Building Seniors' Social Connections and Reducing Loneliness

Through a Digital Game

Simone Hausknecht, Robyn Schell, Fan Zhang and David Kaufman

Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Drive, Burnaby, BC, V5A 1S6, Canada

Keywords: Digital Games, Videogames, Older Adults, Seniors, Aging, Social Connectedness, Loneliness.

Abstract: Quality of life is related to social interactions as social connectedness can be an important aspect in older

adults’ sense of well-being. Technology offers many opportunities for older adults to build social

connections and possibly reduce feelings of loneliness. In recent years, investigations into using digital

games for older adults have shown some positive results. This study involved 73 participants in 14 different

centres across a large city in western Canada. The group played in a Wii digital bowling tournament that

lasted for eight weeks. Pre and post-tests were given to measure social connectedness, and loneliness. Semi-

structured interviews then were conducted with 17 participants. Positive results were found for social

connectedness and loneliness.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

Seniors (60+) are the fastest growing segment of

society, with estimates of this population tripling by

2050 (United Nations, 2009; WHO, 2002). In

Canada, there are almost 5 million seniors, and it is

predicted that there will be an increase from 15% of

the population to 24.5% by 2041 (Statistics Canada,

2011). This growth will have an impact on

institutions, work places, culture and society, and

current roles may need to be reassessed (McDaniel

and Rozanova, 2011). With aging there can also be a

decline in physical and cognitive abilities, shift in

types of activities, change in social relationships and

support, and change in lifestyle (Kaufman, 2013).

Everyday living can become more difficult with

increased concerns, such as fractures, isolation,

physical ailments, and cognitive decline (WHO,

2002). There has been a recent interest in improving

quality of life and active aging in older adults

(Kaufman, 2013; WHO, 2002).

Quality of life in older adults has received

increasing attention among researchers (Bowling

and Dieppe, 2005; Lee, Lan, and Yen, 2011,

Sixsmith, Gibson, Orpwood, and Torrington, 2007).

A variety of terms have been used to describe

maintaining a good quality of life in older adults,

such as ‘successful aging’ and ‘active aging’.

Traditional views on successful aging have focused

on biomedical considerations (see Rowe and Kahn,

1997), but in recent years a more holistic approach

has been applied to concepts of aging. One survey

and review by Bowling and Dieppe (2005) found

that the most important dimensions which older

adults associated with successful aging were

psychological well-being, social well-being, and

physical health. The Institute of Aging also points to

the importance of holistic approaches that consider

psychological, social, environmental, as well as

biological dimensions of aging when planning

interventions designed to improve quality of life

(Joanette, 2013).

Recent research has shown that one of the main

areas that influence older adults’ quality of life is

their interactions with others and social support

(Adams, Leibbrandt, and Moon, 2011; Reichstadt,

Sengupta, Depp, Palinkas, and Jeste, 2010; Theurer

and Wister, 2010). Furthermore, social capital has

been found to have a specific relationship with the

perceived well-being of older Canadian adults

(Theurer and Whister, 2010). Social capital can

loosely be defined as the advantages and resources

available through an individual’s connections with

others (Cannuscio, Block and Kawachi, 2003).

These connections can involve various social

networks with different purposes (Litwin and

Shiovitz-Ezra, 2011).

276

Hausknecht S., Schell R., Zhang F. and Kaufman D..

Building Seniors’ Social Connections and Reducing Loneliness Through a Digital Game.

DOI: 10.5220/0005526802760284

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (AGEWELL-2015),

pages 276-284

ISBN: 978-989-758-102-1

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Technology is increasingly playing a role in

creating social connectedness (van Bel, Smolders,

IJsselsteijn, and de Kort, 2009). One technology that

has recently gained interest among researchers is

digital games and the possibilities they may afford.

Digital games provide an opportunity for individuals

to interact, communicate, and socialize in a fun way

(Kaufman, 2013). The opportunities they may afford

range from educational (Gee, 2003), cognitive

(Boot, Kramer, Simons, Fabiani, and Gratton, 2008),

social (De Schutter, 2011), psychological

(Rosenberg et al., 2010), physical (Wollersheim et

al, 2010), and let’s not forget having fun (Astell,

2013). Games can help to motivate older adults and

contribute to specific aspects of their lives that they

feel may improve their quality of life (Astell, 2013).

Digital games can provide an environment where

social interaction can occur in a fun and playful way.

In many of the discussions on designing digital

games to improve quality of life in older adults, both

socializing and interacting were found to be

important aspects (IJsselsteijn, Nap, de Kort, and

Poels 2007). A few studies have found that digital

games may provide an opportunity to increase social

connectedness and decrease loneliness (De Schutter,

2011; Kahlbaugh, Sperandio, Carlson, and Hauselt,

2011; Wollersheim et al, 2010). However, further

rigorous studies are required to understand the

possibilities in more depth.

