Re-Designing Knowledge Management Systems

Towards User-Centred Design Methods Integrating Information Architecture

Carine Edith Toure

1,2

, Christine Michel

1,2

and Jean-Charles Marty

3

1

Université de Lyon, CNRS, Villeurbanne Cedex, France

2

INSA-Lyon, LIRIS, UMR5205, F-69621, Villeurbanne Cedex, France

3

Université de Savoie, LIRIS, UMR5205, Chambéry, France

Keywords: Knowledge Management Systems, User Experience, Acceptance, Human-Machine Interactions,

Information Architecture, Enterprise Social Networks.

Abstract: The work presented in this paper focuses on the improvement of corporate knowledge management systems.

For the implementation of such systems, companies deploy can important means for small gains. Indeed,

management services often notice very limited use compared to what they actually expect. We present a

five-step re-designing approach which takes into account different factors to increase the use of these

systems. We use as an example the knowledge sharing platform implemented for the employees of Société

du Canal de Provence (SCP). This system was taken into production but very occasionally used. We

describe the reasons for this limited use and we propose a design methodology adapted to the context.

Promoting the effective use of the system, our approach has been experimented and evaluated with a panel

of users working at SCP.

1 INTRODUCTION

Knowledge books refers to a class of knowledge

management systems (KMS) that are built according

to the MASK method (Aries, 2014). They use

models of the activity field and are widely used

within companies because they promote easy search,

understanding and use of information. They also

help structuring information and documents with

hypertext links. Nevertheless, these KMS are

efficient only under some terms like effective

reading and updating of documents. (Prax, 2003)

introduces in his book several reasons of knowledge

management (KM) process failures in companies.

We can find functional problems (e.g. the system is

too complex, the system does not address users’

needs, there is poor organization of information),

management problems (e.g. there are inadequate or

non-existent change management strategies), and

even human problems (e.g. the KMS type is

inadequate to the cultural context of the company).

Some other issues are directly related to methods

used to design KMS. Indeed, KM designers first

strive to properly structure and define core concepts

and contents in order to describe them. It is only in a

second step that they focus and with less expertise,

on interfaces design and terms of interactions. Thus,

aspects like ergonomics, content organization and

indexing, KMS integration with other information

systems are much less considered. This work

proposes a design methodology to develop KMS that

meet more effectively the needs of demanding users

in businesses. We take into account the fact that the

corporate knowledge is already formalized in

models to produce knowledge books, our proposal

thus focuses on re-designing an existing KMS. Our

method integrates, in particular, user-centred design

processes and information architecture. We tested

our methodology in a real context of use so we can

fetch elements of evaluation and feedbacks.

Société du Canal de Provence (SCP) is a hydraulics

services company located in the Provence Alpes

Côte d’Azur French region. This company agreed to

participate to our study; since 1996, SCP has

massively invested in a knowledge book named

ALEX (Aide à l’EXploitation). For more than ten

years of production, the management services of the

company observed a weak use of ALEX, despite the

fact that the collaborators are really aware of the

usefulness of such a system. A preliminary study

was carried out to identify ergonomics-related

issues, difficulties in updating information and

298

Edith Toure C., Michel C. and Marty J..

Re-Designing Knowledge Management Systems - Towards User-Centred Design Methods Integrating Information Architecture.

DOI: 10.5220/0005137502980305

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2014), pages 298-305

ISBN: 978-989-758-050-5

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

access processes. This context was particularly

representative of design problems that one can

encounter when designing KMS. The general issue

we are trying to solve in this paper is how to re-

design KMS to promote their use. We propose

studying how to combine knowledge engineering

design methods, human-machine interaction design

methods and architecture of information. This article

is organized as follows: in the next section, we

introduce a number of methods that can be used for

designing; then we propose our methodology. In

section four, we describe the implementation and

how ALEX has evolved in SCP. We measured the

effectiveness of the method by conducting a user

survey. Section five draws a conclusion and

identifies areas for future research.

