Computer Games for Older Adults beyond Entertainment

and Training: Possible Tools for Early Warnings

Concept and Proof of Concept

Béla Pataki

1

, Péter Hanák

2

and Gábor Csukly

3

1

Department of Measurement and Information Systems, Budapest University of Technology and Economics,

Műegyetem rakpart 3., Budapest, H-1111, Hungary

2

Healthcare Technologies Knowledge Centre, Budapest University of Technology and Economics,

Műegyetem rakpart 3., Budapest, H-1111, Hungary

3

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Semmelweis University, Balassa utca 6., Budapest, H-1038, Hungary

Keywords: Computer Games, Serious Games, Silver Games, Cognitive Disorders, Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI).

Abstract: Old age cognitive deficit is a relatively new mass-phenomenon due to the fast growth of older populations,

and the fact that dementia is chronic, progressive, long lasting and, so far, incurable. However, in the early

phase of cognitive decline symptoms do not manifest clearly, and may remain unexplored for a longer peri-

od of time. Clinical tests, using either paper-based or computerized methods, are made quite infrequently,

providing too sparse snapshots of the cognitive performance. In this paper, computer games are proposed

for home monitoring of possible significant changes in mental state. This approach is advantageous as it is a

regular but voluntary method. This way, more frequent assessments are possible than with the traditional

clinical test scenario. Problem descriptions, possible solutions and methods, presented in this paper, have

been elaborated in the AAL project Maintaining and Measuring Mental Wellness (M3W). The ultimate goal

of the project is to develop a computer game toolset and a methodology for monitoring the mental state of

older adults remotely (at home). As it is a complex task, only basic considerations and concepts, a few chal-

lenges, problems and potential solutions, the proposed architecture, and the proofs of the concept are pre-

sented in the paper.

1 INTRODUCTION

The world's population is aging: “those aged 65

years or over will account for 28.7 % of the EU-28’s

population by 2080, compared with 18.2 % in 2013.

As a result of the population movement between age

groups, the EU-28’s old-age dependency ratio is

projected to almost double from 27.5 % in 2013 to

51.0 % by 2080 (Eurostat, 2014).

Older adults have to cope with physical and men-

tal impairments. Old age cognitive deficit is a rela-

tively new mass-phenomenon due to the fast growth

of older populations, and the fact that dementia is

chronic, progressive, long lasting and, so far, incur-

able. According to Alzheimer's Research UK, “the

annual economic cost of dementia is nearly the same

as the combined economic costs of cancer and heart

disease” (Alzheimer’s, 2014). In December 2013,

the G8 dementia summit called for strengthening

and joining efforts to “identify a cure or a disease-

modifying therapy for dementia by 2025”, and

acknowledged prevention, timely diagnosis and

early intervention of dementia as innovation priori-

ties (Gov.UK, 2013).

Various paper- and object-based psychological

tests have been in use since the beginning of the 20

th

century, aiming at recognizing cognitive disorders.

Recently, their computerized variants as well as

neuroimaging methods have been available for diag-

nostic purposes in clinics. As these are expensive

and need the contribution of specialists, they are not

suitable for mass screening.

In this paper, we propose to use computer games

for the home monitoring of eventual significant

changes in mental state. This approach is advanta-

geous as it is a regular but voluntary method. This

way, more frequent assessments are possible than

with the traditional clinical test scenario.

Section 2 and 3 characterize briefly variants of

cognitive impairments and their recognition possibil-

ities. Section 4 presents the conceptual model of the

285

Pataki B., Hanák P. and Csukly G..

Computer Games for Older Adults beyond Entertainment and Training: Possible Tools for Early Warnings - Concept and Proof of Concept.

DOI: 10.5220/0005530402850294

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (AGEWELL-2015),

pages 285-294

ISBN: 978-989-758-102-1

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

proposed system for the assessment of mental

changes. Section 5 describes the system developed

in the Maintaining and Measuring Mental Wellness

(M3W) project: first, it summarizes the so-called

early pilot, then sketches the M3W ICT architecture,

presents the game categories, and finally introduces

the logging and scoring procedures. Section 6 dis-

cusses evaluation challenges and proposes several

approaches. Section 7 presents proofs of the detec-

tion method. Finally, Section 8 summarizes our

findings, and shows directions for further work.

2 COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENTS

The early sign of having a higher risk for a patholog-

ical decrease in cognition is called Mild Cognitive

Impairment, abbreviated as MCI (Werner, 2008); in

this state, conversion to dementia is much higher

(>10-15%) than with healthy older people. The im-

portance of recognizing the population at risk is

underlined by scientific data showing that treatment

initiated in the early phase can prolong this phase,

and improve the ability for independence (Budd,

2011). However, in the early phase of cognitive

decline symptoms do not manifest clearly, and may

remain unexplored for a longer period of time. Fur-

ther, it is not easy to identify the stage at which the

process becomes abnormal, and the affected person

requires serious attention, perhaps medical interven-

tion, as MCI is a set of symptoms rather than a spe-

cific medical condition or disease. A person with

MCI has subtle problems with one or more of the

following (Alzheimer’s, 2015):

• day-to-day memory,

• planning,

• language,

• attention,

• visuospatial skills (the ability to interpret objects

and shapes).

With early detection of MCI people at risk can

get advice, support and therapy in time. Early diag-

nosis also allows people to plan ahead while they are

still able to do so. As said above, cognitive decline

can be significantly slowed down in an early stage.

However, early detection is rare because cognitive

tests are usually performed only when there are

clear signs of cognitive deficit. The natural denying

effect by the older adult, their family members and

friends may lead to significant additional delays.

