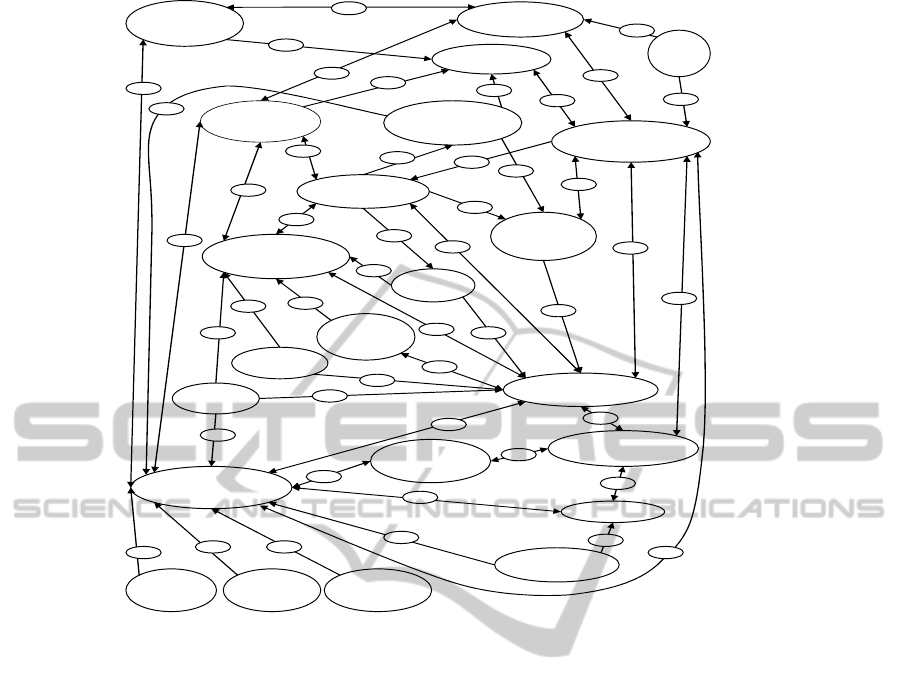

Figure 1: Conceptual framework of categories.

Based on our intuition and knowledge we made a

table 1. In table 1 the first column includes a specific

knowledge management problem discovered in the

empirical data; the second column includes the

definition of a knowledge management problem

based on the empirical data; the third column

includes evidence from the literature to the problem

in the first column; the fourth column includes the

name of the literature source of the third column;

and finally the fifth column includes the transcript

number and the interviewed person’s name and

occupation. By doing this we have created a chain of

evidence: from empirical data we have derived all

the knowledge management problems and validated

them with past studies. This table is available on

separate request from the authors.

4 ANALYSIS

After creating the chain of evidence in data

categorization, a total amount of 103 different

empirical observations under 23 categories (see

Table 1) were found by using Glaser and Strauss’s

(1967) and Pawluch and Neiterman’s (2010)

grounded theory analysis instructions, which support

the finding of categories grounded on data and based

on the researchers’ own intuition and knowledge. An

example of an observation concerning the category

“Physician’s Tacit Knowledge” is presented in Table

2.

Our conceptual framework of the discovered

categories (see Figure 1) is based on empirical

evidence and theories reflecting the findings in the

field (Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Pawluch and

Neiterman, 2010). Specifically, we have involved

fragmentation and reassembled our data into

thematic categories by trying to capture a broader

social system of ideas from the experience of the

social actors (Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Pawluch and

Neiterman, 2010), in this case the actors working in

the Social and Health Care District. After the

categories had been found, we determined the

properties of the categories and propositions

(hypotheses) for how the categories were related. In

Figure 1, the categories are shown as ellipses, and

the solid, numbered arrows describe the

relationships between the categories. These

relationships based on empirical data are presented

in detail in Table 3.

Nurse’s

Lackof

Time

PatientDatain

ICTSystems

PatientData

TransferinICT

LackofPatient

DataTransfer

Control

PermissionDenial

ofPatientData

Transfer

Physician’s

Tacit

Knowledge

Physician’s

Attitudes

Physician’s

Stress

Physician’s

LackofTime

Physician’sMedical

andClinical

Decisions

ICT

Systems

Ve

n

do

r

ICTSystems

Legislation

ICTSystems

Technology

ICTSystems

Development

R

esou

r

ces

SocialIssues

ICTSystems

Physician

Patient

PrimaryandSpecial

Healthcare Services

PatientCareProcess

Nurse

PatientData

Transferon

Paper

ICTSystems

Communication

Barriers

13

34

33

17

6

42

41

16

44

9

43

46

2

39

22

27

1

15

47

26

32

21

5

8

45

29

30

11

10

31

24

25

28

20

23

19

14

37

38

40

36

12

24

1835

7

3

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

20

Table 3: Properties of categories and propositions (hypotheses) on how the categories are related on the basis of the data.

