The Whole Is More than the Sum of Its Parts

On Culture in Education and Educational Culture

Thomas Richter and Heimo H. Adelsberger

TELIT, University of Duisburg-Essen, Universitätsstrasse 9, Essen, Germany

Keywords: e-Learning, Inclusion, Culture Awareness, Culture-Sensible Education, Educational Culture, Culture-

Related Conflicts in Education, Learning Culture Survey.

Abstract: The Learning Culture Survey investigates learners’ expectations towards and perceptions of education on

international level with the aim to make culture in the context of education better understandable and sup-

port educators to prevent and solve intercultural conflicts in education. So far, we found that culture-related

expectations differ between educational settings, depend on the age of the learners, and that a nationally

homogenous educational culture is rather an exception than the rule. The results of our recently completed

longitudinal study provided evidence that educational culture on the institutional level actually is persistent,

at least over a term of four years. After a brief introduction of the general background, we will subsume the

steps taken during the past seven years and achieved general insights regarding educational culture. Last, we

will introduce a method for the determination of conflict potential, which bases on the understanding of cul-

ture as the level to which people within a society accept deviations from the usual. We close with demon-

strating the method’s functionality on examples from the Learning Culture Survey.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the increasing internationalization of class-

rooms and the distribution of e-Learning programs

and content through the Internet, a better under-

standing of the role of culture in education gets in-

dispensible. Reports of increasing numbers of early

school leavers and dropouts in universities accumu-

late which mainly concern learners with a migration

rofessional training were not seen as respece respon-

sponsibility of the learners to adapt the given condi-

tions of their learning context, but the educational

institutions’ duty to ensure that an environment is

provided which leads to productive learning for any

kind and type of learner (Haberman, 1995). Even es-

tablished e-Learning providers rather waive the

chance to attract a higher number of learners and

stick to their local markets, instead of risking unsat-

isfied learners because of unforeseen cultural con-

flicts (Richter and Adelsberger, 2011). Meanwhile,

in support of finding solutions, the EC defined a re-

lated key issue for the 2015-call for project pro-

posals in their Erasmus-Plus program.

In his study, Nilsen (2006) found that the main

reasons for students’ dropping out were ineffective

study strategies, a mismatch between expectations

and content in the study program, and a lack of mo-

tivation. Bowman (2007) even claims that strong ef-

forts should be made in order not to ’destroy’ the

initial motivation by confronting the learners with

unnecessary conflicts. So far, we know that besides

language gaps and content-related issues, the learn-

ers’ motivation is threatened by unmet expectations

and not understandable regulations, arising from cul-

ture-specific differences between their origin and the

new context.

In e-Learning scenarios, a constantly high level

of motivation is the most crucial success factor

(Richter and Adelsberger, 2011). If learners lose

their motivation in a face-to-face scenario, the edu-

cator still has a chance to recognize that and can

support the regain of motivation (Rothkrantz et al.,

2009). In e-Learning scenarios, this chance rarely is

given; without recognizing the learners’ mimics and

gestures as tools to communicate frustration (Sanda-

nayake and Madurapperuma, 2011), the instructors

depend on explicit communication, which often does

not happen due to cultural reasons.

The Learning Culture Survey investigates learn-

ers’ perceptions in different national and regional

contexts and aims to support educators to better un-

derstand educational culture in general and cultural

differences between specific educational contexts, in

particular. Such an understanding is relevant for the

372

Richter T. and H. Adelsberger H..

The Whole Is More than the Sum of Its Parts - On Culture in Education and Educational Culture.

DOI: 10.5220/0005498103720382

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 372-382

ISBN: 978-989-758-108-3

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

development of culture-sensitive education. We fur-

ther on aim to support both learners and educators in

their preparation efforts when planning to study or

teach in other countries.

2 THE LEARNING CULTURE

SURVEY (LCS)

In the following we distinguish between “culture in

education”, which is used as a general term, without

a direct relation to a particular context, “educational

culture”, which is used when a specific context is re-

ferred to and “learning culture”, which is related to

perceptions of and attitudes towards education from

the perspective of the learners.

Today’s applied comparative culture research

mostly refers to culture as persistent value-driven

perceptions and attitudes, which, amongst all people

within national societies are homogenously favoured

or refused (literature reviews from, e. g., Jones,

2007; Leidner and Kayworth, 2006). Geert Hofstede

(1980), as a pioneer (Smith, 2006) and still, one of

the central proponents of this “etic” concept for cul-

ture research, speaks of culture as the “Software of

the Mind” which goes back to Montesquieu’s “spirit

of a nation” (18

th

century). In his research, Hofstede

initially found four cultural dimensions (later on,

two more dimensions followed), which focused on

basic values and classified around 40 nations

through specific key values per dimension. Follow-

ing Hofstede’s demonstrated examples (Hofstede,

Hofstede, and Minkow, 2010), it is possible to pre-

dict and compare the relative cultural distance be-

tween two nations according to concrete attitudes

and perceptions that are related to each of the di-

mensions. In other words, according to the results,

people from one nation are considered more likely to

act or react in a certain way than those of another na-

tion. Köppel (2002) suggests that one reason for the

persistent high level of popularity of this approach

lies in its’ simplicity. Alongside its achieved promi-

nence, Hofstede’s Dimensions Model has constantly

been challenged and criticized on methodological,

interpretational, and ethical levels (e. g., Douglas

and Liu, 2011; Jones, 2007; Leidner and Kayworth,

2006; Tarras and Steel, 2009).

Several further reasons than the already found

points of criticism affirmed our own doubts if the

national values from Hofstedes’ dimensions model

and the concept of a general national culture would

appropriately reflect culture in education. For the

context of culture in education, we initially decided

to adopt the majority-based and group-related cul-

ture definition of Oetting (1993), who suggests to

use the term ‘to describe the customs, beliefs, social

structure, and activities of any group of people who

share a common identification and who would label

themselves as members of that group’. We could not

imagine that basic values exclusively should be re-

sponsible for educational culture. According to our

own practical experiences from the fields of school

education, Higher Education, and professional train-

ing, we saw significant differences between their

modi operandi, which did not necessarily reflect

basic values or national cultures at all.

Another reason for doubts regarding the applica-

bility of Hofstede’s dimensions model in the context

of educational culture resulted from the reported ex-

periences from Mitra et al. (2005) which later on

were confirmed by Buehler et al. (2012): Both re-

search groups found that the children in their studies

below an age of twelve years acted quite differently

from older children as they rather followed their cu-

riosity than the assumed cultural biasing. Last, we

were unsure if the culture within educational institu-

tions actually stays persistent over time after chang-

es regarding basic conditions took place.

