Exploiting the Collective Knowledge of Communities of Experts

The Case of Conference Ranking

Federico Cabitza and Angela Locoro

Dipartimento di Informatica, Sistemistica e Comunicazione,

Universit

`

a degli Studi di Milano Bicocca, Viale Sarca, 336, Milano, Italy

Keywords:

Collective Knowledge, Communities of Experts, Practice Census, Knowledge Externalization.

Abstract:

In this paper, we discuss the concept of tacit collective knowledge and focus on how to externalize it to in-

form discussion and reflective thinking within a community of expert practitioners about their own distributed

practices. We draw our approach by outlining the one we undertook in the domain of a scholarly community:

how to assess the quality of scientific conferences in the broad area of computer science and IT study. Results

show the feasibility and scalability of the approach adopted to externalize tacit collective knowledge.

1 INTRODUCTION

As rightly noted by (Hecker, 2012), in regard to the

notion of collective knowledge, little clarity and lack

of a shared understanding of the precise meaning of

the expression prevail. This ambiguity lies at the in-

tersection of two questions that usually challenge the

capability of researchers to reach clear-cut responses,

namely “what is knowledge” and “what is a collec-

tive”. Indeed, even assuming (for the sake of the ar-

gument) a clear stance on what knowledge is at indi-

vidual level, it is a challenging pursuit to bring this

notion from the individual to the group level.

When given, definitions of collective knowl-

edge are usually expressed by either enumeration of

qualifying aspects, or with as much ambiguous as

evocative and fascinating expressions. For instance,

in (Lam, 2000) these two approaches coexist: col-

lective knowledge is defined both as “accumulated

knowledge of the organization stored in its rules,

procedures, routines [, tacit conventions] and shared

norms which guide the problem-solving activities and

patterns of interaction among its members”; and also

as something that “exists between rather than within

individuals [and it is] more, or less, than the sum of

the individuals’ knowledge, depending on the mech-

anisms that translate individual into collective knowl-

edge.” (Lam, 2000).

As also noted by (Nguyen and others, 2014), this

has led to different stances on what we should con-

sider as the Collective Knowledge (CK) of (or within)

a community: “meant justified true belief or accep-

tance held or arrived at by groups as plural subjects

[. . . ]; the sum of shared contributions among commu-

nity members [. . . ]; the common state of knowledge

of a collective as a whole [. . . ]”. Many other concep-

tions have been proposed in the literature, spanning

from a strong idea of CK, intended as “what is known

by a collective, which is simply not known by any

single member of it” (e.g., how to actually fabricate

an aircraft) to a weak idea of CK, i.e., “what would

remain unknown unless some experts join together,

share their expertise, and create new understanding in

a cooperative effort to gain new knowledge”.

However, the idea that collective knowledge is

created from (or composed by) multiple individual

“knowledges” should not be given for granted or ac-

cepted uncritically. As subtly noticed by (Hecker,

2012) again, stances close to social constructionism

and discourse theory claim that “knowledge is irre-

ducibly embedded in a collective practice that under-

lies even individual knowledge and action”. There-

fore, “all knowledge is, in a fundamental way, collec-

tive” (Tsoukas and Vladimirou, 2005). Related to this

tension between individual and collective knowledge

are questions that regard, on the other hand, the tradi-

tional relationship between explicit and tacit knowl-

edge. For instance, similarly to individual knowledge,

does collective knowledge require the awareness of

the knowers to know what they know, as a group,

or just the capability to apply that knowledge profi-

ciently and effectively?

In this paper, we address how to extend the

explicit-tacit dipole (a sort of common place in the

Cabitza, F. and Locoro, A..

Exploiting the Collective Knowledge of Communities of Experts - The Case of Conference Ranking.

In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2015) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 159-167

ISBN: 978-989-758-158-8

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

159

knowledge management field), to the collective di-

mension (a much less debated issue in the field). To

this aim, we will be close to the idea of collective

knowledge of Hecker in (Hecker, 2012). He de-

notes “shared knowledge” (not necessarily at con-

scious level) the knowledge closely related to the

mesh of common experiences. These experiences

are those that people have within a common cultural

background (Collins, 2007), and withing knowledge-

sharing activities, not necessarily all of formal na-

ture (like in corporate education and training, staff

communication, and so on) but also embedded in and

constituted by social relations (Davenport and Prusak,

1998; Brown and Duguid, 1991). In particular, we

will focus on tacit collective knowledge, i.e. practice-

related knowledge that a community of practition-

ers holds and exhibits to coordinate, or just mutually

align, their activities without centralized decision-

making or explicit mutual communication. We will

also focus on how to externalize it, not necessarily in a

set of formalized “facts”, but in terms of community-

gluing narratives and discourses that are exchanged

and appropriated within that community.

This paper presents the case of conference ranking

as the output of an initiative of collective, knowledge

exploitation

1

.

