The Misfits in Knowledge Work

Grasping the Essence with the Lens of the IT Knowledge Artefact

Louise Harder Fischer and Lene Pries-Heje

IT University of Copenhagen, Rued Langgaards vej 7, 2300 København S., Denmark

Keywords: IT-knowledge Artefacts, UC&C, Situativity, Socio-Technical Fit, Individual Practices, Knowledge Creation.

Abstract: The workplace is changing rapidly and knowledge work is conducted increasingly in settings that are global,

digital, flat and networked. The epicenter of value-creation are the individuals and their interactions. Unified

Communication and Collaboration Technology (UC&C) supports individual interactions, collaboration and

knowledge creation. The use of this technology is growing globally. In a previous study, we found that UC&C

in collocated and distributed settings, produced misfits and fits between situated enacted practice-use of

UC&C and the experienced productivity. We respond to the KITA 2015 call with this work-in-progress paper.

We apply

the IT Knowledge Artefact (ITKA)-interpretive lens from Cabitza and Locoro (2014) to a case of

knowledge workers struggling with appropriation of UC&C for creating and sharing practice knowledge. We

evaluate the framework - and discuss the usefulness of the lens in this specific setting. To further improve and

enrich, we pose questions, aiming at contributing to the communication of valuable insights informing the

design and use of future KITAs in knowledge work.

1 INTRODUCTION

Interactions between people over distance, time and

location has given rise to a new type of Information

and Communication Technology called UC&C

1

.

UC&C supports interactions, connections,

collaboration and communication, providing a

unified interface to an ensemble of IT-artefacts like e-

mails, chats, virtual meetings, presence and IP-calls

(Silic and Back 2013). Applications well known and

easy to use. When introduced though, the use is non-

mandatory; the adoption is voluntary and the

exploitation formed by individual preferences

(McAfee 2006). UC&C amplifies the horizontal

structure and creation of practice knowledge, that

otherwise is difficult to support in virtual work-

settings.

Our recent article “Co-configuration in

Interaction work” (Harder Fischer and Pries-Heje

2015) communicates on several issues with

productivity and autonomy in knowledge work, from

the individual practice-use of technology. The paper

involves a case of socio-technical misfit in an

1

Numbers are classified market data, but many and different

sources report from 30 – 65 % adoption of UC&C in

organizations on a global scale, and increasing.

organization and reveals that practice-use of UC&C

in situ is perceived as negatively influencing

community culture and minimizing the opportunities

for sharing practice knowledge. Hence, our previous

case study reveals a misfit between technology-in-

use, knowledge-practices and community culture.

Reading the call for papers for the KITA

workshop we were inspired to experiment with the

framework of IT-knowledge artefacts (ITKA) From

Cabitza and Locoro (2014) and use it as an

interpretative lens to gain new insights related to the

issues found in our previous work. Working with the

framework we experienced some challenges but also

some interesting novel insights. In this paper we

report on our experience using the framework and

invite the KITA community to discuss some of the

challenges we experienced. Hence, we evaluate the

usefulness of the framework contributing to refine

and enrich it.

Our overall aim is to minimize the negative

consequences of technology in organizations

(Harrison et al. 2007) and we believe that a useful

interpretative lens can guide analyst and designers

436

Fischer, L. and Pries-heje, L..

The Misfits in Knowledge Work - Grasping the Essence with the Lens of the IT Knowledge Artefact.

In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2015) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 436-443

ISBN: 978-989-758-158-8

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

when working with ITKA-based applications in

organizational contexts.

We believe that an interpretative lens, providing a

reification of knowledge, might be a way forward to

minimize the misfits in knowledge work. Sarker,

Chatterjee and Xiao (2013) makes an equal proposal

when promoting a view, that renewed understanding

of socio-technical fits, could be in terms of focusing

on the “I” in IS, and begin to look at the fit between

information and system (Sarker et al. 2013).

Progressing in our on-going studies of value

creation in modern knowledge work, we seek to

provide new understanding of misfits, tackling them

from a socio-technical perspective, seeing them

through the ITKA-framework as an interpretative

lens.

We strive to answer these questions: What do we

gain from evaluating UC&C as an ITKA in the

peculiar setting? Can we use the framework to

understand the design and use of this ITKA’s in other

settings? Can our experiences with the framework

reveal new insights that can enrich the interpretative

lens?

2 METHOD

This paper is a reply to the invitation in the call for

paper: “we invite other authors to apply this

framework to their cases to both validate it and

improve and enrich it, as a convenient interpretative

lens”. Thus, our purpose and contribution with this

paper is to evaluate and discuss the framework.

