Certification and Legislation

An Italian Experience of Fiscal Software Certification

Isabella Biscoglio, Giuseppe Lami, Eda Marchetti and Gianluca Trentanni

Institute of Information Science and Technologies “Alessandro Faedo” of the National Research Council, Pisa, Italy

Keywords: Certification, Legislation, Fiscal Meters, Cash Register.

Abstract: The paper introduces the Italian Fiscal Software Certification scenario. Some concepts about certification

are illustrated. The cash registers, as specific kind of Fiscal Meter, are described and their adopted

certification process based on Italian legislation requirements is presented as well. Finally, the new related

technological challenges are discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

In an increasingly competitive global market, the

achievement of a certification by independent and

reliable bodies could be an instrument of great

economical and social benefit. The written assurance

that a product, process or service is compliant with

the requirements expressed by international

standards or national legislation, can represent an

added value expendable in the economical

agreements as well as an improvement of the

product, process or service quality. In some

commercial environments the certification is

mandatory before the product is marketed. This is

the case of the fiscal meters, i.e electronic devices

for storing, managing and tracing commercial

transactions. Usually the available fiscal meters can

be classified into two different entities: cash

registers and automated ticketing systems. In this

paper, only the former will be considered.

Currently many European countries are

introducing specific legislations to rule the

commercial transactions. Italy has been one of the

first adopting a specific set of laws that regulates the

fiscal transactions by means of the use of fiscal

meters (L. 18, 1983), becoming a reference for the

rest of the European countries. Usually the cash

registers certification process involves Universities

and research institutions in activities of inspection,

evaluation and control of the hardware and software

components in order to verify the compliance

against legislation requirements. In Italy the System

and Software Evaluation Centre (SSEC) of the

National Research Council has been working for a

couple of decades in the 3rd party software products

and processes assessment/improvement and

certification. Regarding to the cash registers, the

certification against the Italian fiscal legislation is

provided on behalf of the Italian Finances

Department.

In this context, the purposes of this paper are

outlined as follows: 1) Providing an overview of the

Italian experience of the fiscal software certification;

2) Describing the certification process by its

activities 3) Highlighting the challenges implied by

the technological evolution; 4) Presenting an early

work in progress on the storage of the quantitative

data about the certifications already performed.

In the following, an overview of the certification

and background main concepts are provided. In

Sections 3 the SSEC experience in the certification

process is presented and in Section 4 some questions

on technological evolution against legislation are

discussed and conclusions are provided.

2 FISCAL SOFTWARE

CERTIFICATION

In this section, some general concepts about

certification are introduced by pointing out the key

roles and the activities involved in any certification

process. Subsequently, the particular case of cash

register certification is shown.

2.1 Certification Scenario

About certification, the most relevant topics are

174

Biscoglio I., Lami G., Marchetti E. and Trentanni G..

Certification and Legislation - An Italian Experience of Fiscal Software Certification.

DOI: 10.5220/0005558901740179

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Software Engineering and Applications (ICSOFT-EA-2015), pages 174-179

ISBN: 978-989-758-114-4

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

related to the terms, the involved actors, the objects

to be certified and the requirements against which

the objects should be certified.

2.1.1 Basic Concepts

According to the related ISO (ISO/IEC Guide 2,

1996), the certification is: “a procedure by which a

third party gives written assurance that a product,

process or service conforms to specified

requirements”. Such “assurance” can be given as a

result of an activity, namely “conformity

assessment”, defined in the same Guide but

perfected by the standard (ISO/IEC DIS 17000,

2004) as follows: “an activity that provides

demonstration that specified requirements relating

to a product, process, system, person or body are

fulfilled”.

Notice that nothing such as a guarantee is

desired. Usually the intended demonstration

represents the “confidence” (not the “proof”) that the

requirements have been fulfilled: certification cannot

give a guarantee, but can only increment the

confidence on the certification target objects.

2.1.2 Actors, Requirements and Objects of

the Certification

The most important involved actors are the

certification body and the accreditation body.

