Assessing and Implementing English-learning Mobile Applications

in a University Graduation Program: SLA 2.0

Artur André Martinez Campos

1

and João Correia de Freitas

2

1

Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Rua Francisco Foreiro 23, Lisboa, Portugal

2

Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Monte da Caparica, Lisboa, Portugal

1 RESEARCH PROBLEM

Our research problem for this doctoral proposal is

verifying the efficacy of using tablets and

smartphones Learning Virtual Environment (LVE)

applications designed for the English language

autonomous learning and if these apps can be

implemented as mandatory in an English university

graduation course syllabus.

The research question comes from the fact that

most students enrolled at this course at the university

where I work (UNIT – Brazil) and where I develop

my doctoral studies (UNL – Portugal) are digital

natives and competent users of the aforementioned

gadgets in a daily basis.

2 OUTLINE OF OBJECTIVES

The major objectives for this doctoral research are:

To verify the efficacy of using (two) tablet and

smartphone Virtual Learning Environments

named Busuu (01) and Babbel (02) for the

Second Language Acquisition of the English

idiom in an autonomous and self-paced way

using as a focus group 50 UNIT and 50 UNL

students.

To assess all pedagogical resources presented

by those apps and their HCI (Human Computer

Interaction) with criteria such as Immediate

Feedback, Information Density, User Control,

Consistency and Compatibility, then

establishing an academic perspective to the

applications.

To implement ONE of the aforementioned

Virtual Learning Environment applications into

the English Language graduation course

syllabus at Universidade Tiradentes (Brazil)

because most students enrolled at this higher

education institution are digital natives and

tablets and smartphones users.

3 STATE OF THE ART

The presence of smartphones and tablets has

broadened the possibility of learning a foreign

language and apps focused on SLA are used by

many university graduates around the world

nowadays. As an Assistant Professor of English

Language and Literature at UNIT, I am trying to

implement the use of ICT on a daily basis through

the suggestion of installing digital dictionaries

(Farlex, dictionary.com) and thesaurus apps

(Advanced English) on their personal phones. After

that implementation, the results in class performance

improved a lot; especially concerning their new

vocabulary acquisition (Krashen, 1981) and

determination to learn (Papert, 1996).

It has to be mentioned that the familiarity with

this new “interaction design” (Banga & Weinhold,

2014) for searching unfamiliar vocabulary proved to

be more comfortable to them than a printed

dictionary. As a next step after this experience, I

realized that apps such as Busuu and Babbel were

worth a deeper and longer analysis. In charge of

these curricular units at UNIT and with the project

idea of implementing a Mobile/Tablet Application

as part of the syllabus (Slattery, 2006), I decided to

investigate some of the authors dealing with mobile

learning or m-learning (Anderson, 2008; Chen,

2013; Kukulska-Hulme (2009); Vavoula, 2005) and

its associated consequences and understand which

concepts would fit best to my study.

Bringing one of the understandings of m-

learning to this study, we are certain that our

students’ use of such apps “happens anywhere, in

special outside of class, it is focused on the student

(learner-centered) and it is thoroughly ubiquitous

(Valk, Rashid and Elder, 2010). These authors

clearly depict the reality we are soaring with this

thesis project. Personally, I have received online

comments from students outside class hours which

indicate they were into a “SLA mode” at that

particular moment and sending me a WhatsApp

8

André Martinez Campos A. and Correia de Freitas J..

Assessing and Implementing English-learning Mobile Applications in a University Graduation Program: SLA 2.0.

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

message or an Inbox on Facebook certainly showed

a commitment to their L2 autonomous learning

process (Chen, 2013). This organic presence of

Learning Virtual Environment applications in our

smartphones is a new paradigm (Murray, 2011) in

instruction; now the “school” is inside our pockets

and the access to any information, website or

application has really catapulted the accessibility to

knowledge to a unique pattern.

