AM2O

An Efficient Approach for Managing Training in Enterprise

Fod´e Tour´e

1

, Esma A¨ımeur

1

and Kimiz Dalkir

2

1

Department of Computer Science and Operations Research, Universit´e de Montr´eal, Montreal, Canada

2

School of Information Studies, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

Keywords:

Training Evaluation, Organizational Learning, Knowledge Management, Business Analysis, Return on

Equity, Optimization.

Abstract:

The learning function has grown and matured considerably in recent years, and evolved into a strategic support

function. Companies continue to invest in organizational learning and development, but rarely possess data to

assess the results of this investment. Most companies use the Kirkpatrick/Phillips model to evaluate enterprise

training. However, it emerges from the literature that enterprises have difficulties in using this model.

In this paper, we propose an approach based on analysing and modelling the training needs to ensure the

alignment between training activities and enterprise business objectives. It allows training project monitoring

as well as the calculation of tangible and intangible benefits of training (without added cost). Furthermore, it

enables the production of a classification of training projects according to criteria relevant to the enterprise.

Our approach can be used to optimize the training yield by a series of simulations based on machine learning

algorithms.

1 INTRODUCTION

The training evaluation aims at verifying if the com-

mitted efforts are translated by the outcomes which

matched the aimed objectives. However, when it is

question of making the link between learning pro-

grams and business results, organizational learning

functions have a track record of limited success.

A 2009 ASTD study revealed that the five-level

Kirkpatrick/Phillips model of learning evaluation is

the most commonly used model in practice. How-

ever, few organizations feel they have mastered the

learning evaluation, and many admit to facing ongo-

ing challenges (ASTD, 2009). The barriers that pre-

vent companies from using all the evaluation levels

are:

◦ Difficulty in isolating learning as a factor that

has an impact on corporate results.

◦ Lack of a useful evaluation system within the

Learning Management System (LMS).

◦ Lack of standardized data to properly compare

across training functions.

This paper presents a method of training project man-

agement (AM2O method): going from design to op-

timization via the evaluation of the financial and non-

financial yield. It also introduces our Enterprise

Training Program Management System - ETREOSys.

In section 2, we present our approach (AM2O

method). Section 3 provides a brief presentation of

the Kirkpatrick/Phillips model for the evaluation of

training programs in organizations. In section 4, we

discuss our results and section 5 is reserved for the

conclusions.

2 AM2O: AN APPROACH FOR

ENTERPRISE TRAINING

PROGRAM MANAGEMENT

We propose a four-step approach of enterprise train-

ing program management. This approach consists of

analysing training needs, process modelling, monitor-

ing the progress of a project while guaranteeing ex-

pected objectives, and optimizing the yield by a series

of simulations. These four steps are shown in Figure

1.

2.1 Stage 1 - Analysis

A corporate training program consists of a series of

405

Touré F., Aïmeur E. and Dalkir K..

AM2O - An Efficient Approach for Managing Training in Enterprise.

