Usability in mLearning

Ajinkya Atalatti, Elicia Lanham and Jo Coldwell-Neilson

Deakin University, Burwood Hwy, Melbourne, Australia

Keywords: Mobile Learning, mLearning, Usability, Learning Technologies.

Abstract: As higher education students access educational content using a variety of mobile devices, the question then

arises: Does the content across different mobile devices vary in terms of usability? Does usability determine

a user’s willingness to engage in mobile learning? Hence, it is necessary to investigate the usability of the

learning applications and the mobile devices used to access these applications. This paper outlines results

from a pilot study conducted at a large Australian University. The study highlights the importance of usability

across different mobile devices whilst accessing educational content. This research lays the foundation for a

future study that will broaden the investigation to extend from usability for mLearning to usability for

mLearning.

1 INTRODUCTION

Recent developments in mobile technologies have

given birth to smartphones, tablet computers, and

eBook readers, which offer ‘anywhere and anytime’

learning solutions, as compared to the otherwise

stationary mode of learning (Kim et al., 2006).

Learners are trying to incorporate these mobile

technologies to facilitate their learning endeavours at

an alarming rate (Cheung et al., 2011). Mobile

learning (mLearning) is described as the use of

mobile devices for the purpose of education

(Hewagamage et al., 2012). However, every

technology suffers from certain drawbacks, and

mobile technologies are no different (Peterson, 2013).

Furthermore, the success of mLearning depends

completely on human factors (Kukulska-Hulme,

2007). The field of human-computer interaction

(HCI), which deals with interaction between users

and computers, shoulders the responsibility to tackle

the shortcomings of mobile technologies and to

provide sound and effective solutions for the masses

(Zacarias and de Oliveira, 2012). Usability, a subset

of HCI, is the measure of perceived satisfaction and

acceptability of a system by the user (Nielsen, 1993).

Usability in particular is a major concern for content

developers and designers where man meets machine.

Among the factors that affect usability of mobile

devices, battery life and limitations in input/output

devices are important to focus on (Li et al., 2008).

MLearning, an emergent pedagogy, is affected

greatly with systems and interfaces that lack the sheer

essence of usability principles, and is further hindered

since users have access to a library of mobile devices

which are currently available in the market. Every

mobile device sports different features and it is the

responsibility of mLearning facilitators to adhere to

sound usability guidelines when designing content for

users with different devices.

Many practitioners and researchers are focusing

on the implementation and deployment of mLearning

technologies in tertiary education, however, key

factors such as usability are easily being overlooked.

Conversely, mLearning applications are being

developed and tested for usability (Fetaji and Fetaji,

2011), but researchers seem to disregard the fact that

all students do not own the same mobile devices.

Furthermore, researchers are either developing

usability testing systems, proposing guidelines for

mobile learning applications, or exploring the level of

proliferation of mobile devices for learning in the

educational sector. But there is little research

addressing the usability issues of different mobile

technologies, as students view educational content

across a wide range of mobile devices. The following

questions then arise. Do usability factors differ across

various mobile devices? Do certain usability factors

permit the use of a particular mobile device? Do the

principles of usability vary across different mobile

devices?

The problems discussed above and the

overarching research question, ‘Does usability affect

213

Atalatti A., Lanham E. and Coldwell-Neilson J..

Usability in mLearning.

DOI: 10.5220/0005410702130219

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 213-219

ISBN: 978-989-758-107-6

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

the way users communicate with their devices whilst

accessing educational content?' have motivated this

research study. It explored the popularity of mobile

devices for learning amongst students in the tertiary

education sector and investigated the role of usability

in the adoption of mLearning. This study was

undertaken as part of an Honour’s degree.

The paper comprises of the following sections:

Section 2 outlines the background literature, while

Section 3 describes the survey methodology used

within the study; Section 4 and Section 5 present the

results and discussion respectively. Conclusion and

future work are summarised in Section 6 and 7

respectively.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Mobile Learning

In the age of Mobilism (Norris and Soloway, 2011),

learners and students, bound by family, friends and

work-related commitments, are deciding on flexible

learning options such as distance or online learning

(Albion et al., 2012). Although there is no clear

definition of Mobilism, it can be interpreted as the

rapid rate at which mobile devices are being

developed and used for learning, banking, browsing,

online shopping, work, and leisure purposes. In the

first decade of the 21

st

century, as students were

boarding the Electronic Learning (eLearning) and

Blended Learning train, there was considerable

inclination towards the use of mobile devices for the

purpose of learning (Cheung et al., 2011). The phrase

“anywhere and anytime” was brought to life with the

dawn of mobile technology and the Internet (Cheung

et al., 2011; Son et al., 2004). With wireless, mobile,

portable, and handheld devices as a feasible learning

tool, students could learn on the go and manage their

time more efficiently.

