Visualizing Cultural Digital Resources using Social Network Analysis

Antonio Capodieci

1

, Daniele D’Aprile

1

, Gianluca Elia

1

, Francesca Grippa

2

and Luca Mainetti

1

1

University of Salento, Via per Monteroni snc, Lecce, Italy

2

Northeastern University, 360 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA, U.S.A.

Keywords: Information Extraction, Information Gathering, Cultural Heritage Objects, Real-Time Data Extraction,

Social Network Analysis.

Abstract: This paper describes the design and implementation of a prototype to extract, collect and visually analyse

cultural digital resources using social network analysis empowered with semantic features. An initial

experiment involved the collection and visualization of connections between cultural digital resources - and

their providers - stored in the platform DiCet (an Italian Living Lab centred on Cultural Heritage and

Technology). This step helped to identify the most appropriate relational data model to use for the social

network visualization phase. We then run a second experiment using a web application designed to extract

relevant data from the platform Europeana.eu. The actors in our two-mode networks are Cultural Heritage

Objects (CHOs) shared by institutional and individual providers, such as galleries, museums, individual

experts and content aggregators. The links connecting nodes represent the digital resources associated to the

CHOs. The application of the prototype offers insights on the most prominent providers, digital resources

and cultural objects over time. Through the application of semantic analysis, we were also able to identify

the most used words and the related sentiment associated to them.

1 INTRODUCTION

The role of social media in distributing travel-related

information can no longer be ignored by tourism

marketers. Involving the crowd allows managers and

policy makers to identify potential customers’ needs

and, via participatory activities, to interact and retain

those members of the crowd who are mostly

interested in visiting particular points of interest

(Miguens et al, 2008). More and more, user-

generated content is complementing traditional

sources of information, creating an unexpected

competition among service providers such as travel

agencies, travel guides, or territorial development

agencies. Online social travel networking is

changing the way tourists plan their trips.

Crowdsourcing websites such as Triptease, Find My

Itin, Stackla, Gogobot, Geeks on a Plane, offer users

an interactive and visual experience to plan a trip

based on what peers suggest.

Collecting and recombining this ever-changing

knowledge base created by customers, suppliers, or

the general public, is facilitated by the creation of

informal communities that share common interests,

learn, interact and collaborate towards common

goals. In the context of creating and nurturing these

informal communities, social networking platforms

enable the creation of relationships with important

stakeholders. The biggest value of social networking

sites is represented by their ability to act as channels

to foster collaboration and innovation. Social

networks play now a key role in planning strategies

to engage communities within and outside the

organizational boundaries, recruit employees with

the right skill-set, and develop innovative ideas.

The goal of our research is to design and test a

prototype to extract, collect and visually analyse

cultural digital resources using social network

analysis (SNA), empowered with semantic features.

The research questions leading our study are: How

to identify the most active providers of digital

resources in an online platform? How positive or

negative is the content shared by these providers to

illustrate a cultural resource? What types of cultural

resources are exchanged by online communities

during a specific timeframe? Which is the historical

period that attracted most of the attention within an

online community sharing digital cultural resources?

The experiment we describe in this paper

provides a valuable perspective on the evolving

186

Capodieci, A., D’Aprile, D., Elia, G., Grippa, F. and Mainetti, L..

Visualizing Cultural Digital Resources using Social Network Analysis.

In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2015) - Volume 1: KDIR, pages 186-194

ISBN: 978-989-758-158-8

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

interests of online communities towards cultural

heritage. Our research relies on the results of DiCet,

an Italian research project which sets the ground of a

Living Lab focused on Culture Heritage and

Technology. The DiCet project defines and

implements models, processes and ICT tools for

sustainable development of an intelligent territory

through the exploitation of its cultural heritage and

environmental resources. The project adopts the

Future Internet paradigm and social networking

techniques to realize an ecosystem of cooperating

heterogeneous entities such as companies,

government, citizens and tourists. DiCeT aims to

define and develop an open enabling platform of

intelligent services for cultural heritage

capitalization, able to enhance cultural experience by

leveraging on social inclusion, interaction and

augmented reality. The project aims to build

innovative services for improving the knowledge

shared by tourists, citizens, operators, and

researchers, as well as the cultural heritage fruition,

its conservation and preservation. The project

benefits from a multi-stakeholder partnership

composed of Italian universities, private companies

and research centres (i.e. University of Salento,

IBAM CNR Engineering Ingegneria Informatica

SpA, Open 1, Expert System, etc.).

DiCet leverages the federated architecture of

Europeana, the largest European digital library

(http://www.europeana.eu), which allows to flexibly

manage cultural content in the cloud. In the context

of the emerging Internet of Things (Xia et al., 2012),

Europeana represents an important effort to link

cultural heritage objects (CHOs) and their metadata

across several cultural institutions. This has the

potential to provide policy makers, researchers and

tourists with the opportunity to explore cultural

heritage in a more enriched way.