With practice-related knowledge we mean some-

thing different, and wider, than either procedural

knowledge or know-how. It is what a community

of practice (broadly meant) knows, tacitly more of-

ten than not, about what its members do, that is how

single practices are articulated, even independently of

each other, to form the overall practice connoting the

community. Here ‘tacitly’ means that, a priori, no

single member can know how her community, as a

whole, performs the above mentioned set of connot-

ing practices, like performing surgical procedures in

a community of surgeons, or writing academic papers

in a community of scholars on the same topics. Exter-

nalizing tacit collective knowledge, thus, relates to a

twofold transformation: from the tacit to the explicit

dimension; and from the collective to the individual

dimension. We draw our practical approach from two

main user studies, which we undertook in large and

distributed communities of expert practitioners: one

1

The reader should mind that whether the conference

ranking itself (which we could extract from the responses

gathered during the study) can be considered the external-

ization of the tacit collective knowledge of scholars (about

which conferences are the best ones); or just an explicit el-

ement reflecting this knowledge and potentially triggering

discussion and reflection within the community itself for its

evolution, it is a matter of conceptual preferences towards

this elusive concept, and a matter of concern that is outside

the paper’s aims and scope

study has been already described both in the medi-

cal literature (Randelli et al., 2012) and in the knowl-

edge management one (Cabitza, 2012). Conversely,

the other study is presented here for the first time.

In Section 2 we will describe it in more details, in

terms of its main motivations, the methods we em-

ployed to externalize collective knowledge, and the

results obtained. The following discussion will make

points to propose some general ideas on tacit collec-

tive knowledge externalization, also as triggers for

further discussion and awareness-raising in commu-

nities of practice.

2 THE CASE OF THE HCI

RESEARCH COMMUNITY

The case at hand regards a user study that we under-

took in April 2015. This study was promoted at a

joined national meeting of two organizations of com-

puter science and IT scholars and professors in Italy,

namely the GII (Group of Italian Professors of Com-

puter Engineering) and the GRIN (Group of Italian

Professors of Computer Science), collecting around

800 members each. These joined their forces to pro-

pose to the National Agency for Research Assessment

a reference classification, or unified ranking, of com-

puter science international conferences (on the basis

of their impact and alleged quality). The goal was to

propose that works published in the proceedings of

conferences could be considered in the next national

research assessment exercise, as the previous one had

been focused on journal publications solely. The GII-

GRIN joint task force thus produced “the GII-GRIN

Computer Science and Computer Engineering Con-

ference Rating” (in what follows simply the “GII-

GRIN conference rating”): this rating

2

was produced

by implementing an algorithm capable of processing

three of the main conference rankings available on-

line

3

. After a round of iterations, this algorithm was

capable of indexing 3,210 conferences and success-

fully rank 608 out of these (19%), by associating them

to one out of three quality classes

4

. In all those cases

(the large majority) where the algorithm could not

take a decision on the basis of the available infor-

mation, the GII-GRIN conference rating system re-

ports the conference as associated with a provisional

2

Available at http://goo.gl/Ciiyb8.

3

Namely, the Computing Research and Education Asso-

ciation of Australasia, or CORE; the Microsoft Academic

Search Conference Ranking, or MAS; and the Brazilian

Simple H-Index Estimation, or SHINE

4

1 – excellent conferences, 2 – very good ones, 3 – good

quality ones

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

160

“work-in-progress” (W) class.

Shortly after the publication of this conference

classification many contrarian voices raised among

the members of both the GII and the GRIN groups,

especially from members of the smaller research com-

munities within these larger groups. In fact, there

was a general consensus on the need for consider-

ing also conference papers, not only journal articles,

in research assessment. This was mainly because, as

it was often maintained in public debates and on the

group mailing lists, computer science conference pa-

pers (differently, e.g., from medical papers) are often

major works that require great efforts and resources,

and that are not necessarily extended into a journal

version. There was also consensus on the sensibleness

to assess the quality of those works as inherited from

the conference quality, in analogy with how journal

papers are evaluated without resorting to costly peer-

reviews.

However, there was little agreement on how this

conference quality could be assessed and established.

The GII-GRIN joint committee assumed an algorith-

mic and bibliometric approach to be both feasible and

sensible to this aim, and actually produced the world

most complete conference rating publicly available in

2015. However, a lively debate was triggered within

both the GII and GRIN groups on the opportunity to

ground any research assessment effort on this rating.

Some scholars were very wary of approaches rely-

ing on either obsolete or questionable rankings (like

the CORE one). Others contested the legitimacy of

a quantitative approach to gauge conference quality,

and rejected the idea that to that aim rankings based

on strictly quantitative bibliometric indicators like the

h-index should be used (as in the MAS and SHINE

cases). In particular, those contesting the legitimacy

of rankings based on the h-index usually mentioned

the distortions that bibliometrics can entail. Notably,

that conferences that either had already collected pa-

pers for decades, that usually receive thousands of

submissions at every edition, or that exhibit higher

than average acceptance rates (or all these conditions

together) would necessarily rank much higher than

more recent conferences. These are conferences as-

sociated with smaller communities of scholars, and

those that usually accept only a small number of pa-

pers. Anecdotal evidence was often reported to back

up this claim.