DOI: 10.5220/0005158204050412

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2014), pages 405-412

ISBN: 978-989-758-050-5

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

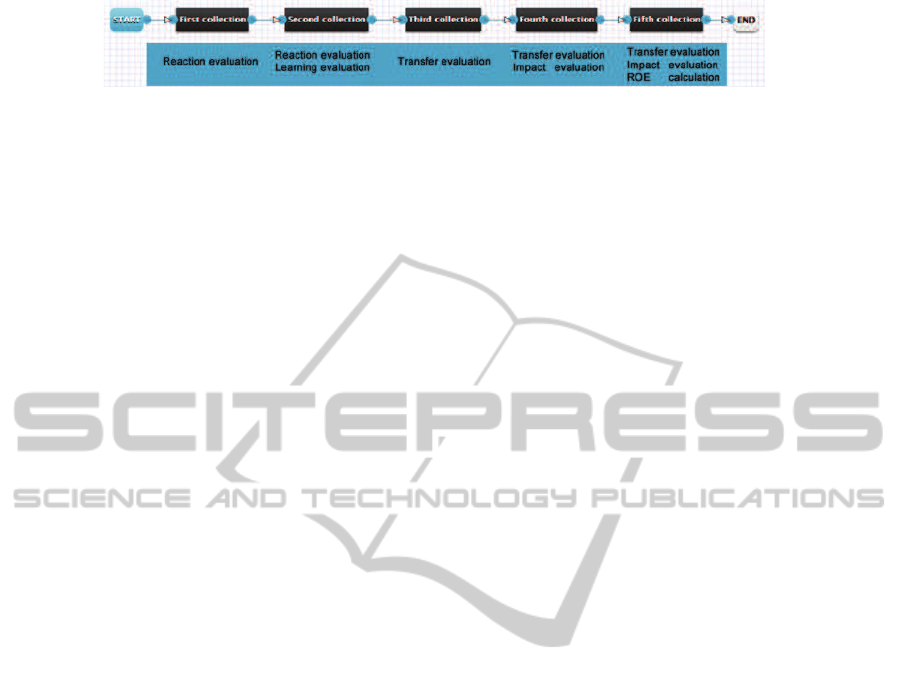

Figure 1: The stages of AM2O method.

specific actions intended to resolve an enterprise-

specific problem. According to Rivard and Lauzier

(2013), a need for training in an enterprise defines it-

self by the gap between what is (the current situation)

and what should be (the wished situation). It is thus

necessary to avoid launching too quickly a training

process before having well estimated the nature of the

problem raised in the enterprise.

The results of a study led by van Eerde et al.

(2008), with 96 companies, demonstrate that a rig-

orous analysis of needs leads to a greater perception

of the utility of training, what in return has a positive

effect on the efficiency of the organization. Hence,

the first stage of AM2O focuses on analysing the de-

mand for training and associating it with performance

elements of the enterprise. This stage requires a num-

ber of actions such as: consultations to explore de-

mand, definition of a changeplan, needs analysis, def-

initions of the objectives, and selection and definition

of performance indicators. Hence, we use a business

analysis process based on the International Institute

of Business Analysis (IIBA) guide.

IIBA maintains and publishes a repository con-

taining a description of the activities involved in busi-

ness analysis. The repository is published as a book

entitled ”A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of

Knowledge”(IIBA, 2009).

The development of systems and their compo-

nents is based on the description of needs. The de-

termination of the needs depends on the form and

the structure of the demand. The IIBA guide allows

us to answer several questions such as: Why would

you want to train employees? What needs have been

identified? What are the expectations? How will the

achievement (or not) of goals be assessed?

The analysis of the current situation produces a re-

port containing a structured presentation of harvested

information and details of the objectives, the means

and available resources, improvementproposals, risks

and potential impacts. Managers evaluate the orga-

nizational strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and

risks. A business process model is therefore based

on the identification of key elements in the conduct

of affairs such as endogenous and exogenous factors

directly acting on the fluctuations of the function-

ing mode of the enterprise. This reasoning solves

the problem of isolation of training impacts from the

overall performance of the organization. Indeed, we

can use the IIBA process to define the indicators re-

lated to the expected effects of the training and the

factors that may influence these effects. This means

that we also define the situations and indicators that

can produce the same effects as training.

In AM2O, the description of the intangible train-

ing yield is based on the values of qualitative indica-

tors. As these indicators are directly linked to specific

objectives, the successful achievement of these objec-

tives will be evaluated using the values of the corre-

sponding indicators. The same reasoning applies to

the calculation of the financial training yield.

This first stage of AM2O supplies the process

model, the information required to configure this

model, and the initial values of indicators. It ensures

the alignment of the training program with the growth

strategy of the enterprise. At this stage, we estimate

the Net Present Value (NPV) of the training invest-

ment before the beginning of the training program by

combining the NPV formula with the DuPont finan-

cial analysis method.

When a company or investor takes on a project or

investment, it is important to calculate an estimate of

how profitable the project or investment will be. NPV

is a formula used to determine the present value of an

investment from the discounted sum of all cash flows

received from the project. It compares the value of

a dollar today to the value of that same dollar in the

future, taking inflation and returns into account. The

formula for the discounted sum of all cash flows can

be rewritten as:

NPV =

T

∑

t=1

C

t

(1+ r)

t

−C

0

(1)

T is the number of years, C

t

is the cash flow at time t,

r is the discount rate (the rate of return that could be

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

406

earned on an investment in the financial markets with

similar risk - it is the interest rate) and C

0

is the initial

investment.

