Exergames for Assessment in Active and Healthy Aging

Emerging Trends and Potentialities

Evdokimos I. Konstantinidis, Panagiotis E. Antoniou and Panagiotis D. Bamidis

Lab of Medical Physics, Medical School, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

Keywords: Stealth Assessment, Exergames, Serious Game, Elderly Care Intervention, Physical Exercise.

Abstract: This paper articulated the position, based on literature research findings as well as experiences and

considerations, of the authors regarding the role of exergames in stealth cognitive assessment. The conclusions

presented therein are based on a long and lasting experience of design, implementation and piloting trials with

seniors over the last six years. They are also supported by literature findings concerning exergames’

engagement, acceptance, perceived usefulness and ease of use. The authors express a positive outlook

regarding the role of daily exergaming programs regarding their capacities in stealth assessment. Furthermore,

it is postulated that additional research efforts should focus on providing even more concrete, evidence based

arguments for convincing researchers and clinicians of the potential clinical value of exergames in terms of

cognitive assessment.

1 INTRODUCTION

Independent and healthy lifestyle of elderly

population has become an increasingly important

social issue, due to the increase of population age

across developed countries. It is documented that

regular physical activity is essential for healthy aging

(Chodzko-Zajko et al., 2009) in terms of physical

(Konstantinidis, Billis, et al., 2014) as well as

cognitive health (Lautenschlager et al., 2008;

Angevaren et al., 2008).

Exergames, which have been in focus of an

increasing number of research efforts, are technology

assisted solutions engaging the elderly in physical

exercise or activity through gaming. They aim to

motivate seniors to get involved in either physical

activity or physical exercise and, hence, promote a

more active lifestyle, through gaming

(Konstantinidis, Billis, et al., 2014). Towards this

end, the emergence of studies measuring exergaming

platforms’ usability for seniors led to proper design

implications, recommendations and guidelines for

exergames (Konstantinidis, Billis, et al., 2014).

Beyond the obvious physical benefits of exercise,

exergames demonstrated positive changes in mood

(Kirk et al., 2013; Gerling et al., 2012), socialization

(Gerling et al., 2011; Velazquez et al., 2013), and

confidence in everyday functional activities (Rendon

et al., 2012) as well as overall quality of life

improvement (Chodzko-Zajko et al., 2009;

Rosenberg et al., 2010).

Serious games for elders, which are games

designed for a primary purpose other than pure

entertainment aimed at a senior target group, focusing

either on cognitive or physical training, are deemed

either preventive/therapeutic interventions or

assessment oriented tools (McCallum, 2012).

Specifically, recent neuroscientific studies provided

increased evidence on the protective effects of

cognitive and physical training with regards to

cognitive decline and dementia (Bamidis et al., 2014).

On the other hand, serious games, especially

cognitive games, are considered as potential

assessment tools by emulating pen and paper

assessment tests (Hagler et al., 2014) or by

encapsulating cognitive tasks in a game-like interface

(Jimison et al., 2010; Jimison and Pavel, 2006;

Tarnanas et al., 2014). The integration of these

assessment techniques in the games, in a way that the

player is unaware of, is defined as stealth assessment

(Shute, 2011).

However, exergames only recently gained the

attention of researchers as cognitive status assessment

means. Virtual environments, simulations of daily

activities and daily usage exergames have just

emerged, exhibiting promising findings (Tarnanas et

al., 2013; Zygouris et al., 2014).

From the previous exposition it appears that the

325

I. Konstantinidis E., E. Antoniou P. and D. Bamidis P..

Exergames for Assessment in Active and Healthy Aging - Emerging Trends and Potentialities.

DOI: 10.5220/0005494503250330

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (SocialICT-2015),

pages 325-330

ISBN: 978-989-758-102-1

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

potential assessment aspect of exergames is only

starting to be investigated so far. There are not yet

design guidelines or even suggestions about

assessment through exergames, apart from the

general rule for successful assessment through

serious games: participation in the game.

