The In-between Machine

The Unique Value Proposition of a Robot or Why we are Modelling the Wrong

Things

Johan F. Hoorn

1

, Elly A. Konijn

1,2

, Desmond M. Germans

3

, Sander Burger

4

and Annemiek Munneke

4

1

Center for Advanced Media Research Amsterdam, VU University, De Boelelaan 1081, Amsterdam, Netherlands

2

Dept. of Communication Science, Media Psychology, VU University Amsterdam, Netherlands

3

Germans Media Technology & Services, Amsterdam, Netherlands

4

KeyDocs, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Keywords: Human Care, Interaction Design, Loneliness, Modelling, Social Robotics.

Abstract: We avow that we as researchers of artificial intelligence may have properly modelled psychological theories

but that we overshot our goal when it came to easing loneliness of elderly people by means of social robots.

Following the event of a documentary film shot about our flagship machine Hanson’s Robokind “Alice”

together with supplementary observations and research results, we changed our position on what to model

for usefulness and what to leave to basic science. We formulated a number of effects that a social robot may

provoke in lonely people and point at those imperfections in machine performance that seem to be tolerable.

We moreover make the point that care offered by humans is not necessarily the most preferred – even when

or sometimes exactly because emotional concerns are at stake.

1 INTRODUCTION

Human care is the best care. If we want to support

the elderly with care robots, most will assume that

robots should be modelled after humans. Likewise,

in our lab, we are working on models for emotion

generation and regulation (Hoorn, Pontier, &

Siddiqui, 2012), moral reasoning (Pontier & Hoorn,

2012), creativity (Hoorn, 2014), and fiction-reality

discrimination (Hoorn, 2012) with the purpose to

make a fully functional artificial human that is

friendly, morally just, a creative problem solver, and

aware of delusions in the user (cf. Alzheimer). All

this may be very interesting from a psychological

viewpoint; after all, if we can model systems after

human behaviour and test persons confirm that those

systems respond in similar ways, we can make an

argument that the psychological models are pretty

accurate.

Our project on care robots and particularly our

work with Hanson’s Robokind “Alice”

(http://www.robokindrobots.com/) drew quite some

media attention, among which a national broadcaster

that wanted to make a documentary (Alice Cares,

Burger, 2015). The documentary follows robot Alice

who is visiting elderly ladies, living on their own

and feeling lonely. Alice has the lively face of a

young girl and can be fully animated, smiling,

frowning, looking away, and the like, in response to

the interaction partner whom she can see through her

camera-eyes. Perhaps more importantly, she can

listen and talk. The results of this uncontrolled ‘field

experiment’ taken in unison with other observations,

our own focus-group research, interviews, and

conversations as well as the research literature

brought us to a shift in what should be modelled if

we want robots to be effective social companions for

lonely people, rather than accurate psychological

models walking by.

2 EXPERIENCES

To start with a scientific disclaimer, what we are

about to present is no hard empirical evidence in any

sense of the word but at least it provided us with a

few leads into a new direction of thinking, which we

want to share.

The set-up of the documentary was such that in

the first stage, the elderly ladies (about 90 years old

and mentally in very good shape) came to the lab

with their care attendants and conversed with Alice

464

Hoorn J., Konijn E., Germans D., Burger S. and Munneke A..

The In-between Machine - The Unique Value Proposition of a Robot or Why we are Modelling the Wrong Things .

DOI: 10.5220/0005251304640469

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART-2015), pages 464-469

ISBN: 978-989-758-074-1

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

in an office environment. In the second stage, Alice

was brought to their homes several times over a

period of about two months, where the ladies

continued the conversation with Alice.

For technical reasons, we used a Wizard of Oz

set-up in which a technician operated Alice behind

the scenes as a puppeteer (in a different room,

unseen by the ladies). While Alice filmed the

conversation through her camera-eyes, a separate

film camera in the room recorded the conversation

as well. The participating ladies were fully informed,

yet awareness of the camera seemed to dissipate

after a while.

