A Comparative Study on the Impact of Business Model Design &

Lean Startup Approach versus Traditional Business Plan on

Mobile Startups Performance

Antonio Ghezzi, Andrea Cavallaro, Andrea Rangone and Raffaello Balocco

Department of Management, Economics and Industrial Engineering, Politecnico di Milano,

Via Lambruschini 4B, Milan, Italy

Keywords: Digital Business Model, Lean Startup Approach, IT Strategy.

Abstract: Business Model Design (BMD) & Lean Startup (LSA) approach are two widespread practices among

entrepreneurs, where many Mobile startups declare to adopt them. However, neither of the two frameworks

are well rooted in the academic literature; and few studies address the issue of whether they actually

outperform traditional approaches to new Mobile Startups creation. This study’s aim is to assesses the

contribution to performance of the combined use of BMD and LSA for two startups operating in the highly

dynamic Mobile Applications Industry; performances are then compared to those achieved by two Mobile

Star-ups adopting the traditional Business Plan approach. Findings reveal how the combined use of BMD and

LSA outperforms the traditional BP in the cases analyzed, thus constituting a promising methodology to

support Strategic Entrepreneurship.

1 INTRODUCTION

The process an entrepreneur faces in launching a new

venture is characterized by significant complexity

and uncertainty. Such uncertainty is the cause of the

intrinsic high risk that the creation of a new venture

embeds (Eisenmann et al., 2012); (Ries, 2011).

Studies have found that millions of would-be

entrepreneurs participate in new venture creation

every year, although there is large variation in startup

rates among countries (Amorós and Bosma, 2014). At

the same time, the large numbers of startup attempts

are matched by equally large numbers of failed

efforts: for instance, about 75% of U.S. venture-

backed startups fail, according to Harvard Business

School senior lecturer Shikhar Ghosh (Blank, 2013).

Nobel (Nobel, 2011) recently found that, irrespective

of what entrepreneurs define as success, the failure

rate increases as its definition narrows:

whenever failure is considered in terms of asset

winding up, where investors lose part or the whole

investment made, the failure rate is between 30%

and 40%;

assessing failure as a lack of return on

investments, the failure rate is higher and it stands

between 70% and 80%;

finally, if failure reflects the non-achievement of

the targeted goals, the rate increases up to 90/95%.

The reasons behind these poor results are various, and

existing literature (Townsend, 2010) groups them in:

i) a lack of legitimacy; ii) a lack of resources; iii)

entrepreneur human capital; and iv) external factors

such as environment/industry characteristics.

Moreover, insights from the report for Canada’s

National Angel Capital Organization,

“Understanding the Disappearance of Early-stage and

Startup R&D Performing Firms”, tells much about

the gloomy picture surrounding early-stage startups,

show that the key factors attributed for the demise of

these companies were: no revenue from customers,

no input from customers on R&D performed or on the

product or service being developed, misreading of

markets, product not needed or not simple enough for

the application, poor sales and marketing decisions,

wrong timing, and unaware of competitors and

changing market conditions (Barber and Crelinsten,

2009). Notwithstanding the long list of mistakes that

determine poor performance and high Startup

mortality, the reported problems appear to

fundamentally point at a paramount issue:

entrepreneurial practices followed by entrepreneurs

196

Ghezzi A., Cavallaro A., Rangone A. and Balocco R..

A Comparative Study on the Impact of Business Model Design & Lean Startup Approach versus Traditional Business Plan on Mobile Startups

Performance.

DOI: 10.5220/0005337501960203

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2015), pages 196-203

ISBN: 978-989-758-098-7

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

are often unlinked with traditional strategic theory

and practices. Indeed, entrepreneurs tend to craft their

endeavors around an original business idea, and fully

devote their effort in pursuing its operational

concretization without a clear strategic orientation

(Kisfalvi, 2002); in addition to this, they tend not to

take stock of existing strategy analysis models, which

are seldom employed in the early phases of the new

venture activity (Ghezzi, 2013). Hence, strategy is

mistakenly perceived as an obscure tool by many

“startuppers”, and as a result, the relationship

between the original business idea, the new venture’s

goals, the actions to achieve such goals, and the

related performance, is often lost in translation (Kraus

and Kauranen, 2009). The research stream on

Strategic Entrepreneurship aims at tackling this issue

from an essentially theoretical standpoint, in the

attempt to supply entrepreneurs with top-down,

formal and sound tools to approach strategy.

Recently, however new bottom-up and rather

practitioner-oriented approaches emerged to

tentatively fill this shortcoming: in this study, we

focus on two approaches which are still under

investigated, due to their embryonic stage of

development (Trimi and Berbegal-Mirabent, 2012)

and their fuzzy definition (Zott et al., 2011), i.e. the

Business Model Design (BMD) and the Lean Startup

approach (LSA). The business model concept has

generally referred to “architecture of a business”

(Timmers, 1998) where the essence was defining how

the enterprise delivers value to customers, enticing

them to pay and converting the payments to profit

(Teece, 2010). The Lean Startup Approach has

achieved large consensus among practitioners, where

many startups declared to adopt this approach. The

term, coined by Eric Ries (Ries, 2011) refers to a

business approach that aims to change the way that

companies are built and new products are launched.

