CORF

®

: Collective Educational Research Facility

Design of a Platform Supporting Educational Research as an Integral Joint Effort

of Researchers and Teaching Professionals

Ruurd Taconis

Eindhoven School of Education, Eindhoven University of Technology, Den Dolech 2, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

Keywords: CORF

®

, Educational Research, Theory-Practice Gap, Research Object, Research Sharing, Data Sharing,

Interoperability, Open Publishing.

Abstract: In educational research, like in other research fields, there is a growing call for sharing data and results. The

public interest in results is clear, and much of the research is done using public money. Besides this,

educational research a gap exists between the research community and research outcomes on one hand, and

secondary school teachers, schools and educational practice on the other. CORF

®

(in English: Collective

Educational Research Facility) is a web-based platform that supports the sharing of research instruments

and research data within and across research projects. CORF

®

community members may be professional

researchers as well as educational practitioners. In this contribution, the concept of CORF

®

is presented and

its major design characteristics are outlined. The system was realized as an internet platform and employed

by various researchers, teachers, and student teachers. A general evaluation and three use-cases are

presented leading to conclusions on the strength and weaknesses of the platform and conditions for adequate

use in practice.

1 INTRODUCTION

The call for increasing the pay-offs of publicly

financed research is getting louder continuously. In

this trend ‘open access publishing’ and ‘data

sharing’ often come to the fore. ICT holds promises

for making research more efficient, increasing the

speed of knowledge production, and allowing for a

more effective spread of results. The European

Community has set a clear course toward data

sharing and open access publications (Horizon

2020), as have various governments, research funds,

and research organizations.

This development also concerns the field of

educational research. In the domain of educational

research, researchers and practitioners have been

struggling with a theory – practice gap for years.

This probably hinders both theoretical progress, but

it definitely limits the innovation of educational

practice (Broekkamp and Van Hout-Wolters, 2007).

Practitioners often have a low opinion off the merits

of educational research in practice (e.g. Gitlin et al.,

1999).

Attempts have been made to narrow this gap.

The Dutch government for example has restructured

the way educational research is funded. The newly

formed in NRO-institute (http://www.nro.nl/) tries to

create closer ties between educational researchers

and practitioners (Admiraal, 2013). In various

Western countries secondary school (student)

teachers are encouraged or even demanded to

engage in research projects (Sinnema et al., 2011).

The aim is to increase teachers’ quality by

supporting their practical understanding of

educational research, and to empower teachers with

tools to improve their educational practice

continuously. Teachers are continuously stimulated

to adapt and develop their professional practice.

Hence, the educational field could benefit from

ICT tools and systems that could help:

to boost data sharing, open access, and the

effectivity and efficiency of educational

research in general,

to bridge the gap between educational research

and educational practice,

to support (student) teachers in secondary

school to perform high standard practical

educational research and learn from it.

To this end, the CORF

®

system (a Dutch acronym

235

Taconis R..

CORF

R

: Collective Educational Research Facility - Design of a Platform Supporting Educational Research as an Integral Joint Effort of Researchers

and Teaching Professionals.

DOI: 10.5220/0005430802350245

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 235-245

ISBN: 978-989-758-107-6

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

which reads in English: Collective Educational

Research Facility) was designed and built. Its design

will be described together with use-cases leading to

a first evaluation.

2 THEORY

Four fields of research are relevant for this paper:

‘open access and sharing of research’, ‘online

questionnaires’, ‘educational research’ and ‘teacher

research’.

2.1 Access and Sharing

The concepts of sharing information and connecting

people are at the very heart of Information and

Communication Technology. The main implications

concerning research are Open Access en sharing of

results.

Open Access implies unrestricted online access

to peer-reviewed scholarly research. Open access

increases the effectivity of research (Harnad and

Brody, 2004). Open Access also disrupts established

structures in information markets concerning

journals, publishers and knowledge institutions.

However, it creates new audiences for research

outputs as well. In the educational domain, for

example, practitioners traditionally not always have

direct access to research outcomes, although it is

clear that they should be a - if not the - main

beneficiary. By creating new audiences, Open

Access is likely to create new demands on

publication formats. For example, enriched

publications that may include datasets that can be

interactively ‘explored’ and/or convincing

visualizations that give insight in key ideas may help

practitioners to understand and employ research

outcomes.

Concerning data sharing, interoperability plays a

central role. There is little benefit in sharing data

that cannot be used by others. Standards play a key

role in interoperability and may also help in

preserving data. Technical standards are needed (e.g.

concerning coding and transferring data). These

allow data to be stored and transferred effectively

and that are readable by a variety of systems.

However, for research data to be useful to others,

we need domain related standards as well. These

should for example describe ‘when’, ‘how’

(instrument) and ‘from whom’ (sample) the data

were collected (Arzberger et al., 2004), making the

data meaningfully interpretable.

It is hard not to notice that in the field of

education much effort has been made to innovate

practice by implementing ICT. This implementation

of ICT seems to focus almost exclusively on

creating effective technology-rich educational

arrangements, sharing learning materials, and

organizing and supporting learning through ICT.

Examples are the creation of open collaborative

learning environments, MOOC´s, and serious games

etc. Only a small fraction of the effort focuses on the

support and strengthening of research of learning

processes and education using ICT.