MLearning can refer either to mobile devices and

the technology itself, or the mobility of learners and

their experiences of learning using such devices.

2.2 Usability

Jakob Nielsen, in his book Usability Engineering,

defines usability as the combination of five key

elements including learnability, efficiency,

memorability, errors, and satisfaction (Nielsen,

1993). These encompass the three key elements of the

ISO definition (Peterson, 2013) - efficiency, errors

and satisfaction - and add the area of learnability: that

the acquisition of the knowledge of how to use

something should be easy; and memorability: that

when a user comes back to a device after some time

they need not reacquire how to use it. These elements

play a prominent role in the success of mobile

learning applications. Mobile devices offer plentiful

learning opportunities for users, but face challenges

(Peterson, 2013) such as different screen sizes,

different screen resolutions, limited processing

power, moderate input capacity, restricted network

bandwidth, and network unpredictability (Fetaji,

2008a; 2008b; Nayebi et al., 2012; Rauch, 2011). As

the field of mLearning innovations advances by leaps

and bounds, the ultimate success of the learning

pedagogy relies upon the human factors exhibited

whilst using mobile and wireless technologies

(Kukulska-Hulme, 2007). Usability, an essential

attribute of a system, impacts on user’s satisfaction,

learnability and memorability of the contents of a

system to abate interaction errors which provides for

an effective and efficient learning environment

(Fetaji, 2008b).

Usability of mobile devices features a

comprehensive list of hardware and software specific

usability elements or factors that determine the

acceptability and efficiency of the device as a whole.

Nielsen and Budiu (2012) highlighted four key

usability issues with respect to mobile devices: small

screens, awkward input styles, download delays, and

ill-designed sites. Furthermore, they pointed out that

a user’s experience with mobile devices and personal

computers will never be on a level playing field,

leaving users with the hope that websites will be

reinvented for improved mobile usability (Nielsen

and Budiu, 2012). Traxler also discerned

mLearning’s infantile stage in terms of its

technological shortcomings and pedagogical

significances (Park, 2011).

3 METHODOLOGY

This research study investigated the level of

acceptance of mobile devices by students to cater for

their personal educational needs. An online survey

was used for collecting research specific data for the

study. The study entailed participants answering

survey questions relating to a number of elements

such as general demographics, study behaviours,

external commitments, mobile usage, purpose and

frequency of use, future motivation, and usability of

mobile devices. The survey was delivered to students

currently studying information technology at a large,

public Australian university. It was delivered online

via an email link, from a general departmental email

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

214

account. Ethics approval for the research survey was

obtained from the host institution. All data collected

throughout the survey was non-identifiable in nature

and could not be traced back to the participants. The

survey predominately included quantitative

questions, gathering the data that would address the

research question. However, there were also some

qualitative questions included within the survey to

gather the opinions and thoughts of the survey

respondents.

The design of the survey was informed by the

literature and focussed on the principles of usability

espoused by Nielsen (1993) and Petersen (2013). The

survey results will form the basis of a follow-up study

which will focus on usability of mobile devices to not

only access educational content but also support

learning.

4 RESULTS

The literature review on current mLearning

technologies and usability of mobile devices aided in

the development of the research question. Does

usability affect the way users communicate with their

devices whilst accessing educational content? For the

purpose of data analysis and discussion, the survey

questions were classified into six main categories:

demographic, study behaviour, external

commitments, mobile device ownership, accessing

educational content, mobile usage, purpose and

frequency, future use and motivation, and usability of

mobile devices. In this paper, however, the major

focus is upon the usability of mobile devices whilst

accessing educational content. Other survey results

will be reported in a future publication.

We acknowledge that the reliability of this study

has not been confirmed as this survey research was a

pilot study to discover information on usability of

mobile devices. The information from this pilot study

will be used to perform a larger study that involves

usability testing of learning applications on different

mobile devices which is further discussed in Section

7.

