Collaborative Teaching of ERP Systems in International Context

Jānis Grabis

1

, Kurt Sandkuhl

2

and Dirk Stamer

2

1

Institute of Information Technology, Riga Technical University, Kalku 1, Riga, Latvia

2

Chair of Business Information Systems, University of Rostock, Albert-Einstein-Straße 22, Rostock, Germany

Keywords: ERP, Collaborative Teaching, ERP Internationalization, Business Process.

Abstract: ERP systems are characterized by a high degree of complexity what is challenging to replicate in the

classroom environment. However, there is a strong industry demand for students having ERP training

during their studies at universities. This paper reports a joint effort of University of Rostock and Riga

Technical University to enhance introductory ERP training by introducing an internationalization dimension

in the standard curriculum. Both universities collaborated to develop an international ERP case study as an

extension of the SAP ERP Global Bikes Incorporated case study. The training approach, study materials and

appropriate technical environment have been developed. The international ERP case study is performed at

both universities where students work collaboratively on running business processes in the SAP ERP

system. Students’ teams at each university are responsible for business process activities assigned to them

and they are jointly responsible for completing the process. The case study execution observations and

students’ evaluations suggest that the international ERP provides a good insight on the real-life challenges

associated in using the ERP systems in the international context.

1 INTRODUCTION

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems are one

of the most widely used large-scale information

systems (Shehab et al., 2004). They are used

primarily by large international companies operating

in many countries with different regulatory

requirements and regional and cultural differences

(Markus et al., 2000). Given importance of the ERP

systems, higher education establishments have

incorporated them in study programs (Hepner and

Dickson, 2013). A range of training materials has

been elaborated very often with a help of vendors of

the ERP systems. However, the traditional teaching

materials lack the international dimension and often

follow a one-user-does it all approach. As a result,

students are able to complete long-running multi-

role cross-organizational processes in a relatively

short time and ignoring permissions associated with

various roles. Therefore, they do not gain a good

understanding of the ways processes are executed in

practice. Additional, the traditional teaching

materials often focus on step-by-step instructions

reducing a need for in-depth exploration of the

features of the ERP systems and dealing with

potential pitfalls.

This paper reports a collaborative effort by

University of Rostock (UR) and Riga Technical

University (RTU) to provide ERP teaching in the

international environment. The objective of the

paper is to elaborate an international ERP teaching

case and to reflect on initial experiences in

collaborative studying of the ERP systems.

The international ERP case is used for practical

exercises in a study course devoted to enterprise

applications or business information systems. The

course is given to both computing and business

students and focuses on functional aspects of the

ERP systems. A sales and distribution process

performed by organizational units in different

countries is at the core of the case. The SAP ERP

system is used for executing the international sales

and distribution process. The case is developed as an

extension of the standard SAP training material

using the GBI case study (Magal and Word, 2012)

and students have knowledge of the standard case

prior starting the international case. This way the

international ERP is a natural continuation of

previous exercises and the students work in the

familiar environment. The other key principles used

in the design of the international ERP case are usage

of structured case execution instructions instead of

196

Grabis J., Sandkuhl K. and Stamer D..

Collaborative Teaching of ERP Systems in International Context.

DOI: 10.5220/0005464101960205

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2015), pages 196-205

ISBN: 978-989-758-096-3

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

the step-by-step type of instruction to facilitate

inductive learning (see section 3.2). Student groups

located in different countries are jointly responsible

for the case execution and a joint troubleshooting is

promoted to facilitate peer learning. The sales

process is executed in an asynchronous manner to

resemble real life business operations where partners

do not respond immediately.

The main contribution of the paper is

development of the didactical approach to studying

ERP systems in the international environment and

elaboration of a new type of template for presenting

case studies and training instructions. The didactical

approach is based on a mix of deductive and

inductive teaching approaches including

collaborative work by teams of the students in

different countries. The template for presenting

training instructions is based on using structured task

specifications rather than step-by-step guides.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on ERP studying.

The extended international ERP case including the

teaching approach is presented in Section 3. The

technical approach is described in Sections 4.

Section 5 reports initial case study execution

experiences and Section 6 concludes.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Boyle and Strong (2006) have identified skill

requirements of ERP graduates. The skills are

categorized as ERP technical knowledge, technology

management knowledge, business functional

knowledge, interpersonal skills and team skills. The

international ERP case focuses developing skills

systems design/integration, knowledge of business

functions, ability to understand the business

environment to interpret business problems, ability

to accomplish assignments, ability to be proactive,

ability to work cooperatively in a team environment.

More importantly ERP skills have direct impact on

ERP implementation success (Mohamed and

McLaren, 2009).

Hepner and Dickson (2013) provide a summary

of business processes taught using ERP-integrated

curricula and an ERP curriculum assessment. They

focus on value of ERP-integration. Hayes and

McGilsky (2007) report on introducing ERP systems

in the business core courses. They specifically

emphasize importance of developing training

curriculum and faculty competences showing that

the standard materials are a good starting point and

these can be later on elaborated for specific needs.

An ERP simulation game is one of the ways of

illustrating characteristics of ERP systems,

especially, to business students (Cronan et al., 2009).