Among the relatively few ICT experts that have

addressed the process of educational research is

Hunter (2006) who proposes ‘Scientific Publication

Packages’ as a rich, meaningful and transferable

units of research information. Goble, de Roure and

Bechhofer (2013) and Belhajjame et al. (2014)

propose and define so-called ‘Research Objects’,

serving roughly the same purpose as Hunter’s

‘scientific publication packages’, but the goal of

being ‘shared’ rather than being ‘published’. These

and other projects have provided ontologies for

describing education research and its components.

2.2 Online Questionnaires

Online surveys and questionnaires are increasingly

popular in various fields and for various purposes.

Social media often include tools to create polls and

questionnaires. Professionally, online surveys appear

particularly popular for in company monitoring

purposes, market research and customer experience

research. A large number of online survey systems

exist (e.g. Satmetrix, FluidSurveys, Lime survey,

Survey Monkey). Also in the domain of research

some specialized systems can be identified (e.g.

Archer, Qualtrix).

With the exception of Qualtrix which includes a

shared but static questionnaire library, all platforms

seem to follow the strategy of each client building

his own questionnaires (Best Survey Software

Reviews and Comparisons, 2015). Although some

platforms allow sharing of survey outcomes, the

platforms do not support active sharing of raw data

and/or questionnaires between various clients.

The potential advantages of Internet-based

collection of scientific data are numerous: low costs,

reduced time investment, less travelling, quick and

accurate data processing, easy reaching of

(geographically) remote respondents, adaptive

questionnaires, easily administrated lingual and/or

cultural parallel versions, inclusion of multi-media

elements (e.g. including small video’s to react on),

and the use of new questionnaire formats (Zhang,

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

236

2000).

On the other hand there are a number of risks

These include: biased sampling, and biased

responses (e.g. by self-selection mechanisms), large

nonresponse, responses by unintended respondents,

multiple responses by the same respondent, invalid

responses, unwanted revision of previously given

answers (e.g. after comparing with answers

previously given to other questions), and generally

uncontrolled conditions during completion of the

questionnaire (e.g. other persons influencing the

answers). Various authors have described these risks

and possible measures to be taken (Zhang, 2000;

Gunn, 2014; Bosnjak, 2012; Furlan and Martone,

2012).

2.3 Educational Research

Traditional mainstream educational research heavily

draws on psychology, cognitive and social

psychology in particular. Most educational

researchers are oriented accordingly: towards the

construction of generalized theories and models

(Broekkamp and Van Hout-Wolters, 2007).

Low Level of Standardization

Unlike large parts of modern day psychology and

the exact sciences, key concepts in educational

research are defined in various local or idiosyncratic

ways. As a result, general accepted standardized

measuring procedures or instruments are almost

absent. Even for key-concepts such as knowledge,

motivation or learning-styles a wide variety of

instruments exist, all employing their own

definitions. For example, Kleinginna and Kleinginna

(1981) listed 92 definitions of motivations! This

richness is partly beneficial and in accordance with

the multidimensionality of educational processes and

learning. However, it also makes that most datasets

are usable only by the particular researcher who

collected these data. Sometimes, instruments and

data collection procedures are described

incompletely or without enough detail. Such

‘method obfuscation’ (Goble, de Roure and

Bechhofer, 2013) would block meaningful data

sharing.

From a logical perspective, the ´local´ and

sometimes idiosyncratic approaches form a paradox

with the intention to build generally applicable

educational theories. Building such theories upon

locally collected and/or idiosyncratic data seems

impossible. Hence, scientific progress in terms of

general and empirically validated general

educational theories probably requires generalized

instruments and measuring procedures, as well as

producing and sharing interoperable data sets.

Such a development may potentially lift

educational research into a next ‘epistemological

phase’. It would create a situation known from other

disciplines like biology, astronomy, physics or

history. In those domains, data are collected using

instruments and procedures (e.g. expeditions,

telescopes, satellites, CERN) not created or owned

by the local researcher. The researcher may actually

not be the collector of the data at all. Data are

‘bought’ from researchers outside the research team,

or come from library resources. In astronomy, for

example, extend catalogues exist, containing raw

data on thousands and thousands of stars. It is

critical that these are all collected using precisely

defined and shared measuring procedures and

instruments of undisputed validity and quality.

Interoperable data require standardized and shared

instruments and measurement procedures.

Unsatisfactory Impact

Various factors may contribute to the limited impact

that educational research has on educational

practice. A first would be the strict division of

research communities and practitioner communities.

These communities have contrasting work-processes

(reflective versus pragmatic), incentives (production

of formal knowledge versus practical managing the

learning of students) and rewarding mechanisms

(scientific publications verses happy and successful

students). These are ‘two worlds with

complementary approaches and interests’. For

example, Dutch secondary school teachers generally

do not have access to the leading Dutch journal for

teacher trainers, since it is ‘members – only’.

A second reason would be the educational

researchers’ orientation towards building general

theories (Broekkamp and Van Hout-Wolters, 2007).

Many researchers do not have experience as an

educational practitioner. Educational researchers

may be over-confident concerning general theories,

regarding practice as a specific case to be described

using general theories. They may not always be

aware of essential characteristics of particular

educational situations. This can lead to

miscommunication when communicating with

practitioners.