Traditional, validated, paper-based clinical tests

constitute the gold standard but they have several

drawbacks. Such tests require specialist centres and

highly trained professionals. Therefore, there is a

growing interest in the development of computerized

cognitive assessment batteries (Cantab, 2015),

(MindStreams, 2015), (Dwolatzky, 2011). However,

clinical tests, using either paper-based or computer-

ized methods, are made quite infrequently, provid-

ing too sparse snapshots of the cognitive perfor-

mance.

3 GAMIFYING MCI DETECTION

Regular home – remote – monitoring of changes in

mental state offers a powerful alternative, even if it

allows only relatively noisy and less targeted meas-

urements. It has the advantage of frequent assess-

ments, and thus it offers the possibility of evaluating

temporal trends. Current computerized and clinically

validated tests are not suitable for this purpose as

they have been developed for professional use; in

consequence, they are expensive, not entertaining,

and require the presence of medical staff. Therefore,

new measurement methodologies should be devel-

oped and validated, specifically for this strategy.

As more and more older adults use computers,

and many of them play computer games regularly,

this activity can be exploited for measuring their

performance in those games. According to some

experimental studies, this performance is related to

their cognitive state. In consequence, there is a

growing interest in the development of special com-

puter games for cognitive monitoring and training

purposes, addressing specific cognitive domains,

such as verbal fluency (Jimison, 2008), executive

functions (López-Martínez, 2011), or perceptual and

motor functions (Ogomori, 2011).

A major challenge in using computer games in-

stead of cognitive tests is that entertainment capabil-

ity and measurement power pose contradictory re-

quirements. There are three approaches in game

development for older adults, namely

• adapting well-known, popular games (e.g.,

chess, Tangram or Tic-tac-toe (Menza-Kubo,

2013), Find the Pairs, Freecell (M3W, 2015);

• transforming special clinical tests, e.g., Corsi

block-tapping, paired associates learning, Wis-

consin card sorting (M3W, 2015), into games;

• developing new games specially designed for

this purpose (López-Martínez, 2011).

Regular monitoring may be (1) controlled or (2)

voluntary. Controlled monitoring works only with a

highly motivated minority; since most older adults

are mentally healthy in the early monitoring period

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

286

(i.e., before detecting a decline), they deny to partic-

ipate in controlled monitoring as it seems to under-

mine their preferred independence.

Our basic idea is the following: with regular but

voluntary use of computer games developed or

modified specifically for older adults, we may be

able to measure the mental changes and tendencies

over time in an entertaining way.

The problems, possible solutions and methods,

presented in this paper, are based on a recent re-

search project, Maintaining and Measuring Mental

Wellness (M3W, 2015), (Sirály, 2013), (Hanák,

2013). The ultimate goal of the project is to develop

a toolset and a methodology for monitoring the men-

tal state of older adults remotely (e.g., at home),

which is a very complex task. Therefore, only the

basic considerations and concepts, a few challenges,

problems and solutions, the proposed architecture,

and the proofs of the concept are presented in this

paper. Many other important problems, such as

player motivation and game selection, are not dis-

cussed here in detail.

One of the biggest challenges is to find the right

balance between entertainment capability and

measurement power. In order to cope with this chal-

lenge, the game set has been evolving since our

early pilot experiments, performed in 2012/2013.

Unfortunately, the changing of the games and the

collected data poses another significant challenge as

basically non-comparable data have to be compared

somehow in the long run. To this end, we propose a

kind of sensor-fusion approach that will be described

later, in Section 6.

