Supporting Learning Groups in Online Learning Environment

Godfrey Mayende

1,2

, Andreas Prinz

1

, Ghislain Maurice N. Isabwe

1

and Paul B. Muyinda

2

1

Department of Information and Communication Technology, University of Agder, Grimstad, Norway

2

Department of Open and Distance Learning, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

Keywords: Online Learning, Learning Groups, Distance Learning, Collaborative Learning.

Abstract: In this paper, we report on the initial findings on how to effectively support learning groups in online

learning environments. Based on the idea that learning groups can enhance effective learning in online

learning environments, we used qualitative research methods to study learning groups (interviews and

observation of learning group interactions in online learning environments) and their facilitators.

Preliminary results reveal that in order to have effective learning groups you need to take care of the

following online design issues: develop comprehensive study guides, train online tutors, motivate learners

through feedback, and foster high cognitive levels of interaction through questioning, rubrics, and peer

assessment. We conclude that well thought through online learning group with appropriate questioning and

feedback from facilitators and online tutors can enhance meaningful interaction and learning.

1 INTRODUCTION

The high rate of population growth in Uganda has

increased demand for higher education. The demand

is not commensurate with the number of higher

education institutions and corresponding

infrastructure in Uganda. Distance learning can cater

for the increased demand for higher education.

Distance learning is a mode of study where students

have minimal face-to-face contact with their

facilitators; the learners learn on their own, away

from the institutions, most of the time. Distance

learning in Uganda is dominated by the first

generation model which is characterised by blending

print study materials with occasional face-to-face

sessions. Learners are given hard copy self-

instructional study materials and regularly attend

two-week face-to-face sessions at the university

twice each semester. At most times, the students

study independently from their workplaces or

homes, using the print materials. Despite using this

learning model, distance learning practitioners use

learning group activities such as group assignments

to enhance collaborative and cooperative learning. In

distance learning, learning group activities can be

achieved if learners are compelled to come together

physically or some form of ICTs are used to

virtually connect group members to learn

collaboratively.

Collaborative learning hinges on the belief that

knowledge is socially constructed although each

learner has control over his/her

own learning.

Collaborative learning is underpinned by the social

constructivist learning theory (Vygotsky, 1978). The

proliferation of ICT in teaching and learning has

created new possibilities for supporting collaborative

and cooperative learning in distance learning

(Muyinda et al., 2015). Learning groups have been

preferred for propelling interaction and learning.

Vygotsky argues that a person’s learning may be

enhanced through engagement with others. Use of

computer supported collaborative learning can offer

possibilities of students’ interactions. Because many

distance learners are working adults who are not co-

located, computer supported collaborative learning

can offer possibilities for effective online learning

groups. However, motivating and sustaining

effective student interactions is not easy to achieve.

That requires planning, coordination and

implementation of curriculum, pedagogy and

technology (Stahl et al., 2006).

In cooperative online learning, learners share a

common knowledge pool for accomplishing

individual assignments (Muyinda et al., 2015).

Learning groups have been advocated for

increasing interaction in the learning process (Curtis

and Lawson, 2001). These have been widely used in

distance learning to enhance learning. They do this

390

Mayende G., Prinz A., Maurice N. Isabwe G. and Birevu Muyinda P..

Supporting Learning Groups in Online Learning Environment.

DOI: 10.5220/0005433903900396

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 390-396

ISBN: 978-989-758-108-3

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

by giving group assignments to help in the initiation

of learning groups. However, in first generation

distance learning, the difficulty of co-locating

students comes with the difficulty of determining

participation of

each group member in the group

assignment. It is common to find group assignments

contributed to by few group members and the

remaining members attaching their names on the

assignment. This hinders meaningful interaction

which is a pre-cursor for meaningful learning. Lack

of meaningful learning is the number one cause for

high failure and dropout rates in first generation

distance learning (Aguti et al., 2009). Fifth

generation distance learning is praised for

introducing virtual interaction and collaborative or

cooperative learning amongst distance learners. It is

our intention to find out how to make students more

effective in online learning groups. We want to

propose a model for effective online learning

groups. Based on this model, a human-centred

design process can be applied to develop an

interactive system that supports effective online

learning groups.