Category/Categories

Properties of categories and propositions (hypotheses) on how

the categories are related (arrows in Figure 1)

Arrow

number

Patient Data in ICT Systems, Patient, Nurse,

Physician, ICT systems, Physician’s Medical

and Clinical Decisions

Physicians and nurses must document all care treatment in order

to follow up how the patient has been treated.

1, 2, 3,

4, 5

Patient Data Transfer in ICT, Patient, Patient

Care Process, Primary and Special Healthcare

Services

The patient moves back and forth between primary and special

healthcare services, because the patient data does not move

between services.

6, 7, 8

Patient Data Transfer on Paper, Patient, Patient

Care Process, Physician, Primary and Special

Healthcare Services, ICT System

Communication Barriers, ICT Systems

Primary and special healthcare services transfer patient data on

paper not by ICT systems even if they use the same ICT systems.

9, 7, 8,

10, 11,

43, 46

Patient Data Transfer in ICT, Lack of Patient

Data Transfer Control

It is possible that other complications will appear because the

data transfer is not controlled.

13, 14

Lack of Patient Data Transfer Control, ICT

Systems, Patient Data in ICT Systems, Patient

Data Transfer in ICT

In ICT systems’ areas data is distributed between heterogenic

and autonomous ICT systems, and there is no data transfer

control.

14, 41,

42

Permission Denial of Patient Data Transfer,

Patient, ICT Systems

The denial of patient information permission affects the ICT

system architecture, and data transfer is restricted.

15, 16,

17

Patient Care Process, Physician, Patient, Patient

Data in ICT Systems, Primary and Special

Healthcare Services

Physicians cannot track a patient’s location in the patient care

process in the ICT systems because of a large amount of data.

18, 7, 2,

1, 19, 45

Primary and Special Healthcare Services,

Patient Care Process, Patient, Physician

Right healthcare is not provided by the health centers and thus

the patients need hospital care.

19, 8, 7,

2

Physician’s Tacit Knowledge, Physician’s

Medical and Clinical Decisions, ICT Systems

A great deal of tacit knowledge is not transferred from healthcare

professionals via ICT systems to other healthcare professionals.

20, 21,

22, 23

Physician’s Tacit Knowledge, Physician, ICT

Systems

Healthcare professionals use “tricks” called as hidden knowledge

in ICT systems and computers.

20, 23

Physician’s Attitudes, Physician’s Medical and

Clinical Decisions, ICT Systems, Patient,

Physician

Junior physicians have attitude problems to patients who know

about their own diseases. The healthcare personnel’s attitudes

towards ICT systems are negative.

24, 25,

26, 27

Physician’s Stress, Patient, Physician’s Medical

and Clinical Decisions, Physician

Patients cause stress to the physicians by giving them advice

about their illnesses.

2, 28,

29, 30

Physician’s Lack of Time, Physician’s Medical

and Clinical Decisions, Patient Data in ICT

Systems, ICT Systems, Patient, Physician

Physicians have too short time in the policlinic to search for the

patient data in the ICT systems and other special systems and

devices.

31, 32,

22, 23

ICT Systems, Physician’s Medical and Clinical

Decisions, Patient, Physician

ICT systems do not guide medical decision-making. 23, 5, 27

Nurse’s Lack of Time, Nurse, Patient Care

Process, Patient

Physicians and nurses do not have enough time to input data to

ICT systems.

33, 34,

3, 47

ICT Systems Vendor, ICT Systems

The ICT vendor has problems in the change management of ICT

systems, and it takes years to implement the changes.

35

ICT Systems, ICT Systems Legislation, Social

Issues

Integration of social and healthcare issues in ICT systems is not

possible because of laws.

36, 37,

38

ICT Systems, ICT Systems Legislation, ICT

Systems’ Technology, Social Issues

Psychosocial support for the future needs of a patients is missing

from ICT systems and their integration.