Europeana connects more than 2,000 European

institutions, from regional archives to local

museums. These providers contribute to feed this

open library with digital objects, thus sharing

cultural and scientific heritage items from prehistory

to modern era. Europeana introduces the Europeana

Semantic Elements, a common standard to facilitate

information retrieval of cultural items at European

level. The Europeana Data Model introduces a richer

metadata standard that helps users to receive more

and better quality digital content. Despite the recent

interest in capturing data on the creation of cultural

digital resources, there seem to be still issues

concerning the quality and quantity of the

information found in the descriptive metadata

associated with the digital representations of cultural

heritage objects (Beaudoin, 2012). This information

is often considered inadequate to make sure users

understand the nature of the cultural object and its

digital representation (Tsirliganis et al., 2004). The

goal of developing a web application to collect data

from Europeana is to analyse how different

providers (e.g. galleries, foundations, individual

experts) interact, co-create knowledge, and share

cultural digital resources.

Our quasi-experimental design (Shadish et al.,

2002) involved collecting insights to address the

issues of metadata interoperability within DiCeT,

thus designing a “Semantic Enterprise Service Bus

for Cultural Heritage” to access data and information

coming from multiple data sources. The service bus

uses an ontology-based approach to integrate

different and heterogeneous data sources (Wache et

al. 2001; Gawinecki, 2008; Shi et al. 2014; Zhu

2012). We first run a pilot experiment with all the

data stored in the DiCet platform in order to

visualize and measure the structure, content and

sentiment of social communication networks by

using the software suite Condor. Then, we built a

web application to collect data from the Europeana

portal, and process cultural objects using the same

approach and methodology. To this purpose, we

selected a sample of cultural objects to demonstrate

the potential of the web application.

2 SOCIAL NETWORK ANALYSIS

IN THE TOURISM INDUSTRY

An important aspect of social media applications is

the wealth of user generated content. This can prove

highly beneficial in directing tourists’ choices, and

can be of extreme value for the understanding of

market preferences and needs. New opportunities for

research are now available considering the growing

online connectivity of individuals, as well as the

development of APIs allowing more directed data

collection (Miguéns et al., 2008; Schoder et al.,

2013). Recent experiments are proposing new

systems to build new type of communities based on

physical proximity. Pietilainen et al. (2009) designed

and implemented a mobile social networking

middleware named “MobiClique” that creates and

exploits ad hoc social networks to disseminate

content using a “store-carry-forward technique”.

SNA techniques and tools have been demonstrated

to be useful to dynamically assess the value created

by social interactions. Some of the most commonly

used metrics of social network include indicators of

Visualizing Cultural Digital Resources using Social Network Analysis

187

individual prominence such as contribution index,

closeness and betweenness centrality, as well as

group level indicators like density, group degree or

betweenness centrality (Borgatti and Everett, 2006).

Researchers have been analysing social networks

by mining e-mails, forum posts, mailing list

archives, hyperlink structure of homepages, or co-

occurrence of text in documents (Erétéo et al.,

2008). Social Network Analysis offers a well-

established set of tools and techniques to monitor the

emergence of social interactions (Wasserman and

Faust, 1994). By mapping social networks of online

users and the content they exchange it is possible to

recognize emerging communities based on specific

aggregation criteria, such as virtual and physical

proximity, data sharing, or access to common

services. It is also possible to monitor how

preferences and needs change over time and locate

the community members with high betweenness

centrality or degree centrality (Wasserman and

Faust, 1994), who have the potential to provide

access to a large number of members with similar

needs, preferences or skills.

Despite the interest in adopting a network

approach to study interactions in the tourism

industry (Tonti and Baggio, 2012), there is still a

lack of empirical research on the benefits of

monitoring the evolution of networks of people

interacting on social media with a touristic vocation.

D’Agata, Gozzo and Tomaselli (2012) employed

measures derived from Social Network Analysis to

create territorial networks. The authors used survey

data from a sample of tourists leaving from airports

and ports of the main cities in Sicily (Italy). Despite

the interesting results, the work still relies on

traditional approaches, such as surveys and

questionnaires, to understand how people and places

interact with each other. In our research we use data

shared directly by users on a platform. Digitally-

enabled SNA affords relatively unobtrusive and

objective measurement of interaction behaviours of

individuals and groups. By observing their evolution

in terms of structural properties (e.g. degree

centrality, density) as well as content creation, it is

possible to recognize how positive and negative

opinions are disseminated and how they influence

people in the context of online communities. Given

the importance of collaborative relationships to act

as critical channels for knowledge search, transfer

and creation, policy makers and cultural institutions

might benefit from developing networks with other

users that may represent valuable sources of

knowledge.

3 A NETWORK APPROACH TO

VISUALIZE CULTURAL

RESOURCES

In this study, we combine SNA with semantic

analysis to overcome the intrinsic limitation of

traditional SNA studies that consider all the ties in a

network as homogeneous in content. Content

analysis and other text analytics techniques are

complementary research methods useful to make

inferences from texts about the context of their use.

