Opinion-Ontologies

Short and Sharp

Iaakov Exman

Software Engineering Dept., The Jerusalem College of Engineering – JCE Azrieli, Jerusalem, Israel

Keywords: Opinion-Ontologies, Subjective, Sharp, Tweetable, Recommendation.

Abstract: Opinion-Ontology is a short and sharp tweetable recommendation conceptualization which can be actually

sent in a message. But, one should ask in which sense is this a true ontology? On the one hand, it does not

represent the common vocabulary or the shared meanings of a domain, as it is subjective. On the other hand,

it does contain a semantic structure, which in spite of being subjective enables making inferences and taking

rational decisions in practical situations. These are demonstrated by case studies with several examples of

booking a table in a restaurant or a room in a hotel in previously unvisited places. The proposed

characteristics of opinion-ontologies – efficient information transmission and integration with similar

opinion-ontologies without expanding their sizes – can be and we actually intend to implement in a software

system, to enable testing in practice, the whole approach.

1 INTRODUCTION

In view of the rapid changes in the personal way of

decision making, caused by:

Web usage – for booking hotels and flights,

scheduling meetings in restaurants, etc. in

previously unvisited places;

Fast messages – in SMS format, in tweets,

smartphone applications or location-based

social networks;

the booking individual is increasingly relying upon

personal opinions and recommendations. Therefore

new methods to evaluate reliability of opinions and

recommendations are needed.

This work proposes a way to increase reliability

while keeping the overall semantic information – the

basis of judgment evaluation – contained in a limited

size.

Opinion-ontologies are short information pieces

that can be transmitted by fast messages and

integrated with previous messages, without

increasing overall size. This is possible, and

distinguishes them from free-form messages, due to

their structured semantic content.

1.1 Related Work

Opinion and ontologies have been dealt

fromdifferent perspectives. Chang et al. (Chang,

2005) deal with reputation ontologies. They refer

among other things to “Trustworthiness of Opinion

Ontology”. Li and Du (Li, 2011) investigate

ontology-based opinion leader identification for

marketing in online social blogs.

Cambria et al. (Cambria, 2010) describe a public

semantic resource for Opinion Mining, called

SenticNet. Sentic Computing enables analysis of

even very short documents – say one sentence.

Opinion-ontologies are a recent example of short

flexible ontologies for specific purposes. Previous

examples involved micro-ontologies – discussed in

(Biagioli, 1997), nano-ontologies – discussed in the

context of misbehaviour (Exman, 2013), – and

pluggable ontologies – discussed in the context of

non-concepts (Exman, 2012).

The concept of tweetable events and/or abstracts

appears in several contexts in the literature. For

instance, Kiciman (Kiciman, 2012) refers to events

that are interesting and tweetable. People have

thought about tweetable abstracts of scientific papers

as a means to force information compaction.

In a more general vein, there are works dealing

with the interplay of semantics and communication,

in particular for touristic services. See e.g. the

bibliography at the STI web site (STI, 2014).

Akbar et al. (Akbar, 2014) deal with semantic-

aware rules for online communication, among others

with social networks such as Twitter. Toma et al.

(Toma, November 2013) aim at scalable multi-

454

Exman I..

Opinion-Ontologies - Short and Sharp.

DOI: 10.5220/0005166104540458

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development (KEOD-2014), pages 454-458

ISBN: 978-989-758-049-9

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

channel communication by means of semantic

technologies.

Toma et al. (Toma, 2014) refer to touristic

services with semantic annotations, using relevant

concepts mapped to types in schema.org

(schema.org, 2014). Toma et al. (Toma, June 2013)

specifically refer to the booking problem in the

tourism domain.

1.2 Paper Organization

The remaining of the paper is organized as follows.

Opinion-ontologies are first given a motivation in

section 2; syntactic, semantic and operational

properties of opinion-ontologies are described in

section 3; merging and inference operations on

opinion-ontologies are considered in section 4; case

studies are presented in section 5; the paper is

concluded with a discussion in section 6.

2 OPINION-ONTOLOGIES

MOTIVATED

The motivation behind opinion-ontologies is

twofold: to obtain condensed information and be

able to evaluate their reliability. Compact

information should be usable to make fast decisions.