36, 37,

38, 12

ICT Systems, ICT Systems Technology

The usability of ICT systems is poor because of many new ICT

versions, and too much unnecessary data must be saved in the

ICT systems.

12, 39

ICT Systems, ICT Systems Technology, ICT

Systems’ Vendor

It means huge work to implement a new interface to an old

fashioned application environment (ICT system environment).

12, 35

ICT Systems, ICT Systems Development

Resources

Qualified ICT personnel who know about biomedical knowledge

in the healthcare ICT systems area is lacking due to the growing

importance of ICT system integration.

40

ICT Systems, ICT Systems Communication

Barrier, Primary and Special Healthcare

Services

A knowledge and communication barrier exists between primary

and special healthcare services for patients. Communication and

understanding between ICT professionals and healthcare

professionals are poor.

11, 10,

ICT Communication Barrier, Primary and

Special Healthcare Services, Social Issues, ICT

Systems, ICT Systems’ Legislation

Laws regulate the communication of ICT systems between social

workers and healthcare patients with social problems.

36, 11,

10, 38

KnowledgeManagementProblemsinHealthcare-ACaseStudybasedontheGroundedTheory

21

Finally, in our in-depth case study, we took carefully

into consideration beforehand who to interview,

what to do next, what group to look for, and what

additional data we should collect in order to develop

a theory from the emerging data. The constant

comparison between the data and concepts in past

studies in order to accumulate evidence convergence

on simple and well-defined categories led us to a

higher level of abstraction of statements about the

relationships between the categories. This theorizing

was in line with Pawluch and Neiterman’s (2010)

suggestions of creating a grounded theory with

Glaser and Strauss’s (1967) approach. The higher

level of abstraction of the statements is presented in

the conclusions and discussion section.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND

DISCUSSION

This qualitative, empirical case study based on the

Grounded Theory approach (Glaser and Strauss,

1967) revealed that many knowledge management

problems can be found in knowledge and

information-intensive environments in the healthcare

domain. Based on seven in-depth interviews, the

study described knowledge management problems in

the South Karelia Social and Health Care District in

Finland and its central hospital. As the data

collection point of view we used the director level

of the central hospital, the ICT director, the

communications manager, and the junior and senior

physician level of the central hospital in the district,

as well as the development manager level of the

Ministry of Social Affairs and Health in Finland.

This multi-perspective point of view gave us rich

data for solving our research problems.

Our study is in line with the studies of

Martikainen et al. (2012), Viitanen et al. (2011),

Nykänen et al., (2012), and Fisher (2013)

concerning problems with patient data in ICT

systems. Studies of problems in ICT system

development, technologies, integration and ICT

systems’ lack of clinical decision-making

(Martikainen et al., 2012; Young et al., 2000) are

also in line with our study. The problems in

knowledge transfer and lack of data were also

verified (Greig et al., 2012, Lin et al., 2008). The

claims by Nykänen et al. (2012), and Kothari et al.

(2012) for tacit knowledge missing in ICT systems,

and the lack of data transfer control (Häyrinen et al.,

2008) were also confirmed. The claims by Polanyi

(1966), Nonaka (1994), Puusa and Eerikäinen

(2010), Heilmann (2010), and Hill (2010)

concerning the use of tacit knowledge in decision

making were also proved to be valid.

Attitude problems (Viitanen et al., 2011), failures

in information transfer, and communication and

communication barriers between primary and special

healthcare services (Burgess et al. 2012; Niskanen,

2002, Reddy et al., 2009; Kaye et al., 2010) were

also found. Difficulties in carrying out statistics

from the current data in ICT systems due to their

structure was confirmed (Grimson et al., 2000). We

also discovered that ICT systems are expensive,

regulated by political decisions, not standardized,

and include complex medical data, it is difficult to

save data to systems, and there exist security and

trust problems (Grimson et al., 2000). Integration

problems exist in healthcare and between social care

and healthcare because of laws (Niskanen, 2002;

Laki 159/2007, 2007; STM, 2013; Hämäläinen et al.,

2013; Linthicum, 2004; Gupta, 2009). Physicians’

stress and control-sharing problems (Edwards et al.,

2012; Blakeman et al., 2006) were also confirmed.

