Knowledge Artifacts: When Society Objectifies Itself in Knowledge

Andrea Cerroni

Dpt. of Sociology and SR, University of Milan-Bicocca, Milan, Italy

Keywords: Objectified Knowledge, Knowledge-society, Sociology of Knowledge, Knowledge Circulation, Social

Epigenesis.

Abstract: The paper deals with knowledge artifacts as knowledge socially objectified. A typology of knowledge is

considered, comprising forms (intellectual, practical, objectified); families (knowings, acquaintances,

acknowledges) and kinds (for objectified knowledge: encapsulated, environments, symbols). A model for

knowledge-society (as a new societal layer sedimenting over precedent ones) is also introduced in four logic

phases (generation; institutionalization; diffusion; socialization) in order to show the mechanisms for its

production.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the term ‘knowledge’ we make reference to

many different ‘things’. In this paper I will deal with

the concept of knowledge artifact, which has been

recently reconsidered as a multidisciplinary concept

to focus on in the intersection between informatics

and the humanities (Cabitza and Locoro, 2014). To

this aim, I will treat knowledge artifacts as

objectified knowledge (tangible forms), after Marx

(1858), i.e. one of the three forms in which

knowledge comes under own direct disposal, the

others two forms being practical knowledge

(resident within a large but definite social species)

and intellectual knowledge (the explicit or the taken-

for-granted forms widely shareable and so the only

considered by the Enlightenment epistemology).

However, a whole typology (Cabitza et al. 2014;

Cerroni to be published) comprises these three forms

of knowledge directly acquired (the family of

knowings) and other forms gained in two other ways

of acquiring knowledge: through a social network of

acquaintances and through external and internal

acknowledgements. Few words for the last two will

be enough for our ends. On one side, the family of

acquaintances comprises knowledge I can more or

less easily reach through my own social network,

similarly to the social capital. On the other side, the

family of acknowledgments comprises knowledge

capacities attributed to me by others, maybe just

stuck, and which, in the long run, become

acknowledged as my own conscious knowing.

Let us now focus on objectified knowledge.

2 ARTIFACTS AS OBJECTIFIED

KNOWLEDGE

This is a wide species of knowledges, indeed.

A first kind is encapsulated in physical objects:

food made in a well-established gastronomical

tradition, objects made by an artisan or an industry

(e.g., a compass), tools for making either other

objects (e.g., an assembly robot) or other knowledge

in some form (e.g., a word processor) etc. The value

we can enjoy using such objects comes without

necessarily having to de-capsulate the knowledge

therein. In effect, sailors have been using compass

far before having developed a theory of magnetism.

We do not even need neither to know the recipe in

order to enjoy good food nor to be a program

developer in order to write a good book using a

word processor, even if we should have some benefit

in being a great chef or a good a programmer. When

we do not have the expertise to de-capsulate the

knowledge inside our object, however, we have to

rely on some expert, quite often anonymous

agencies, with a more or less blind trust. The endless

fiduciary chain thus born links our daily life with

huge other people so that the most educated and

connected people of the entire human history are by

far the less suited to survive by their own means to

the challenges of common daily life (this is the

paradox of the knowledge society). The reason for

such situation is obvious: knowledge has been

growing faster than our personal education and our

acquaintances. While life-long learning is an answer

Cerroni, A..

Knowledge Artifacts: When Society Objectifies Itself in Knowledge.

In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2015) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 429-435

ISBN: 978-989-758-158-8

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

429

to the need of education, new media are an answer to

the need of social cooperation: knowledge has an

unbeatable cooperative and not simply additive

nature.

A second kind of objectified knowledge is not

encapsulated inside objects, but rather aroused by

cultural/artistic goods or environments as paysages.

