Business Model Design

An Evaluation of Paper-based and Computer-Aided Canvases

Boris Fritscher and Yves Pigneur

Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland

boris.fritscher@unil.ch, yves.pigneur@unil.ch

Keywords: Business Model Canvas, Computer-Aided Business Model Design, Guidelines.

Abstract: In recent years, Business Model Canvas design has evolved from being a paper-based activity to one that

involves the use of dedicated computer-aided business model design tools. We propose a set of guidelines

to help design more coherent business models. When combined with functionalities offered by CAD tools,

they show great potential to improve business model design as an ongoing activity. However, in order to

create complex solutions, it is necessary to compare basic business model design tasks, using a CAD system

over its paper-based counterpart. To this end, we carried out an experiment to measure user perceptions of

both solutions. Performance was evaluated by applying our guidelines to both solutions and then carrying

out a comparison of business model designs. Although CAD did not outperform paper-based design, the

results are very encouraging for the future of computer-aided business model design.

1 INTRODUCTION

In a fast-evolving business landscape, companies

need to turn to new methods to help them rethink

their business strategy. By using a Business Model

Canvas (BMC), they can get a better picture of their

current business model, as well as create new ones.

These methods are gaining in popularity, leading to

the creation of a range of tools to support them.

Thus, BMC design has evolved from being a paper-

based activity to being one that is supported by

custom-built computer-aided business model design

(CABMD) tools. Such tools provide functionalities

that are similar to the paper experience, but offer

additional options such as version handling and

calculation. However, in order to give free rein to

creativity, the tools tend to be open in nature,

making them difficult to use in a structured

environment in which software tools are used. This

is especially the case if the application is expected to

assist the model itself. Guidelines can help by

capturing and encapsulating knowledge that has

been collected from best practice. This knowledge

can then be offered to users. Elaborating guidelines

helps in the design of more coherent business

models; in turn, this helps to improve the way in

which CAD can support business model design.

Nonetheless, all these advanced CAD tools, which

are aimed at supporting the BMC, are worthless if

they hinder the creative-thinking process enabled by

the paper version. However, if evaluation can show

that a digital canvas is perceived and performs at

least as well as a paper-based canvas, this promises

great potential. For example, some features, such as

automated guidelines validation, are only possible

with digital tools.

The focus of this research can be summarized by

the following questions:

Can guidelines help to produce a more coherent

business model canvas?

How does using a computer-aided business

model canvas design tool affect perception

compared with using a paper-based version?

How does using a computer-aided business

model canvas design tool affect performance

compared with using a paper-based version?

In the next section we present any justificatory

knowledge, followed by a short description of our

methodology. We then present the guidelines

themselves and the way in which they can be

supported by CAD. Our evaluation also includes a

business model case and an experiment aimed at

comparing paper-based design with CAD. The

results are presented, along with any lessons learned.

236

Fritscher B. and Pigneur Y.

Business Model Design An Evaluation of Paper-based and Computer-Aided Canvases.

DOI: 10.5220/0005426602360244

In Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design (BMSD 2014), pages 236-244

ISBN: 978-989-758-032-1

Copyright

c

2014 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2 DESIGNING BUSINESS

MODELS

According to Osterwalder and Pigneur (2013) there

are three areas where IS research can contribute to

strategic management. First, modelling at a strategic

level requires a common language and

representation. One business model visualization in

particular is starting to be widely adopted by

practitioners: the Business Model Canvas (BMC)

(Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010).

Second, the strategizing process should be seen

as a design activity. Here, design means elicitation

and testing; namely, the generation of ideas and their

validation.

Third, they put forward the idea that CAD can

“make tasks easier and quicker, while revealing as-

yet-unseen opportunities” (Osterwalder and Pigneur,

2013).

For the purpose of our study, testing in business

model terms represents two things: 1) coherence of

the business model and 2) commercial viability of

the business hypothesis. In this paper, we will focus

on the former, since it can be addressed by CAD

tools.

2.1 BMC Evaluation

The BMC design activity is usually a team effort

that involves stakeholders across the company. A

recent survey

1

of 1,172 users confirmed that 74% of

them carry out design in groups of 2 to 10

collaborators. Moreover, from research undertaken

by Reinig (2003: 65), we know that “the satisfaction

users have with the processes and outcomes of the

teamwork itself often determines the ultimate

adoption and sustained use of collaborative

technologies”. Therefore, it is important to compare

users’ perceptions of paper-based BMC with its

computer-aided counterpart.

To date, few studies have sought to evaluate

BMC design. However, Hoffmann et al. (2012) have

shown that paper-based BMC design outperforms

two other idea generation methods considerably.