4.1 Demographics

A total of 48 students participated in the survey

comprising of 26 international and 22 local students.

Table 1 details the demographic data of the survey

participants. The participants were also asked to

select the device(s) they currently owned, to which,

46 participants responded that they owned

smartphones, 16 participants said they owned a tablet

computer, and 2 participants said they owned an

eBook reader.

Furthermore, 39 participants identified

themselves as mobile learners (mLearners). Among

the 39 mLearners, 38 participants chose convenience,

31 chose portability, 27 chose accessibility, 16 chose

flexible learning, and 8 chose interactivity as the

reasons for engaging in mLearning.

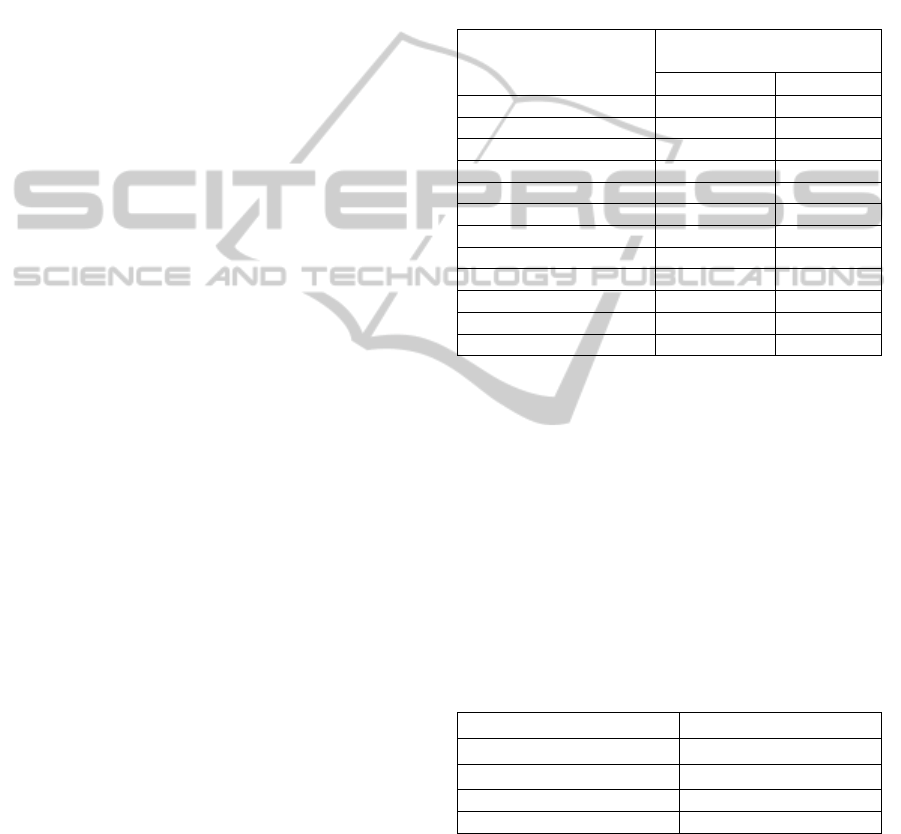

Table 1: Demographics of participants by age and device

used to access educational content (n=48).

Type of Student sorted

by Age Groups

Use of mobile devices to

access educational content

Yes No

International 18 8

18-19 - 3

20-21 4 -

22-23 7 4

24-25 4 1

26 and above 3 -

Local 21 1

18-19 7 -

20-21 8 -

22-23 4 -

26 and above 2 1

Grand Total 39 9

4.2 Usability of Mobile Devices

The final section of the survey comprised of questions

relating to preferred mobile device to access

educational content, reasons for preferring a

particular mobile device, certain features that

participants disliked about their mobile device and,

most important, the usability of their device(s). The

first question asked the participants to select their

preferred choice of mobile device for accessing

educational content (see Table 2).