Digital games can be used to offer older adults a

fun and playful context to improve social

connections. This in turn may help to improve

quality of life, well-being, health, and cognition. A

healthy happy population can benefit both seniors

and society. The promise of digital games for

developing and maintaining social connectedness

has been largely overlooked by research. There is a

need for experimental studies to determine whether

such theoretical promises can be realized. It is also

essential to examine the types of affordances that

games can provide for those playing them.

1.2 Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the Wii Bowling study was to

determine whether a digital game was effective in

enhancing various socio-emotional aspects such as

increasing social connectedness and decreasing

loneliness. A mixed methods was used to thoroughly

examine the experience.

This study will help to inform future studies that

may investigate the use of digital games as a way to

increase social connectedness, which may help to

increase quality of life in older adults.

1.3 Research Questions

1. Does playing a digital game increase social

connectedness?

2. Does playing a digital game decrease

loneliness?

3. What socio-emotional experiences do older

adults have while playing a Wii game for eight

weeks

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Social Connectedness and

Loneliness

No person is an isolated entity but interacts

throughout his/her life with numerous people in

different ways. These social connections can

influence a person’s trajectories throughout the life

span (Elder, 1994). Older adults interactions, social

connections and support are major contributors to

their quality of life and perceptions to aging

successfully (Adams et al., 2011; Reichstadt et al.,

2010; Theurer and Wister, 2010; Bowling and

Dieppe, 2005). A lack of social relationships can

affect older adults adversely in many ways (House,

Landis, and Umberson, 1988).

Social aspects of a person’s life can be examined

in a variety of ways, including social capital, social

connectedness, social network, and social support.

Social capital can be discussed as the benefits and

resources that become available through social

connections (Cannuscio et al., 2003). Social capital

may affect older adults’ perceptions of well-being

(Theurer and Wister, 2010). Additionally, social

capital is influenced by the various social networks

and connections, with those people having the most

diverse connections often showing the highest sense

of well-being (Litwin and Shiovitz-Ezra, 2011). This

may relate to the different types of socialization,

such as social support vs social connectedness. A

rich variety may help to fulfil numerous needs.

Social connections related to leisure and fun serving

their own role in the life course and future well-

being of older adults (Ashida andHeaney, 2008).

One contributor to social capital is a sense of

social connectedness. Social connectedness can be

defined as a person’s feelings of belonging and

being able to relate to others (van Bel et al., 2009).

Social connectedness can often also be related to

feelings of loneliness. If individuals feel a lack of

belonging and are not able to relate to others it is

BuildingSeniors'SocialConnectionsandReducingLonelinessThroughaDigitalGame

277

easier for them to become isolated (Cacioppo and

Patrick, 2008). Ashida and Heaney (2008) suggest

that social connectedness is separate from social

support and serves a different yet important role in

well-being. Social connectedness allows us the

enjoyment of others company and fulfills a social

need. Someone may provide support, but not the

sense of companionship (Ashida and Heaney, 2008).

Thus, Ashida and Heaney suggest that social support

and connectedness can be seen as two different

aspects fulfilling different needs.

Having a sense of social connectedness is

important not only for well-being but it also has an

impact on improved health measures (Ashida and

Heaney, 2008; Forsman, Nyqvist, Schierenbeck,

Gustafson, and Wahlbeck, 2012). For example, a

study by Forsman et al. (2012) showed that social

activities were effective in maintaining well-being

and a positive mental state, but also that social

contacts and relationships had positive outcomes for

health. Glei, Landau, Goldman, Chuang, Rodríguez

and Weinstein (2005) found that cognition was also

related to social engagement and network size. In

this study they examined the relationship between

cognition and social engagement. Participants who

took part in more social activities did better on

cognitive tests than those that had fewer or none.

Furthermore, it may be that social networks outside

the family have an increased effect on cognition,

compared to within the family (Glei et al., 2005).

Lack of social connectedness can also create

feeling of loneliness (Rook, 1990). Loneliness is

defined as a disturbing feeling someone gets when

they perceive that their social needs are not being

met by their current social relationships (Hawkley

and Cacioppo, 2010). It should be noted that this is a

perception, since people can be alone and not feel

lonely (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). Hawkley and

Cacioppo (2010) postulate that loneliness is similar

to social needs as pain is to physical needs. For

example, when we are hungry we experience hunger

and so when we feel we lack social connections we

become lonely. Thus, it is meant as a motivator for

searching for social connection.

Although there has been mixed results regarding

older adults and loneliness, a meta-analysis found

those over 80 were more likely to report increased

loneliness (Pinquart and Sorensvn, 2001).

Furthermore, a longitudinal study by Dykstra, van

Tilberg and de Jong Gierveld (2005) found that over

time many older adults increased their loneliness

scores. Furthermore, they found that increasing their

social network lowered feelings of loneliness.

Loneliness has also been connected to various

negative health and behaviour outcomes.

Social networks are considered the web of social

connections within an individual’s life (Ashida and

Heaney, 2008). These networks form the areas

where individual interact and connections with

others can occur (Ashida and Heaney, 2008).