They noted that: “The ability to select the best idea

was found to be much higher when groups worked

with the business model canvas: 80 per cent of

groups selected the best idea”. Their decision to

limit their study to paper-based design was based on

the extensive training and potentially expensive

support systems required by electronic methods.

In their research, Lucassen et al. (2012) focused

on how business model methods can be supported

1

Internal survey, Business Model Foundry GmbH 2012

by software. They came to the conclusion that,

“BMC is the preferred method because it effectively

models explicit information of both tangible and

intangible aspects of the business and communicates

this information in a highly accessible manner to

parties unfamiliar with the modeling technique”.

However, they did point out that there is still room

for improvement, because of a lack of clarity in the

modeling process. Furthermore, they pointed out

that knowing when the model is sufficiently correct

is not explicit. This sustains the relevance of

providing better business model design guidelines.

3 A DESIGN SCIENCE

APPROACH

In this study, we used the methodology put forward

in design science research by Gregor and Hevner

(2013). First, we explored how CAD can best

support business modeling. This was carried out

iteratively by building and evaluating prototypes.

We also focused on the evaluation of the perception

and performance of CAD business model design in

comparison with paper-based design. We used

existing artifacts such as the BMC and CABMD

tools. Our evaluation has one particularity in that we

chose to use a commercial instantiation of CABMD

software. However, we did propose a new artifact in

the form of guidelines, with the intention of making

better use of them. The evaluation of this artifact is

done by validity. Demonstrating that a coherent

business model case can be created by following the

guidelines.

4 TOOLS FOR BUSINESS

MODEL DESIGN

To help in the design of a BMC we put forward

guidelines, aimed at helping both the elicitation of

new elements and the testing of coherence. These

guidelines could then be transformed into actionable

rules for use inside a CABMD tool.

4.1 BMC as a Paper-based Artifact

The BMC uses nine building blocks to represent a

business model. These building blocks can be

further grouped into four perspectives, as shown in

table 1. The main perspective is the offer (what we

do), which connects the client perspective (who we

do it for) and the activity perspective (how we do it).

Business Model Design - An Evaluation of Paper-based and Computer-Aided Canvases

237

Finally,

(how m

u

The

importa

n

which

h

facilitat

e

drawn u

s

the offe

r

p

erspect

i

the acti

v

Ta

b

Perspe

c

Offer

Client

(right si

d

Activity

(left sid

e

Financi

a

The

r

elicitati

o

A

. D

i

Any eli

c

go throu

element

s

not har

n

its stren

from di

ff

the financial

u

ch?).

positioning

o

n

t. Visually,

t

h

elps to stru

c

e

comparison

s

s

ing this met

h

r

is in the c

e

i

ve and reve

n

v

ity perspecti

v

b

le 1 Business

M

c

tive Que

s

What

d

e)

Who

?

e

)

How

?

a

l How

r

e are three

o

n of business

iscover busin

e

c

itation techn

i

u

gh the nine b

l

s

as if it were

n

ess the full

p

n

gth lies in t

h

ff

erent blocks.

Fi

g

perspective

o

f these nin

e

t

hey form se

p

c

ture the tho

u

s

between th

e

h

od. As can b

e

e

ntre; to the

r

n

ue stream,

w

v

e and cost str

u

M

odel Canvas

s

tion Bui

l

? Val

u

?

Cust

Dist

r

Cust

?

Key

Key

Key

much? Rev

e

Cost

guidelines w

elements on

t

e

ss model ele

m

i

que is appli

c

l

ocks one aft

e

a checklist.

H

p

otential of t

h

h

e connecte

d

u

re 1: Busines

s

deals with p

e

blocks is

v

p

arate group

i

u

ght process

e

business m

o

e

seen in figu

r

r

ight is the c

l

w

hilst to the l

e

u

cture.

Components.

l

ding block

u

e proposition

o

mer segmen

t

r

ibution channel

o

mer relationsh

i

resources

activities

partnerships

e

nue stream

structure

h

ich help in

t

he BMC.

m

ents

c

able. Many

u

e

r another an

d

H

owever, this

d

h

e model, bec

a

n

ess of ele

m

s

Model Canva

s

p

rofit

very

i

ngs,

and

o

dels

r

e 1,

lient

e

ft is

l

s

i

ps

the

u

sers

d

add

d

oes

ause

m

ents

at

l

Ad

d

b

lo

c

vis

u

dis

p

ess

e

the

the

de

p

vis

u

5

w

gui

d

4.

