Experiences of Tool-Based Enterprise Modelling as Part of

Architectural Change Management

Cameron Spence

Capgemini, Woking, United Kingdom

cameron.spence@capgemini.com

c.d.spence@pgr.reading.ac.uk

Vaughan Michell

University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading, United Kingdom

vaughan.michell@reading.ac.uk

Keywords: Enterprise modelling, business modelling, enterprise architecture.

Abstract: Enterprise Architecture is widely practised as a part of a strategic business change methodology and is often

vital to successful business change. This paper examines the pragmatic use of enterprise architecture

modelling (EAM) tools. A pilot survey of EAM practitioners identified that many companies abandon the use

of EAM tools despite the benefits that should result from their use. Some of the reasons for lack of

sustainability include (a) failures in modelling governance, (b) lack of alignment with the change method, (c)

users withholding information and (d) poor perception of EA itself.

1 INTRODUCTION

Enterprise architecture is a growing field that enables

the major aspects of business and IT activity to be

modelled and plans made for their change

(Hoogervorst, 2004). The use and application of an

integrated model of the business is key to supporting

change decision-making. However, a survey of the

current literature identified firstly that EA modelling

is often abandoned (e.g. (Meertens et al., 2011b));

secondly that business models vary greatly and do

not have a clearly agreed definition (Vermolen,

2010)); and thirdly there is a gap in the existing

literature regarding how enterprise architecture

modelling (EAM) can be made sustainable and

effective in its use as part of a principle change

methodology.

This paper first summarises some relevant

terminology related to the modelling of Enterprise

Architecture. We then present results from a pilot

survey of practitioners of enterprise architecture

modelling (EAM) based around the issues identified

from the literature. We then consider a number of

issues identified by the respondents in the execution

of tool-based EAM as motivation for further study.

2 THE PRACTICE OF

TOOL-BASED ENTERPRISE

MODELLING AS PART OF

CHANGE MANAGEMENT

Enterprise Architecture Modelling (EAM) is carried

out in both end-user and consulting organisations

(Hall and Harmon, 2005, Ganesan, 2008). This

section briefly explains and grounds some terms

related to tool-based EAM.

2.1 Enterprise Architecture

Rood (Rood, 1994) suggests an Enterprise

Architecture comprises: people, information and

technology. TOGAF (The Open Group, 2011) divides

the Enterprise into four domains: Business, Data,

Applications and Technology. Capgemini’s IAF

(Wout et al., 2010) uses four similar domains to

255

Spence C. and Michell V.

Experiences of Tool-Based Enterprise Modelling as Part of Architectural Change Management.

DOI: 10.5220/0005887902550260

In Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design (BMSD 2015), pages 255-260

ISBN: 978-989-758-111-3

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

TOGAF, but worded slightly differently. All broadly

recognise the need to cover business, information and

technology.

2.2 EA Frameworks

These provide a standard structure, vocabulary and

(sometimes) a process for carrying out EA work.

Examples of EA frameworks include TOGAF (The

Open Group, 2011)), DODAF (DoD, 2010)) and

Zachman’s Enterprise Architecture Framework

(ZEAF) (Zachman, 1987)). There are also reference

frameworks that help position and compare the EA

frameworks: the Generic Enterprise Reference

Architecture and Method (GERAM) (Bernus and

Nemes, 1996) which packages these within

Ontological Theories; and the newer EAF2 (Franke et

al., 2009).

2.3 Enterprise Architecture Model

An Enterprise Architecture Model is a miniaturisation

or representation of the components making up an

enterprise. These models might take a number of

forms, but are likely to consist (in terms of content)

mainly of representations of the entities, attributes

and relationships relevant to a particular viewpoint or

perspective. These may for example support decision

making (e.g. “show me a view of all business services

that are reliant upon obsolete infrastructure”, as

described in (Spence and Michell, 2011). This is

helpful in governing the evolution of the enterprise IT

portfolio, as discussed later.

2.4 Enterprise Architecture Modelling

EAM is the activity of producing and maintaining EA

Models. The content of the models may well be

created by multiple agents, and also viewed by

multiple agents for a variety of reasons. These agents

will need views tailored to meet their specific needs,

showing different entity subsets, attributes and

relationships. The selection and creation of these

views and the entities and attributes in them, may or

may not be specified by a particular architecture

framework in use, but will typically need adapting to

the specific context needed for modelling. This drives

the need for EAM tool to be customisable.

2.5 Enterprise Architecture Tools

An EA Tool is an instrument used for EA Modelling.