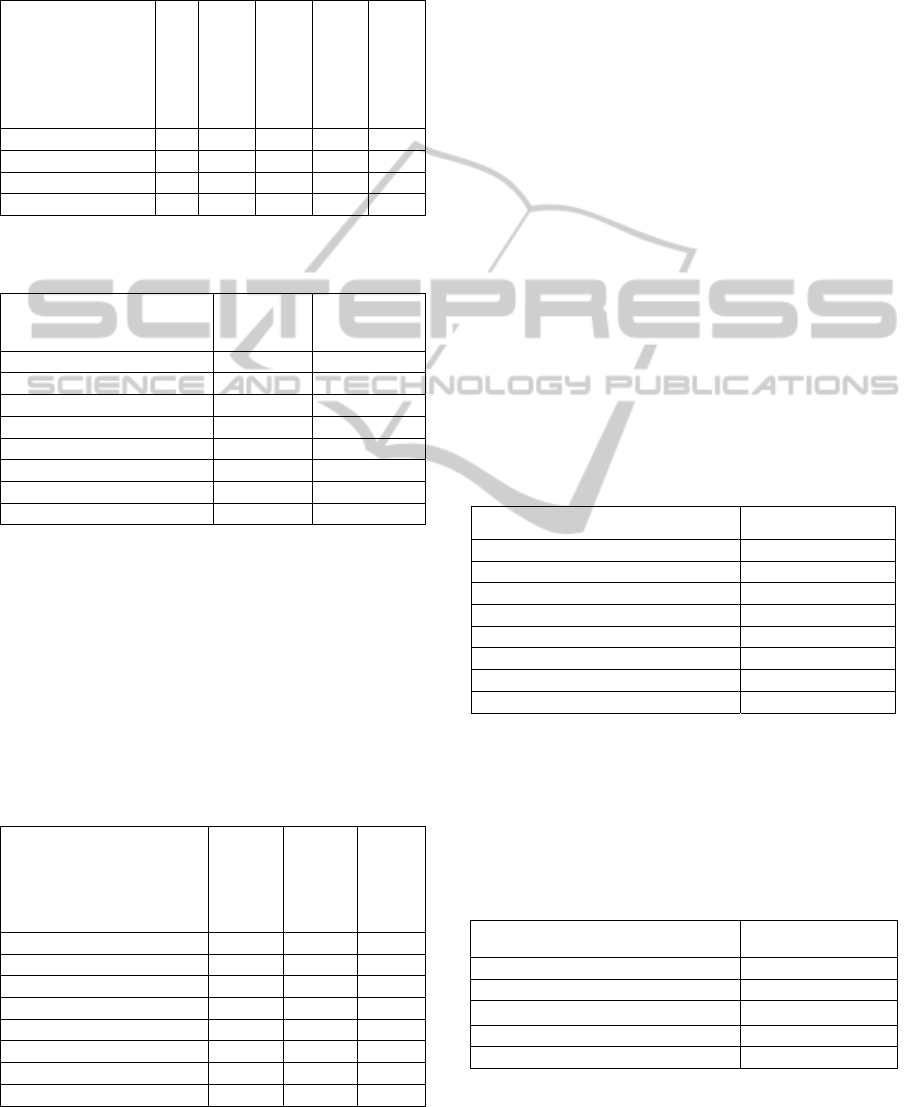

Table 2: “I prefer using ____ for accessing educational

content.” (n=39).

Preferred device No. of students

Smartphone 20

Tablet 15

e-Book reader -

Other 4

Table 3 is an extension of the data extracted from

Table 2 and displays the currently owned mobile

devices by students and their preferred mobile device

for the purpose of accessing educational content.

The second question in this section asked the

participants to identify factors that determined their

choice for using the preferred mobile device (see

UsabilityinmLearning

215

Table 4). Further breakdown of factors based on the

type of preferred mobile device is shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Currently owned mobile devices by participants

and preferred mobile device (multiple responses, n=39).

Currently owned

mobile device

No. of students

Prefer using

Smartphones

Prefer using

Tablets

Prefer using

eBook readers

Prefer using

Other devices

Smartphone 38 20 15 - 3

Tablet 15 3 11 - 1

eBook reader 2 1 - - 1

Other 3 - 3 - -

Table 4: “I prefer using the above mobile device because:”

(n=39).

Factors

Score

(n=39)

Percentage

(n=39)

Easy to use 27 69%

Ample screen size 17 44%

Content is readable 18 46%

Portable 32 82%

Convenient 29 74%

Internet connectivity 23 59%

Ability to multitask 17 44%

Other - -

Amongst the students who preferred mobile devices,

‘portability’ was the most popular factor followed by

‘convenience’. The majority of students also

preferred using smartphones as the devices supported

‘Internet connectivity’ and were ‘easy to use’. As

expected from relatively smaller screen mobile

devices, very few students selected ‘ample screen

size’ and ‘content readability’ as the determining

factors.