In this study, we propose to investigate the potential

contribution of BMD and LSA to strategic

entrepreneurship’s theory and practice. We first open

our work by arguing that these two practical

approaches show inherent relationships with the

legacy of both Strategic Management and

Entrepreneurship literature streams, and could be

positioned at the crossroad of the two: hence, we craft

a framework to organize and frame these emerging

approaches used in launching new ventures within the

strategic entrepreneurship literature stream – i.e., the

intersection between the entrepreneurship and

strategy streams – (e.g. Hitt, 2001). Such further

investigation is also in line with Audretsch et al.,

(2010) who state that several literature gaps exist in

the field of entrepreneurship and, as specifically

concerns new frontiers in entrepreneurship, an issue

(out of seven issues proposed) interesting to

investigate refers to the “mechanism underlying

processes of learning and innovation within and by

new ventures”. Second, at an empirical level, our

study aims at comparing the effectiveness of the

emerging BMD and LSA approaches with that of the

traditional Business Plan approach to support new

Information and Communication Technology (ICT)

ventures creation. By presenting and discussing four

longitudinal cases of startups development in the

Mobile industry, the performances achieved by two

startups created combining the emerging approaches

of BMD and LSA are benchmarked with the

performances of the two other new firms initially

developed adopting the traditional Business Plan

(BP) approach. An action research setting enabled

direct experience on the four cases, and the findings

allow to underscore the impact of the design approach

undertaken on achieved performance. Indeed, an

improved understanding of the approaches used by

entrepreneurs in creating new firms is critical to

explaining the survival and growth of new ventures.

The ultimate purpose of our work is hence to frame

BMD and LSA in the broader Strategic

Entrepreneurship field, and provide ICT

entrepreneurs with evidences that such combined

approaches may outperform the traditional BP and

make for improved performance.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

2.1 Business Model Design

Research on BM design evolved from elaborating

taxonomies (e.g. Rappa, 2001), to defining a theory

(Osterwalder, 2004), to supporting firms’ strategy

analysis (Ghezzi, 2012). When analyzing BMs, the

researchers’ focus has shifted from a single firm to a

network of firms, gradually transforming the BM

from a monolithic entity to a multifaceted concept

(Ballon, 2008), to be investigated as a combination of

multiple and diverse design dimensions and

interrelations. Such multifaceted evolutionary

process, though beneficial to establish BM design as

a research stream, burdened the theory with a lack of

homogeneity (Johnson et al., 2008). In fact, several –

often heterogeneous – frameworks or templates have

been proposed to construct maps of BMs, to clarify

the processes underlying, and then to allow

considering alternative combinations of these

processes (also called building blocks or parameters).

While the impact of business models and their

AComparativeStudyontheImpactofBusinessModelDesign&LeanStartupApproachversusTraditionalBusinessPlan

onMobileStartupsPerformance

197

innovation on a firm’s success appears to be

convincing (Cortimiglia et al., 2015), till now the

construct has been only very poorly understood

(Teece, 2010). Scholars, in fact, are still concerned

with the theoretical foundation and definition of BM

and the literature is developing largely in silos,

according to the phenomena of interest of the

respective researchers (Ghezzi, 2014). Nevertheless,

the framework proposed by Osterwalder and Pigneur

(2010) – the business model canvas - is now widely

adopted and employed by practitioners, and identifies

nine parameters to decompose a business model: (i)

value proposition; (ii) customer segments; (iii)

channels; (iv) customer interface; (v) key activities;

(vi) key resources; (vii) key partners; (viii) revenue

model; (ix) cost structure.

Although BMD design within the

entrepreneurship field is a recent topic, it is gaining a

growing attention in the literature (Trimi and

Berbegal-Mirabent, 2012; Ghezzi et al., 2013; Ghezzi

et al., 2015a). Performance of entrepreneurial firms is

strongly conditioned by their adopted business

models (Zott and Amit, 2007). However, new

ventures in rapidly changing environments change

their business models several times to succeed (Ries,

2011). Thus, business model design and change is

especially critical to new technology-based firms

(Andries and Debackere, 2007). Resulting from this

fuzzy environment, many startups fail, and a large

number of those that survive end up being acquired

by larger companies. In addition to adopting business

models to facilitate technological innovation and the

management of technology, firms can view the

business model itself as a subject of innovation

(

Mitchell and Coles, 2003). One of the main

developments in business model design regards the

business model canvas: such framework is widely

adopted and employed both by practitioners

(Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010) and academics (e.g.,

see Chesbrough, 2010).