Whilst EA Models can use pen and paper, or simple

drawing tools (e.g. Microsoft Visio®), it is much

more efficient using a software tool designed

specifically to do the job (Hall and Harmon, 2005).

TOGAF 9.1 (The Open Group, 2011) refers to EA

tools, (in chapter 42) as “automated tools”. This paper

focuses on tool-based EAM, as distinct from non-

tool-based EAM.

Commercial research organisations (Brand, 2014,

Peyret et al., 2011, Hilwa and Hendrick, 2012) divide

“modelling and architecture tools” into the following

categories:

• Object Modelling tools

• Business Process Modelling Tools

• Enterprise Architecture Tools

• Data Modelling Tools

EA Tools are, in terms of revenue, the fastest

growing in this particular market segment [21]. When

combined with a large failure rate (our survey

indicated perhaps an 85% failure rate, if failure is

defined as the modelling having ceased) from

modelling efforts, we can see that aside from failure

to gain the required benefits, the amount of spend on

EAM tools that ends up being wasted might be in the

region of $230M in 2016 (if the percentage failure

rate in our qualitative survey were to be

representative of general EAM activities).

3 TOOL-BASED ENTERPRISE

ARCHITECTURE MODELLING

EXPERIENCES

To explore whether the EAM issues identified earlier

in the literature (such as (Meertens et al., 2011b),

discussed later) occur in practice, we carried out

qualitative research. We interviewed seven

consulting Enterprise Architects who responded to an

email invitation sent to approximately 400 staff

within an IT services company, seeking volunteers to

be interviewed that had prior experience with tool-

based EAM. This is not as small as percentage as it

may appear, given that the majority of the staff will

have had no experience with EA modelling tools,

which are not used as standard within this company;

and so the pool of qualified subjects available at this

stage was relatively small.

A set of structured/ telephone interviews was

carried out on the respondents. As our future research

direction is focused on the value of the tool-based

EAM, and the factors affecting its sustainability, we

gathered information about the value (expected and

Fifth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

256

perceived) of the EAM effort and what lessons were

learned. Some questions also related to possible

activities that might lead to it being more sustainable.

The key questions were:

• Who was the client, in what industry sector?

• What EA tool was used?

• How was the tool used (e.g. single/multiple

users, one-off or part of lifecycle process, were

multiple users able to do updates in parallel)?

• What support was given (training, coaching,

documentation)?

• What was the scope of the modelling (business,

information, technology)?

• Who was responsible for introducing the tool

(client or supplier)?

• Who paid for the tool?

• What value did the client, and the supplier,

expect to get from it?

• How was that, or how could that been, measured?

• What value did the client, and the supplier,

actually get from the tool?

• What processes were in place to support and

govern the use of the tool?

• What were the factors in the modelling

environment (people, process or technology) that

helped the EAM activity? What factors hindered

it?

• Are there any features of the tool that would help,

or hinder, its sustained use over the longer term?

• Is the client still using the EA tool? If not, why

not?

• In hindsight, what do you wish you had known

before you started using the tool, and what would

you change if you did it again?

A summary of the key results is offered below.

These reflect a subset of the answers to the questions

posed:

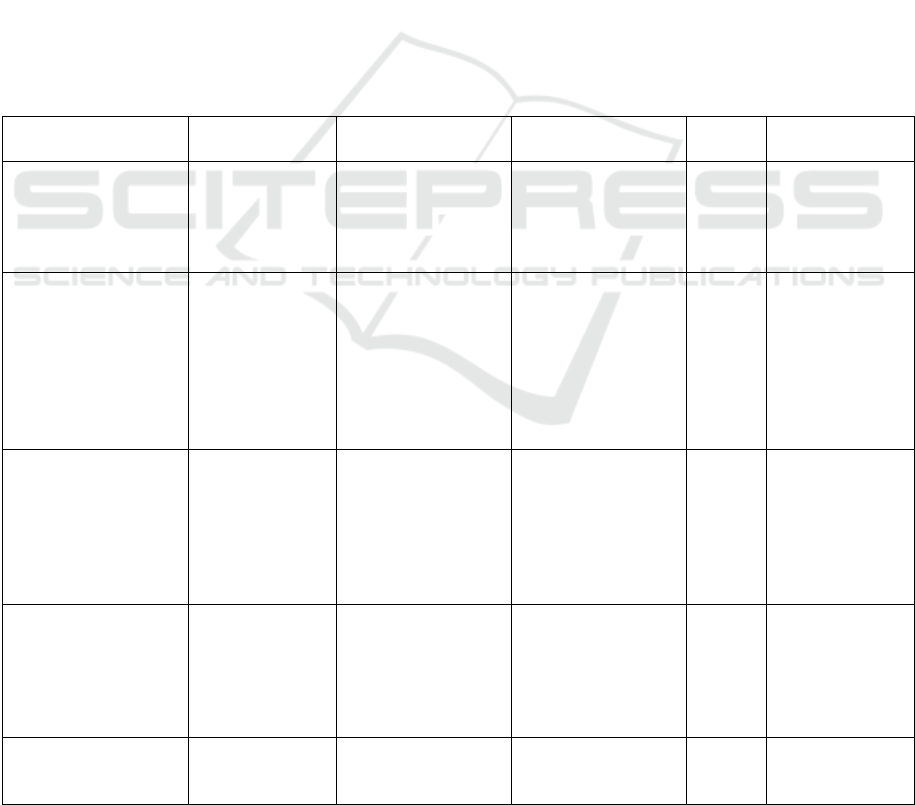

Table 1: Summary of Some EA Modelling Experiences.

Expected value Actual value What helpe

d

What hindere

d

Still in

use?

Abandoned

b

ecause

Quicker project

lifecycle reducing

costs and risks due

to less ambiguity

Projects were

no faster as

decisions

delayed

anywa

y

Training;

top-down initiative

Cultural and

political issues; the

need to win people

over

?

N

o specific

expectations

Single version

of truth;

enabled

persuasion and

challenge;

detect errors,

saved wasted

effort and time

Many ways of

creating a model;

not one fixed

standard

N

ot enough

p

eople

had access to tool;

cultural resistance

Barely Seen as

opposed to

Agile (“high

ceremony”)

Supplier made it

prerequisite for

replatforming IT

estate

Saved a month

by skipping

due diligence

as information

was already

captured

Librarian role;

buy-in from

business;

publishing results;

lessons learnt;

people signing off

on conten

t

Tool struggling to

produce suitable

diagrams; scope

unclear at start;

people holding

onto ‘their’

information

N

o Replatforming

finished; client

believed they

no longer

needed the

information

Looking to save

money, so required

to understand the IT

estate and therefore

support

rationalisation

Unsure but

client architects

seemed pleased

Having a librarian

for the tool;

having clear scope

for modelling

Tool not easy to

use; lack of

training

Yes

Traceability

–

impact of change –

how strate

gy

is

Understood

impact of

chan

g

e

Tool supplier staff

very helpful; easy

to use;

Tool reports

sometimes hard to

read; some tool

N

o Unknown

Experiences of Tool-Based Enterprise Modelling as Part of Architectural Change Management

257

worked out in IT

p

ro

j

ects

features non-

intuitive

Understand IT

estate as

prerequisite for

application

rationalisation and

modernisation

Complete

picture of their

estate to enable

application

rationalisation

Having core

modelling team to

help others;

quality control

Lack of

governance;

reporting hard to

configure

N

o Tool issue

(reporting) and

process issue

(not following

proper

p

rocesses)

Understand IT

estate as

prerequisite for

application

rationalisation

Ability to

perform

complex

analysis,

communicate

b

usiness value

Repository

management

features, ease of

customisation

Tool quirks; high

cost of tool

N

o Client felt tool

was too

expensive

This pilot survey clearly suggests there is an issue

sustaining the use of EA tools; it confirms that the

majority abandoned the use of EAM (see “Still in

use” column in table). This prompts the research

question: why? - In only one of the 7 case studies has

the end-user organisation continued to carry out the

modelling activity, in some cases despite the benefits

that were being obtained.

The failure to produce benefits has been traced in

some cases to issues with the way it was being used

(e.g. “our main issue was caused by people not

following process / guidelines, and not updating

repository as designs were changed”).

In some cases the issue was with the tool itself

(e.g. “the client realised that the repository couldn’t

actually be generated from the tool, they believed it

couldn’t deliver the expected value: format wasn’t

good”).

4 DISCUSSION OF SURVEY

RESULTS VS RELEVANT

LITERATURE

This section sets the results in the context of the

current literature.

A systematic review of business modelling carried

out in 2010 (Vermolen, 2010), relating to the

Business layer of Enterprise Architecture concluded

that literature related to business modelling had a gap

in terms of the use of theory; and that there appears to

be a lack of papers in the leading IS journals on the

topic of business models.

Meertens et al. (Meertens et al., 2011a)

recognises that many projects involving business

modelling (a subset of EA modelling) end after an

initial phase and do not deliver the expected benefits;

this mirrors our experience from the limited case

studies above.

