Digital Curation Costs

A Risk Management Approach Supported by the Business Model Canvas

Diogo Proença

1,2

, Ahmad Nadali

1,2

, Raquel Bairrão

1,2

and José Borbinha

1,2

1

Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

2

INESC-ID, Lisbon, Portugal

Keywords: Data Curation, Digital Preservation, Business Model Canvas, Risk Management.

Abstract: Data management has been emerging as a specific concern, which when applied through the full lifecycle of

the data also has been named of data curation. However, when it comes to the estimation of costs for digital

curation the references are rare. To address that problem we propose a method a pragmatic method based on

the body of knowledge of risk assessment and the established concept of Business Model Canvas. The

details of the method are presented, as also references to a tool to support it, and the demonstration is

provided by its application to a real case (a national Web Archive).

1 INTRODUCTION

Data is being increasingly perceived by

organizations as an asset and not only as simply a

resource required to support processes. Therefore,

data management has been emerging as a specific

concern, which when applied through the full

lifecycle of the data also has been named of data

curation. Within a data lifecycle, comprising from its

initial creation to final deletion, we also can find

processes to add value to that data, reassess it (as for

example, for compliance concerns), reuse it, etc., we

also realize an emerging concern with data

preservation.

The concepts of digital curation, and within it of

digital preservation, also have been used in the

domain of scientific data, where it is perceive that it

“involves maintaining, preserving and adding value

to digital research data throughout its lifecycle. The

active management of research data reduces threats

to their long-term research value and mitigates the

risk of digital obsolescence.” (DCC, 2014)

The main purpose of data preservation is to

ensure that data is reliably retrievable for use

anytime it is required. For the management and

engineering of data preservation several references

have been developed, namely the OAIS - Open

Archival Information System reference model

(CCSDS, 2012), which defines the concept of a

repository to support the digital preservation of

digital assets.

However, when it comes to the estimation of

costs for digital curation in general, and preservation

in particular, the references are rare. This is the

problem we therefore are addressing here.

Existing work already proposed an approach to

the analysis of digital preservation as a risk

management problem (Barateiro, 2010). Following

that, we decided to explore the potential of the Risk

Management (RM) concepts to advance in the

techniques to estimate costs of digital curation. In

fact, from this RM perspective we propose that costs

are what we have to give up for controls, which in

turn are the measures that we have to put in practice

to minimise loss or to maximise gain. In that sense, a

control is anything we are considering applying to

either minimise negative impacts or to take

advantage of opportunities to produce value and thus

bring gains. However, we must also agree that, in

most of the usual digital curation scenarios, it is

usually very difficult to estimate the absolute value

of an asset. For that reason, for now we ignored the

measurement of value, and focused only in the

identification of controls as the source of costs.

However, we also are aware that RM is a

complex area of expertise, requiring a complex and

usually expensive infrastructure of people and other

resources in order to be effective.

In order to address the expressed vision and also

the exposed limitations, our proposed makes use of

two tools: a risk registry and a BMC - Business

Model Canvas (Osterwalder, 2009).

299

Proença D., Nadali A., Bairrão R. and Borbinha J..

Digital Curation Costs - A Risk Management Approach Supported by the Business Model Canvas.

DOI: 10.5220/0005398502990306

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2015), pages 299-306

ISBN: 978-989-758-098-7

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

A BMC requires organisations to conceive their

business model of nine blocks structured in a visual

canvas, which allows for easy understanding of their

business. This can help to understand both what can

positively affect the value propositions of the

business (opportunities) and what can negatively

affect those same value propositions (risks).

The idea behind our proposal is therefore to

understand an OAIS repository as a business in itself

(either autonomously, or as a service provided in the

scope of an organization), and identify and

understand the risks and their impact on each of the

nine building blocks of its BMC. We demonstrate

how the BMC technique can be used to find risks

and then controls for those risks. This in turn makes

it possible to estimate the related costs as part of the

overall costs of curation.

In conclusion, our contributions here proposed

for the digital curation problem are:

A pragmatic method for risk assessment, based

on the main references from the risk

management domain;

A generic BMC for the business of an OAIS

repository: This BMC can serve as template for

organizations where digital curation has an

important role, which can make local instances

of it;

A generic risk registry for scenarios of OAIS

repositories, created after analysing

DRAMBORA (DCC/DPE, 2007) and

comprising.

This generic BMC, with an associated generic

registry of risk questions and common related

controls, can be very relevant for the domain of

digital curation and for cost evaluation within that.

For validation, this pragmatic method was

applied to a real case study: a data archive in a

national web archive.