A certification body is an organism with internal

rules, human/infrastructure resource and skill to

perform certification procedures. To make the

results of certification comparable and then get

broad consensus about, the internal rules themselves

might be required to be conformant to defined

standards. In such a case, certification bodies can be

“accredited” that is, declared capable of performing

certification, upon periodical surveillance, by special

organisms called accreditation bodies. This is

compatible with the above definition of conformity

assessment.

Strictly speaking, a certification body does not need

to be accredited, but the accreditation is important to

increase the value of the certification, and then the

value of the certified object. Currently the

accreditation bodies are not so many (average is

one-two per country, against tens or hundreds of

certification bodies, generally specialized per

product category), so they can accredit each other by

executing periodical conformity assessments as

“peer reviews” upon their activities.

Other actors involved in certification are those who

want to give confidence on the object of certification

(over certification and accreditation bodies also

suppliers, sellers, standard makers…) and who want

to get confidence on the object of certification

(customers, users, end users, government…).

Therefore entities and relationships among different

actors can vary depending on wanted consensus

about their acts and on other opportunities.

Requirements, as mentioned in the definitions given

for certification, may be expressed in terms of

standards or legislation. Again, this is aimed at

increasing confidence on certification, since

standards are designed to be commonly accepted

reference models, allowing certification bodies to

express comparable and repeatable results. This in

turn facilitates, at least in principle, circulation of

goods, and fosters commercial co-operations with

mutual acceptance of the results of certification in

the international trading framework.

The objects of certification are usually processes,

products, people or organizations. To be more

precise, as a measure is a statement of an attribute of

an object, certification often refers to properties or

attributes of objects: so, there is certification of

attributes (e.g. electrical properties) of a product, of

attributes (e.g. capability) of a process, of skill of

professionals, of quality systems of organizations.

In order to assess conformity in a repeatable and

documented way, a certification body must follow a

defined process, and it is important that all the

certification bodies follow the same rules for the

same object types. Again, widely recognized

standards for the assessing process would give such

a confidence.

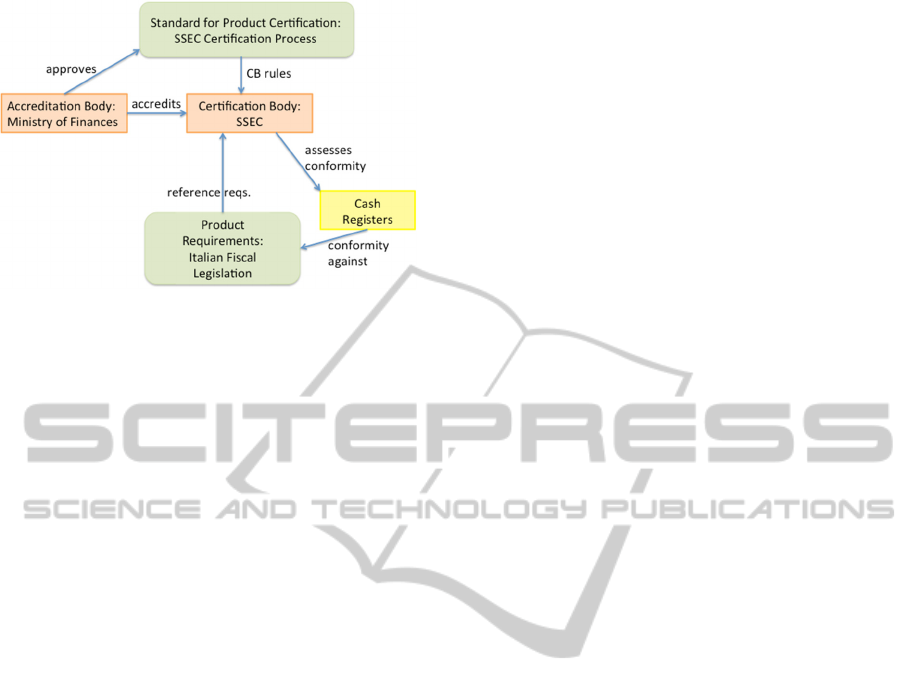

With respect to the general certification scenario

discussed above, the activities performed at the

SSEC has got some peculiarities:

• The role of Accreditation Body in the case of the

Fiscal Meters certification is played by the Ministry

of Finances. It appoints the certification bodies and

performs a sort of control on their certification

activities. No standards for the accreditation are

used. In addition the Ministry of Finances doesn’t

ask nor provide any mutual accreditation/recognition

with respect other peer accreditation bodies.