On the other hand, the number of research efforts

on the assessment aspects of exergames is not large

enough to convince the research community for their

value in the field. Corresponding findings can be

deemed as indicators about the potential value of

exergames but not as evidence. Additionally, the role

of serious games has been debated over the last few

years. A large number of commercial or custom

exergaming platforms, which have been utilized by

seniors, are not tailored to them. Therefore, as it is

stated in previous work of the authors

(Konstantinidis, Billis, et al., 2014), they present a

significant learning overheads and entrance barrier

for the elderly users, which, in turn, reduces their

overall efficacy.

In line with this, Robert et al. reported poor

academic and professional acceptance of serious

games (Robert et al., 2014). This is based on the fact

that serious games are viewed by many researchers

and clinicians as expensive toys gaining no scientific

and clinical credibility (Anon, 2014). However, the

acceptance of serious games as tools for new

treatment options, is slowly starting to take root

(Robert et al., 2014).

In the following section (section 2) we present the

arguments about the value of exergames as stealth

assessment tools based both in the literature and in the

authors’ experience in the field. We close this work

in section 3 with some concluding remarks.

2 EXERGAMES FOR

ASSESSMENT

2.1 Exergames for Stealth Assessment

Aerobic exercises are presented as a promising tool

for physical health assessment in exergames by

measuring indirectly the caloric expenditure and heart

rate (Staiano and Calvert, 2011). In the same notion,

the perceived exertion scale (Borg, 1982) could

estimate the senior’s effort since it is directly

correlated with the heart rate. In addition, a large

research effort on assessment in exergames focuses

on fall risk. In-game performance metrics, like

movement and response time (Pisan et al.. 2013), step

length (Garcia et al.. 2012) and grip strength are used

towards fall risk assessment or even early signs

detection of frailty (Zavala-Ibarra and Favela. 2012).

Beyond physical status assessment, only recently,

exergames dealt with cognitive assessment. Virtual

environments (Tarnanas et al., 2013; Zygouris et al.,

2014) as well as daily usage exergames

(Konstantinidis et al., 2015) have recently turned

towards assessment. Some of these works correlated

significantly in-game metrics with standard clinical

screening and assessment tests. However, it should be

kept in mind that the nature of these games requires

extra effort towards cognitive assessment rather than

physical status assessment.

2.2 Exergames Are More Engaging

than Cognitive Games, Thus More

Efficient for Stealth Assessment

Participation to serious games is the main rule for

successful assessment. According to the technology

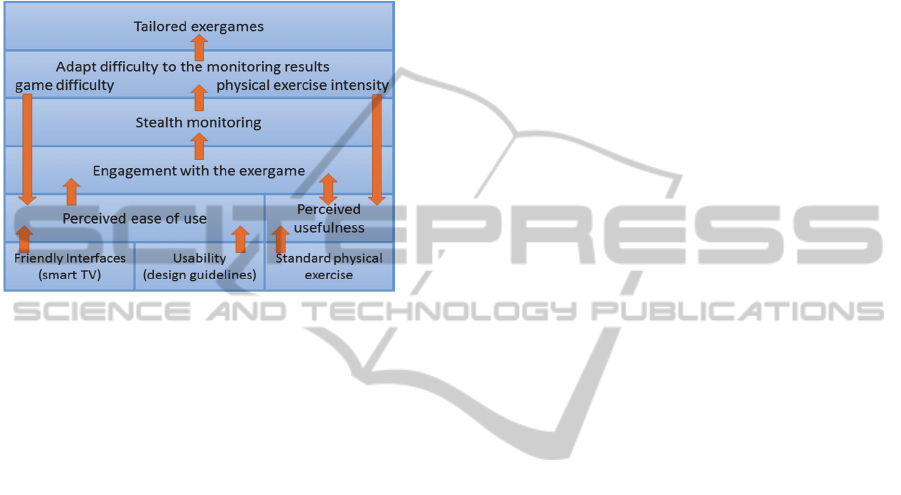

acceptance model (Davis, 1989), which has been

developed to explain ICT use, perceived usefulness

(PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) are the

primary determinants that affect use attitude.