The game focuses on comprehension of conceptual

foundations of the ERP systems. Léger (2006)

implemented a turn-based simulation game approach

for both undergraduate and graduate business

administration students focusing on information

technologies. The students were running five

national companies during this simulation, which

sell their products independently on three different

marketplaces. The affected processes were:

procurement, production and sales.

Cronan et.al. (2012) compared two different

methods — an objective measure and a self-assed

one — to measure cognitive learning effects in an

ERP simulation game. To obtain knowledge about

ERP systems and business processes a simulation

game is more appropriate than other learning types

like lab exercises or lectures as Cronan et. al.

pointed out. Theling and Loos (2005) proposed a

multi-perspective approach to teach ERP systems to

take into account that different roles were involved.

They integrated four different perspectives on ERP

systems in their curriculum like software engineer’s,

software consultant’s, business analyst’s and end-

user’s view. The hands-on experience was given by

a case study using standard learning material

provided by SAP. Monk and Lycett (2011)

described a work in progress multi-method approach

to measure the effectiveness of ERP teaching. They

combined a quantitative analysis of an experimental

simulation game using a t-test and a qualitative

analysis of interviews about the gained knowledge.

They run their simulation game both in the UK and

the US.

Dealing with complexity of ERP systems is a

major challenge in studying ERP systems. Hussey et

al. (2011) propose a methodology for facilitating

active learning so that students can attain in-depth

understanding of the ERP systems. O’Sullivan

(2011) perceives usage of ERP systems as a way of

bringing in real-world tools and experience in the

classroom. ERP training can contribute to

development of a wide range of professional skills

for engineering students (Moon et al., 2007).

International collaboration is shown be particularly

beneficial. Although modern information systems

are used in the global context, information systems

curriculum often does not follow the suite

(Pawlowski and Holtkamp, 2012). The

internationalization framework proposed in that

paper emphasizes importance of collaboration,

communication and project management to achieve

CollaborativeTeachingofERPSystemsinInternationalContext

197

curriculum internationalization objectives.

Chang et. al. (2011) investigated the influence of

post-implementation learning on ERP systems. They

used a cross-sectional mail survey including 47

companies for their quantitative research. The

number of returned questionnaires was 659. The

main finding is that post-implementation learning

has a significant influence on ERP usage including

the dimensions like decision support, work

integration and customer service. Furthermore,

Chang et.al. showed that ERP usage has also

significant effects on individual performance

including areas like individual productivity,

customer satisfaction and management control.

The literature survey provides evidence that ERP

training plays an important role in information

systems curriculum. The training has to provide a

wide range of skills and internationalization is one

of major challenges. Capturing complexity of using

and developing large scale information systems is

also important and challenging in the classroom

environment. According to our literature research

there is no cross-country collaborative case study

using an ERP system including a setting with

multiple roles and limited permissions in order to

deepen the students’ knowledge on cross-

organizational business processes. This applies also

to ERP systems taught by double loop learning and

peer learning.

3 DESCRIPTION OF THE CASE

STUDY

The international ERP studies are implemented as a

collaborative effort between Riga Technical

University and University of Rostock. The

international ERP case is designed for business

informatics and information technology students as

an introduction in ERP systems. It is based on the

standard GBI case provided (Magal and Word,

2012). The standard case is extended for application

in the international environment.

3.1 Teaching Environment

The international ERP is a part of courses devoted to

introduction to ERP systems. At RTU, the ERP

Systems course is given to master students in the

Information Technology study program. At UR, the

course is given to both Master students in Business

Informatics and students in the “Service

Management” program which leads to a Master

degree in business administration. The Information

Technology as well as Business Informatics study

programs deal with application of ICT in business

environment and the ERP systems is one of the key

aspects of using ICT at companies. The introductory

ERP courses at both universities focus on general

characteristics and functional aspects of the ERP

systems. This founding knowledge is used as a

prerequisite in related courses devoted to ERP

development and implementation of enterprise

applications.

Table 1 lists topics covered in the courses at

RTU and UR, respectively. Every topic consists of

lectures and practical exercises in the lab following

the standard GBI curriculum. The international ERP

process is executed as a part of the topic on ERP

internationalization. This topic is given using the

extended international case. It consists of an

introductory overview of international ERP,

independent work by students’ teams of

international ERP process execution and reflections

on the process execution. Further details of the

collaborative learning process are provided in

Section 4. Completion of the international ERP

process yields credits towards the final grade of the

course.

Table 1: Topics of the introductory ERP courses.

RTU UR

Enterprise business

processes

General characteristics of

enterprise applications

Data in ERP systems

Sales and distribution

process

Financial accounting

processes

Sales and financial

accounting integration

Production and inventory

management processes

ERP internationalization

Process-oriented

organizations

General characteristics of

information systems in

enterprises

ERP systems

Sales and distribution

processes

Material management

processes

Financial accounting

processes

Integration of business

processes

Electronic business in

general

e-procurement

The specific learning objectives for the international

ERP case are:

Strengthening general ERP usage skills

Strengthening knowledge of the sales and

distribution process

Ability to track the process execution progress

Improving communication skills and foreign

language skills

Business process execution in the collaborative

setting

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

198

Understanding of roles and user permissions in

ERP systems

The learning objectives relate to the required

ERP skills as identified by Boyle and Strong (2006).