The above-mentioned discussion was then about

the elusive concept of quality of a scientific confer-

ence, and there were many comments referring to

well known scientometrics articles, e.g., (Arnold and

Fowler, 2011; Castellani et al., 2014; Voosen, 2015;

Weingart, 2005). These works are questioning rank-

ing based on indicators like the h-index, or the op-

portunity to conceive any ranking “per se”. In this

lively debate, our research team proposed an alter-

native, or better yet, a complementary way to assess

the quality of the conferences. Instead of calculating

the h-index or composing different rankings together,

we made the point to base this idea on the perception

of experts. These experts are the ones who: would

disseminate the calls for papers of those conferences;

spend money to attend them; either write or review

papers to be published in their proceedings; and study

their works on a daily basis for both education- and

research-oriented purposes. In short: to ask the ex-

perts, and tap in the tacit collective knowledge about

the practices of preparing works for and then attend-

ing scientific conferences, in order to understand if

their quality could be thus assessed.

To this idea, various objections were raised at the

GII-GRIN meeting, especially in regard to two main

aspects. First, on how to assess this collective per-

ception or sort of know-what, i.e., knowing whether a

conference is of high quality or not. Second, on the re-

liability of opinions that could be biased by a conflict

of interest in that (it was alleged) scholars would at-

tribute a higher quality to the conferences whose pro-

gram committees they are members of, or to those for

which they had published more often, and so forth.

It was odd then to see voices raising from the sci-

entific community (where a keen attention is being

paid to phenomena like the “wisdom of the crowd”)

expressing a much higher wariness towards a method

of collective participation than a more allegedly con-

servative community like the medical one. To chal-

lenge these voices, we proposed to test the feasibil-

ity of the same method we had applied in the med-

ical domain to the academic community. We hy-

pothesized that, on average, the respondents would

express unbiased opinions on the conference quality

grounded on their frequent attendance, tacit recogni-

tion and practice-related knowledge.

3 THE PILOT SURVEY

In order to test the feasibility and soundness of our

proposal, it was decided that the informal community

of scholars interested in the Human-Computer Inter-

action (HCI) field would be involved in a pilot ex-

perience. On the basis of this experience then, the

GII & GRIN groups would deliberate whether to ex-

tend this method to the whole community, and there-

fore to the whole set of indexed conferences.

In this section, we describe this pilot survey. This

survey took three weeks in April 2015, in which we

Exploiting the Collective Knowledge of Communities of Experts - The Case of Conference Ranking

161

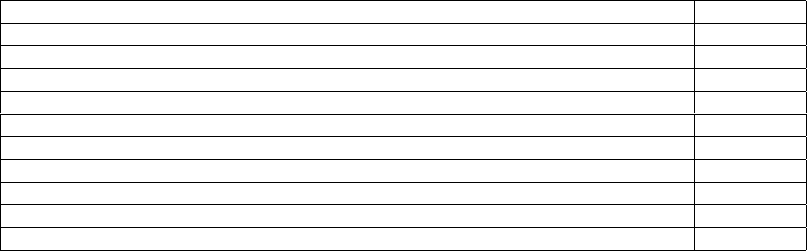

Table 1: The list of the ten conferences more frequently evaluated.

Conference name No. of Eval.

CHI - ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing System 67

AVI - Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces 34

CHITaly - biannual Conference of the Italian SIGCHI Chapter 34

INTERACT - IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction 32

NORDICHI - Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction 23

CSCW - ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing 21

VL/HCC - Visual Languages and Human-Centric Computing 17

IUI - ACM International Conference on Intelligent User Interface 17

MobileHCI - Int.Conf.on Human Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services 15

ECSCW - European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work 14

sent an invitation and two reminders to all of the Ital-

ian HCI experts (to our knowledge). They were in-

vited to participate in an attitude survey and fill in

a brief closed-ended questionnaire by which to col-

lect their opinions about the quality and selectivity

of international conferences. These conferences were

those with which they felt to have high familiarity,

either for their direct experience (e.g., regular atten-

dance) or for their knowledge of the conference topics

(and papers).

HCI experts were selected among the subscribers

of the HCITaly mailing list and of the mailing list of

the Italian Chapter of the SIG-CHI group, as well as

by considering all the program committee members of

the two main HCI Italian conferences (i.e., CHItaly

and the ItAIS HCI track). The reference population

encompassed approximately 340 names and email ad-

dresses, whereas a precise number is impossible to

retain for the data quality problems that resulted to

affect the two former mailing lists (some addresses

were plainly wrong, others were clearly obsolete, for

others the contacted mail servers returned various er-

rors, and there were also a number of homonyms and

duplicates).