Therefore, the fact that physical exercise’s effects are

observable by the seniors after a very short period of

training, in conjunction with the immediate positive

mood changes after physical activity (Kirk et al.,

2013; Pierce and Pate, 1994; King et al., 2000),

emerge the potential of a strong perceived usefulness

factor of exergames (c.f. Figure 1).

The authors’ experience concurs with that. Wide

pilot trials, in terms of time (2 months) and

participants (116 seniors), of the FitForAll

(Konstantinidis, Billis, et al., 2014) platform

demonstrated this. This platform encapsulated the

American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and

the American Heart Association (AHA) protocols,

guidelines and recommendations regarding the exact

type and intensity of elderly exercise regimens

(Chodzko-Zajko et al., 2009). The pre- and post-

intervention Fullerton physical status assessment

provided clear evidence that integration of these

recommendations led to an overall physical status

improvement of the seniors. Besides that, the vast

majority of the participants reported that they felt

their body more light weighted, increased sleep

quality and that they performed daily activities with

greater flexibility even after a small period of

exergaming sessions. Most of them reported that

although they had felt bored to follow an exergaming

regimen before participating in the first sessions, they

were happy to follow the daily regimen. Seniors’

adherence to the daily schedule, and thus to the

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

326

physical exercise protocol schedule, reached 82%.

Moreover, 85.4% of the seniors reported that they

perceived the FFA platform as allowing them to

control their health better. Thus, the incorporation of

existing, established physical exercises during design

and implementation of exergames could serve as an

additional guideline for their design.

On the cognitive games axis, the effects in

cognitive function, could be observed only after long

term training. As an indicative example, Minge et al.

reported the results of a focus group among seniors

where serious games were rated as possibly helpful

(Minge et al., 2014). To this end, authors observed

that seniors tend to undertake cognitive games

because they have been told that they are helpful for

their cognition contrary to exergames of which the

effects are immediately observable in their daily life.

Some of the seniors’ response when they were asked

about exergames, were: “Better mobility. It helped me

with the pain on my back and on my joints. I lost

weight. I fall asleep more easily”. When they were

asked regarding the cognitive games they responded:

“I like these games because they will help my

memory. I believe that they will help me against

dementia”. This delayed emergence of cognitive

games’ perceived effects (as denoted by the

testimonials’ future tense and qualifiers) may not be

able to sustain the initial games’ engaging factor

introducing a larger dropout risk since the participants

might not reach the time threshold of its perceived

usefulness. On the contrary, exergames’ more

immediate effects could be complementary to the

initial motivation which stems from the joyful

experience of the “gaming” component

(Konstantinidis, Billis, et al., 2014; Brox et al., 2011;

Shubert 2010). Finally, there is a trade-off on the

efficiency for stealth assessment (exergames) and the

accuracy of stealth assessment (cognitive games).

2.3 Exergames Acceptance and

Participation

Regarding perceived ease of use, recent technological

advances and services that support controllers utilized

by exergames (e.g. Kinect, Balanceboard, etc.)

(Konstantinidis, Antoniou, et al., 2014), led to rich

internet applications available to contemporary

devices like SmartTV, tablets and smartphones.

Studies have shown that these devices are far more

useful to elderly users for access to internet based

services (Werner et al., 2012). Moreover, the ease of

access provided by these devices, far outweighs the

lack of versatility in comparison with traditional

computer systems. Therefore, barriers in participating

to exergames due to technology constraints (PC

usage, etc.) have been lifted in the last years. More

specifically, the Kinect smart TV combination could

be deemed as a natural interface for exergaming. To

the authors’ experience (Konstantinidis, Billis, et al.,

2014), the seniors reported that 5 days familiarization

with the exergaming platform were enough for

feeling that have mastered the platform. On the other

hand, when the exergames utilized by the seniors by

means of Kinect gestures and postures through a

smart TV, the seniors reported that they needed 4

days for the same feeling.