2 REVIEW OF THE

LITTERATURE

Research work in knowledge engineering has

enabled the development of several methods to

enhance and capitalize workers’ expertise in the

company. A more suited way to implement these

systems in an industrial context would be to consider

methodologies and techniques taking into account

the needs and expectations of employees in terms of

collaboration and communication. The fields of

Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) and Information

Architecture (IA) document the literature on these

methods.

2.1 KMS Design using Pioneering

Methods

Design methods in knowledge management aim to

formalize a set of procedures, skills, life skills, etc..,

which structure the activity in a way to make them

re-usable. The KOD method proposed by Vogel in

1988 (Ermine, 2008), focuses on modelling expert

knowledge from his free speech on his activity. It

consists of at least three steps: position of the

subject, interview and analysis. The MEREX

method (Prax, 2003) developed at Renault offers to

produce experience feedback in the form of sheets.

This sheet database is the KMS. An animation

procedure including three actors is then

implemented to keep the records up to date. The

editor, not necessarily an expert, produces sheets,

while the validator that checks the correctness of the

contents must be a domain expert; the manager

supervises the system. Methods of knowledge

engineering provide tools for the formalization and

capitalization of knowledge. They mainly involve

professionals in the field, essentially focused on the

formalization of knowledge and do not consider the

user who is supposed to interact with the system.

This positioning may hinder the effective use of

knowledge, as illustrated in the introductory section.

2.2 The Active Participation of Users in

the Design Process

The HCI field aims to study, plan and design the

modalities of interaction between the user and the

computer. The challenge is not only to produce

useful, usable and acceptable interactions but also to

improve the user experience according to its value

system, its business context and objectives. In fact,

the user experience is defined as the set of a user’s

perceptions in a situation of interaction with a

product (Garrett, 2011). These perceptions

determine the success or failure of a product. In

(Nielsen, 1993), the author defines the User-Centred

Design (UCD) as a philosophy and a design

approach where the needs, expectations and

characteristics of end users are taken into account at

every development stage of the product process.

This task can be complex since users do not

generally know what they want. (Mathis, 2011)

presents some approaches to better understand the

expectations of users and implement them in a more

effective way. The methods of Twinning (also called

Job Shadowing) and Contextual interviews are

examples of these approaches. The UCD refines the

understanding of the needs, possibilities and

limitations of the user in his/her activity and

regarding a technological proposal. It allows

designing more responsive systems for human and

organizational contexts where they are used.

2.3 Information Architecture Methods

As KMS can be considered as a class of information

systems, we sought what methods could be used to

define the way people access to information in such

systems. IA is a discipline that seeks to define how

to present information in the most appropriate

manner, depending on the future user and on the

context of use. The goal of IA is to define the form

of presentation that will make the most usable

information in terms of understandable and usable.

Thus, a good information architecture must be

searchable (the user is not confused), coherent

(semiotics adapted to the context of use), adaptable,

simple (just enough information presented), able to

Re-DesigningKnowledgeManagementSystems-TowardsUser-CentredDesignMethodsIntegratingInformation

Architecture

299

make information recommendations (Resmini &

Rosati, 2011). Different methods are proposed to

achieve these objectives. (Resmini & Rosati, 2011)

indicate taxonomic methods (identification of

hierarchical relationships and semantic similarity

between concepts), methods of Sorting Cards that

are used to identify and organize super categories

and intermediate categories, representing the major

classes of users’ needs. (Garrett, 2011) proposes a

more comprehensive conceptual framework for

structuring the design, especially suited for Web

applications. Its main feature is to separate and

coordinate the design features of the product and the

information it must take into account. This method is

based on five steps: strategy, scope, structure,

skeleton and surface. These steps describe how to

shift from abstract elements of the product design to

more concrete elements. In order to structure

information, Garrett proposes to use either a top-

down approach (based on the needs and objectives

of the system for organizing information) or a

bottom-up approach (use categories and

subcategories to organize the information).

