Evaluating Lectures Through the Use of Mobile Devices

Auditorium Mobile Classroom Service (AMCS)

as a Means to Bring Evaluation to the Next Level

Felix Kapp

1

, Iris Braun

2

and Tenshi Hara

2

1

Chair of Learning and Instruction, Technische Universit

¨

at Dresden, Dresden, Germany

2

Chair of Computer Networks, Technische Universit

¨

at Dresden, Dresden, Germany

Keywords:

Mobile Devices, University Lecture, Teaching Evaluation, Formative Assessment.

Abstract:

For lecturers at universities timely feedback from their students is very important in order for them to improve

their teaching with adaptations targeted at the students’ requirements. Classical evaluation methods address

overall evaluations at the end of a semester, commonly with paper-based questionnaires. However, this does

not provide direct benefit to the students of that course as adaptations will most likely be carried over into

the next iteration of the same course. For this reason, students’ motivation to participate in these surveys

decreases over time. Therefore, we propose a tool support for continuous evaluation during the conduct

of a course available the whole semester, including direct feedback during the lecture, formative evaluation

during the entire course, and a summative evaluation at the end of the course or semester. For that purpose,

we expanded the functionality of the interactive Auditorium Mobile Classroom Service (AMCS), which was

developed to support students in self-regulated learning (SRL) processes during classical university lectures.

In the present article the concepts and features of AMCS for evaluation are described. Furthermore, we report

first experiences from a field test in two university lectures.

1 INTRODUCTION

Auditorium Mobile Classroom Service (AMCS) is a

project that aims at enhancing the quality of lectures

by providing support to the students and the lecturer.

It addresses problems like the lack of interactivity

in huge university classes and facilitates learning in

terms of an active, constructive and highly individual

process [Seel, 2003].

Based on didactical concepts such as peer instruc-

tion [Mazur, 1997] as well as the possibilities au-

dience response systems (ARS) offer [Mayer et al.,

2009, Weber and Becker, 2013], AMCS developed

certain features, which support students during uni-

versity lectures in mastering the demands of the learn-

ing process. In contrast to traditional ARS and click-

ers, AMCS is based on a psychological framework

describing the learning process of students during

the lecture. The different features are derived from

models of self-regulated learning (e.g. [Hadwin and

Winne, 2001,Zimmerman et al., 2000]). With AMCS

the lecturer is able to construct learning questions,

surveys and messages for distinctive students in ad-

vance of the lecture. These interventions are delivered

during the session according to defined rules. AMCS

thereby expands the role of the lecturer from a teacher

who stands in front of the audience presenting rele-

vant information towards a designer of a learning en-

vironment, which contains more than only the presen-

tation in the lecture hall. The AMCS app is used to de-

liver specific interventions to the students. The main

features of AMCS have been evaluated and constantly

developed (e.g., [Kapp et al., 2014,Hara et al., 2015]).

In the latest version we focused on a feature that ad-

dresses the needs of the teacher. In order to help stu-

dents in the auditorium to successfully learn, teachers

have to know more about the audience: their inter-

ests, their personal goals, the state of knowledge, their

difficulties and their motivation must be considered

when designing support. A continuous evaluation in

terms of formative evaluation during the course and a

summative evaluation at the end of the course is nec-

essary in order to improve the quality of the classes.

Therefore, the present contribution reports possibil-

ities to bring evaluation of university classes to the

next level via the tool AMCS. We first start with a

description of the main features of AMCS. We then

elaborate how AMCS can improve the evaluation and

Kapp, F., Braun, I. and Hara, T.

Evaluating Lectures Through the Use of Mobile Devices - Auditorium Mobile Classroom Service (AMCS) as a Means to Bring Evaluation to the Next Level.

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2016) - Volume 2, pages 251-257

ISBN: 978-989-758-179-3

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

251

in what contexts it can be used in order to improve the

quality of the lecture. In 4 we present findings from

two pilot studies before ending with a conclusion and

thoughts about further development.

