Towards Enhancing Communication Between Caregiver Teams and

Elderly Patients in Emergency Situations

Syed Atif Mehdi

1

, Artem Avtandilov

1,2

, Shah Rukh Humayoun

2

and Karsten Berns

1

1

Robotics Research Lab, University of Kaiserslautern, Kaiserslautern, Germany

2

Computer Graphics and HCI Group, University of Kaiserslautern, Kaiserslautern, Germany

Keywords:

Healthcare Robotics, Interacting Robots at Home, Graphical User Interfaces, Web-based Interaction, Mobile

Platform, Evaluation Study.

Abstract:

The paper presents a framework developed for facilitating care giver staff to interact with an elderly person

in an emergency situation alone at home. The framework uses an autonomous mobile robot (ARTOS) as a

communication medium in the home environment to establish a communication channel. The novel idea in

this work is to facilitate emergency responding teams by also providing them access and control over the robot

through mobile devices. The user evaluation study of the developed framework demonstrates the effective

usability of the system even by users having no prior experience or training.

1 INTRODUCTION

The elderly population in developed countries is

steadily increasing (Lehr, 2007). In many situations

these people live alone in their homes and this re-

quires urgent assistance in case of some emergency

situation happens to the person. Currently, many re-

search groups are devoting their efforts in develop-

ing robots that can perform several tasks in a typical

home environment. They focus normally on perform-

ing some activity in the home environment like fetch-

ing objects (Graf et al., 2009), folding laundry (Cio-

carlie et al., 2010), etc. In some cases, a robotic plat-

form has also been used as a communication medium

between the elderly person and a family member or

a caregiver staff (Merten et al., 2012; Rumeau et al.,

2012). These robots can be more beneficial if they

can provide support to the health care staff when an

emergency happens to an elderly person. One such

support would be to initiate the call to the health care

staff informing about the situation, other possibilities

would be to allow the robot to be remotely controlled

without the need of any sophisticated hardware (Dee-

gan et al., 2008; Mehdi et al., 2014).

The main contribution of our current work is de-

velopment of a framework for establishing communi-

cation between the elderly person and the emergency

responding teams via a mobile robotic platform and

performing evaluation studies describing the effec-

tiveness of the developed approach. It is an exten-

sion to previously developed interfaces (Mehdi et al.,

2014) where only staff at health care center was able

to communicate with the elderly person using the mo-

bile robot as a platform.

In order to illustrate the concept and developed

framework, this paper has been organized as fol-

lows. Section 2 presents an overview of communi-

cation mediums used during an emergency scenario.

The framework developed for establishing commu-

nication between the caregivers and the emergency

teams is described in Section 3. This section also

describes the communicating partners in detail. Sec-

tion 4 describes the communication between the part-

ners. Section 5 provides details of the conducted eval-

uation studies as well as discusses the results. Finally,

Section 6 provides the conclusion and gives directions

to the future work.

2 RELATED WORK

Crucial parts of the emergency response environments

are interaction between different entities in the envi-

ronment and the channels available for this interac-

tion. Many emergency services around the world have

upgraded their hardware and software to meet the de-

mand; however, vast majority of them still rely on the

voice communication solutions as a primary source

of information when most up-to-date information is

118

Atif Mehdi S., Avtandilov A., Rukh Humayoun S. and Berns K..

Towards Enhancing Communication Between Caregiver Teams and Elderly Patients in Emergency Situations.

DOI: 10.5220/0005492401180126

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AgeingWell-

2015), pages 118-126

ISBN: 978-989-758-102-1

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

required. Many previous works (Reddy et al., 2009;

Paul et al., 2008; Kyng et al., 2006) have been tack-

ling the issues in systematic approach to these frame-

works.

Reddy et al. raised questions about the crisis man-

agement and how technologies could affect the emer-

gency services (Reddy et al., 2009). They concluded

that the teams of first responders and the service cen-

ter have strong socio-technical aspect in interaction

as well as pointing out that team-to-team and team-

to-emergency sight communication are difficult to or-

ganize. On the other hand, Paul et al. found the role

of technologies in the process as uncertain due to the

opinion provided by the physicians participated in the

study (Paul et al., 2008). While Kyng et al. took

a closer approach into how interactive such services

could be, by setting specific challenges to the existing

systems handling emergencies (Kyng et al., 2006). By

illustrating the important role of the live video feed

when handling an emergency, they provided sufficient

proof that such solutions may be beneficial.