4 CONCEPTUAL MODEL

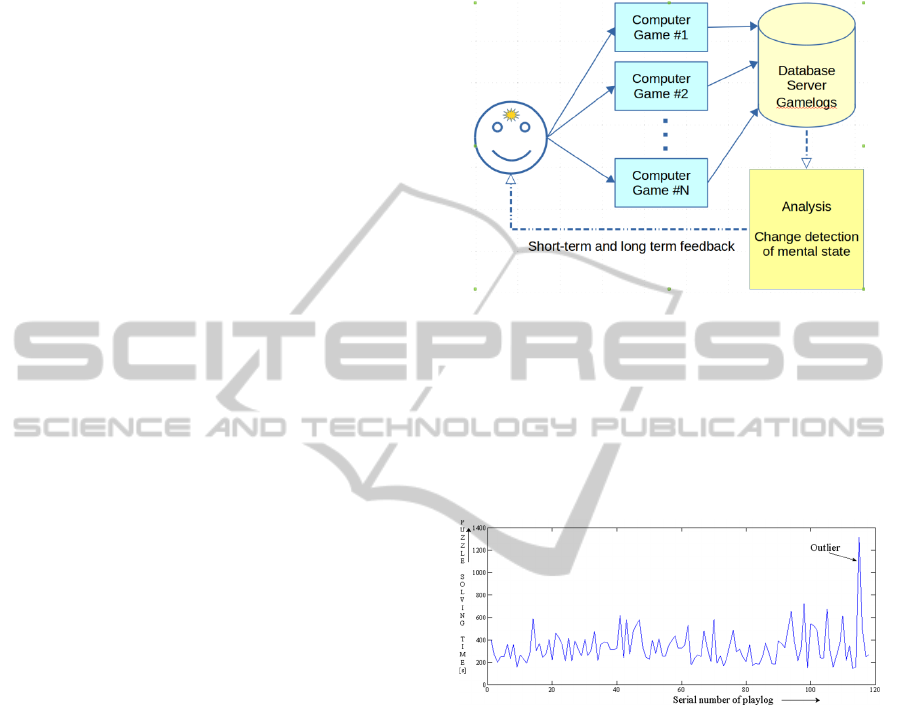

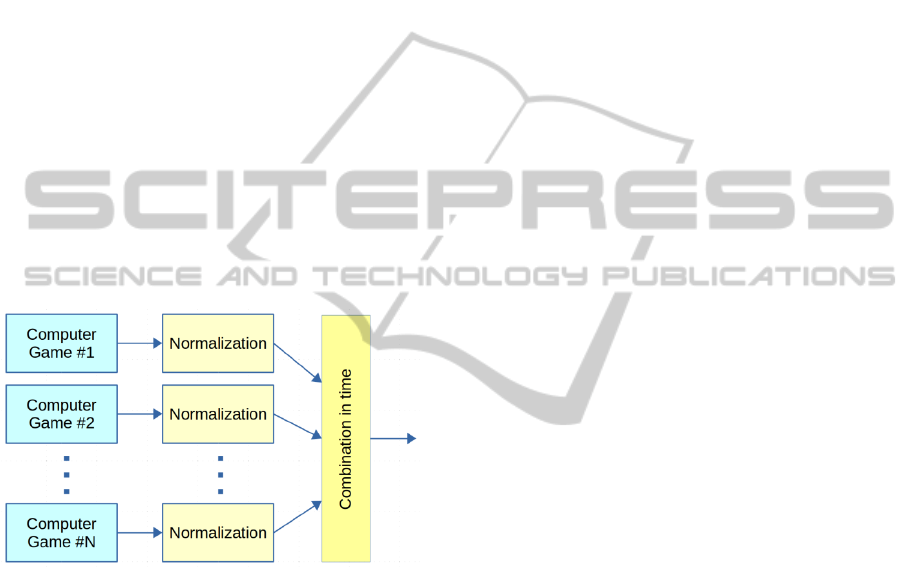

The basic conceptual model of the proposed system

is shown in Figure 1. The final goal is to provide

appropriate long-term feedback (warning) to the user

or to a caregiver, family member, medical expert,

etc., when a significant change in mental state has

occurred. Short-term feedback is needed as motiva-

tion to continue participation in the monitoring.

Several games have been considered. Most of the

chosen ones are logical puzzles, or games that need

the intensive use of the short-term memory (its dete-

rioration is one of the best indicators of MCI), but

other important cognitive abilities and processes

(attention, executive function, comprehension, lan-

guage skills, planning, decision making, etc.) are

targeted as well (see details in Section 5).

Two types of basic parameters are measured cur-

rently: the solving time of the puzzle and the amount

of the good and bad steps taken during the solution.

Figure 1: Basic conceptual model of the cognitive state

evaluation system.

In Figure 2, a typical series of performance is

shown for a player playing the same game nearly

120 times. The time span of that series was 14

months. The performance is fluctuating around a

mean value, and there is an outlier far from the usual

values.

Figure 2: Typical performance series of a player measured

with a given computer game.

Beyond the general problems of such systems

(e.g., data privacy concerns), this approach has its

special challenges:

1) How to measure cognitive performance using

computer games?

2) How to cope with the typically heavy noise of

the uncontrolled (home) measurement envi-

ronment?

3) How to motivate people to take part in the long

run?

4) How to compare performance shown in differ-

ent games, which is basically a special sensor-

fusion problem?

After describing the ICT architecture and com-

ponents in the next section, we shall propose various

ComputerGamesforOlderAdultsbeyondEntertainmentandTraining:PossibleToolsforEarlyWarnings-Conceptand

ProofofConcept

287

approaches and procedures as possible answers to

these challenges.

5 ICT ARCHITECTURE AND

COMPONENTS

5.1 Early Pilot

In a one-year pilot study in 2012/2013, more than 50

volunteers registered to take part and help evaluate

the framework and the games developed at that time.

Due to the voluntary nature of the project only about

20 of them played regularly for nearly one year at

home and in an elderly home. (Of course, the paral-

lel development of the program package was a

drawback for the players.) The average age of these

regular players was 70.3, and the standard deviation

was 10.9 years.

Because of the relatively short test period, its rel-

evance was limited in regard to mental aging; none-

theless, we found some findings as clearly important

for the long run as well. Parallel to the home moni-

toring pilot study, clinical examinations on patients

with mental problems (MCI, Alzheimer’s disease,

etc.) were also performed (Sirály, 2013); (Sirály,

2015).

The software package for the early pilot was

written in Java, and had to be downloaded and in-

stalled; it was a challenge for many older adults.

Recent advancements of internet and browser tech-

nologies have made it possible to develop the soft-

ware in HTML5, JavaScript and PHP in the second

phase, go online, and become available on various

platforms, including touchscreen devices.

5.2 Global Architecture

The current implementation is composed of the

M3W frame and the set of games – the Game Ser-

vice. The M3W frame ensures a unified layout and

provides various services to the games, incl. com-

pleting and passing the gamelogs to the Data Ser-

vice. The Game Service can be displayed in a big-

enough iframe in any webpage. Authentication and

authorization – i.e. provision of a User Register – is

the responsibility of the webserver hosting the Game

Service.

For older adults, especially for those with limited

computer skills and, to some extent, affected by

cognitive impairment, ease of use (incl. easy regis-

tration and login) is especially important. For them,

modern Single-Sign-On (SSO) solutions can be very

helpful. Therefore, despite the immature status of

and frequent changes in SSO applications, we have

implemented such services based on an open source

solution, simpleSAMLphp (SSP) that is used world-

wide in higher education. With SSP, on the one

hand, a so-called identity provider (IdP) can inte-

grate authentication services of a number of external

authentication sources, incl. social login services

offered by social network providers, such as Google,

Facebook and LinkedIn. On the other hand, a web-

service can be amended by a so-called service pro-

vider (SP) with SSP such that this webservice can

utilize the authentication mechanisms of one or more

IdPs.

