Eudaimonia in Human Factors Research and Practice

Foundations and Conceptual Framework Applied to Older Adult Populations

Katie Seaborn

1

, Peter Pennefather

2

and Deborah I. Fels

1,3

1

Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, University of Toronto, 5 King’s College Road, Toronto, Canada

2

Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, 144 College St. Toronto, Canada

3

Ted Rogers School of Management, Ryerson University, 350 Victoria Street, Toronto, Canada

Keywords: Human Factors, Eudaimonics, Hedonomics, Well-being, Quality of Life, Eudaimonia, Hedonia.

Abstract: Well-being/quality of life has emerged as a strand of inquiry in human factors research that has expanded

the field’s reach to matters beyond fit, functionality and usability. This effort has been spearheaded by

“hedonomics,” a human factors conceptualization of well-being that reflects the philosophical notion of

hedonia, traditionally defined as pleasure. However, recent work in the psychology of well-being has shown

that hedonia constitutes only one facet of well-being. In light of this, the concept of “eudaimonics” as a

complement to hedonomics is introduced. First, these concepts are positioned relative to their counterparts

in philosophy: where hedonomics is characterized by pleasure and avoidance of pain (hedonia),

eudaimonics is characterized by flourishing and personal excellence (eudaimonia). Following this, a

working conceptual framework for eudaimonics that is informed by the psychological literature is

presented. An expansion of the hedonomics model of design priority hierarchy is offered. Applications to

the domains of ageing well and technologies for older populations are proposed. Directions for future work,

including the adoption and modification of psychology instruments for human factors research, is discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Human factors/ergonomics (HF/E; hereafter “human

factors”), a multidisciplinary domain of research and

practice that looks at the fit between people and

systems, is typically concerned with three main

issues: safety, productivity, and prevention of error

(Meister 1999; Vicente 2004). However, a growing

number of researchers and practitioners have begun

to consider other factors that affect fit, including

satisfaction and motivation for life activities and the

impact those activities have on overall well-being.

A relatively new domain of inquiry called

“hedonomics,” which takes its name from the Greek

root of “hedonia,” has attempted to tackle the

intersection of well-being, people and systems.

Hedonomics is explicitly concerned with positive

and pleasurable interactions between people and

systems (Hancock et al., 2005; Helander and Tham,

2003). However, a review of the philosophical

foundations and recent work on psychological

constructs of well-being show that hedonomics is

limited by its focus. This combined with recent

insights on the need for a well-rounded perspective

of well-being, e.g. for older adults and mobility

(Nordbakke and Schwanen, 2014), argue for an

expanded view of well-being in human factors that

addresses well-being factors that are conceptually

outside the purview of hedonomics.

In this paper, “eudaimonics” is introduced as a

complementary concept to hedonomics and potential

area of research and practice that is (a) proposed by

the philosophical underpinnings of well-being, and

(b) supported by established psychological work on

well-being. A preliminary conceptual framework for

eudaimonics as well as an expansion of the

hedonomics model of design priority is proposed.

The main contribution of this paper is therefore an

informed expansion of well-being in human factors

from philosophical and psychological perspectives,

particularly with respect to the ageing process.

2 CONCEPTUAL OVERVIEW

In the last century, interest in well-being has taken

root within many disciplines, including health,

gerontology, philosophy, and psychology. A wealth

of terms and definitions abounds within and among

these domains. In psychology, for instance, well-

Seaborn K., Pennefather P. and I. Fels D..

Eudaimonia in Human Factors Research and Practice - Foundations and Conceptual Framework Applied to Older Adult Populations.

DOI: 10.5220/0005473003130318

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (SocialICT-2015),

pages 313-318

ISBN: 978-989-758-102-1

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

being has been defined as (a) “optimal psychological

experience and functioning” (Deci and Ryan, 2008,

p.1), (b) happiness, positive affect, and lack of

negative affect (Bradburn, 1969), and (c) life

satisfaction (Ryff, 1989), among many others. To

compare with a perspective from another domain:

the World Health Organization defines well-being as

“individuals’ perception of their position in life in

the context of the culture and value systems in which

they live and in relation to their goals, expectations,

standards and concerns” (World Health

Organization, 1997, p.1). Likewise, the constructs

that make up conceptualizations of well-being and

the measures used to assess well-being are equally

varied.