2.1 LCS:

Operationalization

Besides a cross-disciplinary literature review on re-

ported conflicts in education and culture research in

general, we conducted qualitative pre-studies involv-

ing university students and educators. In the con-

ducted (informal) interviews, we asked them for

perceived cultural conflicts during their times of

studying abroad and related to other (foreign) stu-

dents within the home university. The first version

of our questionnaire considered both the reported

conflicts in education from the literature and issues

that arose from the interviews.

The questionnaire was designed for the context

of Higher Education and originally consisted of 128

items related to the following aspects of education

(Richter, 2011):

Role, responsibilities, and tasks of lecturers

Feedback

Motivation

Gender issues

Several aspects of group work

Time management

Role, responsibilities, and tasks of tutors

Demographic data

TheWholeIsMorethantheSumofItsParts-OnCultureinEducationandEducationalCulture

373

For recognition, the full questionnaire has per-

manently been published in English language under

the DOI: 10.13140/2.1.2877.5206 (Richter, 2014).

In 2009, we decided to start with our investiga-

tion within the only two national contexts, which

Müller et al. (2000) found to having more or less

culturally homogenous populations, i. e., Germany

and South Korea. These two national contexts con-

veniently also appeared perfectly suitable for the ini-

tial study because of their generally very different

educational systems and traditions.

Before the implementation took place, the ques-

tionnaire was translated to German and Korean.

Several test studies and refinement cycles were ap-

plied in both contexts in order to ensure its’ compre-

hensibility and appropriateness. The students per-

ceived some of the originally included statements as

confusing and some others even as irritating. Re-

garding socially sensible topics, we had to expect

that the students would rather provide socially ac-

ceptable answers than expressing their actual opin-

ions; even though the respondents were considered

to stay anonymous. Thus, we removed related items

and reformulated others. In the end, 102 items re-

mained for the initialization of the field study.

For most of the items, we applied a 4-point Lik-

ert Scale. We wanted to force the respondents to

take a position instead of giving them the chance to

choose a neutral response option (Garland, 1991).

Our aim was to design a standardized questionnaire,

reusable in later steps within any context in the same

form (just translated to local languages). For future

contexts, we had to expect that items might not ap-

ply in the same measure as experienced in the test

studies. Thus, we provided an additional answer-

option, which was “not applicable in my context”.

We visually separated this option from the main

scale in order to avoid that respondents misinterpret

it as an integral part of the general answer options.

The strategy of separated positioning worked out

well: In later studies, this option rarely was used.

2.2 Evaluation and Interpretation

As only criterion for the evaluation, we decided to

exclusively accept fully completed questionnaires

including both the items that had to be evaluated and

(most of) the demographic data.

From our investigated contexts, we received very

different sample sizes, which, in the original design

of the scale, would not have been comparable

amongst each other because of the extreme values’

different impacts on the full samples. In order to

solve this problem, we followed the recommenda-

tion of Baur (2008: 282) and binarized our results

for the contrasting across contexts in positive and

negative answers. Baur particularly recommends the

binarising of ordinal-scaled results in order to pro-

duce clearer results and prepare ordinal-scaled data

for operations that originally are reserved for inter-

val-scaled data. There is a controversial discussion

on applying higher-level statistical methods to ordi-

nal-scaled data (Knapp, 1989). We followed the rec-

ommendation of Porst (2008) to case-sensitively

check the results for appropriateness, which, in our

case, revealed inconsistent results when calculating

variance, co-variance and standard deviation. In con-

trast, the calculated mean was sound between the 40-

and 60-quantiles and thus, usable to provide infor-

mation on the answer distributions, which else

would have been lost after the binarising process.

When directly contrasting results across contexts, we

focused on the percentage of positive answers.

For the decision if a result regarding a certain

item actually reflects culturally motivated or rather

individual preferences of the students, we generally

assumed that if we find a clear tendency to rejection

or acceptance (negative/positive), the answer was

culturally motivated, else, individually. As a clear

tendency, we defined everything below 40% positive

answers as rejection and everything above 60% posi-

tive answers as acceptance. All items evaluated be-

tween 40% and 60% positive answers were assumed

to be too close to an equal distribution and thus,

probably expressing individual preferences. We

chose such a large interval as our “fuzzy area” be-

cause in our context of learning culture, we had to

deal with opinions of people on aspects of life,

which at least to a large part were not substantial for

the respondents’ survival or the general functioning

of societies. On individual level, such types of opin-

ions easily could be changed from one to another

moment. Moreover, we did not know if our results

would reveal persistent over time on the large scale.

We cannot clearly determine if the individual re-

sponses of the participants in our study are driven by

desires (what they wish to be) or the status quo

(what they expect to be due to prior experiences). In

retrospective and for most cases, the results are quite

clearly showing that the students evaluated accord-

ing to their experiences.

2.3 Implementation

As for the first wave of our large-scale implementa-

tion, we found very different conditions in the con-

texts of Higher Education in Germany and in South

Korea.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

374

In Germany, we were able to address the entire

student populations of three universities by using our

online questionnaire, i. e., the University of Co-

logne, the University of Applied Sciences Bonn-

Rhein-Sieg, and the University of Potsdam. Each of

the university-administrations sent the invitation for

participation to all of their registered students

through their internal E-Mail distribution system.

The response rates were between 2-6% for each uni-

versity and confirmed the usual experiences for re-

sponse rates in online questionnaires. In total, from

the three universities, 3225 students started answer-

ing and 1817 students left fully completed question-

naires. The distribution between female and male

students was 544/1268 (five students used the option

“other”).

In the context of Higher Education in South Ko-

rea, we did not have the opportunity to use the

online survey within the universities due to legal is-

sues but instead, had to collect the data “on the

street”, using the paper-based version. In order to

still receive something close to random samples, we

followed the suggestion of Kromrey (2006) and

chose our respondents on the basis of a random-

route algorithm. More than 50% of the Korean popu-

lation lives in and around Seoul. The city has more

than 50 universities and a subway system, which

links the suburbs and close cities with each other.