Ultimately, to pose questions for a future debate in the

KITA community based on our experience.

Consequently, this is not a classic paper and this is not

a classic method section. This section describes how

we have approached this endeavor. First, we must

explain our conceptual starting point.

In the out-set, we decided to experiment with how

to use the ITKA framework as an interpretative lens -

to understand our case in a new perspective. As a

starting point, we decided to follow the logic

suggested by the paper it-self and produced five

consecutive questions that could help us to categorize

and classify UC&C. The questions are out-lined in

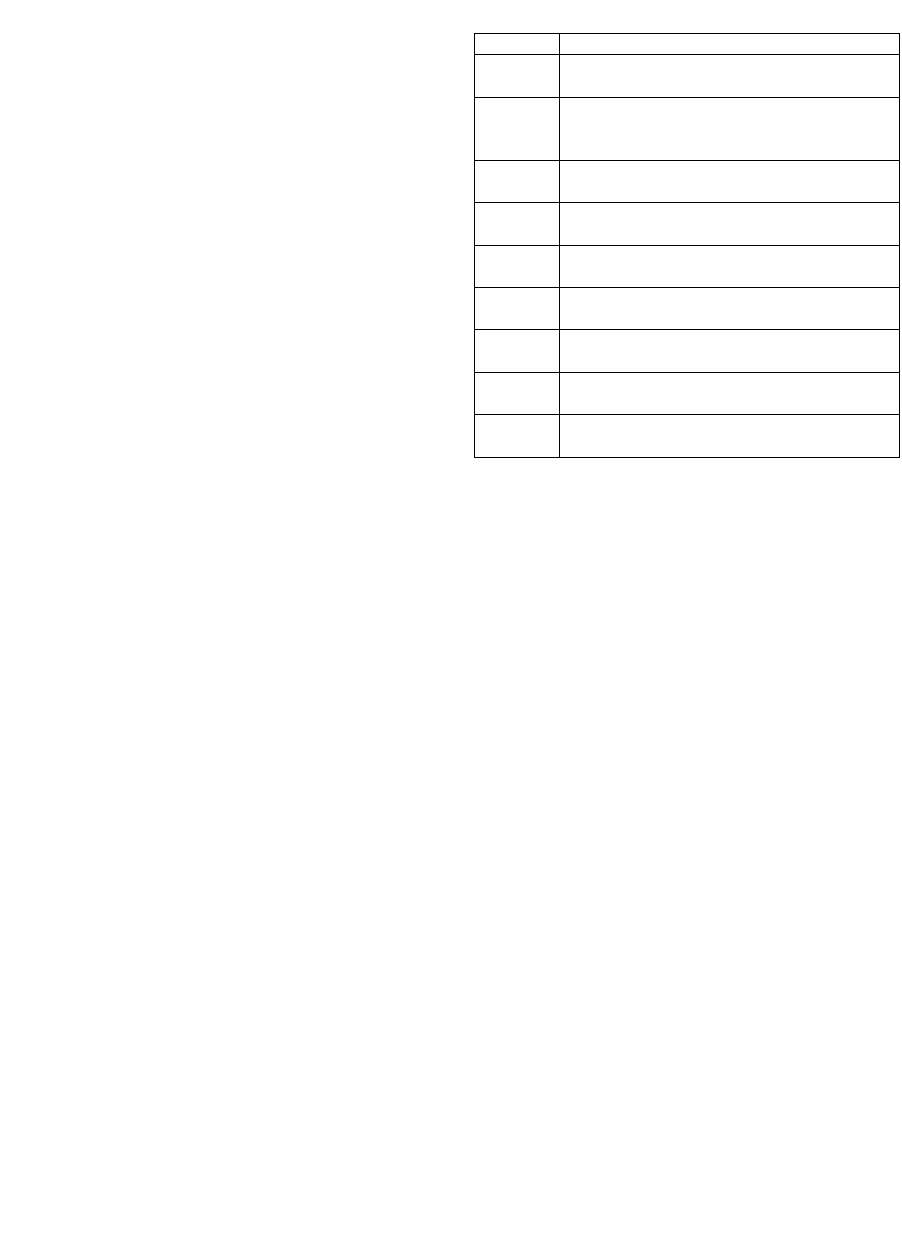

table 1.

The questions was intended as a starting point;

helping us positioning our work in the framework and

start thinking of how to use the framework. This

minor experimentation with the framework provided

the challenges and insights reported in this paper. We

have organized the paper in the following manner.

Table 1: Questions for categorizing and classifying ITKAs.

Question Five consecutive questions as the

interpretative lens

Q 1 Is UC&C an IT-artefact?