2

Te

s

of

c

b

lo

c

gui

d

4.2

Th

e

un

d

s

of Zumba Fit

n

B. Improve b

A good BM

C

l

east one ot

h

d

itionally, th

e

c

k has to be

r

u

al appeara

n

p

laying only

e

ntial role i

n

connectedne

s

story of the

b

C. Highlight

By using bi

g

p

ict the flo

w

u

alize the sto

r

w

e use an

d

elines.

2

BMC

C

s

ting a BMC’

s

c

ontrol point

s

c

ks and co

n

d

elines for ea

c

.1 Guideli

n

Elemen

t

e

se guidelin

e

d

erstandable

B

There is

n

ess.

u

siness mode

l

C

has all of its

h

er; there are

e

number of

r

easonable so

n

ce. This

i

those elem

e

the busines

s

s

s between el

e

usiness mode

business mo

d

g

arrows on t

h

w

of interact

i

r

y of the busi

n

example to

oherence

G

s

coherence i

n

on three lev

e

n

nections.

W

c

h.

n

es Applyin

g

s help in

m

B

MC.

only one ide

a

l

through con

n

s

elements co

n

e

no orphan

elements in

s

as not to ov

e

i

s accompli

s

e

nts that pe

r

s

model. Fur

t

e

ments helps

e

l.

d

el mechanics

h

e top of th

e

i

on, it is p

o

i

ness model.

I

o

illustrate

t

G

uidelines

n

volves the v

e

els: elements

,

W

e propose

a

g

to Any In

d

m

aintaining

a

a

per sticky n

o

n

ections

n

nected to

elements.

s

ide each

e

rload the

s

hed by

r

form an

t

hermore,

in telling

BMC to

o

ssible to

I

n section

t

he three

e

rification

,

building

a

set of

d

ividual

visually

o

te.

Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

238

Ideas are written with keywords, or

presented with a simple illustration.

The meaning of the element is

understandable by all stakeholders.

The element is a key component in

explaining the business model; indeed,

without it the business model cannot be

explained.

4.2.2 Guidelines Applying to Individual

Building Blocks

These guidelines help to identify the right amount of

detail for the BMC.

All nine building blocks of the model are

used, or have at least been considered.

Elements that are too detailed have been

grouped into a simpler element.

Elements that are too generic have been split

into more detailed elements.

The detail level of the elements are adequate

(there are not too many detailed elements,

nor to few which are too generic).

4.2.3 Guidelines Applying to Connections

between Elements in Different

Building Blocks

These guidelines help with the coherence of the

BMC.

Colors are used on elements to highlight

their connections according to the BMC’s

meta-model (Fritscher and Pigneur, 2010)

Each color is labeled and has a specific

meaning.

Client perspective is valid:

- Each customer segment is addressed by

one or more value proposition.

- A channel supports a value proposition-

customer segment set.

- If present, a customer relationship

targets a customer segment.

- In case of multiple customer segments,

colors distinguish each business side.

Activity perspective is valid:

- Each value proposition is

produced/delivered by a key activity, a

key partner or offers a key resource.

- Key resources or key partners support

an activity.

Financial perspective is valid:

- Revenue stream is generated from a

value proposition-customer segment set.

(A revenue stream can also be “free”).

- Major fixed costs are listed.

- Major variables costs are listed.

There are no orphan elements: all elements

are connected to another element (in a

different block to themselves).

4.3 BMC Computer-Aided Design

Multiple versions of BMC prototypes can be found,

as well as commercial versions. Research prototypes

emphasize advanced features; however, they lack

finesse in user experience. In order to make the best

comparison between a paper-based BMC and a

digital implementation, we chose to use Strategyzer,

a commercial version that is closest to the original

paper-based BMC. This commercial software

solution not only has a proven user-friendly

interface, it has the added advantage of being

inspired by the same original artifact ideas as our

research prototypes. Another benefit is that it has

calculation features which sit on top of the basic

functionality features, showing that integration is

possible without compromising the simplicity of the

user interface.

When Computer Aided Design (CAD) is applied

to the BMC, it can support elicitation by making it

easier to move, duplicate and rename elements.

Thanks to its digital properties, elements can also be

hidden and shown selectively, allowing for multiple

views of the same data. This enables the exploration

of business model variants, thereby further aiding

the elicitation process.

Beyond visual interactions, such software tools

can be used to support business model design with

features that are tailored to guarantee the coherence

of the meta-model on which they are built.

Guidelines can be transformed into rules, which can

then be tested by the tool. In case of incoherence, a

notification is shown on any invalid elements. Such

visual flags can, in addition, contain hints on how to

fix the problem or, at the very least, offer a reference

as to which rule or guideline was violated. The

computation is carried out automatically; thus, visual

flags appear as soon as something changes.