Campbell and Pennebaker (2003) have

implemented a probabilistic computational system

called Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (aka

LIWC) that counts all the words in a body of text

and classifies each word as belonging to one or more

“dictionaries”, including positive and negative

words. Gloor et al. (2009) have used a bag-of-words

approach similar to LIWC. The bag-of-words model

is a simplifying representation used in natural

language processing. In this model, text such as an

e-mail or a forum post is represented as an

unordered collection of words, disregarding

grammar and overall meaning. Gloor et al. (2009)

have classified and counted the number of words in

each actor’s email communication that reflects

positive or negative emotion, or the use of an ego

word, and then aggregated individuals’ data to the

team level. Zhang et al. (2013) used sentiment

analysis to assess teams using dynamic SNA.

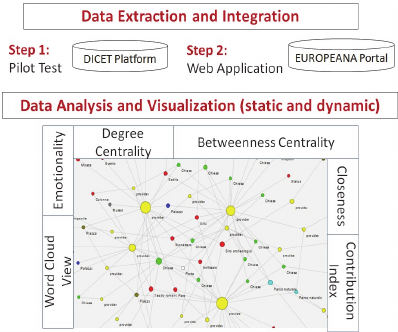

Figure 1 describes the methodology we followed

to extract data initially from the DiCet platform, and

then from the Europeana portal. In order to visualize

and analyse the relational data, we selected social

network metrics and semantic indicators to represent

both structural properties of social networks, and the

semantic associated to each object.

Figure 1: Steps of the methodology.

KDIR 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval

188

Specifically, we used actor betweenness

centrality, actor degree centrality, density and word

usage, which offered meaningful insights to address

our research questions. Betweenness centrality is

calculated as the fraction of shortest paths between

every possible pair of nodes that pass through at

least one node in the group (Wasserman and Faust,

1994). Actor degree centrality is the total number of

other points to which a point is adjacent. We also

looked at density of the graphs, calculated as the

total number of ties divided by the total number of

possible relational ties (Wasserman and Faust, 1994;

Borgatti and Everett, 2006). We finally looked at the

sentiment conveyed by the providers in describing

the cultural heritage objects (CHO). Sentiment is a

measure with a value between 0 and 1, where 0

indicates that the message is very negative and 1

very positive (Brönnimann, 2014, Pang et al., 2002).

Sentiment of the message is calculated from a

specially developed multi-lingual classifier based on

a machine learning method with data coming from

Twitter. In this study we calculate positive and

negative sentiment in the comment left by users

using a simple “bag-of-words” approach (Whitelaw

et al., 2005), employing user-generated mood word

lists relevant for the domain area. This approach has

been developed initially looking at large e-mail

archives (Gloor et al., 2009). For each e-mail,

“emotional words” matching a pre-loaded list were

counted and then normalized by the total number of

words in each message (Brönnimann, 2014).

Following this approach, each e-mail or any other

text is assigned with a positivity value and a

negativity value ranging from 0 to 1.

Another metric of sentiment analysis that we

used in this research is the “word usage over time”

based on the most frequently used term saved by the

providers to describe CHO and its digital resources

(Gloor et al., 2009).