• A certification centre, here identified by the SSEC,

plays the role of Certification Body. The SSEC

certification process is approved by the

Accreditation Body (Ministry of Finances) and the

Italian Fiscal Legislation plays the role of Standard

for Product Requirements. The resulting

Certification and Accreditation scenario for the

Fiscal Meters Certification is represented in Fig. 1.

CertificationandLegislation-AnItalianExperienceofFiscalSoftwareCertification

175

Figure 1: SSEC Certification and Accreditation scenario.

2.2 Cash Register Certification

In order to simplify the tax relations between Eu-

ropean Community member countries, in 1972 Italy

has adjusted its tax policies to the other countries tax

policies introducing the value added tax (V.A.T.)

(D.P.R. 633, 1972). By V.A.T. introduction, a sup-

plier of goods or services must charge to the

customer the payment of a tribute, and in turn the

supplier must pay that tribute to the Government.

Subsequently to the V.A.T. introduction, it was

necessary to monitor the revenues of the commercial

activities in order to check the regularity of their

transactions in terms of data integrity and security.

The phenomenon of the tax evasion quickly

increased, and the fiscal receipt was considered the

instrument to oppose the tax evasion. Therefore the

law (L. 18, 1983) established the duty for the cash

register of issuing a fiscal receipt, at the time of the

payment, for the sale of goods, not subject to the

emission of an invoice and occurring in shops or

open public places.

The cash register must be compliant with the

model and the characteristics defined by the

Ministry of Finances (D.M. 03/23, 1983) and its

certification is mandatory before the cash register is

marketed. To this aim, by further laws and decrees

(D.M. 19/06, 1984), (D.M. 14/01, 1985), (D.L. 326,

1987), (D.M. 4/04, 1990), (D.M. 30/03, 1992),

(D.M. 04/03, 2002), (P.M. 31/05, 2002), (P.M.

28/07, 2003), (P.M. 16/05, 2005) the Ministry of

Finances established modalities and terms for the

release of cash registers. According to the current

Italian legislation the cash register definition

includes:

What It Is: The cash registers are devices designed

to record and process numerical data entered by the

keyboard or other suitable functional unit of

information acquisition, equipped with the device to

print on special supports the same data, and their

total (D.M. 03/23 all. A, 1983)

Why It was Introduced: As reported above, the

cash registers were introduced for the release of the

fiscal receipt that was considered the instrument for

checking the regularity of the economic transactions.

By the fiscal receipt it is possible to keep trace of the

payments and therefore to monitor the revenues of

the commercial activities. Consequently, the cash

register must satisfy some requirements of security

and, in particular, of integrity in order to prevent

“unauthorized access to, or modification of,

computer programs or data” (ISO/IEC 25010, 2011).

Its Components: The cash register is composed of

indicating devices (tipically screens), a printing

device, a fiscal memory and the casing. Each

component must satisfy specific normative

requirements. In particular the indicating devices

must be two and the displayed characters must be at

least seven millimeters high. The devices must be

placed on the two opposite sides of the cash register

in order to allow to the purchaser an easy reading of

the displayed amounts.

The printing device provides for the release of the

fiscal receipt, daily fiscal closing report and of the

electronic transactions register. Printed characters

must be at least twenty-five millimeters high.

The fiscal memory is an immovable affixed memory

that contains fiscal data. It must record and store the

fiscal logotype, the serial number, the progressive

accumulation of the amount, etc. In order to

guarantee the integrity of its data, the fiscal memory

must allow, without the possibility of cancellation,

only progressive increasing accumulations and the

preservation of their contents over time.

Finally the casing must foresee a unique fiscal seal

by means of a single screw that ensures the

inaccessibility of all hardware components involved

in the fiscal functionalities of the cash register,

except for the paper management. Also, onto the

casing, must be applied in a well visible place on the

front toward the buyer, a slab with reported data as

mark of the manufacturer, machine serial number,

data of the model approval document and the service

center.