Guidelines allow a coherence score to be

attributed to each model; this score is based on the

number of fulfilled conditions.

4.3.1 Example Guideline Transformed into

Rules and Resolution Hints

Rule 1: There are not more than a specified number

(given by a threshold) of customer segment elements

with the same color.

Business Model Design - An Evaluation of Paper-based and Computer-Aided Canvases

239

Resolution Hint: Either merge elements that are too

detailed (building block guideline) or change colors

of element belonging to a different value proposition

to distinguish the segments (connection guideline).

Rule 2: A customer segment has to have a

corresponding value proposition element with the

same color as itself.

Resolution Hint: Create missing elements or add

right colors.

5 COMPARING COMPUTER-

AIDED DESIGN WITH PAPER-

BASED DESIGN

The focus of our evaluation is to compare a paper-

based BMC with one created using a computer-aided

design tool in terms of perception and performance.

In this section, we first present how we created a

business model for Zumba Fitness following our

guidelines. We then go on to present the

experimental setup, followed by the results and

statistics.

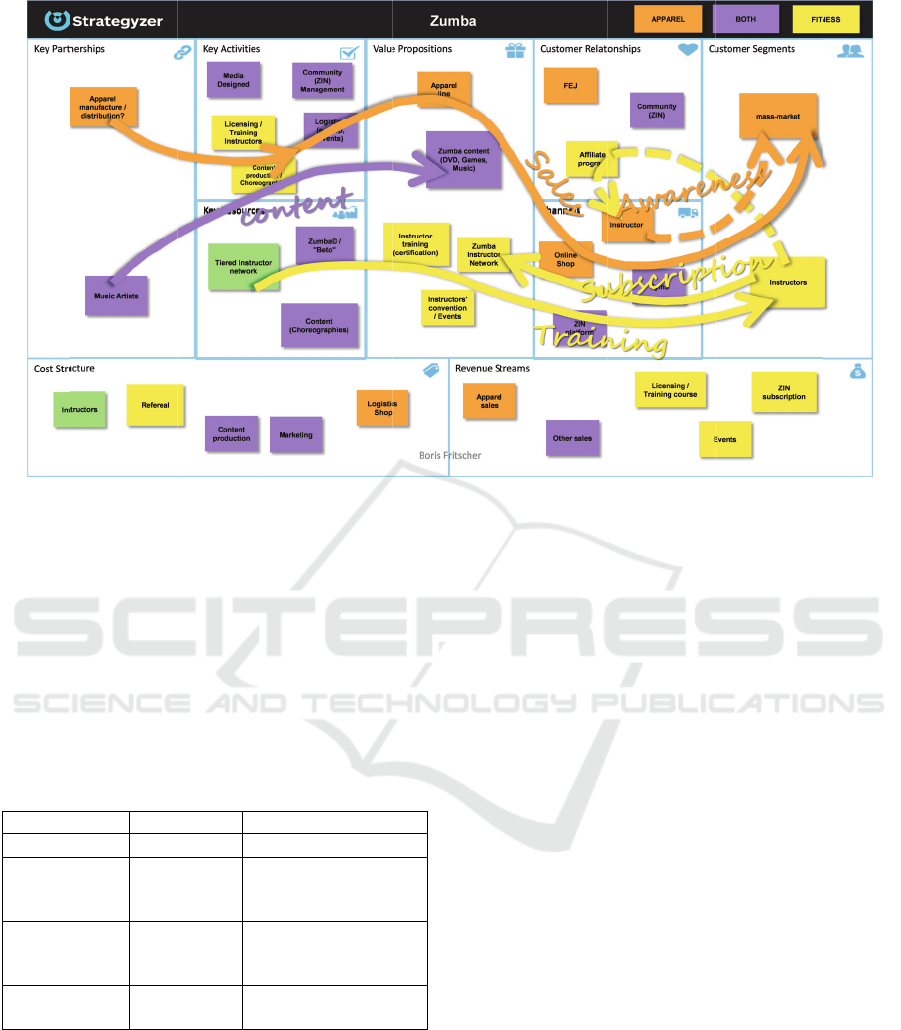

5.1 Zumba Fitness Business Model

This case is used to illustrate how to apply our

elicitation guidelines when designing the Zumba

Fitness business model using publicly available

information (as shown in figure 1). Zumba Fitness is

a company that offers fitness training to instructors

(yellow) and sells fitness apparel (orange) to the

mass market. Separate colors were used for each

type of offering. Elements that are affected by both

value propositions are shown in violet.

