Support Technology in Sport Psychology

Career Transition of Elite Athletes: Role of Mental Training

Ikuko Sasaba

1

and Haruo Sakuma

2

1

Graduate School of Sport and Health Science, Ritsumeikan University,

1-1-1 Noji-higashi, Kusatsu, Shiga, 525-8577, Japan

2

Department of Sport and Health Science, Ritsumeikan University, 1-1-1 Noji-higashi, Kusatsu, Shiga, 525-8577, Japan

Keywords: Elite Athletes, Mental Training, Career Transition, Case Study Approach, Biofeedback.

Abstract: Presently, various technologies are used more and more often in the field of sport psychology. This paper

introduces two cases of how elite athletes use support technology in their mental training. One of the cases

involves the use of Information Communication Technology (ICT), described in detail as qualitative research

regarding elite athletes facing career transition. Becoming an Olympian dominates athletes’ entire lives. Elite

athletes’ need for career transition support has recently become more recognized; therefore, international

sports powerhouses tend to provide their own national support programs for elite athletes during their career

transitions; for instance, the Japanese Olympic Committee began a career support program in 2004. In parallel

with similar movements around the world, sport psychology consultants are often naturally called upon to

address career transitions when working with elite athletes. The results show athletes’ needs for career

transition support and how sport psychology consultants can help these athletes as ultimate stage of their

mental training. Possible interventions (approaches) are also presented.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, sport psychology has become more

recognized worldwide as one of the key aspects for

performance enhancement among elite athletes

(Gould and Maynard, 2009). In parallel with

international tendency, the Japanese government

started national support projects, including those in

the sport psychology field for Olympians before the

London Olympics (Japan Institute of Sport Sciences,

2012).

1.1 Introducing Case 1: Biofeedback in

Sport Psychology

Mental training is one of the most well-known

representative approaches in the field of sport

psychology. A huge variety of approaches are used

for mental training. In addition to one-on-one

sessions (counseling), scientific approaches using

technology such as biofeedback have become more

recognized (Galloway, 2011); (Paul and Garg, 2012).