2.2 Lean Startup Approach

The LSA introduces two new concepts: minimum

viable products (MVP) that efficiently test business

model hypotheses, and pivots that change certain

business model elements in response to failed

hypotheses tests. As a third element, unlike other

methods for managing early stage venture, the lean

startup approach balances the strong direction that

comes from a founder’s vision with the need for

redirection that follows from market feedback

(Eisenmann et al., 2012).

One of the main differences between existing

companies and startups lies in the business model

issue: while existing firms execute a business model,

startups look for one (Blank, 2013). Such distinction

is at the heart of the lean startup approach. When

following this approach, an entrepreneur translates

her/his vision into falsifiable business model

hypotheses, and then tests those hypotheses using a

series of minimum viable products (MVPs). Each

MVP represents the smallest set of activities needed

to disprove a hypothesis (Eisenmann et al., 2012);

(Ries, 2011); (Blank, 2013).

Based on test feedback, an entrepreneur must

decide whether to persevere with her proposed

business model; pivot to a revised model that changes

some model elements while retaining others; or

simply perish, abandoning the new venture. He or she

repeats this process until all of the key business model

hypotheses have been validated through MVP tests.

A hypothesis-driven approach helps reduce the

biggest risk facing entrepreneurs: offering a product

that no one wants. Many startups fail because their

founders waste resources building and marketing

products before they have resolved business model

uncertainty. By bounding uncertainty before scaling,

the hypothesis-driven approach optimizes use of a

startup’s scarce resources (Eisenmann et al., 2012);

(Blank, 2013).

2.3 Business Plan

Kraus and Kauranen (Kraus and Kauranen, 2009)

state that business plan (BP) plays an important

linking role between entreprenership and strategic

management. The BP is the document which

describes the enterprise’s strategy, i.e. content and

process, thereby presenting the vision of the

enterprise and how the enterprise is going to attain its

vision (Honig and Karlsson, 2004). In particular, the

BP can serve as the basis of the strategy itself and as

its formalized documentation. The business plan

typically includes a set of key documents, organized

around the following sections (Abrams and Abrams,

2003):

general description of the firm;

general description of products/services;

strategic plan;

marketing plan;

operating plan;

human resources and organization plan;

financial plan, and economic and financial

projections.

Several strategic tools and models have been

traditionally used to craft the BP The main ones are

the Abell’s model for the competitive positioning

(reference) and the SWOT (Strength-Weakness-

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

198

Opportunity-Threat) analysis to generate strategic

alternatives. There is still no agreement in literature

about the usefulness of business planning and

empirical findings have been fragmented and

contradictory (Brinckmann et al., 2010); some

scholars (i.e. (Bhide, 2000)) argue that planning

interferes with the efforts of firm founders to

undertake more valuable firm. Notwithstanding such

theoretical disagreement, the business plan is the

document typically used by investors to evaluate

funding opportunities

(Burke et al., 2010).

3 METHODOLOGY

Since the thin archival record deposited by many

startups requires entrepreneurship researchers to “get

their hands dirty”, many entrepreneurship researchers

– even those without relevant prior experience – may

gain an understanding of practical issues through

direct research involvement in new ventures. Thus,

startups provide a useful laboratory for studying

many of the research questions central to strategy and

organization (Ireland and Webb, 2007). Taking

advantage of the authors’ direct experience within

two different masters courses offered in an EQUIS-

accredited School of Management, a selection of four

cases of Startups in the Mobile industry was made,

and these cases have been analyzed in-depth, in the

attempt to identify the difference from theory to

practice, and from what the companies claim they do

and what they actually do. The opportunity for cases

identification came from the involvement in two

master courses: an executive master in business

administration, whose target students is represented

by managers of large companies, which lasted two

years and it was held in 2011 and 2012; and a newly

designed master directly addressing new

entrepreneurs: the first edition of the course has been

launched in 2012. In the first, we took the role of

tutors responsible for leading participants in the

adoption of the traditional BP approach to assess

either strategic investments in well-established ICT

environments or original business ideas to start a new

venture. In the second course, we were tutors in a

newly designed master directly addressing new

entrepreneurs: the master was more open to new

approaches, as the business model canvas and the lean

startup approach were the heart of the teaching

activity, requiring startuppers

to develop their startups following these approaches.

The cases analyzed were selected according to the

following filters: (i) the case had to be related to an

actual startup, i.e. a new ventures launched before or

during the course; (ii) the case had to be focused on

the Mobile Industry; and (iii) the entrepreneurs had to

be willing to be led by the tutors in the actual strategic

process, openly sharing data and information. The

Mobile Industry was selected due to its

pervasiveness, global relevance, suitability to test

both the BP and the BMD-LSA approaches, and

market-specific expertise from the authors.