The ERP usage skills and knowledge of the sales

and distribution process are strengthened by the need

to go beyond standard tasks described in the step-by-

step instructions. The process execution progress

should be tracked to ensure communication among

the distributed teams and to comply with the

reporting requirements. The student teams work

together thus improving their teamwork skills

reinforced by working in the international

environment. By using the structured case

requirements and instructions, the students also learn

about design of ERP implementation artefacts. The

technical objective of understanding roles and

permissions in the ERP systems is achieved by

limiting a number of functions each student team

can perform.

3.2 Teaching Method

From a teaching perspective, the selection of

methods and instruments started from the learning

outcomes the international case study was supposed

to establish. These learning outcomes are presented

in Section 3.1. Learning outcomes are what the

students can reliably demonstrate at the end of the

module, i.e. what can be assessed in exams or is

manifested by oral presentation or written

documentation of the students’ results.

Traditional engineering instruction usually

follows a deductive approach, which starts with

theories introduced in lectures or homework and

progresses to the applications of those theories.

Alternative teaching approaches are more inductive

and include methods, such as problem-based

learning, project-based learning or case-based

teaching {Prince and Felder, 2007). As inductive

teaching methods are found to be more effective

than traditional deductive methods for achieving a

broad range of learning outcomes (Prince and

Felder, 2006), we decided to combine deductive and

inductive approaches. Teaching in the international

case study started with a deductive part: lectures

introduced the relevant theoretical background;

homework of the students was directed to read

additional material; the material was discussed in

question-answer sessions at the beginning of the

next lecture. After the deductive part, the inductive

part followed manifested in case-based teaching (see

also Section 4.4).

When planning the teaching method, we also

took into account that in particular in ICT there is a

tendency to a competence perspective on personal

qualification, as manifested in the European e-

Competence Framework (CEN 2014). The term

competence is defined by the e-CF 3.0 as:

“Competence is a demonstrated ability to apply

knowledge, skills and attitudes for achieving

observable results.” (CEN 2014, p. 5). Typically a

distinction is made between technical, method and

social competences. The technical and method

competences for our teaching module correspond to

the learning outcomes defined in section 3.1.

However, the teaching module also has the objective

to develop social competences. Social competences

are difficult to express in “assessable” learning

outcomes but nevertheless need to be taken into

account when planning the teaching methods. For

our case, the social competences are the ability to

actively contribute to distributed and international

group work, which includes understanding that work

with partners in other locations and countries usually

cannot be solely performed by using ERP systems

but also requires communication with people and

coordination of group work and to train the ability to

coordinate problem solving in distributed teams.

In order to support the inductive part of our

teaching module, we decided to support different

learning situations: collaborative learning, peer

learning and tutoring. Collaborative learning can be

very broadly defined as "a situation in which two or

more people learn or attempt to learn something

together" (Dillenbourg 1999, p. 1). In our case, we

formed groups of students who got a joint

assignment which included initial guidelines how to

proceed. Some of the advantages attributed to

collaborative learning are, e.g., that students come to

a more complete understanding by comparing their

views with other group members, having to explain

to others requires elaboration and students with

better skills serve as promoters in the groups (Laal

and Ghodsi, 2012).

Tutoring basically means to guide the students or

group of students to the point in the learning process

at which they become independent learners.

Tutoring was provided by having a subject teacher

from the field as “stand-by” for inquiries of the

students during the course of the case study. At each

university, a tutor was available who could be

contacted by e-mail or visiting the tutor’s office.

Online-tutoring by using video-links was also

possible.

Peer learning basically is the “acquisition of

knowledge and skill through active helping and

supporting among status equals or matched

CollaborativeTeachingofERPSystemsinInternationalContext

199

companions” (Topping, 2005). We envisioned that

peer learning situations would emerge between the

collaborating groups at the two universities, i.e. that

the groups from Riga would help the corresponding

group from Rostock to understand issue and solve

problems in the case study and vice versa. Support

for peer learning was provided by offering document

sharing, joint editing platforms and communication

support for the groups.

For the above learning situations, computer

support is provided, e.g. by providing groupware

and learning management systems. The students

were made aware of these instruments and used the

computer support for peer learning and tutoring as

part of their collaborative learning.

In order to develop the social competences, we

designed the case material in a way that enforced

communication between groups in Riga and

Rostock, e.g. by including exceptions in the work

flow which could not be remedied just by using the

ERP system. Furthermore, the groups were forced to

agree on an internal way of working, i.e. we did not

define the “inner” roles and tasks of the teams. In

Rostock, we also formed teams with mixed

backgrounds, as the participants were from business

information systems (engineering-oriented) and

service management (purely business-oriented)

programs. The tutor actively focused on technical

and method support and promoted discussions

within the teams for solving communication

problems or conflicts.