When we enjoy seeing, hearing or ‘living’ a piece of

art we realize that knowledge is therein and we have

the opportunity to use it for future uses or, possibly,

creations, too. This knowledge educates our esthetic

sense, supplies us with the comprehension of a

singular author or historical epoch, a human

situation and much more: we can introject it as our

own (cognitive, relational, emotional) system-of-

reference. The Stendhal syndrome, also named

Florence syndrome or hyperkulturemia, can be

considered as a sort of information overload,

occurring when we do not have the time and/or the

opportunity to metabolize it within our own

knowledge assets. Think of visiting artistic towns

such as Florence or closed locations so dense in

knowledge as Sistina Chappelle in Vatican City. In

such cases, clearly extremes of a continuous (wide

open paysages – closed environments), knowledge is

what transforms stark matter in an artifact, a piece of

marble in a Michelangelo’s Prigione, a natural

landscapes in humanized paysages as a wild lagoon

into the lagoon-town of Venice, or the experience

with a pile of software & hardware components into

a pretty new life experience with the electronic

device I just bought to my children. We can benefit

from such knowledge through a simple sensorial

‘immersion’; however, the more we know before,

the more we can ‘extract’ from it in view of our own

interest, of course. Similar argumentations can be

made for artificial environments, where

hyperkulturemia is frequent in own experience while

surfing within the web, moving across multiple

electronic devices more or less interconnected each

other and connecting within social networks with

other people.

Lastly, the third kind of objectified knowledge

collects peculiar aspects of social symbols, such as

religious ones, nation flag, or any other artifact with

symbolic value. In these cases knowledge is not to

be found inside the stark object, but it is shared

within a social community acknowledging the

symbolic meaning while acquiring it as (part of)

own identity. However, everything has (can have) a

symbolic component, for some people. Even an

equation may become an icon (e.g., E=mc

2

) being

tattooed on the back. A gesture may become a social

practice of mutual identification with hierarchical

and/or strong political meaning (e.g., raising the

right hand to the cap; outstretching the right arm;

raising a clenched fist, the right rather than the left,

colored rather than not). It is particularly interesting

the case of concrete objects and other artifacts.

Think of dozens of town named Venice in Northern

and South America, the European ‘Venices of the

North’, Asian ‘Venices in the Orient’: we recognize

both symbolic value addition to real towns and a

‘disneyfication’ of a symbol-town (Settis 2014). The

same transformations occur to any consumer object

through fashion, fads and foibles. Sometimes, the

same occurs to artistic or intellectual production, as

well. All of these families are made of knowledge

tacit(ated) (Polanyi 1969); they are dead knowledge

(cf. dead/living work in Marx 1858), explicit to

someone but not (necessarily) to the specific user,

who, instead, has to work creatively (consciously or

not) in order to bring it back to life as a living

knowledge. Moreover, a commodification of

knowledge can either enhance the knowledge-value

of an artifact or wasting it, definitively.

As we see, the net result of creating and using

knowledge depends on its circulation, from the first

stage of innovation to its common use and, possibly,

its abandonment. Indeed, this conception of

knowledge as a shared understanding is in close

connection with the three Indo-European roots of the

Latin word cognoscentia (cfr. Eng. cognizance; It.

conoscenza; Fr. connaissance; Sp. conocimiento;

Port. conhecimento), from which the English

‘knowledge’ comes. They are: (1)*kom: Lat. cum

meaning together-with and/or near-to; (2) *gn: Eng.

to Know meaning a savoir; (3) *sk: Lat. scire, Eng.

sced, meaning to distinguish.

3 EPIGENETIC KNOWLEDGE

CIRCULATION (EKC)

In spite of the growing attention that has been

devoted to knowledge outside philosophy in a

growing number of disciplines during the last

decades, the only theoretical model relevant for

applications in innovation studies still is the

Nonaka’s model of knowledge (e.g., Nonaka and

Takeuchi 1995). We don’t consider the ‘Triple helix

model’ (e.g., Etzkowitz, Leydesdorff 1995), another

model once proposed, as it is not able to take into

account the knowledgeable citizens that are now

having growing attention from innovation studies

and science production and communication (e.g.,

Wynne 2007, Destro Bisol 2014, Austen et al. 2014),

too.