Biofeedback helps athletes develop self-regulation

skills for relaxation and concentration (Muench,

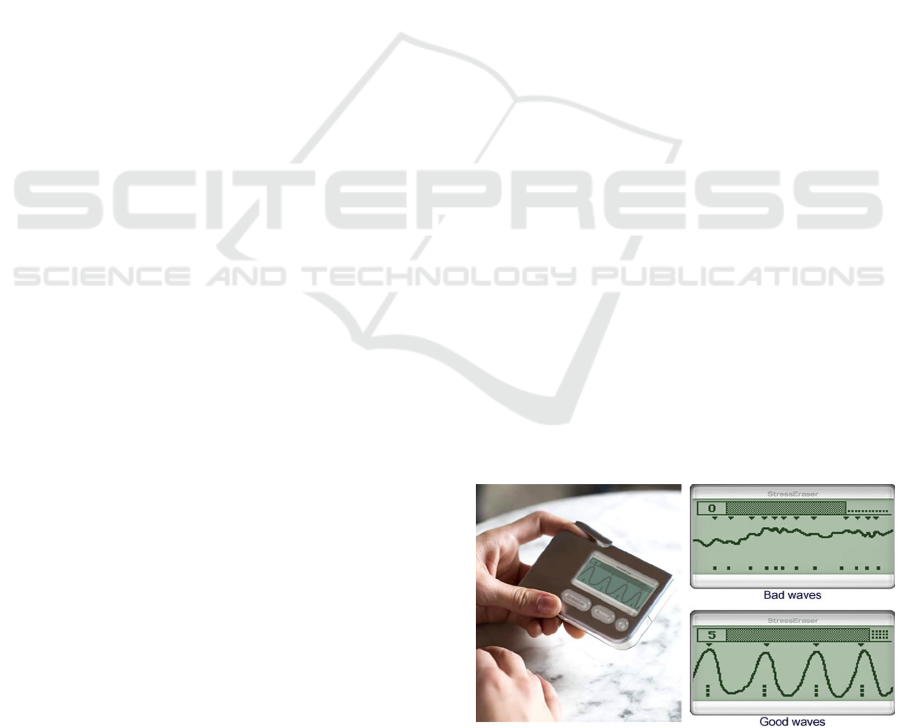

2008); (Hayden, 2008). StressEraser, a small real-

time biofeedback device manufactured by Helicor

Inc., played an active role in helping athletes acquire

breathing techniques as one of their relaxation skills

in preparation for the 2012 Olympics (Sasaba and

Sakuma, 2014). The device helps visualize the

transition of parasympathetic nerves’ predominant

points during relaxation training. Therefore, athletes

could modify their breathing approaches, such as the

rhythm or length, to acquire precise breathing for

relaxation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Stress Eraser and the examples of bad waves and

good waves.

http://item.rakuten.co.jp/baleno/10010160/

126

Sasaba, I. and Sakuma, H..

Support Technology in Sport Psychology - Career Transition of Elite Athletes: Role of Mental Training.

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Congress on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support (icSPORTS 2015), pages 126-131

ISBN: 978-989-758-159-5

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

One big question exists in Mental Training. After

elite athletes complete the relaxation training in a

laboratory environment, “How do the mental skills

actually affect performance in actual sports?” “Can

they use the skills correctly even under high pressure

just as they did in a laboratory?” Kinect (Microsoft

Co., Ltd.), a noncontact motion-capture device, can

help in these situations (Sasaba and Sakuma, 2015).

Kinect measures heart rate, breathing rate, and

respiratory curve. When athletes need relaxation for

their sports, they can confirm their concentration state

and relaxation state in actual sports situations,

especially right before performing, just by sitting in

front of the Kinect (Figures 2-4).

Figure 2: Kinect (Microsoft Co., Ltd.).

Figure 3: Right before his performance, using breathing

techniques to concentrate.

Figure 4: Right after the concentration, he performs as in

competition (simulated actual competition situations).

1.2 Case 2: The Use of ICT in Sport

Psychology

There are two examples in recent Olympics, where

mental training was typically perceived and utilized

as preparation for athletes. Blumenstein and Lidors’

(2007, 2008) studies introduced unique and long-term

programs provided to Israeli elite athletes before the

Beijing Olympics. They customized their program

each year based on characteristics of the sport,

experience of the athletes, and individual needs from

the athletes. Another example, also described as a

long-term psychological intervention, and crucial for

success as a mental preparation, was developed for

the US team at the Olympics. They explained that

athletes’ needs changed in stages. Even right before

their events during their stay in the Olympic Village,

athletes required psychological support (McCann,

2008).

As shown in these examples, elite athletes require

long-term support, not a one-shot approach, and

consultants are often required to provide professional

guidance from long distances because elite athletes

travel worldwide for competitions and long-stay

training camps abroad. Moreover, specifically World

Championships or Olympics, consultants have

limitations when it comes to meeting in person with

athletes for many reasons. To meet the needs of elite

athletes, ICT is the key. Zizzi and Perna (2002)

described that Internet-based interventions have

increased within the last decade. Although athletes

can easily find many sport psychology consultants’

websites offering Internet-based interventions,

surprisingly, very little research about this exists.

These days, many ICT tools such as e-mail,

Skype, or FaceTime are used in sport psychology

sessions. E-mail helps not only with conversations

but with collecting data from athletes continuously,

for example, conditioning diaries (athletes can send

conditioning checksheets via e-mail). Even though

their next appointment may be far in the future,

consultants can understand and grasp athletes’ mental

conditions. Thus, consultants can be well-prepared

for their next sessions even after a long-term hiatus.

