Incorporating Cultural Factors into the Design of Technology to

Support Teamwork in Higher Education

Wesam Shishah

1

and Elizabeth FitzGerald

2

1

School of Computer Science, University of Nottingham, Wollaton Road, NG8 1BB, Nottingham, U.K.

2

Institute of Educational Technology, The Open University, Walton Hall, MK7 6AA, Milton Keynes, U.K.

Keywords: Culture, Group Work, Teamwork, Higher Education, Design, HCI, CSCW.

Abstract: Online teamwork is an instructional strategy widely used in education courses to ensure active knowledge

construction and deeper learning. There is a challenge for online course designers and technology designers

to create group environments that encourage participation, and have the ability to enhance positive attitudes

toward group work. It is hypothesised that incorporating cultural factors into the design of teamwork

technology has the potential to encourage participation and increase students’ positive attitudes towards group

work. This paper looks to do exactly that, although the definition of culture in this paper is limited to the

individualism–collectivism dimension. The paper summarises our findings from interviews conducted with

lecturers and students who have experience with teamwork. It then presents culturally-related design strategies

which are identified from cross-cultural psychology literature and our interviews finding. Finally, it

demonstrates how culturally-related design strategies are incorporated into the IdeasRoom prototype design.

1 INTRODUCTION

The inclusion of group work into course work by

educators within higher education is becoming more

frequent, because of the current view that teamwork

is an essential skill that students need to develop

(Drury et al. 2003). Students gain a number of

educational, social and practical benefits by being

engaged in group work (Goo, 2011). To promote

positive attitudes and encourage students to

participate in group work, an effective group work

environment needs to be created, which is a challenge

for technology designers and online course designers.

Research studies suggest that students work more

effectively in group work situations if they perceive

teamwork positively, as behaviour is often predicted

by attitudes; however, the way that individuals

interact with their environment and with others is

often governed by shared learned patterns of

behaviour and belief, so that culture strongly

influences behaviour and attitudes (Mittelmeier et al,

2015; Triandis 1995; Hofstede 1996). Currently,

there is insufficient research on how technology could

support the effectiveness of teamwork in terms of

focusing on how culture could enhance attitudes

towards teamwork more positively, or the role of

culture in encouraging students to participate in

teamwork.

This paper discusses the approach taken to

support teamwork for students within the design of

technology used that incorporates cultural factors,

which is achieved in three stages. Within an academic

context, relevant cultural factors associated with the

practice of teamwork are explored by conducting

interviews, which forms the first stage of this work

and is described in more detail in Section 5. Insights

from the interviews, as well as findings from cross-

cultural psychology literature on the bipolar

dimension of individualism-collectivism are

evaluated to identify design strategies in Section 6,

which forms Stage 2. Section 7 describes Stage 3,

which discusses how these design strategies are

adopted for the prototype design, named IdeasRoom.

2 MOTIVATION FOR THE

RESEARCH

Due to the increasingly multicultural character of

students in higher education, it is important for online

course designers to understand the role that culture

plays in academic teaching.

Several studies in the areas of cross-cultural

Shishah, W. and FitzGerald, E.

Incorporating Cultural Factors into the Design of Technology to Support Teamwork in Higher Education.

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2016) - Volume 1, pages 55-66

ISBN: 978-989-758-179-3

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

55

behavioural and cognitive psychology found that

one's culture determines how we process information

(Kim 2013). In Human Computer Interaction (HCI),

there has been only limited research on the effects of

cultural differences on information processing and

online interactions. Instead, researchers have tended

to focus on users’ external behaviours, rather than

their internal cognition. However, we propose that an

understanding of cultural differences will benefit

designers in the development of cost-effective

systems that serve both ‘domestic’ students and

multicultural groups.

In this research, we propose a novel approach that

is culturally personalised in a group-based system in

higher education. The motivation for this approach is

to establish a culturally related group-based tool to

aid collaborative work carried out by multicultural

student groups. This led to the development of a

prototype system called “IdeasRoom”, to investigate

this proposal and demonstrate a culturally

personalised approach to collaboration. This paper

details the first phase of research by exploring the

differences between how individualists and

collectivists process information through group work.

3 CULTURAL DIMENSIONS

In this study, we focus on two common societal

dimensions of culture: individualism and

collectivism. We define these as follows:

• Societies described as individualist tend to be

mainly associated with their close families and

often live independently, so that they are expected

to look after themselves; therefore, there are loose

ties between individuals. People living in

individualist societies tend to be motivated by loss

of self-respect and guilt, and are often perceived

to be goal-oriented and self-motivated, so that

group interests are less important than individual

interests (Hofstede, 2010; Hofstede, 1996).

People living in individualist societies tend to

demonstrate a personal identity rather than an

identity of specific groups, so that they often seek

benefit from their duties and activities, and have a

more consistent behaviour and attitude approach

to life than those from collectivist societies

(Triandis, 1995).

• These findings are contrasted with societies

described as collectivist, where people tend to

form groups that are cohesive and strong

throughout life, so that the welfare of individuals

becomes the concern of the group associated with

them, and anxiety can result when individuals are

separated from their group. Unquestioning loyalty

is shown to individuals in collectivist societies, as

the groups they are associated with, and often

known as ‘in-groups’, give them protection when

needed. Generally, people in collectivist societies

attempt to maintain tradition, adopt virtues and

skills that are needed to demonstrate that they are

good members of their group, and attempt to

maintain social harmony, so individual interests

are less important than group interests. Therefore,

people living in collectivist societies tend to be

motivated by loss of face and shame (Hofstede,

2010; Hofstede, 1996). The identities of

individuals in collectivist societies are usually

associated strongly with the values of their group,

so that they generally support what is acceptable

in their group (Triandis, 1995).

The main focus of individualism and collectivism

is how individuals are integrated within groups.

Therefore, this research focuses on peer group

interaction with individuals from different cultures,

within a group-learning environment.