This paper is structured as followed. Section 2

provides an overview of the risk management

domain, and Section 3 describes the concept of

Business Model Canvas. Section 4 details the

method used to identify risks based on a BMC of an

organization. Section 5 presents the generic BMC

for digital preservation that can be instantiated to a

specific organization. Then, Section 6 depicts a

snippet of the risks and controls registry. Section 7

and presents a case study demonstrating the

application of the method. The paper is then

finalized by presenting the conclusions and future

work.

2 RISK MANAGEMENT

The main references on Risk Management from the

International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO)

are:

ISO Guide 73: Vocabulary for risk management

(ISO, 2009);

ISO 31000: Risk management principles and

guidelines (ISO/FDIS, 2009a);

ISO 31004: Risk management—Guidance for the

implementation of ISO 31000 (ISO/TR, 2013);

IEC 31010: Risk assessment techniques

(ISO/FDIS, 2009b).

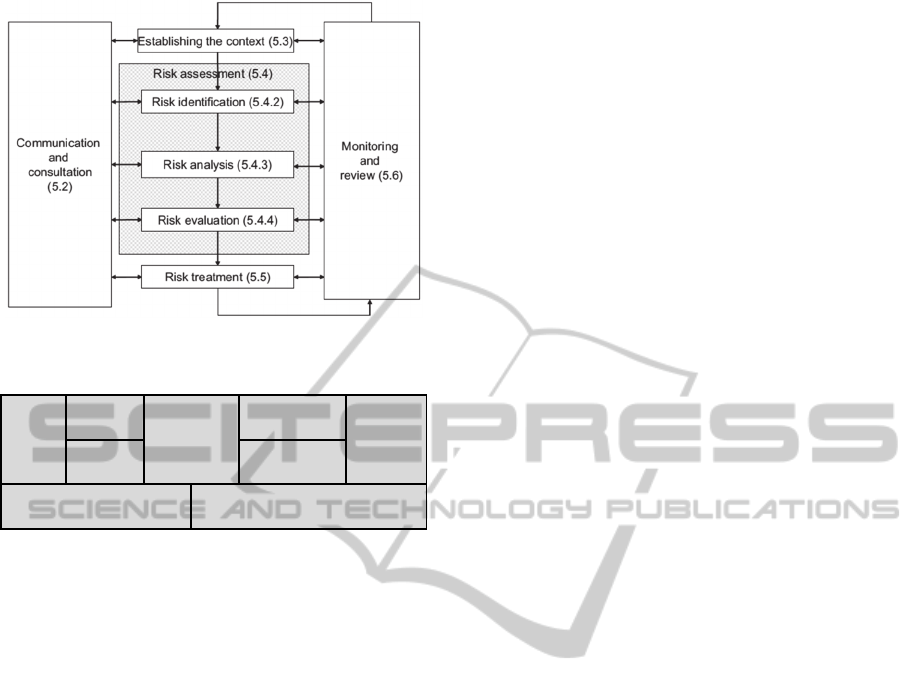

According to those sources, organisations should

define internal RM processes taking as a starting

point the generic method proposed in ISO 31000

(ISO/FDIS, 2009a) (illustrated in Figure 1). For the

assessment activities of those processes, IEC 31010

(ISO/FDIS, 2009b) provides a catalogue of

potentially relevant techniques.

From ISO 31004 we learn that:

“The effect that this uncertainty has on the

organisation’s objectives is risk. (…) The

understanding that risk can have positive or negative

consequences is a central and vital concept to be

understood by management. Risk can expose the

organisation to either an opportunity, a threat or

both. (…) Controls are measures implemented by

organisations to modify risk that enable the

achievement of objectives. Controls can modify risk

by changing any source of uncertainty (e.g. by

making it more or less likely that something will

occur) or by changing the range of possible

consequences and where they may occur.” (ISO/TR,

2013).

So, even if we are not following a specific RM

method as part of the governance framework of a

repository, we cannot avoid having to deal with the

identification of risks and controls. However, as a

complete RM methodology can be complex and

expensive to implement, we are here proposing a

simplified method that can be used at least for a

preliminary phase of costs estimation. If, after the

application of this method, the stakeholders of a

repository feel the RM principles are valuable for

the governance of their case, and it is worthy to

consider a proper and full RM method, then at least

these preliminary results can be reused for that

purpose.

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

300

Figure 1: The Risk Management Process according to the

ISO/FDIS 31000.