The cash flow is the movement of money into or

out of a business, project, or financial product. It is

usually measured during a specified, finite period of

time. Measurement of cash flow can be used to calcu-

late other parameters that give information on a com-

pany’s value and situation. For example: to improve

the yield of its shipping department, a warehouse (En-

terprise X) organizes training sessions for its employ-

ees on the use of scanners.

The analysis of the need for training shows that

Enterprise X just wants to increase its return to in-

vestors. To increase this return, it has to reduce the

cost of ordering errors and increase the number of or-

ders treated per hour in the whole department (thus

by all employees). The analysis of the current situa-

tion of the enterprise provides the simplified financial

balance sheet shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Example of simplified financial balance sheet.

Net profit Sales Assets Equity

$ 1 000 000 $ 10 000 000 $ 8 000 000 $ 4 000 000

Order errors represent an average cost of $200 000

to the company. The cost of the training is $500 000.

Enterprise X estimates that training will reduce the

cost of ordering errors by at least 50%. Also, increas-

ing the number of orders treated per hour will have a

positive impact on sales and net profit. This increase

also saves the salary of seasonal workers, the cost of

their recruitment and their training (e.g. $ 150 000).

Such information can be used to estimate the NPV of

the investment in training before the program begins.

In the case of Enterprise X, assuming that the

training generates a constant income, for a constant

risk of 10%, we have the following NPV:

NPV =

100000+ 150000

1.1

+

250000

1.1

2

+ . . .

+

250000

1.1

T

− 500000 (2)

According to the previous calculation, we note that

the value of NPV will be positive only from the third

year onwards.

Normally, several aspects of financial statements

are affected by training which makes it more difficult

to estimate the impact on profit. Consequently, con-

trary to the previous example which was simple, in

more complex cases, the calculation of the NPV of an

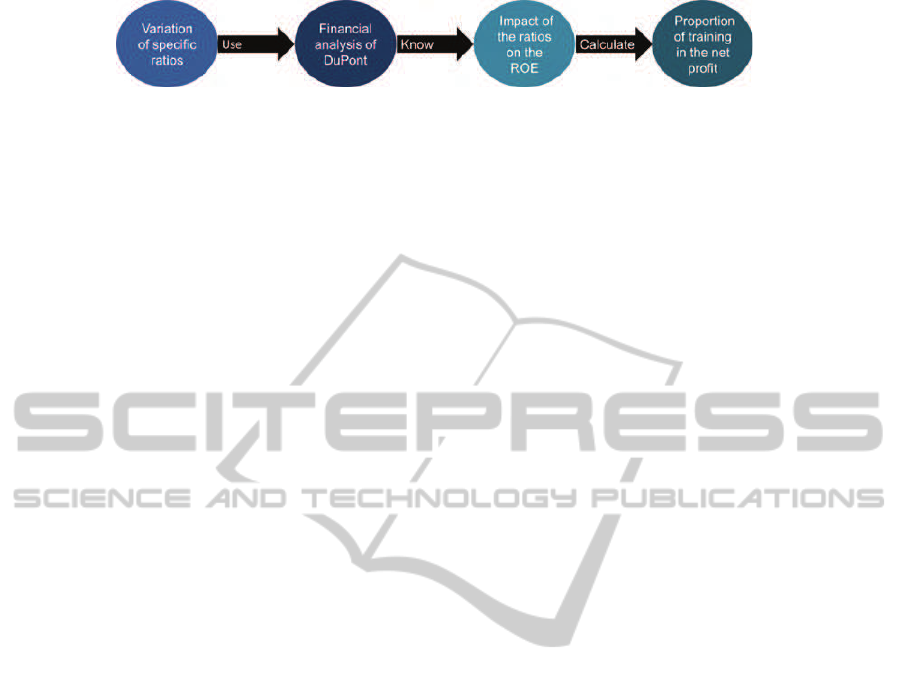

investment in training is done in five steps (Figure 2).