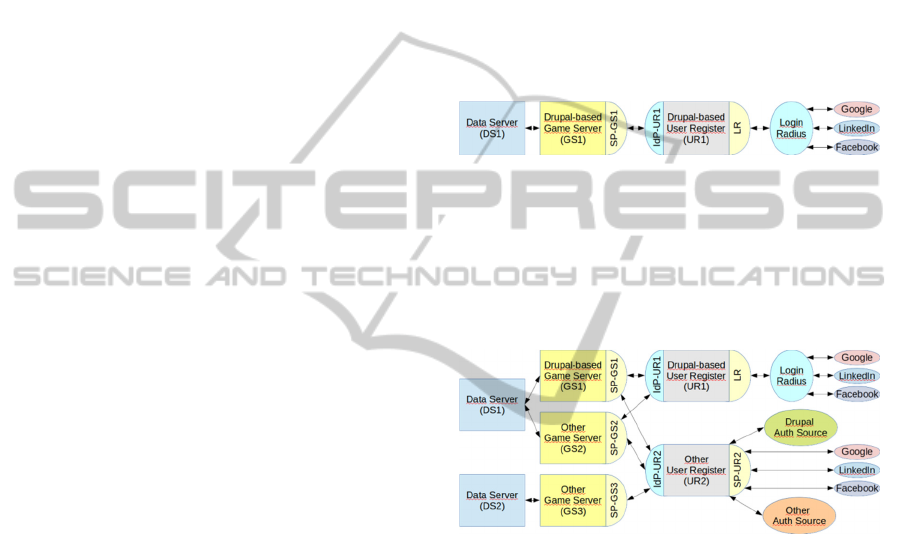

Figure 3: Simple distributed architecture.

In the simplest case, User Register (UR), Game

Service (GS) and Data Service (DS) can run on the

same server (e.g., a Drupal 7 instance may be used

for this purpose). A simple distributed architecture is

depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 4: Complex distributed architecture.

Sometimes more sophisticated architectures are

needed. For example, with a high number of users

the load on a single GS may be too high, and a sec-

ond GS has to be added. In another situation, privacy

concerns or regulations might require that the UR

remain under the authority of an institution, or with-

in a country, so the UR must be duplicated or even

multiplied. Further, the collected data might be con-

sidered as sensitive despite that they contain no

personal data only an integer player identifier. In

such situations, it must be ensured that the DS be

duplicated or multiplied. SSP ensures the necessary

scalability and connectivity also in such cases. Fig-

ure 4 illustrates a situation where a complex M3W

system is realized by two DS, three GS, three UR

and six SSP instances, and other external services.

Note that both GS and UR services can be real-

ized without Drupal.

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

288

5.3 Cognitive Abilities and Game

Categories

Cognitive abilities are mental skills needed to carry

out tasks. They are mechanisms of how we learn,

remember, plan, execute, solve problems, pay atten-

tion, etc. Major categories of cognitive abilities are

perception, attention, memory, motor skills, lan-

guage skills, visual and spatial processing, and

executive functions.

Cognitive tests – traditional or computerized –

are designed to measure one of these abilities in

order to maximize their assessment capability; they

are not designed for frequent use. However, in case

of cognitive games, their measurement potential

must be accompanied by entertaining power as they

must motivate the user to play regularly for a long

time.

Figure 5: Snapshot of the M3W playground.

The M3W set of games tries to satisfy both ma-

jor requirements. Each game belongs to at least one

of five categories: attention, planning, language

skill, memory and execution (see Figure 5). Most

games try to focus on one cognitive category; e.g.,

Birds, Boxes, Differences or Lost Lego deals with

attention, Find the Pairs with memory, Gopher with

(motor) execution. Games belonging to category

planning are usually more complex, i.e. more de-

manding; examples for such games are FreeCell,

Sudoku, Blocks, Planargame, or Labyrinth (because

of its complexity the latter was added more for en-

tertainment than assessment).

Additionally, a few known tests are also made

available in the category cognitive tests. They may

be used as sort of reference: the results gained with

these tests may be compared with the results gained

with the games.

5.4 Game Logging

As mentioned in Section 4, the solving time and the

amount of good and bad steps have recently been

used for statistical analysis. However, parameters

describing the game settings, the gaming platform

and the course of playing the game are also recorded

in the game logs; these data can and will be used

later to compute suitable indicators.

Settings are game-specific such as difficulty level,

word length and language, turning or moving speed,

appearance time, board size, etc. Platform parame-

ters include monitor resolution, browser version,

operating system, the use of mouse, touchpad or

touchscreen, etc. The course of playing the game is

described by all significant mouse clicks or touches

with timestamps.

Game logs are json-objects, saved into files.

Each game log consists of five components and

several subcomponents:

1. Game descriptor

numeric identifier, name category, version

2. Player identifier

numeric identifier

3. Parameters:

date, options, seed, platform, log version

4. Events

game-specific series of time-stamped event-

items

5. Statistics

score, play time, game-specific aggregated val-

ues

5.5 Score Calculation

Scoring follows the same principle and procedure

for every game. The highest reachable score depends

on difficulty settings. On the lowest and highest

difficulty levels the maximal score is 600 and 1000,

respectively. High score limits on intermediate diffi-

culty levels (i.e., between the lowest and highest

levels) are distributed linearly. Difficulty levels are

defined in the game settings.

In every game, various faults may occur that

may lead to score deductions. Fault calculation may

take playtime, bad move, wrong mouse click, erro-

neous selection, etc. into account. The extent or

seriousness of a fault is called fault value. For each

fault, there is a threshold, a limit and a weight. A

fault value exceeding the threshold results in score

deduction. A fault value reaching the limit causes

maximal weighted deduction.

