Social Networking Sites: An Exploration of the Effect of National

Cultural Dimensions on Country Adoption Rates

Rodney L. Stump

1

and Wen Gong

2

1

Towson University, Towson, MD, U.S.A.

2

Howard University, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

Keywords: Social Networking Sites, National Adoption Rates, Culture.

Abstract: This study investigates the impact of the several dimensions of Hofstede’s cultural framework on the

adoption rates of social networking sites (SNS) across 30 countries, while controlling for a country’s

median age, its urban population level and mobile internet penetration. Hierarchical regressions are

conducted. Our findings reveal that three cultural dimensions, i.e., masculinity/femininity, uncertainty

avoidance and long-term orientation, significantly impact nations’ adoption levels of SNS above and

beyond the effects of median age and urban population level. While there is a growing body of literature

that examines the influence of national culture on the adoption and use of a variety of high-tech innovations

and services mediated by these technologies, our study is among the first to specifically relate cultural

perspectives to country adoption levels of social networking sites using an array of cultural dimensions. We

provide a theoretical framework and supporting empirical evidence to underscore the importance of

understanding how culture impacts consumers’ SNS adoption behavior across countries. Implications from

our findings, limitations and directions for future research are provided.

1 INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that in 2014 global social media users

have now surpassed the 2 billion mark, more than

doubling from where it was just four years ago

(Kemp, 2014; Statista.com, 2015). Social media

plays an increasingly important role in people’s lives.

The digitization of content, proliferation of access

through mobile devices, growing availability of

online retailing and interactive marketing

communication strategies have all contributed to the

phenomenal evolution of the social media landscape.

Firms are responding to these trends by engaging in

strategic marketing initiatives, such as utilizing

multichannel marketing, developing apps, or using

novel ways to make their brands more accessible,

engaging and shoppable via SNS. A recent study

conducted by Van Belleghem (2011) revealed that

more than half of users were following brands on

social media and preferred to share their positive

brand experiences on this media. Both of these

activities have been shown to strongly influence

brand perceptions and buying intentions.

SNS provide virtual online contexts where

individuals can communicate, interact, share and

exchange content with others, overcoming the

temporal and geographic boundaries that may

separate them (Sawyer, 2011). Chen and Zhang

(2010) have noted that new media and globalization

have converged to compress time and space, thereby

transforming the world into a smaller interactive

field.

Despite the apparent appeal of SNS, country

adoption rates and the manner by which the

populace engages with SNS vary considerably. For

example, Van Belleghem (2011) found that the

population of countries in emerging markets like

Brazil, China and India had higher awareness,

participated in more networks and had higher daily

usage rates than those from many countries in

Western Europe. Even though the overall Internet

penetration in emerging markets is still somewhat

lower than in developed nations, the consumers from

these countries who are online ostensibly have a

higher level of social media engagement. A recent

report from Forrester (Nielsen, 2012) revealed that

social media users in the West prefer to consume

content more than create it. Despite having the

longest access to social media, online users in North

America and Western Europe appear to have much

more passive attitudes toward it. In addition to the

apparent differences across global regions, there is

233

L. Stump R. and Gong W..

Social Networking Sites: An Exploration of the Effect of National Cultural Dimensions on Country Adoption Rates.

DOI: 10.5220/0005509002330245

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on e-Business (ICE-B-2015), pages 233-245

ISBN: 978-989-758-113-7

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

also considerable variation within regions

themselves. In Asia, Japan has a 35 percent SNS

penetration rate, while Indonesia, China, and India

all boast rates above 60 percent (eMarketer.com,

2012). Nielsen (2012) suggests that Japan may not

follow the emerging Asian social media patterns

because aspects of Japanese culture carry through to

social media preferences, i.e., Japanese consumers

have a greater preference for online anonymity.

Such unevenness in SNS country penetration

rates and usage patterns implies that we still need to

develop a better understanding the potential impact

of culture on the adoption and use of SNS. From

both macro-marketing and micro-marketing

perspectives there are additional reasons for

focusing research attention on this phenomenon.

One consideration is the reciprocal relationship

between technology and quality of life (United

Nations Development Programme 2008; Hill and

Dhanda 2004). Another is marketing’s influence on

consumer satisfaction and well-being (Pan et al.,

Sheng 2007). Consequently, marketers are

increasingly seeking new ways in which consumer-

brand engagement can be formed, nurtured and

sustained across multiple potential touch points,

especially via virtual interactions (Schultz and

Peltier, 2013). Building on past investments in

websites and e-commerce, new investments in social

media platforms, mobile apps, payment systems and

other emerging technologies have the potential to

facilitate consumers sharing and exchanging of

knowledge; to create or enhance functional, time,

place and information utilities; and thus enhance

customer satisfaction and perceived quality of life

for people around the globe.

With the advent of social media comes the

growing interest in conducting research on it by both

academics and practitioners (Schultz and Peltier,

2013; Tsai and Men, 2012). This growing literature

spans a wide range of affiliated topics, including

users’ experiences and gratifications (Dunne et al.,

2010; Palmer and Koenig-Lewis, 2009; Raacke and

Bonds-Raacke, 2008), perceived ease of use and

perceived usefulness of SNS (Pinho and Soares,

2011), branding impact of user-generated content

(UGC) and eWOM on SNS (e.g., Christodoulides et

al., 2012; Goodricha and De Mooij, 2013, Jansen et

al., 2009; Lin et al., 2012), evaluation and

measurement of consumer-brand engagement of

SNS (e.g., Dix, 2012; Gambetti and Graffigna, 2010;

Keller, 2010; LaPointe, 2012; Quinton and

Harridge-March, 2010; Schultz and Block, 2012;

Singh and Sonnenburg, 2012, Trueman et al., 2012;

Valette-Florence et al., 2011), perceived risk and

privacy disclosure behavior on SNS (Xu et al., 2013),

cultural distinctive appeals on SNS (Tsai and Men,

2012), etc. As this inventory suggests, studies

exploring the relationship between culture and

online networking behavior have not been featured

prominently in the extant research literature.

Reflecting the several calls by researchers (e.g.,

Goodricha and De Mooij, 2013; Ribiere et al., 2010;

Rosen et al., 2010; Steers et al., 2008) to address this

gap, we explore cultural explanations for why the

populations of many countries are lagging behind

others with regard to the adoption and use of SNS.

Thus, the intent of the present study is to determine

whether and how cultural factors influence the

country adoption rates of SNS and the usage patterns

of populations, specifically average time spent on

social media.

In the following sections, we first elaborate on

the theoretical background upon which our research

hypotheses are formulated. Specifically, both the

diffusion of innovations literature and Hofstede’s

national culture framework (2001) frame our

investigation into the adoption and use of SNS. Next,

methodological procedures are outlined, along with

and empirical test of our hypotheses using secondary

data for 30 countries that have been drawn from

several reputable sources, including We Are Social

Inc. (wearesocial.com), The Hofstede Centre (geert-

hofstede.com) and CIA World Fact Book. After a

discussion of the results, we conclude with

implications and directions for future research.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW AND

HYPOTHESES

2.1 Social Networking Sites (SNS)

The explosive growth of online social media use

worldwide is indicative that SNS have become one

of the most prominent social computing applications

in the Web 2.0 era (European Commission, Joint

Research Centre, Institute for Prospective

Technological Studies, 2009). Kaplan and Haenlein

(2010, p. 60) define social media as “a group of

Internet-based applications and technological

foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation

and exchange of User Generated Content.” SNS are

web-based services that allow individuals to (1)

construct a public or semi-public profile within a

bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users

with whom they share a connection, and (3) view

and traverse their list of connections and those made

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

234

by others within the system. Consequently, SNS

enable users to build personal profiles, publish

information, promote dialogues, and share networks,

experiences and knowledge within a defined system

(Boyd and Ellison, 2008; Constantinides and

Fountain, 2007). Many users of SNS are active

content generators and critics, rather than merely

being passive content consumers. SNS have shown

great potential to influence the way people socialize,

entertain, shop, acquire and consume information

and make decisions. Marketers, in turn, have

increasingly turned to marketing strategies that

allows them to monitor and shape users’ online

communications on SNS while also engaging

consumers with their brands in a more active,

voluntary and interactive fashion.