Indeed, the use of the IIBA guide produces a set

of indicators (ratios) for assessing the success of the

training. These ratios can be used in the decomposi-

tion (first and second level) of the DuPont model in

order to calculate the cash flows associated with the

investment in training.

According to Soliman (2008) , the DuPont com-

ponents represent an incremental and viable form of

information about the operating characteristics of a

firm. With this method, assets are measured at their

gross book value rather than at net book value in order

to produce a higher return on equity (ROE). It is a ra-

tio analysis system that quickly allows us to determine

if a company is using all the means at its disposal to

reach its financial goal. The DuPont analysis helps

locate the part of the business that is underperforming

(if ROE is unsatisfactory). This analysis tells us that

the ROE is affected by three sub-ratios:

◦ Operating efficiency, which is measured by profit

margin.

◦ Asset use efficiency, which is measured by total

asset turnover.

◦ Financial leverage, which is measured by the eq-

uity multiplier.

ROE = Profit Margin∗ Total Asset Turnover

∗ Equity Multiplier (3)

Profil Margin =

Profit

Sales

TotalAsset Turnover =

Sales

Assets

Equity Multiplier =

Assets

Equity

ROE =

Profit

Equity

For example, by using Table 1, we obtain the follow-

ing ROE:

ROE =

10

6

10

7

∗

10

7

8∗ 10

6

∗

8∗ 10

6

4∗ 10

6

= 0.25

The result of the calculation of the ROE means that

every dollar invested in the company by the share-

holders generates 25% (25cent) of profit.

A better analysis of the training project would be

to associate indicators, supplied by the first stage of

our approach, with certain ratios of the DuPont de-

composition. This will help to pinpoint the exact im-

pact of training on the return on equity (specifically on

net profit). A comparative analysis with the scenario

without investment in training allows us to isolate the

relevant cash-flow to be used in the NPV formula.

Using the same example of Enterprise X, the re-

duction of the cost of ordering errors and the increase

AM2O-AnEfficientApproachforManagingTraininginEnterprise

407

Figure 2: Procedure for estimating the profitability of a training investment.

of the number of orders treated per hour will have

an impact on the net margin ratio and the total asset

turnover ratio. Thus, from the decomposition of the

DuPont model, if improvements due to training in-

creased the return on equity of β (i.e. the net profit of

β), then we can use the NPV formula to determine the

future earnings of investment in training according to

the following equation:

NPV =

T

∑

t=1

β∗ netprofit

(1+ r)

t

−C

0

(4)

Depending on the value of NPV, and whether it is

above or below a threshold set by the company, the

decision will then be to either fund or not fund the

training project.

2.2 Stage 2 - Modelling

This stage allows us to model a business process us-

ing graphic objects developed by the Workflow Man-

agement Coalition language. In this modelling lan-

guage, we use two object types: nodes and flows.

The nodes are classified into two categories: task and

choice (condition). A task, graphically represented by

a rectangle, represents the work to be done to achieve

some objectives. A choice, graphically represented

by a circle, is used to build conditional structures. A

flow links two nodes in graph and is graphically rep-

resented by an arrow.

For training project management, there are at least

two process models: the process model related to

the training plan and the process model related to

the stages of data collection and training performance

evaluation.

The training plan is a graphical representation of

the syllabus (course outline). To illustrate this con-

cept, let us take the example of an enterprise, which

would like to improve the performance of its cus-

tomers’ service department. The enterprise would

like employees to make a complex analysis of con-

sumer behaviour and communicate results to man-

agers and strategic advisors. This means that employ-

ees must be trained on consumer behaviour. Figure 3

shows a process model of the planning of this train-

ing.

In AM2O, the actors of each activity and their

roles, the description of incoming and outgoing data,

the temporal aspect and the performance indicators

Figure 3: A possible process model for a training plan for

consumer behaviour.

related to training are also added to the graph. Sam-

ple indicators may include: average emotional state

of learner, average emotional state of trainees during

training sessions, and satisfaction of the organization

with the training program, Employees’ satisfaction

can be measured with such indicators as satisfaction

with respect to the content, perceived relevancy and

usefulness of training.