Hence, we believe that this new horizon in

language instruction (Kukulska-Hulme, 2009) will

enhance and broaden the capacities of SLA. When

analyzing the spatial or location characteristic of

education; tablets and smartphones are promoting

learning beyond classroom walls which according to

Vavoula (2005) is

“any sort of learning that happens when the learner is

not at a fixed predetermined location, or learning that

happens when the learner takes advantage of the

learning opportunity offered by mobile technologies

has to be defined as m-learning”. (Vavoula, 2005)

Classrooms walls are long gone with this uber-

access to smartphones and tablets and it is more than

adapting to a new learning process for schools and

higher education institutions (Papert, 1996), it is a

complete redesign of educational notions (Blake,

2008) that both must embark due to these recently

created learning environments. Another issue to be

observed here is the narrowing of the gap between

Formal and Informal learning environments (Bo-

Kristensen, Ankerstjerne, Neutzsky-Wulff and

Schelde, 2009) in a moment when most fossilized

ideas about Pedagogy and Education as a whole are

under scrutiny. Moreover, the blurry line between ‘i-

am-studying” versus “i-am-not studying” traced on

young adults and teens minds when it is about

school or learning is being erased (Robinson, 2006).

The informality, easy accessibility and ubiquitous

presence (Leu et al, 2004) may take the formal

school-interface out of perspective.

On this research proposal, we also shed some

light over the urgent necessity of developing some

new approaches to educational techniques at the

XXI century university classrooms due to the fact

that we have seen a lack of interest by some students

in traditional instruction methodologies; result of the

distance between their multi-faceted reality

involving electronic and face-to-face

communications versus the lecturer style of

teaching. According to Oblinger (2005),

“New ways of teaching and learning have to be

employed in an attempt to ensure these technologies

are used to their fullest extent to engage all learners

and to enable the construction of culturally significant

meaning for Net Generation students. We are finding

that new pedagogies are facilitating the engagement of

other students for whom the strategies and learning

environment is conducive to engaged and deep

learning”. (Oblinger, 2005)

The Net Generation (Tapscott, 1998) might be

taken as a broad concept nowadays and we must put

into perspective that technology has overpowered

people of all ages and walks of life. Consequently,

including this new perspective of apps into the

English language learning provided by UNIT classes

may deploy the institution at the forefront of

T.A.L.L. users in Northeast Brazil and, we believe,

this is unprecedented in any higher education

institution in Sergipe.

Learning a foreign language in an online

community reinforces L2 as we could see in Lan et

al (2007) who asserts that “language learning is no

longer limited to one-way individual learning, but

can be expanded to a two-or multi-way collaborative

learning”. As a Professor at the English Department,

I stated my scientific problem as being the

responsible for the implementation of m-learning to

the English Graduation course syllabus during the 1

st

and 2

nd

semesters of it. There is an understanding

that this new pedagogical procedure will prepare

“future teachers of the idiom to the reality of their

audience in post-modern educational times”

(Campos, 2008).

As mentioned earlier, the majority of the

university students we have in our classrooms

nowadays are digital natives (Prensky, 2001) and

according to this author, the reality is that,

“Today’s average college grads have spent less than

5,000 hours of their lives reading, but over 10,000

hours playing video games (not to mention 20,000

hours watching TV). Computer games, email, the

Internet, cell phones and instant messaging are

integral parts of their lives.” (Prensky, 2001)

In our English Department, we are preparing

educators for a different language teaching and

learning perspectives as they will be the teachers of

the kids in high schools today who use computers,

tablets and smartphones in a more organic model

(Downes, 2012) way than their instructors. About

the theory for Linguistics, the students will perform

the Second Language Acquisition mostly based on

the principles of Krashen’s (1981) language

acquisition theory of i+1, being i – the background

knowledge and +1, the new knowledge. They will

also make use of Vygostky’s (2002) Zone of

Proximal Development as well as Thorne and

Payne’s (2005) use of podcasts theory here.

Green and Hannon (2007) also share some ideas

AssessingandImplementingEnglish-learningMobileApplicationsinaUniversityGraduationProgram:SLA2.0

9

into the necessity of a new horizon in teaching as

“children and young adults are establishing a

relationship to knowledge gathering nowadays

which is alien to their parents and teachers”. This

knowledge has been gathered by surfing a multitude

of platforms that bring access to information through

a perspective made of audio, texts, videos, chats,

photos and hyperlinks altogether (Papert, 1996).

They learn everywhere (Anderson, 2008) and in a

new dimension through these electronic gadgets. If

we bring into this reality the application of VLE

language apps as a routine, L2 learning may be

rewarded. As some studies dealing with the use of

apps in Asia are showing, “it was concluded that the

combination of formal and informal learning fosters

contextualized learning, productive outputs, and a

socio-constructivist acquisition of the target

language.” (Chen, 2013). Our target in this doctoral

research is to verify the length of this concept when

you implement tablets/smartphones apps aimed at

L2 acquisition in a university course syllabus

planned to language learning.