KITA 2015 - 1st International Workshop on the design, development and use of Knowledge IT Artifacts in professional communities and

aggregations

430

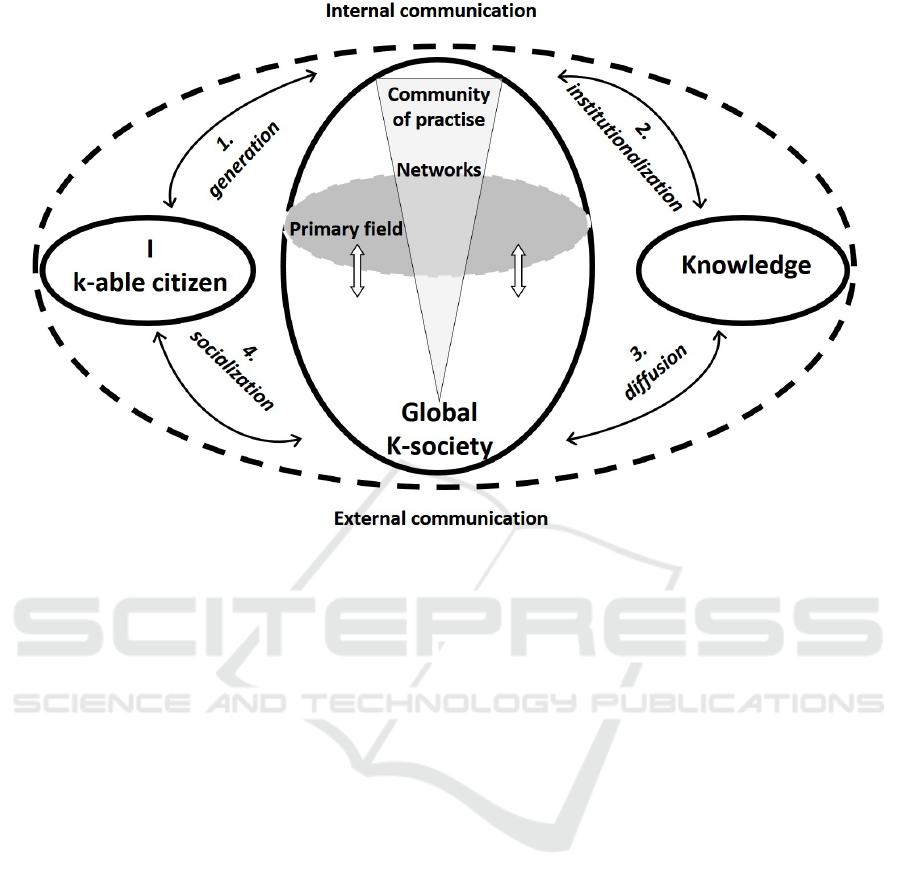

Figure 1: The circulatory model.

Knowledge-society has become a locus within the

analysis of the contemporary society (e.g., Richta

1966; Bell 1967; Masuda 1981; Stehr 1994; Castells

1996; European Commission 1997; World Bank

1999; David, Foray 2003; European Commission

2007; Rohrbach 2007; Fagerberg et al. 2012),

sometimes confused with information society, but

always with big changes envisaged both for

organizations (e.g., Nonaka, Takeuchi 1995; Stewart

1997; Davenport, Prusak 2000) and science

community (e.g., Gibbons et al. 1994; Dasgupta,

David 1994).

However, it is better to think about knowledge-

society as a layer of contemporary society,

functioning through the mechanism of producing

knowledge by means of knowledge, with surplus of

knowledge (Cerroni 2006; Cabitza et al. 2014;

Cerroni to be published). Of course, such knowledge

is never ‘pure’, but may be ‘developed’ as a linear

combination of its components, as already seen,

within a multidimensional space of ideal-types of

knowledge.

Then, we can now look at the knowledge-society

as a new social layer added via knowledge

productions, sedimented over pre-existing layers (in

primis, industrial-society). We call such a way of

development social epigenesis, in close analogy to

recent epigenetics within biological science (e.g.,

Rose, 2005).

Moreover, if the function of sharing knowledge

is communicative (and cooperative), then, when

there is no communication, there is also no

knowledge, strictly speaking, although there may be

conspicuous personal understanding hidden into a

drawer (e.g., artisanal know-how).

