Connecting Peer Reviews with Students’ Motivation

Onboarding, Motivation and Blended Learning

Kay Berkling

Cooperative State University Baden-Württemberg, Karlsruhe, Germany

Keywords: Blended Learning, Problem based Learning, Software Engineering, Education, Ecosystem of Learning,

Self-directed Learning, Gamification, Scaffolding, Self-directed Learning.

Abstract: This paper evaluates the onboarding phase for students who are exposed to a blended and open learning

environment for the first time, where self-directed learning is key to success. The study was undertaken in a

very restricted environment, where the primary motivation of students is the achievement of good grades in

the most efficient manner due to extreme time constraints. In past research, we have shown that students

have difficulty to move from the traditional setting of frontal lecture and final exam to an open learning

environment that focuses more on self-directed learning and peer created content than grades. This work

builds on findings that blended learning environment should be adaptive to learner types and gamification

features need to be implicit. Adaptivity is not guaranteed through a single platform but instead by involving

students in constructing their learning environment. This paper reports on the final set up of the course and

the student evaluation thereof. We show that the current environment with student involvement leads to

mostly positive attitudes towards most aspects of the course across virtually all students. Forums are

perceived as a barrier as are individual contributions to the class content and are not appropriate features for

onboarding. In contrast and despite being difficult, effective use of peer reviews can be shown to match

student motivation across all learners. Their use is understood as a means to obtaining a good grade and

learning.

1 INTRODUCTION

This paper is the fifth in a series of publications

about the results of gamifying a course in Software

Engineering. The gamified version of the course,

builds on mastery and autonomy. Both are different

from traditional classrooms, where a single exam

results in a grade and not necessarily mastery of the

subject and teacher driven content often does not

leave too much room for autonomy. A course that

insists on mastery of the material (repeated hand-ins

until perfection) and self-driven learning is difficult

because firstly, it is so different from anything

previously seen in teaching and secondly, the rate of

learning appears to slow down even while enhancing

long-term retention (Björk, 2013; p.421). The first

experience with a gamified version of the course

resulted in a lack of acceptance by students and

exposed the mismatch with student motivators,

geared solely towards grade and efficient learning to

the test due to time constraints. Explicit gamification

was perceived as inappropriate for the serious

business of study in this culture (Berkling and

Thomas, 2013). The need for an adaptive

environment geared towards different learner types

and scaffolding during “onboarding” was also

shown in previous work (Thomas, Ch., 2013). Not

only are autonomy and mastery difficult for

students, but they are difficult to implement for a

single teacher with around 100 students. It would

mean giving feedback to homework on a weekly

basis. To afford this feedback loop, peer reviews are

introduced into the classroom.

Peer reviews have become popular as a method

of grading in large scale settings of MOOCS.

According to Piech et al. who have studied Coursera

MOOCs in detail, aspects of peer review (incentive,

presenting complex scores back to students,

assigning reviewers) are still open research problems

(Piech, 2013). Studies look at how accurately the

peer grade reflects the expert teacher grade in order

to justify peer review as student grade. Some studies

show the difficulty that peer reviews pose to

students from the feeling of power to not

understanding their use. According to one study,

professionalism is lacking, loyalty to fellow students

24

Berkling K..

Connecting Peer Reviews with Students’ Motivation - Onboarding, Motivation and Blended Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0005410200240033

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 24-33

ISBN: 978-989-758-108-3

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

interferes and inadequate effort is apparent because

it is not required (Nilson, 2002). In line with these

findings, in a previous version of this course, peer

reviews have been shown to be a difficult

component and were simply neglected by students.

As a result, they were not appreciated for their

potential usefulness.

Platform adaptation and scaffolding through

extrinsic motivation changed this. (In this paper,

adaptation relates to the fact that students choose

their own environment. There are currently no

system-based adaptive learning platforms available

to us.) Feedback was made public on platforms that

are chosen and controlled by students. The

importance of modern social platforms in

communication and learning reflects studies by

several researchers (Herbert 2010, Aydin 2012,

Timaz 2012, Prizo 2011). The completion of peer

reviews is recorded and figures directly into the final

grade, thereby creating an immediate incentive as a

scaffolding device. With these changes, autonomy

through defining their own environment and project

and mastery through reworking homework based on

peer feedback now show a clear and immediate

connection to the final grade. While small changes

and tweaks will always remain, the basic framework

of the onboarding process is finalized as presented in

this paper. We report on a student survey regarding

their perception of this learning environment. 81

participants took part in this survey, taken from three

different classrooms of 27, 23, and 31 students each.

The purpose of this survey is to determine the

student contentment with their learning environment

given the new circumstances. The expectation is to

find that with this change, diverse learner types feel

comfortable with the course. The second motivation

for the survey was to better understand the

onboarding process. It is important that the students

do not perceive the learning environment as

threatening, which has been shown to happen in our

non-scaffolded setups. In this work we show that

peer reviews are difficult but accessible with

scaffolding and modern social platforms. After the

first rounds of difficulty, students understand the

impact that peer reviews have on their motivation of

obtaining a good grade. The use of other elements

(such as Forum, e-Portfolio) of the blended course

have been less successful without the necessary

scaffolding.

The paper is structured as follows. After a review

of the theoretical and historic foundations for this

work in Section 2, Section 3 will describe the course

setup. Section 4 will explain the design of the

survey. Section 5 will discuss results that describe

students’ perception of the components that make up

the course. Section 6 offers conclusion and future

work.