The topic of business modelling is the subject of

much existing research, including a proposed

research framework published in 2004 (Pateli and

Giaglis, 2004), which organises business model

research into a number of categories including

“Design Methods and Tools” and “Adoption factors”,

both of which seem initially to be relevant to the topic

at hand (sustainability of EA modelling). Some

primary and secondary sources are organised

according to these categories. In the Design Methods

and Tools category, papers describing two specific

modelling languages (UML (Eriksson and Penker,

2000) and eBML (Lagha et al., 2001)) are listed, but

nothing that addresses the specific question of the

value of Enterprise Architecture modelling using

tools such as discussed above.

The motivations for EAM are to allow the

visualisation and reporting on aspects of the

Enterprise Architecture (part of the governance

referred to below), and to provide an environment

where the structure of the Enterprise can, in a

simulated fashion, be altered in some way to examine

the consequences of the alternation. There may be

specific business scenarios that lend themselves to

this kind of activity, for application rationalisation

(one of the scenarios encountered in the survey), or

mergers and acquisitions (Freitag and Schulz, 2012).

Some of the tasks mentioned in this paper are related

to expected business benefits, for example carrying

out due diligence (to reduce risk and cost through

better knowledge). However, the study does

recognise that the literature does not confirm (or

disconfirm) that using this kind of EA management

technique (including modelling) improves the

success rate of mergers and acquisitions.

The literature surveyed so far focuses mainly on

discrete elements (for example, specific methods or

Fifth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

258

languages), rather than the activity of EAM that

draws them together for a particular benefit. The

value of business process modelling in particular is

discussed by Indulska (Indulska et al., 2009) where

three particular areas of concern are raised; two of

these have potential relevance in areas wider than just

business processes (standardisation of modelling

approaches and the identification of the value

proposition of the modelling). Standardisation of the

modelling language is covered by Lankhorst

(Lankhorst, 2013), as is the use of a particular

modelling tool.

The value of the modelling seems to be assumed

by Jonkers (Jonkers et al., 2004) to relate to

“informed governance” and references (Op't Land et

al., 2008) that discusses the value of EA in terms of

the governance of an enterprise and its

transformation. The relationship between the

acquisition and use of a tool and a major

transformation initiative is illustrated in one of the

cases surveyed, where a supplier insisted that the

modelling had to be done as a prerequisite for a

replatforming effort. The survey suggested that some,

but not all, modelling was done explicitly in order to

help a particular transformation exercise; and that

having a clear reason for the tool is no guarantee that

its use will be sustained over time.

Given the link between EA and IT governance,

this suggests that one line of reasoning that may bear

further research, related to IT governance and tool-

based EAM, might be:

(1) Effective IT governance requires EA

(2) Effective (accurate and comprehensive)

management of EA information requires an EA

tool

(3) Effective IT governance requires an EA tool

(from (1) and (2))

Echoing a comment from one of the pieces

surveyed, there is a need to do further research in a

number of related areas:

• What is the value that we can actually expect to

get from this activity (tool-based EAM), and in

particular can the argument related to IT

governance be more clearly clarified and

investigated?

• What needs to be done in order to make this

sustainable rather than a short-term activity?

5 CONCLUSIONS

We have identified that although widely used as a part

of change management, EAM is often abandoned and

that there is a lack of formal definition and

understanding of the benefits of these models. We

have shown in a pilot survey in section 3 that there

may be an issue in practice with the sustainability of

attempts to execute EAM; these include:

• Issues with the tool itself

• Poor governance of the modelling

• Perception of EAM and EA being unnecessary

• Lack of ability to tailor the tool

• Need for cultural change

• People not wanting to share their information

• Modelling scope is not always clear

• Need to maintain quality in modelling

We have also identified in section 4 a gap in the

literature related to tool-base EA modelling as a

discipline. There is little work done on tool-based

EAM, and in particular in the business domain, a lack

of common understanding about what business

models should comprise. There is a recognition that

business modelling efforts often fail, with little

analysis of why this is so, and what should be done to

improve the situation. We have also identified a

possible direction for future research, related to the

value that tool-based EAM adds to Enterprise

Architecture and hence to IT governance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank a number of employees of

Capgemini who have provided information about

their professional experiences with EA modelling

tools: Steve Bramwell, Vincent Owens, Stephen

Timbers, Ian Mackie, Rebecca Paul and Andrew

Lazarou. Thanks also are due to Al Hilwa of IDC for

information on the market for EA modelling tools.

REFERENCES

Bernus, P. & Nemes, L. 1996. A framework to define a

generic enterprise reference architecture and

methodology. Computer Integrated

Manufacturing Systems, 9, 179-191.

Brand, S. 2014. Magic Quadrant for Enterprise Architecture

Tools. Gartner.