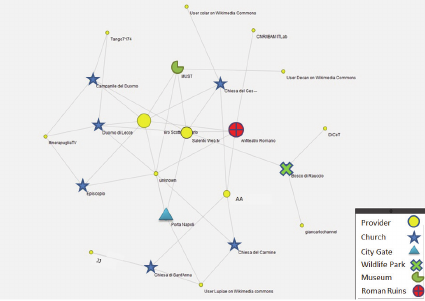

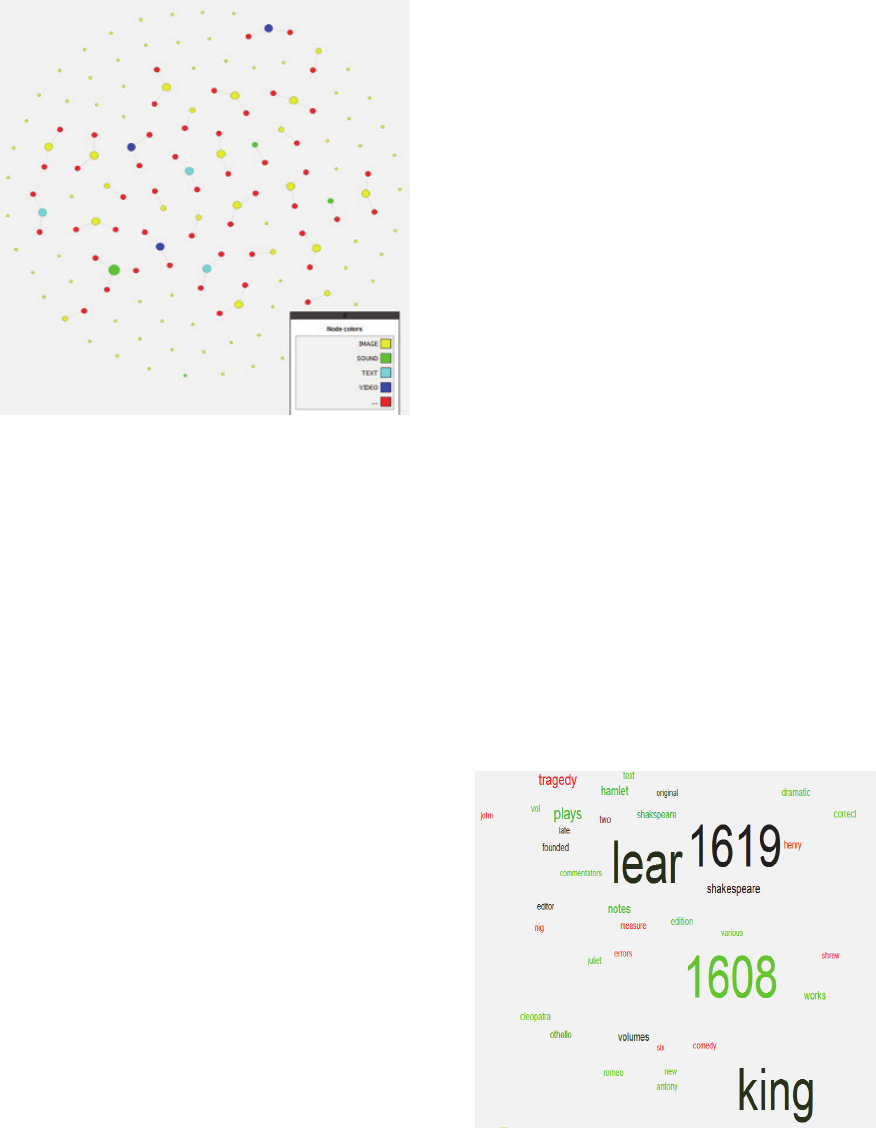

Figure 2: Visual Maps of users and points of interest.

There are a few software packages that can deal

simultaneously with several sources of data and

combine them in a way that is easily available for

visualization to final users. In this study we used the

software program Condor, which allows to visualize

and measure the structure, content and sentiment of

social communication networks over time. Condor

creates static maps and movies of relationships that

can come from social networks, web site link

structures, and concept maps of unstructured

documents, online forums, phone archives, or e-mail

networks.

4 BUILDING THE PROTOTYPE

4.1 Pilot Test with the DiCet Platform

In this study, a provider is a generic entity that can

provide content to the platform. A provider can be a

museum, a cultural expert, or a tourist. In that sense,

it will be treated either as a string of text or as an

URL. Figure 2 illustrates an example of a two-mode

network where nodes represent both the digital

contents and points of interest (resources), and the

individuals or organizations uploading them into the

system (providers). Definitely, two mode networks

are characterized by actors who belong to two

different sets (Wasserman and Faust, p. 29) that are

providers or resources.

In the sociogram shown in Figure 2 the size of

the node represents the betweenness centrality,

which offers initial insights on the most active

contributors in the DiCet platform. Bigger nodes

represent resources or providers that connect more

resources/providers who would not be otherwise

connected (Wasserman and Faust, 1994). In other

words, the size of the node represents the most

active users/data providers, or the most talked about

and discussed resources. For example, by looking at

Figure 2, the Roman Ruins and the city Wildlife

Park were the points of interest that mostly attracted

the attention of users who posted more photos or

more comments about them.