All the above-mentioned work took widely the

theoretic approach to the problem; however, most of

the work providing the real communication and engi-

neering solutions are developed in the industry trying

to meet market needs. Most pervasive approach in

the industry developed by Motorola

1

provides a solu-

tion for the emergencies occurring in largely accessi-

ble public spaces, relies on the government’s access

to the CCTV recordings in real time, dedicated emer-

gency channels and possibly a large impact. It aims

at improving response times, enhancing safety for re-

sponders, and enabling better communication with

emergency service center. This approach is based

on a steady ground of communication technologies

finely tuned for the needs of first responders; how-

ever, it lacks the individuality while tackling bigger

problems. As much as it is effective in the afore-

mentioned type of emergencies, it lacks individual ap-

proach when only one patient is endangered and does

not provide interactive communication with the emer-

gency scene.

Other solutions in the market like Mobile So-

lutions

2

and PK

3

take another approach trying to

strengthen communication between different emer-

gency services such as firefighters, medical personnel

and law enforcement by providing extended database

support with immediate access to records tackling

mostly management problems. Mobility for the com-

mand center is showcased by PK. It could be installed

on-site and serves as an authentication center and is-

1

http://www.motorolasolutions.com

2

http://www.elliottmobilesolutions.com

3

http://www.pk.nl

sues tasks to all service members using hand-held de-

vices.

As these industry approaches target communica-

tion between the first responders and their command

centers, they lack of the channels that are difficult to

organize (Kyng et al., 2006), namely live video feed

from the place where emergency occurred when it is

in the comfort of patients home. These communi-

cation strategies consider facilitating interaction be-

tween the diseased person and the service center. Al-

though this is important but these do not provide any

framework for establishing communication between

the emergency responding team and the person in dis-

tress, which could be helpful in better informing both

the team and the person.