Q 2 Is the IT-artefact an IT Knowledge Artefact

(ITKA)?

Q 3 Is the ITKA socially situated or

representational?

Q 4 Is UC&C an ITKA-based application?

Q 5 Can we classify the ITKA according to the

degree of objectivity and situativity, implied

from the design input and requirement for the IT

artifact as the final out-put.

In section 3, we present our understanding of the

case, as it was prior to experimentation with the

ITKA-framework.

In section 4, we apply the framework and provide

the answers to the five questions defined in order to

experiment with the ITKA-framework.

In section 5, we discuss the experience we gain

from applying the framework as an interpretative

lens; does it make sense and does it provide new

insights to the misfit we found in our previous work.

We present challenges and insights as questions for

future debate.

In section 6, we conclude and answer our overall

questions. We conclude suggesting how our

experience with the framework may contribute to the

evolution and refinement of the interpretative lens

and hopefully inspirer to an interesting future

conversation in the area of ITKA’s.

3 CASE PRESENTATION &

UNDERSTANDING

The company has approximately 15.000 employees

of whom 1300 works at the head quarter in Denmark.

A consequence of the distributed workforce is that

people collaborate less collocated and often

distributed with project-teams all around the world.

They are very dependent on UC&C technology for

coordinating work, assisting each other, share

knowledge and information in a here-and now

manner.

Our presented understanding comes from the

interpretation from a facilitated discussion on

improving knowledge sharing practices with eight

participants from the organization that took place in

February 2015. We saw issues of people feeling

socially disconnected because of a situated practice

of “never putting on video in virtual meetings and

conference calls”…”I now feel a distance to my

The Misfits in Knowledge Work - Grasping the Essence with the Lens of the IT Knowledge Artefact

437

colleagues”(participant). The interrelatedness in

these quotes are better understood from the lens of

social presence theory. Social presence is the

acoustic, visual, and physical contact that can be

achieved between two [or more] communication

partners (Kaplan and Haenlein 2010). Social presence

involves intimacy and immediacy in the

communication. Following this logic, social presence

are lower for mediated (calls) and higher when

interpersonal (face-to-face); low for asynchronous (e-

mail) and higher for synchronous (live chat) (Kaplan

and Haenlein 2010). When feeling caught in e-mails

and calls without face expressed in “never putting on

video” the feeling of intimacy and immediacy should

be low. It seems that it affects knowledge sharing on

a somehow more profound level:”From previously

sharing a lot of day-to-day knowledge to now an

obsessive focus on text and documents”…”is

changing our knowledge sharing focus”.

The interrelatedness in these quotes are better

understood from the lens of Brown and Duguid

(2000) promoting how we generate knowledge in

practice, but implement it through process in

organizational contexts. Practice emphasizes the

lateral connections within an organization, the

implicit coordination and exploration that, for its part,

produces things to do. Process emphasizes the

hierarchical, explicit command-and-control side

of

organization - the structure that gets things

done. Practice without process tends to become

unmanageable; process without practice becomes

increasingly static (Brown and Duguid

2000). UC&C, as mentioned in the introduction, is an

ensemble of IT-artefacts, supporting interactions

between people coordinating and communicating

virtually. When emphasizing lateral connections and

the implicit coordination between team-members, it

becomes clearer that UC&C is a medium for practice

knowledge in an organization and as such supports,

the horizontal structure in the organization.

The appropriation of UC&C and the situated work

practices in this case, is “changing our knowledge

sharing focus” …”From previously sharing a lot of

day-to-day knowledge to now an obsessive focus on

text and documents”. They communicate work–

output and coordinate tasks in a more formal way,

using documents and e-mails. It seems that they use

UC&C for transfer of information and not for

promoting practice knowledge. In communities of

practice, ideas move with little explicit attention to

transfer and practice is coordinated without much

formal direction; they seem to acknowledge the lack

of practice knowledge as a problem and recognize it

as an important element of knowledge creation in an

organization.

The lack of social presence and lack of practice

knowledge seems to illuminate the cultural change

expressed “previously being socially oriented”. The

distribution of colleagues – co-located and distributed

- are tipping in the direction of distributed work. In

these setting UC&C should/could support the

informal connections and social interactions,

promoting the horizontal structure in the organization

but it seems that it falls short in providing this, due to

an emerged situated enacted practice on the

individual level, skewing the focus on practice

knowledge to a transfer of information. The perceived

related change of culture “changing our knowledge

sharing focus and company culture “seems essential

in understanding the situation.