On this attempt of implementing an app as a

mandatory content for a university degree, I have to

analyse their HCI with an academic and thorough

schema and therefore we are using some elements of

the ergonomic criteria of Bastien and Scapin (2003)

defined as Immediate Feedback, Information

Density, User Control, Consistency and

Compatibility. We are also investigating how these

apps define language progression, how the

vocabulary, themes, dialogues evolve and finally,

the “schooling” approach that is aimed on language

learning that these tablet and smartphones’ versions

bring. The future implementation to the course

syllabus takes into account the approach of learning

needs that focus on Proficiency by Nation (2010)

associated with the ideas of assessing needs in a

framework for a course development from Graves

(2000) and the reconceptualization tendencies seen

in Slattery (2006).

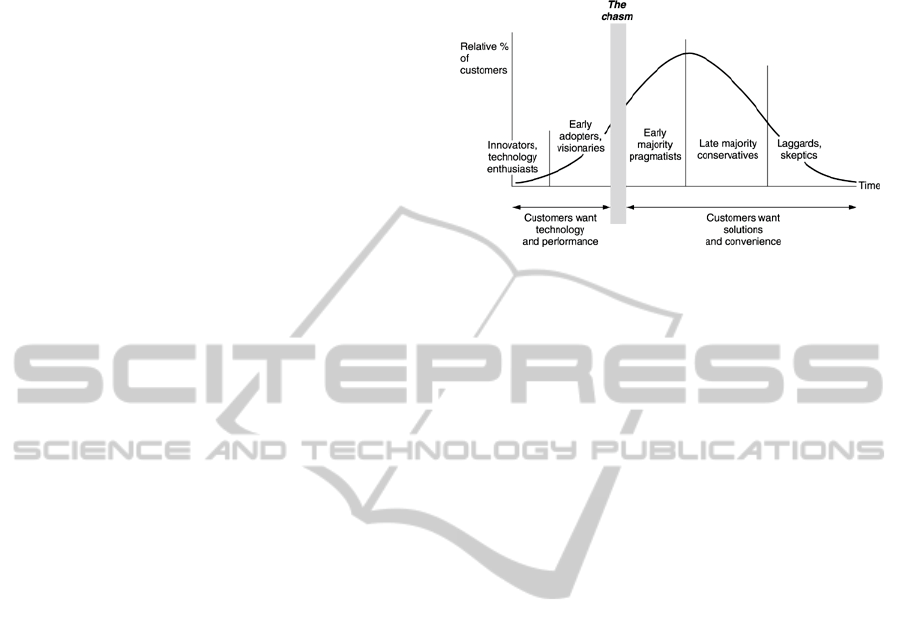

I also have to take into full perspective Rogers’

Diffusion of Innovations theory seen here through

the Technology Adopter Category Index (TACI).

Rogers (2003) apud Sahin (2006) establishes that

innovations and, in special Technology, follows a

procedure of being adopted by people according to

attributes such as Relative Advantage,

Compatibility, and Observability among others. The

pace of adoption takes a length of time that varies in

relation to the adopters which are labeled as

Innovators (2.5%), Early adopters (13,5%) Early

majority (34%), Late majority (34%) and Laggards

(16 %). We also include Dugas (2005) flexibility

perception to T.A.C.I.. The Figure 1 exemplifies

how these rates are distributed through time.

Figure 1: T.A.C.I. – Technology Adopter Category Index.

