A Mobile Guardian Angel Supporting Urban Mobility for People

with Dementia

An Errorless Learning based Approach

Laura Freina and Ilaria

Caponetto

CNR-ITD, via de Marini 6, 16149, Genova, Italy

Keywords: Mild Dementia, Cloud Computing, Geolocation Systems, Errorless Learning.

Abstract: Dementia is one of the main causes of dependency for old people in the world, and, according to several

studies, the number of people affected by such a problem is bound to grow significantly in future. This

represents a high social cost. Memory loss and disorientation to space and time are among the most

common problems in the early stages of dementia, causing worry in caregivers and consequently social

isolation for the people involved. A mobile system in support of the autonomous mobility around town

would offer a double advantage: allowing for more independence of the dementia affected people and

reassuring caregivers. In this paper, we discuss the possibility of adapting an existing mobile system,

developed for intellectually impaired young adults, to these specific target users. We identify in the errorless

learning approach a possible method to support the learning of a new, technologically based system

accessible to people with mild dementia, highlighting some potential issues that still need further

investigation, in particular learning transfer and spontaneous use.

1 INTRODUCTION

According to several studies, the number of people

in the world that have some sort of dementia is very

large and will probably increase in the next years.

Among the early symptom of dementia, the most

frequently reported ones are loss of memory and

disorientation to space and time. Therefore, people

who have dementia in its early stages start having

difficulty in finding their way, they wander with no

apparent destination, they feel lost and sometimes

actually lose their way.

Wandering and getting lost is one of the main

concerns of families and caregivers. They have a lot

of pressure and responsibilities, and often end up

limiting the person’s access to outdoors. Moreover,

people with dementia themselves are aware of the

issue and often feel insecure with the fact that they

may not know where they are and what time of the

day it is, therefore they limit themselves or accept

the imposed limitations. Locked doors cause social

exclusion and reduce the person’s interests and

activities, also causing the illness to get worse in a

shorter time.

Having a system in support of the personal

independence of people with mild dementia, by

allowing and aiding their free movements around

town would give them more freedom and the

possibility to lead a more active life for a longer

time. At the same time, such a system would offer

families and caregivers a tool to keep in touch with

their cared ones and always know where they are.

People with dementia would find a support to tell

them the time, guide them home, offer the

possibility to get in touch with a friendly voice and

ask for help when needed with a simple press of a

button.

In this paper, after introducing the most common

problems that characterize the early stages of

dementia, we discuss how a platform supporting

urban mobility could be adapted to maintain, as long

as possible, the mobility of these new target users.

Issues related to learning and being able to use the

new technology from people with mild dementia are

discussed, along with a feasible methodological

approach to address them.

2 SETTING THE SCENE

Dementia is not a specific disease, but rather an

overall term that describes a wide range of

307

Freina L. and Caponetto I..

A Mobile Guardian Angel Supporting Urban Mobility for People with Dementia - An Errorless Learning based Approach.

DOI: 10.5220/0005502503070312

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (SocialICT-2015),

pages 307-312

ISBN: 978-989-758-102-1

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

symptoms associated with a decline in memory,

thinking and social abilities. In order to be classified

as dementia, the decline has to be severe enough to

reduce a person's ability to perform everyday

activities (Committee for Medicinal Products for

Human Use, 2008).

Although dementia mainly affects older people,

it is not a normal part of ageing, but rather the

consequence of some disease of the brain that

influences its functionalities. Alzheimer's disease

accounts for 60 to 70 percent of cases, vascular

dementia, which occurs after a stroke, is the second

most common dementia type, together they account

for about 90% of the cases.

Dementia is one of the major causes of disability

and dependency among older people worldwide:

according to the World Health Organization (WHO)

(World Health Organization, 2012), in 2012 35.6

million people had dementia. The total number of

people with dementia was projected to almost

double every 20 years, which means 65.7 million in

2030 and 115.4 million in 2050. About 150.000 new

cases per year have been estimated in Italy only (Di

Carlo et al., 2002).