2 BACKGROUND FOUNDATION

The software engineering course is designed to take

gamification into account in an implicit manner, due

to the local culture, where explicit gamification may

not match the seriousness of the situation of

studying (Berkling and Zundel, 2013). There are

implicit elements to the course that are motivated by

gamification and the underlying motivational theory

of Pink’s universal motivators: Mastery, Autonomy

and Relatedness or Purpose (Pink, 2010). In

particular the vocabulary from gaming is used to

think of the first semester as onboarding process

designed as player journey (Kim, 2010), also

emphasized in J.Tagg’s work on scaffolding (Tagg,

2003). In the language of gaming, Points, Badges

and Levels are comparable to the traditional form of

grading students. A slow transition to intrinsic

motivation akin to mastery and autonomy is

accomplished by weaning students off the “cheap”

scaffolding reward system, leading towards learning

as the key accomplishment. (see also Self-

determination theory Ryan Deci (Ryan, 2000;

Gagné, 2005)). While the course uses gamification

principles, the vocabulary is not used during

teaching due to cultural aspects (Berkling, 2013).

In that sense, we are also looking at students as

gamers according to the classification of (Bartle,

1996). Learner types play a role as we have seen in

the past (Berkling and Thomas, 2014) but to assess a

student’s learner type is too difficult in a simple

survey and students are not able to directly and

accurately classify themselves as participant,

avoidant, independent, dependent, collaborative or

competitive (Riechmann, 1974). We therefore use a

simplified model to classify the students according

to gamer type (by asking students to sorting game

examples according to how likely they are to enjoy

them) and personality traits: collaborative,

competitive, creative and open to new experiences.

This gives us a two-dimensional very rough

classification of students’ players and learner types.

As predicted when technology is aligned with

motivation and content (Derntl, 2005), student

perception of the course is currently mostly positive

for scaffolded components after understanding and

aligning student motivation with content and

platform - despite the novelty of the setup.

ConnectingPeerReviewswithStudents'Motivation-Onboarding,MotivationandBlendedLearning

25

3 COURSE SETUP

The Software Engineering course is setup to be

taught across several cohorts of student groups of

about 30. Students are asked to define their own

software projects and determine their team for the

duration of the course, which lasts two quarters.

Each week, there is one lecture and one homework

that relates directly to the lecture and the project.

This homework is posted on the groups chosen

platform and design, mostly blogs. The homework is

then peer reviewed according to criteria by any

group across all cohorts. In previous versions of this

course, students’ work, submissions and peer

reviews as well as forums were located on a single

MOOC platform, chosen by the instructor. The most

significant complaint in the past was dominated by a

criticism of the infrastructure and lack of useful

feedback by other students. The most significant

change for this instance of the course was the

student choice of platform and the public peer

evaluations that had to be shown to the instructor to

gain points towards the final grade in the course.

The students were in complete charge of their

platform. In the past, peer reviews were private and

not taken seriously by all students; all reviews are

now publicly displayed with group name and their

publication under the control of the blog owner.

Autonomy is expressed through self-

determination when choosing a project, the

technology to realize the project and choosing a

team. The key difference in student perception of the

course consisted in extending the autonomy to the

platform for displaying student work in public and

hosting peer reviews. The scaffolding consists of

providing deadlines for set homework, evaluation

criteria and enforcing the use of public peer reviews

on student blogs and including this work as part of a

grade.

Mastery is realized by delaying the grading on

content until submissions undergo several reviews

and revisions, creating a peer pressure towards

excellence in the public forums. Through the use of

peer reviews, guidelines for evaluation and

reflecting on their own homework, final

understanding of the course material is supported.

Blended learning environment consists of 4

hours of in-class time and virtual extension of the

classroom through the online activities described

above. Each week a lecture is given that covers

exactly one new aspect that relates to the next step

required in the project. The subsequent week, some

of the groups present the homework in class and

receive feedback from the teacher. This feedback is

then often used when giving peer reviews to other

project homework, propagating the information to

other groups. This approach blends live feedback by

a teacher with peer reviews. Homework is then

revised and has often been rechecked by peers to

verify the correctness of the change (this point was

not required by the instructor). While the general

guidelines for homework and projects are given, the

specific technical implementation is not prescribed.

As an example, students are required to use an MVC

framework to build a web application and the lecture

focuses on the principles of the Model View

Controller architectural pattern. The programming

language and chosen framework for its realization is

optional. As a result, Laravel (PHP), Rails (Ruby) or

Django (Python) enter into the classroom. Principles

of their use are reviewed by peers and presented as

homework in the classroom, broadening the course

with student-built content. Lecture is then usually

followed by in-class peer review sessions and

project work as time permits. 2 peer reviews were

required by each team each week. Completing the

peer reviews included answering peer reviews with a

feedback. Both had to be shown to the teacher to

obtain points that counted 20% towards the final

grade.

Table 1: Overview of Categories in Student Survey

(Details are given in Appendix A).

Rank these games according to which type best fits for you

(Egoshooter, Facebook, Geocashing, Monopoli)

Rate each of these characteristics from 1-4: (I am creative, I

like to explore new things, I am competitive, I like to work

in a team.)

Grades:

How do you rate this course.

What grade do you expect to obtain.

What grade is sufficient for you.

I feel insecure in this course.

Tools: Topics followed by specific questions (See Appendix

A)

Peer Review

Blog

E-Portfolio

Self-Determinism

Forum/Platform/Classroom

Open Questions:

What do you think about joining all three cohorts for a single

lecture and then splitting into groups?

Which parts of this course setup did you perceive as

particularly difficult in the beginning? Which difficult parts

turned out to be useful? Which parts do you like.

In addition to the team work, individual grades

are given for individual contributions bringing

students’ expertise to the classroom with topics that

are related to the course content. These are called e-

Portfolios and their successful completion consists

of an online tutorial on a topic and a hands-on

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

26

presentation and exercise to be done in class. The

result is posted in a Forum. Over the years this

content is built up to support incoming students with

tutorials on topics that are directly related to the

course.