Table 5: Breakdown of preferred device and determining

factors.

Factors

Smartphone

(n=20)

Tablet

(n=15)

Other Device

(n=4)

Easy to use 75% 60% 75%

Ample screen size 20% 67% 75%

Content is readable 25% 67% 75%

Portable 95% 67% 75%

Convenient 90% 67% 25%

Internet connectivity 80% 27% 75%

Ability to multitask 35% 40% 100%

Other - - -

Amongst the students who preferred using a

‘Tablet’ for educational purposes (see Table 5),

factors such as ‘ample screen size’, ‘content

readability’, ‘portability’, and ‘convenience’ were the

most popular, followed closely by ‘easy to use’. Very

few students selected ‘Internet connectivity’ and

‘Ability to multitask’ as determining factors for using

tablets. As tablets offer larger screens, it was expected

that the majority of students would choose ample

screen size and readable content as the prime factors

as opposed to smartphones. Also, tablets being larger

in size and consequentially heavier, they are less

portable and convenient as compared to smartphones.

The third question in this section asked students

to describe what they disliked about their mobile

devices. The collated data was qualitative in nature.

Content analysis techniques were used to identify the

themes in the data (see Table 6). Responses such as

“Lagging sometime/freezes of applications, loads

content slow”, “screen is too small, sometimes hard

to navigate, no physical keyboard”, and “Slower to

load pages, screen can be too small, sometimes

lagging happens.” were grouped under the theme

hardware limitations.

Table 6: “Here are some of the things I do not like about my

mobile device(s)” (n=39).

Issues No. of students

Device Performance 5

Internet connectivity 7

Hardware Limitations 7

Software/OS limitation 8

Battery Problems 7

Content Integration 3

Other 3

No issues 6

The final question in this section asked the

participants to comment on which usability principle

they considered the most important when viewing

educational content on mobile devices (see Table 7).

Table 7: “I find ____ as the most important usability

principle when viewing educational content on my mobile

device(s)” (n=39).

Usability principle No. of students

Efficiency 16

Errors or Error Frequency 3

Learnability 13

Memorability 3

Satisfaction 4

Forty one percent (41%) of the students stated that the

speed and accuracy at which they could perform the

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

216

tasks was the most important usability principle,

whereas 33% stated that the speed at which they could

use an interface to perform their desired task was the

most significant usability principle. Only 10% of the

students confirmed that the overall satisfaction

derived after using a device or an application was a

notable usability principle, whereas 8% voted for low

error frequency and functional memorability as the

most important principles.