This diversity of domains and definitions provide

several valid options on which to base a conceptual

understanding of well-being in human factors. Given

the ties human factors has to psychology and the

effort undertaken by psychologists to achieve a

coherent, rich, measurable conceptualization of well-

being, as well as overlap between the psychological

literature and conceptualizations of hedonomics, we

have chosen to focus on the psychological literature.

2.1 Philosophical Foundations

Well-being can be traced to Hellenic philosophy on

what constitutes “the good life” (Ryan and Deci,

2001; Keyes et al., 2002; Ryff, 1989).

Disagreements among philosophers gave rise to two

perspectives on well-being: the Aristippian

“hedonia” as the pursuit of pleasure; and the

Aristotelian “eudaimonia” as the pursuit of

excellence (Deci anf Ryan, 2008; Ryan and Deci,

2001). Recently, an alternative to the Aristippian

view has been proposed: “hedonic utility,” a view

based on the utilitarian philosophy of 18

th

century

philosopher Jeremy Bentham (Sirgy, 2012; Graham,

2012, p.33). Regardless, the essence of each position

is that eudaimonia focuses on virtue and hedonia

focuses on pleasure.

2.2 Psychological Foundations

As in the time of the early Greek philosophers,

debate about what well-being is—how it should be

defined, what it constitutes, how it can be measured,

and what to call it—continues. A perusal through the

literature will reveal several terms that are

sometimes used to refer to the same or different

constructs. For example, in his recent text on the

psychology of well-being, Sirgy (2012) argues for

three constructs of well-being: “hedonic well-being”

(which constitutes happiness and affect, components

that others, have attributed to subjective well-being),

“life satisfaction” (which others consider to be a

component of subjective well-being, or SWB), and

“eudaimonia” (which encompasses psychological

well-being, or PWB, and flourishing), while also

sometimes using “subjective well-being” to refer to

all aspects of well-being. In contrast, Waterman et

al., (2010) argue that “hedonic well-being” can be

used to refer to SWB, where both refer to the same

concept. Here, we will review the literature and

endeavour towards a consensus in terminology and

concepts using the latest empirical research on how

well-being constructs can be distinguished.

2.2.1 Subjective Well-being and Hedonia

Subjective well-being (SWB) has a lengthy history

within psychology. It is important to note that while

some (e.g. Sirgy) may use the term to refer to well-

being as a whole from a psychological perspective,

and it can be confused as a reference to subjective

approaches to assessing well-being, SWB is a

standalone concept with empirical backing.

Historically, SWB has been defined as an

individual’s subjective level of happiness, comprised

of and measured through three components: positive

affect, a lack of negative affect, and life satisfaction

(Diener et al., 1999; Diener, 1984). Notably,

researchers in this area commonly use the term

“happiness” to refer to SWB (Deci and Ryan, 2008).

A new view of SWB has been developing within

the past two decades: Kahneman, Diener and

Schwartz’s (1999) conceptualization of SWB as a

hedonic construct. In this view, SWB as “happiness”

is analogous to presence of pleasure and absence of

suffering. However, a hedonic view of SWB creates

a problem for the inclusion of life satisfaction as a

component of well-being, because life satisfaction

involves conscious appraisal of one’s position in

life, a process that falls under the purview of

eudaimonia (Deci and Ryan, 2008). In sections 2.2.3

and 2.2.4, we discuss how this problem may be

resolved through a unified model of well-being

based on recent empirical work.