4 METHODOLOGY

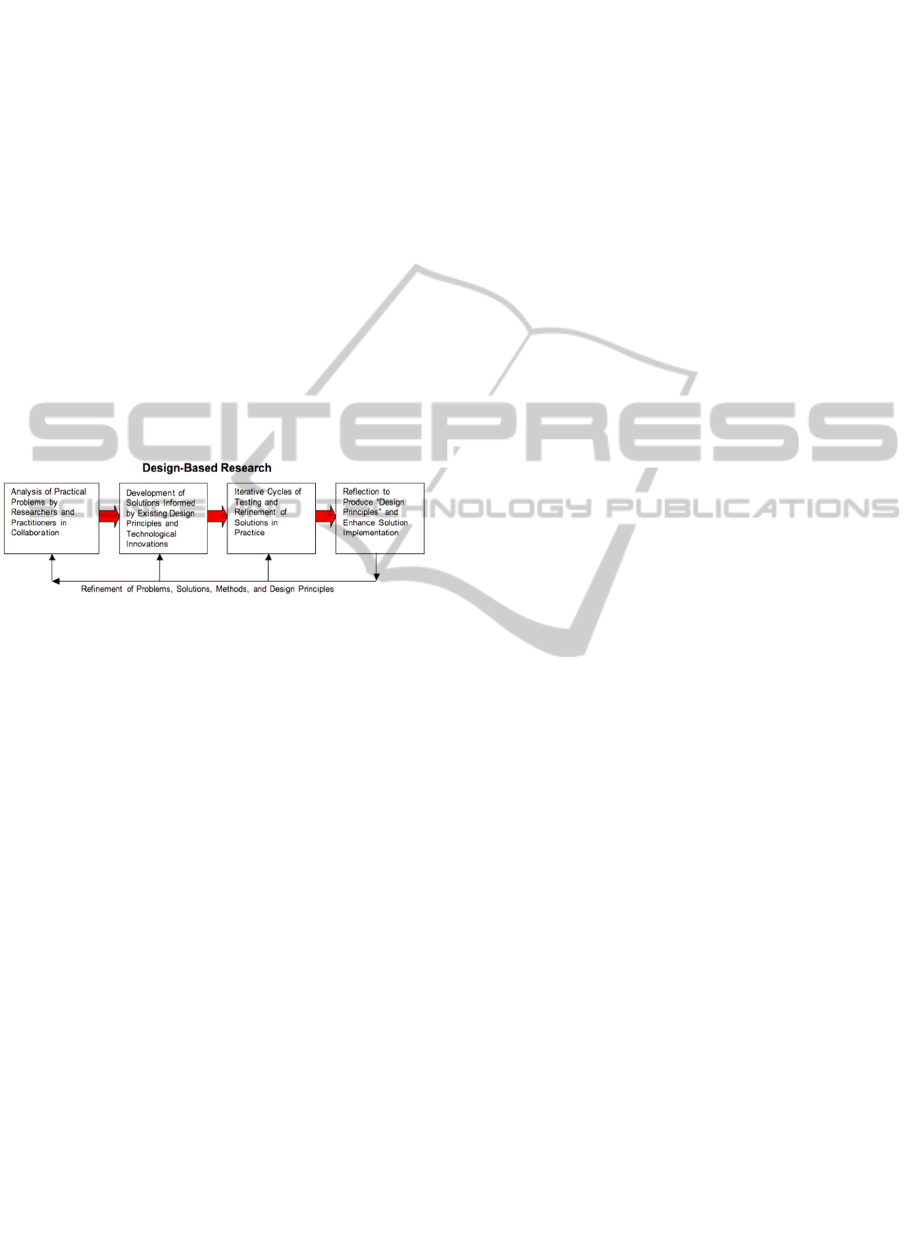

As a methodological approach to this project,

focused on the implementation of a new paradigm in

instruction and pedagogical studies – learning

through mobile apps – my Advisor (Prof. Dr. João

Correia de Freitas) suggested performing a Design-

Based Research (DBR) due to the essence of our

doctoral research dwelling with the empirical nature

of this unorthodox way of learning. Adopting new

learning methods in a teaching environment is not an

easy task, hence we use here the concepts of

Herrington (2007) and Barab and Squire (2004)

since we are “producing new theories, artifacts, and

practices that account for and potentially impact

learning and teaching in naturalistic settings”.

Checking other authors who suggest performing

a Qualitative Research as a Design Based Research,

it is mandatory to consider van den Akker,

Gravemeijer, McKenney and Nieveen (2006) who

specify that “design-based research holds great

promise for enhancing both the theoretical

contributions and public value of educational

technology research.” Nevertheless, we have to pay

attention to the fact that DBR is a work-in-progress

and we cannot forget the ways the research goes

through and the reasons for its existence. As

Herrington (2007) puts it “…typically the research

has sought to demonstrate the achievement gains of

technology – facilitated learning over conventional

methods of teaching with little regard for an

understanding of how or why the gains might have

been realized.”