When we closed the survey, we had collected 83

complete questionnaires, but we were able to use also

the responses from other questionnaire filled in only

partially, so that we can claim to have collected the

opinions from 135 domain experts. Therefore, by a

cautious estimate (considering the data quality issues

mentioned above), we can state to have involved more

than a third of the Italian scholars actively involved in

the HCI field (i.e., roughly speaking around the 38%

of the reference population), whose profile is outlined

in the next section.

3.1 The Respondent Profile

Some items from the first part of the questionnaire

were aimed at collecting profile-related information

from the involved respondents. This allows us to par-

tition the sample of respondents as follows:

• the 70% had worked at a university in the last 5

years;

• the 16% had worked mainly at a research institu-

tion;

• the 12% had worked mainly in the private sectors;

• the 2% claimed to have had other professional ex-

periences.

In regard to expertise (a critical aspect of our sur-

vey), two thirds of the respondents (67%) claimed to

have a 10-years experience in the HCI field, and the

86% claimed to have an experience of at least 6 years:

in other words, around 9 out of 10 respondents may

be considered experts, according to the most accepted

and reasonable definition of the term e.g., (Herling,

2000; Gladwell, 2008).

In regard to their (self-proclaimed) areas of ex-

pertise, the respondents could choose labels from the

ACM 2012 classification under the main “Human

Centered Computing” category. On average, the re-

spondents felt to be better represented by 2.3 labels

(SD=0.7), and only the 22% identified their main re-

search area in terms of the most generic class (“Hu-

man Centered Computing”), whereas 72% of the re-

spondents chose the more traditional label of “Hu-

man Computer Interaction”. Among the sub-area la-

bels, the ones mentioned more frequently were: “In-

teraction Design” (chosen by half of the respondent

sample - 51%); “Ubiquitous and mobile computing”

(chosen by a third of the respondents - 32%); and two

other areas chosen by almost a quarter of the respon-

dents: “Collaborative and Social Computing” (which

also included “Community Informatics” and “Knowl-

edge Management”); Visualization (including “Visual

Languages” and “Visual Interfaces”), chosen by the

24% and the 22% of the sample, respectively. The

least represented area resulted to be “Accessibility”

(which included also HCI4D), which was chosen by

only one respondent out of ten (ca. 10%).

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

162

The online questionnaire also allowed the respon-

dents to indicate a further free-text label closer to their

interests or better representing their research area.

Only one respondent out of ten opted for this opportu-

nity, which can be taken as a sign that the Italian HCI

community perceives the ACM classification suffi-

ciently fit for representing their expertise. The ad-

ditional research areas were: Recommender systems

(3%); Intelligent Interfaces (2%); and then CSCL, AI,

HF, VR, UX e Art&Digital Media, which collected

just one vote each.

From these figures, it is reasonable to conclude

that the Italian HCI community is quite various

and, as it was argued during the GII-GRIN meeting,

likely one of the most heterogeneous areas within the

GII & GRIN groups.

3.2 The Evaluation of Conferences

After the profiling questions, the respondents were

asked to choose at most 20 conferences about which

they felt confident enough to express a judgment

about their quality (for whatever reason and either in

the positive or the negative side). The respondents

could select the conferences from a list that had been

previously selected by our research team, encompass-

ing 171 conference abbreviations, acronyms and full

names. They could also insert a conference name

manually, in case this was not listed. Table 1 shows

the ten conferences that received more evaluations in

descending order. This list is an informal indicator of

the more popular conferences within the Italian HCI

community.

We collected a total of 689 evaluations, for a total

number of 124 conferences, out of which exactly one

third was manually added by the respondents.

In order to proceed with the statistical analysis,

we first had to find a way to minimize dispersion,

which can have a deep impact on the statistical analy-

sis of the responses. To this aim, we focused on those

conferences that had collected a least 3 evaluations.

These latter ones were less than the half of the con-

ference sample: 50. This result can be interpreted

in a twofold way: as a positive achievement, in that

we succeeded in collecting useful information for 50

conferences in a specific area as HCI. On the nega-

tive side, 3 evaluations could be considered too few to

get sound results in specific statistical tests, and a low

number of evaluations may likely cause an overesti-

mation of the conference at hand. That notwithstand-

ing, if we had kept only those conferences that had

got at least 5 evaluations (a common rule-of-thumb

threshold for most statistical tests) we would have

discarded more than the half of the total conferences

evaluated in this user study. Extending this experi-

ence to the GII-GRIN population would then allow to

reach a 5-fold wider population than the HCI com-

munity, but this would not alone guarantee a much

higher number of evaluated conferences, due to the

great heterogeneity in interests and competence areas

of the whole population.

For this reason, it could be reasonable to circum-

scribe the extension of the method presented in this

paper only to those conferences that the bibliomet-

ric approach (mentioned in Section 2) was not able

to classify (i.e., 2,814 conferences in total). Or, con-

versely, to ask for the experts’ opinion only in regard

to those conferences for which the GII-GRIN confer-

ence rating provide a relevant class (i.e., 396), so that

it could act as a countercheck study (we will come

back to this topic in Section 4).