2.2.2 Psychological Well-being and

Eudaimonia

Research on psychological well-being (PWB) has

only gained stead in the last two decades (Deci and

Ryan, 2008). It is important to note that the term

does not merely refer to well-being from a

psychological perspective, and could instead be

better understood as “cognitive” well-being, where

knowledge of one’s well-being requires cognition:

self-awareness and conscious thought processes

about the self and one’s impact on the self and the

world. Additionally, PWB (as a psychological

construct) has been earlier and more explicitly tied

to eudaimonia (as its philosophical foundation) in

the literature than SWB to hedonia; further, some

have argued that PWB and eudaimonia should not

be conflated. We will attempt to reconcile these

differing outlooks while working towards a unified

view of this aspect of well-being.

Waterman (1993) introduced the notion of

eudaimonia as an essential quality of well-being.

Drawing from early philosophy, Waterman proposed

that eudaimonia is self-realization: a process of

fulfilment characterized by personal expressiveness

(PE) as one moves closer to one’s true self, or

“daimon.” A truly eudaimonic process meets six

criteria: deep understanding, unusually good fit with

the activity, feeling alive, feeling fulfilled, feeling

that the activity is “meant to be done,” and feeling

that one is truly being oneself (Waterman, 1990).

Waterman makes explicit ties to intrinsic motivation

(Deci, 1971), flow theory (Csikszentmihalyi, 1991),

and self-actualization (Maslow, 1962).

Ryff (1989) introduced the concept of

psychological well-being (PWB) as a multi-

dimensional construct distinct from SWB. She

developed and then validated with colleagues (Ryff

and Keyes, 1995) six dimensions of PWB:

autonomy (personal will to action), environmental

mastery, personal growth, positive relations with

others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. More

recently, Ryff and Singer (2008) performed a close

reading of Aristotle’s eudaimonia (from

Nichomachean Ethics) and discussed how it relates

(and does not) to PWB. Even so, there is some

contention among scholars, particularly Waterman

(2008), regarding the validity of using PWB alone to

characterize eudaimonia.

In their review, Deci and Ryan (2008) posit two

central differences between Ryff and Waterman’s

conceptions of eudaimonic well-being (EWB): one,

that Ryff’s PWB is about an individual’s global

well-being, whereas Waterman’s PE is specific to an

activity; and two, that Ryff’s PWB is content-

specific, e.g. the environment, relationships, etc.,

whereas Waterman’s PE is content-free.

More recently, Ryan and Deci (2001) have

argued that their self-determination theory (SDT)

underpins and gives rise to eudaimonia. SDT (Ryan

and Deci, 2000) comprises three basic psychological

needs: autonomy (also an aspect of Ryff’s PWB),

relatedness (again, an aspect of Ryff’s PWB), and

competence. They posit a number of differences

between SDT and PWB. For instance, SDT nurtures

EWB while PWB describes it. Further, SDT is

thought to nurture both SWB and EWB.

2.2.3 Life Satisfaction

Recent large sample studies that employed factor

analysis have shown that hedonia and eudaimonia

are related but distinct concepts (Proctor et al., 2014;

Huta and Ryan, 2010). However, the results of these

studies also suggest that life satisfaction, generally

considered a component of SWB (Linley et al.,

2009), is a distinct concept that may be determined

or mediated by hedonic and eudaimonic well-being

together. This provides some empirical support for

the notion that SWB cannot be considered entirely

hedonic; however, whether this is due to the

cognition involved in assessing one’s own life

satisfaction or some other reasons(s) is unknown.

2.2.4 Synthesis

The above overview presents an emerging picture of

how psychological conceptualizations of well-being

and philosophical standpoints on well-being can

mesh. Psychological research involving large sample

studies using factor analysis have shown that SWB

and PWB are distinct but related concepts (Linley et

al., 2009; Keyes et al., 2002). From a philosophical

standpoint, researchers tend to align SWB with

hedonia and PWB with eudaimonia (Waterman et

al., 2010), although some contention remains (Deci

and Ryan, 2008; Ryan and Deci, 2001) and

conceptual relatedness, if not overlap, almost

certainly exists. In any case, a growing area of

empirical work points to the need for a well-rounded

view of well-being that incorporates hedonic and

eudaimonic qualities (Huta, 2013; Nordbakke and

Schwanen, 2014).

