Reminiscence of People with Dementia Mediated by a Tangible

Multimedia Book

Alina Huldtgren

1,3

, Fabian Mertl

1

, Anja Vormann

2

and Christian Geiger

1

1

Department of Media, University of Applied Sciences Düsseldorf, Josef-Gockeln-Str. 9, Düsseldorf, Germany

2

Department of Design, University of Applied Sciences Düsseldorf, Josef-Gockeln-Str. 9, Düsseldorf, Germany

3

School of Innovation Sciences, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

Keywords: Reminiscence Therapy, Dementia, Tangible User Interfaces.

Abstract: With the growing senior population the number of people with dementia is rising rapidly. Besides –

currently limited– pharmaceutical treatments, psychosocial interventions play a major role in ensuring the

life quality for people with dementia. Among these is reminiscence therapy, which helps people to

remember episodes of their past life and maintain their identity, while the disease progresses. The research

presented in this paper explores the role of a tangible multimedia artifact to support reminiscence sessions.

We describe the development of an interactive book that was tested in a care home with people with

dementia and caregivers. We present findings on the interaction with the book, its potential to mediate

reminiscence and communication, and on the perspective of caregivers using the book in the sessions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Due to the demographic changes and associated

population aging, the number of people suffering

from dementia is rapidly increasing

(Alzheimers.Net). Dementia is a condition commonly

associated with memory decline, however, the disease

also impacts other cognitive functions such as speech,

decision making, reasoning, or learning, thereby

making it more and more difficult for people with

dementia to engage in meaningful and social

activities. This in turn impacts their self-confidence

and quality of life (Wood et al., 2009).

Caregivers, on the other hand, often suffer from

stress and frustration, when caring for people with

dementia. Especially in more advanced stages of the

disease challenging behaviors such as apathy or

aggression impact the social interaction (Van der

Linde et al., 2012) and stimulating a conversation can

be very difficult. Until now pharmaceutical

interventions are rather limited. “Currently, five drugs

have been approved by the FDA for use in AD […].

These five drugs are supportive or palliative rather

than curative or disease-modifying therapies, and

they do not appear to alter the final outcome of the

disease.”(Casey et al., 2010) Therefore, psychosocial

interventions have gained in importance over the last

years. These include, e.g., memory training, reality

orientation and reminiscence therapy. Especially the

latter is considered a promising intervention for

people with dementia to improve mood, cognition,

and behavior (Woods et al., 1992). Furthermore,

reminiscence can increase interpersonal

communication (Kasl-Godley et al., 2000).

In our work we were interested in which way

advanced user interfaces and media technologies

could play a supporting role. We hypothesized that

the new opportunities that come with embedding

sensors and microcontrollers into everyday artifacts,

allow for the design of tangible interfaces in

combination with multimedia to be used by people

with dementia with little technological skills and

caregivers to stimulate reminiscence and

communication. In particular, haptics, images, audio,

and possibly other modalities like smell seem to offer

ways to stimulate affective memories.

In our research program, researchers and

designers from four disciplines (Media Technologies,

Design, Electrical Engineering and Social Sciences)

collaborate on socio-technical solutions for people

with dementia. Our research aims at empowering

people with dementia, on the one hand, through

active integration in the design processes of new care

technologies, and, on the other, by designing

solutions adapted to their needs and abilities. In the

following, we describe our work following a

research-through-design approach. In particular, we

Huldtgren, A., Mertl, F., Vormann, A. and Geiger, C.

Reminiscence of People with Dementia Mediated by a Tangible Multimedia Book.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2016), pages 191-201

ISBN: 978-989-758-180-9

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

191

describe the design of an interactive book that was

used in several field studies with people with

dementia of different degrees and their caregivers.

We provide insights derived from a field study into

how tangible user interfaces can support reminiscence

and communication between a caregiver and a person

with dementia and considerations to be taken into

account.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Reminscence Therapy

Researchers investigating dementia, especially those

following a person-centered perspective (Kitwood &

Bredin, 1992), believe that “the symptoms [e.g.

depression and fears] and behaviours [e.g. unrest,

aggression, wandering] of demented individuals are

not solely a manifestation of the underlying disease

process, but also reflect the social and environmental

context, as well as the demented individual’s

perceptions and reactions. Psychosocial interventions

can address these factors.” (Kasl-Godley et al., 2000).

Psychosocial interventions are even more important

in light of the limited success of pharmaceutical

interventions for dementia. Kasl-Godley and Gatz

reviewed the six main psychosocial interventions for

people with dementia: psychodynamic approaches,

reminiscence and life review therapy, support groups,

reality orientation, memory training and

cognitive/behavioral approaches. Each intervention

targets particular factors and addresses different

goals. For instance, while psychodynamic approaches

are helpful for gaining insight in the intra-psychic

experiences of the individual, reminiscence and life

review help with creating interpersonal connections.

Behavioral approaches as well as memory training,

on the other hand, are less concerned with the

subjective experiences, but target specific cognitive

deficits. Generally, it is recommended to involve

others in these interventions in order to “increase

social contact, interpersonal communication and

psychological health” (Kasl-Godley et al., 2000).