In addition, the multitude of definitions and

measurement procedures, and the detailed – and

sometimes semantic - arguments these may provoke,

can create confusion that constitutes yet another

factor limiting the practical impact of many

potentially powerful findings in educational

CORF®:CollectiveEducationalResearchFacility-DesignofaPlatformSupportingEducationalResearchasanIntegral

JointEffortofResearchersandTeachingProfessionals

237

research. Hence, we presume that standardizing e.g.

key concepts, instruments and measurement

procedures may help to increase the usability of

educational research for practitioners.

2.4 Secondary School Teacher

Research

Unlike the interest of educational researchers in

general theories, a practitioner’s perspective strongly

focusses on the effectual understanding of the

current and local situation. Theories that apply/work

‘here and now’ are preferred. The professional aim

for practitioners may be to improve their

knowledgeable professional performance sometimes

called ‘praxis’. This ‘praxis’ results from a

productive melt of theoretical insight and practical

competence which can be improved by practical

research sometimes denoted as action research (Ax

et al., 2008).

Action research can be defined as ‘a process in

which teachers investigate teaching and learning so

as to improve both their own and their students'

learning, to the benefit of their school’. Here the

focus is on understanding and improving the current

and local practice, and not on producing general

theories or models. Moreover, ‘general’ models may

sometimes be inadequate for the specific situation

the practitioner finds himself in.

Schools and governments too want (student)

teachers to be involved in research for several

reasons (Vrijnsen - de Corte, den Brok, Kamp and

Bergen, 2013). They expect that doing research will

make teachers more aware off possible flaws in their

professional performance, and that it will guide and

inspire them to improve. Hence, a ‘closed feedback

loop’ involving monitoring, reflection and renewed

education is considered essential for practitioner

research. It is about monitoring and evaluating the

effects of the researcher's own actions in the role of

practitioner with the aim of improving practice.

2.4.1 Factors Hindering Teachers’ Research

Secondary school teachers may experience various

problems in doing practitioners research.

Missing Research Context Limits Teachers’

Research

First, teachers picking up research may find

themselves isolated. They are not part of an

educational research environment (Imans, 2014).

Colleagues may sometimes even be negative about

(doing) educational research, or may regard it as a

privilege instead of a supplementary but serious and

demanding task. Tight and compelling schedules

may make doing research even more difficult.

Up-to-date Information and Guidance Are

Needed

Teachers in secondary schools are not always well-

informed about the recent progress in educational

research. Their focus is on practical improvements

and research result tends are often primarily

presented from a researchers perspective. Presenting

research findings for teachers is difficult. It is hard

to build a bridge between the theoretical world and

the practical world. For researchers publishing

outside scientific journals is usually undervalued and

unrewarded.

Hence, teachers are at risk to do projects that are

scientifically ‘naive’ or that suffer from serious

methodological flaws. Teachers may - quite

legitimately - want to focus on practical knowledge,

‘local’ (non-generalized) understanding and

improving of their praxis. However, only valid

research will truly help deepen insight in what is

going on and in how to improve as a practitioner.

Need of Concrete Resources

Apart from this, teachers may suffer from a lack of

research tools and resources. An extensive body of

literature exists aiming at the support of teachers in

doing practical research in the form of books (e.g.

Shagoury and Power, 2012) or websites (e.g.

CoreIdeas, 2014). Inspection shows that materials

and courses focus on the systematic setup of

academic research. Various elements crucial for

practitioners research such as ‘how to use research

conclusions to build a valid action plans’ and

‘convincing your colleagues’, get little attention.

Some courses honour the essential role of ‘closing

the feedback loop’ and address practical research

approaches such as action research (Ax et al., 2008)

and design research (Gravemeijer and Cobb, 2006).

In all cases, actual concrete resources for doing

research, e.g. questionnaires, instruments and

statistical tools that fit the teachers’ particular

research situation, are quite rare. A lack of such

concrete resources may stimulate the use of self-

constructed instruments. This is time-consuming and

most often results in instruments that lack

sensitivity, validity or reliability. This may limit

teacher professionalization and may lead to

meaningless or misleading results. Providing

teachers with concrete validated instruments and

other concrete resources may help them to

professionalize more effectively and would make a

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

238

more direct contribution to school innovations.

Instruments

Nevertheless, various instruments developed by

educational researcher are practical and valuable

diagnostic tools for teachers. The various

instruments produced at the SMEC institute are

convincing examples that are used worldwide

(Fraser, 2012).

Making available such instruments may boost

secondary school teacher research and

professionalization, particularly when theoretically

instruments can be adapted to the teachers specific

situation/needs. In particular when presented in a

practical and compact format, making it easy to

administer the data or to compare the outcomes with

results attained elsewhere. Using online

questionnaires would be an effective and practicable

approach (Birnbaum and Reips, 2005). Practitioner

research could benefit from easy-to-use instruments

derived from scientific counterparts (Feldman,

2007).

2.5 Focus and Research Aim

In this paper, we will describe the CORF

®

system

and three use-cases. We end with conclusions on the

merits, weaknesses and possibilities of the CORF

®

system. We will particularly focus on bridging the

gap between educational research and educational

praxis, facilitation of teacher research and

stimulating scientific progress in educational

research. Finally, we will discuss some directions to

improve the system still further.

3 CORF

®

The CORF

®

system is an Internet platform that

facilitates (student) teachers and researchers to

collaborate in doing educational research.

It employs a database containing research

projects each comprising various objects such as

instruments, data sets and reports/publications.