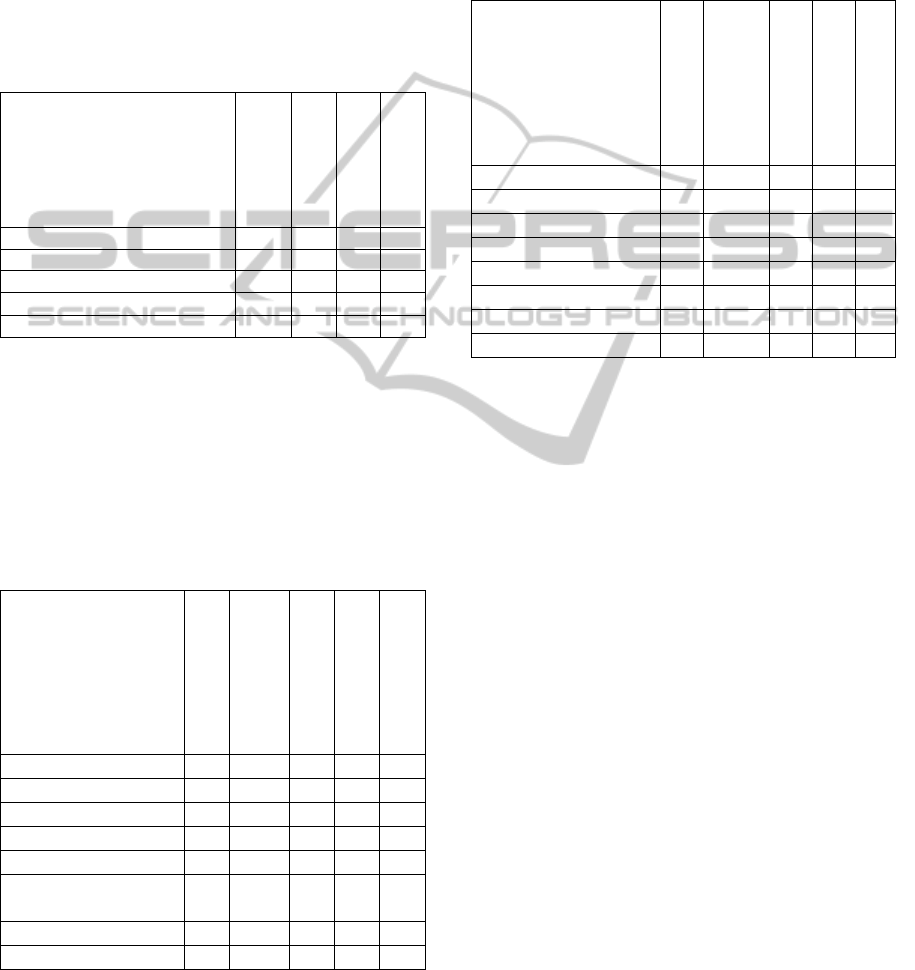

Table 8: Breakdown of preferred device and usability

principles.

Usability Principles

Smartphone

Tablet

eBook readers

Other

Efficiency 10 3 - 3

Errors or Error Frequency 1 2 - -

Learnability 5 7 - 1

Memorability 1 2 - -

Satisfaction 3 1 - -

Table 8 displays a breakdown analysis of preferred

mobile device for learning and the most important

usability principle. This table illustrates that students

who consider a particular usability principle to be

important, on most occasions, prefer a particular

mobile device to access educational content.

Table 9: Cross tabulation of factors, usability principles and

participants that preferred using smartphones (Table 5 and

Table 8).

Factors

(Users that prefer

Smartphone)

Efficiency

Errors & Error

Frequency

Learnability

Memorability

Satisfaction

Easy to use 9 - 4 1 1

Ample screen size 1 - 2 1 -

Content is readable 2 - 1 1 1

Portable 10 1 5 1 2

Convenient 10 1 5 - 2

Internet

connectivity

8 1 5 1 2

Ability to multitask 4 - 2 1 -

Total responses 10 1 5 1 3

Tables 9 and 10 include a cross tabulation to compare

the relationship between preferred mobile device to

access educational content, factors determining the

use of mobile devices to access educational content,

and the most important usability principle. Further

research in this area with a possible controlled

experiment with a larger group would be ideal to draw

solid conclusions.

Table 10: Cross tabulation of factors, usability principles

and participants that preferred using tablets.

Factors

(Users that prefer

Tablets)

Efficiency

Errors & Error

Frequency

Learnability

Memorability

Satisfaction

Easy to use 1 2 4 1 1

Ample screen size 3 2 2 2 1

Content is readable 2 2 4 2 -

Portable 3 1 4 2 -

Convenient 3 1 4 2 -

Internet connectivity - 1 2 1 -

Ability to multitask 2 1 1 1 1

Total responses 3 2 7 2 1

5 DISCUSSION

Due to the limited number of survey participants, it

was difficult to strongly conclude whether these

survey results were an accurate representation of the

entire student population at the University. Further,

the majority of the survey participants were IT

students. However, it was evident that a significant

number of students are currently engaging in

mLearning activities and have access to a range of

different mobile devices. It was observed that local

students were more akin towards using mobile

devices for learning as compared to international

students. The age of the student did not establish any

significance on the use of mobile devices for learning,

however, some patterns were observed amongst

‘digital native’ students, both local and international.

Section 4.2 highlighted different attributes

affecting mobile device usability (Pegrum et al.

2013). Smartphones and tablets have their own

advantages in terms of screen size, convenience,

portability, and ease of use. The results showed that

students used different mobile devices to cater to

different needs, which indicated that usability across

different mobile devices differs and must be taken

into consideration when developing content for a

diverse range of mobile devices. Furthermore, Table

4 presented the issues that can affect the usability of

UsabilityinmLearning

217

a system as perceived by students, such issues are also

reflected in Fetaji et al. (2008) under the following

categories: diminishing the efficiency and

satisfaction during task performance, making

interfaces hard to learn and memorise, and resulting

in unrecoverable errors and high error rates.