As a result, four cases were selected, where two

of them applied the traditional BP and two applied the

BMD-LSA. The target firms were all Mobile startups

focusing on mobile applications that were in the

launching phase: this is in line with the research

objectives and, according to Venkataraman (1997),

the level of analysis is constituted by new enterprise

itself. This allowed us to compare the results of the

analysis. Therefore we had the opportunity to study

and compare two different approaches used by new

ventures in their very early stage of life in the

dynamic context of the Mobile Industry. Table 1

reports the key data from the new ventures analyzed.

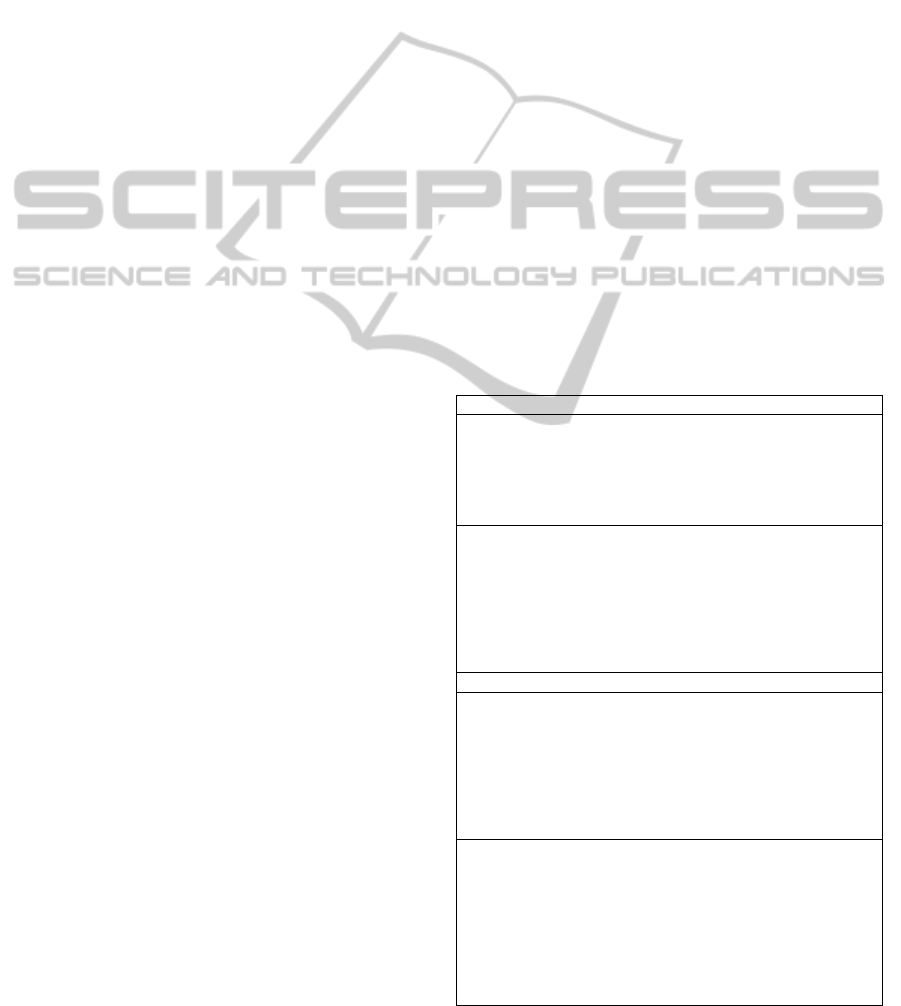

Table 1: The 4 Mobile startups analysed.

BMD+LSAAPPROACH

Startup:AppyU

MarketSegment:Couponing

Description:Appthatallowsfindingoffersanddiscountsinbarsand

cafeterias of Milan.Theuser has onlytodownloadtheapp on his

ownsmartphonetoobtaincouponswithdiscountsupto40%onthe

priceofbreakfasts,lunches,happyhoursordrinks.

Startup:Pinevent

MarketSegment:EventManagement

Description:Mobile App thatallows userstolook forand visualize

ICTBusinesseventsinItalyontheirownsmartphone(morethan500

workshops and conferences). It is possible to search for events

through keywords, sectors, geographic area, etc). Once the user

selectsanevent,

hecanseeallthedetails,shareitonsocialnetworks

andinsertitintheagenda.

BPAPPROACH

Startup:CallATaxi

MarketSegment:Transport

Description:MobileApp that allowstocalla taxidirectlyfrom the

smartphone,inaneasyandfastway.Oncethetaxihasbeencalled

the user can see the right position of the taxi and can know the

estimatedwaitingtime.Whentheuserreachthefinaldestinationhe

can pay with the smartphone, evaluates the taxi driver and lets a

commentaboutthetravel.