What Kind of Documents It Must Issue: The cash

registers have to be able to print a fiscal receipt, a

daily fiscal closing report, and an electronic

transactions register. Each document must contain

mandatory information specified for single

indention, for instance: company name, owner name

and surname, V.A.T. percentage and company

address, accounting data, etc. The Italian legislation

detailes these generic descriptions providing

ICSOFT-EA2015-10thInternationalConferenceonSoftwareEngineeringandApplications

176

hardware and software requirements that better

characterize structure and functionalities of a valid

cash register (D.M. 03/23 all. A, 1983). In particular

the legislation requires two separate certification

processes: one for the hardware components and one

for the software layer. The two processes are quite

similar in the steps to be performed and differentiate

mainly on the kind of test cases to be applied. For

instance for the hardware components tests for water

tightness or battery capacity as well as HW

reliability are required, while for the software

components black-box tests defined on the basis of

legislation requirements are executed.

The certification of a cash register needs that

both the processes terminate with successful results.

For aim of simplicity this paper only details the steps

required for the fiscal software certification.

2.3 Cash Register Software

Requirements

From the ministerial decree (D.M. 03/23, 1983) on,

the Italian legislation disciplined different moments

of the cash register industrial life-cycle and imposed

precise technological constraints. In order to

highlights the level of detail adopted for the

requirements specification in the Italian legislation

in this section some examples are provided. The

complete requirements list can be extracted from the

legislation.

During the Data Input, it must Not be Possible:

1) To change time in wrong formats (e.g. 26:44).

2) To change date in wrong formats (e.g.

31/09/2012).

With exhausted Fiscal Memory:

The command of issuing a fiscal receipt must

not be executed.

If the Printing Device is disconnected:

1) Any issuing of fiscal documents by the cash

register must be inhibited

2) Congruent warnings must be reported.

3 SSEC EXPERIENCE

The SSEC of the National Research Council

performs third-party evaluations and certifications of

software processes and products, according to

national legislation and international Standards to

meet the needs of users, suppliers and public

administration.

In detail, for the cash registers, the SSEC activities

are: software and hardware certification according to

Italian fiscal legislation on behalf of the Italian

Ministry of Finances, and systems evaluation

(Reliability prediction, Safety, MTBF of context-

dependent systems, Compliance against standards).

In particular the certification process adopted inside

the SSEC is divided into two separate phases (Pezzè

and Young, 2008): the off-line testing activity

preparation and the on-line testing session.

In the context of the fiscal software certification, the

SSEC has also set an activity of building up a

database of data collected by the certifications

already performed in order to set up and conduct

empirical research studies. These data could be of

interest for other certification bodies or involved

actors. Collected data are focused on software

characteristics like maintainability and reliability of

the fiscal software or security of the fiscal data, etc.

The collected data are, for instance, Mean Time

Betweeen Failure (MTBF) or fault patterns and

redundancy as reliability measures, or also number

of provided authentication methods and number of

data corruption instances actually occurring as

security measures.

The data collection is an important and

continuous work in progress of the SSEC due to the

numerous normative updatings and technological

innovations that have deeply modified the product to

be certified over the years. Continuous changes in

the database inputs raise problems of data uniformity

and make difficult having long terms statistical

analysis. Nevertheless the database promotes an

approach of improvement and building up of best

practices for the fiscal software certification.

3.1 Off-line Testing Activity

During the off-line testing activity the collection of

the different information relative to the development

process of the cash register is performed. In

particular five kind of sources are considered:

1) Documentation, that is the collection of

documents provided by the cash register developers.

It mainly consists in: an architectural model, i.e. the

description of the hardware and software

components of the cash register; a functional model,

i.e. the specification of functionalities implemented

in the source code; an end user manuals: the

description of the interface and the functionalities

available to the final user. The documentation

includes the maintenance procedures necessary

during the cycle life of cash register;

2) Additional Information, or extra data that can be

requested as completion of the mandatory

documentation.

CertificationandLegislation-AnItalianExperienceofFiscalSoftwareCertification

177

3) Source Code, i.e. the source code of the cash

register completed with the libraries that could be

used during the on-line testing activity.

4) Requirements Repository, i.e. the collection of

cash register requirements, both form the hardware

and software point of view, as required by the Italian

legislation.

