The Role of Educational Technology in Third Space Practicum

Kathy Jordan and Jennifer Elsden-Clifton

RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia

Keywords: Educational Technologies, Third Space Theory, Practicum, Theory Practice Divide.

Abstract: There are increasing calls to improve the quality of Teacher Education by creating closer links between

universities and schools that will address the theory practice divide. In response, the School of Education at

RMIT University, Melbourne, Victoria redesigned its first year program, core courses and practicum to

align with the conceptualisation of Third Space. This article draws upon data from a larger research project;

however, the focus of this paper is to examine how educational technologies assisted in the development of

a Third Space practicum. A post-evaluation survey was completed by pre-service teachers who participated

in the redesigned course and practicum. This paper will argue that educational technology played an

important role in the Third Space practicum as it fostered collaboration, shared knowledge among

stakeholders and created expanded learning opportunities. It also highlighted the importance of relationships

in the Third Space experience.

1 INTRODUCTION

“They’ve had too much emphasis on theory and not

enough time in the classroom” Christopher Pyne,

Education Minister (The Age, 28 September, 2013).

Teacher Education has long been challenged to

conceptualise the connection between university-

based coursework and the teacher practicum and

support prospective teachers to develop theories and

practical skills for teaching (Grossman et al., 2009).

A number of approaches have been implemented to

reconceptualise relationships including; establishing

professional development schools, teaching courses

in schools, having practising teachers teach in

universities, and creating assessments that bridge

theory and practice. Such approaches support the

adoption of ‘realistic teacher education’ proposed by

Korthagen and Kessels (1999) in which theory and

practice is interconnected through a reorganised

curriculum (Zeichner, 2010). Yet, as noted by

numerous researchers, “though scholars of teacher

education periodically revise the relationship

between theory and practice, teacher education

programs struggle to redesign programmatic

structures and pedagogy to acknowledge and build

on the integrated nature of theory and practice as

well as the potentially deep interplay between

coursework and field placements" (Grossman et al

2009, p. 276). Darling-Hammond (2006) suggests

the need for models of teacher education

underpinned with stronger relationships with schools

“that press for mutual transformations of teaching

and learning to teach” (p. 3).

The notion of forming partnerships between

schools and teacher education providers has long

been advocated on the grounds that this will enable

greater connection between the coursework

delivered by providers, and the practice experience

at school sites, moving towards a shared

responsibility for teacher education. Indeed, it was

one of the key recommendations in the Top of the

Class Report (2007), and the report by the Victorian

Council of Deans of Education (Ure, Gough and

Newton, 2009). Newly implemented national

accreditation processes for teacher education in

Australia, around the provision of the practicum,

stipulate that enduring school partnerships should be

established in order to help facilitate the provision of

practice in schools (AITSL, 2009). While the

adoption of partnerships as a condition of teacher

education in Australia has been promoted (AITSL,

2009), research has shown that partnerships are

difficult to realise. Considerable time and resources

need to be outlaid and even when partnerships are

formed, there can still be a disconnect between what

is taught at the university and what is learned on site

in schools. This paper adds to the growing body of

research around the theory/practice divide in teacher

education. It explores the potential of partnerships

and the tensions between universities and schools.

This paper documents how one university

253

Jordan K. and Elsden-Clifton J..

The Role of Educational Technology in Third Space Practicum.

DOI: 10.5220/0005435402530259

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 253-259

ISBN: 978-989-758-107-6

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

formed partnerships with 14 schools and

reconceptualised the practicum experience to align

with a Third Space epistemology; where universities

and schools share responsibility for course content

and delivery. This paper begins by outlining the

literature around practicum, teacher education and

the tension between the theory practice divide. It

progresses to discuss the theory of Third Space and

how it has informed the methodology. Results of

the survey data about the teaching and learning

design features are analysed. The paper concludes

by addressing how educational technologies assisted

in the development of this Third Space.

2 THEORY PRACTICE DIVIDE

IN TEACHER EDUCATION

For well over twenty years, most reports into pre-

service teacher education in Australia typically refer

to the need to improve the quality of initial teacher

education programs, with consistent concerns about

the lack of connection between theory and practice

(Ure et al., 2009). The Top of the Class report from

the inquiry into teacher education by the House of

Representatives Standing Committee on Education

and Vocational Training (2007), argued that at the

root of this interconnection was the “current

distribution of responsibilities in teacher education”

(p.2), whereby theoretical components are typically

taught on campus by faculty and the teaching

practicum undertaken on site in schools by

practising teachers. These concerns are not confined

to Australia. In the United States, this concern has

been identified as the “central problem that has

plagued teacher education” (Zeichner, 2010, p. 89),

and Darling-Hammond (2006) describes it as the

‘Achilles heel’ of teacher education.