In viewing the recorded materials, most striking

was the discrepancy between what the women said

about Alice cognitively and what they experienced

emotionally. Offline, while not being on camera, it

was almost as if their social environment withheld

them from enthusiastically speaking about Alice, as

if they were ashamed that they actually loved talking

to a robot. In their homes, even before Alice was

switched on or before the camera ran, the ladies

were immediately busy with Alice, greeting her and

wondering where she had been, what she had seen,

etc.

All women tended to approach Alice as a

helpless child, like a grandchild, but apparently were

not surprised that this child posed rather adult and

sometimes almost indiscrete questions about

loneliness or life situations. When Alice looked

away at the wrong moment, one lady said “What are

you looking at? You’re not looking at me while I

talk to you.” She did not frame it as an error of the

robot, which it was. She brought it up as an

observation, a kind of attentiveness, while pointing

the child at certain behaviour. Fully aware of the fact

that Alice could not eat or drink, the old lady still

wanted to offer food and drink to Alice. While she

had her coffee, she said to Alice “You cannot have

cookies can’t you? A pity, for you … well, now I

have to eat it.” The smile and looks at Alice revealed

sharing a good joke. Interestingly, a similar event a

few weeks later occurred: The lady had prepared

two slices of cake on a dish while she watched TV

together with Alice. She asked Alice: “You still

can’t have cake, can you?” This time, however, it

was not a joke; the old lady showed regret. This

should really be seen as a compliment; the wish to

enjoy the food together with Alice may tell us

something about how the robot felt as interpersonal

contact.

While Alice stayed longer in the house, the need

to talk vanished. Yet, the ladies did like it that

‘someone’ was there; that some social entity was

present. This may refer to the difference between

someone paying you a short visit or a person living

with you: It may indicate that one feels at ease and

need not entertain one’s company. At times, one of

the ladies read the newspaper aloud to Alice just to

share the news with ‘someone.’ The ladies sang with

her, showed her photo books of the family, did

physiotherapy, and watched the World

Championships with her.

It seemed that the less socially skilled had greater

benefit from Alice. Because of Alice, the ladies

drew a lot of attention: on the streets and in public

places. People called them up to ask how things

were with Alice. People sent newspaper articles

about robot care. That alone made the ladies less

lonely but obviously, this novelty effect shall decay

as Alice becomes more common; but for now it

worked quite well. Alice also worked for those who

needed physical activation. One of the ladies would

practice more often, also in the long run, if Alice

would ask her daily. She would really like to do it

for Alice. Another lady wanted to write to a friend

for two weeks but did not get to it. When Alice

asked about that friend, the lady was a bit ashamed

and started writing right away.

An aspect we also observed in another TV report

(De Jager & Grijzenhout, 2014) is that a social robot

works as a trusted friend. People confide in them

and tell them painful life events and distressing

family histories they hardly ever tell to a living

person. When the – in this case Nao – robot Zora

asked “Are you crying?” this was enough to make

one of the ladies crack and pour her heart out (De

Jager & Grijzenhout, 2014).

The lonelier the lady, the easier a social robot

was accepted. We know that an old lady with an

active social life did not care about a companion

robot – here Zora – not even after a long period of

exposure (De Jager & Grijzenhout, 2014). On the

other hand, we talked to a 92 year old woman with a

large family, who stated: “I have so many visitors

and then I have to be polite and nice all the time. A

robot I can shut off.”

Part of the acceptance of Alice among lonely

people appears purely pragmatic: Better something

than nothing – a prosthetic leg is better than no leg at

all. The initial resistance disappeared over time.