5) Test Case Database, that is the collection of test

cases and corresponding correct results useful for the

evaluating of the cash register during the on-line

testing session. In particular a set of specific test

cases and responses is associated to each of the

requirements collected in the requirements lists.

3.2 On-line Testing Activity

During the on-line testing activity the documentation

collected in the off-line activity is exploited for the

conformity assessment of the cash register. In

particular inside the SSEC group the activities can

be divided into the following steps (Pezzè and

Young, 2008):

1. Documentation Analysis: the information

contained into the “Documentations and Additional

Information” folders are analyzed in order to iden-

tify characteristics and functionalities implemented

into the cash register under certification.

2. Requirements Selection: on the bases of the

architectural and functional models, the susbsets of

hardware and software requirements are identified

from the complete list of requirements available into

the “Requirements Repository”.

3. Test Objective Selection: For each of the

selected requirement subsets, the test objectives are

identified. In particular the SSEC considers five

different testing conditions corresponding to

different cash register behaviors: Initialization, i.e.

the fiscal memory of the cash register is not

recording data (fiscal memory not jet active); Fiscal

Functioning, i.e. the fiscal memory is activated;

Abnormal Conditions, i.e. possible anomalous

behavior due to misinterpretation or incorrect time

and data input; Boundary Condition, i.e. boundary

values for the fiscal memory use are considered, for

example close to the exhaustion or exhausted;

Malfunctioning, i.e. accidental and malicious

situations are considered.

4. Test Plan Definition: According to the detected

test objectives for any requirement subsets, one or

more test cases are selected among those available

into the Test Cases Database. In case of the test

cases are missing the proper ones are ad-hoc

generated and the Test Case Database enriched

accordingly. In this way a customized test plan is

obtained.

5. Test Plan Execution: The required test

environment is set up and the selected test cases are

executed. During this phase the test results are

collected and compared with the correct results

associated to each of the executed test case. If the

expected result is the same of that obtained by the

cash register, then the test case is considered as pass,

otherwise the test case is classified as fail. At the end

of the testing session, the set of verdicts (pass or fail)

are collected into a Test Report. In case of error

discovered during the test execution a modification

of the source code is requested to the cash register

developers and an optional phase of regression

(Pezze` and Young, 2008) testing is considered.

6. Certification Results: The final product of the

certification process is the Compliance Certificate,

that is the collection of the provided documentation,

by the test report and by the certification center

possible remarks and comments. It is to be noticed

that the certificate can be only successful. In case the

testing step has failed, a report of any spotted issues

is drawn up both to lead the stakeholder during its

software improvement and to update the certification

centre activity historical recording. After the

stakeholder may apply again to a new testing

session.

4 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

In the previous sections the overall certification

process adopted inside the SSEC has been presented

and the off-line and on-line testing activities,

performed during the process, have been detailed.

However, due to the peculiarities of each cash

register, to the company that develops it and to the

Italian legislation, many exceptions to the presented

process have been encountered over the years. In the

following a not exhaustive list of the main challen-

ges derived by the everyday experience is discussed.

The first one is represented by the Italian legislation.

It tends to be too verbose and too generic to cover all

the possible exceptions and issues. This can cause

misunderstanding and errors during the assessment

of the requirements satisfaction. The automation of

the conformance assessment process would be a

desirable goal, but a too generic and continuously

modified legislation is a strong limit to this

automation, and the human intervention is thus

always necessary. Besides, the SSEC keeps

continuously updated and aligned the Requirements

ICSOFT-EA2015-10thInternationalConferenceonSoftwareEngineeringandApplications

178

Repository to the continuous modifications in the

legislation imposed by the designate authorities.

However these modifications heavily influence also

the historical data collection, its uniformity and

analysis. An additional challenge of the SSEC

activity is therefore to adopt specific procedures to

manage, verify and update the normative corpus so

promptly react and integrate the legislation

modifications, the official clarifications or

interpretations provided by the designate authorities.

During the on-line testing activity one of the main

problem encountered by the SSEC has been the

management of the documentations provided by the

stakeholders that in many cases did not reach the

sufficient level of detail. Indeed, due to time-to-

market constraints, either the architectural model or

the functional model could not be fully complete and

documentation integration could be necessary.