2.4 Summary

Conventional knowledge management methods

prove less effectiveness because they often lead to

KMS that do not fit user’s expectations. We observe

companies adopting new Web 2.0 technologies such

as social networks. This is explained by the fact that

these new modes of exchange and communication

are becoming more and more casual in users lives

and they provide socialization platforms to support

business initiatives for knowledge seeking and

sharing. Moreover, the techniques of participatory

design and structuring of information provide the

means for designers to stay close to target users. We

propose in the next section, a methodology to re-

design a classical KMS, from a knowledge book to

an enterprise social network.

3 A FIVE STEP APPROACH

Companies are already aware of the importance of

formalizing the corporate knowledge and building

KMS. Most of them have already invested in these

strategies but could get neither a really usable

system nor a system accepted by the collaborators.

This is why we propose a re-designing approach

based on an existing knowledge capitalization. Our

approach is inspired by the conceptual framework of

(Garrett, 2011) and consists of five phases operating

tools and methods from the KM, the user-centred

design and information architecture. The steps are

cyclic and may overlap if needed. At the end of a

cycle, an evaluation of the resulting prototype is

carried out and can lead to a redefinition of the

previous choices.

3.1 Needs Analysis

In this step, we propose to analyse the initial

situation of the KMS, the users’ needs and the

system objectives. This information gathering allows

us to work on capitalized knowledge, the business

context and the expectations of the users and of the

company. The objective is to observe difficulties of

the users in front of the existing KMS and find

appropriate solutions. For a knowledge book, it is

interesting to observe users’ reaction in front models

of organization, media or forms of navigation.

Concerning the other aspects, an immersion in the

industrial environment is required; matching

methods and contextual interviews are appropriate

means to understand the environment of use and the

needs (Mathis, 2011). In addition, the method of

mind-mapping (Prax, 2003) can help to better

understand the business vocabulary through games

characterization. These studies are useful to classify

the important business concepts into categories and

super categories that will help us to structure the

information in step 3.

3.2 Definition of the New KMS

This step is used to define the features for managing

knowledge (information sharing, information

seeking, collaboration, learning) which meet the

needs. The case of SCP led us to consider the target

KMS as an enterprise social network (ESN).

Companies are increasingly interested in easy

sharing and exchanging of information via ESN

(Stocker & Müller, 2013) and look for ways to

exploit them. (Zammit & Woodman, 2013) justify

the effectiveness of ESN in knowledge management

by carrying out an analysis based on the SECI model

of Nonaka and Takeuchi. However, there is no

heuristic describing the best way to operate an ESN

as a KMS. In this stage of our method and to refine

the design choices, we recommend working in

parallel on the definition of roles and features

because these elements are essential in ESN. The

definition of roles can be done using the MEREX

method (Prax, 2003). Then one must specify, by

methods such as focus groups, the usefulness and the

format of features like members directory, news,

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

300

statistics, newsletter, photo album, dialogue groups,

events, polls, discussion forums.

3.3 Design of the Information

Structure

This step addresses the specification of interaction

formats adapted to the features and information

architecture of the system. This phase is closely

related to the results of the analysis in Phase 1. It

consists in designing patterns of interaction and

models to structure information that are familiar to

users. As the forms of interaction of the target CMS

are already pervasive in users’ habits, we

recommend keeping them. Structuring the content

on the other hand, should be investigated. Among

the two approaches proposed by Garett and

presented above, we prefer the bottom-up approach.

Indeed, a method of sorting card identifies the key

concepts as well as their different facets but also

different forms of information to be exploited.

3.4 Design of the Skeleton

This step is used to design the main functional areas

and how they are interconnected. The user-centred

method that we recommend in this step is the

definition of personas (Boucher, 2007). Personas are

virtual characters that correspond to the end users,

they allow designers to really get into the skin of end

users and make proposals that best fit them. They

are important to specify the navigation schema

connecting the different functionalities.