Forming these networks can be a good starting point

to increasing a sense of social connectedness (van

Bel et al., 2009). This is the contextual basis for

where we can create feelings of social connectedness

(Ashida and Heaney, 2008). These networks extend

to numerous groups from family, neighbors, friends,

acquaintances, health care professions, and a number

of other people we come in contact with. Often the

more social ties a person has the more socially

connected they feel (Buckley and McCarthy, 2009).

Technology may be useful in developing social

connections. Baecker, Moffatt, and Massimi (2012)

suggest that technology may provide a medium

where entertainment, communication and social

connections can be enhanced. Of the technologies,

digital games can play an important role in

providing the motivation and excitement to pursue

aspects to improve older adult health, including

social well-being (Astell, 2013).

2.2 Digital Games and Older Adults

Digital games have potential for improving the lives

of older adults (Ijsselsteijn et al., 2007). They

provide a unique experience where through play a

participant may enhance certain areas depending on

the design. Thus, digital games are increasingly

being examined in ways that may be beneficial for

players.

Of the studies done on gaming for older adults

more reports are emerging about the possible

benefits (De Schutter, 2011; Ijsselsteijn, et al., 2007;

Kaufman, 2014; Kaufman, Sauvé, Renaud, and

Duplàa, 2014). Specific designs are being produced

for this demographic that allow for a variety of age

related adaptations and considerations (e.g.

Gamberini et al. 2006; Buiza et al. 2009). However,

empirical studies on older adults and digital game

use are still limited. Furthermore, older adults are

increasingly playing digital games on their own

accord. In 2011, the Entertainment Software

Association (ESA) (2011) reported that 29% of

computer game users are aged 50+. A previous

study that examined the beliefs of older adult gamers

found that they reported a variety of benefits,

including those related to socio-emotional aspects,

cognition, and learning (Kaufman et al, 2014).

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

278

Play within itself is often a social activity in

which interaction with others occurs (Vygotsky,

1978). Many games are specifically being designed

to incorporate social elements within them

(Ijsselsteijn, et al., 2007). Furthermore, various

digital games allow for specific types of interaction;

for example multiplayer online games allow for

players to interact within the games virtual space

while being at a distance, while console games allow

players to interact virtually and in person

simultaneously.

Wii games have been used in previous studies

with older adults and have shown some benefit (eg.

Wollersheim et al., 2010, Kahlbaugh et al., 2011).

Exergames, such as Wii Fit, have been used to

demonstrate the benefits of certain games for

improving balance and exercise in older adults

(Peng, Lin, and Crouse, 2011; Heick, Flewelling,

Blau, Geller, and Lynskey, 2012). These types of

games may also help with such areas as

rehabilitation and prevention (Wiemeyer and Kliem,

2012). Furthermore; as well as the possible physical

benefits they may also affect psychological health

(Wollersheim et al., 2010).

Many of these games allow for play with others,

either competitively or collaboratively, and may

provide a social medium. For example, Kahlbaugh et

al. (2011) performed a study with 35 older adults

assigned to either watching TV or playing Wii, and

they found the Wii group had a more positive mood

and lower levels of loneliness. In an intervention

study by Wollersheim et al (2010), it was found for

older individuals in a community dwelling asked to

play Wii together, that gameplay was reported by

participants as increasing their bonding with other

participants. Furthermore, gameplay has also been

reported to be useful in reducing feelings of

loneliness (De Schutter, 2011)

The possibility of digital games to increase social

interaction is not limited to the actual gameplay.

Discussing games within social networks has also

been shown to provide opportunities to exchange

information and have fun socializing (Pearce, 2008;

Nimrod, 2010). Nimrod (2010) found that older

adults used an online social website to satisfy their

need for play while fostering communication and

community.

Digital games have been used to improve various

aspects of quality of life for older adults; however,

many studies have focused on cognitive or physical

aspects and at this point only a few have examined

the social-emotional benefits.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

A Wii Bowling tournament was organized and took

place over two months. The Wii digital bowling

game was chosen because it allows for multiple

players and is fairly accessible to numerous age

groups. Furthermore, many older adults are familiar

with bowling. The tournament utilized both

collaboration (they worked in a team) and

competition (they competed against other teams).

The competitive aspect was increased by having

cash rewards for the first, second, and third teams.

3.1 Participants

Participants were older adults aged 65 and over.

There were a total of 73 participants who played in

the tournament from 14 different centres. The

participants either lived or frequently visited these

centres, including independent living centers, senior

recreation centers, and assisted living centers.

3.2 Recruitment and Data Collection

Seniors centres, retirement villages, and community

centres were approached to help recruit participants

and to provide a space. In total, 14 centres in the

Greater Vancouver area participated. Posters and

flyers were used to recruit participants with a date

for an information session where a researcher would

come to explain the study and tournament in detail.