Although this categorisation of societies is widely

supported in the literature review, the definition of

cultural identity involves greater complexity than

factors discussed above, as individuals in all societies

are likely to demonstrate various cultural identities at

different times and in different circumstances. We

present only one perspective on how to examine

culture and there are others that we could draw upon.

However, to form a concept of different groups in

terms of their behaviour patterns and general belief,

the individualism-collectivism dimension proposed

in previous research studies provides a very useful

and important initial categorisation on which to

ground future work.

4 TEAMWORK IN EDUCATION

According to Smith and Bath (2006), the most

effective approach to ensure students acquire

knowledge and enhance their communication skills at

educational institutions is teamwork, as this provides

significant advantages to supervisors and teachers to

reduce the quantity of their marking, give students

opportunities to work collaboratively, enhance the

challenge and complexity of tasks given to students

to improve their experience of working, and to engage

students more effectively (Gibbs, 2009). When

compared with face-to-face collaboration for group

work projects, the performance of students

collaborating online can be significantly better,

because the interactions with other members of the

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

56

group are more meaningful and frequent for students

collaborating online, when compared with students

involved in learning activities on a face-to-face basis

(Tutty and Klein, 2008).

Online learning tasks for teamwork is perceived

more negatively by Smith et al. (2011), who report

that resolving logistical problems is easier for

students seated physically together in one room, when

compared to students learning in online classes.

Personal factors can influence the perception of

teamwork by students, so that how they perform

within group activities is affected by this perception.

Perceptions of group work by students might also be

affected by their communication and personality

traits (Myers et al., 2009), but this is challenged by

findings from other research, which suggests that the

previous experience of students working in groups

could change their perception of teamwork through

online channels. In a study by Powell, Piccoli and

Ives (2004), the findings report that when students

had wider experience of working with other students

online and were involved in more online courses,

their perceptions of teamwork through online

channels were increased positively. This was related

to the students spending more time online, and using

this time to adapt to (and benefit from) the technology

and online teamwork activities.

Research studies evaluating behaviour and

teamwork preferences for employees and students

suggest that the cultural dimensions of individualism

and collectivism developed by Hofstede are an

important factor in terms of profiling such groups and

a useful way of assessing group behaviours (Bishop

et al., 1999). When students work collaboratively in

groups, their working processes are likely to be

different, due to differing approaches that are likely

to be taken by students from primarily individualist

versus primarily collectivist cultures (Galanes et al.,

2004).

5 CULTURE IN DESIGN

The link between individuals’ interactions with

technology, and their culture, has become a focus for

an evolving field of research. HCI approaches can

utilise Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, borrowed

from the field of sociology, to investigate how aspects

of culture influence our interactions with technology

(Hofstede, 1996). Evers (2001) investigated interface

metaphors from a perception of cross-cultural

understanding, and Vohringer-Kuhnt (2001)

investigated perceptions of usability by people and

the influence of culture, where both studies relied on

cultural dimensions in HCI investigations. However,

there is an insufficient focus in the literature on how

teamwork could be supported by examining the

relationship between technology and culture.

Designers of technology tend to adopt cultural

aspects of day-to-day life when adapting design

preferences for technology products, as this is an

important factor for consideration, and the strategies

adopted by designers are embedded and used in their

products. Design decisions are often based on the

value judgement of the designers in terms of

motivating factors used, their belief in what any target

audience could be influenced by, and what influences

them personally (Khaled, 2008). This suggests that

technology designers are likely to embed their own

cultural preferences into their technology products,

but do not sufficiently consider the consumer or

audience that could use these products who might not

associate with these values and ideals. According to

Hall (1989), hidden issues in society are often exposed

when individuals become aware of control systems that

are in place, and this is exposed more frequently during

programmes involving a mix of cultures, and who

reports from an anthropological perspective. Hall

explains that an individual’s personality has cultural

programmes that are internalised, so that people’s

behaviour, attitudes and personalities are based on

these (Hall, 1989). However, these findings could be

transposed to investigations of technology users, as

some could feel dissatisfied by their typical interaction

patterns, their behaviour, their knowledge base or

mismatched assumptions about their identity.

Therefore, behavioural and attitude changes are

unlikely if users are made to feel uncomfortable, and

technology designers need to consider these potential

consequences.

When using technological tools to trigger

encouragement, it is important to recognise and

identify that different users will have different

cultural dimensions, and that their perceptions are

likely to differ. Therefore, the potential effectiveness

of such tools could be increased if designs match the

cultural assumptions of users, as they should be more

comfortable using the technology, concerns would be

reduced, and users can focus their attention on the

content better, which would help overcome the issues

mentioned previously by Hall (1989).

6 EXPLORING CULTURAL

FACTORS IN TEAMWORK

Semi-structured interviews were adopted in this study

in order to explore how students incorporated culture

Incorporating Cultural Factors into the Design of Technology to Support Teamwork in Higher Education

57

as a factor in their current practice of teamwork

activities.

Two groups of participants were recruited for this

study. The first group involved twelve computer

science postgraduate students from a UK university,

who had prior experience of working in groups. The

gender balance of this sample was six females and six

males. Student interviews included topics that asked

about tools usually used for the completion of group

tasks and projects, together with tools used for

communicating with others, evaluating and assessing

the group projects. Advantages and disadvantages,

and problems and issues faced by students working in

groups are also included.

The second group involved five lecturers from the

same university, who teach computer science for

university students at its UK campus and also in its

overseas campuses in China and Malaysia. All

lecturers had prior experience planning and teaching

group activities. The focus of lecturers’ interviews

included asking about their experience with

teamwork activities, how students’ project teams

were formed (whether student, tutor, or randomly

organised), how roles were allocated (no roles, tutor

allocated roles, student chosen roles or all tasks

divided evenly) and whether the groups designated a

leader or not. The lecturers were also asked about

tools or technology used to support student teamwork,

and the strategies used for group work assessment and

students’ feedback regarding the assessment.