3.3 Extended GBI Case

The international ERP case is developed as an

extension of the standard GBI case. It covers the

sales and distribution process starting with a

customer inquiry and finishing with customer

payment. It is assumed that GBI has outsourced

several business functions to another country. The

operations in another country are performed by a

business services provider on behalf of GBI. The

outsourcing service provider company is called GBI

BPO. GBI is responsible for the customers

relationship management and billing activities, while

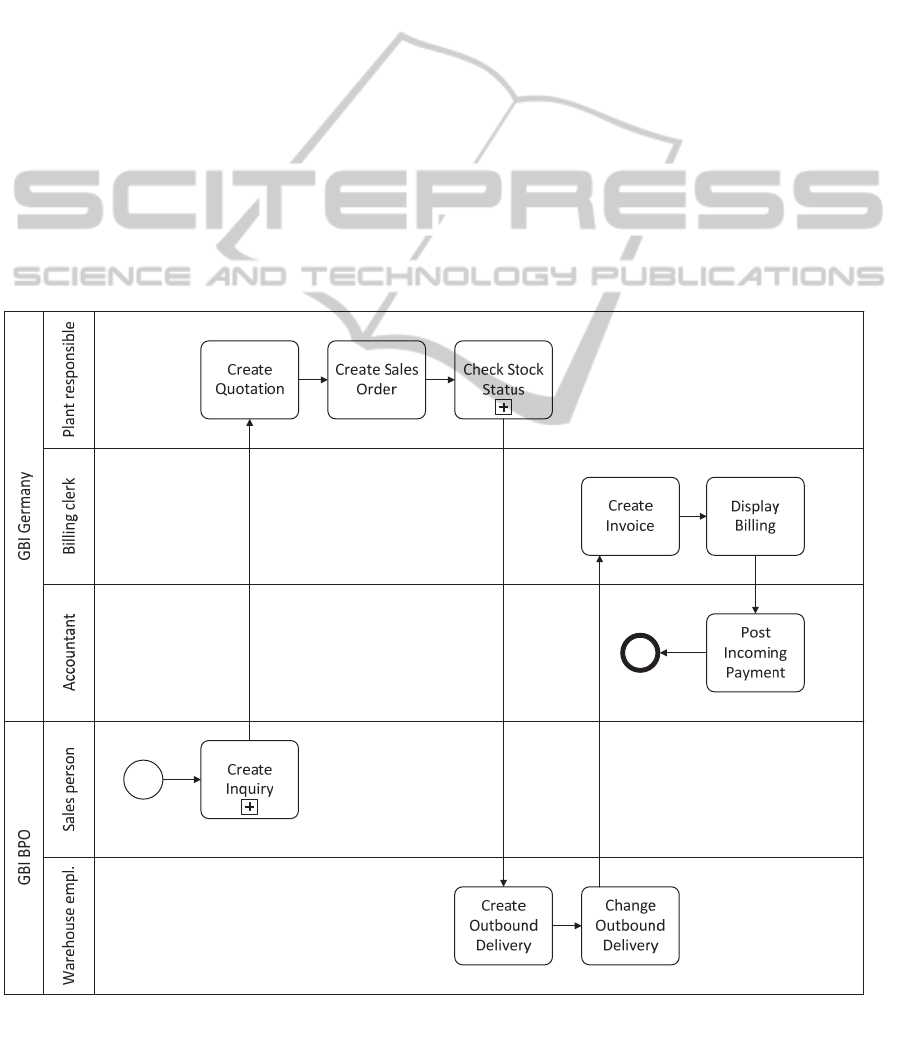

Figure 1: The international sales and distribution process.

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

200

GBI is responsible for preparing initial sales

documents and the warehousing activities. Activities

performed in one country depend upon activities

completed in other country. The process involves

Sales and Distribution (SD), Materials Management

(MM) and Financial Accounting (FI) activities.

An overview of the international ERP process is

given in Figure 1. The process is initiated by one of

the GBI customers inquiring about buying bicycles.

In the case of a new customer or changing customer

contact information, the customer master data are

updated. A new customer can only be created by the

Plat responsible but customer data also can be

changed by the Sales person. The customer also

requests GBI to issue a legally binding sales

question. During the process, employees use SAP

ERP reporting and analytic functions to analyze the

sales process. For instance, the employees evaluate

the order probability of success and check the stock

level. Once the customer has accepted the quotation,

a sales order is created and the shipping and billing

activities are initiated. The Warehouse employee

creates an outbound delivery document and

indicating the materials pick-up data in this

document. The Billing clerk creates an invoice for

the materials delivered, and the Accountant settles

the invoice by posting incoming payments. If

customers request products, which are currently not

available in the stock, than the procurement

processes should be invoked. The procurement

operations are performed by GBI BPO.

4 TECHNICAL APPROACH

In order to achieve learning outcomes, the standard

GBI training instructions were extended and

restructured, alternative variants of ERP setup were

identified and appropriate user rules were created in

the ERP system.

4.1 Design of Instructions

Given that the students already have had an

introduction into working with the ERP system

following the standard GBI guidelines, the

international GBI instructions are created to

resemble ERP implementation specification

documents rather than the step-by-step instructions.

That is intended to promote self-learning and deeper

understanding. At the same time, the students always

can consult the standard GBI training materials.