Startup:CryptoLAB

MarketSegment:Security(Counterfeiting)

Description: An anti‐counterfeiting service that enables

manufacturers to reduce the phenomenon of counterfeiting and

gray market for their products; it also allows the consumer to

independentlyverifytheauthenticityofaproductpriortopurchase.

Theverificationisperformedbyusingasmartphoneandcanbedone

either at the store or on the web. It is a computer system service

combinedwithaspecifictypeofproductlabels.

AComparativeStudyontheImpactofBusinessModelDesign&LeanStartupApproachversusTraditionalBusinessPlan

onMobileStartupsPerformance

199

Because of the authors’ direct role in the

development of these startups, our research activity

conforms to the tenets of action research (AR).

Avison et al., (1999) define action research as an

iterative process involving researchers and

practitioners acting together on a particular cycle of

activities, including problem diagnosis, action

intervention, and reflective learning. AR is perhaps

the most widely discussed collaborative research

approach, and a significant amount of literature on

this topic is currently available (e.g. see Baskerville

and Wood-Harper, 1998).

Cuervo et al., (2007) hold that researchers who

want to make a unique and worthwhile contribution

to entrepreneurship research should seriously

consider making the effort to study new enterprise

efforts, although collecting this kind of data is far

from easy. New enterprise efforts would be studied

over time regardless of their organizational context

and their human champion both of which may change

over time.

4 EMPIRICAL RESULT

As seen throughout the literature review, there is a

broad spectrum of performance measures around

which new ventures are compared and evaluated.

Nonetheless, measuring the performance of new

ventures is problematic because there is no consensus

among researchers as to what constitutes

entrepreneurial success (Brush and Vanderwerf,

1992). Moreover, prior studies point out that

entrepreneurs have differing objectives for starting

new firms (e.g., “lifestyle ventures” versus

“gazelles”) and that objectives may vary in

importance at different stages in the entrepreneurial

process and in different industries. According to

Kakati (2003) most of the new venture researches

have focused on financial indexes, for instance by

taking ROI as a measure of new venture performance,

despite the pitfalls of using ROI (i.e. the firms would

not be expected to achieve break-even within the first

few years and ROI is sensitive to accounting

practices). Other researches focus also on market

share gain - but Miller et al. (1998) hold that this

measure may be problematic for pioneering ventures,

as they would initially have 100% of the market, only

to have this reduced as new firms entered - sales

growth and so on and so forth, mainly because of

being readily available, easy to measure and non-

confidential. Therefore, we tried to build a “vector of

performance” considering some of the parameters

presented in literature that are key in the startup

development process. We consider our approach to

measuring performance a viable – though possibly

imperfect – solution one to a very complex problem.

In sum, our set of performance measures is composed

by:

1. termination of the new venture (TNV);

2. product development (PD);

3. venture organization activity (VOA);

4. equity funding (EF);

5. first customer acquisition (FCA).

Shane and Delmar (2004) define termination of the

organizing effort as a decision to terminate the

endeavor made by all members of the venture team,

because venture teams are often quite fluid, leading a

venture to proceed with only part of the group that

initiated the effort. We decided to focus on TNV

because, as suggested by Shane and Delmar (2004),

continuation of the organizing effort is a necessary

condition for all other activities in new ventures. A

new venture can achieve no other performance goal

(achievement of first sale, positive profits, or the

acquisition of financing) if it has been terminated.

Our involvement as tutors in the startups’ team

allowed us to know immediately whether everyone

pursuing the venture has terminated, and if so, when.

We also took into account two other different

aspects of new venture development used by Delmar

and Shane (2003): PD, which they define as the

creation of the product or service that the venture will

sell; and VOA, which they define as the set of

activities to establish the organization that will

provide the new product or service. We measured

product development as the amount of time needed to

develop the first product or service delivered to the

market, while we measured venture organizing as the

time needed to set up those activities that establish the

physical structure and organizational processes of a

new firm (Bhave, 2004). The last variable takes into

account whether the startup has accomplished all the

different activities related to bureaucracy (e.g.

registration with government and tax authorities, the

obtainment of permits and licenses to operate) and to

both logistic and marketing issues (e.g. purchasing of

raw materials, equipment, facilities and marketing

and promotion activities). Then we also took into

account whether the startup has received financing

from any venture capital firm or not. The credibility

associated with a funding event gives a strong signal

about the quality of the startup. In a market with high

uncertainty, the relevance of this signal is likely to be

significant in reducing the perceived uncertainty of

being associated with a particular company (Davila et

al., 2003). Finally, we also monitored the time passed

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

200

from the launch of first version of the product to the

first customer/external user acquired. We added this

variable because in the LSA customer feedback

constitutes a relevant part of the methodology.