The planning of the data collection and training

evaluation consists of collecting information before,

during and after the training (see Figure 4). In A2MO,

we define the means of data collection, dates, the ob-

jectives, the actors and the corresponding indicators

for each stage. All information is kept in ETREOSys

to facilitate the management of the training program.

Consequently, besides the already mentioned indica-

tors, we define other indicators that allow us to esti-

mate the achievement of the training objectives in the

enterprise. These indicators relate to the employees’

lives in the enterprise before and after the training.

Some examples would be: increase innovation level

of an employee, increase general level of innovation

in the enterprise, improve product quality, work cli-

mate, the number of committee meetings, customers

loyalty, and profit by employee.

We can also isolate the indicators which can in-

fluence those previously discussed (with or without

training program). For example: rate of staff turnover,

rate of employee absenteeism, number of absences

per employee, cause of absences, cost of the rotation,

cost engendered by absenteeism, cost of absence per

employee, degree of job satisfaction, degree of per-

sonal initiative, staff productivity, level of collabora-

tion between employees within the enterprise, level of

collaboration per employee and so on.

In the case of the training modelled in Figure 3, we

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

408

Figure 4: A possible process model for training evaluation planning.

must take into account the influence of environmental

factors on consumer behaviour such as culture, refer-

ence groups, social class or family. Therefore, it is

necessary to define indicators in order to isolate the

influence of these external elements.

The evaluation process model (Figure 4) fixes pe-

riods of gathering information in order to proceed

with evaluations and simulations to predict result

trends. This information will allow us to make de-

cisions leading to the success of the training program.

The evaluation process model will allow us to react in

real time to avoid failure of training (non-realization

of the objectives). For this purpose, it is enough to

compare the initial values, the collected values and

the expectations of the enterprise.

The deployment of invalid processes can lead to

incoherent states and can even provoke very critical

breakdowns without the slightest possibility of recov-

ery. In other words, if a process is put in production

before being validated, it could fail during the exe-

cution stage and cause considerable loss to the en-

terprise. To check the syntactic validity, we analyse

the structure of the process model. For this, we use a

simplified and enhanced version of the Tour´e hybrid

algorithm (Tour´e et al., 2008). On the other hand, to

check the semantic validity, we need to analyse the

information treated by the tasks and the behaviour of

the latter (in the first stage of AM2O, see section 2.1,

caution must be taken in order to avoid semantic con-

flicts).

The first and second stages of AM2O are impor-

tant because they ensure a responsible management

of the training program and serve as the basis for the

success of the stages 3 and 4.

2.3 Stage 3: Monitoring

This stage of AM2O consists of controlling the

progress of the processes. A control system based

on relevant and precise indicators is needed in or-

der to have dashboards used to make good decisions

quickly. The training dashboard has to cover two di-

mensions: efficiency and efficacy. The training pro-

cess is said to be efficient if it gives maximum results

while consuming minimum resources and said to be

effective if it provides the expected results.

This stage allows us to calculate the tangible and

intangible training benefits (without additional costs)

by using the values of the indicators. To estimate the

impact of training on cost, we compare indicator val-

ues before training and after training. The calculation

of the return on training investment is explained by

the process shown in the Figure 5.

When we decide to calculate the financial yield

on training investment, we determine the gap between

the previous and current values of the quantitative in-

dicators (ratios). Furthermore, the intangible bene-

fits can be converted into tangible factors with a good

understanding of profit. For example: the improve-

ment of employee morale (intangible) can be con-

verted as follows: improving employee morale can

increase employee retention, which can be assessed as

the cost saving related to hiring and training new em-

ployees. Based on staff turnover last year, the human

resources department can provide concrete numbers

like ”Reducing employee turnover by 5% will save $

5,000 in recruitment costs.”

By using the DuPont model (see equation 3), we

estimate the impact of the variation in ROE indicators

on the ROE. This process allows us to calculate the

impact of training on the overall profitability of the

company.