2.2 Adoption of Technological

Innovations

Diffusion of innovations (DOI) theory explains how

adoption takes place over time within a social

system. The adoption rate of an innovation is

influenced by (1) characteristics of the innovation

itself, (2) the communication channels through

which the benefits of the innovation are

communicated, (3) the time elapsed since the

introduction of the innovation and (4) the social

system in which the innovation is to diffuse (Rogers,

1983). While it has been common to use individuals

as the unit of analysis in adoption studies, the system

level can also be used. Studies embracing the system

level, consider the nature of a social system and the

relative extent to which an innovation is adopted

within communities, countries, or other social units

having different macroenvironmental characteristics

(e.g., economic, demographic, technological and

cultural factors). These factors can be used to

compare the adoption rates of different innovations

as well as the relative extent to which particular

innovations are adopted across social units with

varying macroenvironmental conditions. Culture can

play an implicit or explicit role in such comparisons

(Maitland and Bauer, 2001) and the diffusion of

innovations can be envisioned as a prolonged

process through which the new culture element(s) is

(are) presented to the society, then accepted by its

people and further integrated into a preexisting

culture (Dearing, 2009).

2.3 Culture

Culture has been described and defined in many

ways. Geertz (1973) labels it as the fabric of

meaning through which people interpret events

around them. Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner

(1998) depict it as the manner in which a group of

people solves problems and reconciles dilemmas.

Hofstede (2001) describes it as the collective mental

programming of a people that distinguishes them

from others. Common to all of these definitions is

the notion that while culture may be abstract it is

characterized by shared values and norms and

mutually reinforcing patterns of behavior (Steers et

al. 2008). Culture is learned and evolves over time

(Hofstede and Bond, 1988; McCort and Malhotra,

1993; Ward et al., 1987). However, culture does

have definite characteristics that are observable and

amenable to empirical description (Strauss and

Quinn, 1992; Rohner, 1984).

One may conceive of culture in terms of its parts,

components, functional segments or institutions,

such as the economic system, the family, education,

religion, government and social control, language

and communication, and transformation and

technology (Baligh, 1994; Chanlat and Bedard, 1991;

Culpan, 1991; Ferraro, 1990; Hall and Hall, 1987

and 1990). To the individual consumer, these social,

economic, and institutional structures and related

macroenvironmental influences determine the

overall context, or “objective reality,” in which he or

she makes a purchasing decision. Beliefs, values,

logic and decision rules are also basic components

of a culture. They are internalized and constitute the

“subjective reality” of the individual consumer, i.e.,

personal values are heavily influenced by cultural

values since individuals are expected to abide by the

values that are promoted in their society as being

important and useful (Clawson and Vinson, 1978;

Patwardhan, 2013). Hence, culture can be seen as

being an underlying framework, consisting both of

the objective reality, as manifested in societal

institutions, and the subjective reality, which

comprise socialized predispositions and beliefs that

guides individuals’ perceptions of observed events

and personal interactions, and the selection of

appropriate responses in social situations (Johansson,

1997). In sum, an individual’s behavior is both a

component and a reflection of the culture in which

they are embedded (Baligh, 1994).

As noted by Cheng and Wong (1996), culture

influences the social construction of phenomena,

such as meanings and practices. Learning, too, is a

fundamentally cultural endeavor, i.e., humans learn

norms through imitation or by observing the process

of reward and punishment in a society of members

who adhere to or deviate from the group's norms

(Engel et al., 1995). Furthermore, meanings, values,

SocialNetworkingSites:AnExplorationoftheEffectofNationalCulturalDimensionsonCountryAdoptionRates

235

ideas and beliefs of a social group are articulated

through various cultural artifacts, such as products,

information and communication technologies

(Hasan and Ditsa, 1999).

2.4 Hypotheses of National Culture and

Adoption of Technological

Innovations

Hofstede (1991) argues that people share a collective

national character that represents their cultural

mental programming, which in turn shapes

individuals’ values, beliefs, assumptions,

expectations, attitudes and behaviors. Hofstede

initially identified four dimensions along which

national cultures vary: power distance, uncertainty

avoidance, individualism vs. collectivism, and

femininity vs. masculinity (Hofstede, 1980 and

2001). More recently Hofstede has expanded his

taxonomy to include long-term vs. short-term

orientation and indulgence vs. restraint and provides

ratings on these dimensions for many countries

(Hofstede, 2015-a & b).

In recent years numerous studies have employed

Hofstede’s framework (e.g., Dwyer et al., 2005;

Ganesh et al., 1997; Kumar and Krishnan, 2002; La

Ferle et al., 2002; Tellis et al., 2003; Van

Everdingen and Waarts, 2003; Yeniyurt and

Townsend, 2003). For example, the study done by

La Ferle and colleagues (2002) examined the

adoption of the Internet in Japan versus the United

States and found that differences on cultural

dimensions explained some of the variance in

Internet penetration and patterns of adoption, even

though Japan and the U.S. share similar

characteristics in terms of economic conditions,

literacy rates and technological infrastructure.

Yeniyurt and Townsend (2003) found a strong

association between the cultural dimensions and the

penetration rates of new high-tech products (i.e., the

Internet, Cellular phones and PCs) and that this

relationship was moderated by social-economic

variables.

Rather than restricting our attention to

individualism vs. collectivism and femininity vs.

masculinity, the two cultural dimensions that past

research has indicated to be relevant to users’ online

communication behaviors (e.g., Goodricha and De

Mooij, 2013; Rosen et al., 2010) the current study

encompasses all six. Drawing on the extant

literature, we posit a rationale for each below.

Individualism-Collectivism is one of the most

widely studied dimensions in cross-cultural research

(Gudykunst, 1998; Kim et al., 1994; Triandis, 1989;

Triandis et al,. 1988; Zhang and Gelb, 1996). This

dimension describes the relation between the group

and the individual. Individualist cultures are

characterized by a loosely knit social framework in

which individuals focus on taking care of themselves

and their immediate family. Personal freedom is

valued and individual decision-making is

encouraged in societies found toward the

individualistic end of the spectrum (Singh et al.,

2003). In contrast, members from collectivistic

societies are apt to be integrated into stronger, more

cohesive groups. Relatives and others in this

extended social group are expected to look after

individuals within them in exchange for obedience

and loyalty. Obligations and group harmony come

before individual aspirations or goals in collectivist

cultures (De Mooij, 1998).

Members of individualist cultures tend to exhibit

more favorable attitudes toward differentiation and

uniqueness (Aaker and Maheswaran, 1997). An

individual’s identity is largely defined by one’s role

in various social relationships. Social networking

can be used to heighten one’s identity, especially

social identity, via self-expression and extra self-

awareness. (Rosen et al. (2010) found a propensity

to engage in more attention-seeking behaviors via

SNS in individualistic cultures. They also reported

that social media users from more individualistic

cultural backgrounds (1) have larger networks of

friends on SNS, (2) whose networks include a

greater proportion of friends who have not been met

face-to-face, and (3) share more photos online, as

opposed to users who identify with more collectivist

cultural backgrounds.

It is important to note that while people in

individualist cultures seem to have more freedom to

try new things than those in collectivistic societies,

members from collectivistic societies may be more

inclined to join and participate in SNS to gain a

sense of belonging, fulfill group obligations and

achieve group harmony. Gangadharbatla (2008)

provided evidence that the need to belong has a

positive effect on a person’s attitude toward SNS

and willingness to join them. Kim and Yun (2007)

found that most Koreans who participated in the

SNS were doing so to keep close ties with a small

number of friends instead of befriending new people.