4 STUDENT SURVEY

Onboarding for the Software Engineering course is

considered to go far into the first semester of the

course. In the past, onboarding has been demanded

of students without any scaffolding. As a result,

students’ perception of the class was negative (site

self). The goal of this survey is to find out how the

current set-up is perceived and whether this

perception is valid across all learner types, based on

the rough self-diagnosis queried in the first section

of the survey. The survey regarding the components

that make up the course and the perception of their

effectiveness is given at the end of the first of two

semesters and was designed keeping reliability and

validity in mind (Schumann, 2012). Because three

classes were taught in parallel, it was possible to

calculate reliability of results across cohorts. The

survey was given within the span of one week to all

three groups (Monday, Tuesday and Thursday).

Students were asked to evaluate their experience

on a four point Likert scale (avoiding the middle

value to get a clear tendency) from “agree

completely” to “disagree completely” regarding the

tools. The questions were very simple and designed

to be closed-ended for comparison. To compensate,

the final section of the survey allowed students free

text to express their thoughts on difficulties and a

different setup of the classrooms. 81 students

currently enrolled in the course answered the survey

during class time.

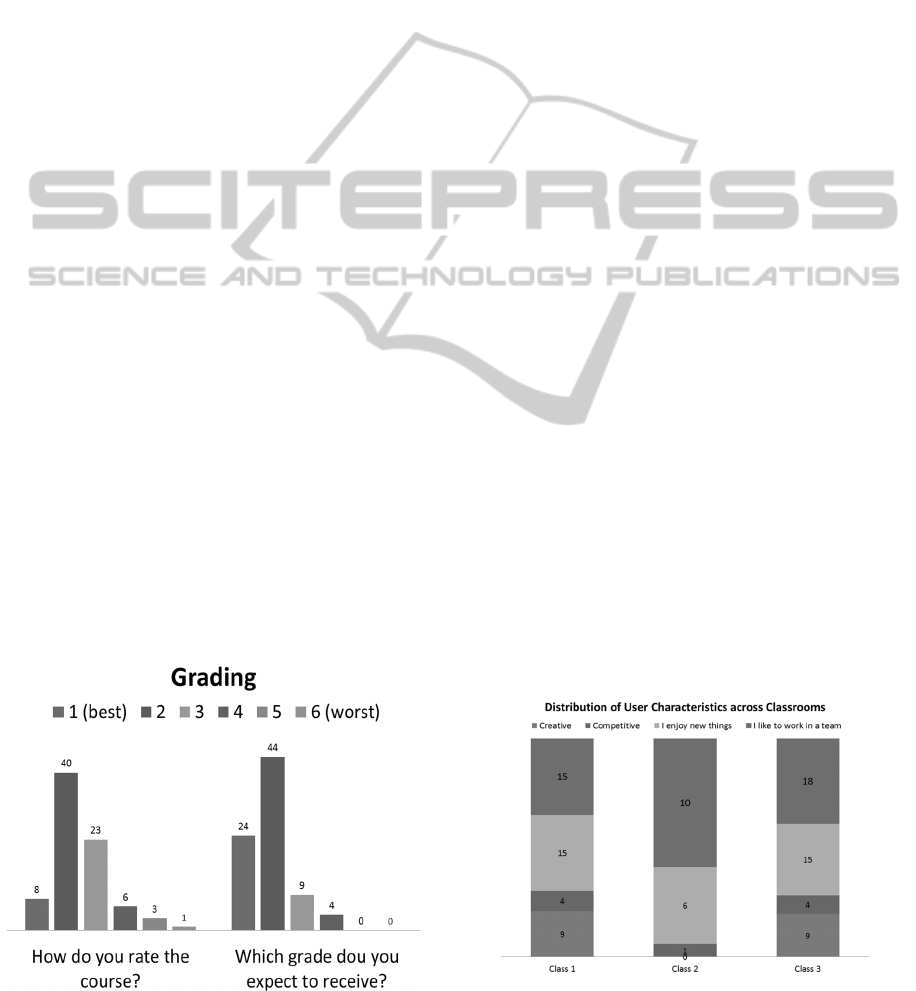

Figure 1: Student evaluation of course and expected grade.

The student survey included four components:

(1) Gamer Type ranked from 1 through 4 (to enforce

a choice) and Learner Types which was chosen on a

likert scale from 1-4 (2) Grading on a likert scale

from 1-6 (German grading system), (3) survey of the

different components used in blended learning on a

likert scale from 1-4 and (4) open ended questions

for qualitative feedback regarding the timing and

room setup and questions pertaining to what was

perceived as the most difficult component during

onboarding. Table 1 lists all Questions. Appendix 1

lists the entire questionnaire.

4.1 Overall Results

Overall, the result of the survey showed that students

are mostly happy with the course and its format.

Figure 1 shows the grades given to the course and

the expected grade the students will receive (final

grading will take place at the end of the second

semester only and final results are not available at

this time). The hypothesis when evaluating the

survey is that most learner types will feel

comfortable with the course because the course was

designed to meet several learner type needs

(Thomas, Ch., 2014). The final step, of including

student control over their platform was met this year.

Results seem to show that the goal of addressing

most students needs seem to have been met (see

Figure 1).

4.2 Self-diagnosed Learner Types

Our past experience shows that students are not

easily able to identify their learner type. According

to the simplified classification based on favourite

prototypical game (according to gamer types) and

personal characteristic, the following student

distribution makes up the three classrooms as shown

in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Number of students according to user

characteristics (multiple selections possible).