ComputerGamesforOlderAdultsbeyondEntertainmentandTraining:PossibleToolsforEarlyWarnings-Conceptand

ProofofConcept

289

The common score calculator has four argu-

ments: currentValues, goodValues, acceptableVal-

ues and weights.

Fault values are passed to the score calculator as

currentValues, threshold values as goodValues,

limits as acceptableValues, and weights as weights.

With weight=1.0, a fault value reaching the limit

sets the deduction to produce a score element of 333.

Smaller weights produce smaller deductions, larger

weights larger deductions.

The score calculator aggregates the deductions

caused by various faults. During calculation, when

the final score reaches 400, further deductions are

reduced to one-third of their original values. When

the final score reaches 200, score calculation stops.

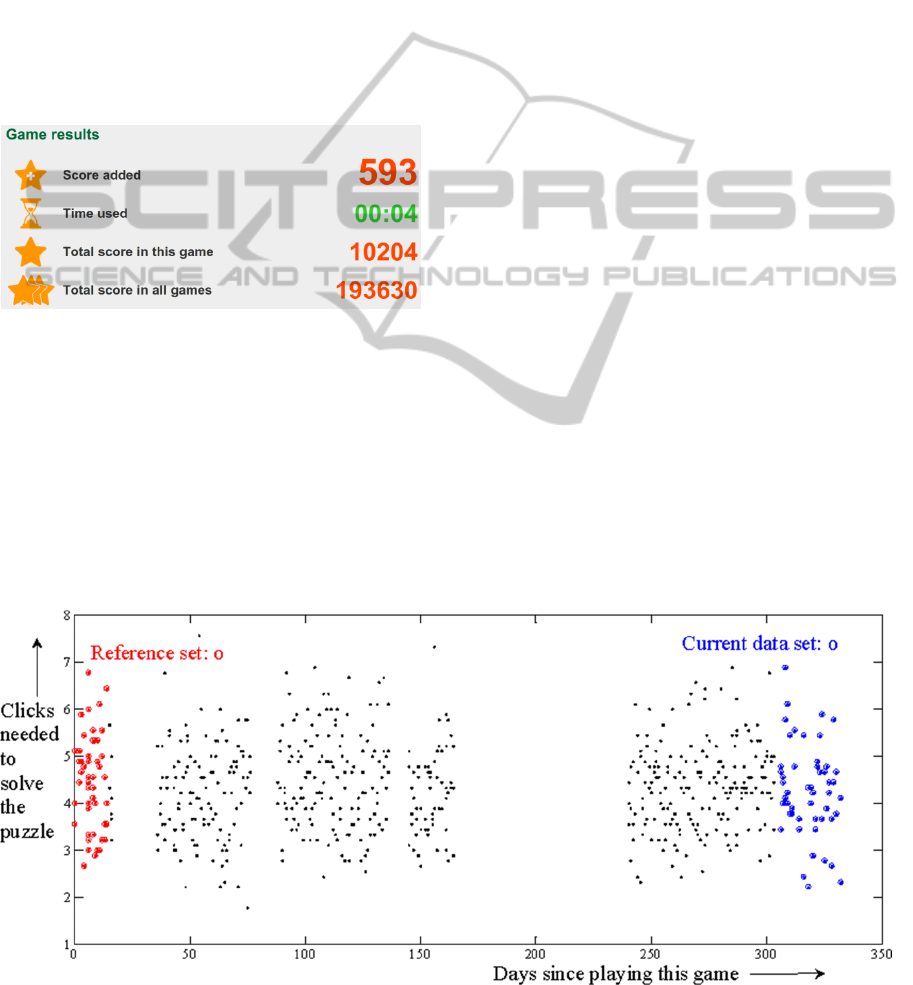

Figure 6: Snapshot of a game result.

Primary score calculation is performed by the

games themselves. The primary score is the basis for

the immediate feedback to the user (see Figure 6).

Secondary score calculation is performed when

stored game logs are reprocessed and uploaded into

the database. The secondary score is used as an

indicator of cognitive performance. (More sophisti-

cated indicators might also be computed.) Since all

original game logs are stored, score calculation may

be refined later in order to improve our assessment

methods, and thus the recognition of changes in

mental wellness.

6 SUGGESTIONS TO MEET THE

CHALLENGES

To assess the cognitive state, it is assumed that per-

formance measured in playing computer games

correlates with cognitive wellness. As it will be

shown in Section 7, there is indirect evidence that

this assumption is valid.

The measurement of the mental state on an abso-

lute scale is very difficult as it depends on education,

physical health, etc. For our purpose, fortunately, it

is enough to detect only the change in a person’s

cognitive performance, and it is an easier task.

For measuring change, a reference is needed.

There are two possibilities: the performance of a

person can be compared to the performance of other

persons in a reference group; or it can be compared

to a previously measured reference of the same per-

son.

Because the person-to-person comparison is af-

fected by several parameters that are unknown with

this voluntary, uncontrolled method (education,

physical abilities, family conditions, profession,

environment, etc.) the comparison to the same per-

son’s previous performance was chosen (c.f. Figure

7).

To cope with the heavy noise present, data are

cleaned before analysis: outliers are detected and

omitted. Outliers are usually caused by inter-

rupts(due to social or physiological reasons). There

is another noise term caused by random differences

Figure 7: Performance measure of a player during nearly one year.

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

290

between consecutive puzzles, by minor environmen-

tal disturbances, by tiredness, etc. It is reasonably

assumed that the short-term fluctuations are zero-

mean, stable independent random variables. To

decrease the assessment error caused by this noise

term, performance measured only in a single game

will not be evaluated; in its stead, performance

measured on a reference set will be compared to

performance on the current set (c.f. Figure 7).