This juxtaposition is in line with the extant research

that distinguishes between two processes that

explain diffusion, i.e., innovation and imitation.

Populations from individualistic countries appear to

be quicker to adopt in the early stages, whereas

collectivistic countries have adoption rates that are

greater in the later stages, which may be indicative

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

236

of when enough of a critical mass of adopters exist

(Lee et al., 2013; Peng and Mu 2011).

Based on the above discussion, plausible

theoretical arguments can be made for both

individualism and collectivism. Given the lack of a

preponderance of evidence to substantiate one

perspective, we pose the following competing

hypotheses:

H1: Nations whose cultures represent

higher levels of individualism (IDV) will

show higher adoption rates of SNS.

H2: Nations whose cultures represent

higher levels of collectivism will show

higher adoption rates of SNS.

Masculinity-Femininity addresses the extent to

which a society is characterized by assertiveness

versus nurturance and is closely related to societal

expectations of gender roles. Masculine cultures

value achievement and material success more and

also tend to have clear role distinctions between

males and females. In contrast, feminine cultures

value relationships, caring, and are not apt to have

such rigid gender roles (Hofstede, 1980 and 2001).

Although SNS can serve a utilitarian purpose and

foster commercial pursuits, which is likely to be

aligned with masculine cultures where material

things and career advancement are highly valued,

the social aspects of SNS can be expected to be

more germane in feminine cultures where the

nurturing of personal relationships is more cherished

(Ribiere et al., 2010; Singh 2006). Pew Internet &

American Life Project (Pewinternet.org, 2012)

reports that women have been significantly more

likely to use SNS than men since 2009 (Brenner,

2012). Hargittai (2007) found that women were not

only more likely to use SNS than men but also more

likely to embrace different services such as

Facebook, MySpace, and Friendster. Sveningsson

Elm (2007) reported more women than men

emphasized their relationships and expressed

stronger feelings about them in an online meeting

place. Joinson (2008) found women used SNS more

to explicitly foster social connections. Jones and his

colleagues (2008) reported significant differences on

blog usage between genders, with female users

being more likely to use the blog feature available

on MySpace and write about their family, romantic

relationships and health than male users. In a series

of studies of the social networking website MySpace,

Thelwall (2008 and 2009) and his colleagues (2010)

reported that females were likely to give and receive

more positive comments than were males, which

suggests females have a greater ability to textually

harness positive affect. Together, the research above

suggests that systematic differences based on gender

persist in users’ online networking behavior.

Again, given the conflicting theoretical

arguments, we pose competing hypotheses:

H3: Nations whose cultures represent higher

levels of masculinity (MAS) will show higher

adoption rates of SNS.

H4: Nations whose cultures represent higher

levels of femininity will show higher

adoption rates of SNS.

Power distance is the extent to which the less

powerful individuals of a society (and less powerful

members of organizations and institutions within

that society) accept and expect that power will be

distributed unequally. This view of a society's level

of inequality is embraced by followers as well as by

leaders (Hofstede, 1980 and 2001). Singh (2006)

notes that the dimension of power distance has been

found to be inversely related with individualism,

which suggests the following:

H5: Nations whose cultures represent

higher levels of power distance (PDI) will

show lower adoption rates of SNS.

Uncertainty avoidance represents a society's

tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity (House et al.

2004). It can be shown by the degree of comfort or

discomfort in novel, unknown, surprising, or unusual

situations. Uncertainty avoidant societies tend to be

distrustful of new ideas and stick to historically

tested patterns of behavior. They are more prone to

have strict laws and rules, safety and security

measures, and philosophical and religious beliefs

that tend toward absolute “truth”. Conversely,

uncertainty accepting cultures are more tolerant of

different behaviors and opinions, are likely to have

fewer rules, and tend to be more relativist from

philosophical and religious perspectives (Hofstede,

1980 and 2001; Singh, 2006).

House et al. (2004) contend that uncertainty

avoidance is the cultural dimension that most

strongly correlates with technology adoption. While

uncertainty-avoiding cultures may tend to resist

change, this does not necessarily imply that they are

averse to adopting new technologies (Barron and

Schneckenberg, 2012), but it does appear to

influence timing, i.e., when and how long the

adoption process takes before a significant

penetration level is achieved. For example,

Sundqvist et al. (2005) reported that uncertainty-

avoiding cultures needed more time than

uncertainty-accepting cultures to adopt new

technologies and concluded that the majority

preferred to observe the experiences of early

adopters before they made their technology-

SocialNetworkingSites:AnExplorationoftheEffectofNationalCulturalDimensionsonCountryAdoptionRates

237

implementation decisions. Other researchers (e.g.,

Garfield and Watson, 1998; Hasan and Ditsa, 1999;

Veiga et al, 2001) have found that uncertainty-

avoiding cultures tend to adopt new technologies

later than uncertainty-accepting ones. Taken

together, these findings suggest that imitation may

be the dominant process influencing diffusion in

uncertainty-avoiding cultures. Thus we propose:

H6: Nations whose cultures represent higher

levels of uncertainty avoidance (UAI) will

show lower adoption rates of SNS

Long-term vs. short-term orientation captures

whether a society is oriented towards future rewards,

and thus lauds saving, persistence, and adaptation,

versus those that focus on the past and present,

where national pride, respect for tradition and

traditional values, preservation of face, and fulfilling

social obligations are dominant sentiments (Franke

et al., 1991; Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede and Minkov,

2010; Minkov and Hofstede 2012). Long-term

oriented cultures are more open to new ideas; in

such countries the rate of adoption of new

technologies is expected to be higher than in

countries with cultures that are more short-term

oriented (Erumban and de Jong, 2006; Van

Everdingen and Waarts, 2003). Accordingly, we

hypothesize:

H7: Nations whose cultures represent

long-term orientations (LTO) will show

higher adoption rates of SNS.

Indulgence vs. restraint is the most recently

added dimension to Hofstede’s typology. This

dimension represents whether a society tends to

allow relatively free gratification of basic and

natural human drives, i.e., are oriented toward

enjoying life and having fun. Conversely, a

restrained society constrains gratification of needs

through means of strict social norms (Franke et al.,

1991; Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede, 2015-a; Minkov,

2011). In indulgent cultures people tend to focus

more on individual happiness and well-being.,

Furthermore, time is more important and individuals

perceive themselves to have greater freedom and

personal control. Conversely, in restrained cultures

positive emotions are less freely expressed and

happiness, freedom and leisure are not given the

same importance (MacClachlan, 2013). We thus

propose:

H8: Nations whose cultures represent

higher levels of indulgence (IND) will show

higher adoption rates of SNS.

Control Variables. The diffusion literature

shows that adoption and diffusion process is

influenced by variety of socioeconomic factors and

the economic and technological infrastructure of a

country may have a concrete and direct

manifestation of a culture’s impact on consumer

behavior (Yeniyurt and Townsend, 2003). Thus we

also include other country-level variables in our

model to empirically account for extraneous factors

that may influence adoptions levels. These include:

a nation’s mobile Internet penetration, urban

population and the median age of the nation.

Dutta and Bilbao-Osorio (2012) argue that the

world is becoming hyperconnected, fueled by the

exponential growth of mobile devices, big data and

social media. Mobile broadband has become the

primary method of access for people around the

world (Bold and Davidson, 2012). Therefore, the

penetration rate for mobile Internet is included to

account for its impact on access to and use of SNS.

Drawing on urban density theory, SNS may

benefit from easier and cheaper access to ICT

(information and communications technologies)

infrastructure because adoption costs are likely to

decrease when population size and density increase

(Forman, 2005; Billon et al., 2009). Reino, Frew

and Albacete-Saez (2010) have reported that rural

businesses tend to have weaker technology adoption

than those located in urban settings, which suggests

that access, scale economies and associated cost

structures may be the underlying reasons. Hence, a

nation’s urban population is included to account for

the potential influence derived from the inherently

greater market potential, deployment and marketing

efforts on the part of mobile providers.