ConnectingPeerReviewswithStudents'Motivation-Onboarding,MotivationandBlendedLearning

27

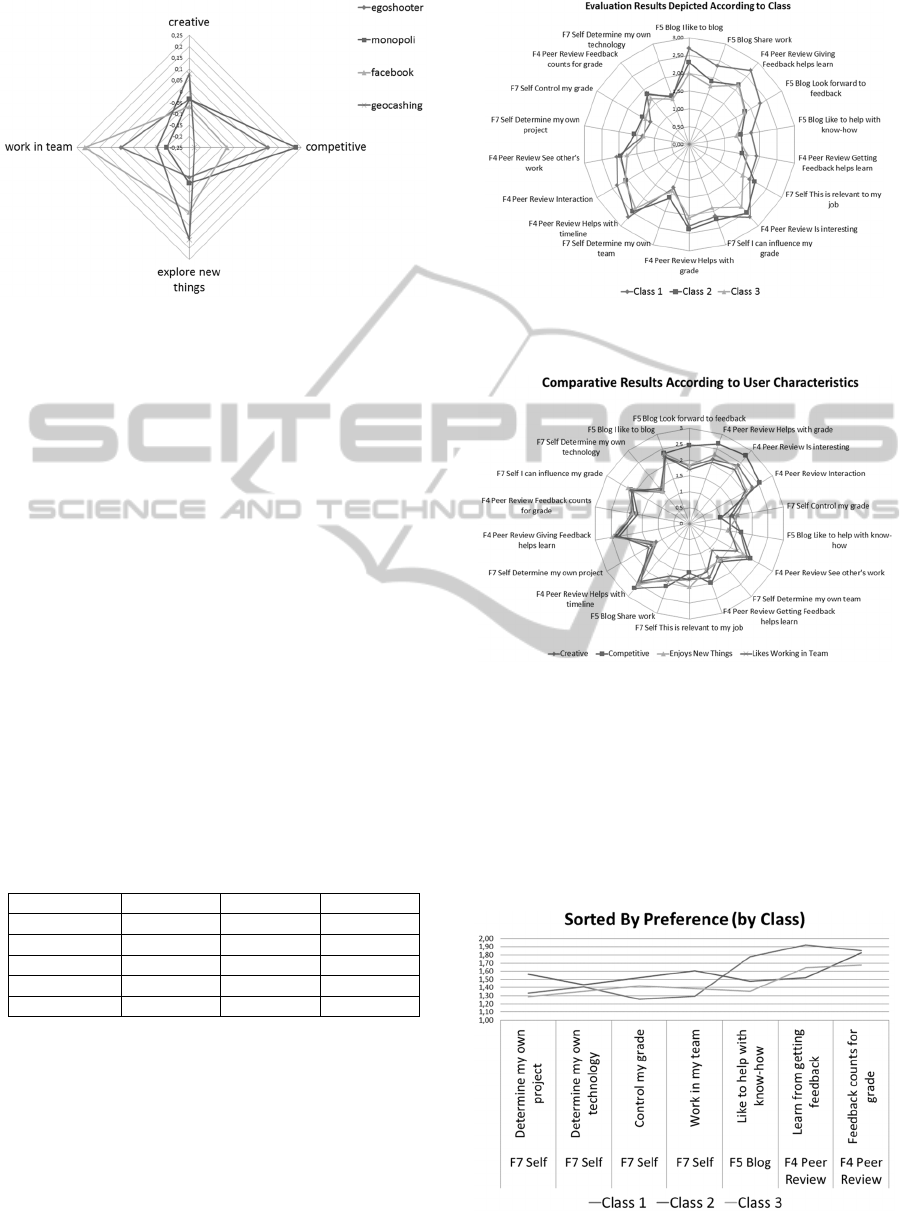

Figure 3: Mapping characteristics onto favourite chosen

game.

The combination of game type and

characteristics is displayed in Figure 3. It is not

surprising that student have multidimensional

characteristics.

4.3 Overall Results across Classes

For each of the five questionnaire categories a

correlation score is computed across the three

courses. Table 2 lists the results. It can be seen that

there is a high correlation across all courses for the

topics of Self Direction, Blog and Peer Reviews,

which were at the focus of the first semester

onboarding process. This indicates that the areas in

focus have had similar acceptance across different

student groups. R-values larger than 0,7 are

generally accepted to show a high reliability. The

rest of this paper focuses mostly on the categories

that correlate well across the classes, namely Peer

Review, Blog, and Self-directed decisions.

Table 2: Correlation/(R-value) across classrooms.

Correlation Class 1/2 Class 1/3 Class 2/3

Peer 0,83 0,96 0,91

Blog 0,98 0,99 0,95

Self-Direction 0,96 0,96 0,97

e-Porfolio 0,75 0,68 0,97

Forum 0,97 0,60 0,77

The overall evaluation scores of the survey items are

depicted in Figure 4 for each of the three classes. It

can be seen that the general rating trends are the

same. However, one classroom was more severe in

rating of question group 5 regarding blogs, while

maintaining the same basic relative pattern. (Class 1

also complained about the lack of time in their

current schedule to the instructor.)

Figure 4: Evaluation results according to classroom, sorted

by disagreement.

Figure 5: Evaluation results according to user

characteristics, sorted by disagreement.

Figure 5 shows how the results compare across

groups of users who have chosen particular user

characteristics with the score of 1 (1=applies

completely – multiple selections possible). It can be

seen that the groups are very similar, while the

competitive students are more severe at rating some

Blog and Peer Review questions.