These objects can be shared within the CORF

®

community. Instruments typically are editable

questionnaires that can be administered online.

Using CORF

®

these can be administered as online

questionnaires to respondents inside or outside the

community. Hence, CORF

®

defines a working

environment for building, sharing and adapting

questionnaires, data and other research components.

For granting access, CORF

®

employs role-based

access control strategy. The various roles each

require the user to accept a specific user agreement.

Important roles and their rights (shown in italics) are

(Taconis et al., 2007):

Anonymous: has the right to see ‘open’

instruments, data sets and reports, complete

questionnaires anonymously;

Respondent: has the right to complete

instruments/questionnaires retraceable to the

user account, see instruments, data sets and

reports ‘shared within the community’;

Instrument Administrator: has respondent rights

+ the right to collect data with existing

instruments, (teachers may take this role when

collecting data for a project they participate in)

Author: has instrument administrator rights +

the right to create/share/adapt instruments;

Editor: has author rights + the right/obligation

to peer review data sets, instruments and

reports/articles.

In addition, CORF

®

users can make specific

exception concerning visibility and sharing of the

various instruments, data sets etc. they own.

3.1 Components and Functionalities

Key features of the CORF system are listed below.

In the next sections these will be described more

extensively.

Library of Active Online Instruments

the active library contains various standard

scientifically validated instruments,

al instruments can be administered online.

Supporting Practitioners Research

CORF

®

supports instrument types specifically

tailored to teachers research (storyline, rep grid,

etc.),

online instruments produce an individualized

response page that pops up immediately after

completion of the questionnaire by a

respondent. Its set-up is an editable part of the

instrument that can be tailored as to produce

detailed feedback to the respondents (Taconis,

et al., 2014),

individualized response pages can be made

visible to the instrument-administrator,

the collected data can be extracted to be

processed in statistical software packages.

CORF®:CollectiveEducationalResearchFacility-DesignofaPlatformSupportingEducationalResearchasanIntegral

JointEffortofResearchersandTeachingProfessionals

239

Sharing and Adapting Research Instruments

(if permission is granted by the owner)

instruments can be shared, copied, adapted,

combined and made part of a user’s own

research project.

Sharing Data Sets

(if permission is granted by the owner) data sets

can be shared and made part of a user’s own

research project.

Sharing and Open Access Publication of

Reports/Articles

(if permission is granted by the owner) reports

can be shared and can be published as open

access articles.

Certificates

instruments, data sets and reports/articles can be

submitted to a board within the community for

peer review

3.2 Concept and System Design

A key idea behind CORF

®

is that educational

research is a collaborative endeavour. It is primarily

performed in a team working on a project. However,

research teams are part of a larger research

community. Community members may play various

roles in different teams such as inspirer, (potential)

team member, source of knowhow, critical friend,

formal evaluator, audience or customer. In

educational research, teachers and schools should be

included playing their role in this community.

As research projects progress various

‘documents’ are produced such as ideas, plans,

hypothesis, assumptions, literature reviews,

instrument, data sets, and report are created. In a

classical approach to research, these are typically

shared within the project team while some may be

shared with close colleagues. However, by sharing

with community members outside the project team

and/or outside the circle of close colleagues, the

efficiency of the research process can probably be

increased. In particular when sharing instruments

and data sets.

Hence, research projects within the CORF

®

system are conceptualized as a compound data

objects comprising e.g. research plans, instruments,

methodological schemes, data sets, reports etc. The

platform facilitates sharing, the sharing of

instruments, data sets and reports in particular.

Project teams in CORF

®

can import instruments

and data sets from other research projects within

CORF

®

. These shared objects can be combined with

the team´s own instruments and/or data, or with data

from yet another project. In theory, a project can

even entirely draw on data sets from other projects.

In this, the availability of the corresponding

instruments is crucial for interpreting such data sets.

If instruments are imported in a project, these can be

readily used to collect new data. Alternatively, the

imported instruments can be adapted and saved as

‘new instruments’, before new data are collected.

A key issue concerns the validity of online

questionnaires. We think that that community

approach taken by CORF

®

adequately counters most

of the threats tot data quality since a key aspect of

the hazards listed above comes from the lack of any

link between the respondent and the research. In the

community approach taken by respondents typically

are linked to the research though not in a way

influencing their responses. Respondents will

typically be students a secondary school classroom,

being asked by their teacher to complete the online

questionnaires. In this the teacher typically acts as an

instrument-administrator, supporting the cooperation

of the students but not involved in the research itself.

In addition, the CORF system provides various

systems to prevents double or unwanted entries,

such providing the teacher with a set of unique

access codes for his students.

3.3 Database Ontologies

Within the CORF

®

database, the compound structure

of ´research project´, comprises elements from three

distinct ontological trees: instruments, data sets, and

reports. Each carries its own attributes; metadata and

addenda in particular. Other research components

like plans and hypotheses are included within the

metadata.

Figure 1: The compound object ‘Research project’.