Overcoming these hurdles is of the utmost importance

as they are the means to offer sound usable systems

to learners, accessible via different mobile devices,

for effective and efficient learning, and advocating

high rates of satisfaction and memorability, and low

error rates. Upon further investigation, students who

preferred using smartphones for mLearning selected

‘Efficiency’ as the most important usability factor,

whereas tablet users selected ‘Learnability’ as the

most important usability factor. The principles of

usability, thus, vary across different mobile devices

and further research in this area is needed.

Further, in the study were questions that asked

participants to comment on their use or disuse of

mobile devices for learning. The majority of students

engaged in mLearning, pointed towards the

portability and convenience factors of mobile

devices, whereas the students refraining from use of

mobile devices for learning noted factors such as poor

content integration, battery issues, and small screen

size. Given the opportunity, with the potential of

resolving the issues mentioned earlier, 8 of the 9 non-

mLearners had a positive approach towards using

mobile devices for educational purpose in the future.

There seems a strong sense of promise amongst

mLearning practitioners and researchers on the

success and advancement of what could possibly be,

the rapidest growth area in the entire sphere of ICTs

in education (Pegrum et al., 2013).

The survey data presented in this paper shows that

a significant number of students have already

deployed mobile devices in their personal educational

spheres. However, it could be concluded that this

adoption is due to certain features and affordances

offered by mobile devices themselves. Pegrum et al.

(2013) noted the obvious advantage of portability and

convenience factors of mobile devices over the

traditional counterparts such as laptop computers.

Further, the survey conducted in this research study

revealed similar results, exhibiting portability and

convenience as the most popular factors amongst

students preferring smartphones for learning as

compared to ample screen size and readable content

amongst students preferring tablets (see Table 4).

These results therefore demonstrate that students use

a particular mobile device due to its usability

affordance, and the features offered by particular

mobile devices allow for certain usability factors to

stand out. The study also revealed certain aspects of

mobile devices disliked by the students which,

despite portability, convenience, and accessibility,

had a deterring effect on the use of mobile devices.

These shortcomings, although not as significant, can

play a detrimental role on the overall perceived

usability (Raptis et al., 2013). Also, survey results of

the cohort currently not engaging in mLearning,

revealed that usability factors can have a negative

effect on the use of such widespread learning

technologies.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The study aimed at exploring the current level of

adoption of mobile devices for mLearning amongst

tertiary students and to investigate usability’s role in

the adoption process. It was observed that, although a

substantial number of students in this study were

engaging in mLearning, there were certain factors

that inhibited the process of mLearning. As

mLearning is an infantile learning pedagogy, the

potential benefits and affordances are plentiful.

Therefore limiting factors must be addressed early in

the development of any systems or processes so as to

provide a solid learning framework for the young and

growing population of ‘digital native’ users.

7 FUTURE WORK

MLearning’s current stage of infancy and the

limitations presented in this research study have

motivated the contents of this section. Further

research is required with a larger sample group across

different disciplines to cross-reference the results of

this research study, and possibly validate the findings

achieved from this study. In addition, a laboratory

experiment is proposed to investigate if usability

plays a role in the success of mLearning across

various cross-platform mobile devices, and the details

of the experiment are highlighted below.

The laboratory experiment proposed as future

research will focus on usability testing of different

mobile devices. The experiment will comprise of

students that will interact with multiple mobile

devices (smartphones, tablets and eBook readers,

running different operating systems), performing a

series of tasks set by the researcher. The primary

application of focus will be a mobile application

developed specifically for students at the host

university. The participants will be provided with a

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

218

series of tasks to be performed using a variety of

devices. These tasks will comprise of the different

actions a student can perform using the mobile

application. Observations will be recorded based on

the number of gestures/actions required to complete

the task, participant’s physical and mental state,

interaction delays and so on using a five point Likert

scale. The details of data analysis may vary. Once the

tasks are completed, a post-task questionnaire

focusing on usability guidelines and principles will be

handed to the participants. The laboratory study will

focus on user interaction and usability of mobile

devices while accessing educational content. The

study will focus on testing mobile devices while

accessing educational content with the use of existing

usability guidelines. The purpose of the proposed

study will be to determine the difference in usability

across mobile devices with different operating

platforms while accessing educational content. The

research experiment is built upon the hypothesis that

mobile technologies are proliferating and have sound

implications in the educational sector. Users own

different types of mobile devices and usability differs

across cross-platform, different brands, and types of

mobile devices.