Key

Partners

Key

Activities

Value

Propositions

Customer

Relationships

Customer

Segment

Key

Resources

Channels

Cost

Structure

Revenue

Streams

Figure 2: The generic structure of a Business Model

Canvas.

3 BUSINESS MODEL CANVAS

The Business Model Canvas “allow a group of

people to fill it in through brainstorming sessions

and thus create a relevant understanding of their

business model”. (Osterwalder, 2009)

For that it makes use of nine building blocks,

illustrated in the Figure 2 (Osterwalder, 2009).

In a valuable canvas each block must have at

least one shared assumption about the business. A

group can even develop more than one BMC in

order to represent alternative understandings or just

different views of the same business.

After its initial proposal in (Osterwalder, 2004),

other authors developed or adopted the canvas

approach for other purposes, such as for example the

Lean canvas (LeanStack, 2014). In the meantime it

has been suggested that doing a BMC exercise is

already in some sense performing a risk assessment

(Parrisius, 2013) (McAfee, 2013). Other authors

have gone even further and proposed the hypothesis

that the BMC concept can even be extended to

support a pragmatic risk analysis (Schliemann,

2013). The motivation behind it is to understand

both what can positively affect the value

propositions of the business (opportunities) and what

can negatively affect those same value propositions

(risks).

The idea is to identify and understand the risks

and their impact (positive and negative) on each of

the nine building blocks of the BMC, as well as the

risk appetite of the stakeholders upon which a

business depends, such as regulators and investors.

There is a large body of knowledge from the risk

management community on how to assess and

measure risk through analytical tools, but this new

technique fills the need to introduce risk assessment

at a higher level, scoping it visually in consideration

for each of the building blocks of the BMC.

When applying this technique to identify the

risks and their impact there should be a series of

risk-related questions for each of the nine building

blocks of BMC. Simple examples of these questions

are proposed in the original business model risk

canvas, but for real use these should be scoped for

the business in question.

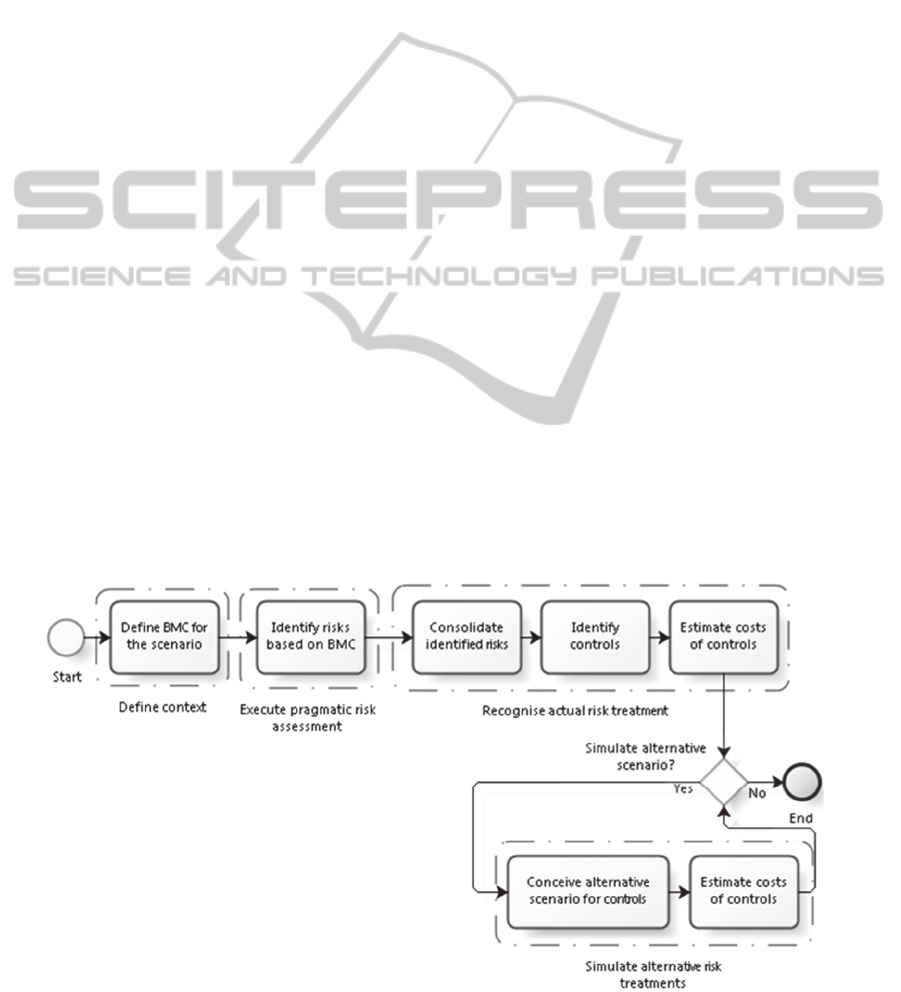

4 A METHOD TO IDENTIFY

RISKS BASED ON A BMC

It was inspired by the previous sources on RM and

BMC that we decided to explore the hypothesis of

developing and demonstrate a method to estimate

costs of digital curation. We believe such a method

can be useful in two possible scenarios:

“Current” scenarios, where the costs of controls

already exist in the repository as a means to

reduce the impact of a consequence of a risk,

change the likelihood of an event, or reduce the

exposure to a vulnerability;

“Future” scenarios, where the costs of controls

do not yet exist, but where repository managers

are able to consider alternative scenarios of

repository governance.

The foundations of this method draw from relevant

sources, such as the ISO 31000 and the BMC. The

core stages of the method are:

1. Define the Context: Define the requirements of

the main elements of the organisation (mission,

etc.); the assets (data and services), and the

external stakeholders and, based on that, define

the BMC for the scenario.

2. Execute a Pragmatic Risk Assessment: Use a risk

repository, or consult experts, in order to identify

relevant risks associated with the BMC.

3. Recognise Actual Risk Treatment (to apply in an

analysis of a “Current” scenario):

DigitalCurationCosts-ARiskManagementApproachSupportedbytheBusinessModelCanvas

301

Consolidate the risks identified (mainly, to

detect repetitions and overlaps). This is the

best step to also identify potential positive

impacts (if that also is a purpose).

Use internal information, and (if necessary)

also consult a risk repository or experts, to

identify the controls to apply for the

consolidated risks.

Estimate the costs for these controls (the ideal

is to calculate these costs precisely, however,

best estimates can also be useful).

4. Simulate Alternative Risk Treatments (an

optional activity, to be executed as many times

as needed, to explore possible alternative

“Future” scenarios):

Use internal information, eventually also can

be consulted a risk repository or experts, and

according to the businesses strategic view

and governance rules, conceive alternative

scenarios for controls of the identified risks.

This is the best step to explore opportunities

to exploit positive impacts (if that also is a

purpose).

Estimate the costs for these controls (make

the best estimate for the costs of this new

scenario).

The process is illustrated in the Figure 3 (diagram

expressed in BPMN, the Business Process

Modelling Notation language).

5 A GENERIC BMC FOR

DIGITAL ARCHIVES

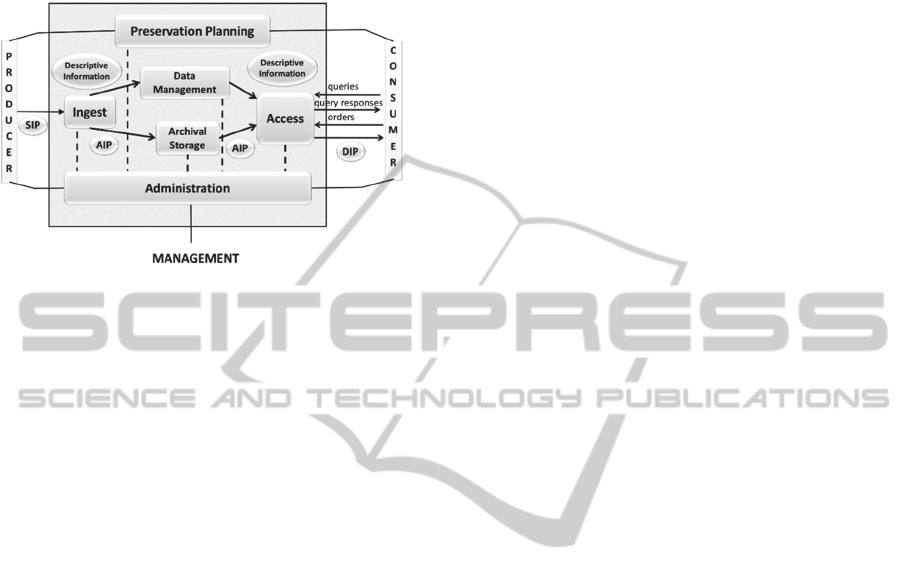

A key reference for digital repositories as systems

conceived to support digital preservation is the

OAIS Open Archival Information System reference

model (CCSDS, 2012).

We therefore used it as our main reference to

develop the generic BMC for that domain. The

purpose of this generic BMC is to serve as a

reference template that can be instantiated to specific

organizations running an archive as part of their

business.