The literature also suggests that young people are

more favorably disposed toward change (Schiffman

and Kanuk 2003) and have been found to be more

receptive to new ICT innovations such as the mobile

phone and ICT-mediated services such as ATMs and

Internet banking (Eastin 2002). Teens and young

adults have been consistently reported to have

highest wireless and SNS usage rates

(pewinternet.org, 2013). We posit that nations with a

relatively young population should be more

receptive to adoption since country-level penetration

rates are effectively an aggregation of individual

consumption decisions. Thus we include the median

age of a nation as our final control variable.

3 METHODOLOGY AND

FINDINGS

This study examines culture’s impact on global

adoption and use of SNS. Since it is a challenge to

collect data for a multivariate analysis on a global

scale, we utilize secondary data from reputable

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

238

sources, namely Hofstede’s (2001) cultural

dimension scores, We Are Social’s ‘Digital, Social

and Mobile in 2015 Report’ for global social media

penetration rates and mobile Internet penetration

data (Kemp, 2015), and the CIA World Factbook for

a nation’s median age and urban population data

(CIA, 2014). Altogether, data are available for 30

countries. The list of countries in this study is

available from the authors.

The hypotheses regarding the effects of the six

cultural dimensions were tested in a hierarchical

fashion using ordinary least squares (OLS)

regression. In the Baseline Model, the main effects

of the three control variables were assessed. In the

Full Model, the main effects of the six cultural

dimensions were then added and the model was re-

estimated. The significant overall F values in all

models are indicative that interpretation of the

individual regression models and parameter

estimates for the independent variables are

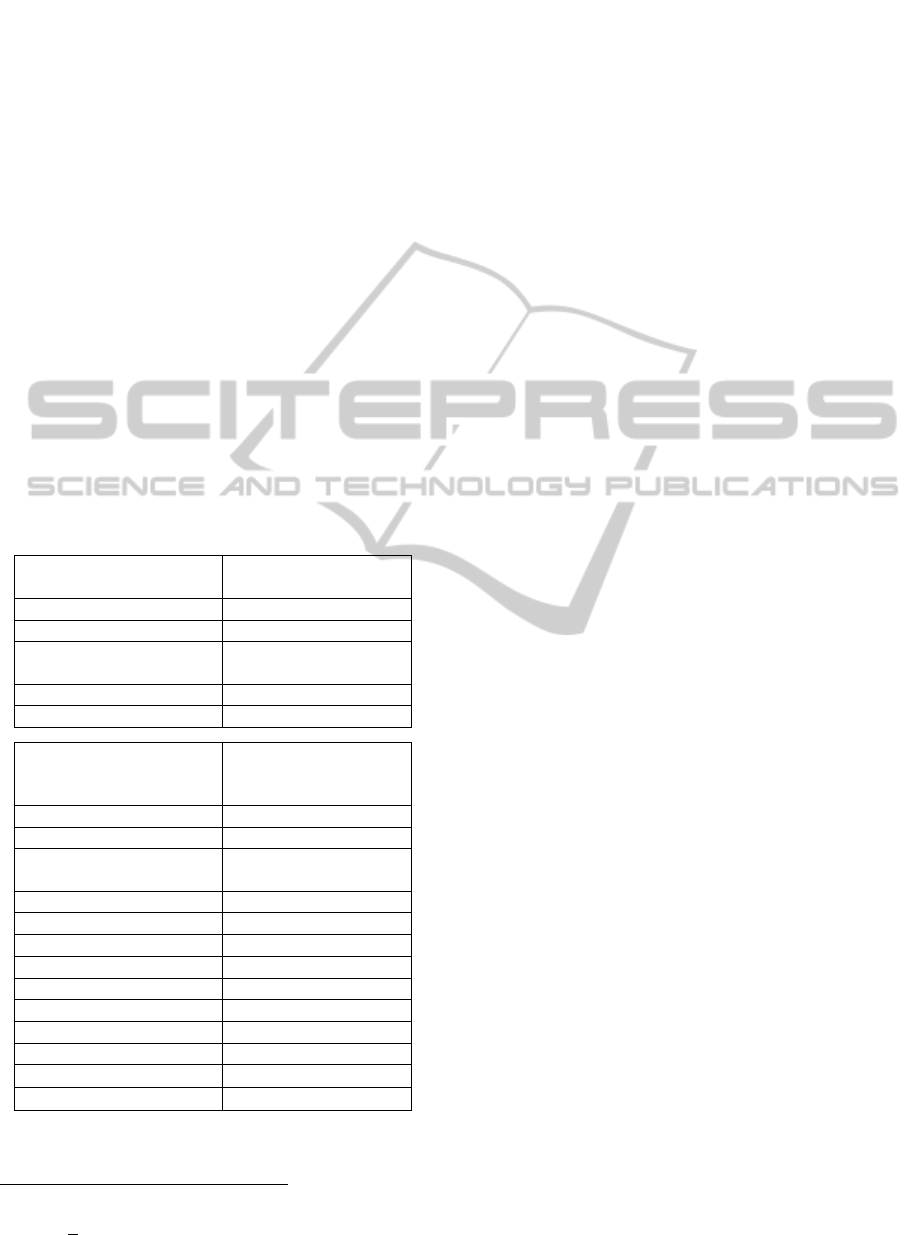

warranted. Regression results are displayed in Table

1.

Table 1: Regression Results (Standardized Coefficients &

t-Values Shown).

1

DV: Adoption Rate of

SNS

Baseline (Control

Variables Only)

Urban Population 2014 .03 0.15 ns

Median Age 2014 .08 0.42 ns

Mobile Internet

Penetration 2014

.46 2.26 **

F-value

(df1,df2)

F

(3,26)

= 4.90*

R

2

(Adjusted R

2

) .36 (.29)

DV: Adoption Rate of

SNS

Full (Control &

Substantive

Predictors)

Urban Population 2014 .56 3.19 *

Median Age 2014 .90 3.50 *

Mobile Internet

Penetration 2014

-.16 -0.91 ns

IDV (H 1-a & H 2-a) -.25 -1.19 ns

MAS (H 3-a & H 4-a) -.31 -2.42 **

PDI (H 5-a) .27 1.30 ns

UAI (H 6-a) -.44 -3.49 *

LTO (H 7-a) -.69 -3.54 *

IND (H 8-a) .23 1.45 ***

F-value

(df1,df2)

F

(9,19)

= 5.98*

R

2

(Adjusted R

2

) .74 (.62)

F-value

F

(6,19)

= 4.59 *

R

2

R

2

= .38

As we can see from Table I, the coefficients of three

of the cultural variables, i.e., masculinity/femininity

1

Significance levels (one-tailed test) * = p < .01; ** = p < .05;

*** = p < .10; ns = not significant

(MAS), uncertainty avoidance (UAI) and long-term

orientation (LTO) were significant and another,

indulgence (IND), was marginally significant in the

Full Model. Moreover, the addition of the main

effect terms relating to the cultural dimensions

resulted in a significant improvement in the

explanatory power of the model, i.e., R

2

showed a

significant improvement by increasing from .36 to

.74. Based on these results, we conclude:

Neither hypotheses 1 or 2 were supported;

individualism/collectivism (IDV) was found to

be non-significant.

Hypothesis 4 was supported, while hypothesis

3 was refuted. Masculinity/femininity (MAS)

was found to be significant, but negative,

which is consistent with the social rationale for

SNS rates to be higher in feminine cultures.

Hypothesis 5 was not supported; power

distance (PDI) was found to be non-significant.

Hypothesis 6 was supported; uncertainty

avoidance (UAI) was found to be significant

and negative, which means that lower SNS

adoption rates were found in nations that were

more uncertainty avoidant.

