Patient Empowerment as a Cognitive Process

Eleni Kaldoudi

1

and Nikos Makris

2

1

School of Medicine, Democritus University of Thrace, Dragana, Alexandroupoli, Greece

2

School of Educational Sciences, N. Chili, Alexandroupoli, Greece

Keywords: Patient Empowerment, Cognitive Process, Empowerment Model, Awareness, Engagement, Control.

Abstract: The concept of patient empowerment has emerged as a new paradigm that can help improve medical

outcomes while lowering costs of treatment by facilitating self-directed behavior change. Patient

empowerment has gained even more popularity since the 1990’s, due to the emergent of eHealth and its

focus on putting the patient in the centre of the interest. Current literature provides systematic reviews of the

area, and shows that well defined areas (or dimensions) have eventually emerged in the field. In this paper

we argue that patient empowerment should be treated formally as a cognitive process. We thus propose a

cognitive model that consists of three major levels of increasing complexity and importance: awareness,

engagement and control. We also describe the different constituents of each level and their implications for

patient empowerment interventions, focusing on interventions based on information and communication

technologies. Finally, we discuss the implications of this model for the design and evaluation of patient

empowerment interventions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Patient empowerment has emerged as a new

paradigm to improve medical outcomes through

self-directed behavior change. Conceptually,

‘empowerment’ relates to (a) the goal of individuals

to have control over their quality of life, and (b) the

process via which individuals can achieve this goal.

Patient empowerment seems particularly promising

in the management of chronic diseases

(Chatzimarkakis, 2010; Anderson and Funnel, 2010)

and is directly connected with personalized patient

services, education and preventive measures. The

research community accepts that better health

outcomes can be achieved by improving a person's

ability to understand and manage his or her own

health and disease, negotiate with different teams of

health professionals, and navigate the complexities

of health systems (The Lancet, 2012).

Empowerment appears in many different

contexts, always as a cognitive process – that of

enhancing the capacity of individuals or groups to

make choices and to transform those choices into

desired actions and outcomes. For example, human

resource management research recognizes

empowerment as a cognitive process; studies therein

investigate interventions that are designed,

developed and assessed following a cognitive model

of the empowerment process (Robbins et al, 2002;

Thomas and Velthouse, 1990).

In this paper we argue that patient empowerment

should be treated as a cognitive process. We also

propose a cognitive model and we describe its

different constituents and their implications for the

design and evaluation of patient empowerment ICT

(i.e. information and communication technology)

interventions. Finally, we discuss future work to

deploy and validate the proposed model.

2 PATIENT EMPOWERMENT

Julian Rappaport (Rappaport, 1987) defined

empowerment as “a process, a mechanism by which

people, organizations, and communities gain

mastery over their affairs”. Empowerment, in its

most general sense, refers to the ability of humans to

gain understanding and control over personal, social,

economic and political forces in order to take action

to improve their life (Israel et al, 1994). In health

science, patient empowerment is understood as an

enabling process or outcome (Freire, 1993;

McAllister et al, 2012) by which patients are

encouraged to autonomous self-regulation, self-

605

Kaldoudi E. and Makris N..

Patient Empowerment as a Cognitive Process.

DOI: 10.5220/0005281906050610

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health Informatics (HEALTHINF-2015), pages 605-610

ISBN: 978-989-758-068-0

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

management and self-efficacy in order to achieve

maximum health and wellness (Lau, 2002).

Empowerment can therefore be described as a

process where the purpose of an educational

intervention is to increase patients’ ability to think

critically and act autonomously; while it can also be

viewed as an outcome when an enhanced sense of

self-efficacy occurs as a result of the process

(Anderson and Funnell, 2010).

The concept of patient empowerment has

emerged in 1970s in USA and UK as part of the rise

of New Right politics (Traynor, 2003). The concept

eventually evolved as a new paradigm that can help

improve medical outcomes while lowering costs of

treatment by facilitating self-directed behavior

change. The concept seems particularly promising in

the management of chronic diseases

(Chatzimarkakis, 2010; Anderson and Funnel, 2010)

and it is directly connected with personalized patient

services, education and preventive measures. Patient

empowerment has gained even more popularity

since the 1990’s, due to the emergent of eHealth and

its focus on putting the patient in the centre of the

interest. A recent review (Ajoulat et al, 2007) shows

that patient empowerment services mainly aim at

educational programs seeking patient reinforcement.

Indeed, patient education interventions seem to have

taken the lead in the early attempts to strengthen

patients. To illustrate this we have searched PubMed

database for the term ‘patient education’. Figure 1

shows the results (red line), as a plot of number of

papers per year for the last five decades. According

to this graph, published works on “patient

education” first started to appear during the 1960s,

following an increasing curve from the mid-70s until

2006, when their yearly numbers started to decline.