Regarding long-term support for elite athletes,

Skype or Face Time are essential for maintaining

contact and relationships with them or to provide

international service. In addition, when working with

elite athletes who have been committed to their sport

for almost their entire lives, sport psychology

consultants often naturally deal with the situation of

career transition. Numerous research exists regarding

assessment or the process of career transition for elite

athletes around the world (Wylleman and Reints,

Support Technology in Sport Psychology - Career Transition of Elite Athletes: Role of Mental Training

127

2010). Particularly, Zhang et al., (2013) demonstrated

Chinese elite athletes’ career transitions and social

mobility was associated with the alteration of the

Chinese government support system. Furthermore,

research concerning various countries’ career support

programs is also presented (Yoshida et al., 2006,

2007). Importantly, Japan Olympic Committee (JOC)

started a support program for elite athletes in 2004 as

a Second Career Project, distributing enlightening

pamphlets, starting up an information website, and

holding seminars. Furthermore, along with

establishing a National Training Center in 2008, the

Career Academy Project began. In this project,

national members receive guidance, seminars,

exchange meetings with former and current

Olympians, and individual counseling. Currently,

JOC has expanded employment support in the project

(Japan Sport Council, 2014).

From the understanding of various countries’

movements as mentioned above, career transition is a

realistic, serious concern for elite athletes. Thus, the

process of career transition very often emerges as a

main theme in sport psychology sessions.

This study introduces how support technology is

related to the field of sport psychology. One of the

cases regarding the use of Information

Communication Technology (ICT) is described in

detail as qualitative research concerning elite athletes

facing career transition.

2 METHODS

A case-study approach was used for analysing the

data.

There are many different types of qualitative

approaches in research fields (Merriam, 2009). The

case study approach is one of them, and is utilized in

many different fields such as psychology, sociology,

political science, anthropology, social work,

business, education, and nursing, et cetera (Yin,

2014). When a researcher decides which research

methods to use for a study, types of research

questions are the key factors. Yin argues that when

research questions center on the “how” and “why” of

single individual(s) or group(s), an occurrence of an

event(s), or a program(s), it is appropriate to use case

study. Simply, the case-study approach is a

qualitative in-depth study of a particular situation

compared with a quantitative, sweeping statistical

survey.

2.1 Two Single Cases: Career

Transition

Both participants performed individual scoring

sports. Each athlete’s final goal was the Olympics,

though Case A had already moved on to his second

career after 18 years of trying. Case B once left from

competing after the second Olympics then came back

to compete in nearly 2 years (More details in Table 1).

Table 1: Demographic Information.

Case A Case B

Age 29 Age 28

Male Female

Representing country

USA

Representing country

Japan

18 years of training 22 years of training

14 years as

national member

13 years as

national member

Highest achievement

2007 World Championships

Highest achievement

2008 Olympics Final

2012 Olympics

Mental training

1 1/2 years: 57 sessions

(Follow up sessions)

Mental training

1 year: 18 sessions

(Follow up sessions)