To articulate a model for social production of

knowledge artifacts, we can now recall the three

main logical components of sociality: individuals,

knowledge, and society in the middle between the

two, with the role of medium. Individuals are more

and more understandable as knowledgeable citizens,

empowered in knowledge and vested of public

rights/responsibilities. Society comprises the

primary field of those people strictly cooperating

together (micro-society) and also the society at large

(macro-society). Communities of practice (Wenger,

1998) intersect the primary field via the strong

informal ties of a Gemeinschaft developed around

knowledge practices. Knowledge comprises any

form of heritage, as considered before.

4 A CIRCULATORY MODEL FOR

SOCIAL PRODUCTION

A functional model of circulation within the global,

knowledge-society now considers interactions

Knowledge Artifacts: When Society Objectifies Itself in Knowledge

431

between the individuals level and their societal

environment and between this environment and a

collective heritage (collectively named knowledge),

and vice versa. In doing so, we obtain four-phase

model as shown in Figure 1.

Clearly, the four phases are just logically

distinguishable, neither in re nor in time (as they are

in other models). Let us now look a little closer to

the four phases, focusing on knowledge artifacts.

4.1 Generation

Generation (G) comprises production of new pieces

of knowledge, i.e., those processes in which the

individual provides knowledge to its own knowledge

institution (team, community or formal

organization). An artifact is partly due to true

innovative processes (ideation, action or

construction) but also to novel combinations of

already available knowledge of any kind. Anyway, it

is important to draw attention from (actual and

potential) publics of an innovation so as to enhance

the possibilities of future innovations.

4.2 Institutionalization

The institutionalization (I) of knowledge consists in

the identification, selection, coding, validation,

corroboration, design and settling of the local

knowing community in order to share knowledge

claims both internally and with the wider society. A

knowledge artifact is, then, acknowledged by a

community and/or the society at large, as

meaningful. The role played by institutions is in

reducing variants coming from the generation phase

and also adding a public value.

4.3 Diffusion

The diffusion (D) of knowledge so institutionalized,

however, is not a mere transfer of something which

is already pre-formed, but it is rather the

‘percolation’ through the wider society. This process

makes a knowledge artifact accessible to the active

involvement of other subjects –the community

members, the consumers – possibly giving rise to

new and different institutionalizations (artifacts

and/or other knowledge kinds). A participatory

decision-making and creative uses of this knowledge

by workers, customers/users and citizens creates a

shared value (open innovation: Chesbrough 2003).

Knowledge artifacts, then, may diffuse in their

explicit content, in their practices and in their

objectified knowledge. The intellectual knowledge

diffuse through the language of communication. The

practical knowledge diffuse through the social

exchanges within the daily life. The objectified

knowledge diffuse as objects (material and

symbolic) circulating within society.

Anyway, the role played by other individuals is

de facto a creative production rather than passive re-

production, so stimulating a ‘spontaneous’

innovation.

4.4 Socialization

Through socialization (S) knowledge is passed

through markets (commercialization), social strata

(communication strictu sensu) and generations

(education and learning), while being more or less

legitimated by public opinion, and eventually

forensic practices (e.g., Jasanoff 1995; Lynch 2008)

and other regulations. Of course our use of the term

socialization is quite different from Nonaka’s one,

being in compliance with the use of sociology. In

this phase, knowledge artifacts get internalized and

acquire a normative value, possibly becoming a

reference both publicly sanctioned and privately

interiorized, e.g., as a recognized artistic object, a

technological forerunner, a must.

Knowledge artifacts, then, end up raising

expectations, and dissatisfactions, too, along a

characteristic hype curve, out of which they become

either art or rubbish, an outdated relic or a classical

reference.