A. Discover Business Model Elements

The discovery of elements, which can be added to

any of the building blocks, can come from internal

knowledge, interview, observation or indeed any

kind of research method. However, it is crucial to

move from one idea to the next without limiting

oneself to one block at a time. Our main source of

information for this case study was a six-page report

by Inc magazine

2

and a video interview featuring

one of the company’s founders.

As should be the case for any presentation of the

BMC, we will first present the elements as a story,

instead of going through the blocks one at a time.

2

http://www.inc.com/magazine/201212/leigh-buchanan/

zumba-fitness-company-of-the-year-2012.html

Zumba Fitness offers Instructor training to the

instructors customer segment with the help of their

online ZIN platform and gyms. Giving courses

generates licensing/training revenues. A second

revenue stream from instructors is a subscription to

the ZIN network. This offer (value proposition) gives

the instructors access to new Zumba content which

they can use in their own Zumba classes. To provide

the aforementioned value propositions, a number of

key activities have to be performed, including

training, ZIN community management and creation

of new content (choreography).

Another customer segment is the mass market,

namely, people who buy apparel from the online

shop, thus generating sales revenue.

B. Improve Business Model through Connections

With any BMC, it is important to check the

connections between the elements. This helps to

identify any missing elements. It can also lead us to

question the validity of elements if no connection to

other elements can be found.

Continuing with our example, although fitness

apparel is sold, its source is missing. Therefore, for

coherence, manufacturing & distribution partners

had to be added, as well as a logistics and media

design activity, and the cost structure of a logistics

shop.

The content creation activity produces new

choreographies, not only as a value proposition, but

also as a new resource. However, to produce such

choreographies, the company also needed music

artists; these become a new partner element. The

creation of content (content production) is also a

major cost in the business model. An additional

resource, which gives value to their content, is the

Zumba brand name.

C. Highlight Business Model Mechanics

Business Model mechanics help to visually illustrate

major interactions between elements on the BMC.

The flow of the interaction is depicted by large

arrows, which connect the elements. Thinking about

the mechanics and the story behind it will help

reveal additional element interaction, which may not

emerge when looking only at individual elements.

This case is particularly interesting, because a

series of mechanics helps to reveal that instructors

are also a channel. Zumba starts by

training/certifying instructors; a major percentage of

these instructors will then subscribe to the Zumba

Instructor Network. A certified instructor goes on to

give Zumba courses and naturally starts to promote

Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

240

Table 2: Descriptive statistics.

Variable Mean Std. Dev. Min Max

Tool

P S P S P S P S

Perceived Usefulness 2.38 1.83 0.98 0.69 1.25 1.00 5.00 3.50

Perceived Ease of Use 2.36 1.80 1.13 0.73 1.00 1.00 6.00 4.00

Task Outcome 2.27 1.85 0.80 0.72 1.00 1.00 4.33 3.33

Task Innovation 2.17 2.79 0.73 1.10 1.00 1.00 3.00 4.67

Total Elements 23.00 28.82 5.75 6.91 11.00 20.00 32.00 42.00

Correct Elements 16.81 15.64 2.62 3.91 13.00 11.00 20.00 25.00

P: Paper (21 observations), S: Strategyzer software (22 observations)

Table 3: Pearson's correlation between concepts.

PU PEU TO TI TE CE

Perceived Usefulness [PU] 1.00

Perceived Ease of Use [PEU] 0.54*** 1.00

Perceived Task Outcome [TO] 0.27 1.00

Perceived Task Innovation [TI] 0.39** 1.00

Total Elements [TE] -0.28 -0.26 1.00

Correct Elements [CE] -0.32* 0.43** 1.0

P>|t| *** 0.001, ** 0.01, * 0.05

the brand and its apparel. To build on this

phenomenon, Zumba offers them an affiliate

program (customer relationship). Thus, through

awareness generation, instructors become a channel

to the mass market. This supports the second

mechanic, which is the sale of fitness apparel

through the online shop. The third mechanic can be

found backstage, in the form of generating content.

Having added instructor as a channel and an

affiliate program, it is then necessary to check again

for any connections. In turn, this reveals that, to

retain coherence, a referral fee has to be added to the

cost structure. This demonstrates the need to iterate

through the mentioned techniques and guidelines

until everything is in a stable and coherent state.

5.2 Experiment Setup

Our experiment was aimed at designing a business

model for the Zumba case using an article and a

video interview as information resources. The

evaluation was performed during a business model

course attended by students from a master’s program

in IS. The students were all familiar to a similar

level with the BMC method and web tool. A total of

43 students participated. They were split into 22

groups in order to have the most groups possible and

avoid students having to do the task individually.

Having teams of two people is a key component of

generating creative ideas (Paulus 2000) and

corresponds better to the normal use of the BMC.