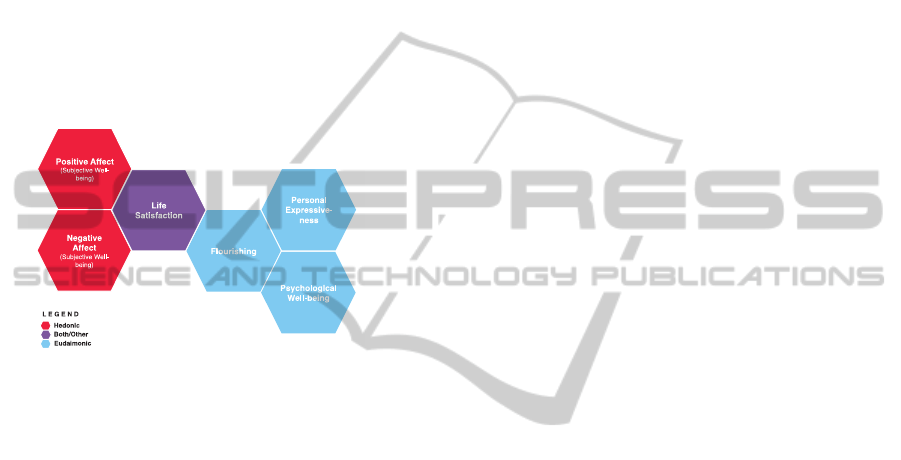

A working model that synthesizes our conceptual

overview can be found in Figure 1. We use this

model to express a conceptual understanding of

hedonomics that is based on relevant, established

philosophical and psychological concepts, and

further propose a complementary domain that we are

calling “eudaimonics.”

2.3 Hedonomics

Hedonomics as an area of research and practice was

first proposed by Helander and Tham (2003) in light

of increasing interest within human factors on the

topic of affect, and in particular pleasure, as opposed

to pain, which has generally been associated with the

established topic of safety. Helander and Tham

make reference to Kahneman’s work on hedonic

well-being as a founding theory, while also drawing

on several relevant trajectories within human factors,

namely: Kansei (feeling) engineering (Nagamachi,

1995), affective computing (Picard, 1995),

pleasurable product design (Jordan, 1998), and

Donald Norman’s insights on pleasure in design

(Norman, 2002), which has recently culminated into

a new area called positive computing (Calvo and

Peters, 2014). However, perhaps because of the

nature of the paper as an editorial, the authors do not

suggest a particular theory or provide a theoretical

framework for the concept of hedonomics; rather,

they offer it as a new area of research and practice.

Figure 1: Conceptual overview of well-being.

Hancock (who coined the term “hedonomics”

and is cited by Helander and Tham as the inspiration

for bringing attention to this topic), Pepe and

Murphy (2005) offer a deeper take on the theory and

conceptual foundations of hedonomics. Here, the

focus of hedonomics is explicitly positioned

opposite to ergonomics: where ergonomics focuses

on the prevention or alleviation of pain, hedonomics

focuses on providing or increasing pleasure. Hence,

“additive” (rather than subtractive) human factors.

Further, hedonomics is contrasted with human-

centred design, which the authors argue takes a

general stance to design (e.g. designing for the

capacities of people in general, or centaurs in

general, to use their example), rather than focusing

on an individual and their personal needs. Thus,

human-centred design must be extended to include

“individuation,” or individual-centred design.

2.3.1 Theoretical Model

The structure of the hedonomics model is based on

Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy of needs, where lower-

level needs must be met before high-level needs can

be achieved. In the hedonomics model, the first three

needs are the domain of traditional human factors:

safety, functionality, and usability. The final two

needs are the domain of hedonomics: pleasurable

experience (hedonia) and individuation (defined by

the authors as “personal perfection”). An exception

is made for usability, which the authors consider a

cross-domain factor. In the hierarchy, the needs

closest to the bottom are more relevant to a general

(or “collective”) approach to design, while the needs

closest to the top are more relevant to an

individuation approach to design.