2.2 Data Collection

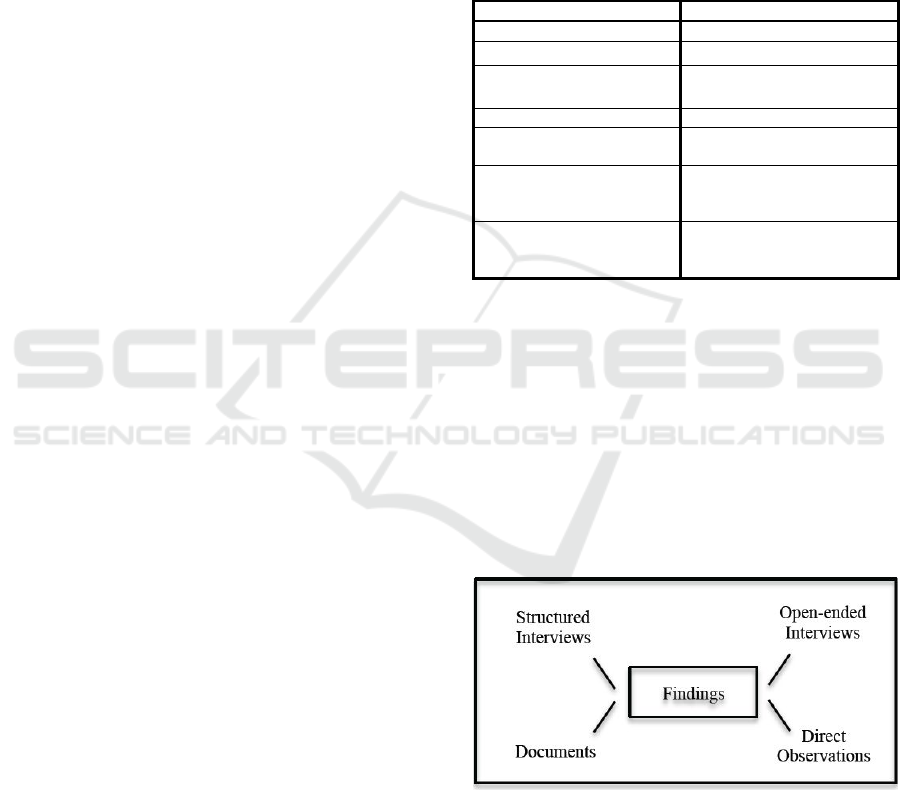

ICT tools were used to collect data. Evidence came

from multiple sources. The data were collected from

structured and open-ended interviews conducted

through Skype (both athletes were abroad during this

research). In parallel, documents from mental training

sessions (including both in-person and Internet-based

interventions) were absolutely essential. In addition,

direct observations from sessions, interviews, and

competitions were utilized (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Convergence of multiple sources of evidence.

2.3 Data Analysis

Logic Models (Wholey, 1979) was utilized for data

analysis to specify and operationalize a composite

chain of the events. The events continue cause and

effect patterns towards different stages. Therefore,

icSPORTS 2015 - International Congress on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support

128

the use of logic models consists of fitting empiric

observation of events to theoretically predicted events

(Yin, 2014). After the data analysis was complete, the

findings were explained both in writing and tabulated

as figures. In this study, various data from two single

cases was analyzed by multiple units, so that research

design was called embedded, multiple-case design.

3 RESULTS

[Case A]

・ Two open-ended interviews were conducted in

2008

・ A structured interview was conducted in 2015

When he couldn’t make the Olympics in 2008, he

strongly held an emotion of distrust of judges right

after the selection. He also had negative feelings

about new revised rules towards Olympic selection.

His primal needs were to face and accept his emotions

then handle the reality of results. Surely, he needed

time to release his chagrin and frustration thorough

talking to the consultant. At the same time,

surprisingly, he expressed determinate motivation

and a mind of revenge for the next Olympics.

Regarding the selection procedure, he positively

perceived that there was a big chance of rule revision.

He had already started mentioning specific long and

short-term goals to fight for four more years, even

searching for the next training base after graduating

from university within a year. He seemed to have

various options.

Most importantly, he had solid, social support

from significant people around him. First of all,

advice from his father (his coach) influenced and

guided him profoundly. He had opportunity to listen

to Olympic medalists’ experiences as role models and

mentors. From another perspective, he had attended a

worldwide, well-known, prestigious university.

Therefore, he saw his seniors and teammates become

very successful as professionals in their second career.