The teaching practicum is seen as an essential

part of becoming a teacher. It is generally

acknowledged as vital for the development of

practical skills in teaching and as a foundation of

quality teacher education (Ure et al., 2009). Yet,

how the practicum should be designed and

implemented, and the role that schools play, is a site

of contestation between pre-service teachers, teacher

mentors, schools, governments and universities.

Grove (2008) suggests that a number of issues

impact on the practicum, including the expectations

of schools, the quality of teacher mentoring and the

pre-service teachers’ scope to apply learning in the

school context. Zeichner (2010), in his often-cited

paper, is critical of the way universities approach the

practicum. Drawing on his own extensive

experience, he suggests that the teacher practicum is

often conceived as an administrative task rather than

one around the learning needs of the pre-service

teacher. This is a sentiment echoed by Darling-

Hammond (2010), who comments that:

Often, the clinical side of teacher education

has been fairly haphazard, depending on the

idiosyncrasies of loosely selected placements

with little guidance about what happens in

them and little connection to university work

(p. 11).

Zeichner (2010) comments that university staff have

few incentives to be involved in the teacher

practicum and that often it is outsourced to graduates

or retired teachers. Universities, he argues, typically

have very little involvement in the details of the

practicum, leaving these to be worked out between

pre-service teachers and teacher mentors. Zeichner

(2010) also suggests that there are issues around the

role of the teacher mentor in the practicum; mentors

he argues receive very little acknowledgement of

their efforts for supervising pre-service teachers and

little monetary reward. Another problem with the

practicum he suggests is that schools and mentors

know very little about what happens at the university

and in the coursework, and university educators

have little knowledge of what happens in schools.

With strong literature support for greater

partnerships, the School of Education at RMIT

sought to redesign their first year program to

explicitly address Zeichner’s (2010) concerns above

(explained in more detail in later sections), and to be

more aligned with the notion of Third Space.

3 THEORETICAL LENS:

THIRD SPACE THEORY

While there is general acknowledgment by policy

makers, academics, researchers and practitioners

alike, that more could be and should be done to

encourage a greater interconnection between theory

and practice in teacher education, the reasons for this

lack of connection are complex and there is no one

solution. Zeichner (2010) suggests that creating a

hybrid or Third Space could have possibilities for

bridging the boundaries between these two spaces.

To Zeichner, Third Space rejects binaries and the

notions of practitioner and academic,

knowledge/theory and practice, and integrates or

weaves them, so that an either/or perspective is

transformed into a both/also view. He explores

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

254

various examples including: bringing teachers into

university courses; bringing representations of

teacher practice into coursework, including mediated

instruction where part of a course is taught on site in

schools, or having hybrid educators where a course

is taught both at the university and on site; and/or

incorporating knowledge from communities (Taylor,

Klein, Abrams, 2014). In such spaces responsibility

for teacher education could be shared as boundaries

between practicing teachers and university

academics are blurred and there are more open lines

of communication and shared understanding

(McDonough, 2014). This paper reports on a pilot

program that created such a Third Space in an

attempt to achieve this aim.

Third Space theory is essentially used to explore

and understand the spaces ‘in between’ two or more

discourses, conceptualisations or binaries (Bhabha,

1994). Soja (1996) explains this through a triad

where Firstspace refers to the material spaces,

Secondspace encompasses mental spaces (Danaher

et al., 2003) and Thirdspace then becomes a space

where “everything comes together” (Soja, 1996, p.

56), bringing Firstspace and Secondspace together,

but also extending beyond these spaces to intermesh

the binaries that characterise the spaces. Third Space

theory is used as a methodology in a variety of

disciplines and for different purposes. For example,

it has been used to illustrate issues from colonisation

(Bhabha, 1994) and religion (Khan, 2000), to

language and literacy (Gutiérrez et al., 1997). Within

educational contexts, Moje, et al. (2004) used Third

Space theory to examine the in-between everyday

literacies (home, community, peer group) with the

literacies used within a schooling context. In their

influential paper, they summarised the three main

ways that theorists have conceptualised Third Space:

as a bridge; navigational space; and a transformative

space of cultural, social and epistemological change.