To the authors, pleasurable experience may be

generated by designers’ use of “hedonomic

affordances,” which attempt to elicit specific

affective states in the end-user. This idea reflects

psychological conceptualizations of SWB, which is

the domain of hedonia, thus complementing the

psychological work on well-being. Individuation

may be attained by developing smart tools that allow

end-users to customize their experience, perhaps by

responding to their affective needs.

2.3.2 Critique

A review of the model combined with a close

examination of how hedonomics is described by the

authors in-text and with respect to the psychological

literature reveals some discrepancies. As expected

given the term’s inspiration (hedonia), the authors

define hedonomics as the promotion of pleasure.

However, they also at times characterize its scope as

eudaimonic. For instance: “To fulfil the needs of the

user, we need to incorporate an explicit recognition

of motivation, quality of life, enjoyment, and

pleasure into design recommendations” (Hancock et

al., 2005, p.11). Further, they argue that the concept

of individuation, which in the model is separate from

the need for a pleasurable experience, fulfils the

need for autonomy, a eudaimonic construct. Finally,

they refer to Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) work

on the nature of virtue (philosophically the domain

of eudaimonia). This reference provides motivation

for the adoption of well-being into the domain of

human factors but also serves to highlight a gap in

the model: explicit inclusion of eudaimonic factors.

These issues raise two harmonizing possibilities

for expansion of the model: (1) clarification of the

definition and scope of hedonomics, and (2)

introduction of a eudaimonic aspect to the model. To

this end, we propose an expanded human factors

model of well-being that explicitly addresses the

concept of a eudaimonics of human factors.

3 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The philosophical and psychological underpinnings

of well-being advocate at least two perspectives: a

hedonia of human factors—the already established

hedonomics—which is concerned with positive and

negative affect (and especially pleasure), but also a

eudaimonia of human factors—we propose

“eudaimonics”—which addresses flourishing as

personal expressiveness and self-realization. In

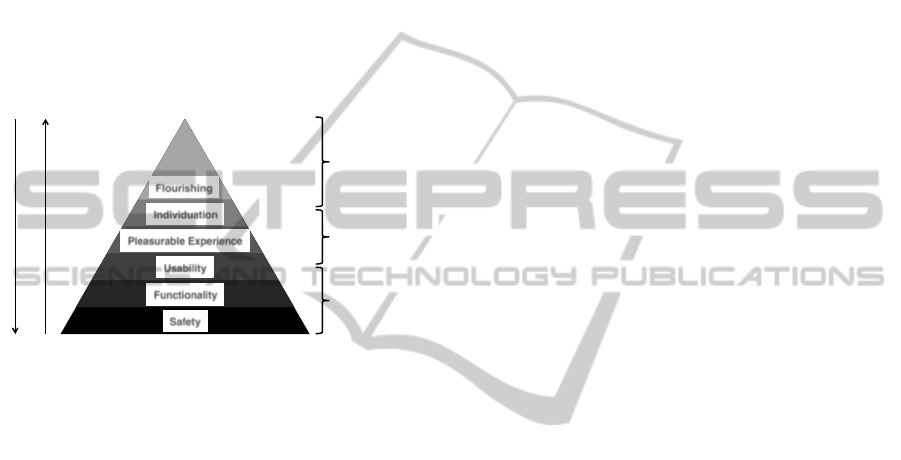

Figure 2, we offer an expanded version of Hancock

and colleagues’ hierarchy of hedonomic needs as a

general model of well-being in human factors that

includes a eudaimonic perspective.

Figure 2: A human factors model of well-being that

includes a eudaimonic aspect. Based on the hierarchy of

hedonomic needs by Hancock, Pepe and Murphy (2005),

which was based on Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy of needs.