In a fashion similar to ERP specification

documents, each process activity defined using its

objective, role involved, tasks to be performed and

input data.

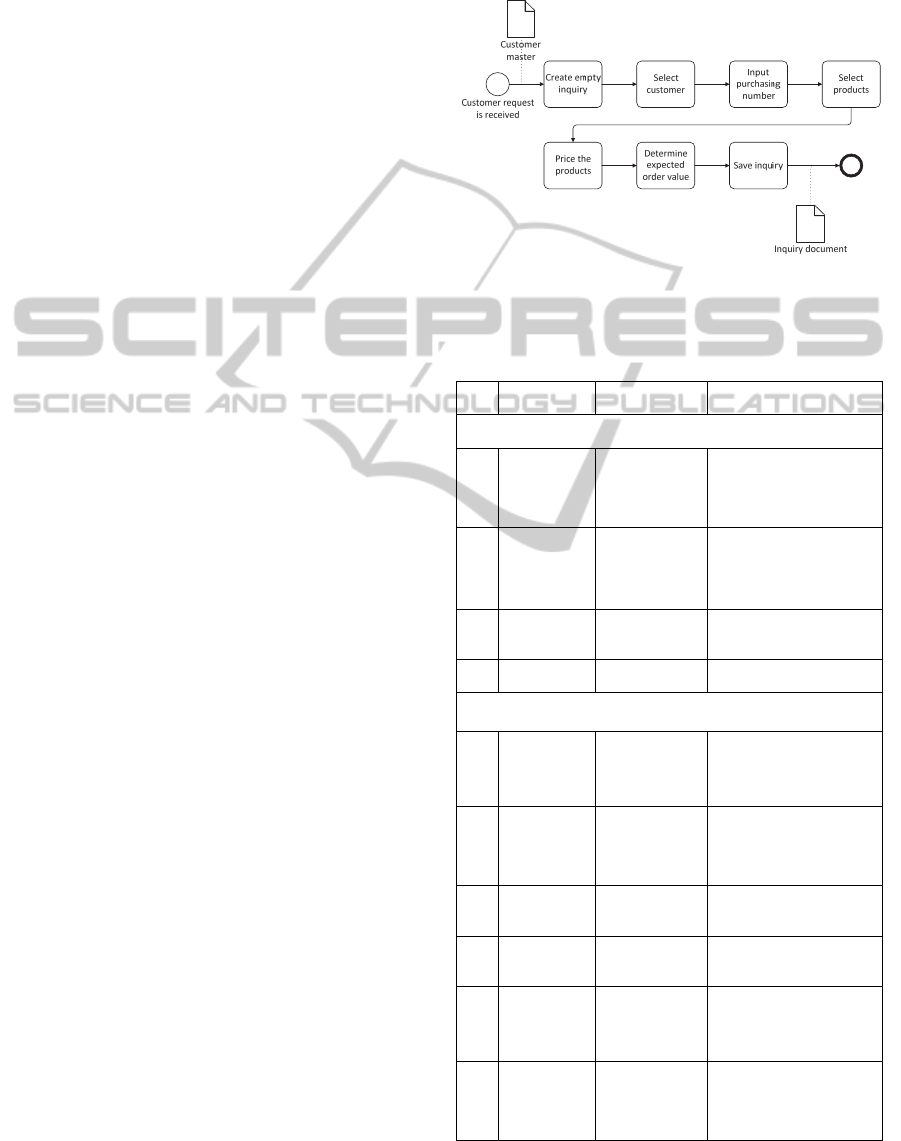

Fragments of the instructions given to the

students are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2.

Figure 2: Elaboration of tasks of the Create Inquiry

activity.

Table 2: Input data for performing tasks of the Create

Inquiry activity.

Nr Data item Value Description

Task 1

1 Inquiry

type

IN A classification that

distinguishes between

different types of

sales document.

2 Sales

organizati

on

US East An organizational unit

responsible for the

sale of certain

products or services.

3 Distributio

n channel

WH

4 Division Bicycles

Tasks 2, 3, 4

5 Customer <customer> Customer from the

initial data of the

assignment

6 PO

number

<any string> Number that the

customer uses to

uniquely identify a

purchasing document

7 PO day <today’s

date>

8 Valid from <today’s

date>

The date from which

the inquiry is valid.

9 Valid to <today’s

date + 30

days>

The date till which the

inquiry is valid.