The interviews took place in the School of

Computer Science at the university’s UK campus,

where respondents were individually interviewed in a

quiet area. The interview process, the purposes and

aims of the interview were explained to the

participants; the interview time ranged from 30 to 45

minutes. Respondents were asked for their permission

to record the interview, and to sign a consent form

demonstrating their willingness to participate before

the interviews. The researcher explained that

respondents could stop the interview and withdraw at

any time; the interviews were recorded with an audio

recording device for subsequent analysis.

6.1 Analysis

Following the interviews, the audio recordings were

transcribed, resulting in fifty-one thousand words.

Then, the transcripts were qualitatively analysed. A

thematic analysis was adopted in order to identify

underlying patterns and themes of behaviour or living

from text data, to reveal common threads that

emerged from all the responses, as recommended by

Aronson (1994).

An initial phase of analysis was conducted before

thematic coding was applied. This phase consisted of

gathering cross-cultural psychology literature on the

behavioural and motivational differences between

individualists and collectivists. Key motivations from

the literature are summarised in Table 1 and were

then considered as a scientific basis for the thematic

analysis and codes are described in the next section.

Then, thematic analysis was used to analyse the

transcripts in two phases. In the first phase, two

indicators were used (individualistic focused theme

vs. collectivistic focused theme). In the second phase,

four indicators were used, that emerged from the data

and coded appropriately. These two phases is

described in more detail below. The assignment of

statements to categories was done by the main

researcher in consultation with two other lead

researchers, to avoid subjectivity and bias.

Table 1: Individualist and collectivist motivations.

Motivation Individualist Collectivist

Superordinate

goal

Individual goal Sharing goal

Identity

Self-identity Group identity

Trust

Cognition based Affect based

Accountability

Individual based Group based

Communication

Partial channel Full channel

Reward

distribution

Equity based Equality based

Relationship

Competition Harmony

Rules

few rules many rules

6.1.1 Thematic Analysis: Phase 1

Two overarching thematic codes were developed to

use in this phase. The two codes were identified based

on cultural anthropologists’ classification on how

individuals are integrated within groups (Hofstede,

1996; Triandis, 1995) as described in the definition of

individualism and collectivism in the introduction.

The codes are reflected the following classifications:

• IND – Individualism

• COL – Collectivism

Many sociologists such as Hofstede and Triandis

have worked on classifying individualism and

collectivism on two levels – namely, the nationality

and individual level. Hofstede’s research applies the

classification of individualism and collectivism to the

nationality level, while Triandis’s research applies it

at the individual level. Hofstede’s work has often

been criticized because of his classification which

reduces culture to nationality. It also ignores the

ongoing changes that a person or a group who shared

cultural values undergo (McSweeney 2002). In our

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

58

analysis, we relied on the individual level of

classification of individualism and collectivism and

excluded participants’ nationalities.

By the end of this phase, two lists are generated:

the IND list which includes all quotes that refer to

individualistic perspectives and the COL list which

includes all quotes that refer to collectivist

perspectives.

6.1.2 Thematic Analysis: Phase 2

A set of thematic codes was developed to use in

determining the key differences in cooperation

between individualism and collectivism quotes from

the two lists in the thematic analysis phase 1. The

codes were developed by the research team based on

both a grounded analysis of the text and also taking

into account the critical aspects of teaching from the

lecturers’ accounts. The codes reflect the following key

aspects, which highlight notable differences between

students and are explained in more detail below:

• R – In-Group Relationships

•

I – Identity (of the student)

•

N – Assessment Norms

•

G - Superordinate Goals

In-Group Relationships (R) refer to how the

relationship among group members is different

between individualistic and collectivist perspectives.

Identity (I) refers to how the views about self is

different between individualistic and collectivist

perspectives.

Assessment Norms (N) refers to how the individual

perceives the distribution of rewards or marks among

group members and how this may be different

between individualistic and collectivist perspectives.

Superordinate Goals (G) refer to how the goal of the

cooperation will be achieved which is different

between individualistic and collectivist perspectives.

Quotes from the two lists in Phase 1 were then recoded

to identify themes that indicated R, I, N and G. By the

end of this phase, eight lists of quotes are generated and

referred to by the codes given in Table 2.

Table 2: Codes Generated in Thematic Analysis Phase 2.

Code R I N G

IND

IND- R IND - I IND - N IND - G

COL

COL- R COL- I COL- N COL- G

6.2 Results

This section explains the results from the thematic

analysis of Phase 1 and Phase 2.

6.2.1 Thematic Analysis Results: Phase 1

As explained above, the recordings of the interviews

were transcribed and the transcriptions were then

thematically coded looking for quotes relating to

individualistic perspectives and collectivist

perspectives. Table 3 below shows the quotes

frequency that emerged for each code (IND and COL)

in this phase. Broadly speaking, there were some key

differences found between students and these are

explored in the analyses below.

Collectivism was described by both groups of

participants, i.e. both students and lecturers; for

example, the collectivist behaviour that described

students in China and how the interdependency of the

Chinese students influences the strategy of forming

students in groups by lecturers. A typical response

given by one lecturer was “Once we have formed CS

[Computer Science] students together, we form

groups in the way that they live. It is more convenient.

So they absolutely do not need mobiles to

communicate. They come to the lecture together, they

walk together, and eat together.”

Also, a high collectivism perception is

demonstrated in describing students in Malaysia, as

they are seen as more family oriented. A typical

response given by one lecturer was “In Malaysia,

students see their teachers like their parents. Maybe

the culture of the east. The culture is like this, this is

the lecturer and everything is OK, so they do not

argue. Their culture is to do what is the teacher asks.”

This collectivism is demonstrated by students as

well; for example, one student expresses the priority

and the importance of values like harmony and

working together in teams. A typical response was

“It just came to my mind is that it is group work after

all and firstly we should have some harmony. We

need all working together.”