An OAIS is “an Archive, consisting of an

organization, which may be part of a larger

organization, of people and systems, that has

accepted the responsibility to preserve information

and make it available for a Designated Community.

It meets a set of responsibilities that allows an OAIS

Archive to be distinguished from other uses of the

term ‘Archive’. The term ‘Open’ in OAIS is used to

imply that this Recommendation and future related

Recommendations and standards are developed in

open forums, and it does not imply that access to the

Archive is unrestricted.” (CCSDS, 2012) This same

source proposes a reference architecture for this

concepts, as shown in the Figure 4. The document

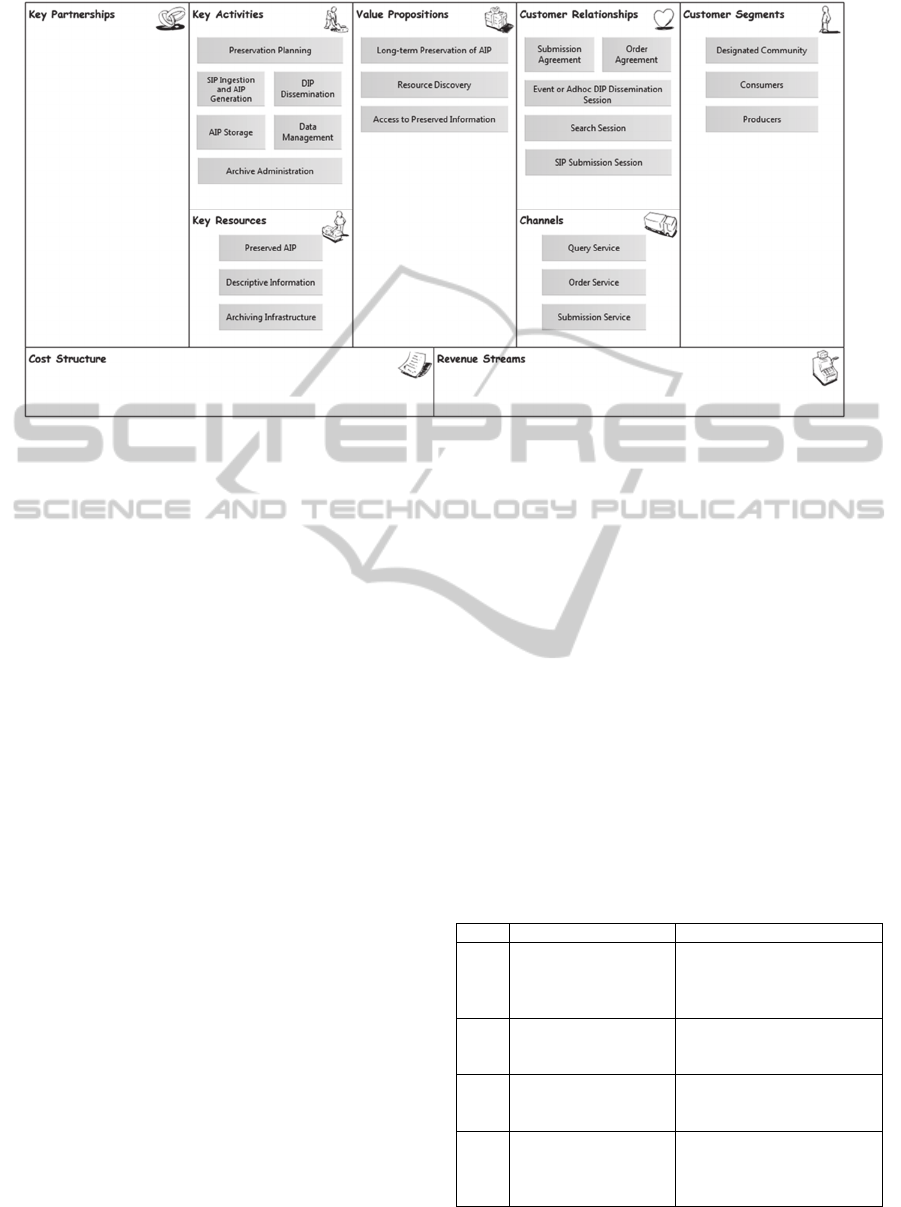

was analysed and as a first step the Value

Propositions were identified. The value propositions

building block “describes the bundle of products and

services that create value for a specific Customer

Segment” (Osterwalder, 2009)

Looking at the OAIS functional entities (depicted

in Figure 4) it can identified the customers of an

Figure 3: BPMN diagram of the pragmatic method to estimate costs of curation focusing on risks and controls.