Thus, we limited our investigation to this city. Due

to permanent traffic jam and uncomfortable parking

situations, Korean students usually and frequently

use the subway. Because of these characteristics, we

eventually decided to conduct our survey in the

subway and predefined a fixed algorithm where to

enter the subway and how to decide which persons

were to be invited for participation: Go down the

main entrance to the gate, take the first wagon en-

trance available on your right side and ask all people

that appear to have an age between 18 and 30 (start-

ing on your right side and going around in this wag-

on) if they currently are university students, at least

have six further stations to go, and are willed to par-

ticipate in our survey. After completion of one

round, leave the subway on the next stop where an-

other line crosses its way and change the subway

line. If possible, follow the direction to the centre. In

order to involve a high number of subway lines (and

thus, catch students on their way to different univer-

sities), we started with the only available round-line

in the city and randomly changed the initial entry

point each day. The condition regarding the six fur-

ther stations was related to the average time required

to complete the questionnaire. Most participants in

the German sample (which ended before the Korean

study) needed 11-15 minutes for the completion of

the online questionnaire. The subway trains in Seoul

take about three minutes from one to another station.

We calculated that 18 minutes should be enough to

introduce how to proceed (no long considerations

but intuitive and quick answering), hand out the ma-

terial, let them complete the questionnaire, and col-

lect the results; in most cases, this calculation

worked. For most people, sitting in the subway is

boring and so, we achieved a response-rate of 50%

(counting just persons claiming to be university stu-

dents). We had three weeks for the data collection,

and received 286 fully completed paper-based ques-

tionnaires with a relationship between female and

male students of 153/131 (two students selected

“other”). 58 of the “delivered” questionnaires had to

be rejected because relevant items were left unan-

swered. The students within the sample studied at 39

universities. From nine universities, we received

nine and more completed questionnaires.

The received data-sets with many sample ele-

ments per university from the German sample were

predestined to drive an in-depth analysis by compar-

ing the data not just on university but also on faculty

level. The Korean sample, in contrast, was well suit-

able for a broad analysis on university level.

We were not yet able to determine if the found

educational cultures from Higher Education would

be transferable to other educational contexts. In the

end of 2011, we conducted small-scale studies in

five randomly selected enterprises for that purpose:

We randomly chose them from the list of stock-

noted enterprises (DAX), which provide in-house

training. Five enterprises eventually granted their

participation. However, we were restricted to in-

volve a maximum of 25 participants per enterprise.

Apart of defining the condition that the selected em-

ployees should work in positions, in which they ac-

tually are meant to participate in the provided in-

house trainings, we had no further influence on who

exactly would be invited; this was an internal deci-

sion. As a result, we received seven and more re-

sponses just from two of the five enterprises. How-

ever, the results from these two enterprises eventual-

ly revealed sound because in relevant aspects, they

reflected the specific characteristics of the enterpris-

es’ organizational cultures’ and the age and positions

of the participating employees. For this study, we

slightly modified the used terminology in our ques-

tionnaire. As an example, we changed the term “pro-

fessor/lecturer” to “instructor”.

Between 2012 and 2013, we received further

translations of the questionnaire to Bulgarian, Chi-

nese (simplified and traditional), French, Greek,

TheWholeIsMorethantheSumofItsParts-OnCultureinEducationandEducationalCulture

375

Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, and Turkish. With

the support of guest students, we drove test studies

in their home countries, which were Bulgaria (30

sample elements), Ukraine (53), Turkey (40), and

British (30) and French (25) Cameroon. These re-

sults surely were not representative for each of the

countries’ contexts of Higher Education but provid-

ed first impressions of what we could expect in

large-size investigations. In the summer of 2014, we

completed another large-size study (online) at the

university of Accra in Ghana with 306 fully com-

pleted questionnaires (response rate around 3% and

female/male relationship 126/177). In the end of the

year, we started the implementation of the LCS

online-survey in France. The study in France is on-

going since we yet just managed to involve a single

university with limited access to the students (so far,

we received 75 fully completed responses).

Also in the end of 2014, we were able to repeat

our investigation in one of the German universities,

namely the University of Applied Sciences Bonn-

Rhein-Sieg. The questionnaire, again, was imple-

mented as online survey, and all registered students

were invited by the administration using the internal

E-Mail distribution system. The investigation served

two purposes, first, to find out if the educational cul-

ture in this university generally kept persistent over

the past years, and second, if the immense logistic

and personnel changes that had taken place in the

meantime were reflected in the results. The Univer-

sity of Applied Sciences Bonn-Rhein-Sieg still is a

quite young and relatively small university. It is con-

stantly expanding on all levels, regarding offered

subjects to study, employed professors and staff, and

infrastructure. In order to achieve meaningful results

with a repetitive investigation, we at least had to

wait three years in order to ensure that the prior in-

vestigated generation of students (Bachelor and

Master) were completely substituted through new

students; else, we would have risked to receive data

that reflected the memory of students instead of the

status quo. Anyways, a very low number of students

still remained because, after having finalized their

Bachelor degrees, they started studying in a Master

program. However, the number of students per year

who are accepted to enter the Master programs is

very limited in this university and the entry condi-

tions are challenging. In the repetitive study, we re-

ceived 375 fully completed questionnaires, which is

6,6% of the whole student population (5621). The

relationship between female and male respondents

was 166/208 (one student decided for “other”).

3 FINDINGS ON LEARNING AND

EDUCATIONAL CULTURE

With our data, we were able to answer most of our

beforehand open general questions of educational

culture. In the following, the findings are discussed

in detail and separated by category.

We use net diagrams for the visualization of the

results from two or more contexts. Each diagram is

related to a thematic block, like for example “Tasks

of the Lecturer”. We consider all items within the

same thematic block to being directly related

amongst each other. In the diagrams, we only dis-

play the results according to the found percentage of

positive answers. Since the option “Not applicable in

my context” has really been used (below 1%), the

rest of the answers can be expected to be rejections.

Please note that displaying the data in this way is

meant to facilitate the recognition of differences be-

tween contexts, to some extent, eye-candy, but only

the crossing points on each of the axes of the dia-

grams actually represent defined values.