On the other hand, individualism was also

demonstrated; for example, the need for the

evaluation of individual contributions was

highlighted. A typical response by one student was “I

think it’s difficult to mark a group without peer

evaluation, because if you don’t have peer

assessments, you can’t tell he [a particular student]

hasn’t done any work and the group gets all the same

mark. “

Individualism is demonstrated by lecturers; for

example, describing the feature of the student self-

moderators in online groups is the reason for the

success of experience with forums that are not

provided by the university. A typical response given

by one lecturer was “Using forums through Moodle, I

can’t make any students moderators, so they can’t

Incorporating Cultural Factors into the Design of Technology to Support Teamwork in Higher Education

59

appoint their own self-moderators in groups, which I

think is why I have never seen any forum setup using

the university learning system, which has a same kind

of interaction as any other kind of forum that you can

see existing online.”

Table 3: Themes Frequency that Emerged in Phase 1.

(Numbers refer to number of quotes from interview

participants).

Participant IND Theme COL Theme

Student_1 * 8 7

Student_2 ** 4 10

Student_3 ** 0 20

Student_4 ** 8 11

Student_5 * 20 2

Student_6 * 16 3

Student_7 ** 2 17

Student_8 ** 1 7

Student_9 * 19 4

Student_10 ** 5 17

Student_11 ** 2 19

Student_12 * 20 12

Lecturer_1 ** 0 3

Lecturer_2 ** 0 2

Lecturer_3 ** 0 3

Lecturer_4 ** 0 2

Lecturer_5 * 4 0

Total IND/COL 109 139

Total 248

( * indicates that IND themes more than COL themes)

(** indicates that COL themes more than IND themes)

6.2.2 Thematic Analysis Results: Phase 2

In this phase 248 quotes were listed in Phase 1 and

recoded in this phase looking for quotes relating to

indicators relating to in-group relationships, identity,

assessment norms and superordinate goals. Table 4

below shows the quotes frequency that emerged for

the eight codes that were developed for this phase.

Table 4: themes frequency emerged in phase 2 (Numbers

refer to number of quotes from interview participants).

Code R I N G

IND

12 36 35 42

COL

51 49 15 50

Table 5 shows examples of quotes reflecting the

codes used in this phase. The quotes in Table 5 show

how individualists and collectivists differ in the in-

group relationship (R), the quote (COL-R) shows

more harmony and collaboration behaviour while the

(IND-R) shows more competitive behaviour among

group members. Regarding the identity (I), the

comparison behaviour in cooperation explained by

the quotes (COL-I) and (IND-I) shows the differences

between individualism and collectivism in the

identity. The (COL-I) quote demonstrates high

collectivism, as the respondent perceives the self as

the group and compare the group that belong to with

other groups. In contrast, (IND-I) quote demonstrates

high individualism, as the respondent perceive the

self as individual and compare own efforts with other

individuals.

In assessment norms (N), the (COL-N) quote

relates to when students are working in the same

group, but who are dissatisfied when they receive

unequal marks. The (IND-N) relates to students who

are dissatisfied when members of the same groups are

awarded equal marks despite making unequal effort,

which was perceived to be a factor that influenced the

contribution of individuals involved in group work.

Regarding the Superordinate Goals (G), the quote

demonstrates the motivation to achieve the goal of

cooperation in collectivism (COL-G), and shows the

person has a group goal interest. The quote

demonstrates the motivation to achieve the goal in

individualism (IND-G), and shows the person has

more personal goals and interests.

Table 5: Examples of Quotes Reflecting the Codes in Phase

2.

Code Quote

IND-R

“When they come to receive marks back to the

group coursework, students will compare each

other mark and if they believe that their friend get

the mark for something they did not get a mark

for. They are coming ask for that extra mark so

they can have higher grades than friend. They are

very competitive between each other within the

group about the mark they receive.” (lecturer_5)

IND-I

“Sometimes people don’t care what others

contribute so with each person, it differs, but with

me if I see someone else do more work, then it

motivates me to do more” (Student_6)

IND-N

“It’s not fair on the rest of the group who have

done the work whereas someone hasn’t and he’s

got high marks from doing nothing. Our marks

should not be equal” (Student_9)

IND-G

“if there was some way to measure how much I

contribute to the overall work than I will do my

best” (Student_10)

COL-R

“Sometime my friends think that I work hard

looking for extra marks but it is not. I see it is

teamwork and we need work together and

support each other” (Student_7)

COL-I

“Sometimes I will compare our group effort to

others because sometimes I see other group is

more like our group.” (Student_12)

COL-N

“We worked in a group of two and we did all the

preparation together. It’s just that my friend said

the first half and I said the second half; I got a bad

mark even though we did the work together, and

we both felt it was unfair. It is a group work and

we suppose to get an equal marks” (Student_8)

COL-G

“I mean I will try my best to win the competition

for my group.” (Student_11)

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

60

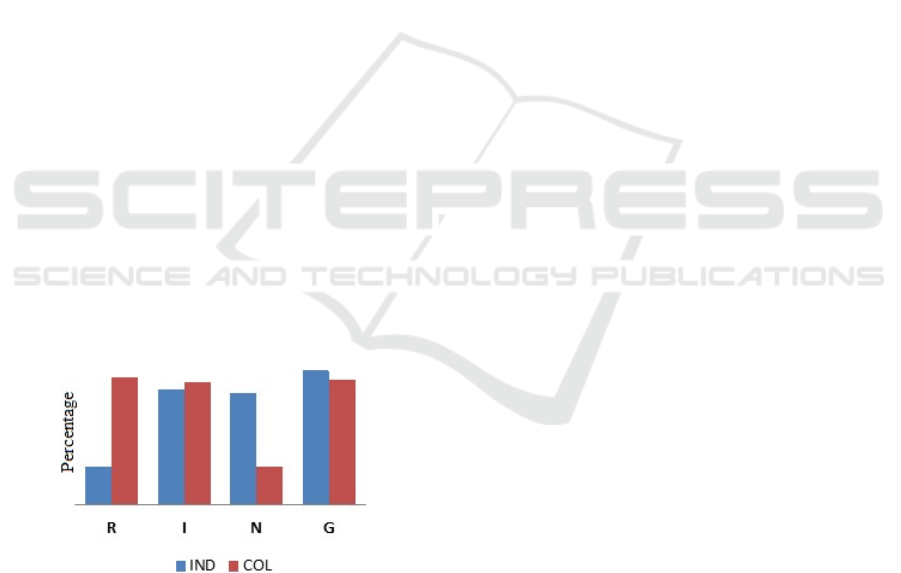

6.2.3 Summary of Results

The analysis shows how two groups of participants

(lecturers and students) reported their views of

individualism and collectivism on teamwork. This

study is in keeping with previous studies such as, Cox

et al., (1991); Galanes et al., (2004); Mittelmeier et al,

(2015) which suggested that individualism and

collectivism traits can predict and influence student

group work behaviours. The findings also show that,

while some students’ have a more dominating

individualistic tendency, others have more

collectivistic tendencies. For instance, five students

report that they have more individualistic perspective

towards teamwork. On the other hand, seven students

show that they have more collectivistic perspectives

towards teamwork (see Table2). With regard to

lecturers, four of them have a collectivist perspective

in teamwork while one lecturer has a more

individualistic perspective.