At the same time, research interest begun to focus on

the related concepts of ‘patient engagement’ and

‘patient empowerment’. PubMed searches with these

terms (also plotted in Figure 1, with green and blue

lines respectively) indicate an increasing research

interest, especially during the last decade.

Reviews of the field reveal three basic

dimensions of patient empowerment: education,

engagement, and control (Ouschan et al, 2000,

Unver and Atzori, 2013). Patient education is

perceived as a set of planned educational activities

designed to improve patient health behavior and

health status. Its main purpose is to maintain or to

improve patient health as well as to train the patient

to become able to actively participate in his or her

own healthcare treatment by increasing self-efficacy

(Bandura, 1977). Patient engagement involves two

different concepts: cooperation with health providers

and an active engagement in managing one’s own

health status and disease. The control dimension

refers to the patient’s ability to actively participate in

strategic decisions about his or her health and

disease management.

Although there is a clear distinction between

these three dimensions, often empowerment

interventions include all three dimensions in their

goal and, eventually, in their design. This has

obvious implications for the methodology and tools

that will be used to evaluate the specific

intervention. For example, evaluation of patient

education interventions should examine expected

outcomes such as: understanding health information;

ability to recognize new or warming signs or

symptoms of disease progression and transition; and

self-satisfaction of being well-informed on the

treatment options of his or her condition or disease.

The evaluation of interventions targeting patient

participation should exam different outcomes such

as: the degree of patients’ involvement in treatment

plans; lifestyle and behaviour changes; and the

ability and willingness to share information and

feelings. Finally, evaluation of interventions that

attempt to increase patient control should take into

account outcomes such as confidence in the ability

to make decisions about treatment plans,

maintaining a personal health record, and other

major choices related to health management.

Research so far has revealed interdependencies

between these dimensions. For instance, Roter and

Hall (1992), extensively researched the

communication between doctors and patients and

have noticed that patient education helped patients

gain more control and management of their health,

which in turn encourage patients to ask more

questions and be more active regarding their health

treatment. Moreover, researches revealed that the

maintenance of control by obtaining information

about health statuses, lead to an increased

participation ratio in decision-making regarding

treatment (Makoul et al, 1995). Furthermore,

DiMatteo et al (1994) conclude that patient

education or structural changes to the medical

interaction (i.e. doctor and patient co-authoring

medical records) have led patients to play. more

active roles and develop a greater sense of control of

their health and lives. Despite such findings, current

literature lacks of a tiered, hierarchical approach

towards patient empowerment.

HEALTHINF2015-InternationalConferenceonHealthInformatics

606

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

3500

4000

4500

5000

pubished papers per year

year of publication

patienteducation

patientengagement

patientempowerment

Figure 1: Plot of the PubMed search results for the terms “patient education” (red dashed line), “patient engagement” (green

dotted line), and “patient empowerment” (blue compact line). The results of the 3 searches are plotted as number of

published papers per year for the year range 1960 to 2013.

3 A COGNITIVE APPROACH TO

PATIENT EMPOWERMENT

In its core meaning, empowerment is strongly

related to the control on one’s own action. In this

respect, empowerment could be considered as a

complex construct that involves various cognitive

processes and skills (Falk-Rafael, 2001).

Specifically, some of its basic elements include:

knowledge acquisition, through perception, thinking

and learning, awareness of one’s own current

conditions and /or needs, active participation in the

management of the current or future condition and in

the relevant decision making. (Rappaport, 1984)