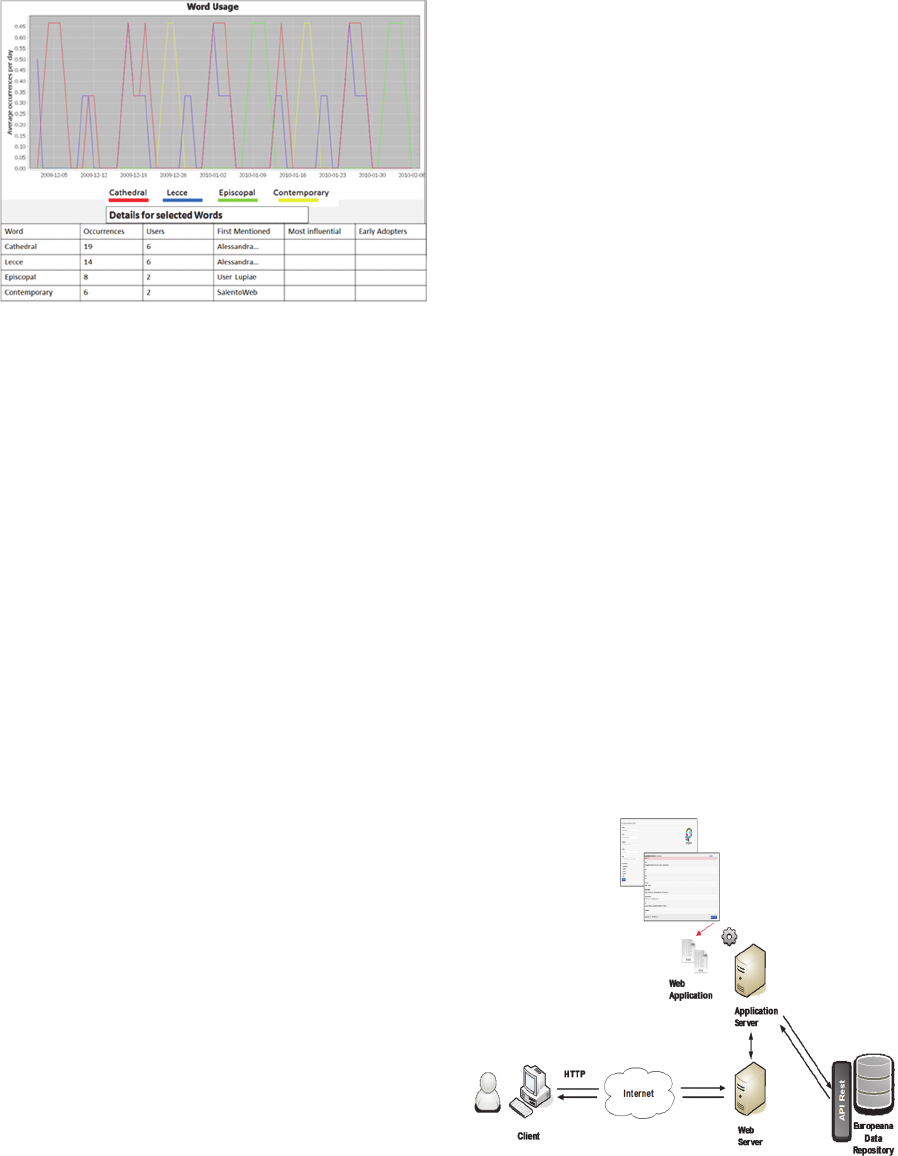

Figure 3 illustrates the evolution over time of

words used by providers of digital resources in order

to describe points of interest. The graph identifies

the words that were most frequently used every day

by the users of the DiCet platform. It also detects

who was the first provider to use that word and

when this occurred. This representation used a Bag-

of-Word approach (Gloor et al., 2009) to calculate

the word usage and offer some insights about the

extent of language complexity used to describe the

Visualizing Cultural Digital Resources using Social Network Analysis

189

Figure 3: Word Usage (DiCet platform) – hypothetical

timeframe.

digital resources/points of interest. Looking at

indicators such as “deviation of word usage”, we can

determine how complex or essential the

communication is and we can observe new ideas

being generated over time. In the example presented

in Figure 3, we were able to identify the most

popular concepts over time, based on their

occurrences. For instance, “cathedral” and “Lecce”

were the most talked about terms (19 and 16

occurrences) and the user “Alessandra A.” was the

one to introduce those concepts for the first time.

The sentiment classifier used in the Condor

software is able to determine positive, negative or

neutral sentiment of documents in various

languages, though the most reliable results are still

based on the use of English words. The sentiment

classifier is currently in a training phase for the

Italian language. This is the reason why we did not

conduct a complete sentiment analysis for the DiCet

posts. Nevertheless, we were able to identify the

most frequently used words over time (see Figure 3).

The next sections illustrate how we used the

insights from the DiCet pilot test to build an

application that can extract data from the portal

Europeana.eu.

4.2 Development of the Europeana

Web Application

Europeana.eu is an Internet portal that acts as an

interface to millions of books, paintings, films,

museum objects and archival records that have been

digitised throughout Europe. Mona Lisa by

Leonardo da Vinci, Girl with a Pearl Earring by

Johannes Vermeer, the works of Charles Darwin and

Isaac Newton, and the music of Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart are some of the highlights on Europeana.

Europeana gives access to different types of content

from different types of heritage institutions. The

digital objects that users can find in Europeana are

not stored on a central computer, but remain with the

cultural institution and are hosted on their networks.

Europeana collects contextual information – or

metadata – about the items, including a small

picture. Users can search this contextual information

and, once they find what they are looking for, they

can access the full content of the item by clicking

through the original remote site that holds the

content.

The Europeana portal is used to search and

browse a public repository which contains many

objects of various types including books, audio and

video objects, photos, paintings, etc. These objects

are collected from different domains, including

fashion, natural history, archaeology, history, art,

and so on. Users can narrow their search and filter

by titles, creators, subjects, dates/periods, or places.

Alternatively, they can type the words “who”,

“what”, “where” or “when” into the Europeana

search box followed by a colon.

The web application we developed provides the

same search and filtering functionalities as the

Europeana portal, presenting the results in a human

friendly representation (html). It has been

implemented in order to facilitate access to

Europeana Metadata by remote invocation of

Europeana Search API when using the Java

programming language. This was developed by

using the Europeana4J source code which provides

a comprehensive set of features for interacting with

the HTTP / REST-based Europeana API. It also

exports the search results in CSV format, which is

commonly accepted for SNA tools.