The theoretical underpinning of Third Space

influenced the way in which we positioned the

partnerships between schools and the university,

conceptualised the roles of stakeholders in addition

to guiding the design features of the course

Orientation to Teaching in which the practicum was

imbedded. This course has several design features

that were specifically used to support the

development of a Third Space and addressed

previous concerns by Zeichner (2010):

1. Course requirements and expectations were

made explicit. Pre-service teachers undertook

pre-practicum workshops to orientate them to

the course.

2. Course content was blended; delivery was

online (via an open Google Site) and face-to-

face at university and in schools.

3. Course content (workshops) was delivered

intensively on site in partner schools by school-

based tutors.

4. Course content written by practising teachers

and university staff connected theory with

practice, was practical, and gave structured

support to learning.

5. Course content made use of print media and

Web 2.0 technologies including podcasts and

social media platforms (e.g. Facebook).

6. Pre-service teachers were supported in partner

schools by being placed with a ‘buddy’, in

groups and supervised by a Teacher Mentor.

Attention now turns to the specific use of

technologies in the course design, namely the use of

a Google Site as the online platform and the

embedded use of other Web 2.0 technologies.

Ensuring that the course content was accessible to

all parties - practising teachers in partner schools,

the university faculty; and pre-service teachers - was

initially a challenge given that schools and

universities have their own preferred platforms

which with restricted access for authorised users

only. After some deliberation and experimentation

(firewalls in schools etc.) a Google Site was selected

as it would enable open access (all course materials

could be shared) and anywhere/anytime access

across operating systems. Google Sites became the

principal means for practicing teachers and

university staff to communicate with one another

about course requirements and expectations, to share

information about their own practices and specific

course materials. The Google Site designed for this

course included:

• Checklists to support learning (a self-assessment

tool using Google forms that pre-service teachers

used to demonstrate they had completed all

necessary tasks before attending tutorials)

• Podcasts to support consistency in assessment

practices (e.g. assessment advice to ensure a

consistent message across all partner schools)

• Online course materials accessible at all times

(administration, course guides, assessment

criteria sheets)

• Flipped learning activities (tasks specifically

designed to engage learners and teach core

content prior to attending the class/workshop,

including viewing and analysing YouTube

videos, viewing podcasts and simulations, and

completing audits of practice). The concept of a

TheRoleofEducationalTechnologyinThirdSpacePracticum

255

flipped-classroom, in its simplest form, involves

moving key content and concepts outside the

tutorials/lecture time, to allow for more

classroom time for “active learning, including

application of content in the form of case studies,

discussions, or simulation experiences” (See and

Conry, 2014, p. 585).

3.1 Methodology

This small-scale pilot study was conducted by the

School of Education at RMIT University, one of a

number of initial teacher education providers in

Victoria, Australia. In the past, our teacher education

programs separated the theory and practicum

components. Each year, the School organises over

2000 practicum placements in approximately 450

primary schools, 100 secondary schools and 450

early childhood settings. In 2014, the School

introduced a new model of practicum into the

Bachelor of Education (Primary) program for first

and second years. This study focuses on the

practicum course Orientation to Teaching and the

technologies appropriated to design, deliver and

support the development of a Third Space practicum

in which theory and practice were bridged. This

course was delivered in Semester 1, 2014, to first

year pre-service teachers on site in a number of

primary schools. The cohort of pre-service teachers

(270 students), were predominantly preparing to be

generalist primary school teachers, although some

were specialising in Early Childhood Education and

in Disability Studies. The majority are female

(86%), range in age from 18 to 39 years of age

(mean age of 21), and were Australian-born (89.3%)

with English as their language spoken at home

(81.3%).

A mixed methods approach was used to examine

the value of this alternate course design. A survey

instrument was produced to measure pre-service

teacher perceptions of the design features of this

course, using a four-point scale (a lot, some, a little,

not at all) and administered online via Qualtrics.

This survey and focus group data was collected from

42 (approximately 15%) pre-service teachers, who

had completed the course Orientation to Teaching,

and who volunteered to participate.

4 TEACHING AND LEARNING

DESIGN FEATURES

Survey data was analysed to reveal trends in pre-

service teachers’ perceptions of the design features

of the course. All quantitative responses were

aggregated across school/tutorial group and

examined for consistencies across themes and

responses that challenged the dominant theme/s. We

also examined the themes based on the research

aims of the study. In the first instance, this involved

analysing the features rated ‘a lot’ to reveal which

features were considered of most importance and

least importance.

Table 1: Pre-service teacher survey results on the design

features of the course Orientation to Teaching.