Figure 6: Highest rated features across three classes.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

28

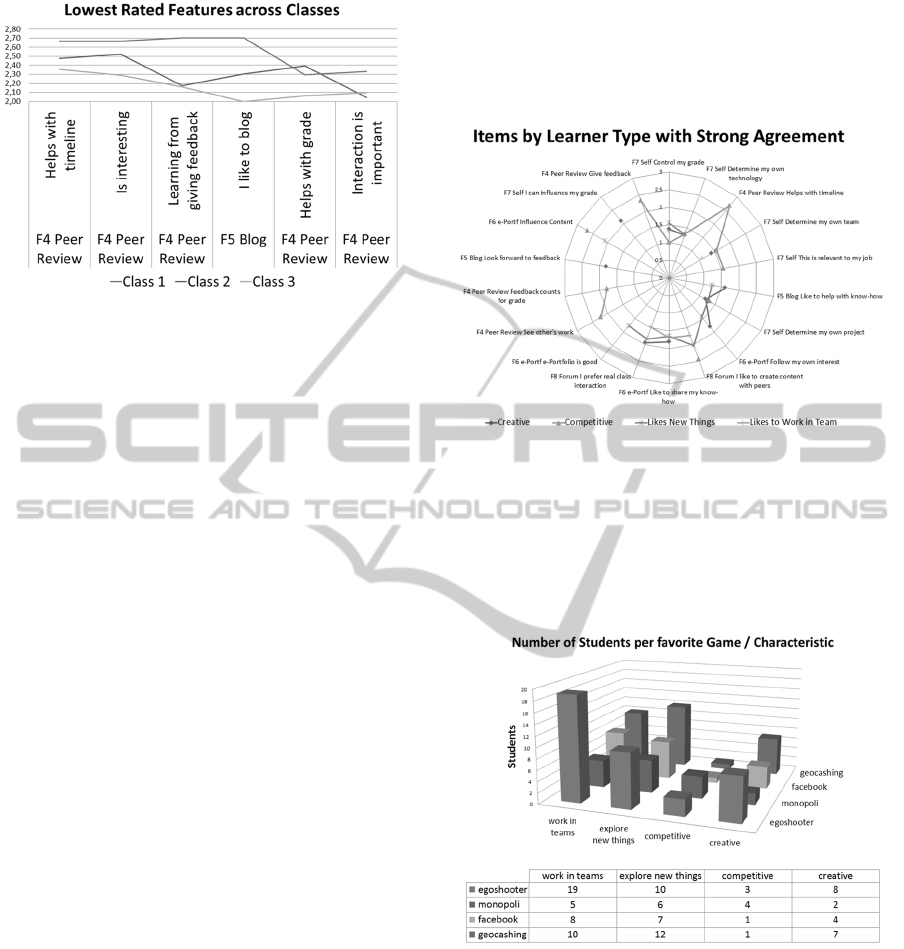

Figure 7: Lowest rated features across three classes.

(2=sort of agree; 3=sort of disagree; 4=disagree).

Figure 6 ranks the top seven rated features of the

course. Adaptation, achieved by letting the students

make their own choices regarding technology,

including blog and peer review as well as

technology used for implementing their project is

appreciated by the students. It is of interest to note

that the peer review seems to be integrated with the

student primary motivation of obtaining a good

grade. The students agree that receiving peer review

feedback is useful in learning the material and

improving it.

Keeping in mind that feedback for all categories

is mostly positive, Figure 7 shows the lowest six

ranked items. Giving feedback on peer reviews

appears here as less highly rated than receiving it.

The answers also seem to reflect that lack of time to

spend on peer review which may not be directly

considered as working in a linear way toward

receiving a grade without wasting time with extra

things (as expected, see also Björk, 2013).

Overall, results can be considered positive and

consistent across three different classrooms. While

the ratings on the items still reflects the straight

forward motivation of students, it can be seen that

the peer review has been integrated into the process

of being successful in obtaining a good grade.