While our goal is to detect the decline of perfor-

mance, in some periods improvements can occur as

well. The assumption is that the decline is preceded

by a longer period where the situation is stable or

deteriorating very slowly. Therefore, the reference is

chosen as the group of consecutive games in which

the person had shown stable performance (see Fig-

ure 7 and Figure 10).

The puzzle difficulty and the short-term change

of cognitive performance are both zero mean ran-

dom variables. The very slow, long-term change of

the cognitive state is modelled differently. There-

fore, if a change is detected in one of the integral

characteristics (mean, median, standard deviation),

or generally in the distribution of the composite

random variable (mental state plus game noise), then

it is caused by the slowly changing component mod-

elling the mental state.

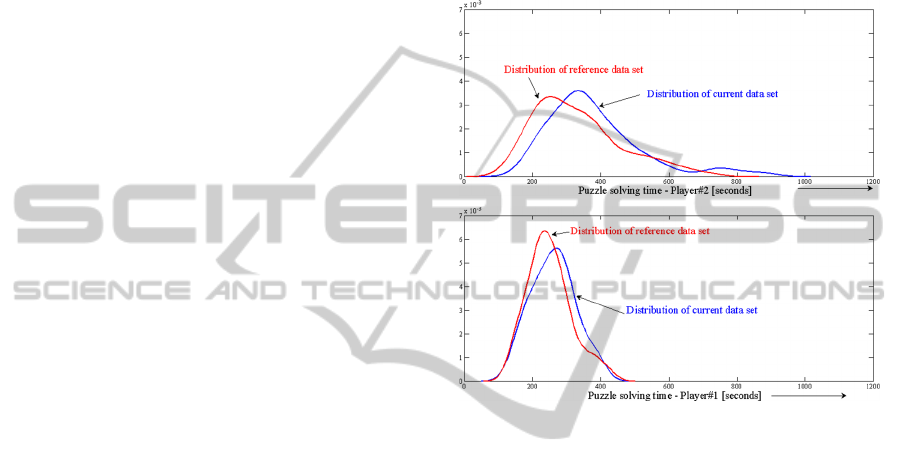

In Figure 8, the distributions of the same perfor-

mance measure (puzzle solving time) in the same

game are shown for two players. In each diagram

two performance distributions of the given player

are drawn (red line: distribution of reference data,

blue line: distribution of current data). Of course, the

performance distributions of the same players in two

time periods will not be exactly the same, but statis-

tically the identical distribution assumption cannot

be rejected. However, for different players, not only

the parameters of the distributions differ from player

to player but the shapes are different as well.

It was investigated whether the parameter distri-

butions are Gaussian ones or not. The Lilliefors test

rejected the normality hypothesis in most of the

cases. Therefore, nonparametric tests are suggested

to check if the distribution has not changed the hy-

pothesis.

6.1 Nonparametric Tests

There are several applicable nonparametric tests, for

example the Mann-Whitney U test, the Kolmogorov-

Smirnov two-sample test, the Wilcoxon signed-rank

test, etc. Any of these methods can be used to com-

pare the distribution of the reference subset with the

distribution of the currently examined subset of the

time series, and normality is not necessary. If we

detect a difference between the distributions of the

two sub-samples, and the current part of the series

has a smaller average (of ranks, of scores, etc.), then

the player shows performance degradation. Up to

now, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test and

the chi-square test were extensively used. It will be

investigated later which is the optimal statistical

hypothesis test for this kind of problems.

Figure 8: Performance measure distributions of two play-

ers.

The following findings were obtained:

• The results gained with the Kolmogorov-

Smirnov two-sample test and the chi-square test

have confirmed that both the stability and the

change in the parameters are reliably estimated

with these statistical hypothesis tests.

• In case of a new game a learning phase occurs

when results are improving. The reference is

meaningful only when the performance is stabi-

lized (c.f. Figure 11).

6.2 Sensor Fusion with Games as

Sensors

Motivation of older adults to play frequently and

regularly the computer games is one of the most

important challenges to solve. Early detection is the

purpose; but the main problem is that nobody knows

when the abnormal change will happen; maybe only

after many years, or in some persons’ life never.

Therefore, the motivation must be kept alive proba-

bly for years. It is a very complex problem in itself;

so only some aspects are discussed here. A basic

ComputerGamesforOlderAdultsbeyondEntertainmentandTraining:PossibleToolsforEarlyWarnings-Conceptand

ProofofConcept

291

assumption is that although there is an intrinsic mo-

tivation that everybody wants to sustain mental

abilities and an independent life of good quality,

generally it is not enough as a motivation in the

long-run. There must be other, extrinsic motivations,

too, e.g., entertaining ways of measurement, and

short-term, immediate feedback (c.f. Figure 1), en-

couraging the user to play further (e.g., scores, sym-

bolic rewards, encouraging messages).

Unfortunately, most people do not enjoy playing

the same game for years. Therefore, in different time

periods different games will be played by the same

person. In order to preserve the level of motivation

of the players, various games are offered (c.f. Figure

1 and 5). – In addition, as mentioned earlier, repro-

grammed or improved games and more sophisticated

logging may replace older ones as assessment meth-

ods are improving while time passes by, or technol-

ogy changes occur. – The performance indicators

measured with different games should somehow be

compared to each other. This implies a sensor fu-

sion and estimation problem; this was discussed in

our previous paper (Breuer, 2015).

Figure 9: The sensor fusion architecture.

In Figure 9, the sensor fusion scenario is illus-

trated. Architecturally, the scenario is a usual sensor

fusion arrangement where computer games are the

sensors. The most important difference is that in a

usual sensor fusion arrangement the sampling is

regular, typically periodic, and the sensors are sam-

pling parallel in the same time instant. In the com-

puter game fusion scenario only one game (sensor)

is used in a time instant, and the sampling intervals

are irregular. Therefore, the currently suggested

method is to normalize all the performance results to

the same zero-mean series, and combine the results

in time to form one combined time-series. In the

future the possibility of applying other fusion meth-

ods will be investigated.