Although the system allowed to evaluate up to

20 conferences, only three respondents evaluated the

maximum number allowed. On average, each respon-

dent evaluated 5.1 conferences. On one hand, this rel-

atively low number could support the idea that respon-

dents only evaluated those conferences that they felt

more confident about. On the other hand, we could

conjecture that they focused on those that they wanted

to appraise positively. Both these drivers could obvi-

ously be factored in to account for this level of partici-

pation. As a matter of fact, two respondents contacted

one of the authors during the survey confessing to feel

awkward in giving bad grades, and to have restrained

themselves in expressing their negative opinion in re-

gard to a number of conferences. Thus, both the low

number of conferences evaluated and this latter fac-

tor could give a context for the interpretation of the

results.

Furthermore, each respondent was (on average),

author of 2 out of the 5 conferences she evaluated

(SD=2.5), and was, on average, member of the Pro-

gram Committee of 1.8 (SD=3) conferences. Au-

thorship and PC membership were then treated as

dichotomous variables to assess the alleged “self-

boosting” effect. To this regard, we found a mod-

erate correlation both between the number of evalu-

ated conferences for which one has published a pa-

per and the average quality of the evaluated confer-

ences (Pearson Rho: .27, p=.000) and between this

cumulative score and the number of conference for

which one has been a PC member (Rho: .24, p=.000);

also a Mann Whitney test confirmed that differences

between who is not an author of the conference that

she has evaluated and who was an author, as well as

between who was not a PC member and who was a

PC member, are statistically significant (U=604.5 and

U=1005, and mean ranks 49.6 vs. 82, 39 vs. 84.3

Exploiting the Collective Knowledge of Communities of Experts - The Case of Conference Ranking

163

respectively, p=.000). However, this does not neces-

sarily prove a “self-boosting” effect, but rather that

having been either an author or a PC member corre-

lates positively with higher evaluations: more fine-

grained analysis, at the level of the single conference

could address this effect, which nevertheless can not

be ruled out.

3.3 The Classification Results

The questionnaire allowed to collect data along three

different dimensions, addressing the concept of per-

ceived quality from three complementary perspec-

tives:

1. A range of classes associated with different, dis-

crete quality levels: Excellent quality (A), Good

quality (B), Sufficient quality (C) and Negligible

quality (D).

2. The average quality of the works presented at the

conference, to be expressed on a 6-value semantic

differential rating scale from “very high quality”

to “very low quality”.

3. The selectivity of the conference, to be expressed

on a 6-value semantic differential rating scale

from “very selective” to “not at all selective”.

In regard to the first dimension, we were aware

of a number of criteria by which a class could be

assigned to each conference. In order of increasing

conservativeness, eligible criteria are: i) relative ma-

jority; ii) absolute majority; iii) reaching a predefined

proportion threshold (e.g., 75%) or a sufficient agree-

ment score (e.g., 70%).

Majority-based criteria can be applied either with

or without statistical significance with respect to the

difference between the number of collected responses

for the class ranked first and the second class. To take

an example from the detailed results we obtained, the

85% of the raters of the CSCW conference assigned

it the A class, therefore this conference can be clas-

sified in that way with a high confidence. On the

other hand, 53% of the raters of the CHITaly con-

ference assigned it the B class, but this assignment

(which is sound according to both the criteria of rel-

ative and absolute majority) did not differ with suf-

ficient statistical significance from the assignment to

the C class, with respect to the number of “votes” for

either classes (Chi-square=.81, p-value=0.37). Also

in the case of the itAIS conference, the class chosen

by the absolute majority of the raters (i.e., C, by the

62%) cannot be assigned with statistical significance,

for the low number of raters involved (8 raters, p-

value=.48). In light of these considerations, in this

pilot study we preferred to adopt the first criterion

mentioned above quite naively and leave to the com-

munity debate the choice of the most suitable classi-

fication algorithm that could leverage the opinions of

the experts involved.

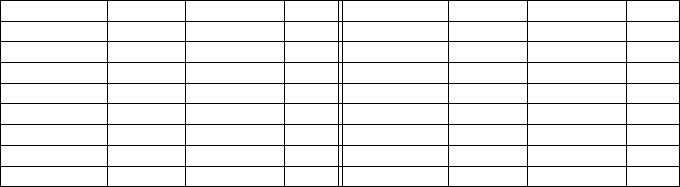

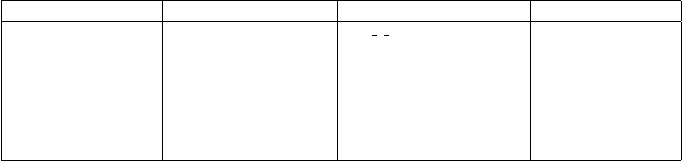

In Table 2, we report the “conference – class” as-

sociation as it resulted from the analysis of the col-

lected responses (only for classes A and B), and we

compare the class suggested by the Italian HCI ex-

perts with the related class assigned by the bibliomet-

ric GII-GRIN algorithm. As hinted above, this latter

conference rating either assigns a classifying category

(1, 2, or 3) or a W category, that is a sort of a “Don’t

know’ class (mainly due to lacking of sufficient data

for the algorithm to make a decision). We indicate

with a ‘not indexed’ indication (n.i.) all those confer-

ences that were considered in the HCI user study but

were not found in the GII-GRIN conference rating.