3.3 Instrumentation

This study used a mixed methods approach using

both questionnaires and semi-structured interviews

to collect the data. This allowed for a triangulation

of the results, helping to confirm the findings while

also allowing us to dive deeper into the participants’

experience.

Firstly, there was a pre and post questionnaire

given to all participants. The following factors were

included: background/demographics such as age,

sex, living arrangements; levels of loneliness and

social isolation; and attitudes toward video games.

The questionnaire was adapted from the UCLA

Loneliness Scale (Russell, 1996) and the Overall

Social Connectedness Dimensions (van Bel et al.,

2009). Part of the adaption was a rewording to make

all the statement forms and response scales

consistent among the various questionnaires. A

group of researchers then tested each sentence for

understanding, and where there was confusion the

phrasing was altered for clarity. The response scale

BuildingSeniors'SocialConnectionsandReducingLonelinessThroughaDigitalGame

279

options were strongly disagree, disagree, unsure,

agree, and strongly agree. Respondents required 15-

20 minutes to complete the survey and received a

$20 honorarium for completing each questionnaire.

For 17 participants, a pre and post semi-

structured interview was conducted. The second

interview was an in-person interview based on semi-

structured questions that asked about the participants

perceptions of their game experience during the

tournament. This allowed the researchers to get a

more in-depth understanding of the participants’

experience with the game and the connections they

made during the tournament.

3.4 Data Analysis

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS 21.0.

Demographics were examined using frequencies and

percentages Paired sample t-tests were conducted

comparing pretest and posttest scores of loneliness

snd social connectedness.

The interviews were first transcribed and then

analyzed to find common codes. MaxQDA was used

to help with the coding. Codes were collected and

major themes were identified. Only those codes that

were present in at least 50% of the interviews were

examined for the overarching themes, one of which

was social connectedness

4 FINDINGS

Both the quantitative and qualitative findings are

reported below.

4.1 Participants’ Backgrounds

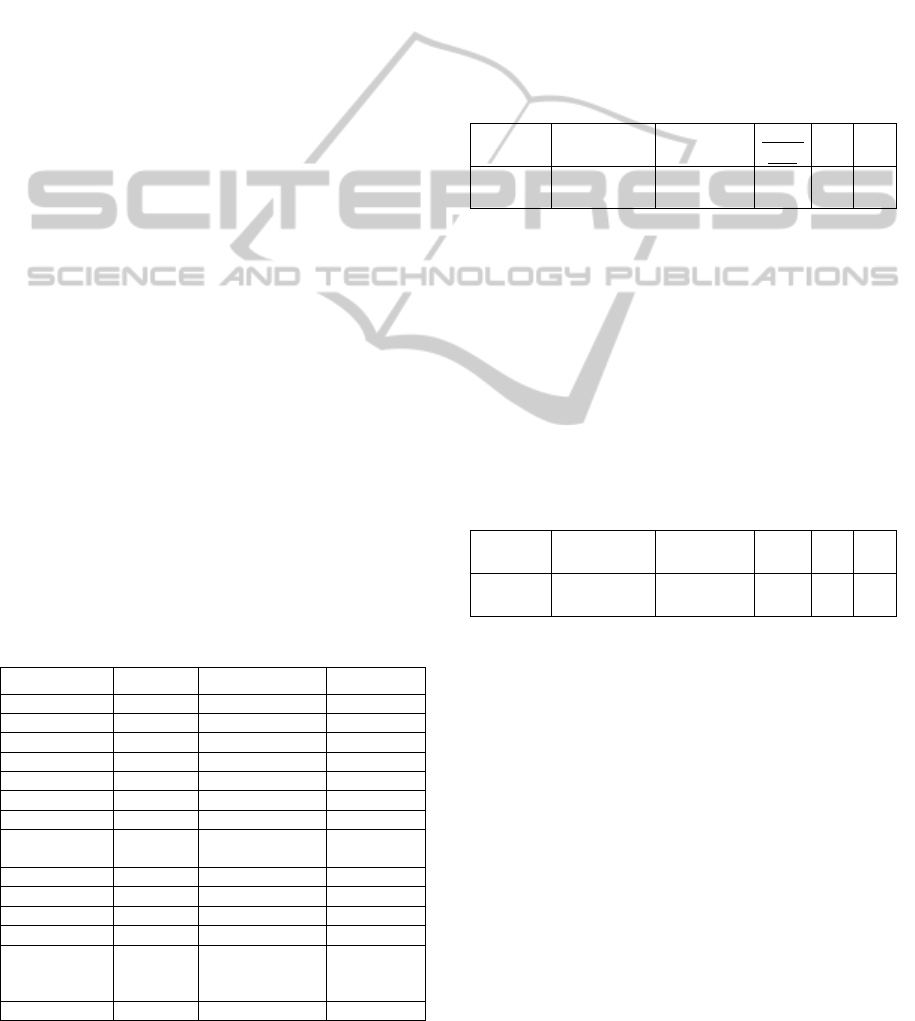

Table 1: Participant background characteristics.