2.4 Carefully Designed Features

Increase Stealth Assessment

Quality and Accuracy

The authors’ experience during the design and

implementation of FitForAll as well as during the

intervention trials, the data analysis and the literature

research led to a number of design recommendations

for exergames which have bearing on assessment.

Designing and incorporating proper in-game

stealth assessment is a challenging (Bellotti et

al., 2013) process. However, the value of its

outcome denotes it as a promising component

of serious games and justifies the extra effort.

Exergames should be tailored to the elders in

order to secure increased adherence.

When serious games are utilized for assessment

of elders not familiar with the technology, a

short learning period is required. Assessment

during this period reflects also familiarization

and initial perception of components.

High resolution monitoring, incorporating as

much as reasonably acquirable information as

possible, provides opportunities for data

mining towards new design recommendations.

Exergames could incorporate games that

motivate users to perform tasks identical to

those in standard assessment tests both in the

cognitive and in the physical domain

Cognitive tasks should be required during

exergames but without overloading the elders.

Open policies for exergaming data

accompanied by semantic markup have to be

provisioned inherently in future research.

Twin scope exergames, focusing both to

prevention and assessment, is feasible. A

game’s daily session could be divided in long

training periods and short assessment periods

with less physical intensity (focus on cognitive

assessment) so as to avoid cognitive overload

ExergamesforAssessmentinActiveandHealthyAging-EmergingTrendsandPotentialities

327

and to prevent overexertion and wrong pacing

(Gerling et al., 2012).

A very simple assessment task, which could be

representative of the elders’ daily mood and

cognitive function (e.g. reaction time), should

be included in the beginning of the serious

game in order to provide a baseline for each

daily session.

Figure 1: Perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness

are greatly affected by the exergame’s interface and its

physical exercise intensity. Both of these factors have to be

tailored to the seniors in order to ensure engagement with

the game and consequently stealth monitoring.

2.5 Screening Games versus

Exergames

Virtual environments have entered in the field of the

cognitive assessment. Walking on a treadmill

visualized as a stroll in a virtual environment

(Tarnanas et al., 2013; Tarnanas et al., 2014), or

trying to accomplish some daily tasks (Zygouris et al.,

2014), were exploited as screening games with

promising results as such. However, the very fact that

these games are administered as screening games and

not as daily usage games may open them to the same

vulnerabilities as conventional clinical assessment.

Clinical cognitive screening is not part of the elder’s

lifestyle (Jimison et al., 2010). Besides this, seniors

have strong motivation to do well on cognitive

screening tests, to prove that they are not suffering

from cognitive decline, to avoid social stigma

(McKanna et al., 2009). Moreover, day to day

variations in performance can confuse the diagnosis

for a significant time periods (McKanna et al., 2009).

Contrary to that, as discussed above, exergames

are adoptable by seniors in daily life. Due to that

temporal immediacy, the aforementioned vulnerable

points are negated. There is, of course, a trade-off on

the accuracy of the cognitive assessment of

exergames which is undergoing research. Preliminary

results of the authors’ work reveals a classification

accuracy among healthy, people with mild cognitive

impairment and mild dementia over 70%

(Konstantinidis et al., 2015). This accuracy level,

with respect of the fact that the seniors did not

consider exergames as monitoring tool (Antoniou et

al., 2015), turn out to be a promising combination in

accordance with the Plato’s statement “...you can

discover more about a person in an hour of play than

in a year of conversation...”.