3.4 Comparing the GII-GRIN and the

Collective Knowledge Approaches

By comparing the classification derived from the ex-

perts’ collective judgment and the classification pro-

duced by the bibliometric algorithm of the GII-GRIN

conference rating introduced in Section 2, we can

make some points, especially as triggers for discus-

sion within the community of computer science schol-

ars, not necessarily limiting to the Italian case:

• Selecting all the conferences that can represent

completely the interests of a wide research com-

munity can be a discouraging effort. In prepar-

ing the list of HCI conferences from which the

survey participants could choose theirs, we be-

lieved to have selected any possible option. Yet,

we were wrong: one third of the evaluated con-

ferences were added by the respondents. Simi-

larly, a massive algorithmic effort indexing more

than 3,000 conferences, like the GII-GRIN con-

ference rating, failed to cover the HCI area en-

tirely: 5 out of the 44 conferences evaluated by

our panel (11%) were not indexed (denoted as n.i.

in Table 2).

• Expert-based methods can complement biblio-

metric classification. This is justified by the fact

that one third of the conference set evaluated in

our user study (15 conferences) were not classi-

fied in the GII-GRIN conference rating due to lack

of data (see the W classes in Table 2 )

• The expert classification and the GII-GRIN con-

ference rating, when they both classify a confer-

ence, differ in a significant manner. This is prob-

ably a striking finding of the present study. Both

classifications overlapped with respect to 24 con-

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

164

Table 2: The list of conferences with: votes for the class A; the GII-GRI rating; the difference between these two classifications

(more circles, greater difference; ’=’ is coincidence).

Conference Experts GII-GRIN diff. Conference Experts GII-GRIN diff.

CHI A 1 = DIS A 2 •

RecSys A 3 •• InfoVIS A 1 =

UIST A 1 = PDC A 3 ••

CSCW A 1 = IUI A 2 •

WWW A 1 = VAST A W -

ECSCW A 2 • TEI A 3 ••

UMAP A 3 •• UbiComp A 1 =

AVI A 3 •• ASSETS A 3 ••

ferences: in more than the 60% of the cases their

rating differed from each other: in 9 cases (out

of 24) the experts confirmed the bibliometric rat-

ing; in 15 cases they (tacitly) contested it, giving

always a higher rating.

3.5 The Psychometric Results

As said above, we also asked the respondents to eval-

uate their conferences along two clearly related di-

mensions: the paper quality and the selectivity (as

these could be subjectively perceived by our respon-

dents). The internal reliability of these two constructs

(calculated for the conferences with more than 20

evaluations) was found to be generally acceptable,

even good for some conferences (Cronbach’s Alpha

M=0.68, SD=0.16, max 0.88). Correlation between

these two items for the most popular conferences

was found to be moderate to strong (Spearman Rho

M=0.56, SD=0.15).

The use of ordinal scales allows for two kinds

of analysis: the detection of any response polariza-

tion and indirect conference ranking. In regard to

the former analysis, we performed a binomial test on

the (null) hypothesis that positive and negative per-

ceptions of paper quality were equally likely to oc-

cur. This test allows to detect any polarization in

the response distribution stronger than those due to

chance alone, and to see if the respondent sample ex-

presses an either positive or negative attitude towards

the items (i.e., in this case conference quality and se-

lectivity). As a result, we found that the paper quality

was deemed to be positive for all of the conferences

(in 18 cases also with statistical significance), with

only one exception that nevertheless was not statisti-

cally significant (ItAIS, 6 negative votes vs. 2 posi-

tive votes, p=0.29). In regard to the selectivity dimen-

sion instead, only in 2 cases the community expressed

a low selectivity, and in no case with a clear statis-

tical significance. The latter kind of analysis, con-

ference ranking, requires a more complex procedure.