Half of the groups were asked to do the design

task using a paper-based BMC. The others used the

chosen computer-aided business model design

software and were not allowed to use paper at all.

Evaluation of the task was carried out in two

parts. First, when a group considered their work to

be complete, each student was asked to individually

fill out a questionnaire to assess their perception of

the task. Second, all BMCs were collected and

evaluated to assess the performance of the groups’

designs.

5.3 Results and Statistics

In this section, we present our measures of

perception and performance, followed by their

statistical analysis.

5.3.1 Measurement of Perception

For the questionnaire we decided to use questions

and scales taken from existing literature (see

appendix for the full question list). The concepts of

perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use were

adopted from TAM (Davis 1989). However, we

simplified the questionnaire, reducing the number of

questions by removing those with similar meanings,

to avoid confusion amongst our non-native English

speakers.

A measure of the perceived task outcome was

added so that we could test whether there is a

difference in perception between the two medias. In

Business Model Design - An Evaluation of Paper-based and Computer-Aided Canvases

241

addition, this allowed us to make a comparison with

the real outcome performance metric. The task

outcome was adapted from Briggs et al. (2006).

Here, we selected items from their meeting outcome

and meeting process questions.

We were also interested in how media type

impacts our perception of being able to generate

ideas. For task innovation we used questions taken

from (Torkzadeh and Doll, 1999).

All answers have a seven-point likert scale,

which we coded from 1 (best) to 7 (worst).

In order to analyse the concept, for each question

we grouped the answer variables of each metric into

a usable concept (latent variables) using Cronbach's

alpha. The perceived usefulness concept is well

defined by its four questions with an alpha of 0.75.

For the perceived ease of use, we dropped question

number 2.3 to get a better alpha of 0.71. For the task

outcome concept we had to drop question 4.3 to get

an acceptable alpha of 0.75. The task innovation

concept is well described by its three questions with

an alpha of 0.92.

5.3.2 Measurement of Performance

The designed business model’s performance was

computed by comparing it with the solution

developed by two experts who followed the

techniques and guidelines presented in the artifact

section. A total of 28 points could be achieved for

the Correct Element measure. The comparison

points were not all a direct match; if an element was

similar in meaning to the solution, it was also

accepted. There were no negative points for

additional elements and the same evaluator corrected

all of the BMCs. We also took into consideration the

metric of the Total Elements in order to measure any

differences in quantity generation between the

media.

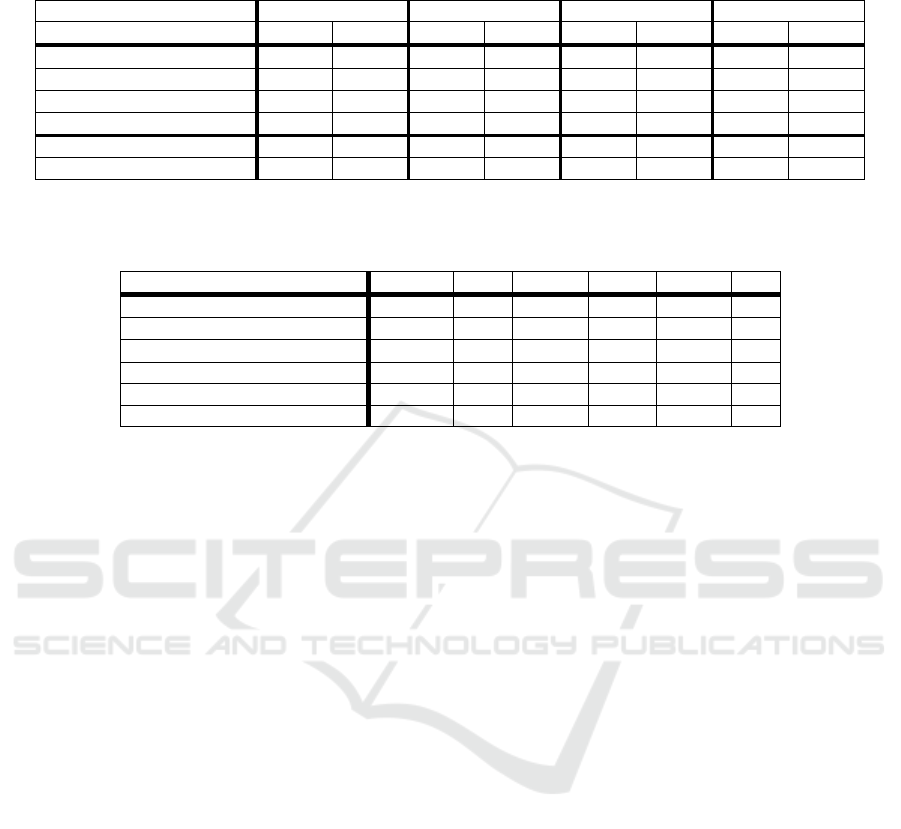

5.3.3 Descriptive Statistics of Results

As can be seen in table 2, answers are skewed

positively, with a low average score for all the

perception constructs. This indicates that overall the

students had a very positive perception of the BMC,

irrespective of the type. The computer-aided canvas

was marginally better than the paper-based canvas

on all the perception measures, except for task

innovation. It also helped to generate more elements.