3.5 Visual Design

The general graphical appearance and textual fonts

will be determined in this phase. We recommend

setting the visual design in accordance with the

Charter of communication and graphical design of

the company to maintain familiarities with

interfaces. Moreover, improvements in usability can

be made if necessary. One possibility is to stage the

main use cases, and discuss with the users on

proposed models. We therefore recommend a

prototyping approach which allows the improvement

of the visual design.

The last two steps of our methodology, design of the

skeleton of the platform and visual design, are

highly sensory and will impact the user experience.

The designer will have to be particularly careful

when developing the platform in terms of

ergonomics; He will also be able to develop

motivators, all in accordance with user’s

expectations. This may require recycling regularly

through these steps.

4 IMPLEMENTATION

SCP offers an application context for the

implementation and evaluation of our methodology.

It is specialized in services related to the treatment

and distribution of water for companies, farmers and

communities. It employs a significant number of

persons, operators responsible for the maintenance

of hydraulic structures also called infrastructures

(e.g. canals, pumping stations, water purification

stations). Operators work in a territory which is

divided into ten geographical areas called operation

centres. SCP has developed a KMS, ALEX which

has the same features as a knowledge book. It

contains information on the activities of agents of

the SCP and makes this information accessible

through experience sheets in html format. Faced

with the problem of limited use of ALEX by the

operators, we proposed to SCP to redesign their

system using our methodology. The re-design was

done with a working group of twelve people that are

representative in terms of function and competence

of all future users of the system. It lasted five

months and six meetings allowed to monitor the

project.

4.1 Deployment of the Methodology

4.1.1 Needs Analysis

The study of the initial system showed that the

information filled in on business procedures was

generally of good quality, which is fine since we

haven’t had to rework on the formalization of the

knowledge itself. By cons, this phase allowed us to

detect that the original system did not meet the basic

employees’ needs, what explained the limited use of

the system. Interactions with the panel during this

phase allowed the users to express their wish to have

an accessible platform both in the office and outside,

that is easy to learn, but effective, which reduces the

time for entering information, which facilitates data

search and allows exchanges between employees. In

addition, our intervention focused on the type of the

KMS, we went about designing a website for ESN.

4.1.2 Specification of the ESN

During focus groups, the following roles have been

Re-DesigningKnowledgeManagementSystems-TowardsUser-CentredDesignMethodsIntegratingInformation

Architecture

301

defined: the administrator, the validator, the

contributor and the commentator. Employees,

depending on the role they have in the system, are

more or less involved in the animation of the

platform and content validation. These roles helped

develop access features for system security levels

and promote empowerment of actors. We proposed

to collaborators to integrate in the ESN, features

such as the submission and publication of pre-

formatted forms, submitting comments on the

experience sheets, news from the operation centres,

photo albums, discussion forums, features to

moderate submissions based on roles. After

discussion, it was decided that the submission is

made by the contributor under moderation of the

validator or the administrator. It is done using forms

with large areas of open writing because the activity

is too complex to be defined by a structure;

employees without any role distinction communicate

by commentaries left on the sheets. These comments

serve to convey the appreciation of the reader

regarding the record, as its content is a good idea to

generalize or if there is a need for additional

information; research content is natural language or

keywords; photos of the album will be indexed

according to the operating structures and equipment

in order to facilitate research centres.

4.1.3 Design of the Information Structure

In this stage, we identified informational patterns

related to business concepts: operations done by the

collaborators on infrastructures are described in

experience sheets, descriptions of equipment,

operating instructions, interventions of process type,

alarms, etc. This has resulted in the definition of

eleven types of sheets: presentation, equipment, set

operating instructions, hydraulic diagram,

spreadsheet, process, operation, alarm, contract /

contact and detail. Each item is described by a

presentation sheet that can be associated with one or

more sheets of the other types.