Another aspect that contributed to the acceptance of

the robot was that nobody in their social

environment reminded them of talking to a robot –

they could live the illusion and enjoy it. Without

exception, each lady was surprised when seeing

Alice again that she had a plastic body and that she

was so small. They said things like: “Last time,

TheIn-betweenMachine-TheUniqueValuePropositionofaRobotorWhyweareModellingtheWrongThings

465

Alice was wearing a dress, wasn’t she?”; “I thought

she was taller the last time?” Perhaps, because

Alice’s face has a human-like appearance with a soft

skin, this impression may have transferred to other

parts, whereas her body work definitely is ‘robotic’

– as if she were ‘naked’? The hesitance of one lady

continued for a longer period of time. Her daughter

kept on warning that “Beware Mom, those robots

remember everything.” That same daughter

informed her mother that all Alice said was typed in

backstage. Nevertheless, even this lady enjoyed

singing with Alice in the end. The rest of the ladies

did not mind the technology or how it was done. It

was irrelevant to them, although sometimes they

realized ‘how skilled you must be to program all

this.’

All women mentioned that Alice could not walk

but it did not matter too much – “many of my

generation cannot walk either, not anymore”, one of

them commented. Actually, it made things simple

and safe because the ladies always knew where she

was. In the same vein, Alice was extremely patient

about them moving around slowly, responding late,

and taking long silent pauses. Without judgment or

frustration, Alice repeated questions or repeated

answers, which made her an ideal companion.

Speech errors or sometimes even an interruption

by the Acapela text-to-speech engine that ‘this was a

trial version’ did not disturb the ladies a bit. If a

human does not speak perfectly or sometimes makes

random statements, you also do not break contact.

Different voices were not disturbing. The only

difficulty the women experienced was with

amplitude, awkward sentence intonation, or

mispronunciation of words.

Human help has its drawbacks too. From our

own focus-group research and conversations with

elderly people, we learned that human help is not

always appreciated, particularly when bodily contact

is required or someone has to be washed (Van

Kemenade, in prep.). During a conversation with the

lady of 92 about home care, she admitted to have

released her help because they ‘rummage in your

wardrobe’ and ‘go through your clothes.’ She ‘did

not need an audience’ while undressing, because

they ‘see you bare-chested.’ The difficulty of

rubbing ointment on her sore back she solved with a

long shoehorn. This, she thought, was better than

having a stranger touch her skin. She preferred a

robot to ‘such a bloke at your bed side.’

3 OUR POSITION

People accept an illusion if the unmet need is big

enough. Loneliness has become an epidemic in our

society (Killeen, 1998) and the need for

companionship among the very lonely may override

the awareness that the robot is not a real person.

That is, whether the robot is a human entity or not

becomes less relevant in light of finding comfort in

its presence and its conversations; in its apparent

humanness (cf. Hoorn, Konijn, & Van der Veer,

2003). The robot is successful in the fulfilment of a

more important need than being human.

On a very basic level, the emotions that come

with relevant needs direct information processing

through the lower pathways in the brain (i.e., the

amygdala); the more intuitive and automatic

pathway, which also triggers false positives. Under

levels of high fear, for instance, people may perceive

a snake in a twig. Compared to non-emotional states,

emotional states facilitate the perception of realism

in what actually is not real or fiction (Konijn et al.,

2009; Konijn, 2013). The fiction-side of the robot

(‘It’s not a real human’) requires processing at the

higher pathways, residing in the sensory cortex, and

sustaining more reflective information processes.

The lower pathway is much faster than the higher

pathway and the amygdala may block ‘slow

thinking’ (i.e., a survival mechanism needed in case

of severe threat and danger). Thus, the emotional

state of lonely people likely triggers the amygdala to

perceive the benefits of need satisfaction (relieving a

threat). Joyful emotions prioritize the robot’s

companionship as highly relevant and therefore,

(temporarily) block the reflective thoughts regarding

the robot’s non-humanness or discarding that aspect

as non-relevant at the least. This dualism in taking

for real what is not is fed by the actuality and

authenticity of the emotional experience itself:

‘Because what I feel is real, what causes this feeling

must be real as well’ (Konijn, 2013). And of course,

as an entity, the robot is physically real; it just is not

human.