As dementia progresses individuals experience

memory loss, disorientation and in later stages a loss

of their sense of self. As such, it becomes

increasingly difficult for them to engage in

meaningful activities, although this is of high

importance for their quality of life (Wood et al.,

2009). „It is argued that reminiscence may be

particularly important for demented individuals’

psychological health given that the progressive

deteriorating nature of the disease erodes the ability

to achieve present successes and makes individuals

increasingly dependent on past accomplishments for a

sense of competency“ (Kasl-Godley et al., 2000).

Since remote memory is usually spared for large parts

of the dementia process, people are often able to

recall events from the past. Furthermore, abilities like

sensory awareness (response to stimuli like visual,

audio and tactile), musical responsiveness and

emotional memory (ability to experience rich

emotions) are thought to persist in dementia (Lawton

et al., 2000), making reminiscence through audio-

visual and tactile media possible. Even while

processing memories may be compromised due to the

brain damage, reminiscence can still provide structure

in developing relationships or engaging with others

(Woods et al., 1992).

2.2 Technologies in Reminiscence

Therapy

A recent literature review (Lazar et al., 2014) on

technologies used in reminiscence therapy points to

many research projects in which ICT was used, e.g. in

the form of displaying media on touch screens or

projections. The purposes of using technology in

reminiscence, as analyzed by Lazar et al. are two-

fold: either to account for deficits such as motoric

problems or memory loss or to harness strengths,

such as emotional memory.

One big project in the area is the the CIRCA

project (Gowans et al., 2004), in which researchers

created a multimedia application using video, photo

and music to support one-to-one reminiscence

sessions. The interface was meant to be used by

caregivers initiating conversations with people with

dementia. The authors reported positive results from

user testing. More recent work of the same research

team (Alm et al., 2009) focused on multimedia for

leisure. For instance, computer-generated 3D

environments provided means for people with

dementia to enjoy environments they once liked, but

cannot visit anymore, e.g. a garden or a pub.

Similarly, (Siriaraya et al., 2014) utilized immersive

3D technology, in particular Unity3D and the Kinect,

to create environments for reminiscence and

meaningful activities (like gardening). However,

people with progressed dementia had problems with

the interaction. Lazar and colleagues (2014) found

that “[c]hallenges include that many of the systems

described in the study require technical expertise for

setup or operation and may not be ready for

independent use.” We would like to address this

specifically in our project by designing tangible

everyday objects that hide the technology in a way

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

192

that users do not need any technical expertise and

people with dementia can interact with them without

support.

2.3 Tangible Computing for Seniors’

Reminiscence

Although it has already been recognized (Waller et

al., 2008) that tangible computing is a way to

approach a person-centered model for designing

technology for seniors, the exploration of tangible

computing within the area of reminiscence is so far

limited to a handful of examples that we briefly

outline.

One of the early works on using tangible

interfaces designed specifically for older adults to

trigger reminiscence was Nostalgia (Nilsson et al.,

2003), which consisted of an old radio and an

interactive textile runner with a diamond pattern. The

runner was augmented with hidden switches that

could be pressed to select music and news from

different timespans ranging from 1930 to 1980. A

preliminary evaluation showed that people at the care

home were able to interact with the device and that it

triggered discussions about the old news and singing

along with the music. The television was another

familiar medium, which was deemed suitable for

broadcasting information for reminiscence to people

in a care home. For instance, Waller and colleagues

(Waller et al., 2008) designed a television that

extended the regular TV program with specific care

home internal and personal programs. The TVs were

installed in the rooms of the residents as well as the

communal rooms to allow for private reflection as

well as communication between residents about the

programs, which showed among others, old TV

series, pictures from the care home and events, and

personal photographs. In the unstructured

evaluations, the authors found some proof that people

used the TVs and also discussed the contents.

However, especially people with dementia had

problems using the standard remote controls. For one

such person a tangible remote in form of a photo

frame was built. This could be used by the person, but

was rarely approached by her without a caregiver.

More recent work targeted specifically to people

with dementia was done by Wallace and colleagues

(Wallace et al., 2012) (Wallace et al., 2013). In the

"Tales of I" project (Wallace et al., 2012) they

designed a system comprised of a wall cabinet

holding several snow globes that encased objects

relating to topics like soccer, holidays or local and a

television cabinet with a mold to hold a globe.

Through RFID tags in the globe the TV could read

the correct topic and start the corresponding film.

Films were created from footage ranging back to the

1930s. In addition, personal content for each client

could be played via a USB stick. In this project

authors found that in the hospital setting, where the

system was installed in a common living room, it

provided a sense of home for clients and visiting

relatives, which was often lacking in the sterile

rooms. Through a sense of home and familiarity

anxiety and challenging behaviors could be reduced.

In addition, staff members were able to see a client

more as full person, when that person reconnected to

a sense of self through the films.