3.3.1 Instruments and Instrument Sharing

Instruments can be of various sub-types such as

Juridical addendum

Technical meta data

Scientific Certificate

Juridical addendum

Technical meta data

Scientific Certificate

Juridical addendum

Technical meta data

Scientific Certificate

Instruments

(type: active code)

Data sets

(type: .csv)

Articles/Reports

(type: .txt)

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

240

‘interview scheme’, ‘observation scheme’, or

‘questionnaire’. Instruments of the questionnaire

sub-type can be actively administered as online

questionnaires. Instruments as well as their parts

(sub-questionnaires or items) can be shared through

copying. Copies will be personal and can be adapted

by the user (for other sub-types these features are not

supported in the current CORF system). When

copied, the juridical addendum also sticks to the

copy while a scientific certificate is lost (no second

scientifically certified copy can exist).

3.3.2 Data Sets and Data Sharing

Data sets are the result of administrating an

instrument to a particular group of respondents. Data

sets cannot be copied or edited and they are shared

by granting access to another CORF user (not by

copying). Typically, they are shared with the

instrument owner, as an instrument is administered

by another user.

3.3.3 Sharing Reports and Publishing

Articles

In a way, research projects shared within the CORF

®

already constitute enriched and ´open´ publications –

at least within the CORF community. Publishing a

´Research Project´ is creating an open publication

freely accessible outside the CORF community. This

requires review and accordance by the peer review

board within CORF

®

as either a ‘professional

publication’ or a ‘scientific publication’. Since the

related data and instruments are directly available in

the CORF system, the publication is ‘enriched’.

Assessing the components, however, requires an

adequate CORF account.

3.4 Metadata

For all three types of objects, metadata are attached

within three categories (i.e. instruments, datasets and

reports/articles).

Technical metadata comprise: version, family,

date of production, last date of adaptation, etc.

Educational metadata can significantly enhance the

effective description, search and retrieval of online

learning objects and educational resources

(Chatzinotas et al., 2014). These comprise age of the

student population, school type, school subject, etc.

The juridical addendum comprises information

on ownership, authorship and rights concerning

components. Juridical issues are also taken care of

by through the role-based access control system,

user agreements and privacy regulations.

Qualifications in the juridical addendum may

prevent particular actions such publishing externally

or sharing.

The scientific certificate concerns scientific

information on usability, scope of

applicability/validity, sample size (for data) and

issues of scientific quality.

3.4.1 Research Certificates

Research certificates are produced on request by a

board installed within the CORF community that

comprises high ranking academic researchers as well

as practitioners. The board provides high quality

peer review. Two types of certificates can be

granted: ‘scientific’ and ‘practitioner’.

The workflow for the certification procedure is

implemented within the CORF system. It applies to

each of the ontological object-groups separately.

E.g. an instrument can get a scientific certificate

indicating its scientific merits in terms of validity,

reliability, sensitivity, reproducibility etc. for use

within an indicated domain of applicability, against

generally accepted scientific standards (Trochim,

Donelly, 2006). The board typically needs data

collected using the instrument to be able to judge

this.

Also, data sets may be awarded a certificate. This

requires the use of a certified instrument, proof of

unbiased data collection procedure (e.g. controlled

circumstances during data collection, respect for

applicable codes of conduct), data quality (e.g.

number of: missing values, cases with suspect data-

patterns) and sample (e.g. within the instruments

domain of validated applicability).

A project that reuses a certified instrument

developed elsewhere may produce a certified data

set, leading to a report which is scientifically

certified. To acquire the latter the board will

evaluate the whole research project (including

instrument and data) in a way analogous to scientific

journals reviewing submitted papers. Certificates of

the ‘practitioner’ type are granted along the same

lines, but with criteria that emphasise practical value

over scientific merits.

Certificates are visible to all CORF users, and

help them to select instruments for adaptation and/or

reuse or data sets that they consider apt for their

purposes. E.g. teacher may want to use scientifically

certified questionnaires as a basis for constructing

their own (no longer scientifically certified)

questionnaires. Later on they may apply for the

certification of these new instruments, e.g. on the

CORF®:CollectiveEducationalResearchFacility-DesignofaPlatformSupportingEducationalResearchasanIntegral

JointEffortofResearchersandTeachingProfessionals

241

practitioner level.

3.4.2 Community

The CORF system defines a community. Various

users may have interest in different issues, from

different professional perspectives, and on different

levels of proficiency. Members all bring to the

CORF community their questions, expertise,

instruments, data and research results. In return, they

get answers, knowledge and support from each

other. PhD-researchers, for instance, appreciate

CORF

®

as a way of efficient data collection and as a

way to connect more closely to their primary

audience: teachers. Teachers and schools appreciate

the opportunities to get easy access to research

capacity that may be able to help them to solve

problems emerging in school-practice.

Teachers and student teachers can improve their

teaching and research skills while using data and

instruments. They can also collaborate with other

teachers as well as researchers.

4 EVALUATION

Currently, CORF

®

comprises over 2000 accounts

and 350 projects. Over 20.000 questionnaires have

been administrated. Approximately 20% of the

activity is due to participating teachers, student

teachers in particular. On the other hand, not all

accounts are simultaneously active, and activity

seems decisively stimulated by the adoption of the

system by teacher training institutes for student

teachers, PhD-projects and practical surveys and

inquiries.

Various modes of using the system occur: using

standard questionnaires for quick feedback, adapting

and combining standard questionnaires, creating

entirely new questionnaires, using specific practical

instruments that are otherwise electronically

unavailable (e.g. storyline - see below).

4.1 Survey and Interviews

We administered a small survey (n=360 on the

general features and usability of the CORF-system.

Apart from this, a series of interview was conducted

with CORF users.