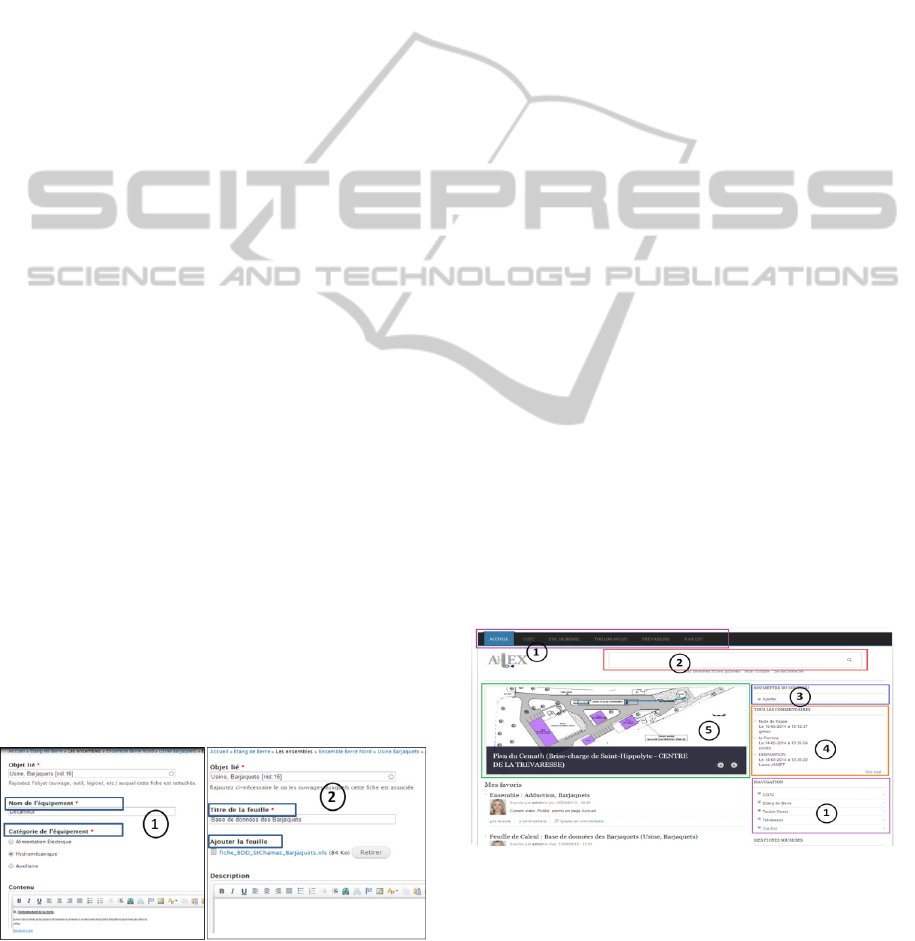

Figure 1: View of two types of sheets. Form 1 is an

equipment sheet and the 2

nd

, a worksheet; all the fields

differ depending on the type.

Each sheet is presented as a form formatted

according to its type-specific metadata (type of

equipment for equipment sheets or instruction name

for operating instruction sheets), by cons, the content

of fields is open written.

4.1.4 Skeleton Design

This phase was animated by discussions on the basis

of a proposal of a skeleton made with a content

management system (CMS) named Drupal. The use

of a CMS allowed us to accelerate the development

and modifications of the prototype according to the

users’ feedback. In the light of the opinions that

have been collected, we made the proposal to

reorganize the new system in different functional

areas gathering the main features of ALEX that are

information, submission, navigation and

communication. The content is classified in

accordance with the operational centres of the users

and the types of sheets.

4.1.5 Visual Design

On the visual aspects of the site, we started with a

proposal of "theming" and, according to different

users’ feedback, we adapted the different choices. In

this phase, we had to get into the skin of each user

type and depending on the use case, to make choices

that facilitate the use of the tool. As examples, we

can cite the search area that has been enlarged and

positioned prominently at the top right corner, the

default font for the fill of sheets that has been

standardized to Arial, size 12, or the area for data

entry that has been enlarged.