In the second stage of the interview analysis, we

focused on four key strategies; namely, ‘R’ – In-

Group Relationships, ‘I’ – Identity of the student, ‘N’

– Assessment Norms and G - Superordinate Goals.

The results show that these four keys were found in

both individualist and collectivist perspectives.

However, the percentage was more significant in ‘R’

– In-Group Relationships in the collectivist

perspectives rather than individualist. On the other

hand, ‘N’ – Assessment Norms was more significant

in individualist rather than the collectivist

perspectives. Figure 1 demonstrates the percentages

of the occurrence of the four key strategies in both

individualist and collectivist perspectives.

Figure 1: The percentage of the four key strategies’ quotes

in the individualist and collectivist perspectives.

7 A SET OF CULTURE-RELATED

DESIGN STRATEGIES

To design group-based technologies that are

meaningful and effective for their target audiences,

designers should reference – or at least allow for - the

audiences’ cultures in their approaches. This section

summarises the findings of the interviews carried out

with lecturers and university students who have

experienced group work, to establish how students

incorporate culture as a factor from their current

practice. This section also presents a set of culturally

relevant group-based technology design strategies

based on insights from the interviews, as well as

findings from cross-cultural psychology literature on

behavioural tendencies of individualists and

collectivists.

These strategies have resulted from our work with

the participants mentioned above, and form suggested

approaches when considering the design of

technological tools to support and encourage

effective online team working, particularly when

working with culturally diverse group members.

A set of four main culturally relevant design

strategies is presented and each strategy involves two

sub strategies. One is aimed at use in tools developed

for collectivist users and the other is aimed at use in

tools for individualist users. Each strategy is

presented with the following information:

Description, which attempts to explain the strategy

presented, Antecedents, which highlight the factors

based on the review of the literature that lead to the

strategy, Real World Parallels, which demonstrate

the strategy in real world situations, and The Two

Sub-Strategies produced from each main strategy.

The two sub strategies are presented with a

description and target audience, which suggests

whether the audience would likely to be collectivist

or individualist. This way of describing the strategies

is intended to help designers include appropriate

strategies in systems that are relevant for target

audiences where cultural backgrounds could be a

significant factor. It is anticipated that designers

could find the discussions, descriptions and

antecedents helpful in understanding the strategies,

why they were developed and how they could be

applied.

7.1 Strategy 1: In-Group Relationships

Description: The difference between collectivist

users and individualist users forms the basis of this

overall strategy to define relationships between

members of a group.

Antecedents: In studies of education theory, findings

suggest that individuals from individualist cultures

often display less cooperative behaviour in groups

than those from collectivist cultures, which supports

the views discussed above (Cox et al., 1991).

Collectivists often highly value group solidarity and

Incorporating Cultural Factors into the Design of Technology to Support Teamwork in Higher Education

61

interpersonal harmony, prefer cooperation to

competition, value group success rather than

individual success, and tend to avoid individual

recognition. This contrasts with individualists who

often demonstrate additional effort to attain

individual goals, and are generally motivated by

individual recognition and competition (Triandis,

1994; Cox et al., 1991; Leibbrandt et al., 2013).

Real World Parallels: the study investigated

communication in the USA (individualist culture) and

in Syria (collectivist culture), and reported that Syrian

respondents preferred strategies that were ritualistic,

indirect and cooperative, but American respondents

preferred strategies that were hostile, direct and

competitive (Merkin & Ramadan, 2010).

The Sub-Strategies: this strategy contributes to the

competitive strategy and the harmony strategy.

• The Competitive Strategy: A sense of

competition between members of a group could

be promoted with the competitive strategy.

Target Audience: Individuals in individualist

cultures.

• The Harmony Strategy: When the level of

cooperation between group members is

increased, a sense of harmony relationship is

promoted by the harmony strategy. Target

Audience: Individuals in collectivist cultures

7.2 Strategy 2: Identity

Description: The differences between collectivist

users and individualist users in the views about the

self are described by the strategy.

Antecedents: How individual people understand

themselves in relating to other people explains the

concept of the self, and Erez and Earley (1993)

suggest that people represent their social roles, social

identity and personality as the self. People in

individualist cultures often perceive themselves as

separate from the social context, and independently

follow their own projects and interests. People in

collectivist cultures often perceive themselves as

connected to social contexts with relationships with

other people that are interdependent (Markus and

Kitayama, 1991). Therefore, people living in

individualist cultures often perceive themselves as

unique (Shulruf et al., 2007; Triandis, 1994), but

people living in collectivist cultures tend to feel they

fit into or belong to society, and do not feel isolated

(Triandis 1994; Triandis 2001).

Real World Parallels: An example of parents in an

individualist culture, such as the USA, would

encourage their children when reluctant to eat the

meal prepared for them by telling them that children

in other countries have very little food, and that they

should be pleased that they are fortunate. An example

of parents in a collectivist culture, such as Japan,

would encourage their children when reluctant to eat

the meal prepared for them by telling them that the

farmer that had grown the rice had wasted his time,

so he would feel bad if the children did not eat the

rice, so they are encouraged to think more about the

producer of the food rather than themselves. The

example of the Japanese family suggests the

importance of interdependence with others and fitting

in and being concerned about others. The example of

the USA family suggests the importance of promoting

the self, noticing the differences with others and

focusing on the self (Markus and Kitayama, 1991).