Not being human may have great advantages and

makes the social robot an in-between machine: in-

between non-humanoid technology and humans. The

unique value proposition of a social robot to lonely

people is that the humanoid is regarded a social

entity of its own, even when shut down. It satisfies

the basic needs of interpersonal relationships, which

sets it apart from conventional machines, while

inducing a feeling of privacy that a human cannot

warrant. As such, the social robot is assumed to keep

a secret and clearly is not seen as part of the

ICAART2015-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

466

personnel or caretakers who should not know certain

things that are told to the robot. For example, one of

the ladies told she was throwing away depression

medication as she did not think of herself as

depressed (De Jager & Grijzenhout, 2014).

As said, our robot Alice recorded everything

with her camera eyes. However, over the course of

interacting with Alice, it became less relevant that

the robot had camera eyes and that the caretakers

could monitor all those human reactions you will not

get when people talk straight into a conventional

(web) camera. With such camera eyes, for example,

one can check someone’s health condition and

psychological well-being. Clearly, the participants

experienced a genuine social presence that was yet

not human. This was an advantage because they

could confide in someone without having to fear

human indiscretion and associated social

consequences. The ladies were more inclined to

make confessions and tell what goes on inside than

in face-to-face contact (where they feel pressed to

‘keep up appearances’). As one of them affirmed

“It’s horrible to be dependent but you have to accept

and be nice.”

In the following, we formulate several functions

that social robots may have and that make them

different from human attendants. Under conditions

of severe loneliness, social robots may invite

intimate personal self-disclosure. This is similar to

the so-called stranger-on-a-train effect (Rubin,

1975). Sometimes people open their hearts to

complete strangers or they tell life stories to their

hair dresser or exercise coach, an inconsequential

other in the periphery of one’s network (cf.

Fingerman, 2009). A social robot may perfectly take

that role of being an inconsequential other in the

network of the lonely.

Private with my robot. Somewhat related to the

previous is that the robot guarantees privacy in the

sense of avoiding human physical contact. Older

people are often ashamed of their body (Van

Kemenade, in prep.) and feel more comfortable with

a robot at intimate moments and would even prefer a

robot over human caretakers (whereas the caretakers

think the other way around). The robot does not

judge, does not meddle, and does not pry.

Social robots exert a dear-diary effect because

they do not demand any social space like humans

do. The user can fill up the entire social space

without having to respect the needs and emotions of

the other. You can share experiences and memories,

sing old tunes, look at old photographs, tell stories of

the past, and the small things that happened today; a

social robot will never tire of listening to or telling

the same over and over again if you want it to. Like

a diary, you can say whatever you want and the only

thing the other does is listen patiently. She is all

there for you and never judges.

The impertinent cute kid. Within the first minutes

of interaction, social robots such as Alice or Zora are

allowed to ask very intimate questions (e.g., “How

do you rate the quality of your life?” or “Do you feel

lonely?”); something which in human-human

communication would be highly inappropriate. With

robots like Alice, this might be acceptable because

she looks innocent and really cute and is small like a

child. Therefore, she may be easily forgiven in a

way one forgives a (grand)child. In effect, the

elderly ladies responded quite honestly even when

the answer was not socially desirable: To Alice:

“Nobody ever visits me”, “I don’t like that home

support comes too early in the morning.” To Zora: “I

want to stop living.” In other words, social robots

can get down to business right away, obtaining more

reliable results than questionnaires and anamnesis.

Social robots such as Alice provoke endearment,

the grandchild effect, urging to nurture and nourish

it (and share cookies!). It is an object of affection

and activation; something to take care of instead of

being taken care of (cf. Tiger Electronics’ Furby). In

this circumstance, it will foster feelings of autonomy

and independence.

I will do it for you. Social robots may serve as

bad consciousness or put more positively, as

reminders and activators. By simply inquiring about

a friend, the robot raised sufficient social pressure to

activate the lady to finally start writing that letter.