Here, eudaimonics shares the need for

individuation with hedonomics (as per the idea that

individuation elicits autonomy, a eudaimonic

construct). The new need that represents the

eudaimonic aspect of well-being—flourishing—is a

catch-all term derived from the psychological

literature on eudaimonic well-being. Its position at

the top of the hierarchy is based on the philosophical

and psychological justifications of how hedonia and

eudaimonia are positioned with respect to each other

as well as the original model’s use of a scale of

global-individual appropriateness.

3.1 Application to Ageing Well

If we assume that optimal well-being is a common

goal of all adults regardless of age, then systems,

technologies, and devices must be designed with all

elements of the model in mind. When these systems

are designed to replace or augment changing human

functions, such as mobility, sensory and cognitive

functions, it is insufficient to only consider human

factors and hedonomic elements. Further, the

context in which these systems are used may have a

direct impact on an individual’s sense of self and

ability to flourish, particularly as the individual faces

new challenges due to changes in their health and

well-being status as they age. Finally, efforts are

required to determine how the design of assistive

technologies and systems can positively affect a

person’s transitioning state of well-being and sense

of self resulting from the aging process.

Going forward, measures of well-being that

include hedonic and eudaimonic factors must be

adapted or devised so that they are actionable by and

fathomable to designers and users, similar to how

usability measures (Rogers et al., 2011) have been

developed. For instance, Huta and Ryan’s (2010)

Hedonic and Eudaimonic Motives for Activities

(HEMA) instrument may be used to assess human-

system interactions for specific contexts, tasks and

activities, but this needs to be tested in human

factors work. Further, eudaimonic well-being design

guidelines similar to the safety, functionality and

usability triad that can be found in textbooks and

standards, e.g. the ISO/TC 159 Ergonomics

standard, are required. This will involve empirical

human factors studies in which eudaimonia, as well

as hedonia and other aspects of well-being (e.g. life

satisfaction), are assessed.

4 CONCLUSIONS

An initiative towards establishing well-being as an

important factor in the fit between humans and

systems is underway. To this end, we have identified

eudaimonics as a potential domain that complements

the established area of hedonomics. We have

developed a conceptual framework that distinguishes

the two and is informed by relevant philosophical

and psychosocial concepts. We have discussed how

this framework may be used to understand the

ageing process and the affect on ageing people. We

can suggest several trajectories for future work:

Adapting existing, validated psychological

instruments for use in human factors research.

Development of design guidelines for

eudaimonic systems.

Validation and expansion of the model: While

founded on sound theoretical work that has

empirical backing in psychology, the model

needs to be validated with respect to human

factors knowledge.

Eudaimonic

s

Hedonomics

HF/E

Safety

Functionality

Usability

Pleasurable Experience

Individuation

Individual

Collective

Flourishing

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We have been funded in part by the Natural Sciences

and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

REFERENCES

Bradburn, N. M., 1969. The structure of psychological

well-being, Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Calvo, R. A. & Peters, D., 2014. Positive computing:

Technology for wellbeing and human potential,

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., 1991. Flow: The psychology of

optimal experience, New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

Deci, E. L., 1971. Effects of externally mediated rewards

on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 18(1), p.105.

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M., 2008. Hedonia, eudaimonia,

and well-being: an introduction. Journal of Happiness

Studies, 9(1), pp.1–11.

Diener, E., 1984. Subjective well-being. Psychological

Bulletin, 95, pp.542–575.

Diener, E. et al., 1999. Subjective well-being: Three

decades of progress. Psychological bulletin, 125(2),

p.276.

Graham, C., 2012. The pursuit of happiness: An economy

of well-being, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution

Press.

Hancock, P. A., Pepe, A. A. & Murphy, L. L., 2005.

Hedonomics: The power of positive and pleasurable

ergonomics. Ergonomics in Design, 13(1), pp.8–14.