2.6 Exergames in Light of Healthcare

Cost Reduction

The absence of an effective treatment against

cognitive decline denotes the early administration of

the available treatments as the more efficient

approach (Gauthier, 2005). An unobtrusive and low

cost tool that could contribute to early detection of

cognitive decline symptoms could provide

opportunities for early administration of available

treatments at a time that they may be more effective

(Jimison and Pavel, 2006). Such a system could

contribute to the delay of cognitive decline onset,

since it is already well documented that physical

exercise is a preventive intervention for it (Bamidis et

al., 2014). Moreover, exergames that could be used

by the seniors themselves in their home would

contribute to the insurances’ and public healthcare

system’s cost reduction (Robert et al., 2014). To this

end, the financial benefits and costs of serious games

with prevention and screening aspects must be

measured in conjunction to the value of timely and

correct diagnosis (Borson et al., 2013).

3 CONCLUSIONS

This position paper aims to provide some food for

thought about exergames and their role in cognitive

assessment in conjunction with their primary scope

which is physical training. Both literature findings

and the authors’ experience substantiate the claim that

exergames will continue to remain in the focus of

research within the next decade. Additional research

efforts should be put on providing evidence based

arguments for researchers and clinicians about the

potential clinical value of the exergames as means of

assessment.

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

328

REFERENCES

Angevaren, M. et al., 2008. Physical activity and enhanced

fitness to improve cognitive function in older people

without known cognitive impairment. The Cochrane

database of systematic reviews, (3), p.CD005381.

Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/

18646126 (Accessed February 10, 2015).

Anon, 2014. “A Consensus on the Brain Training Industry

from the Scientific Community,” Max Planck Institute

for Human Development and Stanford Center on

Longevity. Available at: http://longevity3.stanford.edu/

blog/2014/10/15/the-consensus-on-the-brain-training-

industry-from-the-scientific-community/ (Accessed

February 11, 2015).

Antoniou, P.E. et al., 2015. Instrumenting the eHome and

preparing elderly Pilots - the USEFIL approach. In P.

D. Bamidis et al., eds. Innovations in the Diagnosis and

Treatment of Dementia.

Bamidis, P.D. et al., 2014. A review of physical and

cognitive interventions in aging. Neuroscience and

biobehavioral reviews. Available at: http://www.

sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0149763414000

75X.

Bellotti, F. et al., 2013. Assessment in and of Serious

Games: an overview. Advances in Human-Computer

Interaction, 2013, p.1. Available at:

http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2484486 (Accessed

June 6, 2014).

Borg, G.A.G., 1982. Psychophysical bases of perceived

exertion. Med sci sports exerc. Available at:

http://fcesoftware.com/images/15_Perceived_Exertion.

pdf (Accessed June 18, 2014).

Borson, S. et al., 2013. Improving dementia care: the role

of screening and detection of cognitive impairment.

Alzheimer’s & dementia : The journal of the

Alzheimer's Association, 9(2), pp.151–9. Available at:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S155

2526012025009 (Accessed August 29, 2014).

Brox, E. et al., 2011. Exergames for elderly: Social

exergames to persuade seniors to increase physical

activity. In Pervasive Computing Technologies for

Healthcare (PervasiveHealth), 2011 5th International

Conference on. IEEE, pp. 546–549.

Chodzko-Zajko, W.J. et al., 2009. American College of

Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical

activity for older adults. Medicine and science in sports

and exercise, 41(7), pp.1510–30. Available at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19516148

(Accessed January 20, 2014).

Davis, F.D., 1989. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of

use, and user acceptance of information technology.

MIS quarterly, pp.319–340.

Garcia, J.A. et al., 2012. Exergames for the elderly: towards

an embedded Kinect-based clinical test of falls risk.

Studies in health technology and informatics, 178,

pp.51–7. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

pubmed/22797019 (Accessed May 30, 2014).

Gauthier, S.G., 2005. Alzheimer’s disease: the benefits of

early treatment. European journal of neurology : the

official journal of the European Federation of

Neurological Societies, 12 Suppl 3, pp.11–6.

Available

at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16144532

(Accessed September 15, 2014).