Looking further into authors that contributed to

the definition of DBR when developing qualitative

investigations in technology and education, we bring

the ideas of the pioneer Collins (1992) who

CSEDU2015-DoctoralConsortium

10

acknowledges that this methodology addresses the

complexity of the problems in real classroom

context when

“integrating known and hypothetical design principles

with technological affordances to render plausible

solutions to these complex problems and conducting

rigorous and reflective inquiry to test and refine

innovative learning environments as well as to define

new design principles.” (Collins, 1992)

To Herrington (2007), “a research proposal for a

doctoral study using a design-based approach must

include a practitioner-oriented focus as well as

degrees of collaboration that are not necessarily

required for more traditional predictive research

designs”. Another author, Reeves (2006), divided a

DBR in 4 main steps (Analysis of Problems >

Development of Solutions > Iterative Cycles of

Testing > Reflection to enhance Solutions) as seen

on Figure 2.

Figure 2: 4 Steps to a Design-Based Research.

It is also a fact that through this methodology,

the research comprises a strong connection between

researcher and students that is “derived from the

definition of the research problem in close

collaboration with practitioners, and fine tuned

through literature that serves to (a) help flesh out

what is already known about the problem and (b) to

guide the development of potential solutions

(Herrington, 2007).” We sum up the methodological

approach with the conceptual idea of Barab and

Squire (2004) reflected in the affirmation that a

“design-based research suggests a pragmatic

philosophical underpinning, one in which the value

of a theory lies in its ability to produce changes in

the world.”

After these four steps of DBR in our

methodological procedures, after the collection of

data through questionnaires, interviews and

performance tests to be applied to the 100 subjects

(50 at UNIT and 50 at UNL) involved at this study

and its thorough analysis to verify the efficacy of

those apps in language progression; we may

probably take this doctoral research to its final part –

the choice of the (most adequate) application for the

Implementation at the Graduation course. As said

before, this research project aims at assessing which

app represents a better platform to learning a L2

through T.A.L.L. or M.A.L.L and we had to take

into our prism the ideas of an evaluative research

whose qualitative data collection will be made

through the use of the applications by the students.

An evaluative study starts with the assumption that

the research topic must be understood “holistically”

(McKay, 2006).

This is done by assessing a variety of factors that

might affect the final result. As we understood from

our references, “the main goal of the evaluation

report is to inform and/or influence decision makers

and the relative emphasis of the two activities must

be different” (Jamieson, 1984). Summing up, the

evaluative research to be performed here will

promote an analysis of both apps in a simulation of

studies taking all the pedagogical steps proposed by

the aforementioned applications.

4.1 Data Collection and Analysis

After the installation and use of the applications

Busuu and Babbel by the purposeful chosen 100

subjects for six months, we will perform a series of

questionnaires, semi-structured interviews,

observations and oral conversations that will record

this information on protocols designed to organize

what was granted by the participants. This

Qualitative data will be explored, coded, described

in themes and segmented (Creswell, 2012). After

that, we will summarize the findings and compare

them to the literature. Of course, we bear in mind

that this qualitative research has to validate the

accuracy of the findings through the linguistic

progression of the subjects, bringing or not the

concept of Efficacy to the use of apps.

5 APPLICATIONS OVERVIEW

5.1 Busuu

The initial screen brings the registration, selection of

language, then your level and courses. Through the

selection of courses, students reach eight (08) levels

based on CEFR (Common European Framework of

Reference for Languages): Beginners A1 (Parts 1

and 2), Basics A2 (Parts 1 and 2), Intermediate B1

(Parts 1 and 2) and Intermediate Advanced B2 (Parts

1 and 2) and a subsequent section entitled Travel

Courses.

All levels put through a series of “learning units”

consisting of linguistic situational elements

presented by images. It starts with some sentences

AssessingandImplementingEnglish-learningMobileApplicationsinaUniversityGraduationProgram:SLA2.0

11

for listening and reading (matching), followed by a

dialogue performed by natives (listening skill also in

use here) with the possibility of reading it in English

or at an automatic translation to your mother tongue.

Continuing you find a “fill in the blanks” exercise

with the items learned. The pedagogical approach

here is mostly communicative and it aims at

bringing the student to an “on the street” linguistic

experience. Taking as an excerpt we will analyse the

Level Intermediate B1 Part 2/ “Holidays”. After

downloading the content you come across 3

sections: Vocabulary (expressions that are related to

the theme followed by more complex linguistic

structures), Dialogue (a “real-life” dialogue

containing the aforementioned structures in a daily

context) and Writing where you can answer a

question (related to the same theme) that will be

corrected by a native speaker afterwards. After

completion of every Section or Part and when

answers are mostly correct, the app awards you with

a number of “berries” that count as a reward to your

learning process.