Characteristics Category Frequency (N) Percent (%)

Sex Male 21 28.8

Female 52 71.2

Total 73 100

Age 65-74 21 28.8

75-84 27 37

85 + 25 34.2

Total 73 100

Living

arrangement

Alone 51 69.9

Other 22 30.1

Total 73 100

Housing House 7 9.6

Condo 29 39.7

Independent/

Assisted

living

37 50.7

Total 73 100

Table 1 summarizes participants’ background

characteristics. The participants consisted of a higher

portion of female participants (almost three quarters)

to males. The age of the participants was also

examined with a fairly even distribution between the

different categories. It is interesting as this included

a third of participants being 85 or over.

Approximately two-thirds lived alone versus only

one-third that lived with another person, and half

were in assisted or independent living conditions.

4.2 Social Connectedness

Table 2: Paired sample t-tests comparing pre-test and post-

test scores on social connectedness.

Group

Pre-test

Mean (SD)

Post-test

Mean (SD)

Effect

Size

t p

(N =73) 3.410 (0.53) 3.526 (0.48) 0.42 2.18 .033

A paired-samples t-test was conducted to

compare social connectedness before and after game

playing (Table 2). There was a significant difference

in the scores of social connectedness (M=3.410,

SD=0.528) before and (M=3.526, SD=0.485) after

game playing; t (72) =2.18, p = 0.033. The result

suggests that social connectedness score of older

adults increased after two month game playing.

4.3 Loneliness

Table 3 shows the results of a paired t-test tests comparing

pre-test and post-test score on loneliness.

Group

Pre-test

Mean (SD)

Post-test

Mean (SD)

Effect

Size

t p

(N=71) 2.214 (0.54) 2.049 (0.54) 0.42 3.63 .001

A paired-samples t-test was conducted to

compare loneliness before and after game playing

(Table 3). There was a difference in the score of

loneliness (M=2.214, SD=0.528) before game

playing and (M=2.049, SD=0.54) after game

playing; t (70) =3.518, p = 0.001. The result

suggests that loneliness score of older adults

decreased after two months of game playing.

4.4 Theme of Social Connectedness

Qualitative data analysis of the 17 interviews

revealed an overarching theme of increased social

connectedness through playing the Wii game. A list

of some of the top codes related to this and the

number of times they appeared are outlined in Table

4.

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

280

Table 4: Number of times and participants that a code was

found.

Code

No. of times

applied

No. of

people

Interaction with others b/c of Wii 84 16

Better social connections 70 13

Conversations about Wii with

family and friends

49 13

Social-connectedness was a major theme that

occurred within the interviews of participants. This

was found to have three main categories: increased

social interactions around playing Wii Bowling,

stronger social connections with previous

acquaintances, playful conversations with family

and friends.

4.4.1 Increased Social Interaction around

Playing Wii Bowling

During the interviews many participants (16)

commented about the social opportunities that

playing the game afforded. It seemed to give some

participants a break and a fun way to interact with

others. For example, John reported that, “I would

say my spirits have been uplifted a bit. Definitely,

and it’s because of this activity. Because up to that

point in time, I just do my thing and go about my

daily business, so to speak. But this, again, brought

us together and very beneficial.”

Some of the interactions continued outside of the

game. For example one participant, Liz, points out

“Well, I got to know the lady next door. And

because she was on my team, and we found out that

we lived next door to each other. So we are going to

share a garden spot together. Um, and now that I

look at the size of the spot, we probably both needed

one. But anyway, we will garden together. We’re

going to buy the plants together. So, yes, I met my

neighbour. So that was—and I might not have spent

the time with her otherwise.”

These interactions were not limited to the players

but also other older adults who came to watch the

team play, as pointed out by Faith “Because we had

people come to watch. Because they showed

interest, they thought "what are they up to now".”

The Wii game allowed for participants and

observers to increase their daily interaction with

others. This allowed players to meet new people

within the centres. As Bill explained “It’s expanded

the socializing in this complex, and I think that was

really helpful, especially for the new people.”

4.4.2 Stronger Social Connections Formed

Playing the game didn’t just increase the amount of

interaction but also allowed players to get to know

each other better and build stronger connections. As

Jocelyn explains, it helped her to bond with some of

the people she had only ever said hi to:

“It got me mixing or getting—I knew two of the

girls I was playing with—I knew them quite well,

but I met somebody else that I just sort of said hello

to in the building. So we got together. And we’ve

kind of bonded quite nicely and there’s been people

come up to watch and, you know, and you do more

than just saying hello like you say in the elevator.

“Hello,” and that’s as far as it gets. Then, they’ll

come up and they’ll watch or they’ll sort of like

encourage them to kind of try it. So there’s a lot of

communication. I really enjoyed it. “

Many of the participants stated that they got to

know the other team members better as Faith stated

“We got to know our team members well, and we

had a good time.” Some of these bonds extended to

outside of the game as mentioned by another

participant “I became better acquainted with several

of the residents. And we exchanged contact

information.”