Section 2 of this paper reviews the literature

defining and analysing collaborative learning,

interaction processes in online learning groups, and

interaction analysis in online learning environments.

In section 3, we present the research directions and

our research methods. Section 4 presents the

preliminary results of our work. Finally, the paper is

summarised in section 5.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Collaborative Learning

Collaborative learning refers to instructional

methods that encourage students to work together to

find a common solution for a given task (Ayala and

Castillo, 2008). Collaborative learning involves joint

intellectual effort by groups of students who are

mutually searching for meanings, understanding or

solutions through negotiation (Ashley, 2009; Stahl et

al., 2006). This is what should happen in effective

learning groups. This approach is learner-centred

rather than teacher-centred; views knowledge as a

social construct, facilitated by peer interaction,

evaluation and cooperation; and learning as not only

active but interactive (Hiltz and Benbunan-Fich,

1997; Vygotsky, 1978). Anderson in his online

learning framework argues that learning can happen

through student-teacher; student-student; student-

content interactions (Anderson, 2003). Stahl et al.

(2006) also asserts that learning takes place through

student-student interactions. Ludvigsen and Mørch

(2009) found out that students effectively develop

deep learning when supported by computer

supported collaborative learning. Therefore, fourth

and fifth generation distance learning can enable

student-student interaction. Careful integration of

computer supported interaction can play a big role in

increasing interaction among distance learners using

learning groups.

Collaborative learning is based on consensus

building through interaction by group members, in

contrast to competition. This can be very helpful for

distance learners, who are typically adults.

Educational Psychologists influenced by Vygotsky

(1978) claim that students working in small groups

can share and evaluate ideas, and develop their

critical thinking (Norman, 1992; Sharan and

Shaulov, 1990; Webb and Cullian, 1983; Wells et

al., 1990). Collaborative activities are essential to

encourage information sharing, knowledge

acquisition, and skill development (Collison et al.,

2000). Different technology tools have been adopted

for collaboration in distance learning. This points to

the need to systematically integrate technology into

supporting learning groups for deep and meaningful

learning.

2.2 Interaction Processes in Online

Learning Groups

Dascalu, Bodea, Lytras, De Pablos, and Burlacu

(2014) argue that to have effective discussion groups

we need to have a friendly environment where

students feel free and comfortable enough to express

their ideas. The characteristics that bring success of

groups is categorized into personal and

organizational attributes (Hew and Cheung, 2012).

Personal attributes comprise learner’s trust, learner’s

self-awareness, learner’s motivation, learner’s

commitment, and learner’s willingness to share

experiences. Organisational attributes comprise

group size, similarity of learners’ experience (age)

or status, learners’ geographical proximity, agreed

clear aims and ground rules, flexibility to tailor a

group to learners’ needs, non-hierarchical structures,

autonomy from external authorities, planning ahead,

clarity of decision making and regular review and

feedback (Hew and Cheung, 2012). Learner’s

motivation is a key attribute in encouraging

interaction in learning groups.

Use of marks to motivate students has been

widely used in online learning environments. Marks

encourage students to contribute in online discussion

SupportingLearningGroupsinOnlineLearningEnvironment

391

forums. However, Bullen (1998); Palmer, Holt, and

Bray (2008) believe that marks do not help to

develop higher order thinking skills in Bloom’s

Taxonomy. Once a student submits the mandatory

posts or comments and is certain that s/he has scored

the required marks, s/he is not obliged to contribute

any further. Online facilitators have used guidelines

of setting number of posts as a way of encouraging

students to participate in online learning groups.