3 METHODOLOGY

The main emphasis in this paper is to develop a

framework for establishing communication channel

between the Emergency Responding Team (ERT) and

the elderly person in an emergency situation at the

home environment. Since it is not known in advance

which ERT will be able to reach the person at earli-

est; therefore, the emergency situation is reported to

the Health Service Center (HSC). The HSC is then

responsible to send the request to the ERTs and con-

tact information is provided to only that ERT which

accepts to undertake the responsibility. The respon-

sible ERT can then communicate with the person us-

ing the autonomous mobile robot as a platform and

navigate it in the home environment to understand the

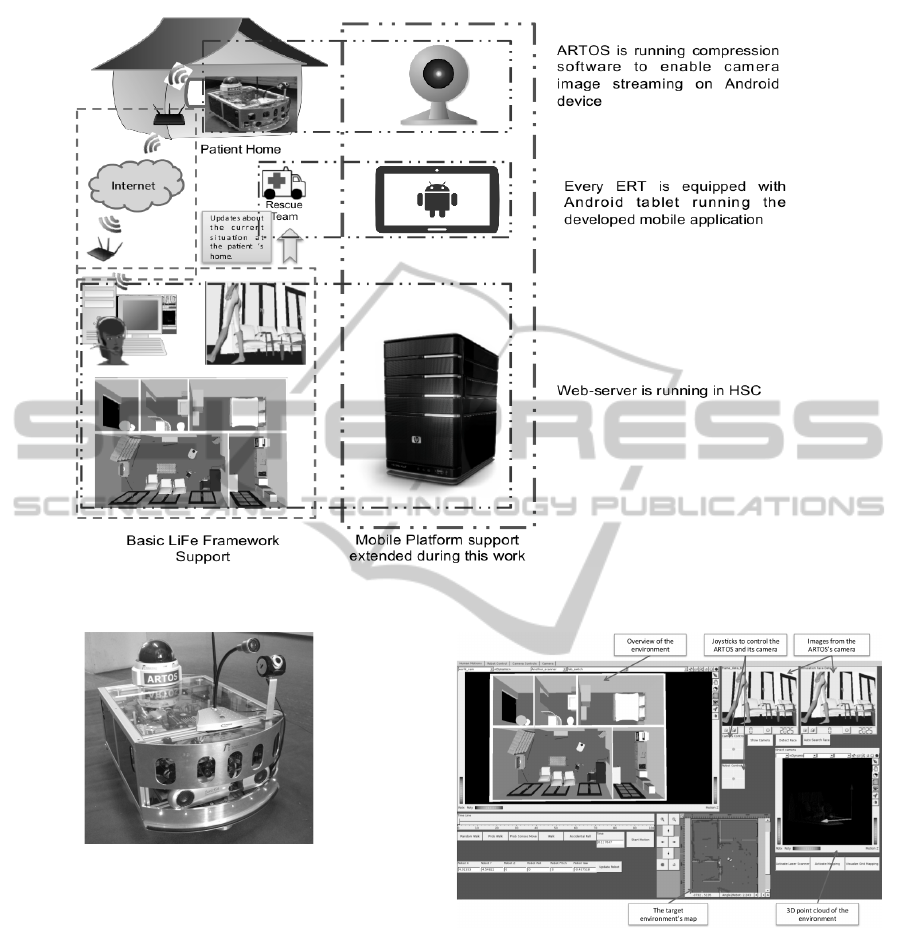

situation. Figure 1 gives an overview of the complete

framework.

3.1 Autonomous Mobile Robot

The Autonomous Robot for Transport and Service

(ARTOS) (see Figure 2) has been developed at the

Robotics Research Lab, University of Kaiserslautern

in order to investigate challenges in providing to el-

derly people living alone in their homes. The robot

is capable of driving autonomously in the home en-

vironment and detects obstacles using its laser scan-

ner, ultrasonic sensors, and bumper sensor. It is

also capable of learning the daily routine of the per-

son and searching the person using the learned rou-

tine (Mehdi, 2014). The robot can also be tele-

operated by caregiver staff at health service center us-

ing a joystick in the Graphical User Interface (GUI) to

observe the home environment (Mehdi et al., 2014).

TowardsEnhancingCommunicationBetweenCaregiverTeamsandElderlyPatientsinEmergencySituations

119

Figure 1: Overview of the developed framework.

Figure 2: Autonomous Robot for Transport and Service

(ARTOS).

3.2 Health Service Center

The Health Service Center (HSC) is the first point of

contact that receives the emergency help request from

ARTOS. After receiving the request, they can tele-

operate the robot to evaluate the situation in hand and

verify any false alarm. The GUI (see Figure 3) at the

center provides them with the view of the home using

camera on the robot. After verification they can trans-

fer the help request to the mobile teams to respond the

emergency situation.

Figure 3: The GUI at HSC that visualizes the elderly per-

son’s home environment and provides interactions to con-

trol ARTOS and the camera.

3.3 Emergency Response Teams

Emergency Response Teams (ERTs) respond to the

elderly person in an emergency situation. After re-

ceiving the information from HSC, they can use AR-

TOS as a communication medium to evaluate the sit-

uation at home and to talk with the person in distress.

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

120

4 COMMUNICATION BETWEEN

ENTITIES

The emergency situation is notified by the ARTOS

to the staff at HSC on their Graphical User Inter-

faces (GUI). The notification contains the information

about the person and the possible emergency situa-

tion. The staff member at HSC can view the map of

the home environment and the obstacles in the envi-

ronment as detected by the sensors installed on the

robot using the GUI. The staff member can also re-

motely control the robot using the GUI to access the

situation and rectify in case a false alarm has been

generated.

In case a valid emergency situation is recognized,

the staff member at HSC can dispatch a message to

notify all the ERTs or the nearest ERT about the sit-

uation. This is performed using the developed web

server running at the HSC. The web server commu-

nicates with the Google Cloud Messaging (GCM)

Services for dispatching the notification. The staff

member can also monitor the location of each ERT

by tracking their GPS coordinates in the integrated

Google Maps. The web server at the HSC han-

dles communication, feedback, status updates and

database queries with the mobile application installed

on the ERT mobile devices. It has been developed as a

multi-user web-interface that can automatically prior-

itizes lists of ERTs and pending emergencies, which

allows HSC staff to act effectively and can decrease

time needed to respond to an emergency request.