In Figure 7, another effect is clearly present:

there are gaps in the playing activity due to health

problems or social reasons. Analysis of the data gaps

has shown that a few week long interrupts do not

change the performance significantly.

7 PROOF OF THE CONCEPT

Due to the long time needed to detect a critical cog-

nitive change, no direct proof could be collected

during the project till now. Nonetheless, by analyz-

ing the game logs (more than 50 voluntary persons

produced about 150 thousand game logs by playing

the games during the second pilot) some important

facts can be shown.

To provide some calibration, one of the comput-

erized cognitive tests (Paired Associates Learning,

PAL) was implemented in the M3W project, and

players were asked to perform it. Studies have

shown that MCI patients performed poorly on this

test (Égerházi, 2007). Analyzing the performance of

the voluntary players, it turned out that their perfor-

mance shown in the computer games correlates to

their performance measured by the PAL test (Sirály

2013), (Sirály, 2015).

In the PAL test, cards turn up in random posi-

tions after each other for 3 seconds, with abstract

shapes shown on one or more cards. Other cards

remain blank depending on the difficulty level.

When all shapes have been shown, the previously

shown shapes appear one by one in the centre of the

play area, and the player has to choose the card

where that shape has appeared earlier. The test con-

sists of five different levels in eight stages in total,

while the number of the shapes increases from 1 to 8

on the different stages. The player has 10 trials to

complete a given stage, otherwise the test ends. The

arrangement of the cards is asymmetric in the test,

and it changes from stage to stage.

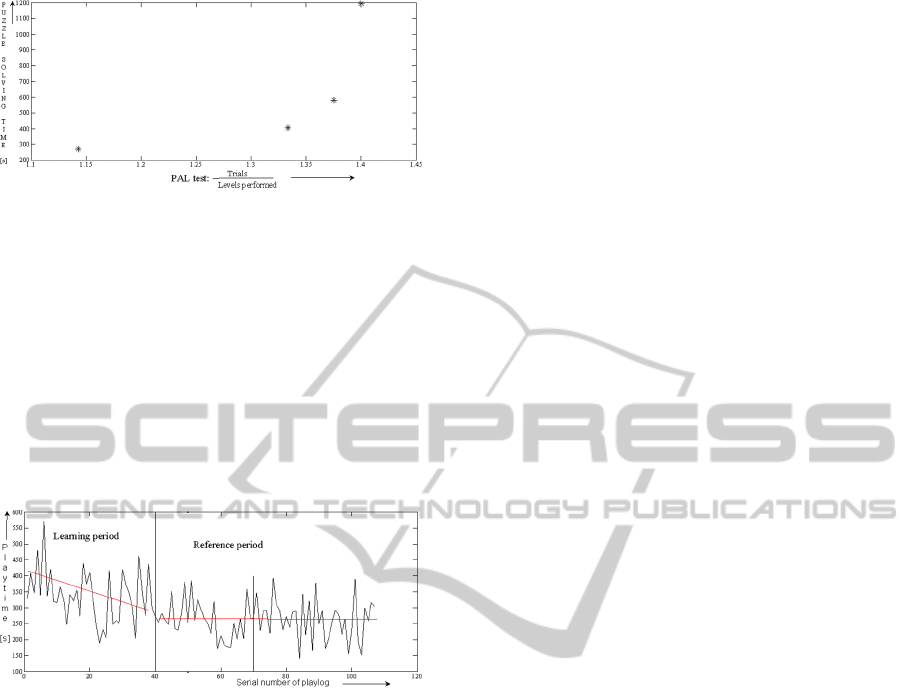

In Figure 10, PAL test performance versus aver-

age puzzle solving time of four players is shown. The

PAL test was characterized by the trials needed to

reach the highest level performed by the given play-

er. Although there were much more participants who

performed PAL tests, these 4 players were selected

for demonstration as they all played more than 90

Freecell games. The outliers were omitted, and the

averages of the playtimes were taken.

In a current study (Sirály, 2015) brain magnetic

resonance (MR) examination was performed on 34

healthy older adults. Beyond the MR examination,

paper based and computerized neuropsychological

tests (i.e., PAL test) and computer games were ap-

plied. There was a correlation between the number

of attempts and the time required to complete the

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

292

Figure 10: Performance reached at PAL tests and playing

one of the games.

Find the Pairs (also called Memory) game and the

volume of the entorhinal cortex, the temporal pole,

and the hippocampus. There was also a correlation

between the results of the PAL test and the Find the

Pairs game.

Although no healthy

→

MCI transition occurred

during the research period, the other change: signifi-

cant improvement was detected several times. In

Figure 11, performance of a player learning a new

game is shown.

Figure 11: Performance of a player learning a new game.

Applying the Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample

test, the same distributions null hypothesis is

• rejected for the learning period while compared

to the reference period (p= 0.0005),

• accepted for the first and second halves of the

reference period (p=0.28).

8 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

Home monitoring of possible significant changes in

mental state using computer games has been pro-

posed. This approach is advantageous because it is a

regular but voluntary method. Some of the problems

have been analyzed, and solutions have been sug-

gested. The system assumes voluntary participation;

therefore, various games have been developed to

sustain motivation in the long run. In the game bat-

tery there are both well-known, popular games and

modified clinical tests; it is continuously evolving.

For change detection in cognitive performance

the comparison of actual data against historical data

gained from the very same person is proposed, i.e. a

reference set of performance results are to be com-

pared to the current set of results using statistical

hypothesis tests. The null hypothesis is that the two

sets are of the same distribution. Until the null-

hypothesis cannot be rejected, the stability of the

mental state can be assumed.