2.1 Introductory Example:

A Restaurant Review

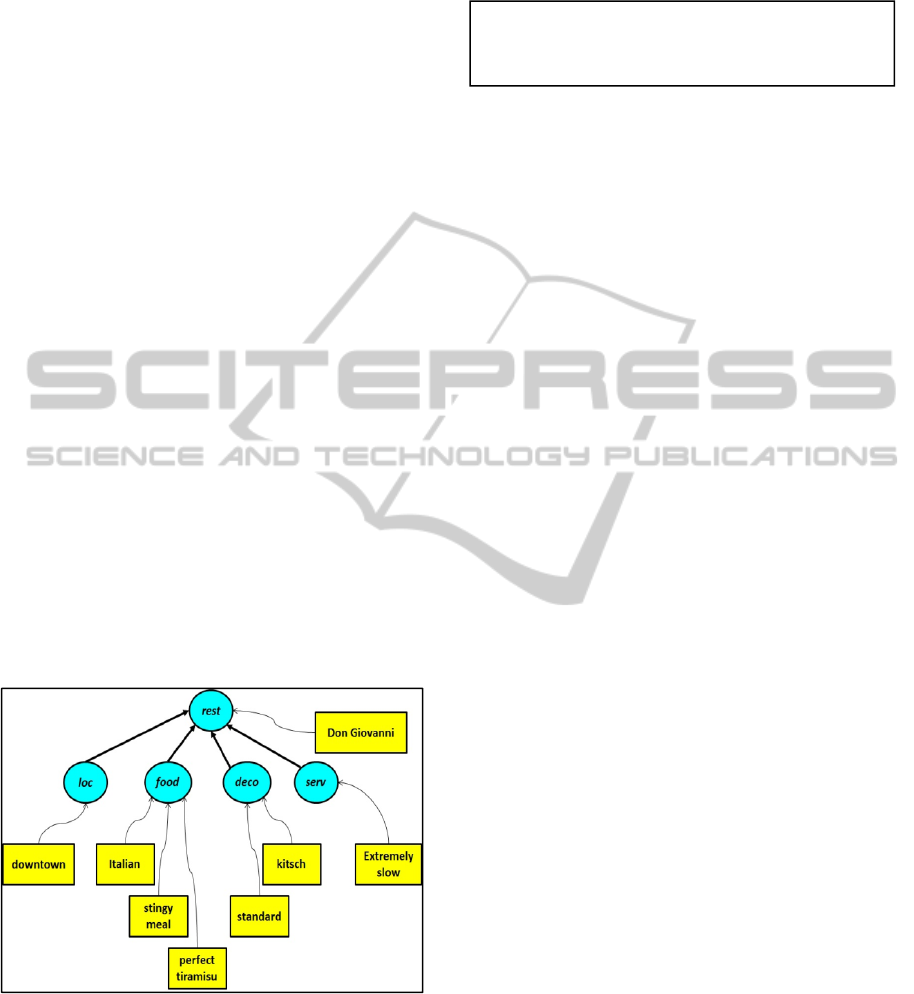

Figure 1: Schematic graphical representation of an opinion

ontology (opon) about a restaurant – Ellipses (in blue) are

classes, each of them linked by an association to the main

opon class rest (standing for restaurant). Rectangles (in

yellow) are property names, linked by a thin arrow to the

respective class.

Often there are in newspapers columns dedicated to

restaurant reviewing and ranking. Summarizing one

such specific column about an Italian style restaurant

could look as in the next opinion-ontology (from

now on abbreviated as opon):

This opinion-ontology conveys the opinion about

a restaurant named “Don Giovanni”. The restaurant

is located in downtown. It specializes in Italian food.

In general the meal is stingy, but the tiramisu is

perfect. The restaurant decoration is kitsch with

standard furniture. This opon does not explain

whether kitsch is intentional or just a derogatory

judgment. The service is extremely slow.

A schematic graphical representation of the same

opinion ontology is seen in Fig. 1.

2.2 Sharp Recommendations

The current usage of recommendation web-sites has

several disadvantages:

Long texts – one must read a considerable

amount of text in order to get an overall,

frequently vague, idea about the review;

Low keyword density – one needs to manually

search to eventually extract a too small

amount of important keywords;

Bias and irrelevance – opinions often focus

on arbitrary or low probability events, such as

the specific direction or smaller size of a

particular room in a big hotel.