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

302

archive as being the Producers and Consumers.

There is also another type of customer named the

designated community which is a potential

consumer.

Figure 4: OAIS Functional Entities (CCSDS, 2012).

The points of contact between the archive and

the customers are the functional entities Ingest and

Access. In Access there are two types of interactions

identified as queries and orders. These were

identified for Ingest as “Long-term preservation of

AIP”, which is the value that producers take out of

the archive. For the consumers interactions it were

identified two value propositions, one for the queries

depicted as “Resource Discovery” in the BMC and

one for orders which is identified as “Access to

Preserved Information” in the BMC.

From these value propositions the channels were

identified, the channels building block “describes

how a company communicates with and reaches its

customer segments to deliver a value proposition”.

(Osterwalder, 2009) In order to deliver the three

value propositions identified earlier there is the need

to create the appropriate channels as such it was

identified one channel for each of the value

propositions. In order to enable long-term

preservation of AIPs for Producers there is the need

to have a “Submission Service” to ingest data into

the archive for long-term preservation. Two enable

the resource discovery value proposition a query

service is needed to allow consumers to search for

holdings of interest in the archive. And finally to

access the preserved information there needs to be

an order service which allows consumers the retrieve

the identified holdings of interest from the archive.

The next step was to identify the customer

relationships which are described as “the types of

relationships a company establishes with specific

customer segments”. (Osterwalder, 2009) To engage

with Producers and ingest content the archive needs

to establish a “Submission Agreement” which

describes the data model of the information to be

ingested in the form of a Submission Information

Package (SIP), besides this the archive must also

allow a “SIP Submission Session” that allow

Producers to submit SIPs for ingest into the archive.

For resource discovery the relationship between the

archive and consumers is established using a

“Search Session” in which consumers perform

queries on the archive holdings. Finally, consumers

engage in an “Event or Adhoc DIP Dissemination

Session” to retrieve holdings of interest in the form

of a DIP which is created according to an “Order

Agreement” which has been agreed upon by both the

archive and Consumers.

The key resources describe “the most important

assets required to make a business model work”.

(Osterwalder, 2009) In order to allow for long-term

preservation of an AIP there is the need to have an

“Archiving Infrastructure” which supports the

ingesting of an AIP and also the preserved objects

described as “Preserved AIP” in the BMC. To allow

resource discovery of holdings in the archive the

“Archiving Infrastructure” is also needed to support

the execution of queries and the “Descriptive

Information” to allow consumers to find the relevant

holdings. Finally, to allow the access to the

preserved information the “Archiving Infrastructure”

is needed to support the generation of a DIP from an

AIP according to the Order Agreement. To finalize

the rationale behind the creation of this generic

BMC the key activities are identified. Key activities

describe “the most important things a company must

do to make its business model work”. (Osterwalder,

2009) If we look again to the functional entities of

an OAIS (Figure 4) the key activities are the

functional entities from OAIS. In order to allow for

long-term preservation of AIPs, the archive must

perform “SIP Ingestion and AIP generation” which

is the Ingest Functional Entity, it must also perform

“Preservation Planning”, “AIP Storage” which is the

Archival Storage Functional Entity and must

perform “Archive Administration” which is the

Administration Functional Entity. To allow resource

discovery the archive must perform “Data

Management” which allows access to descriptive

information necessary to identify relevant holdings

in the archive. Finally, for the archive to allow

access to preserved information it must perform

“DIP Dissemination” which is the Access Functional

Entity and must also have “Archive Administration”.

Regarding the Key Partnerships, Cost Structure

and Revenue Streams these could not be properly

identified from OAIS and according to our vision

these are context dependent. For example, an archive

can have software providers as key partners if the

DigitalCurationCosts-ARiskManagementApproachSupportedbytheBusinessModelCanvas

303

Figure 5: The generic BMC for OAIS.

software is developed outside of the archive.

However, there are archives that have in-site

development. The cost structure also changes

depending on the legislation of the archive and

established accounting laws. The revenue streams

are also context dependent, one archive might have

its main source of revenue from public funding if it

is a public organization, it might also provide

training which makes for another revenue stream. As

such, these building blocks are empty in the generic

OAIS BMC and are filled in the instantiations using

real cases. The generic BMC is presented in Figure

5.

Due to space restrictions, all the details of the

generic BMC cannot be presented here; therefore,

for the detailed descriptions and more information

please visit http://4ctoolset.sysresearch.org/.