Dementia has significant social and economic

implications in terms of direct medical and social

costs as well as the costs of informal care. The WHO

estimated that in 2010, the total global societal costs

of dementia was around 1.0% of the worldwide

gross domestic product or 0.6% if only direct costs

are considered.

Furthermore, dementia is devastating for the

families of affected people and for their caregivers.

Physical, emotional and economic pressures can

cause great stress to families and caregivers, and

support is required from the health, social, financial

and legal systems.

Within this frame, loss of memory and

orientation to space and time is a key issue in the

early stages of dementia. When the illness is still in

its mild or moderate stages, the person with

dementia would still be capable of moving around

town and leading an active life. Nevertheless, people

with dementia report difficulties in living with the

insecurity that you do not know where you are and

what time it of the day it is (Harris, 2006).

Unfortunately, the person’s freedom is often

drastically reduced, when not completely stopped,

by caregivers, who do not feel at ease when letting

their assisted ones free to move alone. People with

dementia are frequently denied the basic rights and

freedoms available to others, the limited or restricted

access to outdoors also causes them to be socially

isolated. These issues could be alleviated with the

use of technology (Topo, 2008), which can be

helpful in providing specific support and therefore

allowing more freedom for the person with dementia

to move around town in an autonomous manner.

Giving people with mild dementia a system that

can offer them a guide and help, which is always

present but not invasive, means giving them the

chance of being socially active for a longer time,

keeping up their interests and, therefore, slowing

down the progression of the illness. Furthermore, the

system would increase safety of the person and offer

support and reassurance to caregivers.

3 TOWARDS INNOVATIVE AIDS

In a previously developed project, “Smart Angel”, a

cloud based mobile system has been developed with

the aim of supporting urban mobility of people with

intellectual disabilities, in particular young adults

with the Down syndrome. Our position is that the

system, after being specifically adapted to the

different target population, could be effective also in

supporting and enhancing the orientation abilities of

people with mild dementia.

3.1 The Smart Angel Project

Smart Angel (Smart Angel, 2014), an Italian

regional project co-funded by the Liguria Region,

aims at favouring social inclusion of people with

intellectual disabilities by offering them accessible

tools supporting their daily activities and urban

mobility. The name “Smart Angel” wants to recall a

guardian angel, always at the person’s side,

providing help when needed in a non-invasive

manner.

Supporting the urban mobility of intellectually

impaired people is a key issue to promote and

enhance their full autonomy. Thus, one of the main

aims of the Smart Angel project was to enable them

to move around in the urban context and reach

relevant places (workplace, leisure, sports, home) by

themselves. This was done by relying on last-

generation existing technologies.

The project has been organized in a first training

phase in which the users’ orientation and mobility

skills are stimulated and trained by means of ad hoc

developed Serious Games, which make use of

innovative virtual reality devices (Freina, Busi,

Canessa, Caponetto, and Ott, 2014) (Freina and Ott,

2014). After this phase, the users start to move

around in their town and to get confident with places

and public transports. At the beginning, they are

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

308

closely supported and monitored by their educators.

As the user’s skills grow, the links with the

educators get looser until they are allowed to move

around in complete autonomy (at least along the

established paths) by relying only on the help of

mobile devices. Actually, this phase makes in-depth

use of both cloud and mobile technologies (Costa,

Freina, and Ott, 2015).