In the "Personhood" project (Wallace et al., 2013),

in-depth research into the lived experiences of people

with dementia was done through designing probes

with and for a couple, in which the wife suffered

from dementia. Based on this research interactive

jewelry was designed for reminiscence and providing

a sense of self, through old media (like personal

photographs in a locket) and personalized tangible

artifacts (like a brooch made of old dresses).

These projects were exploratory inquiries into

how tangible computing can be used to trigger

reminiscence, and through that support a sense of self

for people with dementia. Inspired by these works our

work focuses more strongly on developing a medium

that can be used equally by caregivers and people

with dementia in reminiscence sessions, and can be

personalized to care home residents.

2.4 Augmented Books

Within HCI the idea of augmenting books with sound

or video is not new. For instance, “Books with

Voices” (Klemmer et al., 2003) links video

recordings to transcripts of oral histories. This book,

however, needed an additional device to display the

videos. This was also the case with the MagicBook

(Billinghurst et al., 2001), which came with a

handheld AR device to watch additional 3D content

emerging from the pages of the book.

Although studies of the above artifacts show that

the combination of a physical book for easy access

and browsing and the possibilities of additional

multimedia or 3D are beneficial, until now

augmented books have not been used in reminiscence

work for people with dementia.

Our work, however, differs from the above as we

intended to focus the interaction only on the book

itself, and avoid additional technology for accessing

the additional content, as this may be to difficult for

people with dementia.

Reminiscence of People with Dementia Mediated by a Tangible Multimedia Book

193

3 DESIGN CASE: INTERACTIVE

MULTIMEDIA BOOK

3.1 Design Concept

During initial design explorations the project team

engaged in a collection of artifacts that trigger

memories, and field research in dementia care centers

to understand what artifacts were used by caregivers

to stimulate memories in people with dementia. Photo

books, or postcards, were one type of artifacts that

often serve as reminiscence triggers. Images alone,

however, require people to perceive the content

through one sense only, i.e. vision, which can lead to

frustrating situations if the person does not recognize

the content. Music and sound on the other hand, has a

stronger impact on people’s memories, as it connects

to affect. Therefore, we chose for a combination of

images and sound, implemented in an interactive

book (Fig. 1), whereas the sound can be triggered by

the user through simple touch gestures on three parts

of the pages.

Reminiscence content can be very personal;

something that triggers memories in one person does

not necessarily do so in another. Therefore, we

decided to develop the book in such a way that the

contents and the theme of the book can be changed

easily. While the technology is installed permanently

inside the book, the image content is a printed inlay

(Fig. 1 bottom) that can be changed and the matching

sound files per page are stored on a removable SD

card. The book can recognize different inlays through

RFID. Besides the possibility of creating very

personal content, there are themes that refer to a

collective memory of a generation. For the prototype

we chose ‘traveling to Italy’ to exemplify one such

theme. The book consists of five double pages, each

dedicated to another aspect of Italy trips in the

50s/60s. The first double page sets the scene by

showing a map of Italy and playing sounds like

typical Italian music, and street sounds. The second

double page was devoted to the transportation means

showing cars and mobile homes of the time.

Accompanying sounds were the engine roar or car

commercials. The third double page showed a beach

scene with people dressed in 50s beachwear and it

played, e.g., ocean sounds. The fourth page was

devoted to Italian foods like pasta and sounds from

Italian commercials and a song about wine from the

that time. The last double page shows album covers

of typical music of the 50s/60s, which could be

played by pressing on the covers. One famous song’s

lyrics are also printed on that page.

Figure 1: Top: Closed Book, Bottom: Exchangeable inlay.

Figure 2: Hidden Technology. Left: Buttons for audio

output embedded underneath the pages of the book and

magnetic sensors to recognize the opened page. Right:

Arduino and audio board for processing in- and outputs.

3.2 Implementation

The goal was to embed the technology in such a way

that the look and feel of the artifact is so close to a

real book that it would be perceived by people with

dementia as such, and thereby reduce possible

barriers to use. A real book was used with the pages

glued together and small cavities cut out to fit the

technology (Fig 2, right). The book contains an

Arduino Nano V3, which recognizes magnets

embedded each double page through linear Hall

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

194

sensors and is thereby able to identify the opened

page. Furthermore, an RFID reader is built into the

back of the book, which reads the RFID tag of each

designed inlay and thereby enables the exchange of

the book’s contents. Three push buttons are

positioned in the back of the book (Fig. 2, left). On

pressing one of these through the pages of the book

(positions were indicated by green points) a message

containing the selected audio file is sent to an MP3-

player module, which reads the file from an SD card

and outputs it. The book is powered via a mini-USB

port and has a headphone jack to attach external

speakers, as the quality was insufficient with

embedded speakers

4 USER TESTING

4.1 Setting

Dementia care takes place in diverse settings, such as

home care, institutional care and daycare/dementia

support groups. The focus in this paper lies on the

institutional setting, where a majority of people with

dementia resides and caregivers are confronted with

the daily task of engaging with residents in activities.