Goffee and Jones (1996) promotes a view on how

people relate to a community, based on either

sociability or solidarity. Sociability is present when

we can see friendliness and non-instrumental

relations among members of a community. When we

see people share ideas, interests, values and attitudes

through face-to-face relations, sociability is build and

sustained. Solidarity is when people see each other as

instruments for achieving results, pursuing -

nevertheless - shared strategy goals quickly and

effectively. Building relations with colleagues comes

from common tasks, mutual interests and shared

goals (Goffee and Jones 1996). Organizations should

seek an equilibrium between the two (Goffee and

Jones 1996)

When colleagues primarily interacts with

colleagues located in other countries and regions, and

when the relation is not build or sustained with face-

work as in “never putting on video” the more

instrumental the relationships gets. In this case, it

affects all relationships “I now feel a distance to my

colleagues”. The social side of work decreases and

in-personal relationships arises and the possibilities

for creating knowledge trough the sharing of practices

declines.

Our understanding of the case comes from

illuminating certain aspects, abstracting it with theory

supporting our interpretations. In this case, we see the

situated enacted practice use of UC&C influences the

very type of knowledge shared and again influence

the community culture, which again influences how

much importance is put on social presence from the

daily appropriation of UC&C. The case reveals a

situation of socio-technical misfit. We see the

entanglement of people, technology and

organizational use (Orlikowski and Iacono 2001) not

amounting to joint optimization (Sarker et al. 2013).

KITA 2015 - 1st International Workshop on the design, development and use of Knowledge IT Artifacts in professional communities and

aggregations

438

4 APPLYING THE ITKA

FRAMEWORK

Tackling the situation from a socio-technical

perspective, we try to understand why the underlying

intention of fit and optimization between the technical

system and social system (Sarker et al. 2013) is not

achieved. In our former article (Harder Fischer &

Pries-Heje 2015), we conclude that users are in fact

appropriating this technology, by improvising (Sarker

et al. 2013) and adopting individually (McAfee 2006)

balancing individual autonomy with experienced

productivity in work. On the individual level, they –

in socio-technical terms - produce a fit, but on the

organizational level these appropriations does not

seem to amount to joint optimization.

It seems as if the situated appropriation of UC&C

creates a social void inhibiting the general ability to

share practice knowledge in the whole organization

and in the end – changing the community culture. We

seek a deeper understanding of the underlying nature

of UC&C grasping the essence of socio-technical

fits/misfits in interaction knowledge work.

In this section, we experiment with the

interpretive lens of ITKA’s from Cabitza and Locoro

(2014) applying it in the manner described in section

2, we answer the questions from table 1

consecutively.

Q1: Is UC&C an IT-artefact? Orlikowski and

Iacono (2001) provides five premises for IT-artefacts.

In their view IT-artefacts are not natural, neutral,

universal, or given; they are embedded in some time,

place, discourse, and community; they are made up of

a multiplicity of often fragile and fragmentary

components; they are neither fixed nor independent,

but emerge from ongoing social and economic

practices. They are not static or unchanging, but

dynamic. UC&C is clearly dynamic, the

appropriation emerges from ongoing social and

economic practices and is clearly embedded in a

community culture.

UC&C is not neutral or given. UC&C is promoted

in organizational settings as enabling easier

communication, faster and more efficient

collaboration from virtually anywhere, anytime (Silic

and Back 2013). Moreover, the intent is to deliver

flexibility, interoperability and efficiency (Silic and

Back 2013). Hence, UC&C is an IT-artefact.

Q2: Is it an IT Knowledge Artefact (ITKA)? We

adopt the view from Cabitza and Locoro (2014)

defining ITKA as “a material IT artefact which is […]

purposely used to enable and support knowledge

related processes with in a community” (Cabitza and

Locoro 2014). In our case, UC&C is used for

transferring knowledge. This makes UC&C an ITKA.

Underneath the value propositions of UC&C lies an

intent of establishing more appropriate knowledge

flows in dispersed organizational contexts. The

intention of UC&C is clearly to provide a digital

manifestation of the horizontal informal structure

supporting the flow of practices i.e. practice

knowledge in an organization. Either way, seen from

the perspective of Knowledge Artefacts (KA) - it

could be described as an “item that captures explicit

or [and] tacit knowledge” (Smith 2000, in Cabitza

and Locoro 2014). Applying a socio-technical

perspective on UC&C, it becomes clear that this IT

artifact enable and support knowledge-intensive

activities and tasks, hence being a IT-knowledge

artefact.

Q3: Is it socially situated or representational

ITKA? First, we must interpret the nature of

knowledge provided as either tacit, cultural, practical

and actionable or explicit and representational.