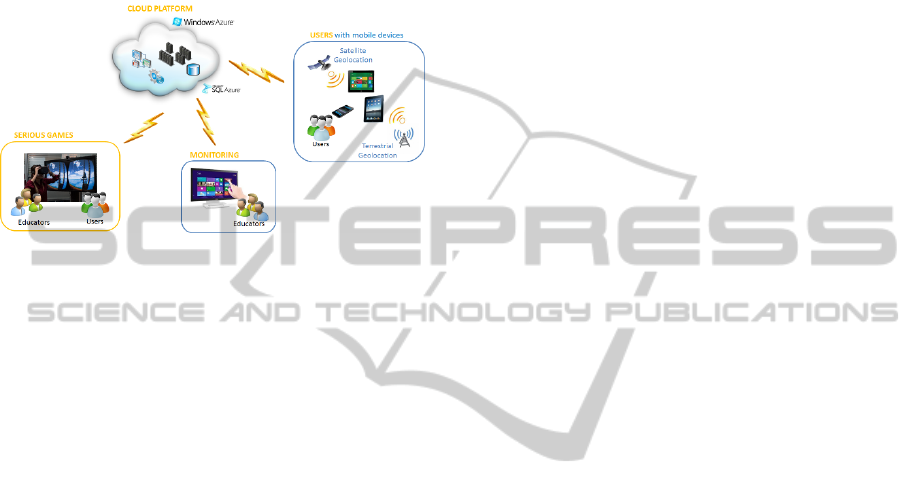

Figure 1: The Smart Angel System.

A central cloud based platform collects all the

users’ data and connects the other elements of the

system. Each user has his own smartphone, equipped

with specific apps, which allows him both to get

appropriate support during daily standard activities

and to move safely around town. A combination of

satellite and ground localization systems is involved

in tracing the users’ movement.

3.2 Adaptation of Smart Angel to the

New Target Population

The Smart Angel system has been developed for a

target population of intellectually impaired young

adults who have the abilities, either potential or real,

to move in town autonomously. Therefore, attention

has been focused on the development of basic

abilities and specific support to mobility. The typical

Smart Angel user is born in the digital era and is

acquainted with technology; they usually have their

own Smart Phone, which they used before entering

the project and learning a new app is considered a

fun activity.

People with dementia, on the other hand, are

usually aged and often have very little know-how

with respect to the new technologies. Furthermore,

they do not need to learn new abilities for moving

around, but rather to maintain already known skills

as long as possible. The basic functionalities needed

to support free mobility are the same, but the user

interfaces, as well as the initial intervention needed

to get the user acquainted with the new technologies

differ deeply.

It has been demonstrated that old people with

mild dementia symptoms can benefit from the use of

user-friendly technologies, even though they need

ongoing education and support (Hanson et al.,

2007).

4 AN INSIGHT INTO A POSSIBLE

METHODOLOGY

As reported in literature, the use of technologies,

both new and known ones, is possible for people

with dementia in its mild stages (Robinson, Brittain,

Lindsay, Jackson, and Olivier, 2009).

Robinson et al. report the development of a

technological system to support the independence of

people with dementia. Interestingly, the final users

have been closely involved in the definition of the

system to be tested, and the key issues to be

addressed were related to concerns about getting

lost, loss of confidence, which caused to the

reduction of daily activities and caregivers’ anxiety.

The use of some tracking technology and the

constant possibility to get in touch with one another

was considered as a good opportunity for caregivers

to give virtual support and give the person with

dementia more freedom.

Personalized solutions have been developed to

address some important drawbacks: the size of the

devices (the commercial ones were either too heavy

and awkward to carry or too small and difficult to

handle) and the fact that people with dementia may

have weak vision, making the use of the commercial

devices even more difficult. Today, these issues can

be easily solved thanks to the new technologies,

which, on the one hand offer tools that are small and

light, while, on the other hand, thanks to special

interfaces, can easily overcome the limitations due

to sight impairments.

Robinson et al. focus also on the reported

concern about social stigmatization: people

participating in the project wanted a system to

guarantee them a two-way communication and guide

them home that had to be flexible and discreet. This

issue is now automatically solved since the use of

smart mobile phones, equipped with navigation

systems and vocal interfaces has become widely

spread. Nobody would regard as strange speaking on

the phone, using a GPS navigation system or

interrogating a smart phone while walking around

town.

The reported experiments focused well on user

requirements, design and prototyping, but did not

AMobileGuardianAngelSupportingUrbanMobilityforPeoplewithDementia-AnErrorlessLearningbasedApproach

309

investigate on the solutions being actually used and

being effective. It would be of great interest to

explore which could be a possible methodology to

teach the target population the use of the new

technological tools in such a way that these tools

would actually be used effectively in real life. It

appears that the errorless learning approach could be

the answer to this issue.