One possibility would be to compose both the dimen-

sions into a compound index (for example through

the “Categorical Principal Components Analysis” or

CATPCA technique); in so doing, a joint quantitative

ranking would be created on the basis of the index

average among the various respondents. This pos-

sibility notwithstanding, we proceeded in a different

way in order to minimize the “self-boosting effect”

mentioned above: to this aim, we applied an original

method that we had already validated in other stud-

ies (Randelli et al., 2012) that creates what we call

an indirect conference raking. This is a ranking of

items (in this case conferences) that is produced on

the basis of the ordinal ratings of the single experts in-

volved. However, it does not accomplish this task by

simply extracting a central tendency parameter of the

distribution of the ratings (like in most cases means

or medians). Rather, we derive the global ranking in-

directly by aggregating the single rankings implicitly

expressed by the individual raters in terms of relative

votes. This would address any manifest and mali-

cious abuse of the rating procedure as it creates partial

rankings for each rater with the standard competition

strategy (also called 1224 to hint at how joint winners

are dealt with). In the worst case, where a respon-

dent gives “her” conferences the highest ordinal cate-

gory (namely 6), she is just telling our algorithm that

those conferences are all evenly matched for her and

her preferred conferences, without inflating the qual-

ity value of those conferences. In so doing, we created

a “conference – paper quality level” association, that

we report in Table 3. The same procedure can also

be applied to the selectivity construct, which we saw

above being moderately correlated to the paper qual-

ity one, and for this reason we do not report for the

sake of brevity. The ordinal values collected for both

these constructs (or any other that other researchers

would find pertinent in characterizing the conference

quality macro-construct) can be aggregated in a joint

score and then this latter one be used by our ranking

method. Or conversely, two independent rankings can

be produced, and then aggregated in their turn into a

single one ranking by adopting simple scoring con-

ventions.

Exploiting the Collective Knowledge of Communities of Experts - The Case of Conference Ranking

165

Table 3: The ranking of conferences according to paper quality.

high quality probable high quality probable lower quality lower quality

CHI, RecSys, UIST,

CSCW, ECSCW,

WWW, UMAP,

MobileHCI,

AVI, DIS,

InfoVIS, EuroVis,

PDC, IUI, VAST,

EICS, UbiComp,

INTERACT,

IS-EUD, NORDICHI,

TEI, PERCOM,

BHCI, ASSETS

CT - IADIS, ACII,

PERSUASIVE,

KMIS, CoopIS,

C&T, GROUP, ICMI,

IDC, AmI, CHITaly,

ICWE, INTETAIN, CTS

VL/HCC, DMS,

SEKE, DET, itAIS

4 DISCUSSION

In this paper, we have made the point that communi-

ties of expert practitioners can be involved in initia-

tives of knowledge externalization. This latter con-

cept is conceived as the collection and statistical anal-

ysis of the practice-related preferences, opinions, per-

ceptions and attitudes of each potential single prac-

titioner. This concept was argued in two distinct

scientific domains, where the attitude towards this

kind of approach is highly different. In one domain,

the medical one, of which we reported in the previ-

ous studies referenced in Section1, the opinions of

experts is valued as essential in the construction of

any consensus-based and community-representative

guideline or quality criteria. In the other domain, the

academic one in the computer-related fields, there is a

much stronger caution that collective knowledge can

be properly extracted and above all, that this would

really reflect actual behavioral patterns and practice-

informed convictions, rather than either partisan or

personal interests.

To investigate the feasibility of the approach that

other domains appraise for the continuous develop-

ment and reflection on situated professional practice,

we deliberately chose a topic that has raised the most

lively debates within our scholarly communities in

recent times: how to assess the quality of scien-

tific conferences, and whether this could be assessed

on merely quantitative, bibliometric (h-index-based)

methods.

While the education and research associations

that had promoted the study have not yet deliberated

whether to scale the initiative to the whole community

of their members, or to consider it just an interesting

experience in the hard times of research assessment

efforts, we can draw some points from the fast trajec-

tory of the project.

According to the experts’ perceptions very few

conferences could be considered of low quality, per-

haps not surprisingly. Moreover, the few cases of col-

lective negative rating could not be associated with

sufficient statistical significance (due to the relative

low numbers of evaluations). This means that differ-

ent samples of respondents could either tip the bal-

ance in favor of those conferences, or conversely con-

firm the low rating with a stronger confidence.

These cases notwithstanding, this study succeeded

in collecting the opinions and perceptions of more

than a hundred of experts in relatively short time and

with very limited resources. A number that, to any

practical aim, should not be underestimated. In so do-

ing, we collected a sufficiently high and sufficiently

heterogeneous number of evaluations, so that it was

possible to identify three quality macro-levels, and

put in those classes approximately 50 conferences:

• high quality with statistical significance;

• lower quality with statistical significance (NB

lower, but not necessarily low, as said above);

• uncertain conditions mainly due to sample bias.

The case of conference quality (but a similar argu-

ment could be made for journal quality and so forth)

is paradigmatic, especially in light of the well known

disagreement regarding quality assessment on the ba-

sis of bibliometric indicators only.

The tool used in this study, i.e., a short multi-page

online questionnaire with tokenized access, and the

method to extract sound findings from the collected

response set, have been designed so that they can eas-

ily “scale up”, either in regard to the number of re-

search “objects” to evaluate (conferences, journals,

and the like) and in the number of potential respon-

dents.

The results show that multiple expert scholars can

be involved to either classify conferences according

to their perceived quality and reputation within their

scientific community, or to build a ranking that is al-

ternative to those produced on a bibliometric basis. To

this latter aim, the impact of personal interests should

be further investigated, although this study tried to ob-

jectify and also minimize it by adopting an original

method of indirect ranking.