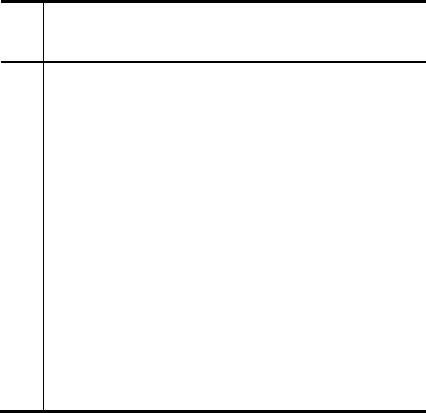

Figure 4: System architecture overview.

Figure 4 provides an overview of the system

architecture that highlights the two main

KDIR 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval

190

components: the web application and the Europeana

metadata repository. The Europeana REST API

allows to build applications that use the wealth of

cultural heritage objects stored in the Europeana

repository. The API uses the standard web

technology of REST calls over HTTP. Responses

are returned in the popular JSON format. The users

of this web application typically use an Internet

browser to retrieve and visualize the Europeana

objects. After performing a search, our application

allows to export the results in .CSV format, in order

to feed the social network analysis tool and proceed

with data analysis and visualization.

4.2.1 Class Diagram

The web application implementation is based on the

main classes of the Europeana4J framework and on

some specific classes that allow users to export

results in CSV format. For example the classes

EuropeanaConnection and EuropeanaApi2Client

implement the querying of the Europeana API,

making use of the HttpConnector class, which

facilitates reliable communication over the http

protocol.

The class EuropeanaApi2Results deserializes the

message in the response returned by the Europeana

server and provides the Europeana objects. The

SearchAction class handles the parsing of Europeana

JSON metadata text documents and the creation of

internal Java objects. Finally, the ExportAction class

uses handy methods belong to CreateCSVFile class

to write results into CSV files.

4.2.2 Network Visualization of Europeana

Data

Using data extracted through the web application,

we built two-mode networks composed of actors

represented by Cultural Heritage Objects (CHO) and

their digital representations (web resources), and

links represented by the association between CHOs

and web resources. In some cases, providers of

digital resources are museums, galleries or

individuals (called “data providers”); other times

digital resources are provided by external

aggregators who have been asked to post the

resources in lieu of the data providers who own the

resources. For instance, a CHO could be the “Mona

Lisa” of Leonardo da Vinci, and the digital resources

could be several Mona Lisa’s replica in different

formats: a Mona Lisa caricature printed on a box,

sculptures inspired by the painting, or a video

documentary on the painting itself.

We run initial experiments on the portal

Europeana.eu using basic searching options as well

as advanced ones, for example adding the string

“Who” to identify a specific author. Table 1 presents

a subset of keywords used to test the web

application: “Divina Commedia/Dante Alighieri”;

“Mona Lisa”, “all the manuscripts between the 13

th

and the 14

th

century”; “King Lear” by Shakespeare

and “La Dolce Vita” (i.e. the famous movie by

Federico Fellini). The examples shown in Table 1

have been chosen since they are representatives of

the variety of results we can obtain.

Table 1 summarizes the number of CHO shared

on Europeana by different providers. The links are

represented by the web resources associated to the

CHO, while the network density represents the

actual links between nodes out of the total possible

connections. For instance, we built the Divina

Commedia network based on 304 nodes (i.e. CHOs)

with 204 associations based on the number of web

resources associated to each CHO. The low density

for the CHO Divina Commedia indicates that there

are fewer resources shared on Europeana connecting

the cultural objects. This means that cultural objects

with a higher density are the most popular. In Table

1 most of the nodes/CHO have low density, though

King Lear seems to emerge as the one with a higher

relative popularity.

Table 1 presents also a comparison of the type of

resources available for each CHO. Users tend to

share resources that are less textual and more audio-

visual when the objects are Mona Lisa or La Dolce

Vita. This is not a surprise given the nature of those

cultural objects.

Table 1: Search Results from Europeana.

Divina

Commedia

Mona

Lisa

Manuscri

pts [1200

to 1300]

La Dolce

Vita

King Lear

Nodes

304 239 284 150 294

Links

204 139 184 51 196

Density

0.0022 0.0024 0.0023 0.00224 0.00225

Resource Type

92 text,

8 image

85

images,

31 sound,

24 text,

2 videos

22

images,

115 text

90

images, 4

sounds,3

text, 3

videos

59

images,

40 text

Visualizing Cultural Digital Resources using Social Network Analysis

191

Figure 5: Graph of the CHO Mona Lisa.

Figure 5 illustrates the network of the CHO

“Mona Lisa” and its digital resources. The colour

represents the type of resource available for the

Mona Lisa object: image, sounds, text, or video. The

size of the node is based on Betweenness Centrality,

so the bigger the circle, the most central is the

cultural object in terms of number of resources

posted on Europeana. In this case betweenness

centrality can offer some insights on the ability of a

CHO to connect different resources and different

providers, acting as hub for other nodes (e.g.

museums, experts, aggregators).