4.1.6 Alex+

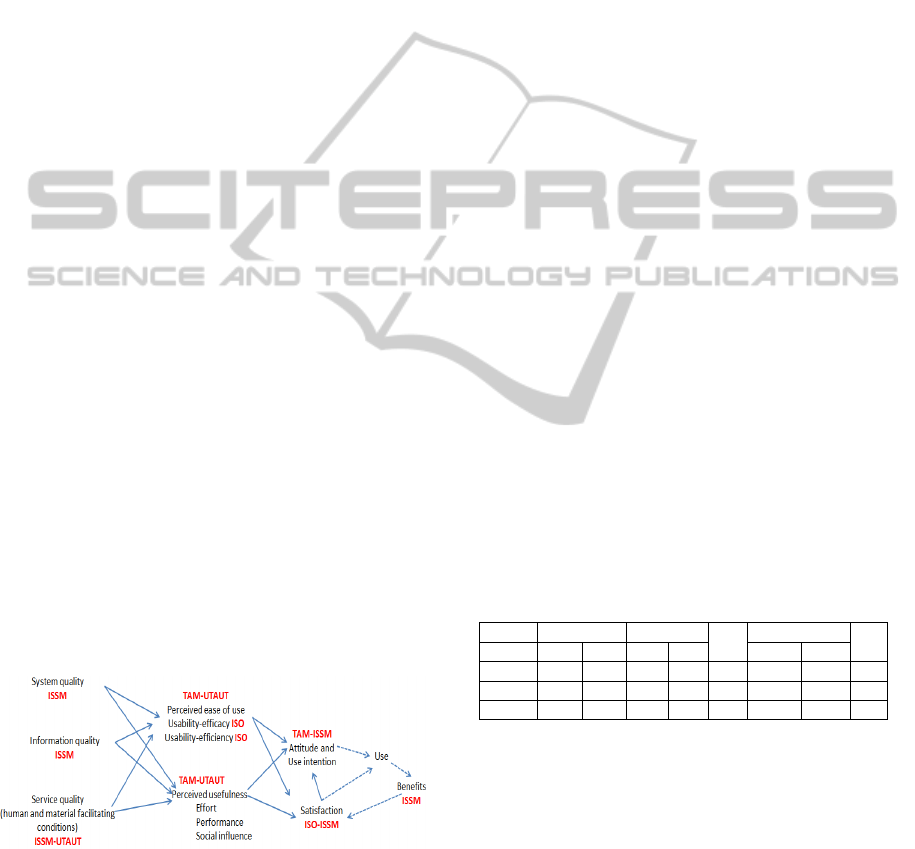

Figure 2: View of the ALEX+ front page. Zones 1 present

the different types of navigation by tabs at the top or a

menu block on the right. Zone 2 shows the search form

and in zone 3 we positioned the block content submission.

The regions 4 and 5 show a slideshow of the comments on

sheets and the photos posted.

This methodology has enabled the delivery of a new

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

302

version of ALEX named ALEX +. Features have

been proposed in order to improve the user

experience in terms of complexity and duration,

during the activity of corporate knowledge. An

assessment has been made and is detailed in the next

section.

4.2 Evaluation

The ergonomic cognitive psychology assumes three

dimensions for systems evaluation: systems that are

usefulness (does the system meet the user’s needs?),

usability (how does he respond to the user’s needs?)

and acceptability (is it acceptable?). To validate our

approach, we defined criteria to measure the level of

utility, usability and acceptability of our prototype.

4.2.1 Evaluation Criteria

We used the quality of the system and information,

utility, usability and satisfaction. They were chosen

because are they are emblematic of the success of

the technology acceptance according to different

models. TAM (Davis, 1993) and the UTAUT

models (Venkatesh et al., 2003), consider the

perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use as

basics of attitudes and behaviours of users. The

ISSM model (Delone, 2003) considers the quality of

the functionalities, the information and services

provided by the system as determinant for intention

and effective use of the system. ISO 9241-11 model

assumes that usability (effectiveness, efficiency and

satisfaction) is a necessary condition for use

(Février, 2011). According to these reference

models, we constituted a summary model that

describes how the process of acceptance should

occur. The following figure presents this summary

model with the evaluation criteria we used to form

the questionnaire and evaluate our methodology.