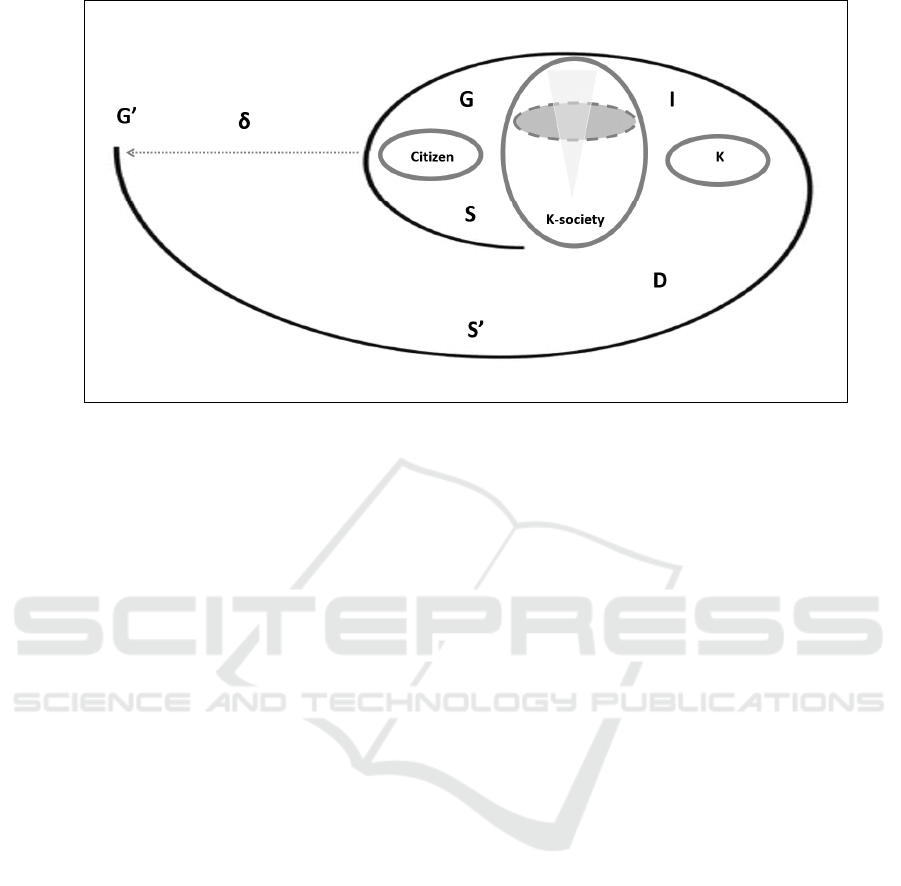

Innovation (δ), in the end, emerges from a

(logic) cycle as shown in Figure 2, where it is

indicated that, at the end of a clockwise cycle, the

available knowledge increases and spiralizes

becoming socially pervading.

We should also consider as a counter-clockwise

cycle either the anticipation as pro-jected effects

while designing or the shared culture intro-jected by

actors and/or institutions. However, the model, as

any model, is just an epistemological tool for

making understanding and experience, not a

metaphysical mirror for ‘Reality’.

The stratification of knowledge layers (made of

knowledge of any kind) makes the innovation

process path-dependent. If this process takes place

when the conditions of the previous levels are not

equal, it may end up amplifying these uneven

conditions. Circulation does not brings about

equality in itself, but rather rises divides in access

(primary) and, still more subtly, in use (secondary).

Indeed, it enhances pre-existing divides to which

adds its specific divides, in absence of a proper

governance of a public good.

KITA 2015 - 1st International Workshop on the design, development and use of Knowledge IT Artifacts in professional communities and

aggregations

432

Figure 2: The model for innovation.

5 CONCLUSIONS

It should be clear that the distinction into three forms

of knowledge correspond to the three dimensions

abovementioned. The ideal-type of intellectual

knowledge is the most close to the more vast and

lasting heritage of human genus (e.g., Pythagoras’s

theorem, Homer’s Iliad etc.). The ideal-type of

practical knowledge is shared by many individuals

of some generations within a particular social form,

historically and geographically well-delimited. The

ideal-type of objectified knowledge is confined to an

object (or environment), directly perceivable

through the senses and strictly defined within space

and time.

In the end, we should deal with knowledge as a

multidimensional space described through a 3x3x3

matrix of ‘pure states’: three dimensions

(individual/delimited, social/aggregated,

cultural/wide), three forms (intellectual, practical,

objectified) and three families (knowings,

acquaintances, acknowledgements). Here we also

noted three kinds within objectified knowledge. In

the more general case, however, knowledge appears

in a ‘mixed state’ that we can develop as a peculiar

series of ‘pure states’ (ideal-types).