In that kind of environment, he had often heard that

sport is not everything and an athletic career is just a

part of your life. In addition, as part of the US

educational system, he received an internship

opportunity as a member of society during his school

life. He explained the experience as a time and

opportunity to see himself as “new me”. Through the

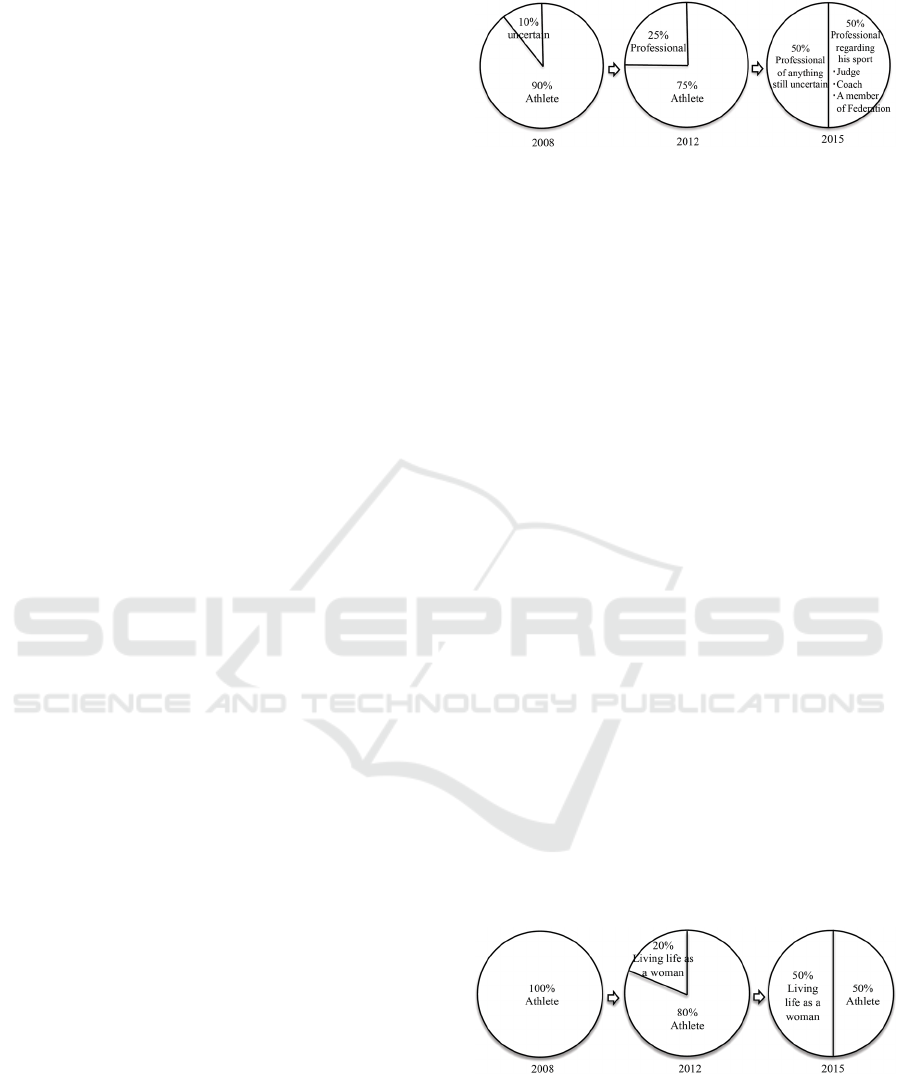

life event, he started developing dual identities at the

time of still being an elite athlete. Figure 6 shows his

transition of personal identity.

Figure 6: Case A’s transition of personal identity.

[Case B]

・ Three open-ended interviews were conducted in

2012

・ A structured interview was conducted in 2015

After the second Olympics in 2012, Case B once left

her sport. Soon after the Olympics, she felt lonesome

and empty for long period of time. Her emotional

state was unstable in and outside of the sessions.

Behind the situation, she carried too much concern

and seemed to be struggling with burnout. The major

issue was to find a training base and personal coach.