Figure 3: Summary model for acceptance of systems.

4.2.2 Data Gathering

The evaluation was conducted on the entire user

panel, namely the 12 members of the working group.

This was about completing a questionnaire

organized into nine sections describing the nine

factors listed in the previous model: System Quality

(QS), Quality of information (QI), perceived Ease of

use (FUP), Attitude toward the use of the application

(ATT), Intention to use (IC), Service Quality (How

is the system proposed by the SCP?), professional

perceived Usefulness related to the use of the

application (UPR), Personal perceived Usefulness

related to the use of the application (UPE) and

Satisfaction (SA). Each section contains a series of 4

to 6 questions (Touré, 2013).

4.2.3 Results

The results (cf. Table 1) show a majority of positive

answers to the questions concerning the quality of

the system and information, the perceived

usefulness, acceptability and satisfaction. Users are

generally satisfied and feel comfortable with the idea

of using a social network as a platform for

collaboration and sharing. This helps us assume that

we will notice an increase of the system use when it

will be put in production in the company. One can

therefore note that a proportion of users do not

perceive the professional and personal usefulness of

the system. It can be explained by the fact that they

are experts in their field and that the use of the tool

does not necessarily provide them with an

improvement of their skills. Users with this profile

will tend to submit naturally but in long term they

can find less or no motivation to use the system.

Initial acceptance of KMS does not guarantee

continuous and sustainable use (He & Wei, 2009).

This issue will be part of the study in future works.

Table 1: Results. PA: Positive answers; NA: Negative

answers; A: Abstentions.

QS and QI UP

FUP

ATT and IC

SA

QS QI UPR UPE ATT IC

PA(%) 96,3 83,3 64,4 66,7 88,9 85,2 71,1 86,1

N

A(%) 0 2,8 26,7 22,2 0 0 17,8 0

A(%) 3,7 13,9 8,9 11,1 11,1 14,8 11,1 13,9

5 CONCLUSION

Conventional methods of KM are mainly based on

the content and the formalization of knowledge.

Considering these limitations, we proposed a user-

centred approach to redesign KMS. Our

methodology combines HCI methods and IA.

Indeed, KM engineering methods are used to

identify and formalize corporate knowledge. They

are limited because they generally pay less attention

Re-DesigningKnowledgeManagementSystems-TowardsUser-CentredDesignMethodsIntegratingInformation

Architecture

303

to users’ point of view regarding the exploitation of

the knowledge produced. HMI methods are mainly

used to ensure that systems are useful, usable and

acceptable. The information architecture is used to

ensure that knowledge presented in KMS follows

structures that make the most sense for users and

their organizational context.

We implemented our approach in SCP and as a

result we obtained a prototype, ALEX +. ALEX +

was evaluated by a panel of users. It shows that

collaborators are generally satisfied with the

proposals that were made in the final system and

will tend more to use it. We can however identify a

couple of limitations in our approach. Firstly, the

limited number of participants in the workgroup

allows us to only have the viewpoints of a small part

of the actual user population; an assessment of a

larger amount of people in SCP and also in other

companies would help us have a better insight of the

impact of our methodology on the KMS use in the

company. Secondly, an ideal experimental approach

would be to do a comparative evaluation of our

methodology with others proposed by literature in

the domain of design of corporate KMS. These

points are planned for future work.

More generally, with our approach, we can just have

an overview of the users’ intentions but not of the

effective use. Our method is not robust enough to

ensure effective use; it focuses on initial acceptance

of the system but not on his continuous use. A KMS

is really useful if users effectively consult or add

new content, discuss or comment updates, which

happens when they master the system. This form of

capitalization, which we call sustainable, requires

implementation of other features in the system. This

stage corresponds to the sensory design stage which

we did not particularly emphasize in our approach.