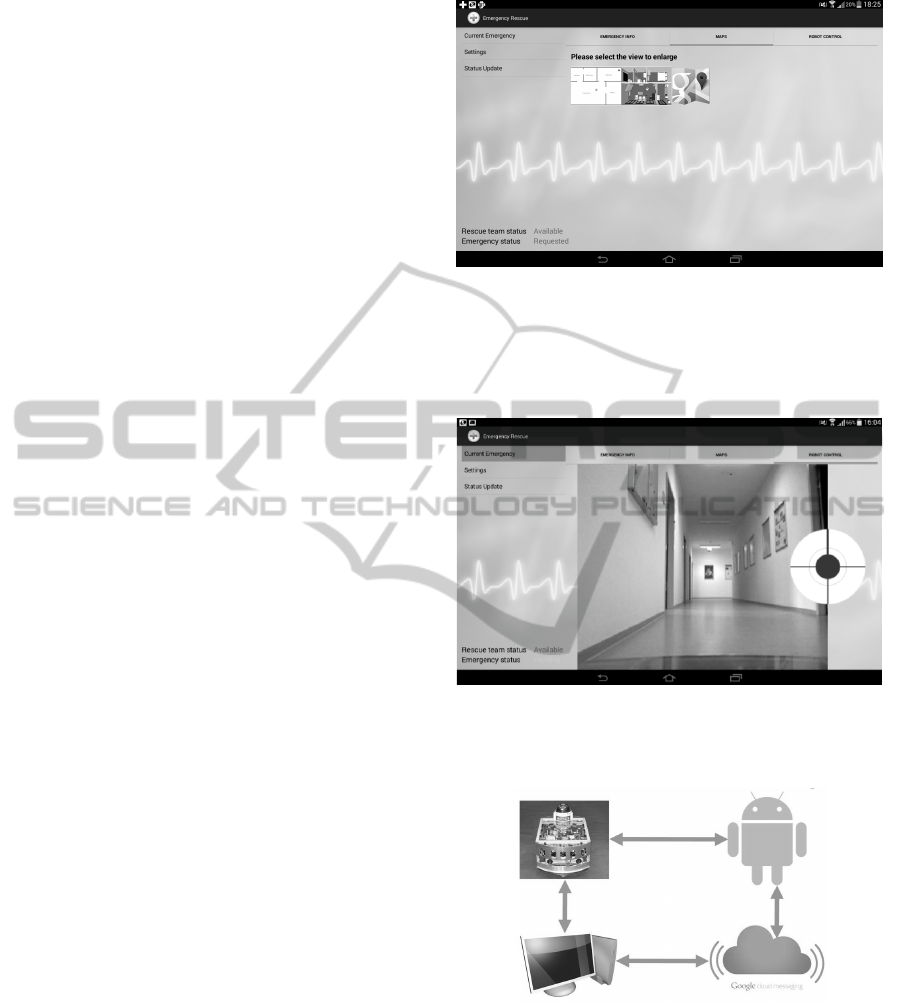

An Android application has been specifically de-

veloped for the ERTs, to communicate with both HSC

and ARTOS to receive most up-to-date information

about the patient, their location, and the situation

that they are about to get involved. The function-

ality of the application includes receiving live video

image from ARTOS, joystick control of the robot to

explore the environment, status reports to the HSC,

database access for extended information about the

patient, and navigation options. Figure 4 and Figure 5

show screenshots of the developed mobile app for the

ERTs with the options of map selection and ARTOS

control. The mobile app receives and interprets the

messages received from the GCM. The message re-

ceived contains information about the patient, address

and Skype id of ARTOS. The GUI of the application

facilitates the ERT in determining the acceptance or

rejection of the job. In case of acceptance, it further

receives the information about the Skype id and IP

address of the ARTOS. Once the vital information is

received, ERT can directly communicate with the per-

son in distress and does not require HSC, which sig-

nificantly decreases the stressful job at HSC. Figure 6

Figure 4: A screenshot of the developed mobile app for the

ERTs that shows the availability of three maps, i.e., map

for ARTOS location in the home environment, the home

environment 3D map, and the Google map to the elderly

person home. Clicking on any of them shows in full screen

the selected map.

Figure 5: A screenshot of the developed mobile app for the

ERTs that shows the camera view of the ARTOS, while the

joy stick on the right side of the screen is used to control the

ARTOS movement.

Figure 6: Communication between the server at HSC and

ERT using Google Cloud Messaging. Once information is

received by the ERT, they can directly communicate with

ARTOS using the developed Android App.

depicts the communication between ARTOS, HSC

and ERTs.

TowardsEnhancingCommunicationBetweenCaregiverTeamsandElderlyPatientsinEmergencySituations

121

5 THE EVALUATION STUDIES

The main contribution of our framework is estab-

lishing a communication platform between the health

care staff at various levels (e.g., between the staff at

HSC and the mobile response teams) and the elderly

person at home. However, in our conducted evalu-

ation studies we mainly focused on the mobile plat-

form that we developed to be used by the mobile

ERTs.

We conducted the evaluation studies at two stages.