Gerling, K. et al., 2012. Full-body motion-based game

interaction for older adults. In Proceedings of the

SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press, pp.

1873–1882.

Gerling, K.M., Schulte, F.P. & Masuch, M., 2011.

Designing and evaluating digital games for frail elderly

persons. In Proceedings of the 8th International

Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment

Technology. ACM, p. 62.

Hagler, S., Jimison, H. & Pavel, M., 2014. Assessing

Executive Function Using a Computer Game:

Computational Modeling of Cognitive Processes. IEEE

Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, 18(4),

pp.1442–1452. Available at: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/

lpdocs/ epic03/ wrapper.htm?arnumber=6732879

(Accessed July 1, 2014).

Jimison, H. & Pavel, M., 2006. Embedded Assessment

Algorithms within Home-Based Cognitive Computer

Game Exercises for Elders. In 2006 International

Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and

Biology Society. IEEE, pp. 6101–6104. Available at:

http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/lpdocs/epic03/wrapper.htm?

arnumber=4463200 (Accessed July 2, 2014).

Jimison, H.B. et al., 2010. Models of cognitive performance

based on home monitoring data. Conference

proceedings : Annual International Conference of the

IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society.

IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology

Society. Conference, 2010, pp.5234–7. Available

at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/ pubmed/ 21096045

(Accessed July 2, 2014).

King, A.C. et al., 2000. Comparative effects of two physical

activity programs on measured andperceived physical

functioning and other health-related quality of

lifeoutcomes in older adults. The Journals of

Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical

Sciences, 55(2), pp.M74–M83. Available at:

http://biomedgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/content/5

5/2/M74.short (Accessed February 11, 2015).

Kirk, A. et al., 2013. An Exploratory Study Examining the

Appropriateness and Potential Benefit of the Nintendo

Wii as a Physical Activity Tool in Adults Aged≥ 55

Years. Interacting with Computers, 25(1), pp.102–114.

Konstantinidis, E.I., Antoniou, P.E., et al., 2014. A

lightweight framework for transparent cross platform

communication of controller data in ambient assisted

living environments. Information Sciences, 300,

pp.124–139. Available at: http://www.

sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0020025514011

906 (Accessed January 7, 2015).

Konstantinidis, E.I., Billis, A.S., et al., 2014. Design,

implementation and wide pilot deployment of

FitForAll: an easy to use exergaming platform

improving physical fitness and life quality of senior

citizens. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health

ExergamesforAssessmentinActiveandHealthyAging-EmergingTrendsandPotentialities

329

Informatics, pp.1–1. Available at:

http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/articleDetails.jsp?arnumber=

6980053 (Accessed December 10, 2014).

Konstantinidis, E.I. et al., 2015. In-game metrics as a tool

for the cognitive assessment of the elderly. Evidence

from extended trials with the FitForAll exergame

platform. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, Submitted.

Lautenschlager, N.T. et al., 2008. Effect of physical activity

on cognitive function in older adults at risk for

Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA, 300(9),

pp.1027–37. Available at: http://jama.jamanetwork.

com/article.aspx?articleid=182502 (Accessed February

10, 2015).

McCallum, S., 2012. Gamification and serious games for

personalized health. Studies in health technology and

informatics. Available at: http://www.google.com/

books?hl= en&lr=&id=cqwQfyrD-oYC&oi=fnd&pg=

PA85&dq=gamification+and+serious+games+for+per

sonalized+health&ots=xLLZKzgRsa&sig=HAQlkED

1TayFIFe3V6YjPcc6oLw (Accessed June 6, 2014).

McKanna, J.A., Jimison, H. & Pavel, M., 2009. Divided

attention in computer game play: analysis utilizing

unobtrusive health monitoring. In Conference

proceedings : ... Annual International Conference of the

IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society.

IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society.

Conference. pp. 6247–50. Available at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19965090

(Accessed June 6, 2014).