Course design feature:

A lot

%

Some

%

A

little

%

Not at

all

%

Teacher Mentor support 90 7 3 0

Practical focus 88 5 7 0

Structured support such

as success checklists

85 8 2 5

Connecting ideas from

class to real classrooms

81 12 7 0

Clear participant

expectations

73 20 7 0

Taught by a School-

b

ased

Tutor

71 17 10 2

Small group of pre-

service teachers at school

site

69 19 7 5

Access to materials ‘at

any time and place’

64 29 7 0

Clear learning

expectations

64 25 7 5

Podcasts 63 17 17 3

Placed with a buddy 59 17 7 17

Online materials 52 29 14 5

Pre-

p

lacement workshops

at university

52 33 10 5

Intensive mode 51 32 15 2

Workshops in schools 50 24 21 5

Connection to a textbook 38 27 33 2

As shown in Table 1, pre-service teachers

considered ‘Having Teacher Mentor support’, as the

most desired design feature of the course, with 90%

perceiving that it mattered ‘a lot’. The design

features of ‘Having a practical focus’ (88%),

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

256

‘structured support’ through success checklists,

examples (85%) and connecting ideas between

universities and classrooms (81%) also rated highly.

This provides evidence that pre-service teachers

were able to bridge the theory and practice binary.

Features that mattered less to pre-service teachers

were ‘Connection to a textbook’ (38%), despite the

textbook being very practice orientated. Explicit

reference to educational technologies tended to rate

in the mid-range. For example, ‘Being able to access

materials ‘at any time and place (online)’ rated at

64%, although interestingly, no pre-service teacher

felt it didn’t matter at all. Similarly, ‘Being able to

access podcasts of lectures 'in review' and

assessment support’ (63%), and ‘Having online

materials’ (53%) also rated in the mid-range.

Of interest, while ‘Being able to connect ideas

from class to real classrooms’ (81%) was rated

highly, ‘Having workshops in schools’ was not,

(only 50% of pre-service teachers rated it mattering

‘a lot’). This finding is of interest as the workshops

on site were designed to be the space where

connections between theory and practice were made.

This raises the question, if not at the workshops,

where did pre-service teachers make these

connections that they rated so highly? Was it the real

classroom, in discussion with the Teacher Mentor or

informally with their peers? This would be an issue

worth unpacking in future research. There was also a

vast difference in how pre-service teachers valued

support. For example, ‘Having Teacher Mentor

support’ was rated highest at 90%, but the support

from peers ‘Being placed with a buddy’ (59%) and

being in a peer group (‘Being placed with a s

mall

group of pre-service at school site

’) (69%) was not

nearly so highly rated.