In contrast, short opinion ontologies intend to

enable rapid winnowing of the undesirable features

listed above and to provide a sharp view of the

expressed opinion.

2.3 Rational Decisions in Short Time

Opinion ontologies can be used as a direct source of

information to make fast rational decisions, as opons

are sharp and short.

For instance, positive reasons for booking a table

at Don Giovanni’s (by opon #28, above Fig.1)

would be a special love for Tiramisu and

indifference to kitsch. Reasons for not booking a

table could be the stingy meal and being in a hurry.

Opinion ontologies can be the input to reasoning

systems, which by comparison to a domain ontology

or by means of rule-based inference, could for

instance conclude that “white tablecloth and

napkins” imply a more expensive bill.

Finally, one could integrate off-line various opinion

ontologies into a single one, in order to make later

on inferences in a shorter time.

“opon #28: rest Don Giovanni loc downtown

food Italian, stingy meal, perfect tiramisu déco

kitsch, standard serv extremely slow.”

Opinion-Ontologies-ShortandSharp

455

3 OPINION ONTOLOGY

PROPERTIES

We here propose opinion ontologies having some

specific syntactic characteristics.

The opinion ontology is supposed to be purely

textual – without any graphical elements or colors.

The opinion ontology is always initiated by an

“opon” term and terminated by a full stop. In

between there are only words and separators

(comma or semicolon).

An opinion ontology consists of two kinds of

terms: class terms, of at most four letters (marked by

italic-bold, here in red for the online digital reader

convenience) and free-text words. Class terms are

not reserved words of a language. They rather could

be explained in a glossary and systematically used

within an application.

An opinion-ontology has as a size parameter an

upper bound to the allowed number of characters

(letters, numbers, signs) used.

Next we point out semantic and operational

characteristics of opinion-ontologies.

3.1 Sharp

Our proposed opinion-ontologies are intended to be

sharp information conveyors due to a few features:

Absence of stopwords – there is no need to

filter low information content words;

Absence of sentence structure – there is no

need to follow standard natural language

grammar, leading to parsimonious

expression;

Imposed opon structure – the linearized tree

structure facilitates reading and fast updating

of the opinion-ontology.

Once people get used to the opon structure, their

manipulation by humans will be increasingly

efficient. Of course, opinion-ontologies are easily

amenable to computerized manipulation.

3.2 Tweetable

By tweetable we mean a quite small and strict upper-

bound to the number of characters in the opinion-

ontology.

We do not mean the specific 140 character limit

of the Twitter social network.

The above referred upper-bound is a parameter to

be assigned in specific applications.

The reasons for the “tweetable” upper bound are

both practical – say the actual usage of tweeter by an

added URL – and deeper semantic arguments.

If one is forced to perform off-line compaction

analysis, before sending an opinion-ontology, one

gains information and semantic density. One thus

transmits more interesting information.

3.3 Subjective

In contrast to a typical domain ontology that is

assumed to represent the common vocabulary and

shared meanings of the domain, an opinion-ontology

is clearly subjective.

It is not necessarily subjective in an individual

sense. It could represent some group or a large

section of public consensus, but still subjective and

even being opinionated.

An opinion-ontology is an ontology, not due to

the overall domain agreement, but due to its

selective semantic character.

4 MERGING AND INFERENCE

OPERATIONS

Merging and inference are two central operations on

opinion-ontologies. Their importance stems from

two fundamental principles:

a. Size Conservation – independently of the

number of merged opinion-ontologies, the

outcome should be a standard opon with the

same syntactic and operational properties as

the original merged opons, e.g. same size

parameter;

b. Semantic Equivalence – an inference

operation on a set of opons should obtain a

semantically equivalent outcome opon.

Merging of Opinion-Ontologies

We now give a sample of merging rules for

opons. First, numerical simplification rules are

given:

a. Reinforcement – when a few

recommendations state the same opinion, use

a numerical weight to express it, say *4

means that the opinion appeared four times

in the merged opons;

b. Contradictions – in case of opposing

opinions use positive and negative weights,

e.g. *-5 *3 (five negations and 3

affirmations);

c. Excess Words – discard the less surprising

(less informative) words within the excess

words of the merging opons.