4.1 Errorless Learning

The concept of errorless learning has been

introduced by Terrace (Terrace, 1963) who used it to

train pigeons in discriminating red and green lights.

In the errorless approach, the aim is that of

significantly reducing the error rate. People learn by

performing the same operation repeatedly, just like

the trial and error approach, but in this case, specific

attention is put on minimizing the number of errors.

Learning through trial and error requires the

learner to recognize when and where the error

occurred in order to resolve it. The explicit memory

is responsible for the recognition and correction of

the errors; this requires good skills of analysis,

which may be compromised in people with

dementia. If the error is not recognized as such, it

could be encoded into memory, which would result

in wrong responses later or conflicts between the

correct and the erroneous information. The errorless

approach, based on avoiding errors as much as

possible, minimizes this problem (Clare et al., 2000).

Different methods can be employed to minimize

errors during the learning phases, depending also on

the type of skill that has to be learned. For non-

procedural knowledge, spaced retrieval (in which the

information is rehearsed repeatedly with increasing

intervals between rehearsals) and vanishing cues (in

which the amount of cues given is enough to be

successful and is then reduced, keeping it always at

the minimum number required for success) are the

most used techniques. A stepwise approach is

suggested for the procedural knowledge.

4.2 Errorless Learning and Dementia

According to de Werd (de Werd, Boelen, Olde

Rikkert, and Kessels, 2013), people with dementia

still have the ability to acquire meaningful skills. In

particular, he reports the errorless approach to

learning as being more effective than other

approaches in teaching adults with dementia. He

presents various works based on the errorless

approach, reporting positive and long lasting effects

in learning the use of technological devices from

people with dementia: gains are generally

maintained at follow-up. In most cases novel tasks

were learned, in other cases familiar but forgotten

tasks or information were relearned.

People with dementia usually need a continuous

support in order to maintain their existing skills:

reinforcement may be frequently needed. Therefore,

caregivers would have to be involved in the learning

process. Even if attention has to be paid in order not

to overload them with responsibilities, they are

fundamental to train and maintain the newly learned

skills in the home environment.

In our case, we affirm that an errorless approach

could be used to teach people with mild dementia

how to use these new tools in order to have the best

possible support in their movements around town.

Such training has to be specifically studied keeping

in mind the distinctive problems of the target

population involved in the project, personalizing

each training path to individual needs in order to

stimulate and maintain, as much as possible, all the

skills and knowledge that are still available to the

user.

Furthermore, Nygård and Starkhammar (Nygård

and Starkhammar, 2007) report that sometimes

technology offers people with dementia a feeling of

safety that actually proves to be false. For example,

they may feel safe because they are carrying a

mobile phone and they are aware that they have the

possibility to ask for help if needed, but they have

actually never used the phone and may not be able to

do so. In our case, this phenomenon will also be

analysed. Even if the person may not be able to use

the tool in a real emergency, the increase in his

personal confidence resulting from the availability

of the system may lead to a better quality of life.

Moreover, caregivers would have the possibility to

trace the person at any moment, relieving their level

of anxiety.

4.3 Issues for Further Investigation

Even though the errorless learning approach,

enriched with specific training sessions tailored to

individual needs seems to be a feasible way to get

the most out of our system, some main issues are

still open and require further investigation. In

particular, we can foresee three critical issues:

physical management of the smart phone, transfer of

the learned skills to new situations and spontaneous

use of the tools when actually needed.

As far as the management of the smart phone is

concerned, the users need to learn some procedural

knowledge: sequences of actions to be performed at

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

310

certain times to guarantee its usability. In particular,

they have to remember to charge the smart phone

and to take it with them when leaving the house,

after checking that it is switched on. This issue can

be addressed by specific and fixed routines: in the

sequence of actions, the previous one triggers the

following step. For example, every time that the user

enters the house, he has to put the phone in charge in

a visible place near the entrance. When leaving the

house, he has to take the phone, check that it is on,

and carry it with him.