Figure 6 shows the Word Cloud View for the

cultural object “King Lear”. The colour settings

from red (negative) to green (positive) offer a first,

visual indication of the extent the words used to

describe resources are considered negative, neutral

or positive. In order to visualize the word cloud

view, we had to run a sentiment analysis on the

nodes’ description (Brönnimann, 2014, p.2). In this

case the text is represented by the description of

cultural objects and associated resources. In Figure

6, words such as “lear”, “king” or “errors” are

marked as negative, while others such as “correct”,

or “1608” are considered positive.

5 DISCUSSION

The web application we designed, applied and

described in this paper is based on a Java library

developed in an open collaborative environment.

Because of that, it is under continuous improvement.

In this early stage it offers good potential for users to

explore the wealth of cultural heritage using a single

web application, which acts as interface for any

social network analysis tool. We should not ignore

that issues of metadata interoperability still remain a

challenge, despite Europeana’s efforts to help

institutions and data providers to create a single

metadata repository. To address these issues a

“Semantic Enterprise Service Bus for Cultural

Heritage” is under development within the DiCet

project, in the aim to make accessible all the

information and contents in the field of cultural

heritage. For its design and implementation, an

ontology-based approach has been adopted, in order

to integrate different and heterogeneous data

sources.

From a technical perspective, the novelty can be

identified in the design and experimentation of a

prototype that allows a controlled extraction of data

and information from Europeana data source, in a

format that is machine readable from the SNA tool

adopted in the study (Condor). The choice to adopt

infographics map (Smiciklas, 2012) to represent the

results of data processing normally facilitate the

interpretation of data, leaving more time and energy

for action design and implementation. Finally, with

very few customizations of the code, the same set of

data can be generated for feeding other SNA tools.

This work can open new scenarios of a larger

research and development agenda that aims at

implementing and interpreting a network

representation of cultural digital resources grounded

on the use of semantic technologies.

Figure 6: Word Cloud View of CHO King Lear.

The web application described in this paper

gives the opportunity to explore other visualizations

of search results. For example, out of N objects

KDIR 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval

192

authored by a painter (e.g. Michelangelo), we might

be able to identify the most popular painting from

that same author based on the number of resources

shared by different data providers.

The research implications of this study include

the exploration of a domain with high potential for

regional development by adopting a systemic

approach which integrates network structure-based

metrics with a semantic-based approach. This paper

described preliminary results that can be replicated

using similar data extracted in other regions with

similar cultural attraction.

In terms of implications for practitioners, the

described methodology can be used to identify the

most active providers in the online social network in

order to engage them and learn from their

experience. These online contributors feed the

knowledge base with new digital contents that

represent a great attractor to enlarge the community

itself. Users can perform their research on

Europeana by using textual queries. Unfortunately,

the portal does not seem to currently allow any kind

of visual interrogation using pictorial components

(Boujemaa et al., 2002). Our web application uses

the API available for programmers so it does not use

a retrieval approach based on global visual

similarity.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The application of this prototype offers the

opportunity to identify "content gap" in an online

platform such as Europeana, helping to complete the

knowledge base with new digital resources or with

improved semantic. Our work provides also the

opportunity to policy makers and local or national

government entities to identify clusters of interest

around cultural objects, enabling the design of

marketing campaigns on the territory to promote

touristic products by targeting users with high

probability to transform the interest in actual

purchase.

Research in the area of content-based image

retrieval (CBIR) has developed several algorithms

that can realistically “return a list of images that

matches the visual perspective of their inventors”

(Kwan et al., 2011). However, there is still a

problem known as “semantic gap” for queries based

either on images or on tags, since the images or

textual results often do not correspond exactly to the

results expected by the users.

It would be an important development for the

Europeana project to include content-based image

retrieval along with text retrieval. In the future we

plan to replicate the analysis with a larger sample of

cultural heritage objects randomly selected on the

Europeana portal, designing larger and more

coordinated experiments. Further research is needed

to expand on the preliminary insights that we

obtained from these initial experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is partially supported by the project:

“PON04a2_D - DiCet LivingLab Di Cultura e

Tecnologia – INMOTO – OR.C.HE.S.T.R.A.”. The

project is funded by the Italian Ministry of

Education, University and Research (MIUR).

REFERENCES

Beaudoin J.E. (2012) A Framework for Contextual

Metadata Used in the Digital Preservation of Cultural

Objects. D-Lib Magazine. 11(11/12).

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M.G. (2006). A graph-theoretic

framework for classifying centrality measures. Social

Networks 28(4): 466-484.

Boujemaa N, Gouet V, Ferecatua M (2002) Approximate

Search vs. Precise Search by Visual Content. In

Proceedings of MIR Workshop ACM-MM.

Brönnimann, L. (2014) Multilanguage sentiment analysis

of Twitter data on the example of Swiss politicians.