3.1 Learning Culture in Faculties

The German samples were large enough to analyse

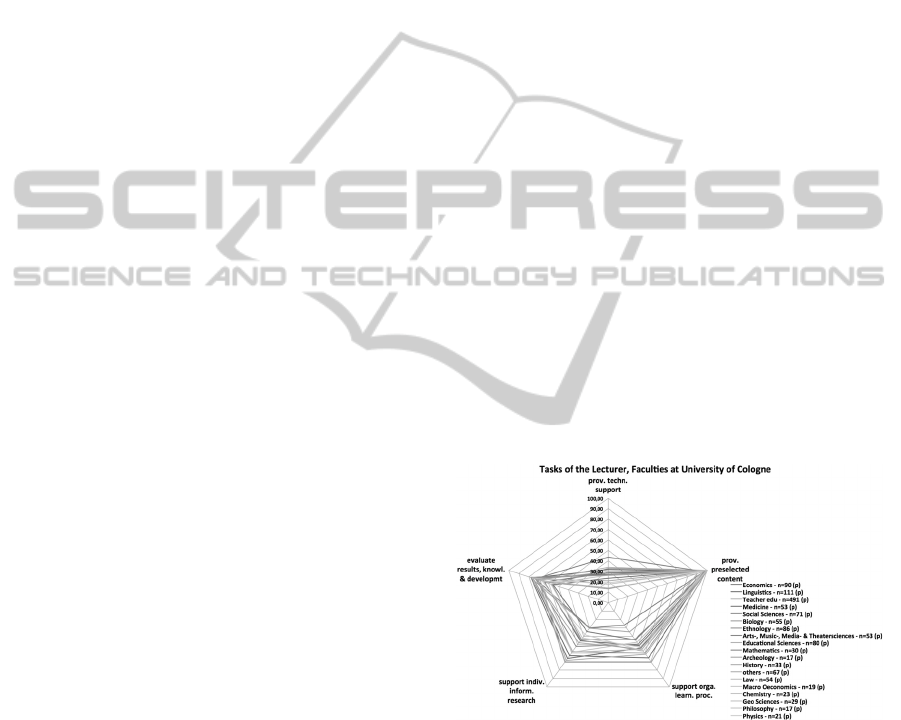

the data on faculty level. In Figure 1, we exemplarily

display the results of the University of Cologne re-

garding the thematic block “Tasks of the Lecturer”.

Figure 1: “Tasks of the Lecturer”, Faculties (Cologne).

On faculty level, we found deviations in the an-

swers of the students regarding all thematic blocks

and between each of the faculties within all three

universities. The general characteristics of the found

patterns were similar across faculties and items. The

displayed thematic block “Tasks of the Lecturer”

was the one with the highest level of diversity. Re-

garding this thematic block, the expectations of the

students generally were higher in faculties with low

numbers of students than in larger faculties.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

376

3.2 Educational Culture in Universities

For the comparison of the educational cultures on

university levels, we calculated the positive percent-

age values over the whole datasets (not about the av-

erages of the faculties) from each of the German

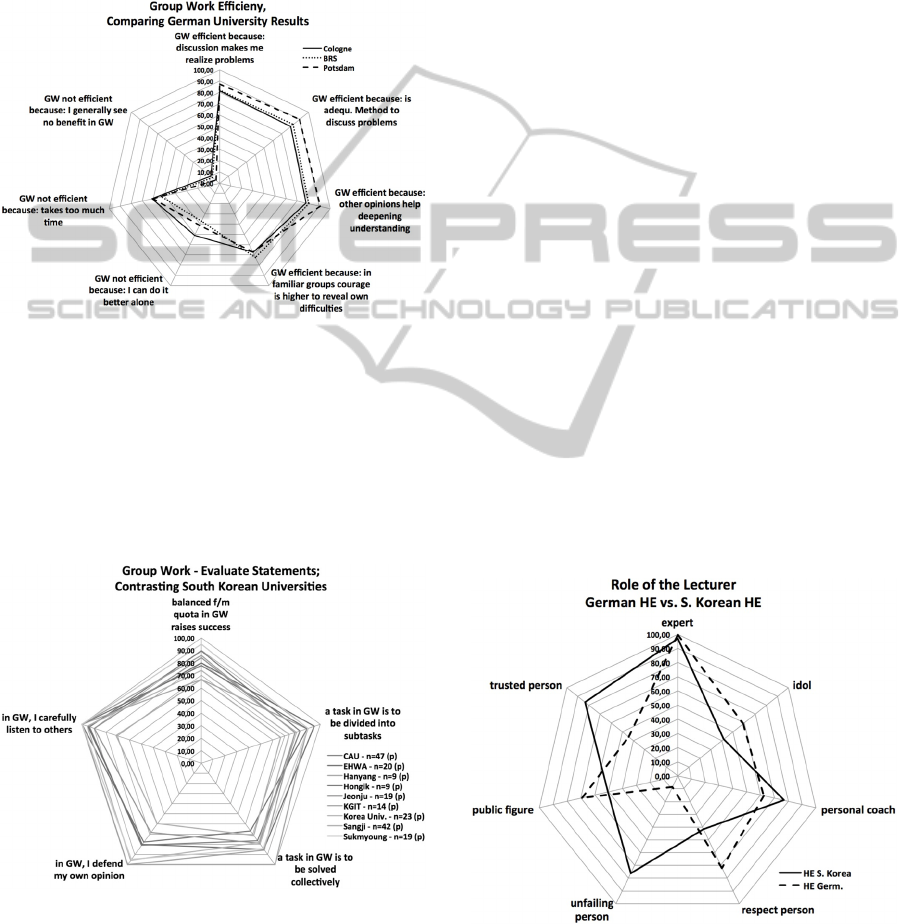

universities. Figure 2 displays the results regarding

the thematic block “Group work efficiency”.

Figure 2: “Group Work Efficiency”, German Universities.

After having built the averages of each universi-

ty, patterns resulted, which were very similar to each

other. We yet had to find out, if the data of the South

Korean sample would lead to a similar effect. Figure

3 displays the results from the thematic block

“Group Work – Evaluate Statements”, considering

only the South Korean universities, where at least

nine sample elements were available.

Figure 3: “Group Work - Evaluate Statements”, South Ko-

rean Universities.

Also here, we can find quite similar patterns

when comparing the results of the South Korean

universities. In the South Korean sample, we found

extreme outliers regarding some thematic blocks,

mainly from universities with very small numbers of

sample elements and particularly from the KGIT,

which just provides extra occupational programs.

3.3 Educational Culture:

National Level

In order to evidently conclude that our findings ac-

tually had something to do with culture on a national

level and not just with university traditions, which,

by coincidence, were found to be similar, we needed

to find clear differences between the averages of the

German and the South Korean universities. We did

not expect to find such differences regarding all

thematic blocks but surely regarding the thematic

blocks “Tasks of the Lecturer” and “Role of the Lec-

turer”. South Korean universities, by law, must em-

ploy one professor per each 10 registered students.