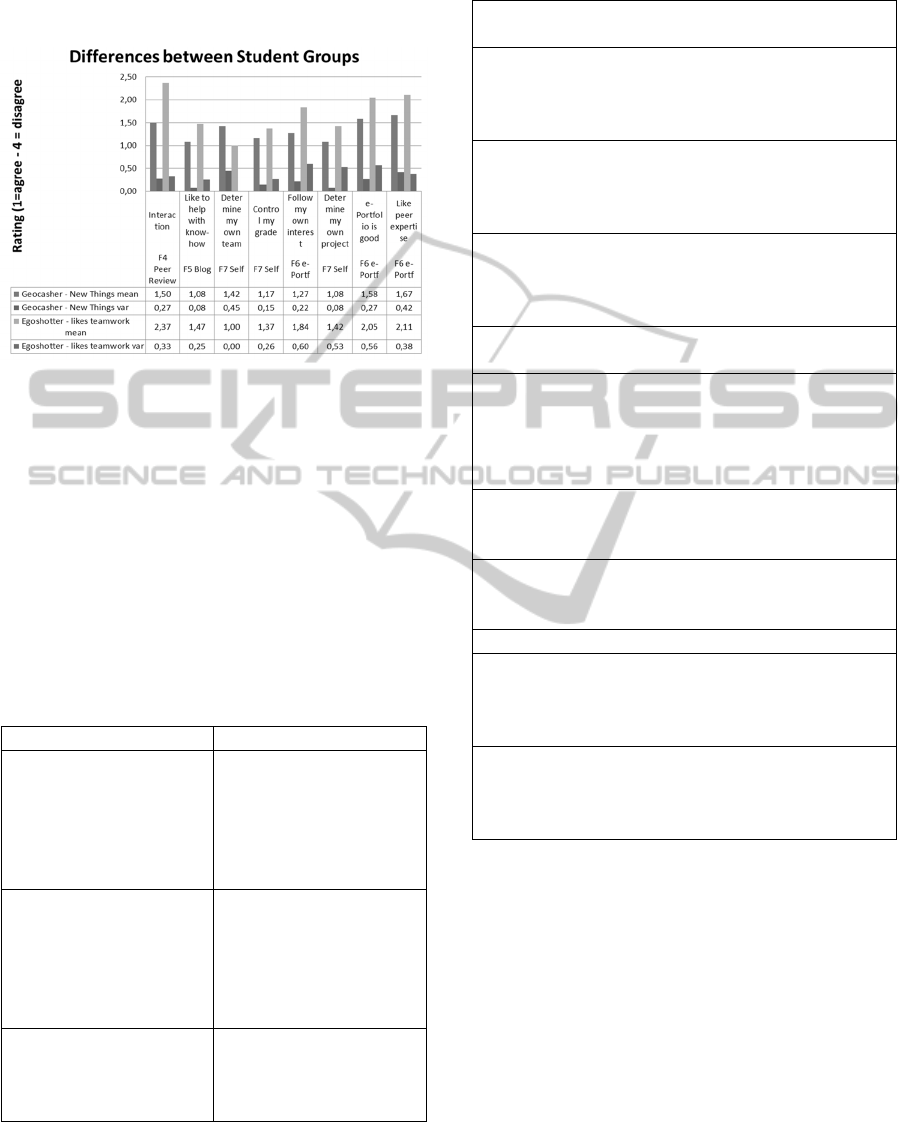

4.4 Differences across Students

Despite the rough estimate, it is interesting to see

whether there are differences in onboarding for

various user types (Creative, Competitive, Exploring

new things, Likes to work in teams). Figure 8

compares those survey items for which the variance

is below .5 for each subgroup. It can be seen that

competitive students agree that peer reviews mostly

do not help with keeping up with the timeline,

whereas other groups of students do not agree within

their subgroup on this point. In contrast, all groups

regardless of their characteristic agree that having

control over their grade is the most important item.

The only other item where all groups agree is the

importance of working in a team.

Figure 8: Features for which students agree on their

assessment within subgroup (variance < .5).

Looking at the two largest groups of students

according to preferred game style and user

characteristics, two groups have a large enough

student sample to be compared according to their

different ranking of the items in the questionnaire.

Figure 9: Number of students according to favourite game

and characteristic (multiple selections possible).

While these subgroups are very small, some

tendencies can be seen that are in line with the

characteristics.

Figure 10 shows that explorers, who like

Geocashing and finding out about new things (12

students) enjoy the interaction with other teams that

the peer reviews support. They also like to help

others with their know-how. Students who identify

most with Egoshooting games and enjoy working in

a team (19 students) rated teamwork uniformly at 1.

ConnectingPeerReviewswithStudents'Motivation-Onboarding,MotivationandBlendedLearning

29

There are, however, no major differences in rating

apparent, which agrees with our expectation in an

environment that is adaptive to user style.

Figure 10: Minor differences between student groups by

game preference and user characteristic.

4.5 Qualitative Feedback

Asking students which parts of the course were most

difficult during onboarding resulted in extensive

written feedback. The comments reflect the

difficulty of getting into the habit of doing the peer

reviews. Furthermore, the amount of time needed to

do the homework was criticized. Table 3 lists the

key attitudes towards the course that are equally

reflected by almost all comments.

Table 3: Points agreed upon by most students.

Positive Considerations Needing Improvement

The basic setup of the

course is good, self-

driven project work, peer

reviews, and mastery

through reworking of

hand-ins.

1 peer review per week

was too much work per

week. Time investment

had better reflect

positively in grade!

Working across

classrooms was

interesting.

The weekly assignments

were not clear enough;

they also should have

been listed in their

entirety at the beginning

of the semester.

Peer reviews help

improve understanding

of the homework.

It is very difficult to get

used to the concept

before understanding the

usefulness.

Some of the following citations demonstrate the

thoughts of students in the course.

Table 4: Comments regarding peer review.

“The basic idea is good, however there is never

enough time.”

“Constant reworking of homework takes some

g

etting used to but is the only way to learn.

F

orming a habit of consistent improvement

contributes to deep comprehension.”

“I think it is good to have a weekly homework in

order to be forced to keep up to date, rather than

pushing everything towards the end of the

semester.”

“It is good that the homework is public. You have

to hand in the homework on time and receive

feedback to improve it. Working across course

s

results in more feedback.”

“Peer reviews take a lot of getting used to. But you

can learn a lot from others.”

“It took a long time to get used to the peer reviews,

the grading system and overall organization of the

course. This improved with time… It was difficult

to determine the homework within all the

information.”

“If the amount of time spent on this course results

in a good grade, it will have been worth the effort.

Otherwise this course is definitely too much work.”

“Because the course has a dif

f

erent structure from

others, it was difficult to get used to it. But it grows

on you and was fun.”

“Difficult to get used to but good.”

“Reworking homework and practical application

helps to fully understand the material. However, it

was difficult to understand the full requirements of

the weekly work. This improved with time.”

“Building habit of weekly assignments was difficult

but turned into routine. This kind of work routing,

f

eedback and taking charge of my own grade was

good.”

5 DISCUSSION

The survey showed that there is general content with

the course. While there are some issues with time

and clarity of content, the overall framework was

accepted by students even though it is perceived as

difficult. It was shown that the same feedback can be

reproduced across three different classrooms. It was

also attempted to show that roughly estimated

learner types seem to react in similar ways to the

course.

Some changes to teaching are still required

(clarifying homework and listing these at the

beginning of the semester) but these are minor

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

30

compared to the fundamental restructuring that has

successively taken place since moving away from

teacher centric learning. The survey showed which

parts of the framework for the class presented more

difficulties for students and which ones were

manageable. We found that peer reviews worked

much better this year with the new setup of student

chosen technology and public peer reviews. While

creating some difficulty for students, these

difficulties were mastered and their benefit

understood. This goal has not been achieved in

previous sessions of the course using tool

functionality out of the box rather than student

created blogs with open reviews and feedback.