The statement of Ammenwerth et al. (2006) about

too short time in the policlinic to search for patient

information, and Suomi and Salmivalli’s (2002)

argument for paper problems were found to be valid

in our case as well. The claim for difficulties in

healthcare operations if an enterprise architectural

solution is missing (Jonkers et al., 2003) is in line

with our study. The claim of Nilakanta et al. (2009)

about business and knowledge management

processes being currently more important than

clinical and diagnostics care was corroborated. The

patients’ resistance to recommendations, limited

time and limited personnel resources, work pressure,

negative attitude or limited support from "peers" or

superiors were also confirmed (Heilmann, 2010).

In this study we discovered a higher level of

abstraction of statements based on our conceptual

framework, propositions to our categories, and

relationships between the categories as follows.

First, physicians’ tacit knowledge and experience,

technological skills to use ICT systems, and

knowledge of medical issues affect their medical and

clinical decisions, which are also affected by the

physicians' lack of time, stress and attitudes towards

patients and ICT. Second, medical and clinical

decisions are influenced by patient data in the ICT

systems, because a physician has no time to go

through every detail of the patient's past medical

history. Third, the patient data in the ICT systems is

affected by the patient her or himself, the physician,

permission denial of patient data by the patient, lack

of patient data, missing patient data, lack of patient

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

22

data transfer control, or too much data transfer

control by the laws. Fourth, the physician’s medical

and clinical decisions influence the patient care

process and patients who are affected by right or

wrong diagnoses, treatment and patient care. Fifth,

ICT systems’ communication barriers and

legislation, communication and knowledge barriers

and misunderstanding can prevent proper healthcare

of a patient, which is also affected by nurses' lack of

time and the available primary and special

healthcare services. Sixth, the ICT systems’ vendor,

technology, legislation, and lack of development

resources both at the ICT systems’ healthcare

organization and ICT system’s vendor side, together

with ICT systems’ communication barriers,

physician’s negative attitudes towards patients and

ICT systems, and reluctance to participate in ICT

systems’ development due to lack of time, combined

with lack of right medical and clinical decisions due

to lack of right data, as well as attitudes and

physician’s tacit knowledge and experience in the

decision making situation all affect patients' health

and can prevent the right patient care to be carried

out. All this also causes a lot of stress to both the

physician and the patient and forms a barrier to right

patient diagnoses and treatment. In the patient care

process, too many patients and data are directed at

the same time to one physician to be treated at a too

short notice and time. On the other hand, the ICT

systems in healthcare suffer from a lack of

resources, money and qualified personnel, and are

therefore affected by several issues at the same time.

The ICT systems also need integration and

modernization, and the ICT development personnel

needs a basic level of biomedical information

knowledge in order to understand the ICT systems in

healthcare and the healthcare professionals better,

but because of the lack of money both at the ICT

system vendors’ side and the healthcare

organization’s side, the resources must be focused

very carefully on time in order to meet the rising

costs of the patient care itself. The physicians and

nurses must also be given a basic level of ICT

education so that they are able to understand old and

new ICT systems, in addition to patients’ needs.

In our case study the purpose of the grounded

theory analysis (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) was to

find out categories and relationships between the

categories in one specific healthcare environment

with the inductive research approach. The concepts

were sharpened by building evidence from empirical

data describing the conceptual categories which

according to Glaser and Strauss (1967), and Pawluch

and Neiterman (2010) are the building blocks of the

grounded theory. Constant comparison between the

data and concepts was made so that the

accumulating evidence converged on simple and

well-defined categories. After the categories were

found, we defined the properties of the categories

and propositions (hypotheses) of how the categories

were related. In our in-depth case study, we took

carefully into consideration beforehand who to

interview, what to do next, what group to look for,

and what additional data we should collect in order

to develop a theory from the emerging data. Finally,

a conceptual framework of the categories was

developed, and the categories were grounded on

empirical evidence and theories reflecting the

findings in the field. The most fundamental

components in this conceptual framework were its

categories and the relationships between the

categories. This comparison with past studies led us

to six higher-level abstractions of statements about

the relationships between the categories. This

theorizing was in line with Pawluch’s and

Neiterman’s (2010) suggestions for creating a

grounded theory with Glaser and Strauss’s (1967)

approach. We also found empirical data which was

not supported by past studies, and we regard this

data as expansion to knowledge management in

healthcare. The expansion covers the following

issues. First, in the current ICT systems the same

patient data must be saved several times. Second, the

challenge is the attachment of private sector

admission notes (called internal referral notes or an

internal consultation request) such as X-ray pictures,

which must be sent on paper by post, or brought

along by the patient to the physician. Third, other

social and healthcare districts do not send feedback

forms about patients to the sending district of the

admission. Fourth, the guidelines about the process

are in written format, and can be viewed on web

pages (“Fair Treatment”, Käypähoito in Finnish),

but it is not known whether they are used. Fifth, the

ICT system vendors have difficulties in giving price

to the implementation and maintenance of e-services

of ICT systems. In this study, a special status in

theory building was given to the focal categories, the

social and healthcare district and its central hospital.