An additional critical issue of the on-line testing

activity is the management of the errors discovered

during the test plan execution. Indeed, in case of

faults or non-compliances, corrections of the source

code are necessary. This increases the prize, in terms

of time and effort, of the certification and

development activities. In particular, an important

delay in the test certification release could be caused

by the necessity to the execution of an additional

phase of regression testing. This is important to

verify that the source code corrections do not

invalidate the already tested functionalities. To

speed up this part of the process, the solution

adopted inside the SSEC is the compartmentation of

the source code, i.e. wherever possible, by the

analysis of the documentation available, the source

code is sliced into separate components so that only

the test cases related to a specific part are selected

and re-executed.

In order to identify the best strategy to improve

the effectiveness of the fight against tax evasion,

currently the Italian legislators are trying to

strengthen the transactions traceability. To this aim,

the abolition of the fiscal receipt is being considered

as well as the adoption of tools for the electronic

invoice and the telematic transmission of the

payments. By means of these actions, an important

process of cultural change is becoming established

in the country. This apparent simplification of the

transactions traceability imposes new challenges of

technological advancement and adjustments in

respect of the legislation for the cash register

developers, suppliers and vendors. A reorganization

of the certification process in the legislation

compliance check is needed as well. These

challenges advise that the fiscal receipt is more and

more becoming the symbol of a historic moment

destined already to a quick end (Prokin and Prokin,

2013).

REFERENCES

Brocke, J. V. and Rosemann, M., 2014. Handbook on

business process management 1: Introduction,

methods and information systems. Springer, Berlin,

Germany.

D.L. 326, 1987. Decreto Legge 4 Agosto 1987, n. 326.

(Italian legislation, in Italian).

D.M. 03/23, 1983. Decreto Ministeriale 23 Marzo 1983.

(Italian legislation, in Italian).

D.M. 03/23 all. A,1983. Decreto Ministeriale 23 Marzo

1983, allegato A. (Italian legislation, in Italian).

D.M. 04/03, 2002. Decreto Ministeriale 04 Marzo 2002.

(Italian legislation, in Italian).

D.M. 14/01, 1985. Decreto Ministeriale 14 Gennaio

1985.(Italian legislation, in Italian).

D.M. 19/06, 1984. Decreto Ministeriale 19 Giugno 1984.

(Italian legislation, in Italian).

D.M. 30/03, 1992. Decreto Ministeriale 30 Marzo

1992.(Italian legislation, in Italian).

D.M. 4/04, 1990. Decreto Ministeriale 4 Aprile 1990.

(Italian legislation, in Italian).

D.P.R. 633, 1972. Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica

26 Ottobre 1972, n. 633 (Italian legislation, in Italian).

ISO/IEC DIS 17000, 2004. Conformity assessment -

Vocabulary and general principles.

ISO/IEC FDIS 25000, 2005. Systems and software

engineering - Systems and software Quality

Requirements and Evaluation (SQuaRE).

ISO/IEC FDIS 25010, 2011. Systems and software

engineering - (SQuaRE)- System and software quality

models.

ISO/IEC Guide 2, 1996. Standardization and related

activities – General vocabulary.

L. 18, 1983. Legge 23 Marzo 1983, n. 18. (Italian

legislation, in Italian).

Pezzè, M. and Young, M., 2008. Software testing and

analysis: process, principles, and techniques. John

Wiley & Sons.

P.M. 16/05, 2005. Provvedimento Ministeriale 16 maggio

2005. (Italian legislation, in Italian).

P.M. 28/07, 2003. Provvedimento Ministeriale 28 Luglio

2003. (Italian legislation, in Italian).

P.M. 31/05, 2002. Provvedimento Ministeriale 31 Maggio

2002. (Italian legislation, in Italian).

Prokin, M. and Prokin, D., 2013. Gprs terminals for

reading fiscal registers. In Embedded Computing

(MECO), 2013 2nd Mediterranean Conference on,

pages 259– 262. IEEE.

CertificationandLegislation-AnItalianExperienceofFiscalSoftwareCertification

179