The BMC presented in Section 7 is an

instantiation of the generic BMC based on OAIS

presented in section 5. For some of the objects in the

canvas there are specific case-dependent

instantiations of the object between square brackets.

For example, if there is an object with Producers

[Researchers] this means that for that specific case

the producers are researchers. There are also objects

there were not present in the generic OAIS BMC

and are specific for the case depicted in that BMC.

6 A REFERENCE RISKS AND

CONTROLS REPOSITORY

One other artefact that was realized to be important

to support the proposed method is a reference risk

repository for the domain digital curation. A risk

repository established concept in risk management,

meaning any kid of system used to store and

managed the knowledge required to support a risk

assessment process.

For that purpose, generic risks and controls were

identified after analysing the main reference in the

domain for this purpose, the DRAMBORA - Digital

Repository Audit Method Based on Risk

Assessment (DCC/DPE, 2007). DRAMBORA

results from an effort to conceive criteria, means and

methodologies for risk assessment of digital

repositories. A sample of the result of that analysis is

presented in Table 1. The detailed registry of risks

and controls can be found at

http://4ctoolset.sysresearch.org/.

Table 1: Generic risks and controls identification.

Id Generic Risks Generic Controls

R1

Business fails to

preserve essential

characteristics of

digital assets

Define main characteristics

of digital content for

information preservation

R2

Business policies and

procedures are

inefficient

Document and make

available business policies

and procedures

R3

Enforced cessation of

repository operations

Plan for continuation of

preservation activities

beyond repository's lifetime

R4

Activity allocates

insufficient resources

Use mechanisms to measure

activity efficiency in terms

of allocated resources,

procedures and policies

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

304

Table 1: Generic risks and controls identification (cont.).

Id Generic Risks Generic Controls

R5

Community

requirements change

substantially

Identify, monitor and review

the understanding of the

community requirements

and of the repository

objectives

R6

Community feedback

not received

Use mechanisms (e.g. email,

surveys) for soliciting

feedback from repository

users community

R7

Community feedback

not acted upon

Define policies to

acknowledge community's

feedback

R8

Loss of key

member(s) of staff

Appoint a sufficient number

of appropriately qualified

personnel

R9

Personnel suffer skill

loss

Implement mechanisms to

identify ongoing personnel

training requirements

R10 Budgetary reduction

Define a financial

preservation plan to assure

self-sustainability of

repository

R11

Software failure or

incompatibility

Install software updates

R12

Hardware failure or

incompatibility

Monitor hardware

performance

R13

Obsolescence of

hardware or software

Maintain hardware/software

up to date to meet repository

objectives

R14

Media degradation or

obsolescence

Allocate resources to

monitor media storage

lifetime and assess potential

value of emerging

technologies

R15

Local destructive or

disruptive

environmental

phenomenon

Implement physical security

measures (e.g. video-record)

R16

Non availability of

core utilities (e.g.

electricity, gas)

Define internal means to

nullify disruption of service,

monitor and review contract

agreements of provider's

services

R17

Loss of other third-

party services

Document and review

service level contracts or

service commitments with

utility provider

R18

Loss of

authenticity/integrity

of information

Monitor, record and validate

integrity of received content

7 CASE STUDY: A NATIONAL

WEB ARCHIVE

This National Web Archive preserves the

information published on the web of clear interest

for the community for future access. It also provides

research resources, for instance, in the fields of

History, Sociology or Linguistics and preserves

information from the past that is no longer available

on the Internet. With the creation of a system that

supports regular crawls of the national web, its long

term storage and access, it is intended to provide the

following services: Term search over the archived

contents; URL search over the archived contents;

New search engine over the national web; Historical

collections of web contents for research purposes;

Characterization reports of the national web; Backup

system of the archived information; Archived data

parallel processing system.

As a complement, the National Web Archive

also strives to achieve the following goals: Train

human resources in web archiving to enable the

maintenance of the system in the future; Export

know-how, experience and technology in web

archiving to other countries; Contribute to increase

the number of domains registered under the national

domain; Publish scientific and technical papers that

enable the sharing of the acquired. The instatiation

of the BMC for this case study can be found at

http://4ctoolset.sysresearch.org/.

The risks were identified through the analysis of

the BMC for the case study and identified by their Id

from Table 1. Regarding the controls for the risks

identified, refer to Table 1. For a more detailed

analysis of the risks and controls for both the case

study visit the Holirisk tool in

http://4ctoolset.sysresearch.org/ in the page of the

BMC for this case study.

Revenue Streams - Risks related to the worth of a

repository business and the value it offers to the

community: R10.