The Sub-Strategies: this strategy contributes to

Individual-identity strategy and Group-identity

strategy.

• Individual-identity Strategy: This strategy aims

to promote uniqueness, independence, and an

independent view of self in cooperation. Target

Audience: Individuals in individualist cultures.

• Group-identity Strategy: This strategy aims to

promote belonging, fitting in and an

interdependent view of self in cooperation.

Target Audience: Individuals in collectivist

cultures.

7.3 Strategy 3: Assessment Norm

Description: The differences between collectivist

users and individualist users form the basis for the

strategy in terms of the perceptions of compensation

or rewards for an individual within a group.

Antecedents: The review of literature into reward

allocation preferences indicates cross cultural

differences, so that individuals from an individualist

culture tend to prefer equity based allocation of

rewards, but individuals from a collectivist culture

tend to prefer equality based allocation of rewards

(Triandis, 2001; Fadil et al., 2009). Therefore, values

of collectivist cultures emphasise affiliation and

cooperation, but values of individualist cultures

emphasise achievement and competition, so that

individualist values are more compatible with equity

norms and identify individual performance for career

progression and reward systems, as well as pay for

performance systems (Gelfand et al., 2007).

Real World Parallels: In a study that compared

distribution of rewards in a group and decision rules,

Japanese respondents described as collectivist and

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

62

Australian respondents described as individualist,

were involved in a game of decisions for classroom

administration. Australian respondents had a

tendency to follow self-interest rules in this game, and

Japanese respondents had a tendency to follow equal-

say rules (Mann et al., 1985).

The Sub-Strategies: this strategy contributes to

Equity strategy and Equality strategy:

• The Equity Strategy: The equity strategy

proposes that persons who allocate rewards or

compensation within a group distribute them in

proportion to each member’s contributions.

Target Audience: Individuals in individualist

cultures.

• The Equality Strategy: The equality strategy

proposes that persons who allocate rewards or

compensation within a group distribute them for

a group of users for the actions of an individual

user. Target Audience: Individuals in

collectivist cultures.

7.4 Strategy 4: Superordinate Goals

Description: The differences between collectivist

users and individualist users in goals, interests and

motivations described by the strategy.

Antecedents: In societies defined as having an

individualist culture, group interests are less

important than individual interests, so that individuals

in this type of culture are often motivated by potential

loss of self-respect and feelings of personal guilt, so

that they tend to be goal orientated and self-

motivated. This contrasts with societies defined as

having a collectivist culture, as individuals tend to

maintain traditions by being good members of groups

by adapting their virtues and skills, and in a

collectivist culture typical motivators are loss of face

and shame (Hofstede, 2001; Triandis, 2001; Triandis,

1994; Plueddemann, 2012).

Individuals often emphasise personal autonomy,

freedom of choice and personal responsibility as

values of personal independence in individualist

cultures, and often show a preference for the

independence of groups and self-directed behaviour,

as these individuals attempt to maintain personal

opinions and attitudes that are distinctive (Triandis

1994; Shulruf et al. 2007). In contrast, a sense of

working within a group, interdependence and duty to

a group are attitudes represented in a collectivist

culture, as values in these societies stress that

personal goals in groups are less important than

maintaining the goals of the group. Therefore,

individuals living in a collectivist society are

interdependent with their in-group, and there is a

collective responsibility for accountability and

sharing responsibility (Triandis 2001; Triandis 1994).

Real World Parallels: In Japan, managers of

organisations often use participative programmes,

employee suggestions and team decision-making or

delegate responsibilities to team members and

practice team working as a business strategy.

Therefore, Japanese managers tend to adopt

restrictive methods by expecting employees to obey

and honour all management decisions, but also adopt

relaxed methods by looking for consensus when

issues arise, even minor issues, and ask for

suggestions and ideas from employees (Sagie &

Aycan, 2003). Japanese organisations often introduce

activities, such as team names, team banners, team

dormitories and collective meals, to enhance

productivity, as these types of activities help to

integrate workers within their team and encourage

effective teams. This contrasts with patterns of group

working in Western countries, such as the USA, the

UK, Sweden, Canada and Australia, where work

teams are often self-managing, semi-autonomous or

autonomous, so that team working operates as a form

of self-management, and is widely applied in these

countries (Sagie & Aycan 2003). According to

Hofstede (2001), there is a perception that in the USA

and the UK, higher quality decisions are made by

individuals, when compared to decisions made by

groups.

The Sub-Strategies: this strategy contributes

independence goal strategy and interdependence goal

strategy.

• The Independence Goal Strategy: This strategy

aims to promote self-goal, self-interest, personal

responsibility and a sense of independence in

cooperation. Target Audience: Individuals in

individualist cultures.

• The Interdependence Gaol Strategy: This

strategy aims to promote group-goal, group-

interest, collective responsibility and a sense of

interdependence in cooperation. Target

Audience: Individuals in collectivist cultures.

8 PROTOTYPE DESIGN

A key motivation for this research was to establish

whether a culturally related group-based tool would

be more effective and more welcomed by a target

audience, than a tool that was assumed to be neutral.

This led to developing a prototype for testing whether

the system design strategies detailed in Section 5

Incorporating Cultural Factors into the Design of Technology to Support Teamwork in Higher Education

63

provided useful design directions. The design of the

prototype for teamwork was titled IdeasRoom.

8.1 The IdeasRoom Prototype

One of the most important strategies in developing

creative thinking is brainstorming, which is a skill

required by computer science students, since

designing and innovation is at the centre of computer

science (Shih, Venolia and Olson, 2011). IdeasRoom,

a medium-fidelity prototype, was used in this study to

simulate a web-based tool designed to support

students with group activity, which is designed to

encourage electronic group brainstorming for

students to generate ideas within their groups.