The first evaluation study was carried out with

three usability experts using the heuristic evalua-

tion (Nielsen and Molich, 1990; Nielsen, 1994) ap-

proach. This evaluation ran on the first implemented

prototype of the developed mobile app and the goal

was to find out the possible usability flaws in the

mobile app using the ten heuristics proposed by

Nielsen (Nielsen, 1994). Based on the results of

this evaluation study by experts, we redesigned our

mobile app user interface and made the suggested

changes.

The second evaluation study was conducted with

10 participants having different background using

the controlled task-based evaluation experiment ap-

proach. They were also given closed-ended and open-

ended questionnaires at the end of experiment in or-

der to know their feedback. These participants were

mostly researchers and students from the University

of Kaiserslautern, as the goal of the second evalua-

tion study was to analyze whether the developed mo-

bile app (which will be eventually used by ERTs) is

easy to use without any prior training or expertise.

In the following subsections, we provide details

of the conducted heuristic evaluation study followed

by the user evaluation study in the controlled environ-

ment.

5.1 The Heuristic Evaluation Study

The heuristic evaluation study was done with three us-

ability researchers from the Computer Graphics and

HCI group of the University of Kaiserslautern. They

evaluated the first implemented prototype of the mo-

bile app using the ten heuristics and ranked the user

interface giving a number from 0 to 4, where 0 means

no problem at all while 4 means usability catastro-

phe (Nielsen, 1994). The goal was to find out usabil-

ity issues in the early stage of the mobile app devel-

opment in order to improve the design and UI based

on this evaluation.

A list of tasks were given to these experts con-

sisted of the main features of the developed mobile

app: i.e., managing settings, performing status up-

dates, giving response to the emergency requests, es-

tablishing Skype call with the patient, sending feed-

back to the server, observing elderly person’s house-

hold map, route planning with Google Maps, and con-

trolling the ARTOS with joystick control option.

An introduction of the mobile app was given to

these experts before they started to evaluate it. Fur-

ther, the task description from the users’ point of view

was also given to them. They were also allowed to ask

details about any UI element or task during the evalu-

ation. In order to maintain the settings, the same per-

son was given the chance to explain the mobile app

and tasks during the evaluation. A form was given

to these experts in order to record their feedback re-

garding the ten heuristics and their overall comments

regarding any particular task or UI element.

Figure 7 shows the feedback of these three experts

using the ten heuristics, where the score indicates the

average of their given ranking in all tasks. The feed-

back indicated that some changes needed to be done

for preventing errors and extending the visibility of

the system status. However, there was not any major

usability problem or usability catastrophe. The worst

average grade of 2.0 from one expert was received

in the category of help and documentation criteria.

As our mobile app is intended to be used for pro-

fessional purposes by ERTs, help and documentation

must be sufficient for users with any level of compe-

tency and should provide in-depth review of the fea-

tures. Other major issues were in the cases of fifth and

ninth heuristics (average score of 1.25 and 1.08 by all

experts, see Figure 7), which indicated insignificant

lack of clarity on how to prevent and recover from er-

rors.

These experts also gave their suggestions for im-

proving the usability of the developed mobile app,

e.g., to introduce status fields of the rescue team and

the current emergency. These suggestions were then

analyzed and taken into account while developing the

final version of the app.

5.2 The User Evaluation Study

The goal of this conducted user evaluation study was

to analyze whether the developed mobile app is easy

to use without any prior training or expertise. There-

fore, we were interested in finding out the effective-

ness, efficiency, and user satisfaction aspects of our

developed app, as it will be used by ERTs for com-

municating with the HSC and the elderly person in

the emergency situation. The following metrics were

derived from the GQM model (Basili et al., 1994).

• Metrics for effectiveness: We measure and com-

pare the percentage of corrected completed tasks.

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

122

!" !#$" %" %#$" &" &#$"

%'"()*)+),)-."/0"*.*-12"*-3-4*"

&'"53-67"+1-8119"*.*-12"39:";13,"8/;,:"

<'"=*1;"6/9-;/,"39:"0;11:/2"

>'"?/9*)*-196."39:"*-39:3;:*"

$'"@;;/;"A;1B19C/9"

D'"E16/F9)C/9";3-71;"-739";163,,"

G'"H,1I)+),)-."39:"1J6)196."/0"4*1"

K'"L1*-71C6"39:"2)9)23,)*C6":1*)F9"

M'"N1,A"4*1;*";16/B1;"0;/2"1;;/;*"

%!'"N1,A"39:":/64219-3C/9"

@IA1;-"%" @IA1;-"&" @IA1;-"<"

Figure 7: Average score of the mobile app UI using the ten heuristics.