Correct elements are very similar for both types.

Element metrics of the computer-aided canvas

showed the greatest deviation, with both the best and

the worst number of correct elements.

5.3.4 Statistical Analysis of Concepts

We used the Stata 12 software package to perform

our statistical analysis. After verifying the concept’s

alpha values we looked at the Pearson correlation

between them. The matrix, which can be seen in

table 3, helped us select the concepts that warranted

further analysis with regressions to determine the

impact of the type of media used.

The strongest correlation is between usefulness

and ease of use, which matches TAM’s theory. The

correlation between the total elements and correct

elements also seems natural. We did not penalize

wrong elements, therefore the more there are, the

greater the possibility of also having correct ones. Of

particular interest is the correlation between task

innovation and task outcome, and between task

Perceived

Innovation

Perceived

Ease of

Perceived

Usefulness

Total

Elements

Perceived

Outcome

Correct

Elements

P>|t| *** 0.01, ** 0.01, * 0.05

T

yp

e S: contribution of CAD

0.43***

R: 0.33

Type S: -0.68***

0.44**

R: 0.32

Type S: -

0.30**

R: 0.34

Type S: -2.92***

-1.13*

R: 0.10

Type S: -

R: 0.10

Type S: -0.55*

R: 0.10

Type S: 0.61*

R: 0.17

Type S: 5.8**

Figure 2: regressions between concepts.

Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

242

innovation and correct elements, which represents

the real outcome. We explore these relations further

in the discussion.

6 LESSONS FROM THE

COMPARISON

A regression analysis was used on the variables for

which correlations stood out. The results are shown

in figure 2. Only links with significant regression

results are shown. Type S is the contribution of

using the computer-aided software BMC over the

paper-based BMC. As already observed, with the

mean values, perceived innovation is slightly better

with the paper-based BMC, but the R-square value is

only 0.10. On the other hand, perceived innovation

strongly predicts perceived outcome. Users of the

digital BMC perceived that it helped them do a

better job more than did the users of the paper-based

BMC. Perceived innovation slightly predicts real

outcome (correct elements), without a difference

between types.

On its own, perceived usefulness is seen as being

better with the digital tool. This could be a bias of

the population of IS students who are familiar with

IT technology and might prefer a technical solution

to one that uses paper.

There is no significant difference between the

type that affected the influence of perceived ease of

use over perceived usefulness. This can be seen as a

positive result for the software tools, because it does

not perform better or worse. Having at least the

same ease of use as paper is a key result, which

should be reflected upon when considering that the

digital tool has the potential of offering additional

features, providing usefulness that is not possible on

paper.

The computer-aided BMC helps to generate

more elements than a paper-based one; however, it

also has a negative influence on the number of

correct elements. It is easier to generate more

elements, but also to generate more wrong elements.

Users who think that the digital tool helps them

innovate, think they have performed better;

however, in our small setup they obtained similar

numbers of correct elements.

In addition to the statistical analysis, we also

observed how the teams worked during the design

task. One observation that is of particular interest

relates to the process of eliciting elements. On the

paper-based BMC, a discussion first occurs and then

a sticky note element is created and positioned. On

the computer-aided BMC, however, which also

supports collaboration, elements are added first by

each member and then changed to reflect the

consensus. This is interesting because recording the

decision inside the tool means that it can be utilized

to better support the ongoing business modeling

collaboration process.

Three weeks after the first task, we carried out a

trial experiment with the coherence guidelines using

paper. The results were varied and inconclusive,

although users did say it helped them improve their

model. Problems arose when attempting to test them

on paper. In this situation, users have to perform the

checks manually; in some instances, they do not take

the time to iteratively do it as soon as they change

something. Therefore we posit that although we

showed that guidelines can be used to create

coherent models on paper, it is more appropriate for

such guidelines to be implemented and tested inside

a prototype tool. Here, they can be recomputed each

time a change is detected.

In summary, in our experiment with our test

group, the tested CAD tool was as effective as

paper-based design for the creation of business

models in terms of eliciting elements of the BMC.