However, Murphy and Coleman (2004) found that

the quality of the discussion declined when students

were forced by the course requirement to post

messages in relation to a number of posting. The

facilitator should supplement this with feedback that

mediates learning. In learner-centred approaches the

facilitators should minimally contribute in the online

learning groups. The minimum contributions should

be strategic in assisting learning. Unfortunately,

learners would prefer the facilitator to give constant

feedback. However, Arend (2009) found out that in

forums that exhibited lower level of critical thinking,

the instructors were very active in the online

discussions, sometimes responding to nearly every

student post. Jones (2007) found out that if students

are introduced to topics that interest them, they are

more likely to be motivated to contribute in the

learning groups. Asking students to peer review one

another’s work can help increase deep interaction in

online learning environments. Peer facilitation

motivated learners to contribute in online

discussions (Hew and Cheung, 2012). This is more

common in the massive open online courses

(MOOC) where class sizes are enormous and based

on the community of practice theory as is espoused

in Wenger (1998).

2.3 Interaction Analysis in Online

Learning Environment

Quantitative methods cannot be solely depended on

in analysing the quality of interactions in online

learning groups. However, they may help in trying

to create a ground for deeper content analysis by

directing you to the specific group to look at in

detail. Fugelli, Lahn, and Mørch (2013) used both

social network analysis (SNA) and content analysis

where SNA helped them to know the peripheral and

nucleus participants in the community of practice.

During the content analysis they picked peripheral

groups and nucleus groups for further study. During

an online class environment SNA can provide a

quick understanding of the status of the learning

groups. This can help give the facilitators prompt

information on status so that the facilitator can

intervene appropriately. The facilitator’s

intervention can help to assist learning or motivate

learners to interact through questioning and

feedback. However, the introduction of interaction

analysis in analysing the quality of interactions has

seen deeper understanding of the learner’s

interactions (Jordan and Henderson, 1995).

Gunawardena, Lowe, and Anderson (1997)

developed an interaction analysis model used in

collaborative learning. This model was developed to

help in assessing the critical thinking, social and

cognitive presence, problem solving, emotion

expression and knowledge construction. Interaction

analysis can help both the learners and facilitators to

improve the quality of interactions and activities

respectively. It was developed with different phases

of knowledge construction and with more emphasis

on a qualitative approach. This can easily be

achieved through learning groups since learners can

construct their own learning. Research into

interaction analysis has revealed that teachers who

do not provoke learners into the high cognitive

levels will end at the lower levels of Bloom’s

taxonomy (Gunawardena et al., 1997).

3 RESEARCH DIRECTIONS AND

METHODS

In order to answer the overall question on how to

effectively support learning groups in online

environments, we focus on three research areas:

effectiveness of learning groups, processes of

effective learning groups and tools for supporting

effective learning groups. We want to answer the

following research questions.

What are the characteristics of an effective

learning group?

How to form effective learning groups?

How can effective learning groups be

sustained in online learning environment?

What principles can guide the creation of a

model of effective online learning groups?

How can the learning group support model

measure to the quality standards of an

effective online learning group?

What tools should be used for effective online

learning groups.

These research questions will be answered

through the following research directions.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

392

3.1 Effectiveness of Learning Groups

This research direction seeks to understand the

characteristics of an effective online learning group.

This can be done keeping in mind the three sub

directions: motivation, interaction sustainability, and

interaction levels. To achieve these directions we

shall seek to understand the teaching and learning

methods that the facilitator should use to have an

effective online learning group. We shall then be

able to identify the interventions which the

facilitators should do to: motivate learner’s

interactions, sustain learner’s interactions and have

high level cognitive learner’s interactions as

mentioned in Bloom’s taxonomy (L. W. Anderson et

al., 2001).

To achieve this, we shall do theoretical studies to

get comprehensive understanding on how to

measure effectiveness of learning groups. However,

we shall further collect data from online facilitators

from the University of Agder to learn the best

practices in use for effective online learning groups.

In the light of what precedes, we shall develop

guidelines to inform the quality of learning groups.

This research direction will be aimed at answering

what is an effective learning group.

3.2 Processes of Effective Online

Learning Groups

This research direction seeks to understand the

formation and operation processes of an effective

online learning group. Effective learning groups can

be influenced at both the formational and operational

level. Therefore, we shall seek to establish the

processes that inform the formation and operation of

effective online learning groups. This will guide us

in establishing the actions taken by both the learners

and facilitators to ensure an effective online learning

group. These actions can be looked at with the

following three dimensions in mind: motivation,

sustainability and level of interaction.