• Metrics for efficiency: We measure and compare

the time needed for completing each task.

• Metrics for user satisfaction: We collect partici-

pants’ feedbacks and compare them.

We combined these metrics as suggested by the

Technology Acceptance Model (Venkatesh et al.,

2003). For collecting the participants’ feedbacks on

how to improve the developed mobile app, we chose

an open-ended questionnaire form in order to collect

their comments. We formulated the set of hypotheses

as:

• H1: We expect an effectiveness of more than

90%, which means that in total participants accu-

racy of the completed task would be at least 90%.

• H2: On average, both groups (i.e., the little or

inexperienced group and the experienced group)

achieve nearly the equal efficiency in completing

the given tasks.

• H3: Participants agree that the developed mobile

app is acceptable and useful for collaborating with

HSC and ARTOS robot for handling the emer-

gency request and for performing the rescue op-

eration.

5.2.1 Study Design and Experiment Settings

Based on the identified goals and hypotheses, we de-

signed this study as a controlled experiment under

laboratory conditions with a maximum time frame of

45 minutes per participant. This allowed us enough

time to have basic introduction explaining what is the

idea behind the developed mobile app and what kind

of environment participants will be interacting with.

We ran the study with 10 participants (6 males, 4

females), who were researchers and students from the

University of Kaiserslautern having different back-

grounds. Only one of them had prior experience in

dealing with emergency situations. However, four of

the participants had very little or no experience at all

in using smartphones or smart tablets, while remain-

ing six participants were experienced users of smart-

phones. Further, four of the participants never had any

experience of robotics while five of them had some

basic experience of robotics. The remaining one par-

ticipant was an expert in robotics. The age range of

participants in this study was from 20 to 44 years with

a median of 27.8 years old.

The participants were given four tasks to com-

plete one by one. Completion of the tasks was timed

and participants had a chance to ask questions dur-

ing the experiment in case they run into some tech-

nical difficulties or unable to complete the task by

themselves. An evaluator was there to carefully write

down the comments participants had upon comple-

tion of each task in order to make sure that immedi-

ate feedback is possible. After tasks were completed,

participants were presented with two questionnaires

forms: closed-ended questionnaires form and open-

ended questionnaires form. The closed-ended ques-

tionnaires form was based on nine questions, where

each question offered a selection from six options on

a Likert scale (Likert, 1932) (scale of 1 to 5 to show

how much participants agree with the given statement

and an additional option “Don’t know”). The open-

TowardsEnhancingCommunicationBetweenCaregiverTeamsandElderlyPatientsinEmergencySituations

123

ended questionnaires form was aimed at general feed-

back in which the participants were asked to list any

pros and cons they have identified in the developed

mobile app and an opportunity to voice any other

comments or suggestions.

The test was performed in the environment of the

laboratory, with the participants seated in an office

chair with no table and the tablet was freely in their

hands. Participants were interacting with the mobile

app using the standard touch features with no prior ac-

cess to the platform in order to ensure no prior training

or familiarity with the features.

5.2.2 Tasks Description

The test consisted of the following four tasks:

• Task 1: After an emergency request is issued:

find the basic information about the patient, plan

the route to the patient home on the Google map,

and accept the emergency request.

• Task 2: After an emergency request is issued: ini-

tiate a Skype call and then decline the emergency

request.

• Task 3: After accepting an emergency request:

open additional options for the emergency situa-

tion, explore the map of the elderly patient house-

hold, control the robot using the joystick, and nav-

igate it to the patient.

• Task 4: As a team leader of the new started shift:

enter your team details in the app settings and up-

date the availability status.

5.2.3 Results and Discussions

In this subsection, we briefly discuss the results of the

study. Overall, results of this conducted user evalua-

tion study indicate satisfactory results in both groups.

From the effectiveness perspective, all of the par-

ticipants were able to complete the tasks successfully

and accurately, which shows a high rate of effective-

ness and proves that the developed mobile app is easy

to operate. This also proves our hypothesis H1 in

which we were expecting that on average participants

would be able to accurately complete the tasks at least

90% of the total tasks.

The results from the efficiency perspective (i.e.,

the time completion) are listed in Figure 8, which

shows the average time completion per task for the

both groups (i.e., little or inexperienced users and ex-

perienced users). Participants from both groups do

not show any significant differences in time complet-

ing any of the tasks. This demonstrates that the de-

veloped mobile app is easy to use and does not re-

quire much experience in order to complete the task.