Following the overall approach of cognitive

psychology, we propose to treat patient

empowerment in terms of three levels of increasing

complexity and importance: awareness, participation

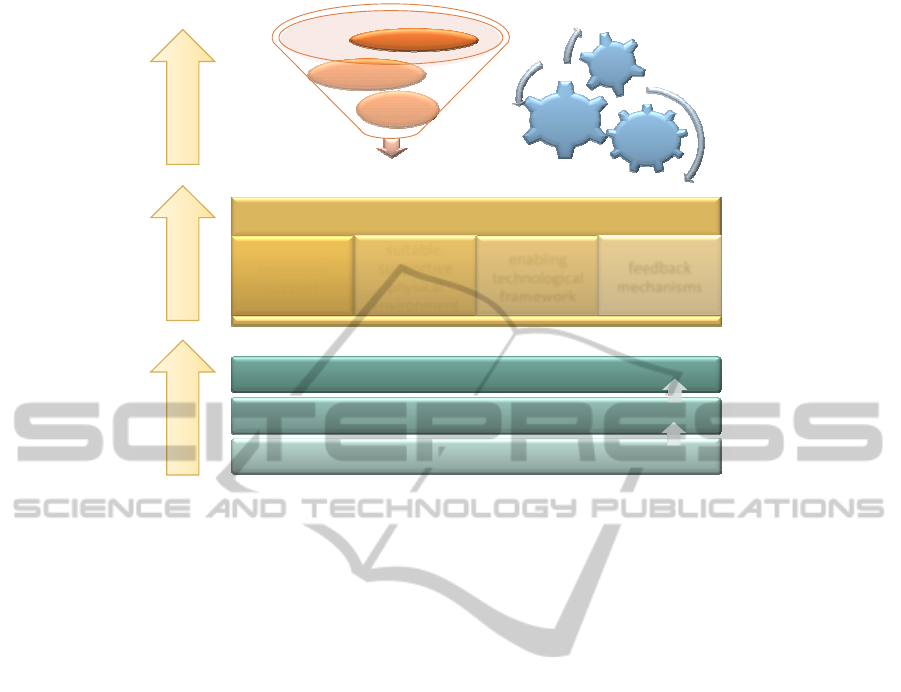

and control (Figure 2).

3.1 Awareness

The first and most basic level refers to the complex

task of health awareness. The patient (or the healthy

citizen in general) should be aware of: his or her

own health status; health related risks and lifestyle

or environment induced hazards; potential disease

progression to more severe stages; potential disease

transition to other comorbidities; measures needed to

stay healthy and/or prevent disease occurrence,

progression or transition.

This level corresponds to the educational

dimension as in current literature. However, we

believe that it is more appropriate to treat it as a

personal awareness of one’s own health rather than

the process of formal education. This underscores

the fact that the patient should clearly understand the

implications of the information provided and is able

to act upon it. In any case, this level on its own can

be viewed as an educational process with three sub-

levels of increasing complexity (Davenport and

Prusak, 2000): information gathering (i.e. simple

facts), knowledge (i.e. information with a purpose),

and understanding (i.e. conscious knowledge and

achievement of explanation). Supporting access to

information is the easiest and most straightforward

task for patient empowerment interventions, be it via

conventional channels of printed material, or via the

nowadays more popular channels based on the

internet and even mobile personal devices

Indeed, today there are many authoritative on-

line databases that provide education material

designed specifically for the patient. One notable

example is the effort of the National Library of

Medicine USA, who provides also the MedLinePlus

(www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/) service for patient

information. Another important example is the

EUPATI network funded by EU. which is a

comprehensive collaborative effort towards

educating the patients so that can take active part in

their treatment and in the research towards new

treatments.

Structuring and organizing information with a

particular educational purpose refers to knowledge.

Managing and supporting this second level of the

PatientEmpowermentasaCognitiveProcess

607

understanding:personalhealthconditionawareness

knowledge:relevant,structuredinformationwithapurpose

information:dataandinformationaggregation

awareness engagement control

action,participation

emotional

support

suitable,

supportive

physical

environment

enabling

technological

framework

feedback

mechanisms

cognitive

emotional

soc

ial

shareddecision

decision

support

collaboration

communication

mindchange

Figure 2: Patient empowerment modelled as a cognitive process. There are three distinct levels of increasing complexity

and importance: awareness, engagement and control. Each level presents its own contributing factors.

educational process is a rather complex issue.

Semantic eHealth interventions can certainly help by

providing relevant semantic medical concept maps

that will allow available medical evidence to be

presented to the patient within context. Also,

advanced visual analytics may offer alternative ways

for patients to grasp difficult medical concepts. The

final step of understanding relates to the patient’s

ability to realize his or her personal condition in

relation to the medical evidence. This actually

means achievement of health awareness. In order to

support this, interventions should follow a combined

approach of coupling medical knowledge to the

personal characteristics of the patient. This

personalization most often will require integration of

personal health data, real-time biomedical sensor

measurements, and data related to lifestyle and

behaviour, beliefs and intentions as harvested via

semantic analysis of unstructured personal data

available in web based social networks.

3.2 Engagement

This second level of patient empowerment strives to

achieve patient engagement in the health care

process. Here we should emphasize active and

proactive participation in managing the disease and

its treatment and in preventing disease progression

and transition. Successful patient participation can

really be achieved only when the patient is health

aware. However, this is not the only prerequisite.