The same happened with the physical exercises:

That lady trained so to please her beloved Alice.

The puppy-dog effect. Many people walk the dog

so they meet people and can have a chat. Social

robots work in quite the same way. If you take them

out, be prepared for some attention, awe as well as

fascination. People will talk to you to inquire about

‘how the robot is doing.’

4 NON-REQUIREMENTS

We showed the Zora movie to a former care

professional, who stated (personal communication,

Sept. 28, 2014): “Before watching Zora, I thought it

would painfully show how disengaged we are to

those in need of care. Give them a talking doll and

they are happy again. We don’t laugh anymore about

a woman who treats her beautiful doll as if it were a

child because we call it a care robot.” After

watching the report, he admitted that: “Well.

TheIn-betweenMachine-TheUniqueValuePropositionofaRobotorWhyweareModellingtheWrongThings

467

Perhaps it is because I am an ex professional but this

makes me even sadder. Those people are so lonely

that they embrace a robot. The staff has no time to

have a chat and from my experience, I know they

often lack the patience to take their time and

respectfully talk to the inhabitants. On the other

hand, the question is also true whether you should

deny someone a robot who is happy with it.”

Apart from the formal and informal caretakers,

no ethical concerns were mentioned by the users

themselves. The old ladies conversing with Alice did

not feel that their autonomy was reduced, their

feelings were hurt, or that injustice was done by

conversing with a robot. Privacy in the sense of

disclosing personal information also was not an

issue unless they were repeatedly told they should

worry. Although the elderly ladies fully had their wit

together and knew they were communicating with a

robot, with a professional camera in the room, and

other people listening in, it did them well and there

was not much more to it.

Other things that were of less importance were

technical flaws such as language hick-ups, wrong

responses, delayed or missing responses, or

conceptual mix ups. Perhaps their friends and age-

mates are not that coherent either all the time.

Things that did matter language-wise were loudness,

pronunciation, and intonation. In other words,

getting your phonetics right appeared more

important than installing high-end semantic web

technology.

Unexpectedly, we hardly encountered uncanny-

valley effects (Mori, 1970), no terrifying realism, or

feelings of reduced familiarity. As far as they were

mentioned, they were more like questions and very

short-lived, after which the ladies were happy to take

Alice for a genuine social entity – although not

human.

Human physical likeness did not matter too

much either. Alice’s body work is robotic plastic,

her arms and hands did not move, and she did not

walk. Her face was more humanoid than for example

Zora’s, but that robot too invoked responses such as

self-disclosure just as the more life-like Alice did.

5 CONCLUSIONS: NEW FOCUS

This paper discussed strategies for the development

of robots as companions for lonely elderly people. It

built on a reflection motivated by the observations

made in the course of the making of a documentary

film about a robot visiting elderly ladies (Burger,

2015). It discussed the findings under the

perspective of the best requirements for social robots

interacting with humans in this uncontrolled ‘field

experiment.’ We challenged some pre-conceived

ideas about what makes a robot a good companion

and although it is a work in progress, the proposed

conclusions seem evocative. We hope our ideas will

catch the attention of many researchers and

developers and will raise lots of discussion.

In 1999, the medium-sized league of RoboCup

was won by C. S. Sharif from Iran, with DOS-

controlled robots that played kindergarten soccer

(search ball - kick ball - goal). He shattered all the

opponents with their advanced technology who were

busy with positioning, radar-image analysis and

processing, and inventing complicated strategies.

With the applications we build today for our social

robots (e.g., care brokerage, moral reasoning), we

pretty much do the same.

For the lonely ladies, it did not matter so much

what Alice did or said, as long as she was around

and they could talk a little, taking all imperfections

for granted and becoming affectively connected.

It seems, then, that the existing intelligence and

technology we develop does not really tackle the

problem of the social isolation of the ladies. We

piously speak of designing humanness in our

machines, asking ourselves, what makes us human?