Hypothesis 7 was not supported; although

long-term orientation (LTO) was found to be

significant it was negative, which is contrary to

our expectation. This result suggests that short-

term oriented cultures had higher SNS

adoption rates.

Hypothesis 8 was marginally supported; as

expected, indulgence (IND) was found to be

positive although only significant at the p <

.10, which suggests that higher SNS adoption

rates are found in more indulgent cultures.

Two of the control variables, median age and

urbanization, were found to be significant and

positive.

4 DISCUSSION

Overall, the results of our hierarchical regressions support

the general premise that culture does influence the

county adoption rates of SNS and that inclusion of

cultural dimensions provide a significant increase in

the explanatory power of the model beyond merely

considering nations’ social (demographic) and

technical contexts.

Unlike the study by Rosen et al. (2010), this

study revealed no significant impact of

individualism (IDV) on SNS adoption, thus failing

to support either of the competing hypotheses we

posed (H 1 and H 2). One possible explanation,

SocialNetworkingSites:AnExplorationoftheEffectofNationalCulturalDimensionsonCountryAdoptionRates

239

given the small sample size of countries, is that this

effect may be relatively weak and we simply did not

have enough power for the apparent negative effect

to achieve significance. Another potential reason

could be that both innovation and imitation

processes are taking place and cancelling out one

another.

Finding support for Hypothesis 4 over 3 is

indicative that more feminine cultures appear be

more conducive to adopting SNS than those that are

more masculine (MAS). This is in line with other

studies that have reported that women typically

outnumber men on SNS and tend to use SNS more

than men and for different and more social purposes

(Hampton et al., 2011; Koetsier, 2012; Joinson, 2008;

Van Belleghem, 2011).

We found no significant impact of power

distance (PDI) on SNS adoption, thus failing to

support Hypothesis 5. Consequently the role of this

cultural dimension on the adoption of SNS remains

equivocal.

Empirical support for Hypothesis 6, i.e.,

uncertainty avoidance (UAI) was found to be

significant and negative, is consistent with the

premise the adoption of SNS is apt to be higher in

uncertainty accepting cultures where different

behaviors and opinions are more likely to be

tolerated (Hofstede, 1980 and 2001; Singh, 2006).

SNS, with the ability to create and share content,

provides a platform for self-expression with less risk

to the originator.

Our lack of support for Hypothesis 7, which

related to long-term orientation (LTO) (i.e., the

significant but negative coefficient), was unexpected

given an abundance of empirical research supporting

the proposition that the rate of adoption of new

technologies is expected to be higher in long-term

oriented nations than in countries with cultures that

are more short-term oriented (e.g., Erumban and de

Jong, 2006; Van Everdingen and Waarts, 2003).

While long-term oriented cultures are thought to be

more open to new ideas and more adaptive, the

emphasis on fulfilling social obligations in short-

term oriented societies (Hofstede, 2001; Minkov,

2010) may foster the adoption of SNS since this is a

medium that enables the conveyance of richer, more

nuanced messages beyond the verbal or written word.

Thus, further conceptual development appears to be

warranted.

Although the coefficient for indulgence (IND)

was in the expected positive direction (Hypothesis 8),

it was only marginally significant (p < .10), thus

providing weak support for the premise that more

indulgent cultures will have higher SNS adoption

rates.

5 IMPLICATIONS,

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE

RESEARCH

Culture influences people’s beliefs and values,

which in turn, shape their behaviors. The effect of

the cultural environment is important in the sense

that it determines the unique social values of the

population of a particular country (Fields, 1983),

which may foster or retard the adoption of

technological innovations, including SNS. Hence,

marketing activities related to the commercial

introduction of these innovations need also be

culturally nuanced (Takada and Jain, 1991). As

Schultz and Peltier (2013) have observed, research is

still at an embryonic stage despite the growing

attention to social media marketing. Our results

underscore the need to further explore how cultural

factors influence people’s adoption and SNS.

Individuals can and do use SNS to present

themselves and interact with others, including

businesses.

This study constitutes a novel contribution to the

literature and further enhances our understanding of

the importance of cultural influences on consumers’

adoption of SNS. Overall, our results are intriguing

since they do provide evidence of culture’s role in

influencing country adoption rates of SNS.

Moreover, this study is one of the few to take a

comprehensive approach and include all six of the

cultural dimensions that are prominent in the

conceptualizations of Hofstede (1980 and 2001),

House et al. (2004) and. Minkov (2010) as

predictors.

Our results suggest that international marketers,

nongovernmental organizations (NGO) and/or

government bodies should use culturally-sensitive

criteria when determining which social media

platforms to employ to communicate with particular

country or regional markets and in the design of

messages used to interact with targeted segments.

Communication materials are key carriers of cultural

values (Cheong et al., 2010), which implies that the

degree to which social marketing strategies and

tactics align with a culture may be an important

determinant of the relative success or failure of those

efforts in a particular country. Promotional messages

on SNS can play an essential role in communicating

with targeted audiences and heightening their

engagement with a brand, an entity or an initiative.

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

240

Cultural characteristics can also be used as screening

criteria for selecting countries where marketers

might more heavily employ social media strategies

versus using more traditional media, not only to

promote products, but also to support learning,

social inclusion, health and governance (European

Commission, Joint Research Centre, Institute for

Prospective Technological Studies, 2009).

We would be remiss if we did not acknowledge

the limitations to this study. One is to recognize our

reliance on secondary data obtained from different

sources, which has been criticized for being

inconsistent and unreliable (Yeniyurt and Townsend,

2003). Another is the limited sample size and cross-

sectional design. Due to the limited availability of

the data, only one year adoption rates for a limited

number of countries were included. To enhance the

generalizability of the results of this research, time-

series data for a larger sample of nations

representing greater diversity are required in order to

form more conclusive ideas about the adoption and

diffusion of SNS across countries.

Another limitation is that we only employed a

main effects model. Thus we are not able to address

whether these cultural dimensions operate

independently of one another or in a contingent

fashion to enhance or retard the adoption of SNS in

particular countries. Furthermore, we implicitly

assume that the effect of these cultural dimensions is

linear, rather than curvilinear. Thus additional

conceptual development and empirical research is

warranted.

Despite these limitations, our study has provided

new insights about how cultural differences

influence the country-level adoption rates of social

networks. We hope further research in cross-cultural

comparisons about the role and effects of cultural

factors on the adoption and use of SNS will follow.

REFERENCES

Aaker, J. & Maheswaran, D. 1997, ‘The effect of culture

orientation on persuasion’, Journal of Consumer

Research, vol. 24, December, pp. 315-328.

Averya, E., Lariscyb, R., Amadorc, E., Ickowitzc, T.,

Primmc, C. & Taylorc, A. 2010, ‘Diffusion of social

media among public relations practitioners in health

departments across various community population

sizes’, Journal of Public Relations Research, vol. 22,

no. 3, pp. 336-358.

Baligh, H. 1994, ‘Components of culture: nature,

interconnections, and relevance to the decisions on the

organization structure’, Management Science, vol. 40,

no. 1, pp. 14-27.

Barron, A. & Schneckenberg, D. 2012, ‘A theoretical

framework for exploring the influence of national

culture on Web 2.0 adoption in corporate contexts’,

Electronic Journal Information Systems Evaluation,

vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 176-186.

Billon, M., Rocio, M., & Lera-Lopez, F. 2009, ‘Disparities

in ICT adoption: A multidimensional approach to

study the cross-country digital divide’,

Telecommunications Policy, vol. 33, pp. 596–610.

Bold, W. & Davidson, W. 2012, ‘Mobile broadband:

Redefining Internet access and empowering

individuals’, in World Economic Forum The Global

Information Technology Report 2012 – Living in a

Hyperconnected World, pp. 67-77.

Boyd, D. & Ellison, N. 2008, ‘Social networking sites:

definition, history, and scholarship’, Journal of

Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 13, no. 1, pp.

210-230.