This indicates that with the help of rules, it might be

better suited for testing the coherence of business

models than paper-based design.

7 CONCLUSIONS

To assist BMC design using software tools, we

proposed guidelines that help with elicitation and

testing in order to produce coherent models. Before

implementing such features in a digital tool we

needed to confirm that perception and performance

on a basic BMC design task are at least similar to

those of a paper-based design. With our evaluation

we found that the tested digital tools can be

perceived as useful, and does not perform any worse

than its paper-based alternative. Even if CABMD

did not outperform paper-based design, it shows

some promising results, because such tools can be

extended to offer additional features, thus increasing

their usefulness. Features that are much better suited

for digital tools include the continuous reviewing of

coherence rules to check their validity.

In this paper, we focused on modeling an

existing “as-is”, business model. Further research is

needed to explore options that may enable the

exploration of future “to-be”, business models. For

example, rules could be extended to simulate

financial assumption or validate regulatory

constraints.

Business Model Design - An Evaluation of Paper-based and Computer-Aided Canvases

243

REFERENCES

Briggs, R. O., Reinig, B. A., & de Vreede, G. J. (2006).

Meeting Satisfaction for Technology-Supported

Groups an Empirical Validation of a Goal-Attainment

Model. Small Group Research, 37(6), 585-611.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease

of use, and user acceptance of information technology.

MIS quarterly, 319-340.

Fritscher, B., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Supporting Business

Model Modelling: A Compromise between Creativity

and Constraints. Task Models and Diagrams for User

Interface, (LNCS 5963), 28–43.

Gregor, S., & Hevner, A. R. (2013). Positioning and

Presenting Design Science Research for Maximum

Impact. MIS Quarterly, 37(2).

Hoffmann, F., Eppler, M. J., & Bresciani, S. (2012).

Business Model Ideation: An Experimental Approach

for the Evaluation of Team-based Methods. 12th

EURAM 2012 European School of Management

Lucassen, G., Brinkkemper, S., Jansen, S., & Handoyo, E.

(2012). Comparison of visual business modeling

techniques for software companies. In Software

Business (pp. 79-93). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model

generation: a handbook for visionaries, game

changers, and challengers. John Wiley & Sons.

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2013). Designing

Business Models and Similar Strategic Objects: The

Contribution of IS. Journal of the Association for

Information Systems, 14.

Paulus, P. (2000). Groups, Teams, and Creativity: The

Creative Potential of Idea-generating Groups. Applied

psychology, 49(2), 237-262.

Reinig, B. A. (2003). Toward an understanding of

satisfaction with the process and outcomes of

teamwork. Journal of Management Information

Systems, 19(4), 65-84.

Torkzadeh, G., & Doll, W. J. (1999). The development of

a tool for measuring the perceived impact of

information technology on work. Omega, 27(3), 327-

339.

APPENDIX

The following questionnaire was used for our

survey, either using Strategyzer or the paper canvas

as subject.

Based on your short experience with Strategyzer,

how would you rate the following statements when

thinking about using Strategyzer for future Business

Model Design Tasks?

The following seven point Likert scale was used:

extremely likely (1), quite likely (2), slightly likely

(3), neither (4), slightly unlikely (5), quite unlikely

(6) extremely unlikely (7)

1 Perceived Usefulness

1.1 Using Strategyzer to design business model

would enable me to accomplish the task

more quickl

y

.

1.2 Using Strategyzer would improve my

p

erformance in desi

g

nin

g

business models.

1.3 Using Strategyer would make it easier to

desi

g

n business models.

1.4 I would find Strategyzer useful fo

r

desi

g

nin

g

b

usiness models.

2 Perceived Ease of Use

2.1 Learning to operate Strategyzer to design

b

usiness models would be eas

y

for me.

2.2 I would find it easy to get Strategyzer to do

what I want it to do.

2.3 It would be easy for me to become skillful

at using Strategyzer to design business

models.

The following seven point Likert scale was used

for the next two sections: strongly agree (1), agree

somewhat (2), agree (3), neither (4), somewhat

disagree (5), disagree (6), strongly disagree (7)

Now evaluate your business model design task.

3 Task Outcome

3.1 I feel satisfied with the designed business

model.

3.2 I feel satisfied with the process used to

desi

g

n the business model.

3.3 With more time I could substantially

improve the desi

g

ned business model.

3.4 I had enou

g

h time to complete the task.

4 Task Innovation

4.1 Strategyzer helps me create new ideas.

4.2 Strategyzer helps me come up with new

ideas.

4.3 Strategyzer helps me try out innovative

ideas.

Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

244