Due to the limited places for her sport throughout the

country, it was very hard to find a secure training base

or personal coach. Another issue was the physical

burden of her particular discipline. Therefore, she

dithered in transferring to a different discipline. She

was searching the possibility of remaining as a top

athlete in her sport. Financial insecurity further

worsened the situation. Last but not least, she was

stressed out by coping with being both an elite athlete

and student.

She explained that she never had the time and

opportunity to think about a second career. She even

felt a sense of sin in focusing on something else other

than her sport only. Not surprisingly, she was not able

to imagine or desire becoming “a different person”

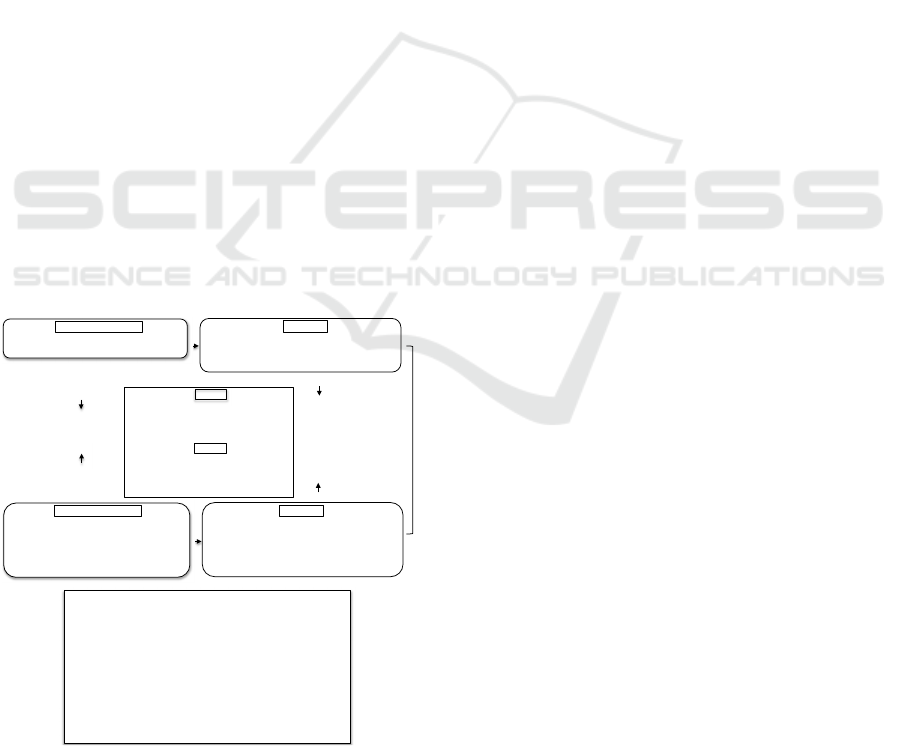

after her athletic career. The time of absence from her

sport became the origin of the development of her

new identity. Figure 7 shows her transition of

personal identity.

Figure 7: Case B’s transition of personal identity.

Two things made her situation change for the

better. One is that she was chosen as a target athlete

in a national support project. The project made it

possible for her to move overseas training bases. With

financial support, she was able to train with foreign

Support Technology in Sport Psychology - Career Transition of Elite Athletes: Role of Mental Training

129

national teams and coaches. Currently, she looks

forward to the next Olympics.

4 DISCUSSION

Blumenstein and Lidor (2007, 2008) argued the

importance of psychological support in the Olympic

year that is the final stage of the 4-year program for

both athletes who had already met the Olympic

criteria and those athletes who failed to meet the

Olympic criteria. In this study, there were also

obvious needs from an athlete (case A), who couldn’t

make the Olympics, concerning his career transition.

In this case, consultants can help with the process of

sorting out athletes’ feelings on this subject.

The next step could be helping the decision-

making process. Whether the athletes continue their

sport or retire from their sport, this decision will be

crucially important in the events which mark the

stages of their life.

As case B results showed, having no identity other

than an elite athlete affected her emotional state

negatively, even though she still has the physical

potential to compete at the next Olympics. She was

stacked with confusion, frustration, and depression,

and she took a long period of time to recover.