Cost Structure - Risks regarding the cost to support

the repository business: R8; R13; R16; R18.

Channels - Risks related to the communication and

dissemination of the business provided by a

repository: R6.

Customer Segments - Risk that relates with what

the repository should deliver within the community

vision: R5.

Customer Relationships - Risks associated with the

community that makes use of the repository for their

research work: R7.

Key Resources - Risks related to the resources of

infrastructure and personnel which sustain the

repository business: R15; R3; R8; R9; R11; R12.

Value Propositions - Risks regarding the vision and

value of a repository: R1; R2.

Key Partnerships - Selected risks regarding the

outsourcing services repository may depend on to

deliver the preservation business: R13; R17.

DigitalCurationCosts-ARiskManagementApproachSupportedbytheBusinessModelCanvas

305

Using Table 1 and the detailed risks and controls

from http://4ctoolset.sysresearch.org/ as well as the

list of consolidated risks we can identify potential

controls for the identified risks.

8 CONCLUSIONS

This paper proposed a pragmatic method for

identifying risks from a Business Model Canvas

which is based in two different scenarios, (1)

“Current” scenario, where the controls already exist

in the repository as a means to reduce the impact of

a consequence of a risk and; (2) “Future” scenario,

where the controls do not yet exist, but where

repository managers are able to consider alternative

scenarios of repository governance.

The foundations of this method make use of

relevant sources of literature, such as the ISO 31000

and the Business Model Canvas. The focus of this

paper was to present the method as a pragmatic

technique, and provide some example for a case

study. This paper also provided two tools to

accomplish the goals of the method proposed: (1) A

generic BMC, which can be used as a template for

organizations to instantiate to their specific context

and (2) A risk registry for digital curation: a registry

of risks derived, and also common related controls,

relevant for the domain of digital curation.

The work on this paper was developed with the

aim of being simple and easily applicable to every

organization that has digital curation as part of its

core competencies, and proved to be effective in

identifying risk and controls relevant for an

organization based on the analysis of a BMC.

As future work, this whole method can be

implemented in a software system that deals with

risk management. As of now there is already a risk

management software named Holirisk (available

from http://4ctoolset.sysresearch.org/) that will

support the method described in this paper. Our

assumption is that this method will be relevant for

further organizations that want to gain knowledge of

the risks they face without the burden of a “full” risk

management approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by national funds through

Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) with

reference UID/CEC/50021/2013, and by the project

4C, co-funded by the European Commission under

the 7th Framework Programme for research and

technological development and demonstration

activities (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement

no. 600471.

REFERENCES

J. Barateiro, G Antunes, F. Freitas, J Borbinha, 2010.

Designing digital preservation solutions: A risk

management-based approach. International Journal of

Digital Curation 5 (1), 4-17

CCSDS, 2012. Space data and information transfer

systems – Open archival information system –

Reference model – Magenta Book - CCSDS 650.0-M-

2.

DCC, 2014. What is digital curation? [Online]. Available

from: http://www.dcc.ac.uk/digital-curation/what-

digital-curation

DCC/DPE, 2007. DCC and DPE Digital Repository Audit

Method Based on Risk Assessment, version 1.0.

ISO/FDIS, 2009a. ISO 31000: Risk Management—

Principles and guidelines.

IEC/FDIS, 2009b. ISO 31010: Risk management—Risk

assessment techniques.

ISO, 2009. ISO Guide 73: Risk management—Vocabulary.

ISO/TR, 2013. ISO 31004: Risk management—Guidance

for the implementation of ISO 31000.

LeanStack, 2014. Lean Canvas—1 Page Business Model.

[Online]. Available from: http://leanstack.com/

McAfee, S., 2013. Why Do For-Profits Get All The Best

Resources?! 2 Tools Every Nonprofit Can Use to

Manage Risk. [Online]. Available from:

chttp://www.leanimpact.org/nonprofit-program-

development-risk-management-tools/

Parrisius J., 2013. Business Modeling to Reduce Risk.

[Online]. Available from: http://juliusparrisius.

wordpress.com/2013/03/25/business-modeling-to-

reduce-risk/

Osterwalder, A., 2009. Business Model Generation,

Alexander Osterwalder & Yves Pigneur.

Osterwalder A., 2004. The Business Model Ontology—A

Proposition in a Design Science Approach, University

of Lausanne.

Schliemann, M., 2013. BMI? Of course, but what about

the Model Risks? [Online]. Available from:

http://beyondeconomics.es/bmi-of-course-but-what-

about-the-model-risks/

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

306