Next, rules are related to semantic characteristics:

KEOD2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeEngineeringandOntologyDevelopment

456

d. Different terminologies – choose the most

frequent term among the different ones;

e. Ambiguities – disambiguate terms using

opons before they are merged;

5 CASE STUDIES

5.1 Restaurant Recommendation

Here we report the following experiment. We looked

at a restaurant recommendation web-site. The

recommendations were of free text with a typical 50

words length and about 5 keywords categorization.

We took a small sample of these

recommendations and condensed them into the

opinion-ontology format, as follows:

We made a series of worthwhile observations

from this sample. Some of them are:

a- Semantic content – there is an obvious

semantic character to these opons, which may

be used for making inferences; they are not

just dry facts on eating meals;

b- Connotations – classical wood furniture,

Retro touches and take-away do have

implications about food and quality;

c- Branding names – chosen for branding, e.g.

Post-Modern in the Museum of Art, but

induce expectations on food and enable

inferences about quality and price;

d- Incompleteness – classes may lack property

instances, say the last opon serv; but these

may be completed later on.

5.2 Hotel Recommendation

Hotel recommendations – e.g. those in web-sites

offering travel advice – have more complex

characteristics than restaurant recommendations.

Essentially one could have a quite similar structure

as:

In this example the hotel name is “The Hotel”, it

is conveniently located near a metro station, the

neighbourhood is not very recommendable, the room

has air conditioning and it is clean. The amenities

include sauna, and an unreliable wi-fi. The service is

friendly, but overall pricey.

This example shows that the language is quite

fuzzy, leaving a lot of margin for interpretation. For

instance:, it is not precise about the distance to the

metro station; so-so location is probably negative,

but may be acceptable for a given budget.

Summarizing, the loosely structured

information may still be quite challenging.

6 DISCUSSION

This paper proposed opinion-ontologies, short,

sharp, tweetable opinions loosely structured as a

small ontology tree.

The motivation for opinion-ontologies is both:

efficiency of information transmission and deeper

concerns with high density of important information.

The case studies reveal some interesting

observations. The restaurant booking case study,

shows clearly that opinion mining and understanding

is inherently not syntactically based upon presence

of positive words like “nice” or negative words as

“nasty” – agreeing with (Cambria, 2010).

Opinions are subtly expressed through

sophisticated expressions such as “Retro touches”,

eminently context dependent.

6.1 Are Opinion-Ontologies Real

Subjective Ontologies?

We are asking here two different but related

questions:

1. Are opons real ontologies?

2. Are opons subjective ontologies?

In order to answer the first question we cite the

ontology definition by Gruber (Gruber, 1993): an

ontology is a specification of a representational

vocabulary for a shared domain of discourse. The

important points seem to be the “specification of a

“opon #31: rest The Steak House loc

neighborhood food meat, grill déco classical

wood furniture, Retro touches serv meticulous.”

“opon #34: rest The Coffee Network loc

crossroads food take away, coffee house,

breakfast déco standard serv efficient.”

“opon #39: rest Le Bistro loc downtown food

French, gourmet, chef déco dim room serv

culinarian trip.”

“opon #42: rest Post-Modern loc Museum of

Art food chef, meat, pasta, vegetarian déco post-

modern serv.”

“opon #52: hotl The Hotel loc near metro stop,

so-so location room air condition, clean amen

sauna, wi-fi unreliable serv friendly, pricey.”

Opinion-Ontologies-ShortandSharp

457

representational vocabulary” and the “shared”

aspect.

An opon satisfies both important points mentioned

above. It is a specification, it has a representational

vocabulary – although a limited partial one for a

given domain – and it is “shared” among people

expressing and receiving the recommendation.

The second question may be more controversial.

One may claim that an opon is just a set of instances

of clearly non-subjective domain ontology. But we

wish to provide two arguments against this

viewpoint. First, the fact that the domain ontology is

not subjective does not necessarily imply that the

opon also is non-subjective, because the essence of

subjectivity is its dependence on interpretation.

Second, the logic of opons is most probably non-

monotonic. For instance, ‘classical furniture implies

quality food’ is sometimes true, sometimes not.