In our theory the ancillary category was the

knowledge management problem. We took care of

the boundary conditions in our theory creation,

because the phenomenon was so atypical that it held

only in this specific contextual healthcare

environment. Our results validated the conceptual

framework, which became the discovered theory for

the phenomenon. The data which confirmed the

emergent relationships enhanced confidence in the

KnowledgeManagementProblemsinHealthcare-ACaseStudybasedontheGroundedTheory

23

validity of the relationships. The data which

disconfirmed the relationships provided an

opportunity to expand and refine the emerging

theory. The results which did not get support from

past studies resulted in expansion to the theory. The

non-conflicting results strengthened the definitions

of our categories and the conceptual framework. The

past studies with similar findings were important

because they tied together the underlying similarities

in phenomena not associated with each other, and

stronger internal validity was achieved. There are,

however, several limitations in this study. First, we

had limited knowledge of the central hospital and

the social and healthcare district because access to

secondary sources was limited. Second, the results

may not be readily applicable to other districts and

central hospitals, as the phenomena were atypical.

Third, the use of only one social and healthcare

district and its central hospital affected our findings,

and thus generalization of the results can be difficult,

but not necessarily impossible. Fourth, we

performed a limited number of interviews, and the

nurses were not interviewed personally. Fifth, the

interviews were conducted in multiple languages,

which made the interviewing, transcribing, coding

and analyzing the material very demanding. The

translation made by the first author from one

language to another may have limited the analytical

strategies because the analysis was carried out only

of the interviews in the original material, and only

for conceptualization into the conceptual categories

and their meanings.

In the future, a large sample of data will be

collected in multiple case studies (Yin, 2003) with

several hospital departments and units of analysis

(Eisenhardt, 1989). Glaser and Strauss (1967) also

claim for both qualitative and quantitative data in

creating theory. Qualitative and quantitative data can

supplement each other and their comparison can

result in new theory.

REFERENCES

Alavi, M. and Leidner, D.E. (2001) ‘Review: Knowledge

Management and Knowledge Management Systems:

Conceptual Foundations and Research Issues’, MIS

Quarterly, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 107-136.

Ammenwerth, E., Talmon, J., Ash, J. S., Bates, D. W.,

Beuscart-Zephir, M. C., Duhamel, A., Elkin, P. L.,

Gardner, R. M. and Geissbuhler, A. (2006) ‘Impact of

CPOE on mortality rates – contradictory findings,

important messages’, Methods of Information in

Medicine, vol. 45, no. 6, pp. 586-593.

Benbasat, I., Goldstein, D.K. and Mead, M. (1987) ‘The

Case Study Research Strategy in Studies of

Information Systems’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 3,

pp. 369-386.

Blakeman, T., Macdonald, W., P., Gately, C. and Chew-

Graham, C. (2006) ‘A Qualitative Study of GPs’

Attitudes to Self-management of Chronic Disease’,

The British Journal of General Practice, vol. 56, no.

527, p. 407.

Burgess, C., Cowie, L. and Gulliford, M. (2012) ‘Patients'

perceptions of error in long-term illness care:

qualitative study’, Journal of Health Services

Research & Policy, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 181-187.

Creswell, J.W. (2007) Qualitative Inquiry and Research

Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches,

California: Sage Publications.

Dalkir, K. (2005) Knowledge Management in Theory and

in Practice, London, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann

Publisher.

Denzin, N.K. (Ed.). (1978) The research act: A theoretical

introduction to sociological methods, New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Edwards, M., Wood, F., Davies, M. and Edwards, A.

(2012) ‘The Development of Health Literacy in

Patients with a Long-term Health Condition: the

Health Literacy Pathway Model’, BMC Public Health,

vol. 12, no. 1, p. 130.

Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989) ‘Building Theories from Case

Study Research’, Academy of Management Review,

vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 532-550.