Brenner, J. 2012, ‘Pew Internet: Social networking’,

Available from: http://pewinternet.org/

Commentary/2012/March/Pew-Internet-Social-

Networking-full-detail.aspx, [25 January, 2015].

Chanlat, A. & Bedard, R. 1991, ‘Managing in the Quebec

style: originality and vulnerability’, International

Studies of Management & Organization, vol. 21, no. 3,

pp.10-37.

Chen, G. & Zhang, K. 2010, ‘New media and cultural

identity in the global society’, in Handbook of

Research on Discourse Behavior and Digital

Communication: Language Structures and Social

Interaction, ed. R. Taiwo, Idea Group Inc., Hershey,

PA, pp. 801-815.

Cheng, K. & Wong, K. 1996, ‘School effectiveness in East

Asia: Concepts, origins and implications’, Journal of

Educational Administration, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 32-49.

Cheong, Y., Kim, K. & Zheng, L. (2010) ‘Advertising

appeals as a reflection of culture: a cross-cultural

analysis of food advertising appeals in China and the

US’, Asian Journal of Communication, vol. 20, no. 1,

pp.1-16.

Christodoulides, G., Jevons, C. and Bonhomme, J. (2012)

‘Memo to marketers: Quantitative evidence for change

- how user-generated content really affects brands’,

Journal of Advertising Research, 52, 1, 53-64.

CIA 2014, The World Factbook – Median age, Available

from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-

world-factbook/fields/2177.html, [25 January, 2015].

Clawson, J., & Vinson, D.E. (1978). ‘Human values: A

historical and interdisciplinary analysis’ in Advances

in Consumer Research, ed. K. Hunt (Ed.), Association

for Consumer Research, Ann Arbor, MI, pp. 396-402.

Constantinides. E. & Fountain, S. 2007, ‘Web 2.0:

Conceptual foundations and marketing issues’, Data

and Digital Marketing Practice, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 231-

44.

Culpan, R. 1991, ‘Institutional model of comparative

management’, Advances in International Comparative

Management, JAL Press Inc., Greenwich, CT, vol. 6.

Pp. 127-142.

De Mooij, M. 1998, Global Marketing and Advertising:

SocialNetworkingSites:AnExplorationoftheEffectofNationalCulturalDimensionsonCountryAdoptionRates

241

Understanding Cultural Paradoxes. Sage Publications,

Thousand Oaks, CA.

Dearing, J. 2009, ‘Applying diffusion of innovation theory

to intervention development’, Available from:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/

PMC2957672/, [25 January, 2015].

Dix, S. 2012, ‘Introduction to the special issue on social

media and mobile marketing’, Journal of Research in

Interactive Marketing, Vol. 6, no. 3, p. 164.

Doster, L. (2008) ‘Millennial teens design their social

identity via online networks’, Academy of Marketing

Conference Proceedings, Aberdeen, July.

Dunne, Á., Lawlor, M-A & Rowley, J. 2010, ‘Young

people's use of online social networking sites - a uses

and gratifications perspective’, Journal of Research in

Interactive Marketing, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 46-58.

Dutta, S. & Bilbao-Osorio, B. 2012, ‘The global

information technology report 2012 – Living in a

hyperconnected world’, INSEAD & World Economic

Forum, Available from: http://www3.weforum.org/

docs/Global_IT_Report_2012.pdf, [25 January, 2015].

Dwyer, S., Mesak, H. & Hsu M. 2005, ‘An Exploratory

Examination of the Influence of National Culture on

Cross-National Product Diffusion’, Journal of

International Marketing, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 1-27.

Eastin, M. 2002, ‘Diffusion of e-commerce: An analysis

of the adoption of four e-commerce activities’,

Telematics and Informatics, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 251-

267.

eMarketer.com 2012, Social media penetration in Asia-

Pacific countries, Available from: http://trends.e-

strategyblog.com/2012/05/03/social-media-penetration

-in-asia-pacific-countrieschart/356, [25 January, 2015].

Engel, J., Blackwell, R. & Miniard, R. (1995), Consumer

Behavior, 8

th

ed., The Dryden Press, Harcourt Brace

College Publishers, Fort Worth, TX.

European Commission's Joint Research Centre Institute

for Prospective Technological Studies 2009, The

impact of Social Computing on the European Union

Information Society and Economy, eds. Punie, Y. et al.,

Available at: http://ftp.jrc.es/EURdoc/JRC54327. pdf,

[26 May, 2015].

Erumban, A & De Jong, S. 2006,’“Cross-country

differences in ICT adoption – a consequence of

culture?’ Journal of World Business, vol. 41, no. 4, pp.

302-314.

Ferraro, G. 1990, The Cultural Dimension of International

Business, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Fields, G. 1983, From Bonsai to Levi’s. Macmillan

Publishing Company, New York.

Forman, C. 2005, ‘The corporate digital divide:

Determinants of internet adoption. Management

Science, vol. 51, pp. 641–654.

Franke, R., Hofstede, G. & Bond, M. 1991, ‘Cultural roots

of economic performance: A research note, Strategic

Management Journal, vol. 12, pp. 165-173.

Fraser, M. & Dutta, S. 2008, Throwing sheep in the

boardroom: How online social networking will

transform your life, work and world, Wiley,

Chichester.

Gambetti, R. & Graffigna, G. 2010, ‘The concept of

engagement: A systematic analysis of the ongoing

marketing debate’, International Journal of Market

Research, vol. 52, no. 6, pp. 801-826.

Ganesh, J., Kumar, V., & Subramaniam, V. 1997,

‘Learning effect in multinational diffusion of

consumer durables: An exploratory investigation’,

Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, vol. 25,

no. 3, pp. 214-228.

Gangadharbatla, H. 2008, ‘Facebook me: Collective self-

esteem, need to belong, and Internet self-efficacy as

predictors of the iGeneration’s attitudes toward social

networking sites’, Journal of Interactive Advertising,

vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 5-15.

Garfield, M. & Watson, R. 1998, “Differences in national

information infrastructure: The reflection of national

cultures” Journal of Strategic Information Systems,

vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 313-337.

Geertz, C. 1973, The Interpretation of Cultures. New York:

Basic Books.

Goodricha, K. & de Mooij, M. 2013, ‘How ‘social’ are

social media? A cross-cultural comparison of online

and offline purchase decision influences’, Journal of

Marketing Communications, vol. 20, no. 1-2, pp. 1-

14.

Gudykunst, W. 1998, Bridging differences: Effective

intergroup communication, (3

rd

ed.), Sage Publications,

Thousand Oaks, CA.

Hall, E. 1976, Beyond culture. Anchor Books, New York.

Hall, E. & Hall, M. 1987, Hidden differences: Doing

business with the Japanese. Anchor Books/Doubleday,

New York.

Hall, E. & Hall, M. 1990, Understanding Cultural

Differences, Intercultural Press, Yarmouth, ME.

Hampton, K., Goulet, L.S., Rainie, L. & Purcell, K. 2011,

‘Social networking sites and our lives’, Available from:

http://www.pewinternet.org/~/

media//Files/Reports/2011/PIP%20-%20

Social%20networking%20sites%20 and %20

our%20lives.pdf, [10 July, 2014].

Hargittai, E. 2007, ‘Whose space? Differences among

users and non-users of social network sites’, Journal

of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 13, no. 1,

pp. 276-297.

Harris, J., Snider, D. & Mueller, N. 2013, ‘Social media

adoption in health departments nationwide: The state

of the States’, Frontiers in Public Health Services &

Systems Research, vol. 2, no. 1, article 5.

Hasan, H. & Ditsa, G. 1999, ‘The impact of culture on the

adoption of IT: An interpretive study’, Journal of

Global Information Management, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 5-

15.

Hill, R. & Dhanda, K. 2004, ‘Globalization and

technological achievements: Implications for macro-

marketing and the digital divide’, Journal of

Macromarketing, vol. 24, pp. 147-155.