Prototype designs were carried out using Balsamiq,

providing a useful initial simulation. It was selected

because it resembles a medium-fidelity prototype. Its

use encourages users to view it as work in progress

rather than a completed product, thus encouraging

users to provide more feedback than they might for a

more ‘finished’ product. In addition, its

comprehensive layout offers high visual elements,

resulting in users feeling that they are using the real

environment. The evaluation focuses upon the

behaviour and needs of users, instead of the visual

elements. IdeasRoom is based on a discussion forum

format. There are five main options in IdeasRoom,

namely ‘add idea’, ‘idea comment’, ‘ideas list’,

‘visibility score of participation’ and a ‘leader board’.

8.2 Incorporating RING Strategies into

IdeasRoom

IdeasRoom was intended to be an experimental tool

by designing one version that would appeal more to

individualist users (which we refer to as the IND

version) and another that would appeal more to

collectivist users (which we refer to as the COL

version). While cultural identity is complex, the

cultural assumptions of the IND version of

IdeasRoom are based on typical attitudes of

individualists, while those of the COL version are

based on typical attitudes of collectivists. Our

intention was to make the IND and COL versions of

IdeasRoom able to equally promote group

brainstorming activity for different types of audience.

At this stage of the design, a student’s allocation to a

particular group is not yet carried out because of this

function has yet to be implemented. In the next stage

of the IdeasRoom design, adaption rules will be

developed to allocate students to specific groups.

These rules will be based on a match or mismatch of

each student’s pre-assessed cultural type (individual

or collectivist).

8.2.1 IdeasRoom IND Version

In the IND version, R.I.N.G. sub-strategies for

individualism culture are incorporated: competition

strategy, individual-identity strategy, equity strategy

and independent goal strategy.

To increase the feel of the competition, the leader-

board in the IND version was adapted. Members’

ranking in the leader-board is applied and ranked by

higher member contribution. Contribution is defined

by the total number of ideas and idea comments

generated by the member. It ranks the names of group

members and their contributions, which should

promote in-group competition strategy.

To promote Individual-identity strategy, self-

information is provided in many forms. Users are

identified by their name and personal greeting

message. Also, user pictures are used for personal

identity and to promote a feel of the uniqueness. In

the leader-board, the representation of information as

members instead of the group together with visibility

of user participation should increase the view of

independence.

The equity strategy is applied in representing

participation in the group as a member score.

Participation in the prototype by generating ideas will

increase the score of the member. Finally, the

independent goal strategy is also promoted. The

design increases the sense of the personal goal.

Participation is the main goal in IdeasRoom and in the

IND version, individual participation is promoted.

The design motivates users to work for their

independent goals, such as changing their position in

the leader-board by increasing their participation, and

to work to increase their own score of participation.

8.2.2 IdeasRoom COL Version

In the COL version, R.I.N.G. sub-strategies for

collectivism culture are incorporated: harmony

strategy, group-identity strategy, equality strategy

and interdependent goal strategy.

To increase the feel of collaboration and harmony,

the leader-board in the COL version is adapted. The

leader-board was adapted based on between-group

competition technique, which is suggested as a

technique that encourages in-group collaboration

(Cárdenas & Mantilla, 2015; Hausken, 2000). Group

ranking in the leader-board is applied and ranked by

higher group contribution. Contribution is defined by

the total number of ideas and idea comments

generated by all members in the group. It ranks the

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

64

names of groups and the group contributions, which

should promote in-group harmony strategy.

To promote Group-identity strategy, group

information is provided in many forms. Users are

identified by the group name and the greeting

message is personalised with the group name. Also, a

group picture is used as an identity, which promotes

a feeling of belonging to the group. In the leader-

board, the representation of information as groups

instead of members, together with visibility of shared

participation, should increase the view of

interdependence.

The equality strategy is applied in representing

participation in the group as a collective score. Any

member of the group can participate in the prototype

by generating ideas that should increase the score.

Finally, the interdependent goal strategy is also

promoted. The design increases the sense of the

shared goal. The design motivates users to work for

the interdependent goal, such as to change the group

position in the leader-board, each member in the

group could work to increase group participation and

it is necessary to work together to increase the

collective score.

9 CONCLUSIONS

This paper summarises the process of incorporating

cultural factors in the design of technology that

supports teamwork. Interviews with lecturers and

students who had experience with teamwork were

conducted that aimed to explore cultural factors in

group work activities. The analysis of the interviews

used thematic analysis that was accomplished in two

phases. The main focus in the first phase is

individualism theme and collectivism theme, while

the main focus in the second phase is the differences

between individualism and collectivism in teamwork.

This identified four key differences: In-Group

Relationships (R), Identity (I), Assessment Norms

(N) and Superordinate Goals (G).

R.I.N.G. design strategies were identified from

the cross-cultural psychology literature relating to the

bipolar dimension of individualism–collectivism, and

used with the responses from the interviews. The

design of the two versions of the prototype of the

system is called IdeasRoom. The IND version should

appeal more to individualist users and the COL

version should appeal more to collectivist users. The

discussion explained how the design was informed by

the R.I.N.G. design strategies in both versions.

Currently, the prototype is undergoing iterative

testing and development as a web-based system for

students, and there is a focus on the design and

usability issues that have emerged from the user tests

of the initial prototypes of IdeasRoom. An analysis of

the evaluation findings highlighted issues within the

IdeasRoom design that needed to be reconsidered and

adapted, which shaped how the final phase of

IdeasRoom development should be approached. Once

this is fully implemented, the system will be

evaluated by examining the effectiveness of the

system in terms of encouraging participation and its

ability to enhance students’ attitudes towards group

work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to all participants involved in this

research. This research is supported by Saudi Arabia

Cultural Bureau in London, UK, and Saudi Electronic

University in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

REFERENCES

Aronson, J., (1994), A Pragmatic View of Thematic

Analysis by Jodi Aronson, The Qualitative Report, 2,

pp.1–3.

Bishop, J.W., Chen, X. & Scott, K.D., (1999), What drives

Chinese toward teamwork? A study of US-invested

companies in China.