To alleviate this problem, we propose to

establish the actions by stakeholders that lead to

formation and operation of effective online learning

groups. We shall follow selected courses at both the

University of Agder and Makerere University with

the aim of establishing the formational and

operational processes in effective online learning

groups. We shall use the following methods of data

collection: interview the facilitators of the selected

courses, observe the learners in both face to face and

online learning groups, collect data from learners

through both interview and questionnaires, and use

interaction analysis to establish the levels of

interactions from the data interaction logs of the

online learning groups. This will guide us to get the

actions required for both facilitators and learners for

effective online learning groups. With this

information we shall then design scenarios for the

processes for formation and operation of learning

groups for both face-to-face and online. These

scenarios will then be discussed with the learners in

a focus group discussion in order to validate it and

come up with the most comprehensive scenarios.

However, we shall also engage with the facilitators

through interviews to understand their roles in the

formation and operation of learning groups. This

will be centred on the activities the facilitator gives

in a course. By comparing with existing frameworks,

theories or models, we shall be able to suggest the

most befitting characteristics for effective learning

groups, differentiating clearly effective processes by

the learners and facilitators. This research direction

will be aimed at answering two questions: how to

form effective online learning groups and how to

keep the quality of the operation of effective online

learning groups.

3.3 Tools for Supporting Effective

Online Learning Groups in

eLearning

This research direction will seek to design a model

which will inform development of ICT based tools

for supporting effective online learning groups. The

scenarios developed in the direction above will

critically be analysed to inform the development of a

model for effective online learning groups. We shall

then develop a proof of concept (POC) interactive

system to be used in the evaluation of the model.

The human-centred design process will be applied to

design an appropriate system for effective online

learning groups. This research direction will be

aimed at answering three questions: what principles

will guide the design of tools to support effective

online learning groups, how the developed model

measure to the quality standards of an effective

online learning group and what tools should be used

for effective online learning groups.

3.4 Methods

Qualitative methods were used in the data collection

and analysis. Those consist of semi-structured

interviews and tutors´ observations of students´

activities in the Learning Management System

(LMS) for earlier courses. The respondents were

SupportingLearningGroupsinOnlineLearningEnvironment

393

Course

Design

Trained

Online

Tutor

Motivation

and

Sustaining

Interaction

High levels

of

Interaction

Peer

Assessment

based

activities

Effective Online Learning Group

purposively selected from experienced online

facilitators at the University of Agder who use

learning groups in their courses. We conducted a

one-hour interview with each of the facilitators to

find out their experiences in effectively handling

online learning groups. Each interview was

transcribed immediately and informed the researcher

in the next interview. The transcriptions were then

analysed by categorising them into themes from

which empirical meaning was derived. A similar

research approach shall be adopted in the main study

at Makerere University beginning August 2015.

Preliminary results/themes from the University of

Agder are described and discussed in the next

section.