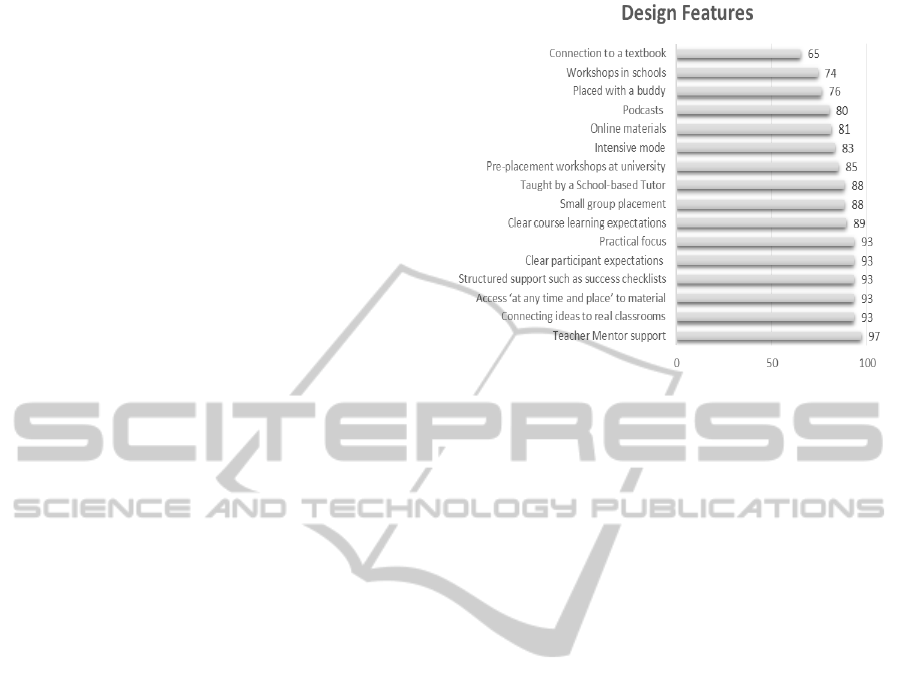

In the second instance, survey data was analysed

to gain a broader perspective of which features were

of greatest importance by adding together those

features rated as ‘a lot’ and ‘some’. Doing so reveals

a somewhat different trend. As shown in Figure 1,

‘Having Teacher Mentor support’ still rates highly,

as well as ‘Connecting ideas to real classroom’ and

‘Being placed with a small group of pre-service

teachers in one school site’. The main difference is

the role of educational technology. For instance,

being able to access materials ‘at any time and

place’ (online) is now the third most important

design (93%), see Figure 1. Structured supports such

as checklists (all online support) also increased in

importance (93%). The role of podcasts and online

material were ranked similarly in both tables.

Figure 1: Survey results combining the responses ‘a lot’

and ‘some’.

This quantitative data is supported by the qualitative

data that emerged from the open-ended questions

posed in the survey. For many of the participants in

this pilot program, the online design feature of the

course had strong appeal, with many commenting on

how this enabled them to access the course content

with ease. It was typical for comments, for example

one student stated that the online material enabled

“quick and easy access to material that I needed”.

For some pre-service teachers this access allowed

for individual learning convenience as shown in this

comment, “the online concept of this course was

very important to me and a lot of my friends also

doing the course. It meant that we had access to the

information we needed where and when best suited

us.” For others it aided their study: “with working

and studying at the same time to have resources

online made it easier to organise my studying”.

Some referred specifically to how online access

eased assessment pressures: “Being able to access

the podcasts of lectures. This made doing the

assessment tasks a lot less stressful as I knew I could

refer back to the lecture if I thought I had heard

some information that would have been helpful.”

The use of educational technologies such as a

Google Sites meant there was a shared

understanding across all schools, tutorial groups at

different schools and a central point of reference. As

one student noted: “The next most important design

feature to me was the clear checklists of exactly

what we needed to do on the O2T website. They

made life a lot easier during placement”.

Having this shared expectation and open

communication between the first space of university

and the second space of schools, was an important

TheRoleofEducationalTechnologyinThirdSpacePracticum

257

aspect of a Third Space practicum. This was

highlighted by a pre-service teacher who said:

“having clear participant expectations (students,

mentors and tutors) as open communication and set

expectation are good guidelines so that you know

what is expected from you and you can measure and

reflect on your own performance as a teacher”. This

design feature was also significant for the pre-

service teachers to succeed within the practicum, as

noted:

… having clear participant expectations with

clear course learning and structured support

[was important]. These all worked together

for me as they provided me with the support I

needed during uni and placement. Being

aware of what was expected of myself

allowed me to perform at my best in both

settings and the knowledge of the course

material, pre-readings and structured

support allowed me to come prepared to both

uni and placement.

4.1 Third Space Practicum

The aim of this study was to research the

conceptualisation of Third Space theory as a way of

improving the theory practice divide. Further, to

investigate the role of educational technologies in

assisting the development of a Third Space

practicum. One of the themes that emerged from the

pre-service teachers’ comments was the explicit

bridge of the theory practice divide. For example,

one pre-service teacher commented, “I enjoyed

seeing how the theory we were taught was instantly

reflected in teaching practices. It allowed me to be

critically aware of how other teachers incorporated

or rejected the theories and set my own opinions

accordingly”. This sentiment was also reflected by

another pre-service teacher: “I found [being on site]

really cemented a lot of things that we've been

learning about and it was really eye-opening

experience and to see it working in the workshops

and to see it in the classroom. This is really, really

valuable”. A number also commented specifically

on the practical nature of the course design as

typified in the following comment:

The most important feature to me was the

practical focus. I was a bit lost in the course

before I went on placement. It was so good to

have practical situations to apply theory rather

than always working with hypothetical

situations. I think it is really important to have

placement early on for this reason.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We were drawn to the Third Space construct for

practicum as it enabled us to make visible the

connections between schools and universities. The

notion of a Third Space, as a hybrid space, offers

possibilities for teacher education where

traditionally there have been clear boundaries

between the space occupied by theory, often taught

on campus, and the space of practicum, taught on

site in schools. For a long time, this disconnect has

been seen as one of the main areas of concern for the

quality of teacher education programs. As

demonstrated through the comments of pre-service

teachers, the Third Space practicum has the potential

to bring together the theory and practice in

meaningful ways.