First, we got in touch with a local welfare

organization. After discussing the project with the

lead social worker in one of their care homes we were

invited to an introductory session involving her and

five caregivers in the care home, who are responsible

for the social care (as opposed to physical care) of the

residents and engage in activities with them, among

these reminiscence sessions, on a regular basis. The

artifact was introduced in this meeting to get

caregivers acquainted with it, discuss an appropriate

set-up and recruit suitable participants. Instead of

defining all study parameters beforehand, we allowed

the caregivers to bring in their own ideas of how to fit

the book into their practice to also derive their own

insights from the user tests. The final set-up was

agreed upon together. For instance, while we initially

intended to have test participants suffering all from

the same level of dementia (i.e., first stage), the

caregivers saw more value in trying the book with a

range of people with different degrees of dementia. In

fact, they were very curious if it worked with people

with advanced dementia. We did not see this as a

problem in the study, since we chose for a qualitative

methodology and did not expect to be able to

generalize the findings over the whole population of

people with dementia. Another discussion point was

the setting in which the book was presented. We

agreed on using different communal rooms in the care

home depending on where each resident would be

most comfortable. However, caregivers commonly

use additional decorations in the room to induce a

certain atmosphere linked to the conversation theme.

We agreed not to do this, since we did not want the

effect of the book diffused by other props.

4.2 Participants

In total, eight people with dementia (1 male, 7

female, aged 80+) and four caregivers took part in the

study. The lead social worker attended all sessions

and took notes for her keeping. Participants suffered

from different levels of Alzheimer’s. Additional,

handicaps such as mobility problems, hearing

problems, speech impairments (related to strokes) and

tremors also occurred (see table 1).

Figure 3: Participants interacting with the book.

Table 1: Participants Details.

# Gender Characteristics

1 female wheelchair, no glasses,

slightly impaired hearing and

vocal articulation

2 female wheelchair, slight vision

impairment

3 female wheelchair, shaky hands

and torso, motoric problems

4 female wheelchair, apathetic

5 female wheelchair, impaired

hearing, shaky hands

6 female wheelchair, one arm is

paralyzed, speech impairment

7 female wheelchair

8 male wheelchair

4.3 Materials and Data Collection

We used the interactive book with an external battery

pack and miniature speaker. We were not allowed to

do video recordings, as this was seen problematic

Reminiscence of People with Dementia Mediated by a Tangible Multimedia Book

195

with people with dementia, especially in the first

stages, as they can be very suspicious of camera

equipment. Therefore, sound recording was done

through a smartphone and additional information was

collected in observations using an observation

scheme to guide the observations according to

interactions with the book, interactions between

people, and physical reactions of participants.

4.4 Procedure

We first briefed the caregivers in how the book works

and informed participants of the study conditions.

Informed consent was provided by care workers, also

on behalf of the people with dementia.

4.4.1 Reminiscence Sessions

In each session, one caregiver engaged a resident and

they looked at the book together, while two

researchers took observational notes sitting at a

separate table in the room. Caregivers were instructed

to engage with the participant as usual and use the

book as they would use other materials in

reminiscence sessions. Sessions lasted between 15

min and 30 min depending on when the person with

dementia wanted to stop. After each session we asked

the person with dementia for some spontaneous

feedback.

4.4.2 Focus Group with Caregivers

After the sessions we were curious about the

caregivers’ feedback. For this purpose we ran a 70-

min focus group with all four caregivers and the lead

social worker. Questions were prepared relating to

spontaneous feedback from the sessions,

communication normally and compared to using the

book, media normally used in reminiscence, other

topics for the book, interaction with the book, and

improvements. However, the set of questions served

us only as a guide, and was not strictly followed.

4.5 Data Analysis

The collected data was analyzed using a qualitative

content analysis (Schreier, 2012). All audio-

recordings of the sessions were transcribed verbatim

in the first step. The transcripts were then

complemented with field notes from the observation

about people’s interactions with each other and with

the book, as well as emotional expressions, gestures

and posture. A coding frame was developed in a two-

step procedure, (1) the higher level codes were

concept-driven based on the focus of our observation

of the sessions (Reaction of PWD (person with

dementia), Reaction of Caregiver, Interaction of

PWD with book, Interaction of Caregiver with Book

and Communication between both), and (2) sub-

codes were based on reading the transcripts.