Hofstede, G. 1991, Cultures and organizations: Software

of the Mind. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Hofstede, G. 2001, Culture’s consequences (2

nd

ed.), Sage

Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

242

Hofstede, G. 2015-a&b, ‘Dimensions of National Cultures

& Research and VSM,’ Available from:

http://www.geerthofstede.com/ dimensions-of-

national-cultures , [27 January, 2015].

Hofstede, G. & Bond, M. 1988, ‘The Confucian

connection: from cultural roots to economic growth’,

Organizational Dynamics, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 5-21.

Hofstede, G. & Minkov, M. 2010, ‘Long- versus short-

term orientation: new perspectives, Asia Pacific

Business Review, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 493–504.

House, R., Hanges, P., Javidan, M, Dorfman, P. & Gupta,

V. 2004. Culture, leadership and organisations – the

GLOBE study of 62 societies, Sage Publications,

Thousand Oaks, CA.

Informationisbeautiful.net 2012, ‘Chicks rule? Gender

balance on social networking sites’, Available from:

http://www.informationisbeautiful.net/

visualizations/chicks-rule/, [25 January, 2015].

Jansen, B., Sobel, K., Cook, G. 2009, ‘Classifying

ecommerce information sharing behavior by youths on

social networking sites’, Journal of Information

Science, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 120-126.

Janssen, F. 2011, ‘How social media confirms what we

know about cultures’, Available from:

http://blog.lewispr.com/2011/09/how-social-media-

confirms-what-we-know-about-cultures.html, [2

January, 2015].

Johansson, J., 1997, Global Marketing, Irwin Book Team,

McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., New York.

Johansson, J. 2003, Global marketing: Foreign entry,

local marketing & global management (3

rd

ed.),

McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York.

Joinson, A. 2008, ‘Looking at, looking up or keeping up

with people?: motives and use of Facebook’, CHI

2008 Proceedings of the twenty-sixth annual SIGCHI

conference on Human factors in computing systems,

pp. 1027–1036.

Jones, S., Millermaier, S., Goya-Martinez, M., & Schuler,

J. 2008, ‘Whose space is MySpace? A content analysis

of MySpace profiles’, First Monday, vol. 13, no. 9,

Available from: http://www.uic.edu/ htbin/cgiwrap/

bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2202/2024, [25

January, 2015].

Kaplan, A. & Haenlein, M. 2010, ‘Users of the world

unite! The challenges and opportunities of social

media’, Business Horizons, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 59-68.

Keller, K. 2010, ‘Brand equity management in a

multichannel, multimedia retail environment’, Journal

of Interactive Marketing, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 58-70.

Kemp, S. 2014, ‘Global social media users pass 2 billion’,

Available from: http://wearesocial.net/

blog/2014/08/global-social-media-users-pass-2-

billion/, [02 January, 2015].

Kemp, S. 2015, ‘Digital, Social and Mobile in 2015,’

Available from: http://wearesocial.net/tag/sdmw/, [27

January, 2015].

Kim, K. & Yun, H. 2007, ‘Crying for me, crying for us:

Relational dialectics in a Korean social network site’,

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol.

13, no. 1, pp. 298-318.

Kim, U., Triandis, H.C., Kagitcibasi, C., Choi, S. & Yoon,

G. 1994, Individualism and Collectivism: Theory,

Method and Applications, Sage Publications,

Thousand Oaks, CA.

Koetsier, J. 2012, ‘Social media demographics 2012: 24

sites including Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn’,

Available from: http://venturebeat.com/2012/08/22/

social-media-demographics-stats-2012/, [25 January,

2015].

Kumar, V., Ganesh, J., & Echambadi, R. 1998, ‘Cross-

National diffusion research: What do we know and

how certain are we?’ Journal of Product Innovation

Management, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 255-268.

Kumar, V., & Krishnan, T. 2002, ‘Multinational diffusion

models: An alternative framework’, Marketing Science,

vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 318-330.

La Ferle, C., Edwards, S.M. & Mizuno, Y. 2002, ‘Internet

diffusion in Japan: Cultural considerations’, Journal of

Advertising Research, Vol. March/April, pp. 65-79.

LaPointe, P. 2012, ‘Measuring Facebook’s impact on

marketing – The proverbial hits the fan’, Journal of

Advertising Research, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 286-287.

Sang-Gun Lee, S.-G., Trimi, S. & Kim, C. 2013, ‘The

impact of cultural differences on technology adoption.’

Journal of World Business, vol. 48, pp. 20–29.

Lin, T., Lu, K-Y, Wu, J-J. 2012, ‘The effects of visual

information in eWOM communication’, Journal of

Research in Interactive Marketing, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 7-

26.

Liu, H. 2008, ‘Social network profiles as taste

performances’, Journal of Computer Mediated

Communication, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 252-275.

Maitland, C. & Bauer, J. 2001, ‘National level culture and

global diffusion: The case of the Internet,” in Culture,

technology, communication: Towards an Intercultural

Global Village, ed. Ess, SUNY Press, New York, pp.

87-128.

MacClachlan, M. 2013, ‘Indulgence vs. restraint – the 6th

dimension,’ Blog posting 11 January, 2013 Available

from: http://www.communicaid.com/ cross-cultural-

training/blog/indulgence-vs-restraint-6th-

dimension/#.VNgMHPnF-So, [8 February, 2015].

McCort, D. & Malhotra, N. 1993, ‘Culture and consumer

behavior: toward an understanding of cross-cultural

consumer behavior in international marketing’,

Journal of International Consumer Marketing, vol. 6,

no. 2, pp. 91-127.

Minkov, M. 2011, Cultural Differences in a Globalizing

World, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, London.

Minkov, M. & Hofstede, G. 2012, ‘Hofstede’s fifth

dimension: New evidence from the world values

survey,’ Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, vol.

43, no. 1, pp. 3-14.

Nielsen 2012, ‘The Asian media landscape is turning

digital. How can marketers maximise their

opportunities?’ Nielsen, New York, NY.

Palmer, A. & Koenig-Lewis, N. 2009, ‘An experiential,

social network-based approach to direct marketing’,

Direct Marketing: An International Journal, vol. 3, no.

3, pp. 162-176.

SocialNetworkingSites:AnExplorationoftheEffectofNationalCulturalDimensionsonCountryAdoptionRates

243

Pan, Y., Zinkhan, G., and Sheng, S. 2007, ‘The subjective

well-being of nations: A role for marketing?’ Journal

of Macromarketing, vol. 27, pp. 360-369.

Patwardhan, A. 2013, ‘Consumers’ intention to adopt

radically new products: A conceptual model of causal

cultural explanation,’ Journal of Customer Behaviour,

vol. 12, no. 2-3, pp. 247-259.

Peng, G. & Mu, J. 2011, ‘Technology adoption in online

social networks,’ Journal of Product Innovation

Management, vol. 28, no. S1, pp. 133–145.

Pewinternet.org 2012, Pew Internet: Mobile, Available

from: http://pewinternet.org/Commentary/2012/

February/Pew-Internet-Mobile.aspx, [25 January,

2015].

Pewinternet.org (2013), Social Media Update 2013,

http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/12/30/social-media-

update-2013/, [25 January, 2015].

Pinho, J. & Soares, A. 2011, ‘Examining the technology

acceptance model in the adoption of social networks’,

Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, vol. 5,

no. 2/3, pp. 116-129.

Quinton, S. and Harridge-March, S. 2010, ‘Relationships

in online communities: the potential for marketers’,

Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, vol. 4,

no. 1, pp. 59-73.

Raacke J and Bonds-Raacke J. 2008, ‘MySpace and

Facebook: Applying the uses and gratifications theory

to exploring friend-networking sites’,

Cyberpsychology & Behavior [serial online], vol. 11,

no. 2, pp. 169-174.