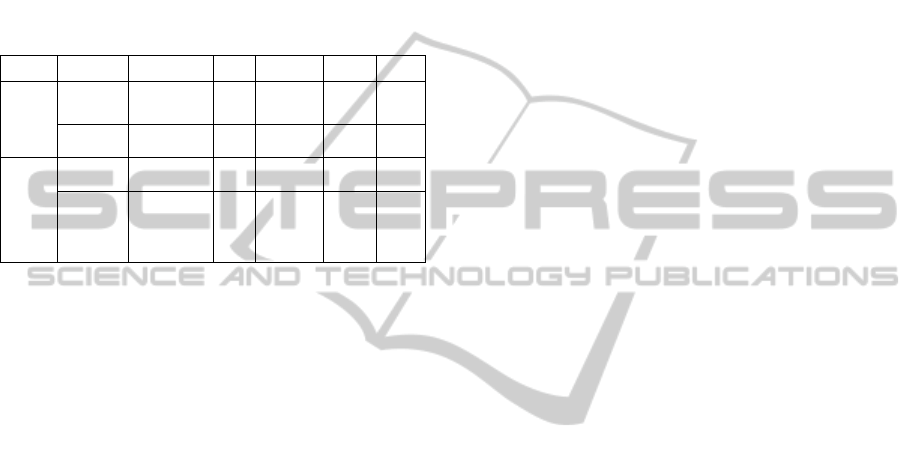

Table 2 summarizes the different startups’

performances. The findings show how all the

performances achieved by startups following a BMD

+ LSA approach were superior than those achieved

(or not achieved) by those startups developed through

a BP.

Table 2: The comparative analysis of the 4 startups.

Approach Startup VOA TNV PD FCA EF

BMD

+

LSA

AppyU

3,5months

(completed)

No 3months 2weeks

Yes

(Seed)

Pinevent

2,5months

(completed)

No 4months 1week

Yes

(Seed)

BP

CallATaxi

9months

(completed)

No 8months

2

months

Yes

(Seed)

CryptoLAB

1,5year(not

yetcompleted)

No

1,5year

(notyet

completed)

No No

Apart from the performance comparison, during

the action research some other issues arose. During

the whole LSA it emerged that some resources and

competencies neglected by the entrepreneurial team

were, instead, “core resources” (meaning that they are

important in sustaining the competitive advantage of

the firm) (Gezzi et al., 2015b). Nonetheless, we also

noticed that the LSA fastened the “learning process”

of founders, pushing them in improving/acquiring

competencies and capabilities that are core in running

the new Business Model.

5 CONCLUSION

This paper provides two main contributions to the

existing knowledge. On the one hand, this study

frames in the academic literature two well-known

popular tools among practitioners: the Business

Model and the Lean Startup Approach. Our

theoretical framework show that BMD and LSA

should be included in the strategic entrepreneurship

literature field, since their founding elements are

linked with the strategic literature and the

entrepreneurship literature too. These findings

represent the first step to provide a robust theorization

of the two emerging concepts, to lay the basis for

rigorous empirical validation. Our study offers an

alternative approach to strategically drive the process

of entrepreneurial action, and supports the idea that

exists an “entrepreneurial method” analogous to the

scientific method (Sarasvathy and Venkataraman,

2011). Furthermore, the main theoretical contribution

of the BMD and the LSA to existing theories of

entrepreneurial action like Effectuation and

Bricolage, is to highlight the importance of

experimentation and to stress the learning aspect of

the entrepreneur during the journey of starting a

company. The need for a shift from simple business

planning to experimentation and learning has been

recently put forward by some studies (Brinckmann et

al., 2010), and this paper provides practical evidences

supporting this point of view. On the other hand, this

paper provides also some practical implications. The

main contribution lies in guiding practitioners

towards new approaches – appropriately rooted in the

theory - favoring the shift from the traditional

approach based on Business Planning, by now

obsolete in the turbulent ICT context, to the new

approach constituted by a combination of BMD and

LSA. In fact, Bhide (Bhide, 2000) argues that the

efficacy of written business plans is context specific:

it is likely to have a positive impact in more static and

predictable/stable markets but less so in more

uncertain markets where entrepreneurs are

introducing highly innovative products/services.

Moreover, the analysis we made makes us suggests

that in order to develop a new venture BMD and LSA

should come first; BP could be used as a second step,

to refine the previous methods’ outcome and better

frame the business idea in the competitive landscape.