In Germany, no such regulation is defined which of-

ten results in very crowded classes and rather anon-

ymous students who do not expect any services from

their professors apart of being responsible for a lec-

ture and providing evaluations. Thus, the expecta-

tions, which South Korean students assign to their

lecturers, are far higher, and the student-lecturer re-

lationship, is much closer. Further on, South Korean

students would never question their lecturers but in-

stead expect them to always provide the best possi-

ble solution for a specific problem. German students,

in contrast, explicitly learn from the very beginning

to put everything into question. Figure 4 displays

both national university averages regarding the the-

matic block “Role of the Lecturer”.

Figure 4: “The role of the Lecturer”, Comparing results

from German and South Korean Universities.

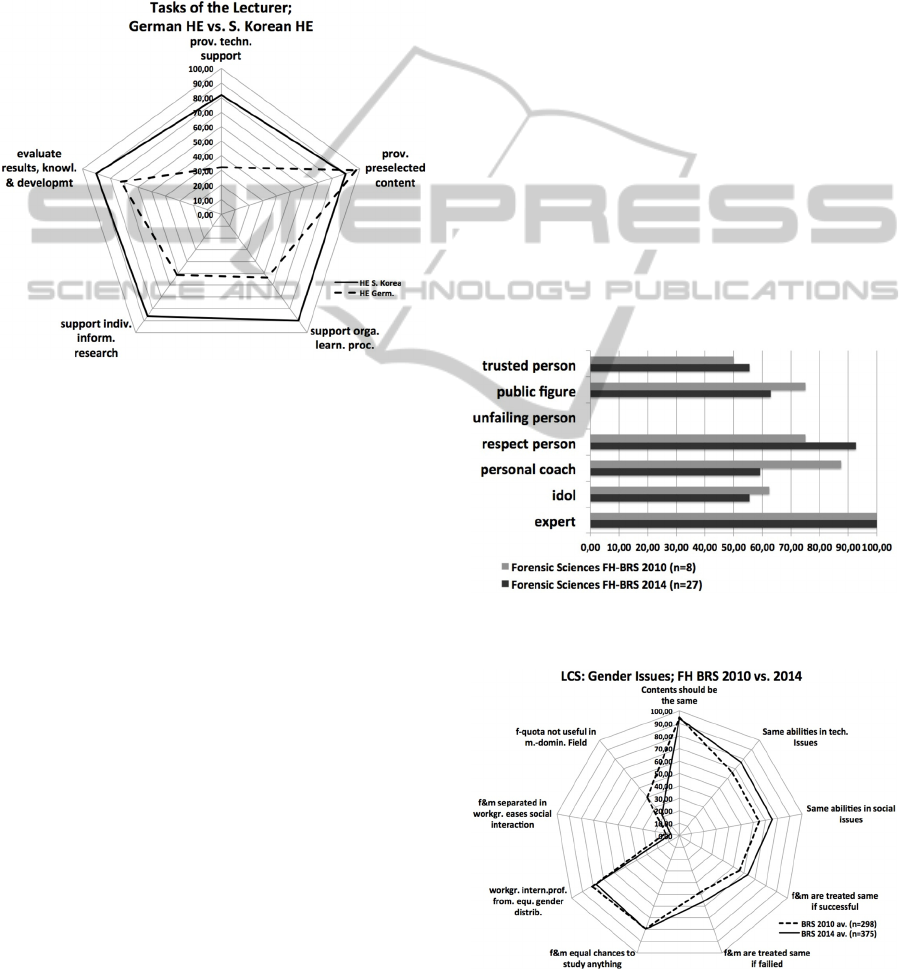

Figure 5 displays the average of both national da-

tasets regarding the thematic block “Tasks of the

TheWholeIsMorethantheSumofItsParts-OnCultureinEducationandEducationalCulture

377

Lecturer”. As expected, regarding the items “tech-

nical support”, “support for the individual literature

research”, and “support for the organization of the

individual learning process”, the expectations of the

students were very different between both national

contexts. While the responses of the German stu-

dents were indifferent towards all three items (re-

sults between 40 and 60%), the Korean students did

very clearly demand related services.

Figure 5: “Tasks of the Lecturer”, Comparing results from

German and South Korean Universities.

The results of both national contexts fully con-

firmed what we expected to find from our experi-

ences. Regarding other thematic blocks, prior known

differences also were mostly reflected. Where we

actually found amazing results in the South Korean

context was regarding the thematic block “Feed-

back”. While we had expected that criticism general-

ly would be a difficult matter for the South Korean

students because of the Asian concept of shame, the

students eventually claimed the contrary, which was,

perceiving (constructive) critique towards their work

results and study progress as motivating, and even

feeling confused in the lack of critical feedback.

3.4 Findings Regarding Educational

Culture in Professional Training

We evaluated the results of the two enterprises that

provided seven and 14 sample elements. We found

significant differences between the learning cultures

of each of the groups of employees, which were in

line with the basically different organizational cul-

tures of the enterprises. The results additionally dif-

fered a lot from the results from the German univer-

sities. For example, instructors in professional train-

ing were not seen as respect persons but just as ex-

perts in their field and were expected to provide far

more support than the lecturers in the universities.

This fully reflects their particular role in the context

of professional training. In the context of profes-

sional training, group work generally was seen as

difficult, and learning tasks were reported to rarely

being completed in time (Richter and Adelsberger,

2012).

3.5 Persistence of Learning Culture

From our repetitive study, which took place in the

Winter 2014/15 at the University of Applied Scienc-

es BRS, we learned that Learning Culture appears to

slightly change in accordance with changes of edu-

cational practices on faculty level, while the average

university results kept almost the same. For exam-

ple, in 2010, the department of Forensic Sciences

had recently started with just a very small number of

students. In that time, we found the students perceiv-

ing their lecturers much more as coaches than in

2014, when the number of students studying Foren-

sic Sciences was much higher (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Changes in Learning Culture between 2010 and

2014; Forensic Sciences: “Role of the Lecturer”.

Figure 7: Persistence of Educational Culture: FH BRS

2010 vs. 2014; Thematic block “Gender Issues”.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

378

Almost no deviations larger than 10% were found

between the average results from both studies on

university level. Figure 7 shows the thematic block

“Gender Issues” with the highest found level of de-

viation.

The found changes fully reflected the German “Zeit-

geist”: Currently, an intensive public discussion

started regarding the legal enforcement of a female

quota for Top-Management positions.