The interviews focused on the appreciation of the

various components and aspects of the system. The

interviews were structured and addressed a series of

key issues: reasons/incentives to use CORF

®

,

usability, the library of active instruments, particular

instrument types (see below), administration of

online questionnaires, instrument sharing/reuse, data

sharing, the peer review system, publishing

facilities, etc. Researchers as well as practitioners

were interviewed.

The survey and interviews indicated that the

CORF system was stable and performed adequately

(Taconis, De Jong and Bolhuis, 2007). Some users

reported difficulty in understanding how the system

handled instrument-versions. It also became clear

that general usability could be improved and the

various options implemented were not always

intuitively clear.

A main result from the interviews was that

teachers and young researchers at the beginning of

their careers appreciated the crossover between

teachers and researcher. Teachers indicated that this

was an opportunity for them to connect to

researchers, and that this was of key value for them

to participate. They also appreciated the library of

instruments. On the other hand, they complained that

‘there are not too many people around’.

These two groups of respondents also liked the

possibility to share and publish without the high

threshold that occurred when submitting to an

official journal (Taconis et al., 2014). In particular

informal papers, ‘try-outs’, presentations and other

half-products that would otherwise “would be

exclusively shared with my hard disk”.

Senior researchers clearly had a different focus.

These often had supervising roles in research rather

than operational ones. These researchers appreciated

the possibility of administrating questionnaires

online because of low costs, efficiency and the

availability of high standard instruments within the

system (reusability). These respondents also liked

the quick feedback pages, which they identified as a

time-saving way to provide learners with the

feedback.

From the interviews, it becomes clear that doing

peer review of publications was not the participants’

priority, in particular due to a lack of scientific

status. However, it was widely recognized that the

quality of instruments in CORF

®

should be easily

recognizable, and that this required peer review.

4.2 Use-cases

Use-cases can illustrate the key characteristics of the

CORF-system.

4.2.1 Use of Standardized Questionnaires

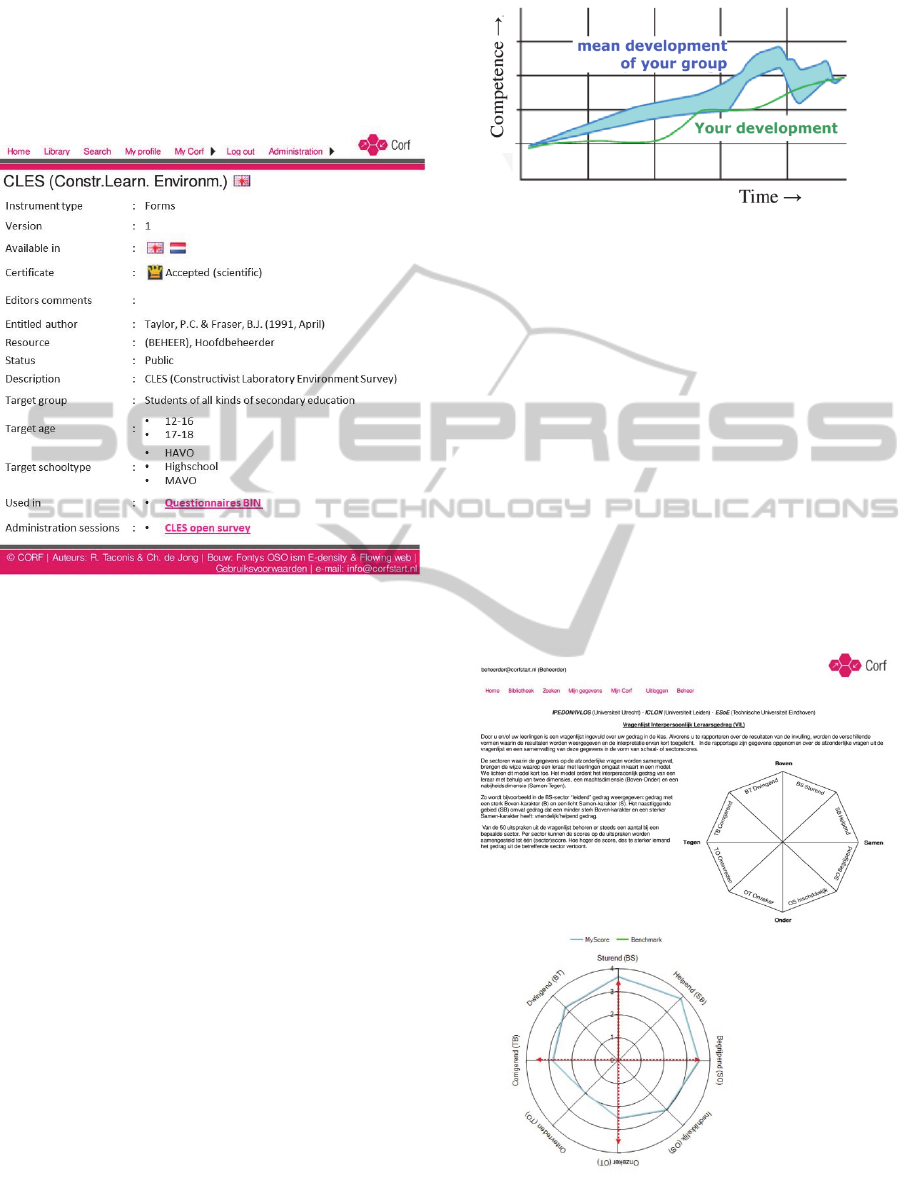

Figure 2 shows the metadata page on the

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

242

CLES-questionnaire (Fraser, 2012) implemented in

de CORF library as an active online questionnaire.