Cárdenas, J.C. & Mantilla, C., (2015), Between-group

competition, intra-group cooperation and relative

performance, Frontiers in behavioural neuroscience, 9.

Cox, T.H., Lobel, S.A. & McLeod, P.L., (1991), Effects Of

Ethnic Group Cultural Differences On Cooperative

And Competitive Behavior On A Group Task, Academy

of Management Journal, 34(4), pp.827–847.

Drury, H., Kay, J. & Losberg, W., 2003. Student

satisfaction with groupwork in undergraduate computer

science: do things get better? In Proceedings of the fifth

Australasian conference on Computing education-

Volume 20. Australian Computer Society, Inc., pp. 77–

85.

Erez, M. & Earley, P.C., (1993), Culture, self-identity and

work.

Evers, V., (2001), Cultural aspects of user interface

understanding: an empirical evaluation of an e-learning

website by international user groups.

Fadil, P.A., Williamson, S. & Knudstrup, M., (2009), A

theoretical perspective of the cultural influences of

individualism/collectivism, group membership, and

performance variation on allocation behaviors of

supervisors, Competitiveness Review: An International

Business Journal, 19(2), pp.134–150.

Galanes, G.J., Adams, K.H. & Brilhart, J.K., (2003),

Effective group discussion: Theory and practice,

McGraw-Hill Humanities Social.

Incorporating Cultural Factors into the Design of Technology to Support Teamwork in Higher Education

65

Gelfand, M.J., Erez, M. & Aycan, Z., (2007), Cross-cultural

organizational behaviour, Annual review of psychology,

58, pp.479–514.

Gibbs, G., (2009), The assessment of group work: lessons

from the literature, Assessment Standards Knowledge

Exchange.

Goo, A.B., (2011), Team-based Learning and Social

Loafing in Higher Education.

Hall, E.T., (1989), Beyond Culture, Anchor.

Hausken, K., (2000), Cooperation and between-group

competition, Journal of Economic Behavior &

Organization, 42(3), pp.417–425.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010).

Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (3rd

ed.): McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G.H., (2001), Culture’s consequences:

Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and

organizations across nations, Sage.

Hofstede, G.H., (1996), Cultures and Organizations,

Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and its

Importance for Survival.

Khaled, R., (2008), Culturally-Relevant Persuasive

Technology, Pt Design, p.256.

Kim, J.H., 2013. Information and culture: Cultural

differences in the perception and recall of information.

Library and Information Science Research, 35(3),

pp.241–250.

Leibbrandt, A., Gneezy, U. & List, J.A, (2013), Rise and

fall of competitiveness in individualistic and

collectivistic societies, Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,

110(23), pp.9305–8.

Mann, L., Radford, M. & Kanagawa, C., (1985), Cross-

cultural differences in children’s use of decision rules:

A comparison between Japan and Australia, Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 49(6), pp.1557–

1564.

Markus, H.R. & Kitayama, S., (1991), Culture and the self:

Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation,

Psychological Review, 98(2), pp.224–253.

Myers, S.A., Bogdan, L.M., Eidsness, M.A., Johnson, A.N.,

Schoo, M.E., Smith, N.A., Thompson, M.R. and

Zackery, B.A., 2009. Taking A Trait Approach To

Understanding College Students'perceptions Of Group

Work. College Student Journal, 43(3), p.822.

McSweeney, B., 2002. Hofstede’s Model of National

Cultural Differences and their Consequences: A

Triumph of Faith - a Failure of Analysis. Human

Relations, 55(1),

Merkin, R. & Ramadan, R., (2010), Facework in Syria and

the United States: A cross-cultural comparison,

International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34(6),

pp.661–669.

Mittelmeier, Jenna; Heliot, Y.; Rienties, B. and Whitelock,

D. (2015). The role culture and personality play in an

authentic online group learning experience. In:

Proceedings of the 22nd EDINEB Conference:

Critically Questioning Educational Innovation in

Economics and Business: Human Interaction in a

Virtualising World (Daly, P.; Reid, K.; Buckley, P. and

Reeve, S. eds.), 03-05 June 2015, Brighton, UK,

EDiNEB Association, pp. 139–149.

Plueddemann, J.E., (2012), Leading across cultures:

Effective ministry and mission in the global church,

Inter Varsity Press.

Powell, A., Piccoli, G. & Ives, B., (2004), Virtual Teams:

A Review of Current Literature and Directions for

Future Research, ACM SIGMIS Database, 35(1), pp.6–

36.

Sagie, A. & Aycan, Z., (2003), A Cross-Cultural Analysis

of Participative Decision-Making in Organizations,

Human Relations, 56(4), pp.453–473.

Shih, P.C. and Venolia, G. and Olson, G.M., (2011),

Brainstorming Under Constraints: Why Software

Developers Brainstorm in Groups, In Proceedings of

the 25th BCS Conference on Human-Computer

Interaction. pp. 74–83.

Shulruf, B., Hattie, J. & Dixon, R., (2007), Development of

a New Measurement Tool for Individualism and

Collectivism, Journal of Psychoeducational

Assessment, 25(4), pp.385–401.

Smith, C. & Bath, D., (2006), The role of the learning

community in the development of discipline knowledge

and generic graduate outcomes, Higher Education,

51(2), pp.259–286.

Smith, G.G. et al., (2011), Overcoming student resistance

to group work: Online versus face-to-face, Internet and

Higher Education, 14(2), pp.121–128.

Triandis, H.C., (1994), Culture and social behaviour,

McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Triandis, H.C., (1995), Individualism & collectivism,

Westview Press.

Triandis, H.C., (2001), Individualism-collectivism and

personality, Journal of personality, 69(6), pp.907–924.

Tutty, J.I. & Klein, J.D., (2008), Computer-mediated

instruction: A comparison of online and face-to-face

collaboration, Educational Technology Research and

Development, 56(2), pp.101–124.

Vöhringer-Kuhnt, T., (2002), The influence of culture on

usability, Department of Educational Sciences and

Psychology, Berlin, Germany: Freie Universität Berlin.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

66