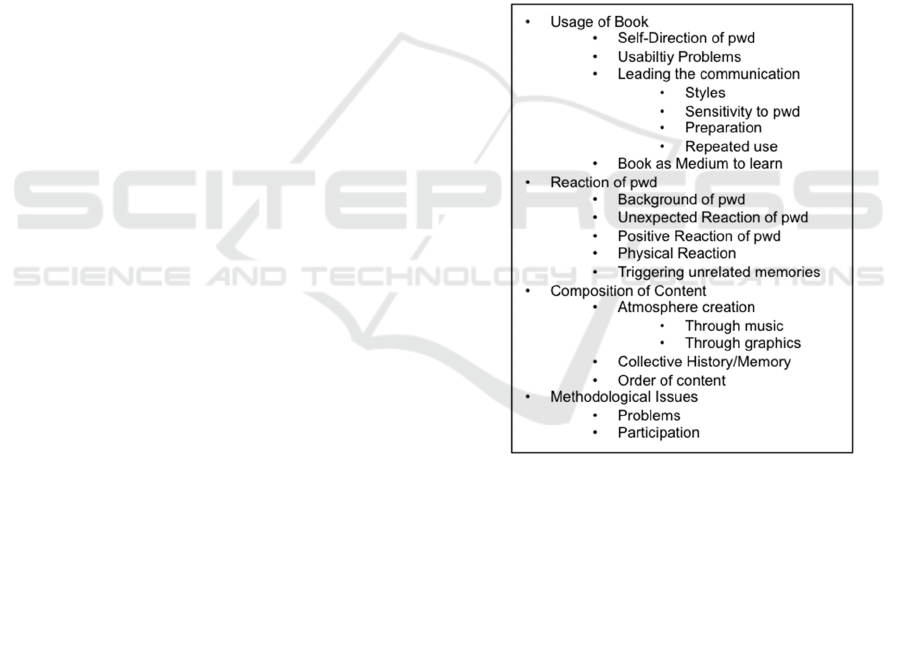

The data of the focus group with the caregivers

was coded directly in a data-driven way, as the

themes/questions used in the focus group were not

followed strictly. After an initial coding of the

complete transcript, codes were categorized in the

tree structure shown in Fig. 4. After coding all data

two researchers discussed and derived higher-level

themes from the coding combining results from the

single sessions and the focus group. Next, we provide

our findings by elaborating on the themes

exemplified through quotes (translated from

German).

Figure 4: Data-driven Coding Frame for Focus Group.

5 FINDINGS

5.1 The Book as an Interaction Device

The book afforded several actions including touching,

turning pages, pressing on pages (to trigger sound),

viewing pages, reading text on pages. We observed

that most of the time the caregiver turned the pages.

However, some interesting exceptions occurred, e.g.

when P3 did not want to listen to the sounds anymore

and went to the next page by herself to make the music

stop. This example shows that the book empowers

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

196

people with dementia to take initiative in steering the

output of the book and thereby the conversation.

With regard to pressing the buttons to play back

sounds, we observed a diversity of reactions of the

residents. Some were curious and pressed the buttons

themselves without an invitation by the caregivers. The

majority, however, waited until the caregiver asked

them to push another button. None of them seemed to

be afraid of the technology or refused it completely.

P3, however, stated clearly that she did not want to

push anymore, which may be related to the problems it

had caused her to hit the buttons correctly. P5, the only

man, pressed the buttons mainly himself and figured

out without explanation that he could stop the music by

pressing a button a second time.

5.1.1 Usability Problems

During the sessions several usability problems were

observed. Many participants were sitting in

wheelchairs, which made it difficult to get close to

the table and the book lying on the table. Since the

book was rather heavy, people could not easily put it

in their lap or lift it. Some were leaning forward to be

able to read better. In several cases, caregivers lifted

the book up a little by putting other books underneath

the backside. In two occasions people had trouble

hitting the buttons, P3 due to a tremor and P8 due to

perception problems (she sometimes mistook other

circles on the pages for a button). When the sound

was too quiet some participants pressed the button

again, which, however, stopped the music altogether

causing confusion.

In some cases pages stuck together. Generally, it

was advised to have thicker or laminated paper,

which would also be more hygienic in the care

setting. When participants reached the last page of the

inlay they tended to try to turn the page, as the book

gives the impression that there are more pages.

Caregivers also criticized the clutter of the graphics

on some pages, which confuses people with

dementia, and suggested to use fewer images per

page and add additional textual information instead.

Text should generally not be used as a graphical

element (e.g. some background texts in Italian),

because people tend to read them and get frustrated if

they cannot understand them.

5.2 The Book as a Medium to Support

Reminiscence

5.2.1 Types of Memories and Triggers

Several types of memories could be observed. Some

were of factual nature in response to something in the

book, either triggered by an image (“Yes, that is like

a camper, they had those trailers and they slept in

them, when they drove to Italy.”), a sound (“Do you

know what you can do in San Remo? Go to the

casino!”) or a question of the caregiver (“Did you use

that [Fondor]”–“My parents, yes”).

Others were more personal narratives triggered

by an image or sound. “Right, these are tomatoes.

Also typically Italian, right?” (CG4) … “They also

grow in Turkey” (P8). “Yes”(CG4) “They were

hanging on the trees, I saw it. We were even allowed

to pick them and eat them. They allowed it. On the

street there were also small peaches or something that

we were also allowed to pick.” (P8)

In two cases memory chains were triggered by the

book’s content that led to memories or complete

narratives that were unrelated to Italy. In the case of

P2 a sound that was interpreted by her as zither music

made her think of a country (Austria). She could

unfortunately not remember the country’s name, and

started talking about Peter Alexander (a famous

musician from Austria). Once the caregiver dropped

the name Austria, the person continued talking about

her ski vacations there. Similarly, P8 started telling

stories about her trips to Norway even after the

session with the book ended. According to the social

worker the book still achieved its purpose to trigger

memories in these cases.