We noted that knowledge-society can be thought

as a process of producing knowledge through

knowledge; however, we have also to observe that

such process, not only doesn’t deteriorate the

knowledge that is used, but it generate new

knowledge that can be ‘externalized’, and a surplus

of knowledge ‘internalized’ by the users, too. If I use

more times the ‘same’ knowledge (e.g., Pythagoras’

theorem, the compass) I augment my own capacity

to extract value from it: this is the meaning of know-

how. If others use it, and a circulation process is

active, everybody will benefit of such added value

(we now have a better Euclidean geometry than

Pythagoras or Euclid themselves; we have more

refined uses of a compass and also better ‘compass’

then Chinese had over 1000 years ago). The process

guiding knowledge-society, then, is self-catalytic if

and only if a knowledge circulation is guaranteed.

This is the reason why we have to deal with

knowledge as a (global) public good (Callon 1994,

Stiglitz 1999), settling conditions to stimulate an

active, wide cooperation without exclusions, in order

to let knowledge itself flourish. In our previous

analysis it means to go beyond the digital divides of

first order (technology access) empowering each

citizen’s knowledge capital. In other words, it means

to enhance the diffusion of already available

knowledge (knowings), to let proliferate the social

opportunities of knowledge exchange

(acquaintances), and, to use a couple of sociological

concepts, to lower the symbolic violence (Bourdieu)

onto citizens while enhancing their capability of

sociological imagination (Mills) (acknowledge).

Lastly, we see that knowledge artifacts are cases

of knowledge that is objectified by and within a

collective agent: the subject of (co)production being

shortly society.

The case for Ict artifacts deserves a deeper

insight. They are, indeed, (a) a product, (b) a

process, and (c) an enabling technology.

Knowledge Artifacts: When Society Objectifies Itself in Knowledge

433

(a) Ict artifacts are products always having a

material basis, even as material machinery, and so

they are vehiculated by a general circulation of

knowledge.

(b) However, Ict is also a process of

communication, i.e., in our model, itself circulation

in all its phases. They enhance the capacity to

institutionalize knowledge, making more visible and

manageable the knowledge generated and act on the

diffusion phase both expanding modalities and

empowering participants. However, they also have

effect onto socialization both in reaching people and

in giving them new opportunities to generate new

knowledge.

(c) Moreover, Ict is a vehicular technology,

enabling any knowledge to fill in our perceptive

experience, empowering, enhancing and virtualizing

presences in it. Rather than to a dematerialization,

our lives are undergoing to a re-materialization

driven by new technologies. Apart from Ict, other

vehicular technologies are biotechnologies and

nanotechnologies. Through such vehicular

technologies, not only is the intellectual knowledge

enabled to enter any object, but also practices (from

automation to web interactions).

As far as possible concrete uses of the concepts

and models here introduced, suggestions can already

be seen in various areas of research, such as

participative informatics (Cabitza et al. 2014; cfr.

Carroll, Rosson 2007), agricultural knowledge and

innovation systems (Di Paolo and Vagnozzi 2014;

cfr. EU SCAR 2012), open science and citizen

science prospects (e.g., Destro-Bisol et al. 2014; cfr.

Austen et al. 2014).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank three reviewers for their warm

acceptance of a previous version of the present paper

and for useful suggestions to improve it.

REFERENCES

Austen et al. (2014) White Paper on Citizen Science for

Europe. SOCIENTIZE Project. Brussels: European

Commission

Bell D (1967) ‘Notes on the Post-Industrial Society’. The

Public Interest, 7: 112-118.

Cabitza, F., & Locoro, A. (2014). “Made with

Knowledge”: Reporting a Qualitative Literature

Review on the Concept of the IT Knowledge Artifact.

In Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and

Knowledge Management (pp. 571-585). Springer

International Publishing.

Cabitza F et al. (2014) ‘The Knowledge-Stream Model - A

Comprehensive Model for Knowledge Circulation in

Communities of Knowledgeable Practitioners’. In

KMIS 2014: Proceedings of the 6th International

Conference on Knowledge Management and

Information Sharing. Rome, Italy, October 21-24

2014. Scitepress.

Callon M (1994) ‘Is Science a Public Good?’ Science,

Technology, & Human Values, 19 (4): 395-424.

Carrol JM, Rosson MB (2007) ‘Participatory Design in

Community Informatics’.