We believe that metacognitive assistance features

like indicators of awareness may be useful (Marty &

Carron, 2011). Indeed, by proposing activity

indicators, we can promote a reflexive dynamic of

learning by user self-regulation processes (George,

Michel, & Ollagnier-Beldame, 2013). For example,

users by visualizing the impact of their contribution

on other actors in the company may be more

motivated to use the system. Conversely, by

identifying the comments that were made on

experience sheets related to their professional field,

they may become aware of new procedures or

changes in business practices and thus increase the

credit given to the developed tool. As such,

comments could be seen as a recommendation to

consult. We plan to implement these new features by

analysing traces of activity (Karray, Chebel-Morello,

& Zerhouni, 2014). These traces provide much more

diagnostic of use by sector and functionality. Our

future work will therefore seek to identify, still with

an incremental approach, which indicators and

interaction modalities may be most suitable. Phases

4 and 5 of our method are mainly concerned; the

design that affects the sensory and user experiences.

REFERENCES

Aries, S. (2014). Présentation de la méthode MASK.

Retrieved from http://aries.serge.free.fr/presentation/

MASKmet.pdf

Boucher, A. (2007). Ergonomie Web - Pour des sites web

efficaces.

Davis, F. D. (1993). User acceptance of information

technology : system characteristics, user perceptions

and behavioral impacts.

Delone, W. H. (2003). The DeLone and McLean model of

information systems success: a ten-year update.

Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4),

9–30.

Ermine, J. L. (2008). Management et ingénierie des

connaissances - Modèles et méthodes.

Février, F. (2011). Vers un modèle intégrateur

“Expérience-Acceptation” : Rôle des affects et de

caractéristiques personnelles et contextuelles dans la

détermination des intentions d’usage d'un

environnement numérique de travail.

Garrett, J. J. (2011). The elements of user experience -

Centered Design for the Web and Beyond.

George, S., Michel, C., & Ollagnier-Beldame, M. (2013).

Usages réflexifs des traces dans les environnements

informatiques pour l’apprentissage humain.

Intellectica, 1(59), 205–241. Retrieved from http://

hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00905173

He, W., & Wei, K.-K. (2009). What drives continued

knowledge sharing? An investigation of knowledge-

contribution and -seeking beliefs. Decision Support

Systems, 46(4), 826–838. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2008.

11.007

Karray, M.-H., Chebel-Morello, B., & Zerhouni, N.

(2014). PETRA: Process Evolution using a TRAce-

based system on a maintenance platform. Knowledge-

Based Systems. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2014.03.010

Marty, J.-C., & Carron, T. (2011). Observation of

Collaborative Activities in a Game-Based Learning

Platform. IEEE Transactions on Learning

Technologies, 4(1), 98–110. doi:10.1109/TLT.2011.1

Mathis, L. (2011). Designed for use, create usable

interfaces for applications and the web. Jill Steinberg.

Nielsen, J. (1993). Usability Engineering.

Prax, J. Y. (2003). Le Manuel du Knowledge Management

- Une approche de 2ème génération.

Resmini, A., & Rosati, L. (2011). Pervasive Information

Architecture - Designing Cross-Channel User

Experiences.

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

304

Stocker, A., & Müller, J. (2013). Exploring Factual and

Perceived Use and Benefits of a Web 2 . 0-based

Knowledge Management Application : The Siemens

Case References +.

Touré, C. (2013). Mise en place d’un dispositif de gestion

des connaissances pour le soutien à l'activité

industrielle (Master recherche). INSA Lyon.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Hall, M., Davis, G. B.,

Davis, F. D., & Walton, S. M. (2003). User acceptance

of information technology : Toward a unified view,

27(3), 425–478.

Zammit, R., & Woodman, M. (2013). Social Networks for

Knowledge Management. In The Third International

Conference on Social Eco-Informatics.

Re-DesigningKnowledgeManagementSystems-TowardsUser-CentredDesignMethodsIntegratingInformation

Architecture

305