Pre-service teachers while on placement inhabit a

Third Space; they neither “belong” to the school, nor

are they “at” university, thus, they are in-between

these two spaces or in a Third Space. However,

through the design features within the Third Space

practicum, they were able to interweave,

university/school, theory/practice, face-to-face/

online and learner/teacher. The quantitative and

qualitative data showed that the role of relationships

with their Teacher Mentor, buddy and being placed

with a small group of pre-service teachers at school

site were also highly valued. By creating this Third

Space, we believe that there is the potential to

expand pre-service teacher knowledge, to give them

greater opportunities to examine practice in real

settings, to reflect on practice, and possibly provide

a transformative space where new learning can

occur.

REFERENCES

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership

(AITSL). 2009. Effective and sustainable university-

school partnerships beyond determined efforts by

inspired individuals

http://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-

document-library/effective_and_sustainable_

university-school_partnerships.

Australia Parliament House of Representatives Standing

Committee on Education and Vocational Training, and

Hartsuyker, L. 2007. Top of the class: Report on the

inquiry into teacher education. House of

Representatives Publishing Unit.

Bhabha, H. 1994. The location of culture. Routledge,

London.

Danaher, P. A., Danaher, G. R., and Moriarty, B. J. 2003.

Space invaders and pedagogical innovators: Regional

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

258

educational understandings from Australian

occupational Travellers. Journal of Research in Rural

Education, vol. 18 no. 3, pp. 164-169.

Darling-Hammond, L. 2006. Constructing 21st-century

teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, vol.

57, no. 3.

Darling-Hammond, L. 2010. Teacher education and the

American future. Journal of Teacher Education, vol.

61, no. 1-2, pp. 35-47.

Grossman, P., Hammerness, K., and McDonald, M. 2009.

Redefining teacher: Re-imagining teacher education.

Teachers and teaching: Theory and practice, vol. 15,

no. 2, pp. 273-290.

Grove, K. J. 2008. Student teacher ICT use: Field

experience placements and mentor teacher influences.

Prepared for the OECD ICT and Teacher Training

Expert Meeting, Paris, France, October 2008.

Gutiérrez, K.D., Baquedano-Lopez, P., and Turner, M.G.

1997. Putting language back into language arts: When

the radical middle meets the third space. Language

Arts vol. 75, no. 5, pp. 368-378.

Hurst, D. 2013, September 28. Back to basics, The Age.

Retrieved from

http://www.theage.com.au/comment/repeat-after-

pyne-chalk-and-talk-20130927-2ujxq.html#ixzz

2gEerZIjo.

Khan, S. 2000. Muslim women: Crafting a North

American identity. University Press of Florida,

Gainesville.

Korthagen, F. A., and Kessels, J. P. 1999. Linking theory

and practice: Changing the pedagogy of teacher

education. Educational Researcher, vol. 28, no. 4, pp.

4-17.

McDonough, S. 2014. Rewriting the Script of Mentoring

Pre-Service Teachers in Third Space: Exploring

Tensions of Loyalty, Obligation and Advocacy,

Studying Teacher Education: A journal of self-study of

teacher education practices, vol. 10 no. 3, pp 210-221.

Moje, E., Ciechanowski, K., Kramer, K., Ellis, L.,

Carrillo, R., and Collazo, T. 2004. Working toward

third space in content area literacy: An examination of

everyday funds of knowledge and discourse. Reading

Research Quarterly, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 38-70.

See, S., and Conry, J. M. 2014. Flip my class! A faculty

development demonstration of a flipped classroom.

Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, vol. 6,

no. 4, pp. 585-588.

Soja, E. W. 1996. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles

and other real and imagined places. Blackwell,

Malden, MA.

Taylor, M., Klein, E. J., and Abrams, L. 2014. Tensions of

reimagining our roles as teacher educators in a third

space: Revisiting a co/autoethnography through a

faculty lens. Studying Teacher Education, vol. 10, no.

1, pp. 3-19.

Ure, C, Gough, N and Newton, R. 2009. Practicum

partnerships: Exploring models of practicum

organisation in teacher education for a standards-

based profession, Australian Policy Online,

Melbourne.

Zeichner, K. 2010. Rethinking the connections between

campus courses and field experiences in college-and

university-based teacher education. Journal of Teacher

Education, vol. 61, pp. 89-99.

TheRoleofEducationalTechnologyinThirdSpacePracticum

259