10 Inquiry

items

<product

name>

<quantity>

Product name and

quantity from the

initial data of the

assignment

CollaborativeTeachingofERPSystemsinInternationalContext

201

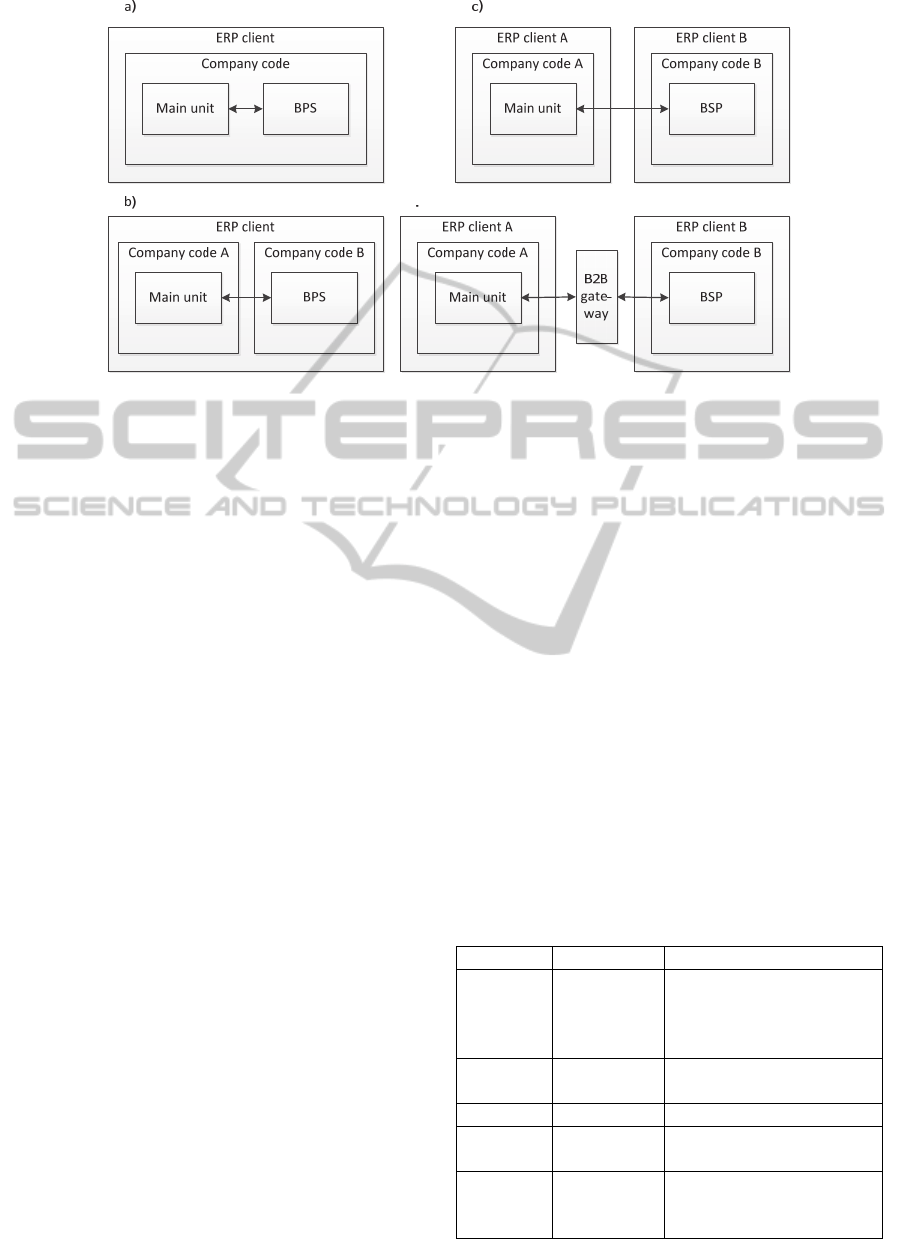

Figure 3: Integration scenarios.

These fragments refer to the Create Inquiry activity

of the Sales process. Figure 2 shows individual tasks

to be performed within this activity. For instance,

the customer information should be provided to

create an inquiry. Meaning and purpose of these

tasks are explained in the instructions. However, the

students are left to their own devices to choose

appropriate features of the ERP system to perform

the task. Table 2 provides the relevant input data

values to perform the tasks.

A template for reporting the case execution

results is also developed. It defines the main

outcomes for every step of the business process to be

reported.

4.2 ERP Setup

The ERP setup should enable execution of the

international sales process by providing integration

between teams studying at different universities.

Four integration scenarios are identified in Figure 3.

The simplest scenario (a) assumes that both

universities use the same ERP client and both the

main unit and BSP use the same company code. This

scenario implies that the identical configuration is

used and there is no need establishing an

information integration link. The single client two

company codes scenario (b) implies that both

companies might have different configuration

allowing to represent specific localization

requirements while application integration is not

necessary. The remaining two scenarios (c) and (d)

include application integration and most closely

resemble real-life execution of cross-enterprise

business processes.

Currently, the simplest scenario of integration is

used implying that both universities use the same

ERP client and work within a single company code

though with limited permissions to execute certain

tasks as described in the next section.

4.3 Role Setup

Every university involved in the case represents one

of the companies (i.e., GBI or GBI BPO). Every

company is responsible for a certain list of activities,

and these activities are performed by certain role in

the company (Table 3).

To delimitate the roles, two composite SAP ERP

roles are create. The composite SAP ERP role

SAP_GBI_SD_MAIN is assigned to GBI and the

composite SAP ERP role SAP_GBI_SD_BPO is

assigned to GBI BPO. Thus, every company can

perform only activities assigned to their composite

Table 3. Assignment of the roles between GBI and GBI

BPO.

Company Role Activity

GBI Plant rep.

Create new customer

Create quotation

Create sales order

Check stock status

Billing

Clerk

Create invoice

Accountant Post incoming payment

GBI BPO Sales

person

Create inquiry

Warehouse

Emp.