3.6 Limitations

Besides the fact that educational culture varies be-

tween academic and professional education and thus,

the results of the LCS are not transferable across ed-

ucational contexts, we found significant deviations

between our test studies from British and French

Cameroon. We conducted an a-prori analysis and

from 55 sample elements, a single one from French

Cameroon was wrongly assigned to the characteris-

tics of the sample from British Cameroon. This

means that we generally cannot assume that Learn-

ing Culture is homogenous within a country. Exam-

ples showing homogenous educational cultures must

rather be understood as exceptional cases.

4 DETERMINING CONFLICTS

IN EDUCATION

Being able to recognize cultural differences regard-

ing selected issues across educational contexts is not

yet sufficient for understanding or even determining

at which level a particular cultural distance could

eventually lead to a conflict situation and maybe be-

come a threat for the motivation of learners. Cultural

distance has been a subject of discussion since some

decades. A clear definition of the term does not exist

but it originally was used in the context of etic cul-

ture research, in which the cultures of whole socie-

ties were quantified and compared according to a

small number of key values (such as provided by the

dimensions model of Hofstede et al., 2010). Shenkar

(2001) criticised the general concept of cultural dis-

tance as creating the illusion of an easy way to

measure something, as complex as culture that actu-

ally is not fully comprehensible at all. In this con-

text, Chen (2010) and Hatakka (2009) argued if

quantifying cultural barriers and in the wider sense

also culture-related conflicts would make sense on

this level at all, because they can be highly context-

related: Not the measurable culture-related aspects

alone are responsible for barriers, but the whole set

of characteristics within a situation, including ones’

individual ability to deal with unexpected situations.

In the field of Technology Enhanced Learning, Pirk-

kalainen et al. (2014) revived the term “cultural dis-

tance” with the meaning to determining individual

reasons for selected culture-specific barriers against

the production, usage, and/or repurposing of Open

Educational Resources.

In our research, we needed to find causative

characteristics because, even though, being unable to

eliminate all potential reasons for conflicts, we can

avoid going beyond the pain thresholds of the learn-

ers. Pain thresholds on individual level depend on

whole situations and current moods, but on the larg-

er scale, the crossing surely also is triggered by spe-

cific characteristics or events that generally are con-

sidered as “must-be” or “no-go”; eliminating such

triggering characteristics would be a good start to-

wards culture-sensitive education.

The whole discussion on how to quantify cultur-

ally relevant aspects through key-values for whatev-

er purpose appeared like circling around and did not

lead us to a solution in terms of finding measures for

conflict detection and prevention. What if the con-

cept of quantification itself simply isn’t adequate for

our purpose? Pless and Maak (2004) suggested gen-

erally not to understand culture as static set of varia-

bles, but as a measure to which extent people within

a society tend to accept deviations from what they

would consider to be appropriate. This understand-

ing of culture appeared promising for our purposes.

Until some years ago, in Germany, the “Central

Office for the Allocation of Places in High Educa-

tion” (“Zentralstelle für die Vergabe von

Studienplätzen”) assigned students who wanted to

study in a specific field to more or less random uni-

versities. This means that generally it was assumed

that qualified enough German school leavers were

capable to study in whichever university, independ-

ent of the institutional culture and local practices.

Adopting the idea of Pless and Maak and combining

it with the results from the LCS, this would mean

that all characteristics provided by German universi-

ties would define something like a minimum area of

acceptance, and in its’ extremes, define the pain

threshold. To which extent students can cope with

more extreme situations, might differ individually.

We did not have a chance to investigate the

German universities, which we considered having

most extreme characteristics according to guidance

and strictness – on the one side, the two German

military universities with their trimesters and on the

other, anthroposophical universities with a very low

amount of formal examinations. Our samples, how-

TheWholeIsMorethantheSumofItsParts-OnCultureinEducationandEducationalCulture

379

ever, included some faculties with extreme charac-

teristics. We assumed these could alternatively be

used to define the margins of the acceptance level.

The investigated South Korean universities, in con-

trast, included extreme cases, from very small uni-

versities to large ones and even a university with ex-

clusively extra occupational programs for adults. We

again created net diagrams contrasting both contexts

but this time, not according to the individual charac-

teristics or average values, but the whole spectrum

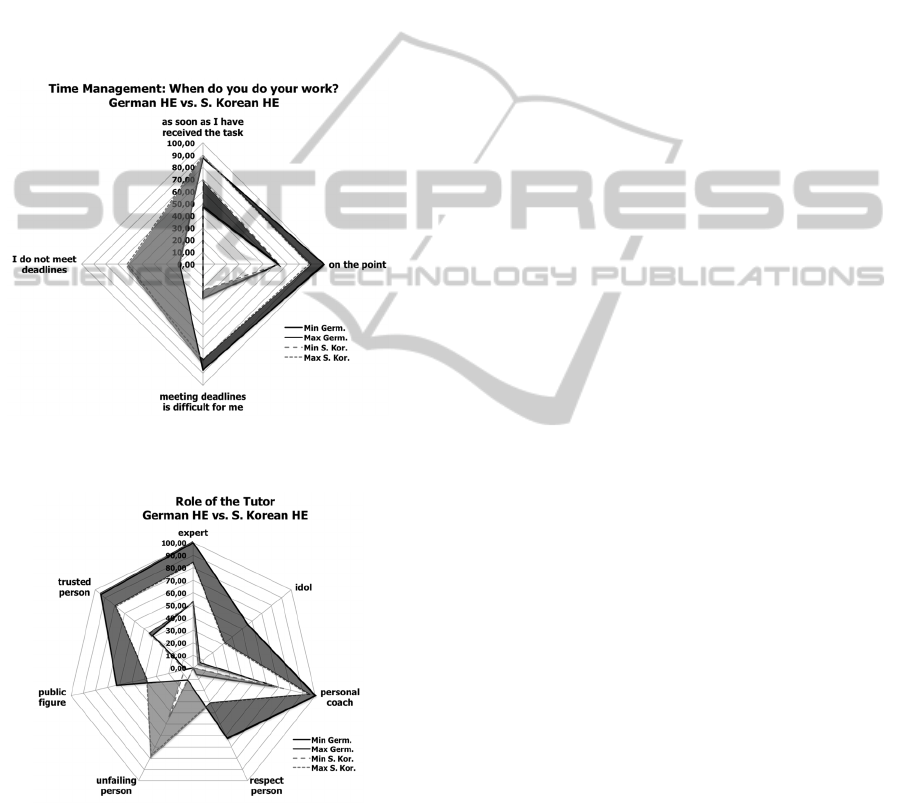

between found extreme values. The Figures 8 and 9

show the results according to the thematic blocks

“Time Management” and “Role of the Tutor”.