REFERENCES

Albion, P., Jamieson-Proctor, R., Redmond, P., Larkin, K.

& Maxwell, A. 2012, 'Going mobile: Each small change

requires another', in Future challenges, sustainable

futures. Proceedings ascilite Wellington 2012, pp. 5-15.

Cheung, S. K. S., Yuen, K. S. & Tsang, E. Y. M. 2011, 'A

study on the readiness of mobile learning in open

education', in IT in Medicine and Education (ITME),

2011 International Symposium on, vol. 1, pp. 133-6.

Fetaji, M. 2008a, 'Case Study: Analyses of Factors that

Influence Mobile Applicative Software', paper

presented to World Conference on Educational

Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications

2008, Vienna, Austria.

Fetaji, M. 2008b, 'Designing Usable M-learning

Application: MobileView Case Study', paper presented

to World Conference on Educational Multimedia,

Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2008, Vienna,

Austria.

Fetaji, M. & Fetaji, B. 2011, 'Devising M-learning usability

framework', in Information Technology Interfaces

(ITI), Proceedings of the ITI 2011 33rd International

Conference on, pp. 275-80.

Hewagamage, K. P., Wickramasinghe, W. M. A. S. B. &

Jayatilaka, A. D. S. 2012, “M-Learning Not an

Extension of E-Learning”: Based on a Case Study of

Moodle VLE, IGI Global, 1941-8647.

Kim, S. H., Mims, C. & Holmes, K. P. 2006, 'An

Introduction to Current Trends and Benefits of Mobile

Wireless Technology Use in Higher Education', AACE

Journal, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 77-100.

Kukulska-Hulme, A. 2007, 'Mobile Usability in

Educational Contexts: What have we learnt?',

International Review of Research in Open and Distance

Learning, vol. 8, no. 2.

Li, Q., Lau, R. W. H., Shih, T. K. & Li, F. W. B. 2008,

'Technology supports for distributed and collaborative

learning over the internet', ACM Trans. Internet

Technol., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 1-24.

Nayebi, F., Desharnais, J. M. & Abran, A. 2012, 'The state

of the art of mobile application usability evaluation', in

Electrical & Computer Engineering (CCECE), 2012

25th IEEE Canadian Conference on, pp. 1-4.

Nielsen, J. 1993, Usability Engineering, Morgan

Kaufmann, San Francisco.

Nielsen, J. & Budiu, R. 2012, Mobile Usability, Pearson

Education.

Norris, C. A. & Soloway, E. 2011, 'Learning and Schooling

in the Age of Mobilism', Educational Technology, vol.

51, no. 6, pp. 3-12.

Park, Y. 2011, 'A Pedagogical Framework for Mobile

Learning: Categorizing Educational Applications of

Mobile Technologies into Four Types', International

Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning,

vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 78-102.

Pegrum, M., Oakley, G. & Faulkner, R. 2013, 'Schools

going mobile: A study of the adoption of mobile

handheld technologies in Western Australian

independent schools', Australasian Journal of

Educational Technology, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 66-81.

Peterson, D. 2013, 'Usability Heuristics for eText and

Digital Course Materials', paper presented to World

Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia

and Telecommunications 2013, Victoria, Canada.

Raptis, D., Tselios, N., Kjeldskov, J. & Skov, M. B. 2013,

'Does size matter?: investigating the impact of mobile

phone screen size on users' perceived usability,

effectiveness and efficiency', paper presented to

Proceedings of the 15th international conference on

Human-computer interaction with mobile devices and

services, Munich, Germany.

Rauch, M. 2011, 'Mobile documentation: Usability

guidelines, and considerations for providing

documentation on Kindle, tablets, and smartphones', in

Professional Communication Conference (IPCC), 2011

IEEE International, pp. 1-13.

Son, C., Lee, Y. & Park, S. 2004, 'Toward New Definition

of M-Learning', paper presented to World Conference

on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare,

and Higher Education 2004, Washington, DC, USA.

Zacarias, M. & de Oliveira, J. V. 2012, Human-computer

interaction: the agency perspective, vol. 396, Springer.

UsabilityinmLearning

219