Those corrections scaled in berries count as

Immediate Feedback (Bastien and Scapin, 2003) to

the student that sees his/her work valued. Moving

on, you have a series of sentences to put words in

order and finally the unit gets a “medal” for being

finished. We may point out here that it has an

interesting approach to beginners due to the fact that

it goes from teaching how to introduce yourself –

Part 1 exercise 1 - to stretches of some more

developed structures for certain social situations.

The User Control (Bastien and Scapin, 2003) at this

stage is 100%. At the moment of this writing, the

app does it in a more well-structured, reliable and

educational manner. Statistically, according to Alexa

(alexa.com), a website that registers application

users per country, Brazil is the number two user of

the Busuu platform with 8,3%; Russia is the leader

country with 12,1%. The following Figures 3, 4 and

5 illustrate a HCI of a lesson by Busuu

Figure 3. Figure 4. Figure 5.

5.2 Babbel

The initial screen also brings the registration step

and after that you go straight to the idiom

downloaded. Then, you have to choose where you

would like to start (Beginner or Advanced) and here

we find the first setback – no Intermediate status.

The user then goes through an association of

language used for introductions and daily use such

as “hello”, “please”, “goodbye”, “how are you?”

followed by a matching exercise that presents no

challenge even to “real” beginners. A matching

exercise works as a unit review. In the sequence you

find the “voice recording” exercise which is, in my

view, the best element of Babbel.

After you listened to the linguistic item spoken

by a native you have to repeat and the app will

accept the pronunciation as correct or not. Following

through, you then write in a spelling exercise the

items just learned which come presented in a

dialogue to fill. After completing two sets of them

you come across a writing exercise of the language

previously learned where you type/spell the same

words.

Unfortunately, only Part I is free and after

completion it charges you 9,95 Euros for a month.

Nevertheless, going to the Menu of the app you can

choose from a series of (free) thematic vocabulary

such as First Words and Sentences, Eating and

Drinking, Vacation, Human Relationships,

Transportation and Travel, Public Services, At

Home, and many others.

Taking one for a deeper analysis, we selected

Transportation and Travel due to its allure to

learning the idiom. It develops the segment into

isolated vocabulary for public transportation, for

cars, planes, boats, etc. Choosing one of them will

put the learner into an association of vocabulary to

pictures and to the listening of that word in L2. After

that, we come across a spelling exercise and

completion sentences where a British accent voice

reads the sentence for you after completion.

We have noticed great Compatibility and

Consistency (Bastien and Scapin, 2003) on this

reading + writing + listening activities; as they fulfill

real life communication settings. The HCI is

designed to take learners into the theme however I

found the illustration to be small and the fonts could

be bigger; taking into account that our research was

promoted in a 7-inch Samsung tablet or at the

Samsung S4 mini smartphone.

In app statistics, according to Alexa, Brazilian

users represent 8,7% of the downloads – 4

th

position.

CSEDU2015-DoctoralConsortium

12

An example of the HCI of Babbel is presented on

Figures 6, 7 and 8.

Figure 6 Figure 7 Figure 8

6 EXPECTED OUTCOME

The expected outcome will be presented in two

steps:

a) After a thorough qualitative analysis of the data

created from observations, interviews and oral

conversation in English with the participants and

the researcher own perception of the Virtual

Learning Environment apps, we will establish if

there is efficacy (through language progression)

on using the apps to improve English language

learning.

b) Subsequently to this efficacy confirmation, I will

design a curriculum modification to include the

implementation of the most adequate app on the

syllabus of the Graduation Course subjects

entitled English Language I and English

Language II at UNIT.

We remind our audience that most subject

students to be involved on this research (UNIT and

UNL) will not be fluent on the English language –

we aim for A1, A2 and B1 C.E.F.R. levels here and

therefore they might demonstrate a higher necessity

of a more guided or grammatical approach to

learning sometimes. As we said before, tablets and

smartphones are a reality nowadays as they can be

found in almost every household, classroom and

educational institution in both countries. Brazilians

(UNIT) as well as Portuguese students (UNL) will

certainly improve their overall knowledge learning a

lingua franca through some apps that can bring you

real learning possibilities for free or for some Reais

or Euros. Concluding with the reason why these

countries should learn English as soon as possible,

according to EF’s English Proficiency Global Index

- Brazil still stands at the 46

th

position (Low

Proficiency) while Portugal is doing a better work

but stands at the 19

th

position (Moderate

Proficiency), what it is not so adequate when

comparing to other European countries.