4 PRELIMINARY RESULTS AND

DISCUSSION

These are results of a study on best practices for

effective online learning groups at the University of

Agder. These results will be used in formulating the

hypothesis that guides subsequent parts of the

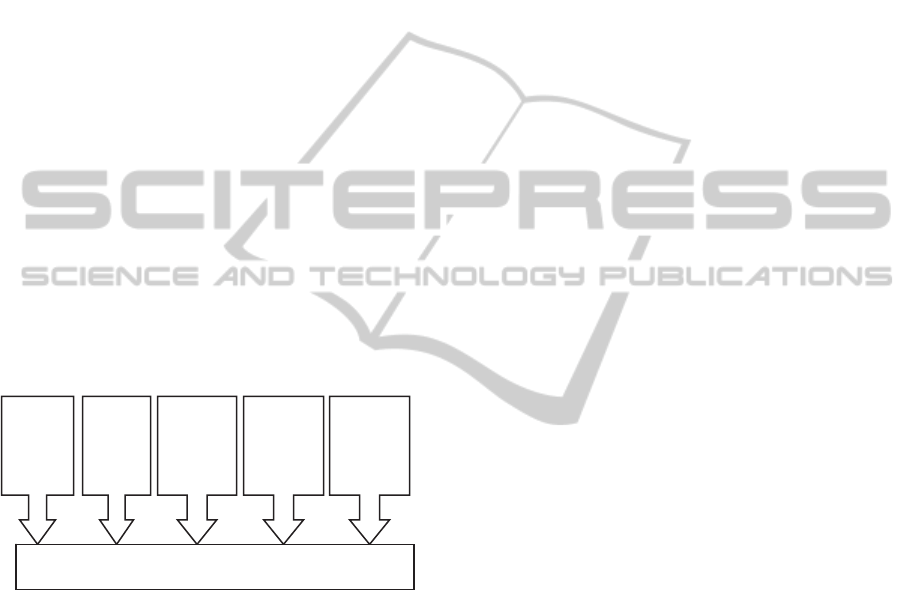

research. The findings fall into five categories

shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Salient elements in making effective learning

groups.

4.1 Course Design

The online course facilitators stressed that there is

need for comprehensive study guide and trained

online tutors in order to have an effective online

course. The necessity of trained online tutors

indicates the need for mediation of learning in online

courses. For mediation to occur there is a need to

read and give appropriate feedback of questioning

that assist learning. The study guide should include

the detailed required activities with corresponding

needed resources. These resources can range from

ICT resources, library resources, etc. The LMS

facilitators further suggested that for online tutors to

be effective each tutor should be assigned not more

than 25 learners. However, this is in contrast with

the MOOC phenomenon which emphasises that the

more knowledgeable peers will scaffold the others in

a community of practice environment (Wenger,

1998). This gives an indication about the need to

mediate, guide, scaffold and assist learning for

meaningful learning in groups. In one of our papers,

where learners were using Facebook as means to

mediate interaction and learning, learners felt that

they needed the presence of facilitator (Mayende et

al., 2014). If you chose to use tutors in a MOOC,

the cost will not be manageable since MOOCs are

free and yet online tutors have to be paid.

4.2 Trained Online Tutors

Online tutors are trained to give appropriate

feedback and questioning that assist learning groups.

Online tutor forms learning groups with five

students per group. The emphasis is put on

heterogeneous learning groups. The reason for

heterogeneous learning groups was to get different

experiential perspectives from different contexts.

This was because learners were taking a course in

global studies. However, there is need to understand

how heterogeneity affects learning. In each group

activity one student is selected by the tutor to

become the weaver of the group. A weaver is a peer

facilitator or group leader. His/her role is to direct

the discussion and summarise at the end. This can

help the group to have a sense of being together

since the peer is the one directing the discussions

and students will feel free to participate or interact.

Nevertheless, online tutors and facilitators watch

closely the interactions and can advise whenever

needed.

4.3 Motivation and Sustaining

Interactions

The online facilitators motivate learners through

allocating marks on the participation in group

activities. For LMS the number of students is

relatively small compared to MOOCs. Facilitators

give clear rubric on how marks will be assigned with

emphasis on letting the learners know the type of

interaction which will give them more marks. This is

followed during the grading where the online tutor

categorizes and reads all the contribution and awards

marks on the quality of participation. In limited

participation courses, each online tutor is allocated a

maximum of 25 students. That gives possibility to

read and grade all comments. The facilitators also

said that they motivated learners by giving feedback

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

394

which encouraged additional participation within the

groups. However, this contrasts the MOOC where

marks do not make a lot of meaning to the learners.

Motivating learners through giving feedback in

MOOC can be very challenging since the class size

is usually enormous. However, MOOCs have seen

the use of badges to motivate the learners.

4.4 High Levels of Interaction

In order to develop high order cognitive skills

through interaction, the online tutor and facilitator

apply questioning as a method of assisting learning.

Questioning is a method that assists cognitive levels

of learning although facilitators may confuse

assessment questions with assistive questions.