Minge, M., Bürglen, J. & Cymek, D.H., 2014. Exploring

the Potential of Gameful Interaction Design of ICT for

the Elderly. In HCI International 2014-Posters’

Extended Abstracts. Springer, pp. 304–309.

Pierce, E.F. & Pate, D.W., 1994. Mood alterations in older

adults following acute exercise. Perceptual and motor

skills, 79(1 Pt 1), pp.191–4. Available at:

http://www.amsciepub.com/doi/abs/10.2466/pms.1994

.79.1.191?journalCode=pms (Accessed February 11,

2015).

Pisan, Y., Marin, J.J.G. & Navarro, K.F.K., 2013.

Improving lives: using Microsoft Kinect to predict the

loss of balance for elderly users under cognitive load.

In Proceedings of The 9th Australasian Conference on

Interactive Entertainment Matters of Life and Death -

IE ’13. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press, pp. 1–

4. Available at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?

id=2513026 (Accessed February 7, 2014).

Rendon, A.A. et al., 2012. The effect of virtual reality

gaming on dynamic balance in older adults. Age and

ageing, 41(4), pp.549–52. Available at: http://ageing.

oxfordjournals.org/content/41/4/549.short (Accessed

February 11, 2014).

Robert, P.H. et al., 2014. Recommendations for the use of

Serious Games in people with Alzheimer’s Disease,

related disorders and frailty. Frontiers in Aging

Neuroscience, 6, p.54. Available at:

http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?a

rtid=3970032&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract

(Accessed April 4, 2014).

Rosenberg, D. et al., 2010. Exergames for subsyndromal

depression in older adults: a pilot study of a novel

intervention. The American journal of geriatric

psychiatry : official journal of the American

Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(3), pp.221–6.

Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/

articlerender.fcgi?artid=2827817&tool=pmcentrez&re

ndertype=abstract (Accessed January 27, 2014).

Shubert, T.E., 2010. The use of commercial health video

games to promote physical activity in older adults.

Annals of Long-Term Care, 18(5), pp.27–32.

Shute, V.J., 2011. Stealth assessment in computer-based

games to support learning. Computer games and

instruction, 55(2), pp.503–524.

Staiano, A.E. & Calvert, S.L., 2011. The promise of

exergames as tools to measure physical health.

Entertainment computing, 2(1), pp.17–21. Available at:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187

5952111000188 (Accessed March 30, 2014).

Tarnanas, I. et al., 2014. Can a novel computerized

cognitive screening test provide additional information

for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease? Alzheimer’s

& dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association.

Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.

com /science/ article/ pii/ S155252601400003X

(Accessed October 9, 2014).

Tarnanas, I., Schlee, W. & Tsolaki, M., 2013. Ecological

validity of virtual reality daily living activities

screening for early dementia: longitudinal study. JMIR

Serious Games, 1(1), pp.16–29. Available at:

http://games.jmir.org/2013/1/e1/ (Accessed July 8,

2014).

Velazquez, A. et al., 2013. Design of exergames with the

collaborative participation of older adults. In

Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 17th International

Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work

in Design (CSCWD). IEEE, pp. 521–526.

Werner, F., Werner, K. & Oberzaucher, J., 2012. Tablets

for Seniors–An Evaluation of a Current Model (iPad).

In Ambient Assisted Living. Springer, pp. 177–184.

Zavala-Ibarra, I. & Favela, J., 2012. Ambient Videogames

for Health Monitoring in Older Adults. In 2012 Eighth

International Conference on Intelligent Environments.

IEEE, pp. 27–33. Available at: http://ieeexplore.

ieee.org/lpdocs/epic03/wrapper.htm?arnumber=62584

99 (Accessed June 6, 201).

Zygouris, S. et al., 2014. Can a Virtual Reality Cognitive

Training Application Fulfill a Dual Role? Using the

Virtual Supermarket Cognitive Training Application as

a Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment.

Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

330