Therefore, most importantly, consultants need to help

with the process of developing a new identity at the

final stage of mental training in elite athletes’ career

transitions because athletic careers do end eventually.

Figure 8: Consultants’ possible interventions as the final

stage of mental training in elite athletes’ career transition.

During the career transitions of elite athletes,

some other important aspects come to the forefront.

Solid social support (social skills training), role

models and mentors (family members, coaches,

former Olympians, et al.), and dual career

experiences will lead to a successful career transition.

Additionally, introducing national support projects

such as career support programs might be a helpful

tool for them.

Stages of career transition and possible

interventions are presented in figure 8.

5 CONCLUSIONS

From the results of this study, the role of a sport-

psychology consultant, in the ultimate stage of mental

training, is essential for the smooth career transition

of elite athletes.

At first, for both the athletes who make the

Olympics and those that don’t, sport psychology

consultants can help (need to help) their emotional

process. Although, when an athlete’s dream of

making the Olympics comes true, the time after this

first Olympics might be the time when consultants

need to pay special attention to whether the athlete

moves towards the next Olympics (possible burnout)

or moves on to a second career.

Moreover, the needs of athletes for career

transition support come from different angles. Thus,

sport psychology consultants are required to have a

wide range of flexibility, knowledge, and experience

skills. When working with elite athletes, winning or

losing is one of the most important aspects, especially

regarding the Olympics. However, they have unique

needs because of their long athletic careers.

Consultants definitely need to remember that their

career transitions are equally important. The role of

mental training certainly comes into play here.

This information might be useful for both sport

psychology consultants and coaches when their

athletes are struggling with career transition,

especially at the elite level. In the case of not having

a sport psychology consultant on their team, coaches

need to fill the role of advisor or counselor for their

athletes.

Lastly, the good use of ICT permits worldwide

long-term interventions at any location for elite

athletes. It also improves

various aspects of data

accumulation.

[Any time]

①Provide the opportunity to learn dual career concept for elite athletes

②Provide an opportunity to think, imagine, and discuss about career transition

③Provide an opportunity to meet role models for them

[Right after the Olympics]

④Help athletes put their experience and thoughts into words

⑤Provide coping skills for emotional process (as needed)

⑥Help with the decision-making process

[Continuing the athlete’s career]

⑦Help get through pos sible burnout after huge amount of energy loss (help get back their energy)

⑧Help find as many resources from support projects as possible (i.e., national support project by

government) and work together (i.e., prepare application or interviews)

⑨Mental training for the next Olympics

[Move on to second career]

⑩Help extend social network

⑪Social skills training (communication skill training, etc.)

⑫Follow up sessions

Sport Psychologists : Possible Interventions

④⑤⑥

⑩⑪⑫

⑦⑧⑨

①

②

③

Tools offering career support

Case B

・Solid social support

→His father (his coach)

→Olympic medalists as mentors

・Dual career (job / sport)

・Develop a new identity apart from being an elite athlete

・National support project

・New environment

(secure training base and personal coaches)

・Technical improvement in he r sport

(acquisition of a new skill)

Case A

・Burnout (after Olympics)

・Physical decline / burden

・Feelings of loneliness and emptiness for an extended period

・Finding a secure training base and personal coaches

・Transferring to a different discipline

・Financial insecurity

・Coexistence as an athlete and a student

Concern / Difficulty

Case B

Primal:

・Help for the emotional process (coping skills)

・Help with the decision-making process

・Financial support

Subsequent:

・Social support for both sport and school situations

・Mental training for how to deal with overstressing at competition

Needs

Case B

・Injury

・Physical decline / burden

・Emotional Process (missed Olympics)

Concern / Difficulty

Case A

Primal:

・Help for the emotional process of facing, accepting, and

handling the reality of the results

Subsequent:

・Opportunity for a dual career (job / sport )

Needs

Case A

icSPORTS 2015 - International Congress on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support

130

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Japan

Society for the Promotion of Science Fellows.