This instruments has been reused/adapted several

times, both at a scientific level in PhD students, and

at the ‘practitioners´ level by student teachers.

Figure 2: Metadata of the standard instruments CLES.

4.2.2 Storyline Instrument: Innovative

Pract-icable Scientific Evaluation

Instruments

‘Storyline’ is originally developed as an interview

format. The general idea is that the respondent is

asked to look back on a particular period of

education and to draw a graph depicting the his/her

development concerning a particular developmental

aspect – typically knowledge or skill of a particular

kind (Beijaard, 1995). The graph´s shape generally

shows various bends, discontinuities, steep and/or

curved sections, etc. These correspond to particular

developmental events and circumstances. The

respondent is subsequently asked to explain the

shape of the graph (Figure 3). This reveals the

mechanisms and circumstances the respondent

considers relevant. The whole procedure forms a

thorough and focused but time/consuming way to

evaluate learning processes as perceived by the

learner.

In CORF

®

, the time-consuming interview format

is recast into a compact electronic format, which is a

combination of the online drawing of the graph and

answering an adaptive set of open questions that

map the respondents’ explanation. Moreover, the

CORF

®

system offers immediate feedback to the

Figure 3: A Storyline diagram form CORF feedback

(respondent’s explanations no shown).

respondents as well as to the instrument-

administrator, which includes a graph of the

respondents’ peer-groups average (self-perceived)

development.

This practical format became popular with

CORF users employing it for teacher training

evaluation and research into the development of ICT

use by science teacher.

4.2.3 QTI: Immediate Specific Feedback

with Scientifically Established

Instruments

A closed feedback loop is essential for teacher

research. Each CORF questionnaire produces a

Figure 4: Immediate feedback for teachers (and students)

on electronically administrated CORF questionnaires

using diagrams and condition texts.

CORF®:CollectiveEducationalResearchFacility-DesignofaPlatformSupportingEducationalResearchasanIntegral

JointEffortofResearchersandTeachingProfessionals

243

response page. This page can be tailored as to show

individual scores, total-scale and sub-scale means to

both the respondent and the questionnaire-

administrator.

Figure 4 shows the example of detailed feedback

in the case of the QTI-questionnaire (Questionnaire

on Teacher Interaction – e.g. Wubbels et al., 2006).

5 CONCLUSIONS

The CORF system works reasonably well. The

design and technical implementation match

expectations on all key issues. Examples are the

conceptualization of the compound object ‘research

project’, juridical issues, metadata, administering

questionnaires, sharing instruments.

A first points of improvement is making the

handling of versions more transparent. Also the user

interface could be improved. Besides this, the set of

educational metadata could be further developed, i.e.

by using ontologies developed elsewhere (Duval,

2001).

Concerning the first research question, we

conclude that CORF

®

technically provides the

facilities for data sharing and open access

publications. It also recognizably boosts research

efficiency as is well recognized by senior

researchers. CORF

®

also clearly helps to promote

the use of standardized tests amongst PhD students,

in particular when supported by supervisors.

Concerning the second research question, both

teachers and young researchers appreciate the

opportunities mutually get in touch and the low

threshold publication opportunities CORF

®

provides. The quick feedback page really adds value

to the electronic questionnaires.

Concerning the third research question, we find

that teachers appreciate CORF

®

for providing access

to acknowledged instruments. Indeed (student)

teachers started using scientific instruments,

standard questionnaires from the library and

storyline in particular.

Overall, however, the contribution CORF

®

makes to strengthening educational research and

supporting teacher research appears limited. The

CORF system as such performs adequately, but the

scale of the active community seems too small to

capitalize on the various opportunities offered.

Certificates, for example, are implemented in a

well manageable way. Nevertheless, in a small

community a uses can still judge the various

instruments directly, and certifications appears as

devious and the ‘burden’ of reviewing does not pay

off.

It is observed that most CORF users are linked to

a school or a teacher-training institute or research

institute that actively promotes the use of CORF

®

.

An obvious first step to enlarge the CORF

community would be to involve more institutes.

REFERENCES

Admiraal, W. (2013). Academisch docentschap: naar

wetenschappelijk praktijkonderzoek door docenten.

(Academic teachers: practical scientific research by

teachers). Inaugural lecture, Leiden University, Leiden

The Netherlands.

Arzberger, P., Schroeder, P., Beaulieu, A., Bowker, G.,

Casey, K., Laaksonen, L., ... & Wouters, P. (2004).

Promoting access to public research data for scientific,

economic, and social development. Data Science

Journal, 3, 135-152.

Ax, J., Ponte, P., & Brouwer, N. (2008). Action research

in initial teacher education: an explorative study.

Educational action research, 16(1), 55 – 72.

Beijaard, D. (1995). Teachers' prior experiences and actual

perceptions of professional identity. Teachers and

teaching: theory and practice, 1(2), 281- 294.

Belhajjame, K., Zhao, J., Garijo, D., Hettne, K., Palma, R.,

Corcho, Ó., ... & Goble, C. (2014). The research

object suite of ontologies: Sharing and exchanging

research data and methods on the open web.