In the future,

• further pilots have to be launched to validate the

method by more clinical tests,

• the most appropriate games for both entertain-

ment and measurement purposes should be fur-

ther investigated,

• the feasibility of multiplayer games is to be ana-

lyzed,

• collected but currently not analysed data should

be involved into the examinations,

• the potential in the evaluation of the failed

games should be investigated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was performed in the Maintaining and

Measuring Mental Wellness (M3W) project, sup-

ported by the AAL Joint Programme (ref. no. AAL-

2009-2-109) and the Hungarian KTIA (grant no.

AAL_08-1-2011-0005).

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribu-

tions of their project partners in Greece, Luxem-

bourg, Switzerland and Hungary. We would like to

express our special thanks to

1. E. Sirály, Semmelweis University, for her con-

tribution to the clinical examinations with real

patients using the PAL test and a selection of

the M3W games;

2. N. Kiss and Á. Póczik, Budapest University of

Technology and Economics, for the improve-

ment and unification of the logging and scoring

procedures;

3. L. Ketskeméty, Budapest University of Tech-

nology and Economics, for exploring and elab-

orating various statistical evaluation algo-

rithms.

REFERENCES

Alzheimer's Society, UK, Dementia statistics, 2014,

http://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/dementia-

statistics/ [retrieved: April, 2015]

ComputerGamesforOlderAdultsbeyondEntertainmentandTraining:PossibleToolsforEarlyWarnings-Conceptand

ProofofConcept

293

Alzheimer’s Society, Mild Cognitive Impairment, 2015.

http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/documents_i

nfo.php?documentID=120 [retrieved: April, 2015]

Breuer, P., Csukly, G., Hanák, P., Ketskeméty, L., Pataki,

B., 2015. Home Monitoring of Mental State with

Computer Games. In ACHI2015 8th International

Conference on Advances in Computer-Human Interac-

tions.

Budd, D. et al., 2011. Impact of early intervention and

disease modification in patients with predementia Alz-

heimer’s disease: a Markov model simulation. Clini-

coecon Outcomes Res, (2011) 3:189-195.

Cantab test battery, 2015. Cambridge Cognition,

http://www.cambridgecognition.com/ [retrieved: April,

2015]

Dwolatzky, T., 2011. The Mindstreams computerized

assessment battery for cognitive impairment and de-

mentia, PETRA’11 May 2011, pp. 501-504, ISBN:

978-1-4503-0772-7.

Égerházi, A., Berecz, R., Bartók, E., Degrell, I., 2007.

Automated Neuropsychological Test Battery (CAN-

TAB) in mild cognitive impairment and in Alzheimer's

disease. In Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology &

Biological Psychiatry 31 (2007) 746–751.

Eurostat, Population structure and ageing. 2014,

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.

php/Population_structure_and_ageing

[retrieved: April, 2015]

Gov.UK, G8 dementia summit agreements, 2013,

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/g8-

dementia-summit-agreements [retrieved: March, 2015]

Hanák, P., et al. 2013. Maintaining and Measuring Mental

Wellness, Proc. of the XXVI. Neumann Kollokvium,

Nov. 2013, pp. 107-110 (in Hungarian).

Jimison, H., Pavel, M. Le, T., 2008. Home-Based Cogni-

tive Monitoring Using Embedded Measures of Verbal

Fluency in a Computer Word Game, 30th Annual In-

ternational IEEE EMBS Conference, Aug. 2008, pp.

3312-3315. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2008.4649913.

López-Martínez, A., et al, 2011. Game of gifts purchase:

Computer-based training of executive functions for the

elderly, IEEE 1st International Conf. on Serious

Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH), Nov.

2011, pp. 1-8, Print ISBN:978-1-4673-0433-7 DOI:

10.1109/SeGAH.2011.6165448.

M3W Maintaining and Measuring Mental Wellness, 2015.

AAL Joint Programme project (ref. no. AAL-2009-2-

109) https://m3w-project.eu/ [retrieved: April, 2015]

Menza-Kubo, V., Morán, A., L., 2013. UCSA: a design

framework for usable cognitive system for the wor-

ried-well, Personal Ubiquitous Comput. Vol. 17, Issue

6, Aug. 2013, pp. 1135-1145. ISSN: 1617-4909. DOI:

10.1007/s00779-012-0554-x.

MindStreams, 2015. http://www.mind-streams.com/ [re-

trieved: April, 2015]

Ogomori, K., Nagamachi, M., Ishihara, K., Ishihara, S.,

Kohchi, M., 2011. Requirements for a Cognitive

Training Game for Elderly or Disabled People, Int.

Conf. on Biometrics and Kansai Engineering, Sept.

2011, pp 150–154, E-ISBN 978-0-7695-4512-7, Print-

ISBN 978-1-4577-1356-9,

DOI: 10.1109/ICBAKE.2011.30.

Sirály, E., et al., 2013. Differentiation between mild cogni-

tive impairment and healthy elderly population using

neuropsychological tests, Neuropsychopharmacol

Hung. (3), Sept. 2013, pp. 139-46.

Sirály, E., et al., 2015. Monitoring the Early Signs of

Cognitive Decline in Elderly by Computer Games: An

MRI Study, PLoS ONE. 2015; 10(2):e0117918.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117918.

Werner, P., Korczyn, A. D., 2008. Mild cognitive impair-

ment: Conceptual, assessment, ethical, and social is-

sues. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 3(3), 413–420.

ICT4AgeingWell2015-InternationalConferenceonInformationandCommunicationTechnologiesforAgeingWelland

e-Health

294