Stronger connections to people who were

previously acquaintances were sometimes formed.

As Ruby explained, “…when we pass each other

now, we always stop and have a chat. They’re

different girls than I’m used to and so it sort of

added to my collection of girls. (laughing).” For

Isabelle this opportunity to get to know people and

get together with them on a regular basis was

important to belonging. She stated, “you get to

associate with people you probably wouldn’t

normally associate with all the time, and it gives you

a sense of belonging, right.”

The playful environment fostered many of these

social connections as Ruby states “the fact that you

mix together and have a few laughs and enjoy each

other. It's good for you too, to be doing something

rather than sitting in your room.”

4.4.3 Playful Conversations with Family and

Friends

Outside of the Wii Bowling tournament and building

networks participants also spent a certain amount of

time discussing the game with family and friends. It

was something fun to talk about. A few participants

mentioned how it became a point of conversation

and activity with grandchildren, such as John who

said, “when I pick up my grandson or my

BuildingSeniors'SocialConnectionsandReducingLonelinessThroughaDigitalGame

281

granddaughter, after school, they’ve got a Wii

machine and I practice my golf – pick up my golf

again. And tennis. And I said, “Now, it’s grandpa’s

turn” my grandson, Jacob: “Come here, because

Grandpa’s going to whip your butt.” (Laughs).”

Another participant, Jane, mentioned how her

family cheered her on, “They loved it! They were so

proud of me. I played with my grandsons and I

always beat them. They rooted for me! They adored

it.”

Even the older players found that their families

were often interested, as this 90-year-old player

expressed:

“They laughed at first. I was thinking why not

but they started to get interested and wanted to know

how I was doing. Did I still enjoy it and all this? I

told them we did, ‘cause we were having fun

together. They thought that was good.”

Another participant expressed how the

excitement she had for the game caused her to talk

to others about it, “and I’ve been talking to

everybody about it, you know, my friends and my

family. Yeah. I was just so excited that I joined.”

One of the winners of the tournament, Margot,

explained when she “phoned my family to tell them

we had won, you would have thought that they had

won. I had the granddaughter: “Wow, Granny!””

As can be seen by these few examples,

participants did not just attend the games and then

forget about them. Instead they discussed it outside

of the tournament. These playful conversations and

activities with various age groups may help to

enhance intergenerational relationships and increase

social connections through not simply the game, but

through the conversational aspects it seemed to

inspire in the participants.

5 DISCUSSION

In this mixed methods study, both the quantitative

and qualitative analysis showed an increase in socio-

emotional benefits for older adults who played Wii

Bowling, particularly in relation to social-

connectedness. The group increased their scores in

social connectedness and decreased loneliness scores

from pre to post test. Social connectedness was

defined as the sense of belonging and being related

to others (van Bel et al., 2009). The quantititave

questionnaire adapted from van Bel et al. (2009) was

used and confirmed a change in these scores. The

results were further confirmed and expanded upon

through the qualitative findings, in which most of

the participants interviewed found that the game

increased their social connections in some way.

Social connectedness and loneliness are

intimately related since feelings of not having a

social connection can result in feelings of loneliness

(Rook, 1990). This study seems to reinforce this

idea, as both scores were affected. Furthermore, the

types of bonds and connections go beyond that of

game play. Previous research found that individuals

with diverse social connections and networks show

the highest sense of well-being (Litwin and Shiovitz-

Ezra, 2011). Although most of the interaction

occurred during the Wii Bowling event, it seemed to

extend to various other connections such as with

family, friends, or the team members in different

circumstances. All of which may increase the

participants social capital. Many of the connections

formed and described were related to companionship

versus support. It has been noted that companionship

plays an important role in meeting the social needs

of older adults (Ashida and Heaney, 2008). These

are particularly important when considered with

loneliness. In that, a simple feeling of belonging

may help to reduce loneliness (Rook, 1990).

It should be noted that the current study was

designed with a variety of social considerations that

may have helped to enhance the social experience. It

utilized both competition and collaboration, since

members collaborated in a team but also competed

with other teams. Spectators were also encouraged

to watch and cheer the participants on. This could

help make the environment a socially rich context.

The study did not examine the effect of the Wii

Bowling tournament on the observers. However, this

would be an interesting aspect to examine in future

studies.

The study also had a large number of participants

over eighty-five and this may help to promote

further research into the possible benefits of digital

games for this age group. Further studies could

examine ways to help support interaction and make

games as accessible as possible for different

generations. Finally, it would be of interest to

examine whether digital games have a similar

benefit if played online with others. Thus, whether

the physical presence is necessary or whether older

adults gain a sense of social connection even if

interacting through a virtual environment.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests that through games where older

adult players play together it allows them to increase

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

282

their sense of belonging and reduce loneliness.