6.2 Future Work

The next stage of this work is to implement, and test

the whole approach and run extensively a system

with the capabilities proposed here:

Compacting free text – into short and sharp

opinion-ontologies;

Merging opons – i.e. given two or more

opinion-ontologies, to merge their

information into a new unique one without

expanding the opon sizes;

Making inferences from opons – by using

rules such as a restaurant with “white

tablecloth and napkins” is more expensive

than another one in which tables are without

tablecloth.

6.3 Main Contribution

The main contribution of this work is the concept

and detailed characterization of opinion-ontologies,

for efficient transmission and manipulation of

recommendations.

REFERENCES

Akbar, Z, Garcia, J.M, Toma, I. and Fensel, D., 2014. “On

Using Semantically-Aware Rules for Efficient Online

Communication”, in Proc. 8th International Web Rule

Symposium (RuleML 2014), August 18-20, Prague,

Czech Republic.

Biagioli, C., 1997. “Towards a legal rules functional

micro-ontology”, in Proc. LEGONT’97 Workshop.

Cambria, E., Speer, R., Havasi,C. and Hussain, A., 2010.

“SenticNet: A Publicly Available Semantic Resource

for Opinion Mining”, in AAAI Fall Symposium, pp.

14-18.

Chang, E., Hussain, F.K. and Dillon, T., 2005.

“Reputation ontology for reputation systems”, in

SWWS International Workshop on Web Semantics,

pp. 957-966, Springer-Verlag. DOI:

10.1007/11575863_117.

Exman, I., 2012. “A Non-Concept is Not a ¬Concept”, in

Proc. KEOD Conference, pp. 401-404. DOI:

10.5220/0004149704010404.

Exman, I., 2013. “Misbehavior Discovery through Unified

Software-Knowledge Models”, in CCIS, Vol. 348, pp.

350-361. Springer-Verlag. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-

37186-8_23.

Gruber, T.R., 1993. “A translation approach to portable

ontology specifications”. Knowledge Acquisition 5

(2), pp. 199-220.

Kiciman, E., 2012. “OMG, I Have to Tweet That! A study

of factors that influence tweet rates”, in Proc. 6

th

Int.

AAAI Conf. on Weblogs and Social Media, pp. 170-

177.

Li, F. and Du, T.C., 2011. “Who is talking? An ontology-

based opinion leader identification framework for

word-of-mouth marketing in online social blogs”,

Decision Support Systems, Vol. 51, (1) pp. 190-197.

DOI: 10.1016/j.dss.2010.12.007.

Lu, Y., Duan, H., Wang, H. and Zhai, C.X., 2010.

“Exploiting structured ontology to organize scattered

online opinions”, in Proc. COLING’10, 23

rd

Int. Conf.

on Computational Linguistics, pp. 734-742.

Schema.org web site: http://schema.org/ Last visited

August 2014.

STI (Semantic Technology Institute) at the University of

Innsbruck, web site: http://oc.sti2.at/results/papers.

Last visited August 2014.

Toma, I., Fensel, D., Oberhauser, A., Fuchs, C., Stanciu,

C. and Larizgoitia, I., June 2013. “SESA: A Scalable

Multi-Channel Communication and Booking Solution

for e-Commerce in the Tourism Domain”, in Proc.

10th IEEE International Conference on E-Business

Engineering (ICEBE 2013), Coventry, UK.

Toma, I., Fensel, D., Gagiu, A.-E., Stavrakantonakis, I.,

Fensel, A., Leiter, B., Thalhammer, A., Larizgoitia, I.,

and Garcia, J.-M., November 2013. “Enabling

Scalable Multi-Channel Communication through

Semantic Technologies”, in Proc. IEEE/WIC/ACM

International Conference on Web Intelligence,

November 17-20, 2013, Atlanta, USA, IEEE

Computer Society Press.

Toma, I., Stanciu, C., Fensel, A., Stavrakantonakis, I. and

Fensel, D., 2014. “Improving the online visibility of

touristic service providers by using semantic

annotations”, in Proc. 11th European Semantic Web

Conference (ESWC'2014), 25-29 May 2014, Crete,

Greece, Springer-Verlag, LNCS.

KEOD2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeEngineeringandOntologyDevelopment

458