The main task (i.e., Task 3) that took most of the time

was navigating the robot using the joystick and this

is natural due to the speed of ARTOS. This brings

us to the importance of the closed-ended question-

naires (see Table 1) and open-ended feedback from

the participants. Even though most of the participants

agreed that “It was easy to handle the robot with the

joystick”, the average grade of 3.8 is the lowest com-

paring to other features used in the developed mo-

bile app. This was due to the security features of the

robot navigation system and participants’ unfamiliar-

ity with the environment. In the real life scenarios,

trouble of making yourself familiar with a new envi-

ronment could facilitate emergency response team’s

actions when they arrive to the endangered person’s

house and when time matters the most. Overall, the

results shown in Figure 8 prove our hypothesis H2, in

which we were expecting nearly the equal efficiency

from the participants with little or no experience com-

pared to the experienced participants.

0" 20" 40" 60" 80" 100" 120" 140" 160"

Task"1"

Task"2"

Task"3"

Task"4"

Li/le"or"no"experience" Experienced"

Figure 8: Average time completion in seconds of partici-

pants in both groups.

When we look at the participants’ feedback in

the closed-ended questionnaires (see Table 1), we ob-

serve an average score of more than 4 in most of the

cases, which shows high acceptance ratio of our mo-

bile app amongst the participants. However, in ques-

tion 3 (regarding the handling of robot through joy-

stick) and question 4 (recovering from mistakes) we

see a lower score. As described above, the first rea-

son was in difficulty of handling the ARTOS while in

the second case few of the participants were unfamil-

iar with the Android platform that allows users to go

back to the previous stage through the Back naviga-

tion button. Overall, the results of participants in the

closed-ended questionnaires also prove our hypothe-

sis H3, in which we were expecting a high acceptance

ratio from the participants.

Further, the feedback provided by the open-ended

questionnaires reveals the particular features of the

mobile app participants were or were not satisfied

with. The open-ended questionnaires were built

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

124

!! "! #! $! %! &'(! )*+,-./

!1:!It!was!easy!to!see!the!current!status!of!the!system!

0! 1! 1! 5! 3! 0! 4/

!2:!It!was!easy!to!change!Team!availability!status!

0! 1! 2! 0! 7! 0! 4.3/

!3:!It!was!easy!to!handle!the!robot!with!the!joysBck!

0! 2! 2! 4! 2! 0! 3.8/

!4:!It!was!easy!to!recover!from!mistakes!

0! 0! 3! 3! 2! 2! 3.9/

!5:!I!found!it!easy!to!locate!the!needed!features!in!the!layout!of!the!app!

1! 0! 1! 4! 4! 0! 4/

!6:!It!was!easy!to!complete!provided!tasks!

0! 1! 0! 3! 6! 0! 4.4/

!7:!It!was!clear!from!the!icons!the!intended!features!they!represent!

0! 0! 1! 2! 7! 0! 4.6/

!8:!I!found!the!interface!easy!to!use!

0! 0! 1! 6! 3! 0! 4.2/

!9:!I!would!recommend!to!use!this!system!for!emergency!scenarios!regularly!

0! 0! 0! 4! 4! 2! 4.5/

Table 1: Participants’ feedback in closed-ended questionnaires form. Here, 1 means “strongly disagree” and 5 means “strongly

agree”. The last column shows average score of all participants.

around the idea that the participant will give some

basic feedback upon completion of every task and

the evaluator will write it down, and after the par-

ticipant completes all of the tasks he/she will be al-

lowed to list pros and cons of the mobile app as well

as giving any other general feedback. The collected

open-ended feedback showed participants’ appreci-

ation towards the clarity in the GUI’s visualization,

namely the icons that were always reflecting the fea-

ture underneath it. They were also sharing their pos-

itive experience on how the interface was clear and

reflecting the purpose of the mobile app. Among

the cons participants were listing lack of the source

for help when something was unclear and noting that

they were ready to operate the robot if it was mov-

ing around faster; therefore, saying that it was a little

slower than they expected. One of the other common

feedback responses was initial confusion with the log

in mechanism for the team. Participants expected to

be allowed to put their personal details in the mo-

bile app, while they actually only needed to pick their

identification (the badge number) to log in, which was

specifically implemented to reduce time it takes to log

in and avoid possible typos when entering the details.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper has demonstrated the use of a frame-

work that can facilitate communication channel be-

tween an elderly person in emergency situation at a

home environment, health service center and emer-

gency responding teams. The autonomous mobile

robot, AROTS, provides the channel for establishing

this communication. The possibility of remotely con-

trolling ARTOS to analyze the situation by moving

the robot to different rooms and observe the images

sent by the robot, enriches the user experience.