As the number of relevant conferences, or which

are just pertinent to a research area, is very high (more

than 200 in a specific area like HCI, and more than

3,000 in the main computer science sub-fields), ap-

proaches tapping in the experts’ perceptions could

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

166

suffer from evaluative dispersion, that is relatively

few conferences could get enough ratings to allow for

sound classification and fair, unbiased ranking tasks.

That notwithstanding, also the GII-GRIN conference

rating was capable to classify less than one conference

out of five whose data are retrievable online.

This suggests that bibliometric and expert-driven

methods can at least complement and enrich each

other in regard to two aspects. On the one hand, ex-

perts could be involved at first in addressing the high

number of unclassified conferences (denoted with W

by the GII-GRIN conference rating). This W may be

due to either intrinsic limits of the classification algo-

rithm, lack of available data or a combination of these

factors. On the other hand, experts could also be in-

vited to explicitly express their degree of agreement

with each item from a systematic list of conference

ratings (produced on the basis of the h-index or sim-

ilar indicators) according to their experience and per-

ception. Only if this agreement were low, they could

be asked to provide their alternative indications. In

so doing, even long lists of conferences could be re-

viewed in a relatively short time, and the quantitative

rating could be complemented with local proposals of

correction, whenever a certain number of respondents

express their discord.

This paper therefore can be seen as a contribu-

tion to the specific aim of engaging experts in im-

proving the assessment of the quality of research-

related entities (like conferences, and journals). To

this perhaps limited aim, yet, this study also extends

known best practices, which are already adopted in

the peer-review of scientific papers, and improves

them with statistical techniques specifically applied or

conceived to leverage the collective opinion (that is,

knowledge) of a large set of domain experts. To this

more general respect then, this work can also be seen

as a practical contribution to research agenda that are

aimed at tapping in the collective knowledge, intel-

ligence and wisdom of large communities of experts

for their progressive, continuous and reflective devel-

opment, especially in regard to matters that are central

to their development and evolution.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the collaboration of

Carmelo Ardito and Massimo Zancanaro who con-

tributed for the HCI conference list, and Francesca

Costabile, Carlo Batini and Paola Bonizzoni who

greatly supported the initiative within the GII and

GRIN associations.

REFERENCES

Arnold, D. N. and Fowler, K. K. (2011). Nefarious numbers.

Notices of the AMS, 58(3):434–437.

Brown, J. S. and Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning

and communities-of-practice. Organ. Sci., 2(1):40–

57.

Cabitza, F. (2012). Harvesting Collective Agreement in

Community Oriented Surveys: The Medical Case. In

From Research to Practice in the Design of Coopera-

tive Systems, pages 81–96. Springer.

Castellani, T., Pontecorvo, E., and Valente, A. (2014).

Epistemological Consequences of Bibliometrics. Soc.

Epistemol., 3:1–20.

Collins, H. (2007). Bicycling on the moon: collective tacit

knowledge and somatic-limit tacit knowledge. Organ.

Stud., 28(2):257–262.

Concato, J., Shah, N., and Horwitz, R. I. (2000). Ran-

domized, Controlled Trials, Observational Studies,

and the Hierarchy of Research Designs. NEJM,

342(25):1887–1892.

Davenport, T. H. and Prusak, L. (1998). Working knowl-

edge: How organizations manage what they know.

Harvard Business Press.

Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The Story of Suc-

cess.Hachette, UK

Hecker, A. (2012). Knowledge beyond the individual?

Making sense of a notion of collective knowledge in

organization theory. Organ. Stud., 33(3):423–445.

Herling, R. W. (2000). Operational Definitions of Exper-

tise and Competence. Adv. Develop. Hum. Resour.,

2(1):8–21.

Lam, A. (2000). Tacit knowledge, organizational learning

and societal institutions. Organ. Stud., 21(3):487–513.

Nguyen, N. T. and others (2014). Processing Collective

Knowledge from Autonomous Individuals: A Litera-

ture Review. In Advanced Computational Methods for

Knowledge Engineering, pages 187–200. Springer.

Randelli, P., Arrigoni, P., Cabitza, F., Ragone, V., & Cab-

itza, P. (2012). Current practice in shoulder pathology.

Knee Surg Sport Tr A, 20(5), 803-815.

Tsoukas, H. and Vladimirou, E. (2005). What is organiza-

tional knowledge? Managing Knowledge: An Essen-

tial Reader, page 85.

Voosen, P. (2015). Amid a Sea of False Findings, the NIH

Tries Reform. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Walker, A. and Selfe, J. (1996). The delphi method: a useful

tool for the allied health researcher. Int J Ther Rehabil,

3(12):677–681.

Weingart, P. (2005). Impact of bibliometrics upon the sci-

ence system: Inadvertent consequences? Scientomet-

rics, 62(1):117–131.

Exploiting the Collective Knowledge of Communities of Experts - The Case of Conference Ranking

167