Reino, S., Frew, A. & Albacete-Saez, C. 2010, ‘ICT

adoption and development: issues in rural

accommodation’, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism

Technology Information, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 66-80.

Ribiere, V., Haddad, M. & Wiele, P. 2010, ‘The impact of

national culture traits on the usage of web 2.0

technologies’, The Journal of Information and

Knowledge Management Systems, vol. 40, no. 3/4, pp.

334-361.

Rogers, E. 1983, Diffusion of innovations, The Free Press,

New York.

Rohner, R. 1984, ‘Toward a conception of culture for

cross-cultural psychology’, Journal of Cross-Cultural

Psychology, vol. 15, pp. 111-138.

Rosen, D., Stefanone, M. & Lackaff, D. 2010, ‘Online and

offline social networks: Investigating culturally-

specific behavior and satisfaction’, IEEE, Proceedings

of the 43rd Hawaii International Conference on

System Sciences, pp. 1-10.

Sawyer, R. 2011, ‘The impact of new social media on

intercultural adaptation’, Available from:

http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?arti

cle=1230&context=srhonorsprog, [02 January, 2015].

Schiffman, L. & Kanuk, L. 2010, Consumer Behaviour,

10th edition, Pearson, New York.

Schultz, D. & Block, M. 2012, ‘Rethinking brand loyalty

in an age of interactivity’, Journal of Brand

Management, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 21-39.

Schultz, D. & Block, M. 2012, ‘Rethinking brand loyalty

in an age of interactivity’, Journal of Brand

Management, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 21-39.

Schultz, D. & Peltier, J. 2013, ‘Social media’s slippery

slope: Challenges, opportunities and future research

directions’, Journal of Research in Interactive

Marketing, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 86-99.

Singh, S. 2006, ‘Cultural differences in, and influences on,

consumers’ propensity to adopt innovations’,

International Marketing Review, vol. 23, no. 2, pp.

173-191.

Singh, S. & Sonnenburg, S. 2012, ‘Brand performances in

social media’, Journal of Interactive Marketing, vol.

26, no. 4, pp. 189-197.

Singh, N., Zhao, H. & Hu, X. 2003, ‘Cultural adaptation

on the Web: A study of American companies’

domestic and Chinese Websites’, Journal of Global

Information Management, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 63-80.

Statista.com 2015, ‘Number of social network users

worldwide from 2010 to 2018 (in billions)’, Available

from: http://www.statista.com/statistics/

278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/,

[5 January, 2015].

Steers, R., Meyer, A. & Sanchez-Runde, C. 2008,

‘National culture and the adoption of new

technologies,’ Journal of World Business, vol. 43, pp.

255–260.

Stewart, C., Shields, S. & Sen, N. 2001, ‘Diversity in on-

line discussion: A study of cultural and gender

differences in listserves’, in Culture, Technology,

Communication: Towards an Intercultural Global

Village, ed. Ess, SUNY Press, New York, pp. 161-186.

Strauss C. & Quinn, N. 1992, ‘Preliminaries to a theory of

culture acquisition’, in Cognition: Conceptual and

Methodological Issues, eds. Pick H., Van Den Broke,

P. and Knell, D., American Psychological Association,

Washington, D.C., pp. 267-294.

Sundqvist, S., Frank, L., & Puumaliainen, K. 2005, “The

effects of country characteristics, cultural similarity

and adoption timing on the diffusion of wireless

communications”, Journal of Business Research, vol.

58, no. 1, pp.107-110.

Sveningsson Elm, M. 2007, ‘Gender stereotypes and

young people's presentations of relationships in a

Swedish Internet community’, YOUNG, vol. 15, no. 2,

pp. 145–167.

Takada, H. & Jain, D. 1991, ‘Cross-national analysis of

diffusion of consumer durable goods in Pacific Rim

countries’, Journal of Marketing, vol. 55, April, pp.

48-54.

Tellis, G. J., Stremersch, S., & Yin E. 2003, ‘The

international takeoff of new products: The role of

economics, culture, and country innovativeness’,

Marketing Science, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 188-208.

Thelwall, M. 2008, ‘Social networks, gender and friending:

An analysis of MySpace member profiles’, Journal of

the American Society for Information Science and

Technology, vol. 59, no. 8, pp. 1321–1330.

Thelwall, M. 2009, ‘Homophily in MySpace’, Journal of

the American Society for Information Science and

Technology, vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 219–231.

Thelwall, M., Wilkinson, D. & Uppal, S. 2010, ‘Data

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

244

mining emotion in social network communication:

Gender differences in MySpace’, Journal of the

American Society for Information Science and

Technology, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 190-199.

Tong, S.T., van Der Heide, B., Langwell, L. & Walther, J.

2008, ‘Too much of a good thing? The relationship

between number of friends and interpersonal

impressions on Facebook’, Journal of Computer-

Mediated Communication, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 531-549.

Triandis, H. 1989, ‘The self and social behavior in

differing cultural contexts’, Psychological Review, vol.

96, no. 3, pp. 506-520.

Triandis, H.C., Bontempo, R., Villareal, M., Asai M. &

Lucca, N. 1988, ‘Individualism and collectivism:

Cross-cultural perspective on self-ingroup

relationships’, Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 323-338.

Trompenaars, F. & Hampden-Turner, C. 1998, Riding the

waves of culture: Understanding diversity in global

business. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Trueman, M., Cornelius, N. & Wallace, J. 2012, ‘Building

brand value online: Exploring relationships between

company and city brands’, European Journal of

Marketing, vol. 46, no. 7/8, pp. 1013-1031.

Tsai, W-H. & Men L. 2012, ‘Cultural values reflected in

corporate pages on popular social network sites in

China and the United States’, Journal of Research in

Interactive Marketing, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 42-58.

United Nations Development Programme 2008, Human

Development Report 2007/08, Table 1, pp. 229-232.

Valette-Florence, P., Guizani, H. & Merunka, D. 2011,

‘The impact of brand personality and sales promotions

on brand equity’, Journal of Business Research, vol.

64, no. 1, pp. 24-28.

Van Belleghem, S. 2011, ‘Social media around the world

2011’, Available from: http://www.slideshare.net/

stevenvanbelleghem/ social-media-around-the-world-

2011, in Sites Consulting, [25 January, 2015].

Van Everdingen, Y.M. & Waarts, E. 2003, ‘The effect of

national culture on the adoption of innovations’,

Marketing Letters, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 2-30.

Veiga, J. F., Floyd, S., & Dechant, K. 2001, ‘Towards

modelling the effects of national culture on IT

implementation and acceptance’, Journal of

Information Technology, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 145-158.

Walther, J., van Der Heide, B., Kim, S-Y, Westerman, D.

& Tong, S. 2008, ‘The role of friends' appearance and

behavior on evaluations of individuals on Facebook:

Are we known by the company we keep?’ Human

Communication Research, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 28-49.

Ward, S., Klees, D. & Robertson, T. 1987, ‘Consumer

socialization in different settings: an international

perspective’, Advances in Consumer Research, vol. 14,

pp. 468-472.

Wearesocial.sg 2014, Global Digital Statistics 2014,

Available from: http://wearesocial.net/blog/2014/ 01/

social-digital-mobile-worldwide-2014/, [25 January,

2015].

Xu, F., Michael, K. & Chen, X. 2013, ‘Factors affecting

disclosure on social network sites: an integrated

model’, Electronic Commerce Research, vol. 13, pp.

131-168.

Yeniyurt, S. & Townsend, J. 2003, ‘Does culture explain

acceptance of new products in a country? An empirical

investigation’, International Marketing Review, vol.

20, no. 4, pp. 377-396.

Zhang, Y. & Gelb, B. 1996, ‘Matching advertising appeals

to culture: The influence of products’ use conditions’,

Journal of Advertising Research, vol. 25, p. 3, pp.

29-46.

SocialNetworkingSites:AnExplorationoftheEffectofNationalCulturalDimensionsonCountryAdoptionRates

245