Representational ITKA’s provides structured sources

of static knowledge while socially situated ITKA’s

acts as a support or scaffold to the expression of

knowledgeable behaviors (Cabitza and Locoro 2014)

and practices. UC&C has the ability and

intentionality to be a scaffold for unfolding practical

wisdom (Nonaka and Takuechi 2011) throughout a

dispersed organization and as such is the opposite of

static knowledge. The ontology is clearly cultural,

practical and actionable. Second, we must interpret

the epistemology as being either constructivist,

interactionist and emergenist or positivist. UC&C is

clearly interactionist, providing interactions with an

underlying notion of interactions as sense-making.

We thus categorize UC&C as a socially situated IT

knowledge artefact.

Q4: Is UC&C an ITKA-based application? An IT

knowledge artifact is a class of software applications

that encompass material artifacts either designed or

purposely used to enable and support knowledge

related processes within a community (Cabitza and

Locoro 2014). UC&C is designed specifically to

enable and support the lateral connections and

implicit coordination in work, the backbone of

sharing practice knowledge. As such, it is an ITKA

based application. Adopting the view from Livari

(2007) on typologies and archetypes of IT-

applications, we can refine the answer by interpreting

UC&C primarily as a medium with the specific role

and function to mediate. Livari (2007) mentions e-

mails, instant messaging, chat rooms and blogs as

examples of mediators. In UC&C, a combination of

these applications are unified through an interface

with possibilities for talk, calls and video and

The Misfits in Knowledge Work - Grasping the Essence with the Lens of the IT Knowledge Artefact

439

presence indicators, extending the mediation of text

to also sound, picture and presence. The knowledge

mode is typically unstructured as in audio/calls and

free text. With the use of video, a tacit dimension

comes along. In the case, we see that this ensemble

of IT-artefacts also gives way for more structured

knowledge modes of transfer of explicit knowledge.

The focal point either way is enabling or support of

knowledge related processes we will categorize it as

an ITKA-based application.

Question 5: Can we classify the ITKA according

to the degree of objectivity and situativity, implied

from the design input and requirement for the IT

artifact as the final out-put.

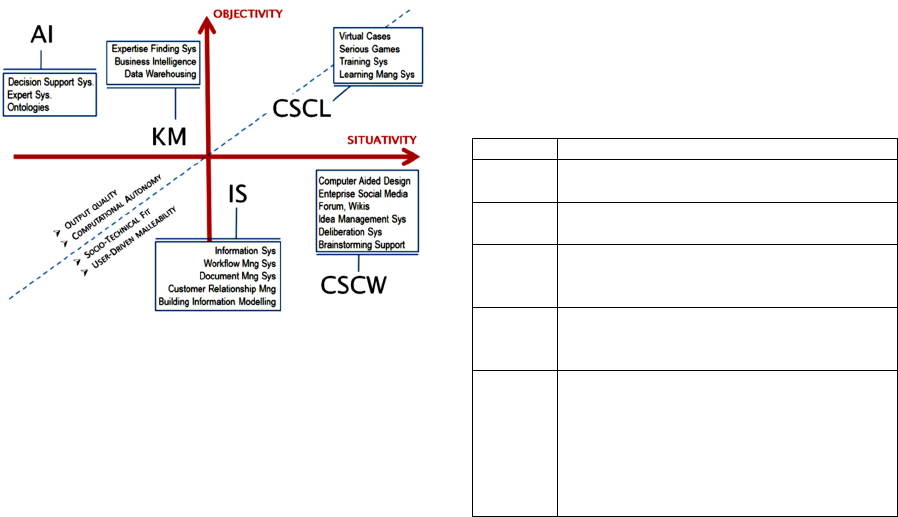

In figure 1, we see each group of ITKA-based

applications associated with a research stream, design

principles, values and assumptions of the disciplines

that lays at the intersection points in the figure

(Cabitza and Locoro 2014).

Figure 1: Classification of ITKA-based applications.

(Cabitza and Locoro 2014).

Having categorized UC&C as a socially situated

knowledge IT artefact and as a KITA-based

application, we must be able to express the degree of

objectivity and situativity implied by the design input

and requirement for the IT artifact as the final output.