M.Sc. Thesis, University of Applied Sciences

Northwestern Switzerland; retrieved from

http://www.twitterpolitiker.ch/documents/Master_The

sis_Lucas_Broennimann.pdf.

Campbell, R.S., Pennebaker, J.W. (2003). The secret life

of pronouns: Flexibility in writing style and physical

health. Psychological Science, 14: 60-65.

D’Agata R., Gozzo S., Tomaselli V. (2012) Network

analysis approach to map tourism mobility, Quality &

Quantity, 47, (6): 3167-3184.

Erétéo G., Buffa M., Gandon F., Grohan P., Leitzelman

M., Sander P. (2008). A state of the art on social

network analysis and its applications on a semantic

web. SDoW2008, workshop at ISWC.

Europeana Creative, D2.1 – Metadata Retrieval Services

Based on Semantic Web Technologies, retrieved on

05/26/2015 from http://pro.europeana.eu/files/

Europeana_Professional/Projects/Project_list/Europea

na_Creative/Deliverables/eCreative_D2.1_NTUA_v1.

0.pdf

Gawinecki, M. (2008). How schema mapping can help in

data integration?–integrating the relational databases

with ontologies. ICT School, Computer Science.

Gloor, P. Krauss, J. Nann, S, Fischbach, K. Schoder, D.

(2009) Web Science 2.0: Identifying Trends through

Semantic Social Network Analysis. IEEE Conference

Visualizing Cultural Digital Resources using Social Network Analysis

193

on Social Computing (SocialCom-09), Aug 29-31,

Vancouver.

Kwan P.W., Kameyama K., Gao J., Toraichi K. (2011)

Content-based image retrieval of cultural heritage

symbols by interaction of visual perspectives.

International Journal of Pattern Recognition and

Artificial Intelligence, 25(05), 643-673.

Miguéns, J., Baggio, R., Costa, C. (2008). Social media

and Tourism Destination: TripAdvisor Case Study.

Proceedings of the IASK Advances in Tourism

Research 2008 (ATR2008), Aveiro, Portugal, 26-28

May 2008, 194-199.

Pang B, Lee L. and Vaithyanathan S. (2002) Thumbs up?

sentiment classification using machine learning

techniques. In Proceedings of the Conference on

Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing

(EMNLP), 79–86.

Pietiläinen A.-K., Oliver E., LeBrun J., Varghese G., and

C. Diot. (2009) MobiClique: Middleware for Mobile

Social Networking. In WOSN.

Schoder, D., Gloor, P. A., & Metaxas, P. T. (2013). Social

Media and Collective Intelligence—Ongoing and

Future Research Streams. KI-Künstliche Intelligenz,

27(1), 9-15.

Shadish, W. R., Cook T.D, and Campbell D.T. (2002)

Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for

generalized causal inference." Social Service Review

76, no. 3, 510-514.

Shi, K., Gao, F., Xu, Q., & Xu, G. (2014). Integration

framework with semantic aspect of heterogeneous

system based on ontology and ESB. In Control and

Decision Conference (2014 CCDC), The 26th

Chinese (pp. 4143-4148). IEEE.

Smiciklas, M. (2012). The power of infographics: Using

pictures to communicate and connect with your

audiences. Que Publishing.

Tonti, S., Baggio, R. (2012). Organizational impacts of

social network analysis for an Italian multinational

enterprise. Turistica - Italian Journal of Tourism and

Culture, 21(1), 65-73.

Tsirliganis N., Pavlidis G., Koutsoudis A., Papadopoulou

D., Tsompanopoulos A., Stavroglou K., Loukou Z.,

Chamzas C., (2004) Archiving Cultural Objects in the

21st Century, Elsevier Journal of Cultural Heritage,

Vol. 5, Issue 4, pp. 379-384.

Xia, F., Yang, L.T., Wang, L., Vinel, A. (2012) Internet of

Things. International Journal of Communication

Systems. 25, 1101–1102.

Wasserman, S. and Faust, K. (1994). Social Network

Analysis: Methods and Applications. Structural

Analysis in the Social Sciences, Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge.

Wache, H., Voegele, T., Visser, U., Stuckenschmidt, H.,

Schuster, G., Neumann, H., & Hübner, S. (2001,

August). Ontology-based integration of information-a

survey of existing approaches. In IJCAI-01 workshop:

ontologies and information sharing (Vol. 2001, pp.

108-117).

Whitelaw, C. Garg, N. Argamon, S. (2005) Using

Appraisal Groups for Sentiment Analysis, in

Proceedings of the 14th ACM international conference

on Information and Knowledge Management, p. 631.

Zhang X, Gloor P.A., Grippa F. (2013) Measuring creative

performance of teams through dynamic semantic

social network analysis. International Journal of

Organisational Design and Engineering, 3(2): 165–

184.

Zhu, W. (2012). Semantic mediation bus: an ontology-

based runtime infrastructure for service

interoperability. In Enterprise Distributed Object

Computing Conference Workshops (EDOCW), 2012

IEEE 16th International (pp. 140-145). IEEE.

KDIR 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval

194