Eksote. (2013)’Etelä-Karjalan Sosiaali- ja Terveyspiiri’,

Available:

http://www.eksote.fi/Fi/Eksote/Hallinto/raportit/Docu

ments/Terveydenhuollonjarjestamissuunnitelma.pdf

[10 November 2013].

Fisher, W.G (2013) ‘Doctors are drowning in too much

data, not enough appropriate information’, MedCity

News, Available: http://medcitynews.com/2012/03/

doctors-are-drowning-in-too-much-data-not-enough-

appropriate-information/ [23 May 2013].

Glaser, B. and Strauss, A.L. (1967) The Discovery of the

Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative

Research, Chicago: Aldine.

Glaser, B.G. (1992) Emergence vs. Forcing: Basics of

Grounded Theory, Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Greig, G., Entwistle, V.A. and Beech, N. (2012)

‘Addressing complex healthcare problems in diverse

settings: Insights from activity theory’, Social Science

& Medicine, vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 305–312.

Grimson, J.,Grimson, W. and Hasselbring, W. (2000) ‘The

SI Challenge In Health Care’, Communications of the

ACM, vol. 43, no. 6.

Grover, V. and Davenport, T.H. (2001) ‘General

perspectives on knowledge management: Fostering a

research agenda’, Journal of Management Information

Systems, vol. 18, pp. 5-21.

Gupta, P. (2008) ‘IHE and CPOE: The Twine Shall Meet

for Healthcare’, SETLab Briefings, Infosys

Technologies Limited, Available: http://www.taurus

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

24

glocal.com/images/ihe-cpoe-infosys.pdf, [30 March

2014]

Heilmann, P. (2010) ‘To have and to hold: Personnel

shortage in a Finnish healthcare organization’,

Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, vol. 38, no. 5,

pp. 518-523.

Hill, K.S. (2010) ‘Improving quality and patient safety by

retaining nursing expertise’, The Online Journal of

Issues in Nursing, vol. 15, no. 3.

Hämäläinen, P., Reponen, J., Winblad, I., Kärki, J.,

Laaksonen, M., Hyppönen, H. and Kangas, M. (2013)

‘e-Health and e-Welfare of Finland: Check Point

2011’, National Institute for Health and Welfare.

Häyrinen, K., Saranto, K. and Nykänen, P. (2008)

’Definition, structure, content, use and impacts of

electronic health records: A review of the research

literature’, International Journal of Medical

Informatics, vol. 77, pp. 291-304.

Jonkers, H., Steen, M. and Bryant, B.R. (2003) ‘Towards a

Language for Coherent Enterprise Architecture

Description’, IEEE International Enterprise

Distributed Object Computing Conference (EDOC),

Brisbane, Australia.

Kaye, R., Kokia, E., Shalev, V., Idar, D. and Chinitz, D.

(2010) ‘Barriers and success factors in health

information technology: A practitioner's perspective’,

Journal of Management & Marketing in Healthcare,

vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 163-175.

Koskinen, J. (2010) ‘Phenomenological view of health and

patient empowerment with personal health record’,

Proceedings of the Well-being in the information

society (WIS) conference, Turku: University of Turku,

pp. 1-13.

Kothari, A., Rudman, D., Dobbins, M., Rouse, M.,

Sibbald, S. and Edwards, N. (2012) ‘The use of tacit

and explicit knowledge in public health: a qualitative

study’, Implementation Science, vol. 7, no. 1.

Laki 159/2007. (2007) ’Laki sosiaali- ja terveydenhuollon

asiakastietojen sähköisestä käsittelystä’, Available:

http://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2007/20070159 [10

October 2013].

Lin, C., Tan, B. and Chang, S. (2008) ‘An exploratory

model of knowledge flow barriers within healthcare

organizations’, Information & Management, vol. 45,

no. 5, pp. 331–339.

Linthicum, D.S. (2004) Next generation application

integration, Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Martikainen, S., Viitanen, J., Korpela, M. and Lääveri, T.

(2012) ’Physicians’ experiences of participation in

healthcare IT development in Finland: Willing but not

able’, International Journal of Medical Informatics,

vol. 81, no. 2, pp. 98–113.

Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M. (1994) Qualitative Data

analysis, Thousand Oaks, California: Sage

Publications.

Myers, M.D. and Avison, D.E. (ed.) (2002) Qualitative

Research in Information Systems: Review, London:

Sage Publications.