Some items, like use of Forum and e-Porfolio

were less well scaffolded than others and agreement

between students was not clear. Both of these have

less direct effect on the grade than peer reviews and

may therefore be skills for higher levels in the

“game”. Future work will show how these can be

better integrated, perhaps across years and not

classrooms, where one class provides information

that is appreciated by subsequent years. This in turn

may motivate those students to provide more

information to students in lower years. The time-gap

between effort and profit is much larger. A typical

quote: “Why should I spend time learning X, when I

don’t need it for my project right now. I will learn it

when I need it. (And by then everything will have

changed anyway)”. The student is probably correct

in today’s IT world. However, learning things that

are not imminently of use is also a step further down

the process of turning extrinsic rewards like grades

into intrinsic rewards of knowledge building and

sharing even if they have no impact on the

points/badges/levels system of the old-school

grading system (Ryan, 2000).

Finally, peer-review and adaptive learning

platforms with respect to user type are open research

questions. By looking at how students design their

own working environment (adaptive in that sense)

more insights can be gained into how to design

automatic systems to perform at the same level.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None of this work would have been possible without

the active role of students in the classroom who are

willing to take the risk and walk along new ways.

REFERENCES

Alario-Hoyos, Carlos, Mar Pérez-Sanagustín, Carlos

Delgado-Kloos, Mario Muñoz-Organero, and Antonio

Rodríguez-de-las-Heras. "Analysing the impact of

built-in and external social tools in a MOOC on

educational technologies." In Scaling up learning for

sustained impact, pp. 5-18. Springer Berlin

Heidelberg, 2013.

Aydin, Selami. "A review of research on Facebook as an

educational environment." Educational Technology

research and development 60, no. 6 (2012): 1093-

1106.

Bartle, Richard. "Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades: Players

who suit MUDs." Journal of MUD research 1, no. 1

(1996): 19.

Bekele, T. A. (2010). Motivation and Satisfaction in

Internet-Supported Learning Environments: A

Review. Educational Technology and Society, 13 (2),

116–127.

Berkling, K. and Thomas, Ch., Looking for Usage Patterns

in e-Learning Platforms – a step towards adaptive

environments, CSEDU 2014, 6

th

International

Conference on Computer Supported Education,

SciTePress, 2014.

Berkling, K. and Zundel, A., Understanding the

Challenges of Introducing Self-driven Blended

Learning in a Restrictive Ecosystem – Step 1 for

Change Management: Understanding Student

Motivation, CSEDU 2013, 5

th

International

Conference on Computer Supported Education,

SciTePress, 2013.

Berkling, K. and Thomas, Ch., Gamification of a Software

Engineering Course -- and a detailed analysis of the

factors that lead to it’s failure. ICL 2013, 16th

International Conference on Interactive Collaborative

Learning and 42 International Conference on

Engineering Pedagogy, 2013.

Bjork, Robert A., John Dunlosky, and Nate Kornell. "Self-

regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions."

Annual Review of Psychology 64 (2013): 417-444.

Deci, E. L. and Ryan, R. M. (2012). Overview of self-

determination theory. The Oxford Handbook of

Human Motivation, 85.

Derntl, M. and Motschnig-Pitrik, R. (2005). The role of

structure, patterns, and people in blended learning. The

Internet and Higher Education, 8(2), 111-130.

Falchikov, Nancy. Improving assessment through student

involvement: Practical solutions for aiding learning in

higher and further education. Routledge, 2013.

Fuhrmann, B. Schneider and A. F. Grasha. A practical

handbook for college teachers. Boston: Little, Brown,

1983.

Gagné, M. and Deci, E. L. (2005). Selfdetermination

theory and work motivation. Journal of

Organizational behavior, 26(4), 331-362.

Garrison, D. R. and Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning:

Uncovering its transformative potential in higher

education. The internet and higher education, 7(2),

95-105.

Graham, C. R. (2006). Blended learning systems.

Handbook of blended learning: Global Perspectives,

local designs. Pfeiffer Publishing, San Francisco,

ConnectingPeerReviewswithStudents'Motivation-Onboarding,MotivationandBlendedLearning

31

http://www.publicationshare.com/graham_intro. pdf.

Hall, S. R., Waitz, I., Brodeur, D. R., Soderholm, D. H.,

and Nasr, R. (2002). Adoption of active learning in a

lecture-based engineering class. In Frontiers in

Education, 2002. FIE 2002. 32nd Annual (Vol. 1, pp.

T2A-9). IEEE.

Kearsley, G. (2000). Online education: learning and

teaching in cyberspace. Belmont, CA.: Wadsworth.

Kim, A.J. Designing the player journey.

http://www.slideshare.net/amyjokim/gamication-

101-design-the-player-journey, 2010.

Lynch, R. and Dembo, M. (2004). The Relationship

Between Self-Regulation and Online Learning in a

Blended Learning Context. The International Review

Of Research In Open And Distance Learning, 5(2).

Retrieved from

http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/18

9/271.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation.

Psychological review, 50(4), 370.

Mohammad, S. and Job, M. A. (2012). Confidence-

Motivation–Satisfaction-Performance (CMSP)

Analysis of Blended Learning System in the Arab

Open University Bahrain.

Nelson, Melissa M., and Christian D. Schunn. "The nature

of feedback: How different types of peer feedback

affect writing performance." Instructional Science 37,

no. 4 (2009): 375-401.

Nilson, Linda B. "Helping students help each other:

Making peer feedback more valuable." Essays in

Teaching Excellence 14, no. 8 (2002): 1-2.