7 STAGE OF THE RESEARCH

The research is at its initial stages as the Doctoral

Program I attend just started last October 2014. Up

to this date, I have covered the mandatory Curricular

Units of the first semester, we are on semester #2

and the deeper literature review and field research

with the participants will start in February 2016. The

paper presented here brings the latest work of our

doctoral research.

REFERENCES

Anderson, T. (2008). The theory and practice of online.

learning. Athabasca University Press. Edmonton:

AUpress. Retrieved from: http://cde.athabascau.ca/

online_book/pdf/TPOL_book.pdf.

Banga, C. & Weinhold, J. (2014). Essential mobile

interaction design. Adisson-Wesley. Canada.

Barab, S., & Squire, B. (2004). Design-based reserach:

Putting a stake in the ground. The Journal of the

Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1-14. Retrieved from:

http://website.education.wisc.edu/kdsquire/

Bastien, C. and Scapin, D. (2003). Ergonomic criteria for

the evaluation on human-computer interfaces

Programe 3 – Artificial intelligence, cognitive systems

and man-machine interaction. Retrieved from:

http://www.irit.fr/~Mathieu.Raynal/docs/Ergonomic_

Criteria.pdf.

Blake, R. (2008). Brave new digital classroom: technology

and foreign language learning. Georgetown University

Press. USA. Retrieved from:

http://libgen.org/book/index.php?md5=B0B5398E866

52E65A13455AF299A02D9.

Bo-Kristensen, M., Ankerstjerne, N. O., Neutzsky-Wulff,

C., and Schelde, H. (2009). Mobile city and language

guides—New links between formal and informal

learning environments. Electronic Journal of e-

Learning, 7(2), 85–92. Retrieved from:

http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ867105.pdf.

Campos, A. (2008). A aquisição da língua inglesa usando

as novas tecnologias da informação e comunicação:a

apropriação do conhecimento. Masters Degree

Dissertation. Brasil. Editora UFS.

Chen, X. (2013). Tablets for informal Language Learning:

students use and attitudes. Language Learning and

Technology. Volume 17, Number 1. 2013. Retrieved

from:

http://llt.msu.edu/issues/february2013/chenxb.pdf.

Collins, A. (1992). Towards a design science education. In

E. Scanlon & T. O’Shea (Eds.), New directions in

AssessingandImplementingEnglish-learningMobileApplicationsinaUniversityGraduationProgram:SLA2.0

13

educational technology. Berlin. Springer. Retrieved

from: http://www.learning-theories.com/design-based-

research-methods.html.

Creswell, J. (2012). Educational research: planning,

conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative

research. Pearson Education. USA. Retrieved from:

http://libgen.org/book/index.php?md5=6D7DFDCAC

4C61DC924CC98E43F694F33.

Downes, S. (2012). Connectivism and connective

knowledge: essays on meaning and learning networks

Creative Commons License. Retrieved from:

http://online.upaep.mx/campusTest/ebooks/CONECTI

VEKNOWLEDGE.pdf.

Dugas, C. (2005). Adopter Characteristics and Teaching

Styles of Faculty Adopters and Nonadopters of a

Course Management System. PhD. Dissertation.

Retrieved from: http://personal.stevens.edu/~cdugas/

publications/CherylDugasDissertation.html.

Graves, K. (2000). Designing language courses: a guide

for teachers. TESL-EJ. (4) 4. Boston. Retrieved from:

http://www.cc.kyoto-su.ac.jp/information/tesl-ej/ej16/

r8.html.

Green, H.; Hannon, C. (2007). Their space: Education for

a digital generation. Demos. Tooley Street London

SE12TU2007.136. Retrieved from:

http://www.demos.co.uk/files/Their%20space%20-

%20web.pdf.

Jamieson, I. (1984). ‘Evaluation: a case of research in

chains?’ in Adelman, Clem (ed.), The Politics and

Ethics of Evaluation, Croom Helm, London. Retrieved

from: http://www.edu.plymouth.ac.uk/resined/

evaluation/

Herrington, J. (2007). Design-based research and doctoral

students: Guidelines for preparing a dissertation

proposal. Edith Cowan University Research Online.