Digital games are a fun way for older adults to

interact and form more social networks, or tighten

the bonds of those already formed. These increases

in social connectedness may contribute to an

increased quality of life. Increasing quality of life of

older adults through means of an engaging leisure

activity could be important to those experiencing

feelings of isolation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank the Social Sciences and

Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC)

for their financial support of this project.

REFERENCES

Adams, K. B., Leibbrandt, S., and Moon, H. (2011). A

critical review of the literature on social and leisure

activity and wellbeing in later life. Ageing and Society,

31(4), 683-712.

Ashida, S., and Heaney, C. A. (2008). Differential

associations of social support and social connectedness

with structural features of social networks and the

health status of older adults. Journal of Aging and

Health, 20(7), 872-893.

Astell, A. (2013). Technology and fun for a happy old age.

Technologies for Active Aging-International

Perspectives on Aging, 9, 169-187.

Baecker, R., Moffatt, K., and Massimi, M. (2012).

Technologies for aging gracefully. Interactions, 19(3),

32-36.

Boot, W. R., Kramer, A. F., Simons, D. J., Fabiani, M.,

and Gratton, G. (2008). The effects of video game

playing on attention, memory, and executive control.

Acta Psychologica, 129(3), 387-398.

Bowling, A., and Dieppe, P. (2005). What is successful

ageing and who should define it? BMJ: British

Medical Journal, 331(7531), 1548-1551.

Buckley, C., and McCarthy, G. (2009). An exploration of

social connectedness as perceived by older adults in a

long-term care setting in Ireland. Geriatric Nursing,

30(6), 390-396.

Buiza, C., Soldatos, J., Petsatodis, T., Geven, A., Etxaniz,

A., and Tscheligi, M. (2009). HERMES: Pervasive

computing and cognitive training for ageing well. In S.

Omatu et al. (Eds.), IWANN '09 Proceedings of the

10th International Work-Conference on Artificial

Neural Networks, Part II: Distributed Computing,

Artificial Intelligence, Bioinformatics, Soft Computing,

and Ambient Assisted Living (pp.756-763). Berlin:

Springer-Verlag.

Cacioppo, J. T., and Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness:

Human nature and the need for social connection.

New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Company.

Cannuscio, C., Block, J., and Kawachi, I. (2003). Social

capital and successful aging: The role of senior

housing. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139(5_Part_2),

395-399.

De Schutter, B. (2011). Never too old to play: The appeal

of digital games to an older audience. Games and

Culture, 6(2), 155-170.

Dykstra, P. A., van Tilburg, T. G., and de Jong Gierveld,

J. (2005). Changes in older adult loneliness results

from a seven-year longitudinal study. Research on

Aging, 27(6), 725-747.

Elder, G. H. Jr. (1994). Time, human agency, and social

change: Perspectives on the life course. Social

Psychology Quarterly, 57(1), 4-15.

Entertainment Software Association (ESA) (2011). ESA

2011 ‘Essential Facts’ note rise in women, adult

gamers. Retrieved from http://www.joystiq.com/

2011/06/08/esa-2011-essential-facts-note-rise-in-

women-adult-gamers/

Forsman, A. K., Nyqvist, F., Schierenbeck, I., Gustafson,

Y., and Wahlbeck, K. (2012). Structural and cognitive

social capital and depression among older adults in

two Nordic regions. Aging and Mental Health, 16(6).

771-779.

Gamberini, L., Alcaniz, M., Barresi, G., Fabregat, M.,

Ibanez, F., and Prontu, L. (2006). Cognition,

technology and games for the elderly: An introduction

to ELDERGAMES Project. PsychNology Journal,

4(3), 285-308.

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us

about learning and literacy. New York: Palgrave

Macmillan.

Glei, D. A., Landau, D. A., Goldman, N., Chuang, Y. L.,

Rodríguez, G., Weinstein, M. (2005). Participating in

social activities helps preserve cognitive function: an

analysis of a longitudinal, population-based study of

the elderly. International Journal of Epidemiology,

34(4), 864-871.

Hawkley, L. C., and Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness

matters: A theoretical and empirical review of

consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral

Medicine, 40(2), 218-227.

Heick, J. D., Flewelling, S., Blau, R., Geller, J., and

Lynskey, J. V. (2012). Wii Fit and balance: Does the

Wii Fit improve balance in community-dwelling older

adults? Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 28(3), 217-

222.

House, J. S., Landis, K. R., and Umberson, D. (1988).

Social relationships and health. Science, 241(4865),

540-545.

IJsselsteijn, W., Nap, H. H., de Kort, Y., and Poels, K.

(2007). Digital game design for elderly users. In B.

Kapralos, M. Katchabaw, and J. Rajnovich (Eds.),

Proceedings of the 2007 Conference on Future Play

(pp. 17-22). New York, NY: ACM.

Joanette, Y. (2013). Living longer, living better: Preview

of CIHR Institute of Aging 2013-2018 strategic plan.

BuildingSeniors'SocialConnectionsandReducingLonelinessThroughaDigitalGame

283

Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne

Du Vieillissement, 32(2), 209-213.