5.2.2 Searching for Help

We observed that in some cases people looked at the

texts to remember something, e.g. in case of the Isetta

car (logo in the book) or when a song was playing

that had the lyrics printed in the book. P2 also pressed

a button for supportive sounds when the caregiver

asked a question: [P2 reads] “A trip across the Alps.

Messerschmidt. That reminds me of something”

“Yeah? Of what” (CG2) [P2 ignores the question and

presses another button on the page.]

5.2.3 Emotional Reactions

Especially the music acted as a trigger to affective

memories. One of the last songs was outstanding, as

every participant knew it and even people with

speech problems sang along. P5 even started crying

during this song, which was interpreted by the

caregiver as a sentimental, but still positive

reminiscence. Other reactions to the book were

laughing together. P2 made many jokes and was

generally very talkative, but also others, who were

more reserved, like P5 or P6, joked at some points in

reaction to the images. It was also common for people

Reminiscence of People with Dementia Mediated by a Tangible Multimedia Book

197

to sigh in what could be interpreted as a sentimental

way, especially after enjoying the music, which may

have brought up memories.

5.3 The Book as a Medium to Support

Communication

As we did not set up the study to compare

reminiscence sessions with and without the book in a

within-subject set up, we rely on the accounts of

caregivers about the mediating power of the book in

the communication. Especially the focus group

revealed the difficulties of engaging people with

dementia in activities. “And Mrs S. is also difficult. It

is hard to connect to her, she is very introverted and

impulsive.”(CG2) “Normally, she does not go to any

activities. She mostly stays in her room with her

roommate and is very hard to get out.”(CG3) Several

caregivers reported that they were very surprised that

the residents were willing to come along and even

seemed to be engaged and enjoy looking at the book

together.

One caregiver told us that the book acts as a

medium to learn something about the other person

and their time. „And you learn something about the

people, depending on what they react to, then you

know their preferences. In that sense it was exciting,

how the people would react. Just asking someone you

don’t find out very much. But with such a medium, I

wished to just see their reactions.“ (CG2)

5.3.1 Styles of Leading the Communication

with the Book

We observed two apparent styles of using the book in

a conversation. Some caregivers directed the

conversation strongly through asking questions

closely related to the content (e.g. What is this sound?

Which image do you like?), while others left it open

to participants to react and engaged in a more natural

conversation. We noticed that in the first cases,

conversations quickly led to a question-answer turn

taking, in which people with dementia seemed less

engaged, but rather briefly answered the posed

questions, while less questions led to more engaged

conversation, as the following excerpts exemplify:

[Fondor Commercial plays] “As in the old

days”(P1) “As in the old days?”(CG1) “Yes, Fondor”

(P1) “Did you use that?” (CG1) “My parents, yes”

(P1) “To spice up food? What kind of food?” (CG1)

“Everything.” (P1) “Pasta?”(CG1) “Yes, yes, pasta,

too, of course.” (P1)

[Fondor Commercial plays] “Enjoy your meal!

Do you know Barilla?” (CG3) “Mmhh, pasta.”(P5)

“Pasta! I know you like Spaghetti.” (CG3) “No, not

Spaghetti. I don’t always have scissors on me!” (P5)

“What? But with lots of tomato sauce.” (CG3) “Yes,

with sauce. Yes, mmh, tomato sauce.” (P5) “Yes, that

is something simple you can make quickly. And then

a glass of red wine with it.” (CG3)

In the case of P2 we also observed a playful back

and forth between her and the caregiver ordering each

other to press a button, then guess what the sound is.

In this case the book clearly facilitated an equal turn

taking in the conversation and a playful engagement

between the two.

The lead social worker added in the focus group

that she could imagine more storytelling from the side

of the caregiver in response to the book, which could

in turn animate the person with dementia to tell

stories, too. This style was, however, not observed in

the sessions, which was due to the fact that caregivers

felt that they should not intervene too much in this

way. CG3 insisted that it would be helpful to have

more time and background information about the

different aspects of the book (like the sounds or

details about the cars) before using it in a session, and

that telling own stories would become easier with

more preparation, too.

5.4 Composition & Atmosphere

Creation

An important theme that came from the focus group

was the composition of the book’s content in order to

create a certain atmosphere. Caregivers told us that

this is very important for people with dementia in

order to reminisce. Therefore, they often use extra

decoration as well as food or smells for people to

experience in such sessions. In this case one could

think of red wine and pasta to taste, lemons to feel

and smell, etc. Caregivers evaluated the last page of

the book (Fig. 3) with the music, and fitting graphics

that infer an atmosphere very positively. They

suggested that this or a similar page should be placed

at the beginning of the book to set the scene and get

people in the right mood.

Furthermore, it was discussed to include music on

each page, to guide the person through the book while

maintaining the feeling. Further ideas were scented

papers or papers with textures to give haptic

feedback.