ECU Publications Pre – 2011. Retrieved from:

http://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2611

&context=ecuworks.

Krashen, S. (1981). Second Language Acquisition and

Second Language Learning. University of Southern

California Publishing. USA.

Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2009). Will mobile learning change.

language learning? ReCALL, 21(2), 157–165.

Retrieved from:

http://oro.open.ac.uk/16987/2/AKH_ReCALL_Will_

mobile_learning_change_language_learning.pdf.

Lan, Y.-J., Sung, Y.-T., and Chang, K.-E. (2007). A

mobile-device-supported peer-assisted learning system

for collaborative early EFL reading. Language

Learning & Technology, 11(3), 130-151. Retrieved

from: http://ir.lib.ntnu.edu.tw/ir/retrieve/21086/meta

data_0111004_01_029.pdf.

Leu, D., Kinzer, C., Coiro, J. and Cammack, D. (2004).

Toward a theory of new literacies emerging from the

Internet and other Information and Communication

Technologies. In R.B. Ruddell, & N.J. Unrau (Eds.),

Theoretical Models and Processes of Reading (pp.

1570-1613). Newark, DE: International Reading

Association.

McKay, S. (2006). Researching second language

classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates, Inc. Retrieved from:

http://libgen.org/book/index.php?md5=927667e17d8e

755b721318461ce99a20.

Murray, G., Xuesong, G. & Lamb, T. (2011). Identity,

motivation and autonomy in language learning.

Second Language Acquisition Series. Trinity College

Publishing. Retrieved from:

http://libgen.org/book/index.php?md5=336034599e77

57bd9825a7cce25dd0b9.

Nation, I. & Macalister, J. (2010). Language curriculum

design. Routledge. USA. Retrieved from:

http://libgen.org/book/index.php?md5=C510B0A594

DF1E76E43EFA7127F94F95.

Oblinger, D. (2005). Educating the Net Generation

Educause. Retrieved from:

http://www.educause.edu/educatingthenetgen/Papert, S.

(1996). The connected family: bridging the digital

generation gap. Longstreet Press. USA.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants

On the Horizon 9 (5). Retrieved from:

http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-

20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20

-%20Part1.pdf.

Reeves, T. (2006). Design research from a technology

perspective. In J. van den Akker, K. Gravemeijer, S.

McKenney & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational design

research (pp. 52-66). London: Routledge. Retrieved

from: http://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?

article=2611&context=ecuworks.

Robinson, K. (2006). Sir Ken Robinson – How schools kill

creativity. [Video file]. Retrieved from:

http://www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_says_schools

_kill_creativity.

Sahin, I. (2006). Detailed review of Rogers’ diffusion of

innovations theory and educational Technology-

related Studies based on Rogers’ Theory. Retrieved

from: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED501453.pdf.

Slattery, P. (2006). Curriculum development in the

post- modern era. Taylor & Francis Group. New York.

Retrieved from: http://libgen.org/book/index.php?

md5=AFF7C5B44E9375CEF526B6E0013250AA.

Tapscott, D. (1998). Growing Up Digitally: The rise of the

net generation. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Thorne, S. and Payne, J. (2005) Evolutionary Trajectories,

Internet-mediated Expression, and Language

Education. CALICO, 22. Retrieved from:

http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/wll_fac/17/

van den Akker, J., Gravemeijer, K., McKenney, S., &

Nieveen, N. (2006). Introducing educational design

research. In J. van den Akker, K. Gravemeijer, S.

McKenney & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational design

research (pp. 3-7). London: Routledge. Retrieved

from: http://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=

2611&context=ecuworks.

Valk, J.H., Rashid, A., and Elder, L. (2010). Using mobile

phones to improve educational outcomes: An analysis

of evidence from Asia. International Review of

Research in Open and Distance Learning. Retrieved

CSEDU2015-DoctoralConsortium

14

from: http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/

view/794/1487.

Vavoula, G. (2005). A Study of Mobile Learning Learning

Practices. Retrieved from:

http://www.mobilearn.org/download/results/public_deliver

ables/MOBIlearn_D4.4_Final.pdf.

Vygostky, L. S. (1985). Thought and Language

Cambridge, The M.I.T. Press.

AssessingandImplementingEnglish-learningMobileApplicationsinaUniversityGraduationProgram:SLA2.0

15