2.4 Stage 4: Optimization

In this stage, we use machine learning algorithms (ex-

ample, logistic regression, neural networks or support

vector machines) to classify training activities accord-

ing to defined criteria (example, financial yield) and to

conduct simulations to increase the efficiency and ef-

fectiveness of training activities. To do that, we carry

out a pre-treatment on the indicator values to have a

data set for a learning algorithm (supervised, unsuper-

vised or semi-supervised). When the training evalua-

tion process is completed, the enterprise training pro-

grams will be classified into two categories: profitable

and unprofitable. Hence, we will have a dataset D

n

that can be used in the training of a machine learning

algorithm.

D

n

= {Z

1

, Z

2

, . . . , Z

n

}

∀i ∈ {1, 2, . . . , n}, Z

i

= (x

(i)

, t

(i)

) with x

(i)

∈ R

d

and t

(i)

∈ {0, 1}

Each Z

i

is associated with a particular training pro-

gram in the enterprise. The x

(i)

values are the indica-

tors (see 2.1 and 2.2) related to the training. Hence,

AM2O-AnEfficientApproachforManagingTraininginEnterprise

409

Figure 5: How to calculate the return on training investment.

we can have indicators which take numerical values

(for example, number of committee meetings) and

others that take categorical values (for example, ordi-

nal and nominal values). The t

(i)

values represent the

training class (profitable or unprofitable), where prof-

itable corresponds to 1 and unprofitable corresponds

to 0. The number of completed training program is n

and the number of indicators is d.

In our approach, the purpose of the classifica-

tion is to be able to predict the achievement or non-

achievement of the training objectives by observing

only the indicators behaviour. Furthermore, we must

be able to determine the indicators which have more

weight in the attainment of training objectives. That’s

why we may use a parametric machine learning al-

gorithm like logistic regression, neural networks or

support vector machines.

The optimization consists of a simulation that

guides the training process towards the achievement

of its objectives. To do this we may use semi-

supervised learning. The goal of a semi-supervised

learning is to understand how combining labelled and

unlabelled data may change the learning behaviour,

and design algorithms can be developed that take ad-

vantage of such a combination. For this, we need to

render the values of the indicators that we want to pre-

dict as discrete variables. This is a binary classifica-

tion process (the value is good or bad) based on the

recommendations of a human expert. For example,

the indicator number of absences per employee is 1 if

its value is below the threshold set by a human expert

(or according to the functioning of the enterprise) and

0 otherwise.

To facilitate the understanding and the use of

AM2O, we developed an enterprise learning man-

agement system named Enterprise TRaining program

Evaluation and Optimization System ETREOSys.

3 RELATED WORK

Work on Kirkpatrick’s model began in 1959, with a

series of four articles on the evaluation of training

programs in the journal ”Training and Development”.

These four articles defined the four levels of eval-

uation that would later have a significant influence

on corporate practices (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick,

2006).

Level 1 - Students Reaction

How did the trainees react after the training? Did they

appreciate it? Were they satisfied? What did they

think and feel about the training?

Level 2 - Learning

What did they learn after the training? What knowl-

edge, skills and/or attitudes were acquired? Were ed-

ucational objectives been achieved? Was there a re-

sulting increase in knowledge or capability?

Level 3 - Behavior

Do trainees use what they learned in training at their

workplace? What new professional behaviours have

been adopted?

Level 4 - Results

What is the impact of the training on the results of

the company? For example: decrease in absenteeism

or occupational accidents, growth of asset turnover,

of productivity, or customer satisfaction, etc. The ef-

fects on the business or environment resulting from

improved trainee performance.

Although the Kirkpatricks’ four-levelmodel is widely

recognized and accepted, and although a significant

number of evaluation methods are based on it, many

researchers have argued that this method does not

provide adequate data required by today’s managers.

According to Phillips, training yield calculation

proceeds by stages, which supplies a detailed plan

for the collection and analysis of the data, which

includes the calculation of Return On Investment

(ROI). So Phillips suggested the inclusion of a fifth

level in 1996 (Phillips and Phillips, 2003).

Level 5 - Return on Investment

Comparison between the profit obtained from the

training and the training costs. Profits and/or savings

realized are they superior to the total cost of the

training (direct and indirect costs)? Did the training

generate a return on investment?