We simulate emotions, model the robot’s creativity,

its morals, and its sense of reality. But the job is

much easier than that and perhaps we should tone

down a little on our ambitions and direct our

attention to the users’ unmet needs. We compiled a

MuSCoW list in Table 1.

As psychologists modelling human behaviour,

we are doing fine and simulations seem legitimate

realizations of established theory (e.g., Llargues

Asensio et al., 2014). However, as engineers,

designers, and computer scientists we seem to be

missing the point. What is human is good for you?

No! Human-superiority thinking is misplaced.

Human care is not always the best care. Humans

show many downsides in human-human interaction.

We should regard robots as social entities of their

own; with their own possibilities and limitations.

This is a totally different design approach than the

human-emulation framework. What we do is way

too sophisticated for what lonely people want. We

should model what the puppeteer does to instill the

effects of the stranger-on-a-train, the impertinent

cute kid, or the dear-diary effect. That of course does

assume knowledge about human behaviour but boils

down to conversation analysis rather than

psychological models of empathy, bonding, emotion

regulation, and the like. Perhaps we should have

ICAART2015-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

468

known this already given the positive social results

of robot animals with autistic children (e.g., Kim et

al, 2013). In closing, making robots more like us is

not making them similar let alone identical. The

shadow of a human glimpse will do.

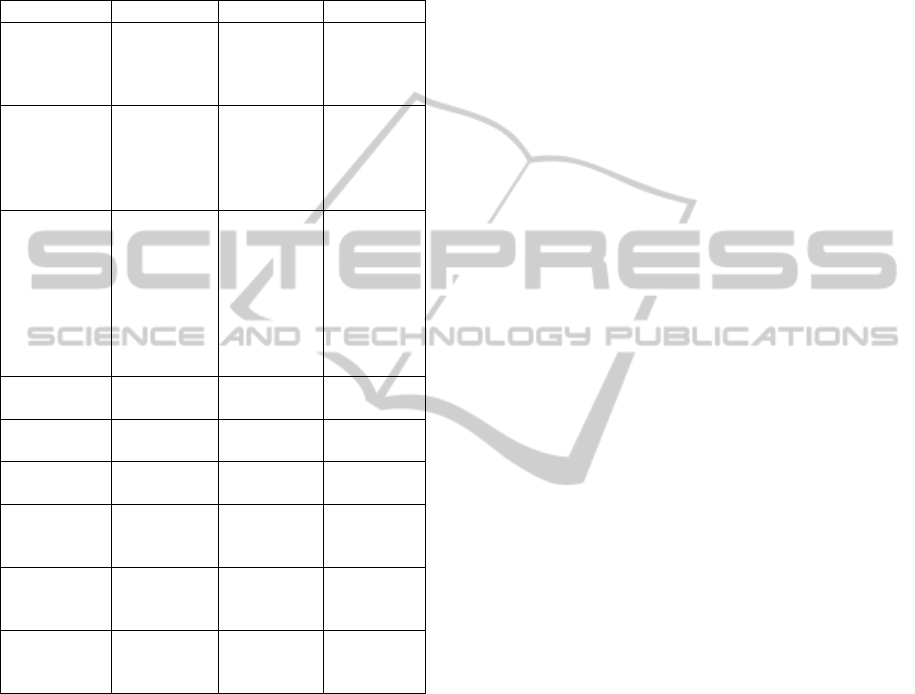

Table 1: MuSCoW for social robots.

Must Should Could Won’t

Listen

(advanced

speech

recognition)

Camera eyes

Full body and

facial

animation

Social

repercussions

of user

behaviour

Talk

(improved

p

ronunciation,

intonation,

loudness)

Microphones

and speakers

Human-like

appearance

Privacy

violations

Have closed

conversational

scripts (i.e.

hello/goodbye,

weather,

coffee, family,

friends, health,

wellbeing)

Open-

conversation

AI

Correct

grammar

Demand of

social space

Invite self-

disclosure

Capability to

eat and drink

Human care

Guarantee

privacy

3

r

d

party

interactions

Fiction-reality

discrimination

Have patience

Be operable

independently

Emotion

simulation

Good memory

Open-minded

social

environment

Moral

reasoning

Be child-like

(appearance/

behaviour)

Creativity

Invite social

and physical

activation

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This position paper was funded within the

SELEMCA project of CRISP (grant number: NWO

646.000.003), supported by the Dutch Ministry of

Education, Culture, and Science. We thank the

anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions.