Figure 8: Thematic block “Time Management”; Con-

trasting Areas of Acceptance to define Cultural Distances.

Figure 9: Thematic block “Role of the Tutor”; Contrasting

Areas of Acceptance to define Cultural Distances.

For better recognition, we filled the parts of the

“acceptance areas” from each context if outside the

defined area of the other one, dark for the German

context (not within the answer spectrum of the South

Korean students) and grey for the South Korean.

Figure 8 (on the left side) shows that not meeting

deadlines appears to be more accepted in the South

Korean context than in the German context. In fact,

in South Korean universities, students often get a

second chance when they have reasonable excuses

why they missed a deadline. Work results of the

German students usually will not be accepted any-

more after the deadline has expired.

In Figure 9, the spectra from the thematic block

“Role of the Tutor” are contrasted: On the first sight,

the result we found in the South Korean context was

very surprising for us: The responses of the South

Korean students were very similar regarding both of

role of the lecturer and the role of the tutor. We par-

ticularly could not imagine that tutors (who in our

experience are older students) could be considered to

be unfailing. In later informal interviews with col-

leagues in Seoul, we found out that even though tu-

torials take place in a far more familiar environment

than lectures, mostly, the professors themselves hold

the tutorials. We do not know if the answers of

learners in pure online environments would be the

same in this (for us) very particular situation. Further

(qualitative) investigations in the South Korean con-

text are scheduled for 2016. This experience particu-

larly showed us that involving native people is es-

sential for the interpretation phase.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Culture often is promoted as something that easily

can be reduced to a small number of dimensions and

basic values. As such, it is understood as a set of

characteristics that apply to all people within nations

in the same measure without regard of their particu-

lar life situations. Our research on educational cul-

ture of the past years revealed fundamental re-

strictions against such a generalization and transfer-

ability of results across educational contexts (school

education, higher education, professional training).

Against common practice, we additionally found

that age and language influenced the culture-related

perceptions of our investigated learners.

After we found that this commonly promoted

concept of culture does at least not apply to the con-

text of education (Richter and Adelsberger, 2012),

we had to reconstruct our understanding of culture

before starting further investigations. Our currently

completed longitudinal study in the context of the

Learning Culture Survey provided the last missing

evidence that educational culture is persistent

enough on university level so that initializing an in-

ternational collection of related data on a large scale

actually makes sense. Further on, our quantitative

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

380

results from the LCS questionnaire revealed appro-

priate to recognize, measure, and understand cultural

differences in the context of education.

While we currently collect our data just in the

context of traditional (face-to-face) education, we

assume that the results are fully transferable to TEL;

at least for learners and educators who are used to

traditional forms of education and newly enter such

a scenario. An extension of our studies to education-

al programs that exclusively offer online access is

planned for the next years.

The datasets from the LCS enable learners and

educators who are going to study and/or teach in

other cultural contexts (online or offline) to start

their efforts with a better understanding of the ex-

pectable peculiarities. In terms of conflict preven-

tion, learners can adjust their initial expectations and

find out about commonly accepted behavior in the

targeted context (e. g., higher education in a specific

country. Educators get an impression of the reasons

for particular attitudes of their future learners and

can develop a better understanding of their needs in

terms of adopting their own accustomed teaching

design (and practices) to the new conditions.

The data can also be used in the retrospective, in

order to find the origins of repeatedly occurring cul-

ture-related conflicts in distinguished educational

settings (possibly even resulting in higher dropout

rates): On the basis of the issues considered in the

LCS, monitored events and situations can systemati-

cally be analysed for possible reasons (see e. g.,

Richter and Adelsberger 2014), improvement poten-

tial can be determined, and the next generation of

learning design can be defined accordingly.

As for the forecasting of possible educational

conflicts, the approach to define cultural distance

and related conflict potential on the basis of the level

of acceptance is demanding but the results appear

promising. However, even if one day, we will be

able to determine conflict potential in specific edu-

cational settings, we will never be able to generally

prevent all possible culture-related conflicts in edu-

cation. We have too little understanding of addition-

al influences and particularly, cross effects between

different influence factors. Anyways, for specific

situations and constellations, we eventually are/will

be able to estimate where culture-related conflicts

are likely to emerge. Further research is required on

this issue and planned for the next years.

The results of our longitudinal study indicate

that, on faculty level, the LCS reflects the students’

reaction on changes in their own learning environ-

ments. We have the intention to investigate to which

extent this finding could reveal helpful in the context

of impact management and quality management.

6 NEXT STEPS AND CALL FOR

CONTRIBUTION

With our questionnaire our and hitherto achieved

understanding of educational culture, we are able to

conduct standardized investigations regarding par-

ticular issues in different national and educational

contexts and compare found results across contexts.

We yet lack the understanding to explain (in detail)

the reasons for found results. For this purpose, addi-

tional qualitative investigations need be implement-

ed as follow-ups. We are currently developing

standardized methods that enable us not only to

pointedly investigate reasons for certain cultural

perceptions and attitudes of learners but which addi-

tionally are similar enough to lead to results that

eventually are comparable across contexts.

We are constantly extending our database and

looking for opportunities to conduct the LCS in fur-

ther educational contexts. Our long-term aim is to

develop and provide an open database on education-

al culture. This database shall support both educators

and learners all over the world to better understand

other contexts’ educational cultures. Such an under-

standing is essential, particularly when having to

cope with the demands of culture-sensible education

in international classrooms or with too highly or

wrongly set expectations.

However, for that purpose we need a lot more re-

liable data from all over the world. Hence, we would

like to invite other researchers and educational insti-

tutions to take part and contribute to the Learning

Culture Survey.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Even though we did not yet apply for or receive pub-

lic or private funding for this research, we would

like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions and

support we received from our team, friends, col-

leagues, students, institutions, organizations, transla-

tors, and many others.

REFERENCES

Baur, N., 2008. Das Ordinalskalenproblem. In N. Baur and

S. Fromm (Eds.), Datenanalyse mit SPSS für

Fortgeschrittene. 2

nd

Ed., Wiesbaden: VS Verlag, 279-

289.

Bowman, R.F., 2007. How can students be motivated: A

misplaced question? Clearing House, 81(2), 81-86.