The patient additionally needs emotional strength, a

suitable, supportive physical environment, an

enabling framework and last but not least accurate

feedback in order to be able to re-adjust participation

Emotional strength can generally be reinforced

by easing the communication with health providers

and most importantly within social groups. Both can

be easily supported by common eHealth

interventions that allow an easy and seamless

communication with health providers or provide the

environment for on-line social support groups.

Creating a supportive physical environment may

prove more intriguing. As we cannot easily alter

physical environments to help patients, we could

instead try to alter something equally important: the

perceived environment. Here, future eHealth

interventions should provide the means to identify

resources and opportunities the environment already

provides, which the patient (or its digital assistant)

can exploit to increase the level and quality of

participation in disease management. A simplistic

example would involve an application that

highlights a route within a city suitable for

wheelchairs or places that offer salt free foods.

For the patient to be able to participate

effectively in personal health management a number

of other tools and services often need to be available

– these comprise what we call the enabling

framework. These may include specialized

HEALTHINF2015-InternationalConferenceonHealthInformatics

608

equipment and/or digital interventions that provide

the necessary prerequisites for the patient to be able

to act. Fortunately, nowadays a wealth of such

underline technologies are available, ranging from

personal wearable health sensors to cloud based

personal health applications and dedicated personal

assistants. Finally, active participation requires

improvement of the self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977).

That is, it is necessary for the individual to know her

own abilities and skills or to estimate accurately her

needs for being able to be engaged in action. One of

the most crucial tools for the formation of the self-

efficacy is the accurate feedback, positive or

negative, for individual’s action that is received

from the external environment. Only active

engagement can be meaningful and effective in

fulfilling its aims.

3.3 Control

Control in this context can include two different

aspects: decision making and mind changing.

Decision making refers to a collaborative process

where patient and health professionals discuss and

interact to reach a shared decision. A prerequisite for

this is the patient to be health aware and also

actively involved in her health management. Only

then, the patients’ participation in decision making

should be effective. However, this aspect of control

involves extensive communication and

collaboration. Both are widely supported by current

eHealth applications in a variety of ways, including

also advanced collaboration environments and

shared digital spaces. Some interesting examples

include the emergent technology of personal health

records, owned by the patients themselves, who

however can give targeted access to their health

providers when needed. Also considerable research

work is available in the field of medical decision

support systems, which can be generally viewed as

either (a) the so-called ‘strong’ artificial intelligence

systems whose behaviour is at some level

indistinguishable from humans; or (b) an alternative

approach that looks at human cognition and decides

how it can be supported in complex or difficult

situations, something like a form of ‘cognitive

prosthesis’ that will support the human in a task

(Coreira, 2003). In any case, shared decision support

interventions need to take into account both patients

and health professionals and integrate data and

events from various sources of personal health data

and medical evidence. On the other hand, control of

action involves very internal cognitive processes –

what we refer to as mind changing, that is the

capacity to modify one’s own mental states like

beliefs or intentions . This entails the representation

of causal determinants of lasting behaviour change

from the perspective of the individual, including

perceptions, cognitions, and emotions. Together,

they describe the personal-level motivational

signature of direct goal-seeking behaviour (Piaget,

1976).

This level of empowerment is probably the most

demanding, since it is based on highly

interdisciplinary research which involves

behavioural scientists, psychologists, behaviour

simulation and experiments and finally information

scientists. Attempts to support mind changing need

to take into account individuals' motivations,

attitudes and habits, understand them and then

design an intervention which is aimed at changing

representations first, and then behaviours. Mind

changing is at the basis of human social interactions

because it means that we can identify others' mental

states and act upon them (Conte, 1995). This can be

obtained by several means: communicative actions,

like requests, commands, evaluations, assertions,

etc. and non-communicative actions, which aim to

modify the emotions, feelings, and beliefs of others

without directly stating one’s intentions.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The main point of this research is to justify how the

precise distinction of the three levels of patient

empowerment helps with its application, and help

the patient receive it more smoothly and easily. The

advantages of this process are that we can evaluate

each level separately and not only the final outcome,

identifying possible shortcomings and correcting

them along the way. In other words, the evaluation

and monitoring of patient empowerment have more

clear targets, thus provide new opportunities for

researchers to determinate where and when their

strategy should change. We plan to test the validity

of the model for the evaluation of a novel service

environment for providing personalized

empowerment and shared decision support services

for cardiorenal disease and comorbidities, as part of

the FP7-ICT project CARRE: Personalized Patient

Empowerment and Shared Decision Support for

Cardiorenal Disease and Comorbidities (Grant no.