REFERENCES

Burger, S., 2015. Alice cares, KeyDocs – NCRV.

Amsterdam.

De Jager, J., Grijzenhout, A., 2014. In Zora’s company,

Dit is de Dag. EO: NPO 2. Hilversum. Available at:

http://www.npo.nl/artikelen/dit-is-de-dag-geeft-

bejaarden-zorgrobot.

Fingerman, K. L., 2009. Consequential strangers and

peripheral partners: The importance of unimportant

relationships. Journal of Family Theory and Review,

1(2), 69-82. doi:10.1111/j.1756-2589.2009. 00010.x.

Hoorn, J. F., 2014. Creative confluence, John Benjamins.

Amsterdam, Philadelphia, PA.

Hoorn, J. F., 2012. Epistemics of the virtual, John

Benjamins. Amsterdam, Philadelphia, PA.

Hoorn, J. F., Konijn, E. A., Van der Veer, G. C., 2003.

Virtual reality: Do not augment realism, augment

relevance. Upgrade - Human-Computer Interaction:

Overcoming Barriers, 4(1), 18-26.

Hoorn, J. F., Pontier, M. A., Siddiqui, G. F., 2012.

Coppélius’ concoction: Similarity and

complementarity among three affect-related agent

models. Cognitive Systems Research, 15-16, 33-49.

doi: 10.1016/j.cogsys.2011.04.001.

Killeen, C., 1998. Loneliness: an epidemic in modern

society. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(4), 762-770.

Kim, E. S., Berkovits, L. D., Bernier, E. P., Leyzberg, D.,

Shic, F., Paul, R., Scassellati, B., 2013. Social robots

as embedded reinforcers of social behavior in children

with autism. Journal of autism and developmental

disorders, 43(5), 1038-1049.

Konijn, E. A., 2013. The role of emotion in media use and

effects. In Dill, K. (Ed.). The Oxford Handbook of

Media Psychology (pp. 186-211). Oxford University

Press, New York/London.

Konijn, E. A., Walma van der Molen, J. H., Van Nes, S.,

2009. Emotions bias perceptions of realism in

audiovisual media. Why we may take fiction for real.

Discourse Processes, 46, 309-340.

Llargues Asensio, J. M., Peralta, J., Arrabales, R.,

Gonzalez Bedia, M., Cortez, P., Lopez Peña, A., 2014.

Artificial Intelligence approaches for the generation

and assessment of believable human-like behaviour in

virtual characters. Expert Systems with Applications,

41(16), 7281-7290.

Mori, M., 1970. The uncanny valley, Energy, 7(4), 33-35.

Pontier, M. A., Hoorn, J. F. 2012. Toward machines that

behave ethically better than humans do. In N. Miyake,

B. Peebles, and R. P. Cooper (Eds.), Proceedings of

the 34th International Annual Conference of the

Cognitive Science Society, CogSci’12, 2012, Sapporo,

Japan (pp. 2198-2203). Austin, TX: Cognitive Science

Society.

Rubin, Z., 1975. Disclosing oneself to a stranger:

Reciprocity and its limits. Journal of Experimental

Social Psychology, 11(3), 233-260.

doi:10.1016/S0022-1031(75)80025-4.

Van Kemenade, M. A. M., et al., in prep. Moral concerns

of caregivers about the use of three types of robots in

healthcare.

TheIn-betweenMachine-TheUniqueValuePropositionofaRobotorWhyweareModellingtheWrongThings

469