Design Studies, 28(3):243-261

Castells M (1996) ‘The Rise of the Network Society’, in:

The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture

(I). Oxford: Blackwell.

Cerroni A (2006) Scienza e società della conoscenza.

Torino: Utet.

Cerroni A (to be published) ‘Reconsidering Knowledge

for a Sociological Understanding of the Knowledge-

Society’.

Chesbrough HW (2003) Open Innovation: The New

Imperative for Creating and Profiting from

Technology. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School.

Davenport TH, Prusak L (2000) Working Knowledge:

How Organizations Manage What They Know.

Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Dasgupta P, David PA (1994) ‘Toward a New Economics

of Science’. Research Policy, 23: 487-521.

David PA, Foray D (2001) An Introduction to the

Economy of the Knowledge Society. Discussion paper

series. Oxford University.

Destro Bisol G et al. (2014) ‘Bridging Perspectives on

Open Science: A Report from the Meeting “Scientific

data sharing: an interdisciplinary workshop”’.

International Journal of Anthropology, 92: 179-200.

Di Paolo I, Vagnozzi A, eds. (2014) Il sistema della

ricerca agricola in Italia e le dinamiche del processo di

innovazione. Rome: Istituto Nazionale Economia

Agraria.

Etzkowitz H, Leydesdorff L (1995) ‘The Triple Helix of

University-Industry-Government Relations: A

Laboratory for Knowledge Based Economic

Development’. EASST Review, 14 (1): 11-19.

EU SCAR (2012) Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation

Systems in Transition – A Reflection Paper. Brussels.

European Commission (1997) Towards a Europe of

Knowledge. Brussels.

European Commission (2007) Taking European

Knowledge Society Seriously. Luxembourg.

Fagerberg J, Lanstroem H, Martin BR (2012) ‘Exploring

the Emerging Knowledge-Base of the “Knowledge

Society”’. Research Policy 41: 1121-1131.

Gibbons M, Limoges C, Nowotny H, Schwartzman S,

Scott P, Trow M (1994) The New Production of

Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research

in Contemporary Societies. London: Sage.

Jasanoff S (1995) Science at the Bar. Law, Science, and

Technology in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

KITA 2015 - 1st International Workshop on the design, development and use of Knowledge IT Artifacts in professional communities and

aggregations

434

Lynch ME (2008) Truth Machine: The Contentious

History of DNA Fingerprints. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press.

Marx K (1858) Grundrisse der Kritik die Politische

Ökonomie. Moscow (1932).

Masuda Y (1981) The Information Society as

Postindustrial Society. Bethesda, MD: World Futures

Society.

Nonaka I, Takeuchi H (1995) The Knowledge-Creating

Company: How Japanese Companies Create the

Dynamics of Innovation. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Polanyi M (1969) The Tacit Dimension. New York:

Anchor Books.

Richta R et al. (1966) Civilizace na rozcestí. Prague:

Svaboda.

Rohrbach D (2007) ‘The Development of Knowledge

Societies in 19 OECD Countries between 1970 and

2002’. Social Science Information 46 (4): 655-689.

Rose S (2005) The 21

st

Century Brain: Explaining,

Mending and Manipulating the Mind. London:

Jonathan Cape.

Settis S (2014), Se Venezia muore. Torino: Einaudi.

Stehr N (1994) Knowledge Societies. London: Sage.

Stewart TA (1997) The Intellectual Capital. The New

Wealth of Organization. New York: Doubleday.

Stiglitz J (1999) ‘Knowledge as a Global Public Good’, in

Kaul, I., Grunberg, I. and Stern, M., eds., Global

Public Goods. International Cooperation in the 21

st

Century. New York & Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Wenger E (1998) ‘Communities of Practice: Learning as a

Social System’. The System Thinker 9 (5): 1-8.

World Bank (1999) World Development Report:

Knowledge for Development. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Wynne B (2007) ‘Public Participation in Science and

Technology: Performing and Obscuring a Political-

Conceptual Category Mistake’. East Asian Science,

Technology and Society: An International Journal (1):

99-110.

Knowledge Artifacts: When Society Objectifies Itself in Knowledge

435