In the future, we plan to perform detailed evalua-

tion studies in real environment settings to check the

feasibility and effectiveness of the complete frame-

work. Further, we also intend to develop a communi-

cation channel between different emergency respond-

ing teams in order to provide a better collaboration

between these teams to tackle the emergency situation

more effectively.

REFERENCES

Basili, V. R., Caldiera, G., and Rombach, H. D. (1994). The

goal question metric approach. In Encyclopedia of

Software Engineering. Wiley.

Ciocarlie, M., Hsiao, K., and Jones, E. (2010). Towards

reliable grasping and manipulation in household envi-

ronments. In 12th International Symposium on Exper-

imental Robotics, ISER.

Deegan, P., Grupen, R., Hanson, A., Horrell, E., Ou,

S., Riseman, E., Sen, S., Thibodeau, B., Williams,

A., and Xie, D. (2008). Mobile manipulators for

assisted living in residential settings. Autonomous

Robots, Special Issue on Socially Assistive Robotics,

24(2):179–192.

Graf, B., Reiser, U., Hagele, M., Mauz, K., and Klein, P.

(2009). Robotic home assistant Care-O-bot 3 - prod-

uct vision and innovation platform. In IEEE Workshop

on Advanced Robotics and its Social Impacts, pages

139–144, Tokyo. IEEE.

TowardsEnhancingCommunicationBetweenCaregiverTeamsandElderlyPatientsinEmergencySituations

125

Kyng, M., Nielsen, E. T., and Kristensen, M. (2006). Chal-

lenges in designing interactive systems for emergency

response. In Proceedings of the 6th Conference on De-

signing Interactive Systems, DIS ’06, pages 301–310,

New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Lehr, U. (2007). Population Ageing. In Online Handbook

Demography. Berlin Institute for Population and De-

velopment.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of atti-

tudes. Archives of Psychology, 22(140):1–55.

Mehdi, S. A. (2014). Using the Human Daily Routine for

Optimizing Search Processes using a Service Robot in

Elderly Care Applications. PhD thesis, Robotics Re-

search Lab, Department of Computer Science, Uni-

versity of Kaiserslautern.

Mehdi, S. A., Humayoun, S. R., and Berns, K. (2014). Life-

support: An environment to get live feedback dur-

ing emergency scenarios. In Proceedings of the 8th

Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction:

Fun, Fast, Foundational, pages 935–938, Helsinki,

Finland.

Merten, M., Bley, A., Schr

¨

oter, C., and Gross, H.-M.

(2012). A mobile robot platform for socially assistive

home-care applications. In 7th German Conference

on Robotics, ROBOTIK ’12, pages 233–238, Munich,

Germany.

Nielsen, J. (1994). Enhancing the explanatory power of

usability heuristics. In Conference on Human Fac-

tors in Computing Systems, CHI 1994, Boston, Mas-

sachusetts, USA, April 24-28, 1994, Proceedings,

pages 152–158.

Nielsen, J. and Molich, R. (1990). Heuristic evaluation

of user interfaces. In Conference on Human Factors

in Computing Systems, CHI 1990, Seattle, WA, USA,

April 1-5, 1990, Proceedings, pages 249–256.

Paul, S. A., Reddy, M., Abraham, J., and DeFlitch, C.

(2008). The usefulness of information and commu-

nication technologies in crisis response. AMIA Annu

Symp Proc, 2008:561–565. amia-0561-s2008[PII].

Reddy, M. C., Paul, S. A., Abraham, J., McNeese, M., De-

Flitch, C., and Yen, J. (2009). Challenges to effective

crisis management: Using information and commu-

nication technologies to coordinate emergency medi-

cal services and emergency department teams. Inter-

national Journal of Medical Informatics, 78(4):259–

269.

Rumeau, P., Vigouroux, N., Boudet, B., Lepicard, G.,

Fazekas, G., Nourhachemi, F., and Savoldelli, M.

(2012). Home deployment of a doubt removal tele-

care service for cognitively impaired elderly people:

A field deployment. In 3rd IEEE International Con-

ference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfo-

Com).

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., and Davis, F. D.

(2003). User acceptance of information technology:

Toward a unified view. MIS Q., 27(3):425–478.

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

126