The ROI calculation process begins with planning for

training evaluation: where objectives are defined and

decisions are taken on the way the data will be col-

lected, treated, and analysed. Data collection is car-

ried out according to the training evaluation levels 1

to 4 of Kirkpatrick’s model.

However, in the literature, several criticisms have

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

410

been raised with regard to the Kirkpatrick/Phillips

model. According to Mumma and Thatcher (2009)

, the entire notion of the Kirkpatrick/Phillips model

may not truly measure the impact of the learning func-

tion on the enterprise, even under the most optimistic

scenarios. It measures only the possible impact of iso-

lated training events. Nagle (2002) reports a series

of criticisms of the ROI calculation process such as:

difficulty to have a valid measure, expensive process,

complex process, process that can take up to one year,

and presence of other factors that influence the perfor-

mance of the organization. Concerning the method-

ological problems, McCain (2004) established a list

of biases that could have an impact on the observed

results which a training professional does not always

think of. These include bias of a sample (selection of

a non-representative sample or too small a sample),

bias in the interviews, and bias in the presentation of

questions.

4 DISCUSSION

Given that our objective is to respond to business

needs concerning the management of training pro-

grams, this demonstration will be supported through

comparison criteria based on the results of surveys

conducted in the workplace by ASTD ic4p (ASTD,

2009) and others such as Formaeva (Formaeva,

2011). The criteria and their definitions are:

Efficiency. It is the criterion associated with an

evaluation model, which refers to maximizing results

while consuming a minimum of resources. An

efficient model does not create any additional costs

when calculating the training yield.

Usability. This criterion refers to the ease and the

simplicity of using a model to evaluate a training

program. The complexity involved in using a model

is a barrier which can prevent companies from

effectively evaluating their training program.

Implementation. Surveys have revealed that one of

the barriers which can prevent companies from fully

exploiting the existing models is the lack of IT tools.

This assumes that a model which is implemented

through an IT tool is more likely to be used by the

companies and training professionals.

Diagnosis. This criterion refers to the ability of a

model to identify the causes of the success or the

failure of a training program. A model able to supply

a diagnosis of a training program is a powerful

decision-making tool.

Widespread. This criterion captures the fact that

many companies use a model or that it is better

known than another model.

The model of Kirkpatrick allows to evaluate the train-

ing at various levels of learnings integration. It also

enjoys great recognition with the professionals of the

training. Its main limitation is the fact that it does

not explain in what a training is effective or ineffec-

tive (Holton, 1996; Saks and Haccoun, 2013). From a

diagnostic standpoint, this evaluation model does not

either indicate how to improve the training strategy

used.

Besides, Saks and Burke (2012) were interested

in the evaluation process by using the model with

four levels of Kirkpatrick. Their research was con-

ducted among 150 members of a Canadian associa-

tion of training who work for organizations with be-

tween 500 and 1, 000 employees. The authors raise

the following paradox (which is consistent with pre-

vious research): enterprises measure more the reac-

tions and the learnings, while only the behaviors and

the results are positively related to a higher level of

learnings transfer.

The Kirkpatrick/Phillips model does not inte-

grate the business analysis component. This analy-

sis should be done before employees begin training.

This fact is one major handicap to the success of the

training evaluation and explains why enterprises can-

not correctly and easily apply the Kirkpatrick/Phillips

model (especially level 3). Indeed, the indicators used

at level 4 of the Kirkpatrick model should be known

during the management process, even before the first

level of this model (Kirkpatrick/Phillips). This obser-

vation confirms the fact that the Kirkpatrick/Phillips

model does not supply the required information for

an analysis and adequate evaluation of the training.

Given that level 5 (added by Phillips) uses the data

provided by level 4 of Kirkpatrick, it also inherits the

gaps and weaknesses of the latter. Indeed, Kirkpatrick

recommends using their model in hierarchical order

(1, 2, 3, and 4). Consequently, given that the supplied

data are not sufficient and (given the delay in cov-

erage of the training management), the ROI process

calculation (level 5 of Phillips) becomes complicated

and useless due to lack of adequate data. Table 2,

below, summarizes the comparison between our ap-

proach and the Kirkpatrick/Phillip model.