611140). The project aims to create a set of

empowerment interventions that address all level of

the proposed empowerment model. In particular: (a)

provide visual model of disease comorbidities

trajectories, based on current medical evidence

PatientEmpowermentasaCognitiveProcess

609

(awareness: information aggregation and

knowledge); (b) personalize the risk model based on

his personal medical data and real-time sensors to

support status awareness (awareness:

understanding); (c) use the personalized model in

conjunction with real time monitoring to create a set

of alarms to enable patient engagement

(engagement: enabling framework); and (d) provide

advanced decision support services based on the

real-time coupling of medical evidence, personal

health status and intentions and beliefs, as deduced

from social web data mining (control). The ultimate

goal is to identify available evaluation tools for each

different part of the model and thus provide a

complete framework for the design and evaluation of

patient empowerment interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the FP7-ICT project

CARRE (No. 611140), funded in part by the

European Commission.

REFERENCES

Ajoulat I, d’Hoore W., and Deccache A., 2007. Patient

empowerment in theory and in practice: Polysemy of

Cacophony, Patient Education & Counseling, 66:13-

20.

Anderson R.M., Funnell M.M., 2010. Patient

empowerment: myths and misconceptions. Patient

Educ Couns. 79(3):277-82.

Bandura, A. (1977) Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying

theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review,

84, 191-215.

Chatzimarkakis J., Why patients should be more

empowered, J Diab Science Technol, 4:1570-1573,

2010.

Coreira E., Guide to Health Informatics: 25: Clinical

decision support systems, 2nd Ed., Oxford Univ.

Press, NY, 2003.

Conte R, Castelfranchi C. Cognitive Social Action.

London: UCL Press, 1995.

Davenport, T.H., and Prusak L., 2000. Working

knowledge: how organizations manage what they

know. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

DiMatteo, M. R., Reiter, R. C., & Gambone, J. C., 1994.,

Enhancing Medication Adherence Through

Communication and Informed Collaborative Choice,

Health Communication, 6(4), 253-265.

Falk-Rafael A.R. (2001). Empowerment as a process of

evolving consciousness. A model of empowered

caring. Advances in Nursing Science, 24, 1, 1-6.

Freire P., 1993. Pedagogy of the oppressed., New York:

Continuum.

Israel, B. A. Checkoway, B. Schultz, A. and Zimmerman,

M., 1994. Health Education and Community

Empowerment: Conceptualizing and Measuring

Perceptions of Individual, Organizational and

Community Control. Health Education Quarterly

21(2): 149-170.

Lau D.H., 2002. Patient empowerment – a patient-centred

approach to improve care. Hong Kong Med J. 8 (5):

372-374.

Makoul, G., Arnston, P. & Schofield T., 1995. ‘‘Health

Promotion in Primary Care: Physician-Patient

Communication and Decision Making About

Prescription Medications,’’ Social Science Medicine,

41(9), 1241-1254.

McAllister M, Dunn G, Payne K, Davies L, Todd C.,

2012. Patient empowerment: the need to consider it as

a measurable patient-reported outcome for chronic

conditions. BMC Health Serv Res. 13;12:157.

Ouschan Robyn MMgt, Sweeney Jillian C., Johnson

Lester W., 2000. Dimensions of Patient

Empowerment, Health Marketing Quarterly, 18:1-2,

99-114.

Piaget, G. (1976). The grasp of consciousness. Action and

concept in the young child. Cambridge: Harvard

university press.

Rappaport J., 1987. Terms of empowerment/exemplars of

prevention: Toward a theory for community

psychology. American Journal of Community

Psychology, 15, 121-144.

Rappaport, J. (1984). Studies in empowerment:

Introduction to the issue. Prevention in Human

Services, 3, 1-7.

Robbins T.L, M.D. Crino, L.D. Fredendall, 2002. An

integrative model of the empowerment process.,

Human Resource Management Review, 12, 419–443.

Roter, D. I. and Hall, J. A., 1992. Doctors Talking With

Patients/Patients Talking With Doctors, London,

Auburn House.

The Lancet, 2012. Patient Empowerment – who empowers

whom? The Lancet, 379(9827): 1677.

Thomas K.W., Velthouse B.A., 1990. Cognitive Elements

of Empowerment An “Interpretive” Model of

Instrinsic Task Motivation, Academy of Management

Review, 15:4:666-681.

Traynor M., 2003. A Brief History of Empowerment:

Response to a Discussion with Julianne Cheek.

Primary Health Care Research and Development,

4:129-136.

Unver O., Atzori W., 2013, Deliverable 3.2.

Questionnaire for Patient Empowerment Assessment,

The SUSTAINS FP7 ICT PSP European Commission

project, No. 191905.

HEALTHINF2015-InternationalConferenceonHealthInformatics

610