Situativity, is the extent to which the KA is capable

to adapt itself to the context and situation at hand, as

well as the extent it can be appropriated by its users

and exploited in a given situation (Cabitza and

Locoro 2014). The situativity side of figure 1 is

clearly the appropriate hemisphere. The design

principles behind the UC&C is end-user malleability

and the values and beliefs of out-put is a socio-

technical fit. The objectivity hemisphere implies to

what extent the KITA can handle quantifiably

information in a centralized way and to which extent

it supports standard processes (objective knowledge)

with computational autonomy as design principle and

quality as the values and beliefs in out-put. The

degree of objectivity in the design of UC&C seems

nonexistent. UC&C as a design belongs to lowest

right side in figure 1. The specific appropriation in

our case shows an interesting dynamic. Caused by the

high degree of situativity, users change the purpose of

the design hence moving it towards more objectivity

decreasing the perceived socio-technical fit between

technology and system.

Seen from the design view it is possible to map

UC&C in the right lower corner in figure 1. When

appropriated in the specific context of the case, it

becomes uncertain to where it moves. From the case,

we witness a move towards more objectivity

interpreted as the need for documenting which

implies a preference for quality in out-put. We also

witness a deselection of video, implicating a move

away from practical knowledge created through

interactions. What is apparent from our case is that

this move negatively influences the creation of

knowledge through sharing practice and influences

community culture. We find that this move challenges

a meaningful classification.

Table 2: Summary of questions and answers.

Questions Answers

Q1

UC&C is an IT-artefact; dynamic, embedded

in context.

Q2

The intention is to support practice

knowledge creation and thus is an ITKA.

Q3

The ITKA is socially situated; an underlying

interactionist view on building culture from

practices.

Q4

UC&C is an ensemble of ITKA-based

applications supporting many practices of

knowledge sharing and creation

Q5

Seen from a design input view a high degree

of situativity and user-driven malleability is

evident. It should produce socio-technical fits

as output. The users appropriate UC&C with

intentions of transfer and produces misfits.

This dynamic makes is difficult to classify

meaningful in figure 1.

To make sense of classification, the categorization

tool should provide knowledge for designers and

analysts to understand better the design and the use

from the ontology and epistemology implied. With

the possibility of negative impacts from

sociotechnical misfits or decrease in quality output, it

is essential. It seems that the dynamics in use from

user appropriation is difficult to grasp in the present

framework.

The examples and the research streams of IS,

CSCL and CSCW should guide us then. We see some

KITA 2015 - 1st International Workshop on the design, development and use of Knowledge IT Artifacts in professional communities and

aggregations

440

important differences. Reflecting upon the research

streams and the associated applications, we sense an

underlying notion of planed change (Sarker et al.

2013). UC&C is rarely introduced as a planned

change (McAfee, 2006). UC&C is an ensemble of IT-

artefacts, which implies that certain practices with

artifacts could come into the foreground, we do not

detect the same degree of malleability in IS, CSCL

and CSCW. The software applications in the IS-box

does not seem to support the important horizontal

informal structures supporting the sharing and

creation of practice knowledge, created by people and

their interpersonal relations through daily situations

where social presence is important. We acknowledge

that software applications in the CSCW-box supports

informal interactions between people, but often in

specific project-work with a fixed and planed

purpose. In comparison, UC&C is supporting

companywide knowledge creation through the ability

to share practice knowledge. The software

applications in the CSCL-box has specific intentions

of organizational learning purposes. In other words,

we cannot assign UC&C to any of the research

streams.

Experimenting with the framework has been

valuable and has given us some new insights and

knowledge of the essence of misfits. We find it

difficult though to fit UC&C in the contemporary

research streams boxing in the software application.

We also find it difficult to fixate it in the figure 1.

In the following section, we will discuss what we

have gained from using the interpretative lens. We

end with some questions for the KITA community, to

progress in the enrichment and improvement of the

framework.

5 DISCUSSION

We have answered the questions out-lined in section

2, with our understanding from the case description in

section 3. In section 4 we used the interpretative lens

as a categorization tool, just as intended from the

authors ”A tool for analysts and designers to interpret

the peculiarities of the setting hosting ITKAs, as well

as to understand the ways and goals according to

which ITKAs are built and used” (Cabitza and Locoro

2014). We will discuss what we gained by answering

the questions, interpreting the specific use of UC&C

in a case of socio-technical misfit.

In general, by applying the ITKA-interpretative

lens, the embeddedness of technology in a complex

and dynamic social context becomes clear. ITKAs are

neither dependent nor an independent variable but

instead enmeshed with the conditions of its use

(Orlikowski and Iacono, 2001) and within its culture.

Framing UC&C as an IT-artefact makes sense

seeing more clearly the changeable and dynamic

nature of the UC&C.

It makes sense to view UC&C as an IT-knowledge

artefact, since it brings the important element of

knowledge creation through sharing of practice

knowledge to the foreground.