Helander, M. G. & Tham, M. P., 2003. Hedonomics—

affective human factors design. Ergonomics,

46(13/14), pp.1269–1282.

Huta, V., 2013. Pursuing eudaimonia versus hedonia:

Distinctions, similarities, and relationships. In The best

within us: Positive psychology perspectives on

eudaimonia. Washington, DC: American

Psychological Association, pp. 139–158.

Huta, V. & Ryan, R. M., 2010. Pursuing pleasure or

virtue: The differential and overlapping well-being

benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. Journal

of Happiness Studies, 11(6), pp.735–762.

Jordan, P. W., 1998. Human factors for pleasure in

product use. Applied Ergonomics, 29(1), pp.25–33.

Kahneman, D., Diener, E. & Schwarz, N. eds., 1999. Well-

being: Foundations of hedonic psychology, New York,

NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Keyes, C. L. M., Shmotkin, D. & Ryff, C. D., 2002.

Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of

two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 82(6), pp.1007–1022.

Linley, P. A. et al., 2009. Measuring happiness: The

higher order factor structure of subjective and

psychological well-being measures. Personality and

Individual Differences, 47(8), pp.878–884.

Maslow, A. H., 1970. Motivation and personality 3rd ed.,

New York, NY: Longman.

Maslow, A. H., 1962. Toward a psychology of being,

Princton, NJ: Van Nostrand Press.

Meister, D., 1999. The history of human factors and

ergonomics

, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Nagamachi, M., 1995. Kansei engineering: A new

ergonomic consumer-oriented technology for product

development. International Journal of industrial

ergonomics, 15(1), pp.3–11.

Nordbakke, S. & Schwanen, T., 2014. Well-being and

mobility: A theoretical framework and literature

review focusing on older people. Mobilities, 9(1),

pp.104–129.

Norman, D., 2002. Emotion & design: Attractive things

work better. interactions, 9(4), pp.36–42.

Peterson, C. & Seligman, M. E., 2004. Character

strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification,

Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Picard, R. W., 1995. Affective Computing, Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press.

Proctor, C., Tweed, R. & Morris, D., 2014. The naturally

emerging structure of well-being among young adults:

“Big Two” or other framework? Journal of Happiness

Studies, pp.1–19.

Rogers, Y., Sharp, H. & Preece, J., 2011. Interaction

design: Beyond human-computer interaction 3rd ed.,

Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L., 2001. On happiness and

human potentials: A review of research on hedonic

and eudaimonic well-being. Annual review of

psychology, 52(1), pp.141–166.

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L., 2000. Self-determination

theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation,

social development, and well-being. American

Psychologist, 55(1), pp.68–78.

Ryff, C. D., 1989. Happiness is everything, or is it?

Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-

being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

57(6), pp.1069–1081.

Ryff, C. D. & Keyes, C. L. M., 1995. The structure of

psychological well-being revisited. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), p.719.

Ryff, C. D. & Singer, B. H., 2008. Know thyself and

become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to

psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness

Studies, 9(1), pp.13–39.

Sirgy, M. J., 2012. The psychology of quality of life:

Hedonic well-being, life satisfaction, and eudaimonia

2nd ed., New York, NY: Springer.

Vicente, K. J., 2004. The human factor: Revolutionizing

the way people live with technology, New York, NY:

Routledge.

Waterman, A.S., 1990. Personal expressiveness:

Philosophical and psychological foundations. Journal

of Mind and Behavior, 11(1), pp.47–74.

Waterman, A.S., 2008. Reconsidering happiness: A

eudaimonist’s perspective. The Journal of Positive

Psychology, 3(4), pp.234–252.

Waterman, A.S. et al., 2010. The Questionnaire for

Eudaimonic Well-Being: Psychometric properties,

demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity.

The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), pp.41–61.

Waterman, A.S., 1993. Two conceptions of happiness:

Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and

hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 64(4), pp.678–691.

World Health Organization, 1997. Measuring quality of

life: The World Health Organization quality of life

instruments.