5.5 Accounting for the Individuality of

the Resident

During the sessions we could observe that the

caregivers were very sensitive to the reactions of the

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

198

participants, even if the cues were very subtle. In one

case, for instance, we thought P8 seemed very

disengaged while a song played, but in the focus

group the caregiver (CG4) reported that the woman

was still tapping her finger a little bit to the music and

therefore left it playing. In another case, a participant

started crying while the music played. In the focus

group CG3 reported the following: “I thought should

I stop it, but that was a nice memory, sentimental, but

nice, and then I thought, I would let her enjoy it,

although it is sad to reminisce.” Being sensitive to the

person is often only possible if one knows the

person’s background well enough. “Mrs S. trembles a

bit and she is incredibly embarrassed about it,

because she is very proud. That is why I asked

‘should I do it?’ just to relieve her. Not to do it for

her, but because I know she would be embarrassed, if

she was trembling and it did not work.” (CG2)

Knowing the person’s background is also crucial

to interpret their reactions. In several occasions we

thought participants were disinterested, negative or

even aggressive, but in most cases the participants

said in the end that they liked the book and the

caregivers reported that certain reactions are normal

for the participants. “Well for being her, she actually

concentrated long on this. She is rather sour and

rejects a lot.” (CG4) “That is her way. In the same

way she can tell you trembling and screaming ‘Yes,

of course, I would like to go outside!’” (CG2)

The sessions also showed that even though the

theme was about Italy, the variety of the content

(cars, food, etc.) allowed people to talk about their

own memories, even if they had not visited Italy, as

e.g. in the case mentioned earlier where P8 talked

about Norway instead. In addition, the

implementation of the book also allows for

completely personalized content, as the inlay can be

exchanged.

6 DISCUSSION

6.1 Tangibles for People with Dementia

In the previous section we described many detailed

findings on how people interacted with the book.

From these we would like to highlight three aspects

that proof, in our view, the suitability of tangible

computing for this target group. First of all,

familiarity with the artifact enabled participants to

approach the book without fear and the level of

technical skills did not matter at all. After short

explanations all participants understood the concept

of pressing on the pages to trigger sounds. This was

also not considered strange. Two people with

dementia referred to the book as an audio book or a

talking book. A second aspect we could observe in

the sessions was that the book enabled self-direction

for people with dementia. As described, people used

the functionality of lifting a page or pressing a button

twice to stop the sounds they did not like to listen to

anymore, thereby steering the conversation

themselves. Last, an interesting observation was

made by one caregiver in the focus group regarding

the agency of people with dementia using the book by

themselves to turn on music, as opposed to the

caregiver playing music from a CD player. “But also

[her] surprise, when she pressed for the first time.

This surprise was of course very extraordinary. You

cannot achieve this when you start [playing]

something [music at a CD player] elsewhere. That is

something that only happens when they press

themselves.” (CG3) This integration of input and

output spaces, inherent in tangible computing,

seemed to trigger emotional reactions in the

participants that traditional technology is not able to

trigger.

6.2 Design Recommendations

From the findings of the study we recommend the

following design considerations for interactive

reminiscence books:

• Make the book more manageable by reducing

original (unused) pages and weight.

• Use few and distinct images on the pages to avoid

clutter.

• Provide buttons with different texture than the rest

of the page and bigger surfaces.

• Start with a page that creates an atmosphere to set

the scene by using music and possibly other sensual

output like scents.

• Add information to the visual content (mostly for

caregiver as background information).

• Increase reminiscence potential through emotional

content like music or poems.

• Provide contents people with dementia can easily

relate to, e.g. local things or content linking to

collective memories of the generation (e.g. TV

shows).

6.3 Limitations

Drawing generalizable conclusions from the sessions

on how a medium like the book works for people

with dementia is hard due to the inherent diversity of

Reminiscence of People with Dementia Mediated by a Tangible Multimedia Book

199

symptoms, personalities, and capabilities of the target

group. This, however, is not specific to this study, but

rather a general concern in doing qualitative field

research with people with dementia, since the disease

develops differently in people depending on which

brain areas are affected. Although we did ask people

with dementia to give us direct feedback on their

experience, some were too tired or had forgotten parts

of the content already. In these cases we have to rely

on our observations and caregivers’ accounts on how

to interpret the reactions. Another limiting factor in

this respect is the lack of video recordings, which

would have allowed us to look back at certain

reactions with the caregivers.

Overall, the observations need to be interpreted in

the context of interaction styles of caregivers and

backgrounds of residents (see Findings). Yet, we

believe that the rich accounts of the qualitative data

give many insights into the role of tangible

multimedia in this setting.

6.4 Future Work

In accordance with the findings on the usability of the

book, we intent to implement the recommendations

described above including making it less heavy,

increasing the button size and changing their texture,

using scented paper for additional sensual output, as

well as improving the graphics and general

composition of the content. In addition, the book was

created in a way to allow for easy switch of content.

Together with the caregivers we explored which

content would work best for reminiscence sessions

and we identified, besides others, two themes for new

content: local content about our city (including, e.g.,

traditional events) and a TV theme including TV

moderators/actors, shows etc.