Kahlbaugh, P. E., Sperandio, A. J., Carlson, A. L., and

Hauselt, J. (2011). Effects of playing Wii on well-

being in the elderly: Physical activity, loneliness, and

mood. Activities, Adaptation and Aging, 35(4), 331-

344.

Kaufman, D., (2013, October) Aging well: Can digital

games help? Overview of the project. Paper presented

at the World Social Science Forum 2013, Montreal,

QC.

Kaufman, D. (2014). Socio-emotional benefits of digital

games for older adults. In Proceedings, 6

th

International Conference on Computer Supported

Education (CSEDU 2014), Barcelona, Spain. Setubal,

Portugal: SciTePress Digital Library Online.

Kaufman D., Sauvé, L., Renaud, L, and Duplàa, E. (2014).

Cognitive benefits of digital games for older adults. In

J. Herrington, J. Viteli, and M. Leikomaa (Eds.),

Proceedings of the World Conference on Educational

Media and Technology (EdMedia) 2014 (pp. 289-

297). Waynesville, NC: Association for the

Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Lee, P.-L., Lan, W., and Yen, T.-W. (2011). Aging

successfully: A four-factor model. Educational

Gerontology, 37(3), 210-227.

Litwin, H., and Shiovitz-Ezra, S. (2011). Social network

type and subjective well-being in a national sample of

older Americans. The Gerontologist, 51(3), 379-388.

McDaniel, S. A., and Rozanova, J. (2011). Canada’s aging

population (1986) redux. Canadian Journal on Aging,

30(3), 511-521.

Nimrod, G. (2010). Older adults’ online communities: A

qualitative analysis. Gerontologist, 50(3), 382-392.

Pearce, C. 2008. The truth about baby boomer gamers - A

study of over-forty computer game players. Games

and Culture, 3(2), 142-174.

Peng, W., Lin, J., and Crouse, J. (2011). Is playing

exergames really exercising? A meta-analysis of

energy expenditure in active video games.

Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking,

14(11), 681-688.

Pinquart, M., and Sorensen, S. (2001). Influences on

loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic and

Applied Social Psychology, 23(4), 245-266.

Reichstadt, J., Sengupta, G., Depp, C., Palinkas, L. A., and

Jeste, D. V. (2010). Older adults’ perspectives on

successful aging: Qualitative interviews. American

Journal for Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(7), 567-575.

Rook, K. S. (1990). Social relationships as a source of

companionship: Implications for olderadults’

psychological well-being. In B. R. Sarason, I. G.

Sarason, and R. P. Gregory (Eds.), Social support: An

interactional view (pp. 219-250). New York: John

Wiley.

Rosenberg, D., Depp, C. A., Vahia, I. V., Reichstadt, J.,

Palmer, B. W., Kerr, J., Jeste, D. P. (2010). Exergames

for subsyndromal depression in older adults: A pilot

study of a novel intervention. The American Journal of

Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(3), 221-226.

Rowe, J. W., and Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging.

Gerontologist, 37(4), 433-440.

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version

3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal

of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20-40.

Sixsmith, A., Gibson, G., Orpwood, R., and Torrington, J.

(2007). Developing a technology ‘wish list’ to enhance

the quality of life of people with dementia.

Gerontechnology, 6(1), 2-19.

Statistics Canada. (2011). The Canadian population in

2011: Age and sex. Ottawa, Ontario: Statistics Canada.

Retrieved on October 2, 2013 from

http://www12.statcan.ca/censusrecensement/2011/as-

sa/98-311-x/98-311-x2011001-eng.cfm.

Theurer, K., and Wister, A. (2010). Altruistic behaviour

and social capital as predictors of well-being among

older Canadians. Ageing and Society, 30(1), 157.

United Nations (2009) World Population Aging. Retrieved

August 24, 2012 from http://www.un.org/esa/

population/publications/WPA2009/WPA2009_Workin

gPaper.pdf.

van Bel, D. T., Smolders, K. C. H. J., IJsselsteijn, W. A.,

and de Kort, Y. (2009, January). Social connectedness:

Concept and measurement. In Intelligent

Environments 2009: Proceedings of the 5th

International Conference on Intelligent Environments,

Barcelona, Spain 2009 (pp. 67-74).

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Wiemeyer, J., and Kliem, A. (2012). Serious games in

prevention and rehabilitation—a new panacea for

elderly people? European Review of Aging and

Physical Activity, 9(1), 41-50.

Wollersheim, D., Merkes, M., Shields, N., Liamputtong,

P., Wallis, L., Reynolds, F., and Koh, L. (2010).

Physical and psychosocial effects of Wii video game

use among older women. International Journal of

Emerging Technologies and Society, 8(2), 85-98.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2002). Active aging:

A policy framework. Geneva: World Health

Organization. Retrieved September 1, 2014 from

http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2002/WHO_NMH_NPH_

02.8.pdf.

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

284