Piech, Chris, Jonathan Huang, Zhenghao Chen, Chuong

Do, Andrew Ng, and Daphne Koller. "Tuned models

of peer assessment in MOOCs." arXiv preprint

arXiv:1307.2579 (2013).

Pink, D. H. (2010). Drive: The surprising truth about what

motivates us. Canongate.

Pujo, F. A., José Luis Sánchez, José García, Higinio Mora,

and Antonio Jimeno. "Blogs: A learning tool proposal

for an Audiovisual Engineering Course." In Global

Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), 2011

IEEE, pp. 871-874. IEEE, 2011.

Rebitzer, J. B. and Taylor, L. J. (2011). Extrinsic rewards

and intrinsic motives: Standard and behavioral

approaches to agency and labor markets. Handbook of

Labor Economics, 4, 701-772.

Riechmann, Sheryl Wetter, and Anthony F. Grasha. "A

rational approach to developing and assessing the

construct validity of a student learning style scales

instrument." The Journal of Psychology 87, no. 2

(1974): 213-223.

Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. "Intrinsic and

extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new

directions." Contemporary educational psychology 25,

no. 1 (2000): 54-67.

Santo, Susan A. "Relationships between learning styles

and online learning." Performance Improvement

Quarterly 19.3, 2006, pp. 73-88.

Schober, A. and Keller, L. (2012). Impact factors for

learner motivation in Blended Learning environments.

International Journal Of Emerging Technologies In

Learning (IJET), 7(S2). Retrieved December 7, 2012,

from http://online-journals.org/i-jet/article/view/2326.

Schumann, Siegfried (2012): Repräsentative Umfrage.

Praxisorientierte Einführung in empirische Methoden

und statistische Analyseverfahren. 6., aktualisierte

Aufl. München: Oldenbourg (Sozialwissenschaften

10-2012).

Scott Rigby, C., Deci, E. L., Patrick, B. C. and Ryan, R.

M. (1992). Beyond the intrinsic-extrinsic dichotomy:

Self-determination in motivation and learning.

Motivation and Emotion, 16(3), 165-185.

Shea, P. and Bidjerano, T. (2010). Learning presence:

Towards a theory of self-efficacy, self-regulation, and

the development of a communities of inquiry in online

and blended learning environments. Computers and

Education, 55(4), 1721-1731.

Tagg, John. The learning paradigm college. Bolton, MA,

USA: Anker Publishing Company, 2003.

Thomas, Ch., and Berkling, K.. Redesign of a Gamified

Software Engineering Course. Step 2 Scaffolding:

Bridging the Motivation Gap. ICL 2013, 16

th

International Conference on Interactive Collaborative

Learning. IEEE, to appear 2013.

Thomas, Herbert. "Learning spaces, learning

environments and the dis ‘placement’of learning."

British Journal of Educational Technology 41, no. 3

(2010): 502-511.

Tinmaz, Hasan. "Social networking websites as an

innovative framework for connectivism."

Contemporary Educational Technology 3, no. 3

(2012): 234-245.

APPENDIX A

The following table lists all items of the

questionnaire used to evaluate the onboarding

process for Software Engineering based on

principles of gamification with blended learning.

Game

Rate the order in which each of these games

most match your interest

G: Egoshooter (killer)

G: Monopoli (achiever)

G: Facebook (socializer)

G: Geocashing (explorer)

User Type

On a scale of 1:agree completely to 4:disagree

completely rate the following:

T: I am creative and like to show that in class

T: I am competitive and want to be the best

T: I like to explore new things

T: I like to collaborate in teams

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

32

Grading

On a scale of 1:best grade 6:worst grade

(German grading system) grade the following:

R: How do you rate the course?

R: What grade do you expect in this course?

R: What grade is enough for you?

R: How secure do you feel in this course?

Peer Reviews

On a scale of 1:agree completely to 4:disagree

completely rate the following:

P: Interaction with other teams is important

P: I like to see what the others are working on

P: Giving feedback helps me to understand

material

P: Receiving feedback helps understand material

P: It helps me to improve my grade

P: It helps me keep my time schedule

P: It is good that the activity counts toward my

grade

P: It is interesting

Blog

On a scale of 1:agree completely to 4:disagree

completely rate the following:

B: I like to create our blog for the project

B: I like to share my work with the others

B: I look forward to receiving feedback

B: I like to help others with what I know

e-Portfolio

On a scale of 1:agree completely to 4:disagree

completely rate the following:

eP: I like to influence the topics in this course

eP: I like that my interests are incorporated

eP: I am interested in peer expertise

eP: I like to share my know-how with peers

eP: Forum is a good place to share this

information

eP: e-Porfolio of others are interesting for me (if I

had the time)

eP: I don’t have time to be interested in ePorfolios

Self Determination

On a scale of 1:agree completely to 4:disagree

completely rate the following:

S: I like to define my own project

S: I like to define my own technology

S: I like to work in a team

S: It is important to have control over my grade

S: I feel that I can influence my grade

S: The content of this course is relevant for my

work

Forum – Platform - Classroom

On a scale of 1:agree completely to 4:disagree

completely rate the following:

F: I prefer asking my peers to tutorials in the web

F: I prefer interacting in the classroom to virtual

F: I like to work with peers to create knowledge

F: The ePlatforms for this course are functional

Open Text Qeustions

Classroom setup and hours

This course has four hours of in-class time and 4

hours of out-of-class study time. How would you

like to change that setup?

Difficulties with Onboarding

This course has a different set up from usual

lecture and exam style. Which aspects did you

like and which aspects where difficult to get used

to.

ConnectingPeerReviewswithStudents'Motivation-Onboarding,MotivationandBlendedLearning

33