Assessment questions are aimed at finding out the

ability of the learner to perform without assistance,

whereas assistive questions are used to provoke the

thinking of the learner to the level s/he would not

have attained by himself/herself (Gallimore and

Tharp, 2002). The tutors are trained in how to handle

this. That systematic questioning provokes the

learner to read deep in the literature and start giving

their own opinion based on literature. They also use

feedback that is aimed at encouraging interaction

among the students. Some examples of feedback

given by the facilitator include; “that is a wonderful

contribution”, “that is a good approach”, “fantastic

knowledge”, “reading Ethan’s contribution can

reinforce your good thought”, etc. At some point

when a particular student is not participating, the

tutor will politely ask other students to find out if

s/he has some problems. Sometimes, the tutor will

follow up the missing student with a call and/or an

email. This can be very complicated in a MOOC

environment because there are very many learners.

4.5 Peer Assessment based Activities

The MOOC facilitator emphasised the use of peer

assessment as a way of motivating learners to

contribute in learning groups. The MOOC course

unit was facilitated by five facilitators and observers.

The course setting involves group work and each

group is restricted to a maximum of 5 members.

Unlike in the limited participation online courses,

groups in MOOC are created by the learners

themselves. In every module students do a group

assignment and submit as a group submission. After

that, each student is supposed to submit an

individual assignment from his/her context.

However, the students are encouraged to interact

with one another during the making of the individual

assignment. At the end of the module each student is

required to peer assess five individual assignments.

That means each student’s work is peer assessed five

times. Because of the large number of students the

facilitator is not able to effectively apply questioning

and feedback as a way of assisting learning.

However, he is able to check on some groups.

5 SUMMARY

Online learning groups can help foster meaningful

learning. This is supported by the literature on

collaborative learning and we discussed how it can

work effectively. We have presented preliminary

findings on the best practices for effective online

learning groups from the University of Agder. The

main elements to be considered include course

design, the availability of trained online tutors,

learners´ motivation and sustaining interaction,

development of high levels of interaction, and peer

assessment based activities. It was found that there is

need to provide a comprehensive study guide and

online tutors with a ratio of 25 learners per tutor.

Effective learning groups can be achieved with

appropriate intervention from the facilitators through

questioning and feedback to assist learning in the

online learning environment. This shows that

scaffolding and guidance are propellers to

meaningful learning within online learning groups.

However, there should be a mechanism to

automatically inform online facilitators whenever

the learning groups are in critical states that need

intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work reported in this paper was financed by

DELP project which is funded by the NORAD and

partial funding from ADILA Project.

Acknowledgements also go to the University of

Agder and Makerere University who are in research

partnership.

REFERENCES

Aguti, J. N., Nakibuuka, D., & Kajumbula, R. (2009).

Determinants of Student Dropout from Two External

Degree Programmes of Makerere University,

Kampala, Uganda. Malaysian Journal of Distance

Education, 11(2), 13-33.

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P. W.,

SupportingLearningGroupsinOnlineLearningEnvironment

395

Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E., Pintrich, P. R.,

Wittrock, M. C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning,

teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's

taxonomy of educational objectives, abridged edition.

White Plains, NY: Longman.

Anderson, T. (2003). Modes of Interaction in Distance

Education: Recent Developments and Research

Questions. In M. Moore & G. Anderson (Eds.),

Handbook of Distance Education. (pp. 129-144). NJ:

Erlbaum.

Arend, B. (2009). Encouraging critical thinking in online

threaded discussions. Journal of Educators Online,

6(1).

Ashley, D. (2009). A Teaching with Technology White

paper. Collaborative Tools. Retrieved on November 1,

2014 from http://www.cmu.edu/teaching/technology/

whitepapers/CollaborationTools_Jan09.pdf.

Ayala, G., & Castillo, S. (2008). Towards computational

models for mobile learning objects. Paper presented at

the Wireless, Mobile, and Ubiquitous Technology in

Education, 2008. WMUTE 2008. Fifth IEEE

International Conference on.

Bullen, M. (1998). Participation and critical thinking in

online university distance education. International

Journal of eLearning and Distance Education, 13(2),

1-32. Retrieved on November 31, 2014 from

http://www.ijede.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/2140/2

394.

Collison, G., Elbaum, B., Haavind, S., & Tinker, R.