REFERENCES

Blumenstein, B. & Lidor, R., 2007. The Road to the

Olympic Games: A Four-Year Psychological

Preparation Program. Athletic Insight, 9(4), pp. 15-28.

Blumenstein, B. & Lidor, R., 2008. Psychological

preparation in the Olympic village: A four-phase

approach. International Journal of Sport and Exercise

Psychology, 6(3), pp. 287-300.

Galloway, S. M., 2011. The effect of biofeedback on tennis

service accuracy. International Journal of Sport and

Exercise Psychology, 9(3), pp. 251-266.

Gould, D. & Maynard, I., 2009. Psychological preparation

for the Olympic Games. Journal of Sports Sciences,

27(13), pp. 1393-1408.

Hayden, E. W., 2008. Efficacy of an ambulatory

biofeedback device on marksmanship: A preliminary

investigation. Unpublished manuscript, University of

Akron, Akron, OH.

Japan Institute of Sports Sciences, 2012. Annual report

2012. [Online] Available at:

http://www.jpnsport.go.jp/jiss/Portals/0/info/pdf/nenpo

u2012.pdf. [Accessed 20 June 2015]

Japan Sport Council, 2014. Report of dual career research

2014, Tokyo: Japan Sport Council.

Merriam, S. B., 2009. Qualitative research: A guide to

design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: John

Wiley & Sons, Inc.

McCann, S., 2008. At the Olympics, everything is a

performance issue. International Journal of Sport and

Exercise Psychology, 6(3), pp. 267-276.

Muench, F., 2008. The Portable StressEraser Heart Rate

Variability Biofeedback Device: Background and

Research. Biofeedback, 36(1), pp. 35-39.

Paul, M. & Garg, K., 2012. The Effect of Heart-Rate

Variability Biofeedback on Performance Psychology of

Basketball Players. Applied Psychophysiology and

Biofeedback, 37(2), pp. 131-144.

Sasaba, I. & Sakuma, H., 2014. Effectiveness of

Biofeedback on Breathing Exercise as part of Mental

Support for Elite Athletes. Japanese Journal of

Biofeedback Research, 41(1), pp. 27-36.

Wholey, J., 1979. Evaluation: Performance and promise.

Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

Wylleman, P. & Reints A., 2010. A lifespan perspective on

the career of talented and elite athletes: Perspectives on

high-intensity sports. Scandinavian Journal of

Medicine & Science in Sport, 20(2), pp. 88-94.

Yin, R. K., 2014. Case Study Research: Design and

methods. 5

th

ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE

Publications.

Yoshida, A. Saeki, T. Kouno, I. Tashima, T. Kiku, K. &

Ohashi. M., 2006. A Study of Second Career

Establishment for Top Athletes (No.1). Bulletin of

Institute of Health and Sport Sciences, University of

Tsukuba, 29, pp. 87-95.

Yoshida, K. Kono, I. Yoshida, A. Kiku, K. Soma, H.

Miyake, M. Katakami, C. & Saeki, T., 2007. A study of

Second Career Establishment for top athletes (No.2)

The cases of Canada, Australia, Germany and France.

Bulletin of Institute of Health and Sport Sciences,

University of Tsukuba, 30, pp. 85-95.

Zhang, F. Qiu, J. & Zhu, W., 2013. Career transitions and

social mobility among Chinese elite athletes. Asian

Journal of Exercise & Sports Science, 10(2), pp. 24-35.

Zizzi, S. J. & Perna, F. M., 2002. Integrating Web Pages

and E-mail Into Sport Psychology Consultations. The

Sport Psychologist, 16(4), pp. 416-431.

Support Technology in Sport Psychology - Career Transition of Elite Athletes: Role of Mental Training

131