7 DISCUSSION

We investigated the use of tangible multimedia in

reminiscence with people with dementia. In

particular, we presented a design case, i.e. an

interactive book that can be operated by people with

dementia and their caregivers created with the goal to

support memories from the past through images and

associated sounds. In the field study we found that the

book had potential to act as a medium for

reminiscence and communication between a caregiver

and resident. Some usability problems were found

and design recommendations provided to mitigate

those. Overall, we observed that people had no

hesitation to approach the device and people with

dementia were empowered to steer the conversation

pointing to a great potential for tangible interfaces in

this domain. Especially, given the importance of

psychosocial interventions for people with dementia,

their lack of technical knowledge and the new

possibilities tangible UIs offer, we should consider

the combination of digital multimedia content and

familiar physical objects as an effective way to

improve therapy with people with dementia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is funded by the local government of

North-Rhine Westphalia, Germany and was executed

as part of the “NutzerWelten (UserWorlds) – User-

Centred Design of social technical environments for

people with dementia” research program at the

University of Applied Sciences Düsseldorf. We thank

the developers of the book Amelie Ritter and Jörn

Hornig and the employees and residents of the

Joachim-Neander-Haus, Diakonie Benrath,

Düsseldorf.

REFERENCES

Alm, N., Astell, A., Gowans, G., Dye, R., Ellis, M.,

Vaughan, P., Riley, P., 2009. Engaging multimedia

leisure for people with dementia. Gerontechnology

8(4), 236-246.

Alzheimers.Net,

www.alzheimers.net/resources/alzheimers-statistics/,

accessed December 2014.

Billinghurst, M., Kato, H., and Poupyrev, I. The

MagicBook: a transitional AR interface. Computers &

Graphics 25, 5 (2001), 745–753.

Casey, D.A., Antimisiaris, D., O’Brien, J.Drugs for

Alzheimer’s Disease: Are They Effective? P T. 2010

Apr; 35(4): 208–211.

Gowans, G., Campbell, J., Alm, N., Dye, R., Astell, A.,

Ellis, M., 2004. Designing a multimedia conversation

aid for reminiscence therapy in dementia care

environments. In CHI'04 Extended Abstracts on Human

Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 825-836). ACM.

Kasl-Godley, J., Gatz, M., 2000. Pschosocial interventions

for individuals with dementia: an integration of theory,

therapy, and a clinical understanding of dementia.

Clinical Psychology Review 20:6, 755-782.

Kitwood, T., Bredin, K., 1992. Towards a theory of

dementia care: personhood and well-being. Ageing and

society 12(03): 269-287.

Klemmer, S.R., Graham, J., Wolff, G.J., and Landay, J.A.

Books with voices. Proceedings of the conference on

Human factors in computing systems - CHI ’03, ACM

Press (2003), 89.

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

200

Lazar, A., Thompson, H., & Demiris, G. (2014). A

systematic review of the use of technology for

reminiscence therapy. Health education &

behavior, 41(1 suppl), 51S-61S.

Lawton, M. P., & Rubinstein, R. L. (Eds.). (2000).

Interventions in dementia care: Towards improving

quality of life. New York, NY: Springer.

Nilsson, M., Johansson, S., & Håkansson, M. (2003, April).

Nostalgia: an evocative tangible interface for elderly

users. In CHI'03 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors

in Computing Systems (pp. 964-965). ACM.

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in

practice. Sage Publications.

Siriaraya, P., Ang, C. S., 2014. Recreating living

experiences from past memories through virtual worlds

for people with dementia. In Proceedings of the 32nd

annual ACM conference on Human factors in

computing systems (pp. 3977-3986). ACM.

Van der Linde RM, Stephan BCM, Savva GM, Dening T,

Brayne C: Systematic reviews on behavioural and

psychological symptoms in the older or demented

population. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy 2012, 4.

Wallace, J., Thieme, A., Wood, G., Schofield, G., Olivier,

P., 2012. Enabling self, intimacy and a sense of home in

dementia: an enquiry into design in a hospital setting. In

Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2629-2638). ACM.

Wallace, J., Wright, P. C., McCarthy, J., Green, D. P.,

Thomas, J., & Olivier, P. (2013, April). A design-led

inquiry into personhood in dementia. In Proceedings of

the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems (pp. 2617-2626). ACM.

Waller, P. A., Östlund, B., Jönsson, B., 2008. The extended

television: Using tangible computing to meet the needs

of older persons at a nursing home. Gerontechnology

7(1): 36-47.

Wood, W., Womack, J., Hooper, B., 2009. Dying of

boredom: An exploratory case study of time use,

apparent affect, and routine activity situations on two

Alzheimer’s special care units. American Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 63(3): 337-350.

Woods, B., Portnoy, S., Head, D. Jones, G., 1992.

Reminiscence and life review with persons with

dementia: Which way forward? In G.M.M. Jones &

B.M.L. Miesen (Eds), Care-giving in dementia:

Research and applications, 137-161.

Reminiscence of People with Dementia Mediated by a Tangible Multimedia Book

201