Best Survey Software Reviews and Comparisons (2015).

http://survey-software-review.toptenreviews.com/

Birnbaum, M. H., & Reips, U. D. (2005). Behavioral

research and data collection via the Internet. In: Vu,

K. P. L., & Proctor, R. W. (Eds.) The handbook of

human factors in Web design, pp. 471-492. Boca

Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Bosnjak, M. (2012, November). ́No response is also a

response ́. Interpretations for and implications of

(non)response in self-administered surveys. Invited

talk given at the 6th Tivian Symposium, November 9,

2012, Cologne, Germany.

Broekkamp, H., & van Hout-Wolters, B. H. A. M. (2007).

The gap between educational research and practice: A

literature review, symposium, and questionnaire.

Educational Research and Evaluation, 13(3), 203-220.

Chatzinotas S. and Sampson D. (2004). eMAP: Design

and Implementation of Educational Metadata

Application Profiles. In Proc. of the 4th IEEE

International Conference on Advanced Learning

Technologies ICALT 2004, Joensuu, Finland.

CoreIdeas (2014):

http://www.cirtl.net/CoreIdeas/teaching_as_research.

Duval, E. (2001). Standardized Metadata for Education: A

Status Report.

http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED466155.pdf.

Feldman, A. (2007). Validity and quality in action

research. Educational Action Research, 15(1), 21 – 32.

Fraser, B. J. (2012). Classroom learning environments:

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

244

Retrospect, context and prospect. In: Second

international handbook of science education (pp.

1191-1239). Springer Netherlands.

Furlan, R., & Martone, D. (2012). Web surveys. Statistics

in Practice, 89.

Gitlin, A., Barlow, L., Burbank, M. D., Kauchak, D., &

Stevens, T. (1999). Pre-service teachers’ thinking on

research: Implications for inquiry oriented teacher

education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 15(7),

753–770.

Goble, C., De Roure, D., & Bechhofer, S. (2013).

Accelerating scientists’ knowledge turns. In

Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and

Knowledge Management (pp. 3-25). Springer Berlin

Heidelberg.

Gravemeijer, K., & Cobb, P. (2006). Design research from

a learning design perspective. In J. van den Akker, K.

Gravemeijer, S. McKenney & N. Nieveen (Eds.),

Educational Design Research (pp. 19-51). London:

Routledge.

Gunn, H. (2014). Web-based Surveys: Changing the

Survey Process. Retrieved from First Monday

http://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1

014/935.

Harnad, S., & Brody, T. (2004). Comparing the impact of

open access (OA) vs. non-OA articles in the same

journals. D-lib Magazine, 10(6).

Hunter, J. (2006). Scientific Publication Packages - A

selective approach to the communication and archival

of scientific output, The International Journal of

Digital Curation, autumn 2006.

Imans J. (red.). (2014). Krachtig meesterschap: Een op

leren gerichte werkomgeving voor leraren in de

school. [Research oriented school culture]. Script!

Onderwijsonderzoek nr.1.

Kleinginna Jr, P. R., & Kleinginna, A. M. (1981). A

categorized list of emotion definitions, with

suggestions for a consensual definition. Motivation

and emotion, 5(4), 345-379.

Shagoury, R., & Power, B. M. (2012). Living the

questions: A guide for teacher-researchers. Stenhouse

Publishers.

Sinnema, C. Sewell, A., & Milligan, A. (2011). Evidence-

informed collaborative inquiry for improving teaching

and learning. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher

Education, 39(3), 247-261.

Taconis, R., Jong, Ch. de & Bolhuis, S.M (2007). CORF

®

:

an internet platform for supporting student teachers in

learning by inquiring teaching practices. In B. Csapo

& C. Csikos (Eds.), Developing potentials for

learning: 12th EARLI conference, 28 August- 1th

September 2007, Budapest, (pp. 457-458). Budapest.

Taconis, R., de Jong, C., Kools, Q., & Bolhuis, S. (2014).

CORF

®

: Internet ondersteuning voor (aankomend)

docenten die praktijkonderzoek willen doen. Internal

publication Eindhoven School of Education.

Trochim, W., & Donnelly, J. (2006). The Research

Knowledge Methods Base. Atomic Dog.

Vrijnsen - de Corte, M.C.W., Brok, P.J. den, Kamp,

M.J.A. & Bergen, T.C.M. (2013). Teacher research in

Dutch professional development schools: perceptions

of the actual and preferred situation in terms of the

context, process and outcomes of research. European

Journal of Teacher Education, 36(1), 3-23.

Wubbels, T., Brekelmans, M., den Brok, P., & van

Tartwijk, J. (2006). An interpersonal perspective on

classroom management in secondary classrooms in the

Netherlands. Handbook of classroom management:

Research, practice, and contemporary issues, 1161-

1191.

Yigit, T., & Ince, M. (2014). A Framework for Web-

Based Learning Object Repository in Computer

Engineering Education. Anthropologist, 17(3), 883-

893.

Zhang, Y. (2000). Using the Internet for survey research:

A case study. Journal of the American Society for

Information Science, 51(1), 57–68.

CORF®:CollectiveEducationalResearchFacility-DesignofaPlatformSupportingEducationalResearchasanIntegral

JointEffortofResearchersandTeachingProfessionals

245