TheWholeIsMorethantheSumofItsParts-OnCultureinEducationandEducationalCulture

381

Buehler, E., Alayed. F., Komlodi, A., and Epstein, S.,

2012. „It Is Magic“: A global perspective on what

technology means to youth. In: Proceedings of the

CATaC'12 conference, 100-104.

Chen, Q., 2010. Use of Open Educational Resources:

Challenges and Strategies. Hybrid Learning, 339-351.

Douglas, I., and Liu, Z., 2011. Global Usability. London:

Springer.

Garland, R., 1991. The Mid-Point on a Likert-Scale: Is it

Desirable? Marketing Bulletin, 2/1991, Research Note

3, 66-70.

Haberman, M., 1995. Star teachers of children in poverty.

Kappa Delta Pi, West Lafayette.

Hatakka, M., 2009. Build it and they will come? Inhibiting

factors for reuse of open content in developing coun-

tries. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems

in Developing Countries, 37, 1-16.

Hoffmann, S., 2010. Schulabbrecher in Deutschland –

Eine bildungsstatistische Analyse mit aggregierten

und Individualdaten. Diskussionspapiere, No. 71,

Erlangen-Nürnberg: Friedrich-Alexander Universität.

Hofstede, G., 1980. Culture's Consequences – Internation-

al Differences in Work Related Values. London: New-

bury Park (herein used the 2

nd

edition from 2001,

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage).

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., and Minkov, M., 2010. Cul-

tures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. 3

rd

Ed., USA: McGraw-Hill Publishers.

Jones, M.L., 2007. Hofstede – Culturally questionable? In:

Proceedings of the 2007 Oxford Business and Eco-

nomics Conference, Oxford: Oxford University.

http://www.gcbe.us/2007_OBEC/data/confcd.htm.

Knapp, T.R., 1989. Treating Ordinal Scales as Interval

Scales: An Attempt To Solve The Controversy. Nursing

Research, 39(2), 121-123.

Köppel, P., 2002. Kulturerfassungsansätze und ihre

Integration in interkulturelle Trainings. Trierer

Beiträge zur gegenwartsbezogenen Ethnologie. Trier:

Fokus Kultur.

Kromrey, H., 2006. Empirische Sozialforschung. 11

th

Ed.,

Stuttgart: Lucius and Lucius.

Leidner, D., and Kayworth, T., 2006. A Review of Culture

in Information Systems Research: Toward a Theory of

Information Technology Culture Conflict. Manage-

ment Information Systems Quarterly, 30(2), 357-399.

Mitra, S., Dangwal, R., Chatterjee, S., Jha, S., Bisht, R.S.,

and Kapur, P., 2005. Acquisition of computing literacy

on shared public computers: Children and the “hole in

the wall”. Australasian Journal of Educational Tech-

nology, Nr. 21, 407-426.

Müller, H.-P., Kock Marti, C., Seiler Schiedt, E., and Arp-

agaus, B. (2000). Atlas vorkolonialer Gesellschaften.

Reimer, Berlin, Germany.

Nilsen, H., 2006. Action research in progress: Student sat-

isfaction, motivation and drop out among bachelor

students in IT and information systems program at

Agder University College, Nokobit. Tapir Akademisk

Forlag, Nokobit.

Oetting, E.R. 1993. Orthogonal Cultural Identification:

Theoretical Links Between Cultural Identification and

Substance Use. In M. R. de la Rosa, and J.-L. R. An-

drados, (Eds.), Drug Abuse Among Minority Youth:

Methodological Issues and Recent Research Advances,

Rockville, MD: National Inst. on Drug Abuse

(DHHS/PHS), 32-56.

Pirkkalainen, H., Jokinen, J., Pawlowski, J.M., and Rich-

ter, T., 2014. Overcoming the cultural distance in so-

cial OER environments. In: Proceedings of the

CSEDU 2014, SCITEPRESS, Portugal, 15-24.

Pless, N.M. and Maak, T., 2004. Building an Inclusive Di-

versity Culture: Principles, Processes and Practice.

Journal of Business Ethics, 54(2), 129-147.

Porst, R., 2008. Fragebogen: Ein Arbeitsbuch:

Studienskripten zur Soziologie. 1

st

Ed., VS Verlag für

Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden: GWV Fachverlage.

Richter, T., 2011. Adaptability as a Special Demand on

Open Educational Resources: The Cultural Context of

e-Learning. European Journal of Open, Distance and

E-Learning (EURODL), 2/2011.

Richter, T. and Adelsberger, H.H., 2011. E-Learning: Ed-

ucation for Everyone? Special Requirements on

Learners in Internet-based Learning Environments. In:

Proceedings of the EdMedia 2011, Chesapeake, VA:

AACE, 1598-1604.

Richter, T. and Adelsberger, H.H., 2012. On the myth of a

general national culture: Making specific cultural

characteristics of learners in different educational con-

texts in Germany visible. In: Proceedings of the CAT-

aC'12 conference, 105-120.

Richter, T., 2014. The Learning Culture Survey: An inter-

national research project on cultural learning attitudes.

English language questionnaire version for recogni-

tion. Due-Publico, Essen. Accessible at DOI:

10.13140/2.1.2877.5206.

Richter, T. and Adelsberger, H.H. 2014. Cultural Country

Profiles and their Applicability for Conflict Prevention

and Intervention in Higher Education. In: Stracke,

C.M., Ehlers, U.-D., Creelman, A., and Shamarina-

Heidenreich, T. (Eds.), Proceedings of the European

Conference LINQ and EIF 2014, Logos Verlag Berlin

GmbH, Berlin, 58-66.

Rothkrantz, L., Dactu, D., Chriacescu, I., and Chitu, A.G.,

2009. Assessment of the emotional states of students

during e-Learning. In: Proceedings of the Int. Confer-

ence on e-Learning and Knowledge Society, 77-82.

Sandanayake, T.C. and Madurapperuma, A.P., 2011. Nov-

el Approach for Online Learning Through Affect

Recognition. In: Proceedings of 5th International Con-

ference on Distance Learning and Education, Singa-

pore: IACSIT Press, 72-77.

Schenker, O., 2001. Cultural Distance Revisited: Towards

a Rigorous Conceptualization and Measurement of

Cultural Differences. Journal of International Business

Studies, 32(3), 519-535.

Smith, P.B., 2006. When elephants fight, the grass gets

trampled: the GLOBE and Hofstede projects. Journal

of International Business Studies, 37(6), 915-921.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

382