Nilakanta, S., Miller, L., Peer, A. and Boija, V.M. (2009)

‘Contribution of Knowledge and Knowledge

Management Capability on Business Processes among

Healthcare Organizations’, Proceedings of the 42

nd

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

IEEE, pp. 1-9.

Niskanen, J.J. (2002) ‘Finnish care integrated?’,

International Journal of Integrated Care, vol. 2, no. 2.

Nonaka, I. (1994) ‘A dynamic theory of organizational

knowledge creation’, Organization Science, vol. 5, no.

1, pp. 14–37.

Nykänen, P., Kaipio, J. and Kuusisto, A. (2012)

’Evalution of the national nursing model and four

nursing documentation systems in Finland-Lessons

learned and directions for the Future’, International

Journal of Medical Informatics, vol. 81, no. 8, pp.

507–520.

Pawluch, D. and Neiterman, E. (2010) ‘What is Grounded

Theory and Where Does is Come from?’, in

Bourgeault A., Dingwall, R. and De Vries. R. (ed.)

The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Methods in

Health Research, London: Sage Publications, pp. 174-

192.

Polanyi, M. (1966) The Tacit Dimension London:

Routledge.

Puusa, A. and Eerikäinen, M. (2010) ’Is Tacit Knowledge

Really Tacit?’, Electronic Journal of Knowledge

Management, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 307-318.

Raudasoja, S. (2013) ‘Eksote’s Strenght is its strong

customer orientation’, External Publication of South

Karelia and Social and Health Care District,

Available: http://www.eksote.fi [20 January 2013].

Reddy, M.C., Paul, S.A., Abraham, J., McNeese, M.,

DeFlitch C., and Yen, J. (2009) ‘Challenges to

effective crisis management: Using information and

communication technologies to coordinate emergency

medical services and emergency department teams’,

International Journal of Medical Informatics, vol. 78,

no. 4, pp. 259–269.

Räisänen, T., Oinas-Kukkonen, H., Leiviskä, K.,

Seppänen, M. and Kallio, M. (2009) ’Managing

Mobile Healthcare Knowledge: Physicians'

Perceptions on Knowledge Creation and Reuse’, in

Olla, P. and Tan, J. (ed.) Mobile Health Solutions for

Biomedical Applications, New York, New Hersey: IGI

Global, pp. 111-127.

Stair, R. M. and Reynolds, G.W. (2006) Fundamentals of

Information Systems, Boston, Mass: Thomson Course

Technology.

STM. (2013) ’Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriö.

Tietojärjestelmähankkeet: sähköinen potilasarkisto ja

sosiaalialan tiedonhallinta’, Available: http://www.

stm.fi/vireilla/kehittamisohjelmat_ja_hankkeet/tietojar

jestelmahankkeet/kysymyksia_kanta_hankkeesta#vast

aus [5 October 2013].

Suomi, R. and Salmivalli, L. (2002) ‘Electronic

Prescriptions: Developments in Finland’, In

Proceedings of the IFIP Conference on Towards The

Knowledge Society: E-Commerce, E-Business,

Kluwer, BV, E-Government, pp. 481-495.

Suurla, R., Markkula, M. and Mustajärvi, O. (2002)

’Developing and implementing knowledge

KnowledgeManagementProblemsinHealthcare-ACaseStudybasedontheGroundedTheory

25

management in the parliament of Finland’, The

committee for the future: The Parliament of Finland,

Available: http://web.eduskunta.fi/dman/Document.

phxdocumentId=gk11307104202716&cmd=download

[4 September 2012].

Timonen, T. (2013) ‘Key figures: statistics from the

hospital’, Internal Publication of South Karelia Social

and Health Care District.

Viitanen, J., Hyppönen, H., Lääveri, T., Vänskä, J.,

Reponen, J. and Winblad, I. (2011) ’Nationality

questionnaire study on clinical ICT systems proofs:

Physicians suffer from poor usability’, International

Journal of Medical Informatics, vol. 80, no. 10, pp.

708–725.

Yin, R.Y. (1994) Applications of Case Study Research,

Applied Social Research Methods series 34, Newbury

Park, London: Sage Publications.

Yin, R.K. (2003). Case study research: design and

methods. California: Sage Publications.

Young, R.J., Horsley, S.D. and McKenna, M. (2000) ‘The

potential role of IT in supporting the work of junior

doctors’, Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of

London, vol. 34, no. 4.

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

26