Learning transfer refers to the ability to use past

experiences to do a new task or the same task in a

new context (Barnett and Ceci, 2002). As reported

by Bier et al. (Bier et al., 2008), sometimes in

dementia learning is very effective, but transfer of

the learned skills to a new situation which may be

different from the one in which the skill has been

learned can be difficult. There are several techniques

aimed at minimizing this problem. For example,

learning can happen in locations that are as similar

as possible to the contexts where the skills will then

have to be applied, i.e. the users can practice the use

of their new devices while actually walking in the

real roads of their town. Furthermore, specific tasks

can be designed to stimulate transfer by asking the

person to use the new skills in different, but similar,

contexts. Studies reported by Bier et al. show that

transfer is possible in mild dementia when the target

situation is similar enough to the learning one.

The last critical issue that we have identified is

related to spontaneous use of the learned new skills

in everyday living, which has not yet been

extensively studied in literature. As reported by Bier

et al. (Bier et al., 2008), it may happen that a new

skill is learned, but then the person does not

spontaneously use it in everyday life, even when

prompted to do so. In our case, in order to use the

newly learned tools, the user has to be able to

recognize the situation (i.e. he is having problems

with his orientation to space or time), remember the

information (remember that he has a tool that can be

helpful and how to use it) and have an intention to

do it. It appears that stressing situations influence

negatively the users’ performance, therefore, an

action that may not cause any problem in a normal

situation, may be impossible when the context

becomes stressful. According to Nygård and

Starkhammar, using a technological tool in case of

an emergency outside the home is stressful, and

therefore unlikely to happen (Nygård and

Starkhammar, 2007).

5 CONCLUSIONS

Dementia appears to be one of the major causes of

dependency for old people in the whole world.

Among the most common symptoms of dementia,

there is memory loss and weak orientation to space

and time, which impact on the individual freedom to

move autonomously around town, causing social

isolation and limiting the person’s interests and

activities. We propose to use a cloud-based system,

which has been developed in support of the urban

mobility of people with intellectual disabilities and

that can be adapted to people affected by mild to

medium dementia. The system, which uses a set of

specific apps on a smart phone and a combination of

geolocation systems to keep track of the user’s

movements, offers him the possibility to receive

help when needed, to get in touch with a friendly

voice or to have suggestions to find the way back

home. At the same time, the system would be

socially discrete and non-invasive, guaranteeing the

person’s privacy and independence. Furthermore,

while increasing both independence and safety of the

person, the system would also support and reassure

families and caregivers.

Several issues have to be considered to make this

goal feasible. First of all, a specific adaptation of the

tool has to be done in order to respond to the

different needs of the users, making interfaces as

simple as possible and straightforward to use

(Bocconi, Dini, Ferlino, and Ott, 2006). Special

attention has then to be paid to the introduction of

the system into the users’ lives. The errorless

learning approach is probably the best way to teach

people with mild dementia how to take care and use

their new device. Individual learning paths need to

be studied with the direct and continuous support of

the caregivers and specific fixed routines are needed

in order to guarantee that the users remember to

charge their smart phones and carry them when

leaving the house.

Some issues still need further investigation. The

training phase has to be integrated with specific

actions to foster learning transfer, helping the people

with dementia to recognize those situations when the

tools could be helpful even when they differ from

the learning ones. Furthermore, spontaneous use of

the new system still has to be investigated,

especially with respect to stressing situations as may

be emergencies or, simply, realizing that we have

lost our way home.

A specific experiment is needed in order to find

an answer to these research questions, which would

give the community further insight on the learning

AMobileGuardianAngelSupportingUrbanMobilityforPeoplewithDementia-AnErrorlessLearningbasedApproach

311

possibilities still available to people with mild

dementia, as well as an assessment on the real

advantages of the use of a simple mobile based

system in support of their mobility.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank Michela Ott and

Ilaria Caponetto for their patience in reading and

making useful comments the present paper.

REFERENCES

Barnett, S. M., and Ceci, S. J. (2002). When and where do

we apply what we learn?: A taxonomy for far transfer.

Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 612.

Bier, N., Provencher, V., Gagnon, L., Van der Linden, M.,

Adam, S., and Desrosiers, J. (2008). New learning in

dementia: transfer and spontaneous use of learning in

everyday life functioning. Two case studies.

Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 18(January 2015),

204–235. doi:10.1080/09602010701406581.

Bocconi, S., Dini, S., Ferlino, L., and Ott, M. (2006,

September 20). Accessibility of Educational

Multimedia: in search of specific standards.

International Journal of Emerging Technologies in

Learning (iJET). Retrieved from http://online-

journals.org/index.php/i-jet/article/view/60.

Clare, L., Wilson, B. A., Carter, G., Breen, K., Gosses, A.,

and Hodges, J. R. (2000). Intervening with Everyday

Memory Problems in Dementia of Alzheimer Type:

An Errorless Learning Approach. Journal of Clinical

and Experimental Neuropsychology, 22(1), 132–146.

doi:10.1076/1380-3395(200002)22.

Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use.

(2008). Guideline on medicinal products for the

treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease and other dementias

(No. CPMP/EWP/553/95 Rev. 1). London: European

Medicines Agency.

Costa, F., Freina, L., and Ott, M. (2015). A Cloud

Computing Based Instructional Scaffold to Help

People with the Down Syndrome Learn Their Way in

Town. In INTED (p. in press).

De Werd, M. M. E., Boelen, D., Olde Rikkert, M. G. M.,

and Kessels, R. P. C. (2013). Errorless learning of

everyday tasks in people with dementia. Clinical

Interventions in Aging, 8, 1177–1190.

doi:10.2147/CIA.S46809.

Di Carlo, A., Baldereschi, M., Amaducci, L., Lepore, V.,

Bracco, L., Maggi, S., … Inzitari, D. (2002). Incidence

of Dementia, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Vascular

Dementia in Italy. The ILSA Study. Journal of the

American Geriatrics Society, 50(1), 41–48.

doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50006.x.

Freina, L., Busi, M., Canessa, A., Caponetto, I., and Ott,

M. (2014). Learning to Cope With Street Dangers: an

Interactive Environment for Intellectually Impaired. In

EDULEARN14.

Freina, L., and Ott, M. (2014). Discussing Implementation

Choices for Serious Games Supporting Spatial and

Orientation Skills. In ICERI 2014 (pp. 5182–5191).

Hanson, E., Magnusson, L., Arvidsson, H., Claesson, A.,

Keady, J., and Nolan, M. (2007). Working together

with persons with early stage dementia and their

family members to design a user-friendly technology-

based support service. Dementia, 6(3), 411–434.

doi:10.1177/1471301207081572.

Harris, P. B. (2006). The Experience of Living Alone

With Early Stage Alzheimer’s Disease: What Are the

Person's Concerns? Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly, 7(2),

84–94.

Nygård, L., and Starkhammar, S. (2007). The use of

everyday technology by people with dementia living

alone: mapping out the difficulties. Aging and Mental

Health, 11(February 2015), 144–155.

doi:10.1080/13607860600844168.

Robinson, L., Brittain, K., Lindsay, S., Jackson, D., and

Olivier, P. (2009). Keeping In Touch Everyday

(KITE) project: developing assistive technologies with

people with dementia and their carers to promote

independence. International Psychogeriatrics / IPA,

21(3), 494–502. doi:10.1017/S1041610209008448.

Smart Angel. (2014). Project Description. Retrieved from

www.smartangel.it.

Terrace, H. S. (1963). Discrimination learning with and

without “errors”. Journal of the Experimental Analysis

of Behavior, 6, 1–27. doi:10.1901/jeab.1963.6-1.

Topo, P. (2008). Technology Studies to Meet the Needs of

People With Dementia and Their Caregivers: A

Literature Review. Journal of Applied Gerontology,

28(1), 5–37. doi:10.1177/0733464808324019.

World Health Organization. (2012). Dementia. Retrieved

from

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs362/en/

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

312