Finally, according to Rivard and Lauzier (2013),

it’s better to adopt a methodology which let you

quickly fix a training strategy which does not give the

wished results than ending up in a situation where we

demonstrate that a training given to all employees is

not ultimately effective. This point of view demon-

strates the usefulness of AM2O and ETREOSys.

AM2O-AnEfficientApproachforManagingTraininginEnterprise

411

Table 2: Comparison table of our model to the Kirkpatrick

/ Phillips model.

Efficiency

Usability

Implementation

Diagnosis

Widespread

Kirkpatrick/Phillips No No No No Yes

Our approach Yes Yes Yes Yes No

5 CONCLUSION

The advantages obtained through our approach can

be seen from two angles. In the domain of business

process management, we add a new category of busi-

ness process and we extend the business process man-

agement systems by adding training management and

evaluation functions (through ETREOSys).

Concerning the evaluation of enterprise training,

we propose a more comprehensive approach for train-

ing project management, one that facilitates decision-

making and the calculation of the tangible and intan-

gible profits.

Relating to the problems raised in the literature,

we reduce the biases and additional costs associ-

ated with training yield calculation. Indeed, we tie

the training objectives and strategies to the perfor-

mance wish list of the enterprise in the training de-

sign. Hence, from the beginning, the enterprise would

be able to connect the expected outcomes with certain

indicators used in the current functioning of the en-

terprise. When financial yield evaluation is required,

our approach enables companies, to supply data from

the quantitative indicators which will show the evolu-

tion of productivity and translate them into economic

value without incurring additional costs. They could

also use the qualitative indicators to demonstrate the

social yield of training.

Finally, our approach ensures that training activ-

ities are aligned with business needs and allows the

ROI (or ROE) calculation to be made without addi-

tional investment.

REFERENCES

ASTD (2009). The Value of Evaluation: Making Training

Evaluations More Effective. ASTD Press.

Formaeva (2011). Synth`ese d’´etude: Les pratiques

d’´evaluation des formations des entreprises franc¸aises

en 2011. Technical report, Formaeva. Formaeva:

´

Evaluer pour Mieux Former.

Holton, E. F. (1996). The flawed four-level evaluation

model. Human Resource Development Quarterly,

7(1):5–21.

IIBA (2009). A guide to the Business Analysis Body of

Knowledge (BABOK guide), version 2.0. International

Institute of Business Analysis.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. and Kirkpatrick, J. D. (2006). Evalu-

ating Training Programs: The Four Levels (3rd Edi-

tion). Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 3rd edition.

McCain, D. (2004). Evaluation basics. ASTD, 1st edition.

Mumma, S. and Thatcher, C. (2009). The learning profit

chain ”connecting learning investments to financial

performance”. Corporate University Xchange.

Nagle, B. (2002). Roi gives a way to roe. Candian HR

Reporter,, 15(13):7.

Phillips, J. J. and Phillips, P. P. (2003). Using action plans to

measure roi. Performance Improvement, 42(1):24–33.

Rivard, P. and Lauzier, M. (2013). La gestion de la for-

mation et du d´eveloppement des ressources humaines:

Pour pr´eserver et accroˆıtre le capital comp´etence de

l’organisation. 2e edition.

Saks, A. M. and Burke, L. A. (2012). An investigation into

the relationship between training evaluation and the

transfer of training. International Journal of Training

and Development, 16(2):118–127.

Saks, A. M. and Haccoun, R. R. (2013). Managing Per-

formance through Training and Development. Nelson

Education, 6th edition.

Soliman, M. (2008). The use of dupont analysis by market

participants. The Accounting Review, 83(3):823–853.

Tour´e, F., Ba¨ına, K., and Benali, K. (2008). An efficient

algorithm for workflow graph structural verification.

In Meersman, R. and Tari, Z., editors, OTM Confer-

ences (1), volume 5331 of Lecture Notes in Computer

Science, pages 392–408. Springer.

van Eerde, W., Simon Tang, K., and Talbot, G. (2008). The

mediating role of training utility in the relationship be-

tween training needs assessment and organizational

effectiveness. The International Journal of Human

Resource Management, 19(1):63–73.

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

412