Categorizing UC&C in the light of ontology and

epistemology makes sense, understanding the

intentions underlying this ITKA. Defining it as a

socially situated ITKA is valuable too, since it brings

forward the tension between design-intent and user-

appropriation. From our case, we see a clear

dependency between the specific appropriation of

using UC&C and the transfer of information

happening. UC&C in this case, is no mediator of

human-to-human interactions increasing social

presence. Thus stated as an important foundation for

sociability and producing practical knowledge. The

use then is different from the design-intention.

Framing UC&C as a specific ITKA-based

application – a medium - draws attention to the

intention of design and use of the applications. Being

an ensemble of IT-artefacts, the knowledge forms

vary from formal to informal. It highlights the issues

and tensions present in the case. The expressed

frustration of a socio-technical misfit from an

organizational point of view, while at the same time,

choosing preferred knowledge modes. These

dynamics creates an unintended move.

We find it important to understand the nature of

implementation with UC&C. Introducing UC&C in

organizations is not a planned change. Instead, the

adoption is voluntary and random. Andrew McAfee

(2009) promotes the view that adoption - as in joint

optimization - within this archetype of IT-

applications is the sum of a large number of

individual choices about which technologies to use

for communication, collaboration and interaction

(McAfee, 2009).

In our prior article (Harder Fischer & Pries-Heje

2015) we saw the paradox of individual knowledge

workers producing autonomy in knowledge work

settings with UC&C by adopting practices for

becoming more productive on the individual level yet

becoming less productive on a collective level.

The ITKA-interpretative lens provides insights

and reveals a more fundamental tension between the

individual knowledge worker and the organizational

setting in which the technologies are appropriated.

Focus on knowledge, the center of knowledge

work is a valuable contribution to the evaluating

The Misfits in Knowledge Work - Grasping the Essence with the Lens of the IT Knowledge Artefact

441

UC&C. We have become more aware of the actual

meaning that people - appropriating these artefacts -

assign to them.

With underlying assumptions about socio-

technical fits, it also makes the misfits clearer.

Reflecting on situativity and objectivity highlights the

relatedness between knowledge, practices with

technology and intentions with the software

applications, in a specific culture and context.

So why do we have difficulties when classifying

the KITA-based application and draw a box in figure

1? While we certainly belong to the situativity

domain, with aspects of extreme end-user

malleability and fit (possibility for misfits) as

dominant dynamics, it is still difficult to position it

meaningfully. Popular speaking it is a moving target.

We are missing a dynamic dimension of use truly

seeing the impacts from individual or collective

appropriations and practice-uses in the situated

context. The associated applications within the

research streams are designed according to intentions

of objectivity and situativity. There seem to be an

underlying notion of a logic relationship between

design in-put and use out-put. From our case, we

report on a change of purpose, from people’s practice-

use, with the ITKA-based application. These

dynamics are the core of situativity. Reflecting on the

ITKA-based applications (gathered under research

streams), we see a common denominator though; that

all of these systems and applications are designed and

formally implemented in an organizational context,

hence grounded on believe that a fit between intended

design purpose and end-user malleability can be

planned and managed.

As such, the framework seems to emerge from

established research domains, build from a common

mindset of planned change, steered design and

mandated IS-implementations. We seem to lack the

ability to categorize and classify an end-user

malleable KITA, introduced at random, adopted on

the individual level, so moldable and powerful, in a

specific time, context and culture that it can change

the design intention of the software.

We see some issues that we find important to

discuss further in the process of refining the

framework in the shared pursuit of providing a

valuable tool for designers and analysts to understand

design requirements but especially the use of ITKAs

in peculiar settings in the future.

We ask the following questions. The questions are

our primary contribution in this paper. The questions

comes from our experiences from experimenting with

the lens from the framework:

Table 3: Questions for the KITA-community.

Questions How do we tackle:

1 Dynamic ITKAs from a sociotechnical pers-

pective underlying the interpretative lens?

2 ITKAs influenced by user appropriation,

changing the setting of knowledge focus and

community culture?

3 The distinction between intentions in design

and intentions in use?

4 The difference between planned change and

individual driven appropriation of ITKA’s?

5 The distinction between ensembles of ITKAs

as opposed to single ITKA’s?

6 How do we classify and understand moving

ITKA-ensembles.

7 The issue of our difficulties of not being able

to assign UC&C to a research stream?

8 ITKAs that support both tacit/explicit- and

process/practice knowledge?

9 A lens viewing the organizational and the

individual level at the same time?

The changes in the workplace, happening right

now, seems to be running a little ahead of IS-research.