Create outbound delivery

Change outbound delivery

Procurement

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

202

role (e.g., Create inquiry is available only to GBI

BPO). There is no separation of roles within the

company (e.g., Plat representative and Billing clerk

use the same composite role SAP_GBI_SD_MAIN).

4.4 Collaborative Learning Process

The international ERP collaborative learning takes

place in three stages: 1) kick-off; 2) process

execution; and 3) evaluation. During the kick-off

phase, an introductory lecture on international ERP

is given, teams of students are formed and individual

assignment is given to the teams. The introductory

lecture gives an overview of the case study and

explains the collaborative learning process.

Students organize team of 3-4 students at both

universities. The teams are randomly paired together

and they exchange the contact information. The

individual assignment is given to each pair of the

teams. The individual assignments represent three

different customer inquiries and it includes cases of

a new customer and out-of-stock situations.

Execution of fulfillment processes is initiated by

GBI BPO and subsequently every team has 2

working days for completing its activities.

During the evaluation phase, the teams finalize the

process execution report and fill out a questionnaire

providing their feedback on the assignment.

5 OBSERVATIONS

The international ERP assignment was used in the

study process in Fall of 2014. 46 students organized

in 7 teams and every university participated in the

exercise. All 7 pairs of the team were able to

complete the process using data from at least two

initial customer inquiries though 3 teams were not

able to complete the process using data from one

initial customer inquiry because of incorrectly setup

master data or lack of coordination in inventory

replenishment.

The learning experience is evaluated by

summarizing responses from the questionnaire

(Table 4). The students mostly agree with statements

from the questionnaire. Several questions indicate

that the international ERP exercise was more

engaging led to better understanding of the SAP

ERP systems and the sales process. However, a

significant number of students indicate that having

specific roles did not improve their understanding of

the sales process execution in the ERP system. The

students stated that actions of the other team were

not sufficiently transparent. This issue could be

resolved by having the team to switch their roles.

There is also a significant spread of options

concerning the improvement of problem-solving

skills. On several occasions troubleshooting was

done remotely by the instructors. It is suggested that

it should be done jointly by the instructors and the

students’ team working together. Not all team

Table 4: The surveying results as a percentage of all answers.

Question Strongly Agree Agree Disagree Strongly Disagree

International ERP was a more interesting way of studying

than traditional exercises

36 42 19 3

Completing International ERP exercises was more complex

than completing the standard GBI exercises

46 43 11 0

Completing International ERP exercises required more in-

depth understanding of SAP ERP than completing the

standard GBI exercises

43 46 9 3

Completing International ERP exercises improved my

understanding of SAP ERP system

39 39 11 11

Having specific roles in the process execution improves

understanding of the way enterprise applications work.

36 33 19 11

Communication with your other teams was positive 28 47 19 6

International ERP improved my collaboration and problem-

solving skills.

17 47 25 11

International ERP consumed more time than I expected. 78 14 8

We needed to communicate with the other team too often 31 42 19 8

We needed to seek outside assistance (e.g., from instructor)

too often.

28 44 17 11

CollaborativeTeachingofERPSystemsinInternationalContext

203

interacted smoothly and this issue could be resolved

by organizing an initial virtual get-together for the

team members from all universities so that they can

discuss their background and studying approach.

A number of potential improvements in the

instructions and organization of the collaborative

learning process were also identified to reduce the

need for frequent outside assistance from the

instructors.

The learning objectives stated in Section 3 were

achieved. The knowledge of the sales process was

improved by resolving different exceptional

situations not considered in the standard GBI case.

The teams were able to track the process execution

and to exchange the necessary process execution

data as well as to submit the final report. The

students had very intense exchanges and jointly

worked on problem solving. They experienced

significant peer pressure to complete their activities

on time and they approached that very dutifully. The

cases of peer learning were observed both within the

team and among team in both universities. The

students also experience restrictions imposed by

having different roles in the SAP ERP system.

In general, the mix between deductive and

inductive teaching methods proved suitable for our

teaching module and the international ERP case

study. A small part of the lectures was a repetition of

content in information systems, ERP systems and

process-oriented organizations that already was part

of earlier courses. Most of the lectures were

dedicated to prepare case study work.

It is difficult to assess what individual progress

and competence development the different students

made. Here, we only can rely on the results of the

assignments and exams. We also performed the

international case study in autumn 2013. In 2013,

the participation in the case study was not

mandatory for in Rostock from MSc service

management, i.e. they were allowed to participate in

the e-Business module without the case study. When

comparing the exam results between those students

participating in the case study and those not

participating, the results for the participating ones

were much better in the ERP part. This is not

surprising; nevertheless it indicates a certain value of

the case study for learning success.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The international ERP provides a realistic

representation of business process execution using

ERP systems in the international environment and

the students recognized the value of having this kind

of exercise. At the same time several areas of

improvement have been identified. The objective of

promoting collaborative problem-solving was only

partially achieved and additional effort should be

devoted to establishing initial cohesion between

team at different universities. The joint

troubleshooting with the instructors is also

important. The students need to have an initial

exposure to the SAP ERP system and going through

the standard GBI curriculum first is essential for

successful completion of the international ERP.