(2000). Facilitating online learning: Effective

strategies for moderators: ERIC.

Curtis, D. D., & Lawson, M. J. (2001). Exploring

collaborative online learning. Journal of

Asynchronous learning networks, 5(1), 21-34.

Dascalu, M. I., Bodea, C. N., Lytras, M., De Pablos, P. O.,

& Burlacu, A. (2014). Improving e-learning

communities through optimal composition of

multidisciplinary learning groups. Computers in

Human Behavior, 30, 362-371. doi:

10.1016/j.chb.2013.01.022.

Fugelli, P., Lahn, L. C., & Mørch, A. I. (2013). Shared

prolepsis and intersubjectivity in open source

development: expansive grounding in distributed

work. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2013

conference on Computer supported cooperative work,

San Antonio, Texas, USA.

Gallimore, R., & Tharp, R. (2002). Teaching mind in

society: Teaching, schooling and literate discourse in

Moll (ed) Vygotsky and education: Instructional

implications and applications of socio historical

psychology Cambridge university press.

Gunawardena, C. N., Lowe, C. A., & Anderson, T. (1997).

Analysis of a global online debate and the

development of an interaction analysis model for

examining social construction of knowledge in

computer conferencing. Journal of Educational

Computing Research, 17, 397–431.

Hew, K. F., & Cheung, W. S. (2012). Student

Participation in Online Discussions: Springer.

Hiltz, S. R., & Benbunan-Fich, R. (1997). Evaluating the

importance of collaborative learning in ALN's (Vol. 1,

pp. 432-436).

Jones, L. (2007). The student-centered classroom:

Cambridge University Press.

Jordan, B., & Henderson, A. (1995). Interaction analysis:

Foundations and practice. The Journal of the learning

sciences, 4(1), 39-103.

Ludvigsen, S., & Mørch, A. (2009). Computer-supported

collaborative learning: Basic concepts, multiple

perspectives, and emerging trends, in The International

Encyclopedia of Education, 3rd Edition, edited by B.

McGaw, P. Peterson and E. Baker, Elsevier (in press).

Mayende, G., Muyinda, P. B., Isabwe, G. M. N.,

Walimbwa, M., & Siminyu, S. N. (2014). Facebook

Mediated Interaction and Learning in Distance

Learning at Makerere University Paper presented at

the 8th International Conference on e-Learning, 15 –

18 July, Lisbon, Portugal.

Murphy, E., & Coleman, E. (2004). Graduate students’

experiences of challenges in online asynchronous

discussions. Canadian Journal of Learning and

Technology, 30(2), Retrieved on November 1, 2014

from http://www.cjlt.ca/index.php/cjlt/article/view/

2128/2122.

Muyinda, P., Mayende, G., & Kizito, J. (2015).

Requirements for a Seamless Collaborative and

Cooperative MLearning System. In L.-H. Wong, M.

Milrad & M. Specht (Eds.), Seamless Learning in the

Age of Mobile Connectivity (pp. 201-222): Springer

Singapore.

Norman, K. (1992). Thinking voices: the work of the

National Oracy Project: Hodder & Stoughton.

Palmer, S., Holt, D., & Bray, S. (2008). Does the

discussion help? the impact of a formally assessed

online discussion on final student results. British

Journal of Educational Technology, 39(5), 847-858.

Doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00780.x.

Sharan, S., & Shaulov, A. (1990). Cooperative learning,

motivation to learn, and academic achievement.

Cooperative learning: Theory and research, 173-202.

Stahl, G., Koschmann, T., & Suthers, D. (2006).

Computer-supported collaborative learning: An

historical perspective. Cambridge handbook of the

learning sciences, 2006.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: the development

of higher psychological processes. Cambridge::

Harvard University Press.

Webb, N. M., & Cullian, L. K. (1983). Group interaction

and achievement in small groups: Stability over time.

American Educational Research Journal, 20(3), 411-

423.

Wells, G., Chang, G. L. M., & Maher, A. (1990). Creating

classroom communities of literate thinkers.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning,

meaning, and identity: Cambridge university press.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

396