This is particularly true in high turbulent environment

as in the Mobile industry. Hence, the ideal process

that starts with the business idea generation should

then continue with the design of a business model and

the application of the lean techniques. When the

business idea reaches the product/market fit, the new

entrepreneur could write the BP, and employ those

traditional strategic models she or he too often tend to

disregard. This study is not without limitations, which

mainly derive from any potential observer bias in the

action research activities: this is a shortcoming that

burdens qualitative research, though the rigorous

methodology employed (e.g. we followed all the 5

principles proposed by Davison et al., 2004) in order

to conduct a rigorous action research activity)

attenuates this limitation. Moreover, other limitations

refer to the need to generalize findings drawn from a

single industry, to the small sample size of startups

analyzed and to the selection of key performance to

evaluate. To conclude, our research outlines several

opportunities for future research; first, it pushes to

further investigate and enhance the theoretical roots

of BMD and, above all, LSA, so as to further justify

their positioning in the strategic entrepreneurship

AComparativeStudyontheImpactofBusinessModelDesign&LeanStartupApproachversusTraditionalBusinessPlan

onMobileStartupsPerformance

201

research stream. Secondly, future research efforts

could try to better understand the efficacy of BMD e

LSA in launching new ventures, and to investigate

how all the relationships between the BMD and LSA

change during the very early stage of life of the

Startups. Moreover, we pave the way to the

investigation of whether the simultaneous application

of the LSA and BMD in the early stage of a new firm

can help entrepreneurs in the exploration of new

opportunities. Other future research avenues should

try to overcome all this study’s limitations by

validating findings in different contexts and

analyzing larger samples for instance. Finally,

according to Kraus and Kauranen (Kraus and

Kauranen, 2009), one of the most promising areas for

future research is the pre-startup planning stage.

Strategic management of an enterprise before and

during the phase of its foundation is a topic of

increasing interest. This includes research on the role

of the business plan in the planning process, another

topic of growing academic interest.

REFERENCES

Abrams, R., & Abrams, R. M. (2003). The successful

business plan: secrets & strategies. The Planning Shop.

Amorós, J. E., & Bosma, N. (2014) Global

Entrepreneurship Monitor, Global Report.

Andries, P., & Debackere, K. (2007). Adaptation and

performance in new businesses: Understanding the

moderating effects of independence and industry. Small

Business Economics, 29(1-2), 81-99.

Audretsch, D., Dagnino, G., Faraci, R., & Hoskisson, R.

(2010). New frontiers in entrepreneurship. Springer.

Avison, D. E., Lau, F., Myers, M. D., & Nielsen, P. A.

(1999). Action research. Communications of the ACM,

42(1), 94-97.

Ballon, P. (2007). Business modelling revisited: the

configuration of control and value. info, 9(5), 6-19.

Barber, H., & Crelinsten, J. (2009). Understanding the

Disappearance of Early-stage and Startup R&D

Performing Firms. The Impact Group, Toronto,

septembre.

Baskerville, R., & Wood-Harper, A. (1998). Diversity in

information systems action research methods.

European Journal of Information Systems, 7(2), 90-

107.

Bhave, M. P. (1994). A process model of entrepreneurial

venture creation.Journal of business venturing, 9(3),

223-242.

Bhide, A. (2000). The origin and evolution of new

businesses. Oxford University Press.

Blank, S. (2013). Why the lean startup changes everything.

Harvard Business Review, 91(5), 63-72.

Brinckmann, J., Grichnik, D., & Kapsa, D. (2010). Should

entrepreneurs plan or just storm the castle? A meta-

analysis on contextual factors impacting the business

planning–performance relationship in small firms.

Journal of Business Venturing, 25(1), 24-40.

Brush, C., & Vanderwerf, P. (1992). A comparison of

methods and sources for obtaining estimates of new

venture performance. Journal of Business venturing,

7(2), 157-170.

Burke, A., Fraser, S., & Greene, F. J. (2010). The multiple

effects of business planning on new venture

performance. Journal of management studies, 47(3),

391-415.

Chesbrough, H. (2010). Business model innovation:

opportunities and barriers. Long range planning, 43(2),

354-363.

Cortimiglia, Ghezzi, A., M., Frank, A. (2015). Business

Model Innovation and strategy making nexus:

evidences from a cross-industry mixed methods study.

R&D Management, DOI: 10.1111/radm.12113.

Cuervo, A., Ribeiro, D., & Roig, S. (2007).

Entrepreneurship: Concepts, theory and perspective.

Springer.

Davila, A., Foster, G., & Gupta, M. (2003). Venture capital

financing and the growth of startup firms. Journal of

business venturing, 18(6), 689-708.

Davison, R., Martinsons, M. G., & Kock, N. (2004).

Principles of canonical action research. Information

systems journal, 14(1), 65-86.

Delmar, F., & Shane, S. (2003). Does business planning

facilitate the development of new ventures?. Strategic

Management Journal, 24(12), 1165-1185.

Eisenmann, T., Ries, E., & Dillard, S. (2012). Hypothesis-

Driven Entrepreneurship: The Lean Startup. Harvard

Business School Entrepreneurial Management Case,

(812-095).

Ghezzi A. (2013). Revisiting Business Strategy Under

Discontinuity. Management Decision, 51 (7), 1326-

1358.

Ghezzi A. (2014). The dark side of the Business Model. The

risks of strategizing through business models alone.