Experiences of Tool-Based Enterprise Modelling as Part of Architectural Change Management

259

DoD, D. 2010. Department of Defense Architecture

Framework (DoDAF) Version 2.02. In: Officer,

D. D. C. I. (ed.). U.S. Department of Defense.

Eriksson, H.-E. & Penker, M. 2000. Business Modeling

with UML: Business Patterns at Work, John

Wiley & Sons.

Franke, U., Hook, D., Konig, J., Lagerstrom, R., Narman,

P., Ullberg, J., Gustafsson, P. & Ekstedt, M.

EAF2- A Framework for Categorizing Enterprise

Architecture Frameworks. Software

Engineering, Artificial Intelligences, Networking

and Parallel/Distributed Computing, 2009. SNPD

'09. 10th ACIS International Conference on, 27-

29 May 2009 2009. 327-332.

Freitag, A. & Schulz, C. 2012. Investigating on the role of

EA management in Mergers & Acquisitions.

BMSD2012. Geneva.

Ganesan, E. 2008. Building Blocks for Enterprise Business

Architecture. SETLabs briefings.

Hall, C. & Harmon, P. 2005. The 2005 enterprise

architecture, process modeling & simulation

tools report. Business Process Trends, 1-206.

Hilwa, A. & Hendrick, S. D. 2012. Market Analysis:

Worldwide Modeling and Architecture Tools

2012–2016 Forecast and 2011 Vendor Shares.

IDC.

Hoogervorst, J. 2004. Enterprise Architecture: Enabling

Integration, Agility and Change. International

Journal of Cooperative Information Systems, 13,

213-233.

Indulska, M., Recker, J., Rosemann, M. & Green, P. 2009.

Business Process Modeling: Current Issues and

Future Challenges. In: van Eck, P., Gordijn, J. &

Wieringa, R. (eds.) Advanced Information

Systems Engineering. Springer Berlin

Heidelberg.

Jonkers, H., Lankhorst, M., Buuren, R. v.,

Hoppenbrouwers, S., Bonsangue, M. & Torre, L.

v. d. 2004. Concepts for modeling enterprise

architectures. International Journal of

Cooperative Information Systems, 13, 257-287.

Lagha, S. B., Osterwalder, A. & Pigneur, Y. Modeling e-

Business with eBML. 5th Int'l Workshop on the

Management of Firms' Networks (CIMRE'01),

Mahdia, Tunisia, 2001. Citeseer.

Lankhorst, M. 2013. Enterprise Architecture at Work:

Modelling, Communication and Analysis (The

Enterprise Engineering Series). Springer.

Meertens, L., Iacob, M. & Nieuwenhuis, L. 2011a.

Developing the business modelling method.

Meertens, L. O., Iacob, M. E. & Nieuwenhuis, L. J. M.

2011b. Developing the business modelling

method. In: Shishkov, B. (ed.) First International

Symposium on Business Modeling and Software

Design, BMSD 2011. Sofia, Bulgaria: SciTePress

- Science and Technology Publications.

Op't Land, M., Proper, E., Waage, M., Cloo, J. & Steghuis,

C. 2008. Enterprise architecture: creating value

by informed governance, Springer Science &

Business Media.

Pateli, A. G. & Giaglis, G. M. 2004. A research framework

for analysing eBusiness models. Eur J Inf Syst,

13, 302-314.

Peyret, H., DeGennaro, T., Cullen, A. & Cahill, M. 2011.

The Forrester Wave: Enterprise Architecture

Management Suites, Q2 2011. Forrester.

Rood, M. A. Enterprise architecture: definition, content,

and utility. Enabling Technologies:

Infrastructure for Collaborative Enterprises,

1994. Proceedings., Third Workshop on, 17-19

Apr 1994 1994. 106-111.

Spence, C. & Michell, V. Assessing the Business Risk of

Technology Obsolescence through Enterprise

Modelling. In: Shishkov, B., ed. Symposium on

Business Modeling and Software Design, 2011

Sofia. SciTePress.

The Open Group 2011. The Open Group Architectural

Framework (TOGAF) 9.1.

Vermolen, R. Reflecting on IS Business Model Research:

Current Gaps and Future Directions. Proceedings

of the 13th Twente Student Conference on IT,

University of Twente, Enschede, Netherlands,

2010.

Wout, J. v. t., Waage, M., Hartman, H., Stahlecker, M. &

Hofman, A. 2010. The Integrated Architecture

Framework Explained, Berlin Heidelberg,

Springer-Verlag.

Zachman, J. A. 1987. A framework for information systems

architecture. IBM Systems Journal, 26, 276-292.

Fifth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

260