In future knowledge work, individuals and their

interactions - and not the hierarchy - becomes the

locus of value-creation. Connecting, interacting and

producing knowledge of high quality

productively/efficiently becomes increasingly

important. Knowledge professionals, freelancers and

contractors will increasingly configure and co-

configure the many ITKAs in order to create value

and at the same time be productive. They might even

bring with them individualized ITKA software

applications and preferences for productive practices.

Supporting and sustaining the equilibrium of

process & practice and sociability & solidarity will be

the foundation for successful and productive value-

creation in networks and communities.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this section, we conclude by answering our overall

questions: What do we gain from evaluating UC&C

as an ITKA in the peculiar setting? Can we use the

framework to understand the design and use of this

ITKA in other settings? Can our experiences with the

framework reveal new insights that can enrich the

interpretative lens?

The very aim is to take the socio-technical nature

of UC&C more serious, to be able to minimize the

negative consequences of technology in

organizations (Harrison, 2007). Seeing UC&C in the

light of the ITKA framework was valuable. It gives

KITA 2015 - 1st International Workshop on the design, development and use of Knowledge IT Artifacts in professional communities and

aggregations

442

us a better understanding of the difficulties of joint

optimization with the individually driven

appropriation of dynamic knowledge IT-artefacts in

different contexts, with different purposes for

supporting knowledge creation.

We support the purpose of the work (Cabitza &

Locoro 2014) seeking an interpretative lens that

illuminates the dynamic relatedness between people,

knowledge and IT-artefacts and the community

culture (evident in this case). It seems that the

framework becomes a little backward looking more

than forward-looking. We discuss how we

meaningfully can classify the individual-driven

appropriation of dynamic knowledge IT-artefacts in

different settings with situated preferences for

knowledge sharing and creation. These dynamic

forces are important to conceptualize in the

framework. We believe that the nature of KITAs with

powers to change knowledge sharing focus and

community culture is important to understand in the

future value-creation process.

We believe that our experimentation with the

ITKA interpretative lens and the resulting questions

for the KITA-community, will contribute to the work

and improvement of the ITKA-framework. We find it

important and valuable to supporting the

development of a lens, used by for designers and

analysts, so that design and appropriation of KITAs

in the future workplace can contribute to positive

impacts. Grasping the essence of misfits in

contemporary knowledge work, would be a valuable

starting point.

REFERENCES

Brown, JS. & Duguid, P. (2000) “Practice vs. Process: The

Tension That Won’t Go Away” Knowledge Directions.

Spring 2000.

Cabitza, F. & Locoro, A. (2014). Made with Knowledge:

disentangling the IT Knowledge Artifact by a

qualitative literature review. In KMIS 2014:

Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on

Knowledge Management and Information Sharing,

Rome, Italy, 21-24 October 2014 (pp. 64–75).

Goffee, R. & Jones, G (1996) “What holds the modern

company together” Change Management, Harvard

Business review, November-December issue 1996.

Harder-Fischer & L, Pries-Heje, L (2015) “Co

configuration in Interaction work”, IRIS Conference,

Oulu, Finland 2015. Proceedings handed out on sticks.

Paper 37. www.iris2015.org.

Harrison, M. I. et al. (2007). Unintended consequences of

information technologies in health care—an interactive

sociotechnical analysis. JAMIA, 14(5), 542-549.

Kaplan, A.M. & Haenlein, A.M. (2010) “Users of the

world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of

Social Media”. Business Horizons (2010) 53, 59—68,

Livari, J. (2007). A paradigmatic analysis of information

systems as a design science. Scandinavian Journal of

Information Systems, 19(2), 39-64.

McAfee, A, “Mastering the three worlds of information

technology”. (2006) Harvard Business Review,

November issue 2006. 141 – 148.

McAfee, A. “Enterprise 2.0 – collaborative tools form your

organizations toughest challenge” (2009), HBR Press.

Nonaka, I. & Takeuchi, H. (2011) “The Wise Leader”,

Harvard Business Review, May issue 2011. pp 1-13.

Sarker, S. Chatterjee, S. Xiao, X. (2013) “How socio-

technical is our research? An assessment and possible

way forward”. Proceedings of Thirty-Fourth

International Conference on Information Systems,

Milan 2013.

Silic, M. & Back, A. (2013) “Organizational Culture Impact

on Acceptance and Use of Unified Communications &

Collaboration Technology in Organizations”.

Proceedings of BLED 2013.

Orlikowski, WJ. & Iacono, CS. (2001) “Research

Commentary: desperately seeking the IT in IT-research

– A call to Theorizing the IT artefacts Information

Systems Research. 12(2), 121-134.

The Misfits in Knowledge Work - Grasping the Essence with the Lens of the IT Knowledge Artefact

443