Strategic Direction, Vol. 30, Issue 6, 1-4.

Ghezzi A., Balocco R., Rangone A. (2013). Technology

diffusion theory revisited: a Regulation, Environment,

Strategy, Technology model for technology activation

analysis of Mobile ICT. Technology Analysis &

Strategic Management, 25(10), 1223-1249.

Ghezzi, A. (2012), “Emerging Business Models and

Strategies for Mobile Platforms Providers: a Reference

Framework”, Info, Vol. 14 No. 5, pp 36-56.

Ghezzi, A., Balocco, R., Rangone, A. (2015b). A fuzzy

framework assessing corporate resources management

for the mobile content industry. Technological

Forecasting and Social Change

doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2015.01.004.

Ghezzi, A., Cortimiglia, M., Frank, A. (2015a). Strategy

and business model design in dynamic

Telecommunications industries: a study on Italian

Mobile Network Operators. Technological Forecasting

and Social Change, 90, Part A, 346-354.

Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., Camp, S. M., & Sexton, D. L.

(2001). Strategic entrepreneurship: entrepreneurial

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

202

strategies for wealth creation. Strategic management

journal, 22(6-7), 479-491.

Honig, B., & Karlsson, T. (2004). Institutional forces and

the written business plan. Journal of Management,

30(1), 29-48.

Ireland, D. R., & Webb, J. W. (2007). Strategic

entrepreneurship: Creating competitive advantage

through streams of innovation. Business Horizons,

50(1), 49-59.

Johnson, M. W., Christensen, C. M., & Kagermann, H.

(2008) Reinventing your business model. Harvard

business review, 86(12), 57-68.

Kakati, M. (2003). Success criteria in high-tech new

ventures. Technovation, 23(5), 447-457.

Kisfalvi, V. (2002). The entrepreneur's character, life

issues, and strategy making: a field study. Journal of

Business Venturing, 17(5), 489-518.

Kraus, S., & Kauranen, I. (2009). Strategic management

and entrepreneurship: friends or foes. International

Journal of Business Science and Applied Management,

4(1), 37-50.

Loch, C. H., Solt, M. E., & Bailey, E. M. (2008).

Diagnosing unforeseeable uncertainty in a new

venture*. Journal of product innovation

management, 25(1), 28-46.

Miller, A., Wilson, B., & Adams, M. (1988). Financial

performance patterns of new corporate ventures: an

alternative to traditional measures. Journal of Business

Venturing, 3(4), 287-300.

Mitchell, D., & Coles, C. (2003). The ultimate competitive

advantage of continuing business model

innovation. Journal of Business Strategy, 24(5), 15-21.

Nobel, C. (2011). Why Companies Fail and How. Harvard

Business School Business Knowledge.

Osterwalder, A. & Pigneur Y. (2010) Business Model

Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game

Changers, and Challengers, John Wiley & Sons,

Hoboken, NJ.

Osterwalder, A. (2004), “The Business Model Ontology. A

proposition in a design science approach”, PhD thesis,

École des Hautes Études Commerciales de l’Université

de Lausanne.

Rappa, M. (2001), Business Models on the Web: Managing

the digital enterprise, State University, North Carolina.

Ries, E. (2011). The lean startup: How today's

entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create

radically successful businesses. Random House LLC.

Sarasvathy, S. D., & Venkataraman, S. (2011).

Entrepreneurship as method: Open questions for an

entrepreneurial future. Entrepreneurship Theory and

Practice, 35(1), 113-135.

Shane, S., & Delmar, F. (2004). Planning for the market:

business planning before marketing and the

continuation of organizing efforts. Journal of Business

Venturing, 19(6), 767-785.

Teece, D.J. (2010), “Business Models, Business Strategy

and Innovation”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 43, No. 2-

3, pp. 172-194.

Timmers, P. (1998). Business models for electronic

markets. Electronic markets, 8(2), 3-8.

Townsend, D. M., Busenitz, L.W., & Arthurs, J. D. (2010).

To start or not to start: Outcome and ability

expectations in the decision to start a new venture.

Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 192-202.

Trimi, S., & Berbegal-Mirabent, J. (2012). Business model

innovation in entrepreneurship. International

Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 8(4), 449-

465.

Venkataraman, S. (1997). The distinctive domain of

entrepreneurship research: An editor’s perspective.

Advances in entrepreneurship, firm emergence, and

growth, 3, 119-138.

Zott, C., & Amit, R. (2007). Business model design and the

performance of entrepreneurial firms. Organization

Science, 18(2), 181-199.

Zott, C., Amit, R., & Massa, L. (2011). The business model:

recent developments and future research. Journal of

management, 37(4), 1019-1042.

AComparativeStudyontheImpactofBusinessModelDesign&LeanStartupApproachversusTraditionalBusinessPlan

onMobileStartupsPerformance

203