From the technical perspective, other ERP

integration scenarios should be considered as they

provide a more realistic representation of the way

ERP systems are used by different companies.

Exposing differences of ERP configurations used in

different counties is also an important aspect for

further elaboration.

Using a common e-learning platform is also

considered for future activities because current e-

learning systems used at both universities are not

compatible and even though the same information

was distributed to the students it was presented

differently and there were some information

availability gaps. This is the general limitation of

many e-learning platforms that they are not geared

towards cross-university collaboration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work presented in this paper was supported

within the projects “KOSMOS (Konstruktion und

Organisation eines Studiums in Offenen Systemen)”

and “Studium Optimum” funded by the BMBF

(Federal Ministry of Education and Research,

Germany) and the European Social Funds of the

European Union.

REFERENCES

Boyle, T. A., & Strong, S. E., 2006. Skill requirements of

ERP graduates. Journal of Information Systems

Education, 17(4), 403-412.

CEN, 2014. European e-Competence Framework 3.0: A

common European Framework for ICT Professionals

in all industry sectors. CWA 16234:2014 Part 1.

Chang, H.H., Chou, H. W., Yin, C. P., Lin, C. I., 2011.

ERP post-implementation learning, ERP usage and

individual performance impact. PACIS 2011

Proceedings. 35.

Cronan, T.P., Douglas, D.E, Schmidt, P., Alnuaimi., O.,

2009. ERP Simulation Game; Learning and Attitudes

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

204

toward SAP Samples of Company „First Time Hires.

Technical Report, University of Arkansas.

Cronan, T. P., Leger, P. M., Robert, J., G. Babin, and P.

Charland, 2012. Comparing Objective Measures and

Perceptions of Cognitive Learning in an ERP

Simulation Game: A Research Note. Simulation &

Gaming, 43, 4, 461–480.

Dillenbourg, P., 1999. What do you mean by collaborative

learning? Collaborative-learning: Cognitive and

Computational Approaches, 1-19.

Hayes, G., McGilsky, D.E., 2007. Integrating an ERP

System into a BSBA Curriculum at Central Michigan

University. International Journal of Quality and

Productivity Management, 7, 1, 12-17.

Hepner, M., Dickson, W., 2013. The value of ERP

curriculum integration: Perspectives from the research.

Journal of Information Systems Education, 24, 4, 309-

326.

Hussey, M., Wu, B., Xu, X., 2011. Open and Closed

Practicals for Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP)

Learning. In Software Industry-Oriented Education

Practices and Curriculum Development: Experiences

and Lessons, 138-152.

Laal, M., Ghodsi, S., 2012. Benefits of collaborative

learning, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences,

31, 486-490.

Leger, P. M., 2006. Using a simulation game approach to

teach ERP concepts. Journal of Information Systems

Education, 17, 4, 441-447.

Magal, S.R., Word, J., 2012. Integrated Business

Processes with ERP Systems. Wiley, New York.

Markus, M.L., Tanis, C. & Van Fenema, P.C. 2000,

Multisite ERP implementations. Communications of

the ACM, 43, 4, 42-46.

S. Mohamed, T. S. McLaren, Probing the Gaps between

ERP Education and ERP Implementation Success

Factors, AIS Transactions on Enterprise Systems 1

(2009) 1, 8-14.

E. Monk and M. Lycett, “Using a Computer Business

Simulation to Measure Effectiveness of Enterprise

Resource Planning Education on Business Process

Comprehension,” 2011.

Moon, Y.B., Chaparro, T.S., Heras, A.D. 2007, "Teaching

professional skills to engineering students with

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP): An international

project", International Journal of Engineering

Education, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 759-771.

Pawlowski J.M., Holtkamp, P., 2012. Towards an

internationalization of the information systems

curriculum. MKWI 2012 - Multiconference Business

Information Systems, 437-449.

Prince, M. J., Felder, R. M. , 2006. Inductive Teaching

and Learning Methods: Definitions, Comparisons, and

Research Bases. Journal of Engineering Education, 95,

123–138.

Prince, M., Felder, R., 2007. The many faces of inductive

teaching and learning. Journal of College Science

Teaching, 36, 5, 14.

O'Sullivan, J., 2011."Does using real world tools in

academia make students better prepared to enter the

workforce as compared to a toy type simulation

product? A look at ERP in academia, does using this

real world tool make a difference to industry?, IMSCI

2011 - 5th International Multi-Conference on Society,

Cybernetics and Informatics, Proceedings, 102.

Shehab, E.M., M.W. Sharp, L. Supramaniam and T.A.

Spedding, 2004. Enterprise resource planning An

integrative review. Business Process Management

Journal 10, 4, 359-386.

Theling, T., Loos, P., 2005. Teaching ERP Systems by a

multiperspective approach. Association for

Information Systems - 11th Americas Conference on

Information Systems, AMCIS 2005: A Conference on

a Human Scale 3, 1043-1054.

Topping, K. J., 2005. Trends in peer learning. Educational

Psychology, 25, 6, 631-645.

CollaborativeTeachingofERPSystemsinInternationalContext

205