2 FEATURES OF AMCS

The latest version of AMCS contains six features

which basically aim at supporting students in master-

ing the demands of the learning process. According to

[Zimmerman et al., 2000] students have to face vari-

ous demands during the forethought phase, the perfor-

mance phase and the self-reflection phase. Students

differ with regard to the goal orientation, attribu-

tion style and prior knowledge. Therefore, they plan

their learning differently (e.g., select specific learning

strategies) and process new information in distinctive

ways. The evaluation of the learning activity during

the self-reflection phase as well as the change of rele-

vant strategies for the next learning activity is also in-

fluenced by personal experiences. Whether or not stu-

dents identify a learning strategy as useless depends

for example on their metacognitive skills. The follow-

ing seven features aim at supporting students during

the forethought phase, the performance phase and the

self-reflection phase of the learning process.

2.1 Interests / Personal Goals

At the beginning of the lecture students are asked

about their personal goals and interests. Therefore,

their mobile device presents a few questions address-

ing for example whether they “are interested in the

topic or just need the credit points for the course”. An

example is shown in figure 1. The answers are stored

for each student in a database and are used as triggers

for possible later interventions such as messages and

learning questions. At the same time, the short sur-

vey at the beginning helps students to reflect on their

own goals and the lecturer to know more about the

composition and motivation of the audience.

2.2 Learning Questions during Lectures

AMCS is able to deliver learning questions at dif-

ferent points of time during the lecture. In contrast

to other ARS, AMCS provides individual feedback

(the students’ individual datasets also allow individ-

ualized feedback). Students can answer multiple-

choice questions on their smartphones and receive

feedback after choosing an option. After the sec-

ond incorrect attempt AMCS displays the correct an-

swer. The lecturers are still able to display the audi-

(a) survey (b) learning question

Figure 1: Exemplary survey and learning questions in stu-

dents’ view.

ence’s aggregated results on the presentation screen in

case they want to discuss them in public. Along with

AMCS comes a tutorial helping lecturers to design

learning questions and feedback according to certain

construction rules, making them powerful tools to

support the learning process both in the necessary

cognitive and metacognitive processes. An example

of a learning question is shown in 1.

2.3 Metacognitive Prompts

Depending on the students’ preference (e.g., exam

preparation or interest in the subject), which they in-

dicate in the survey at the beginning of the lecture,

strategic guidance is delivered during the lecture. If

students stated that their main goal in the present class

is to pass the exam, they might receive the following

message: “The issue on the current slide is relevant

for the exam. The professor may ask . . . ”. The in-

tention of metacognitive prompts is to help students

to regulate their attention and motivation in order to

reach their personal learning goals.

2.4 Cognitive Prompts

The learning questions at the beginning, in the middle

and at the end of the lecture contain the possibility

to identify students’ knowledge gaps. Thus, students

who have made mistakes in a learning question at the

beginning of the lecture, may receive the following

exemplary message containing a cognitive prompt at

a later point of time: “You have made a mistake in the

first learning question at the beginning. The correct

answer is discussed by Prof. Y on the current slide.”

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

252

2.5 Providing Further Material and

Initiating Discussions

AMCS allows sending additional information to the

students, such as links, documents, and presentation

slides. This happens according to their personal learn-

ing goals. Furthermore the lecturer has the possibil-

ity to induce and enhance slow discussions by send-

ing personalized messages like “Stand up right now

and ask the following question loudly into the room:

‘What is the practical use of this theory?’”. By doing

so students can be animated to pose questions which

allow them to reach the next knowledge level.

2.6 Facilitating an Immediate and

Substantial Evaluation

AMCS offers the possibility to evaluate university

lectures on a new level. Compared to traditional ways

of evaluation, it allows to collect more information

by the means described earlier in this section. Pro-

viding learning questions, surveys with different for-

mats, and messages allows gathering data relevant for

evaluation. Besides, AMCS also has an extra function

for immediate feedback to the lecturer. Students can

indicate whether they want the lecturer to in- or de-

crease the volume, or whether they want to proceed to

the next topic or remain on the current slide for some

more time. An interface for the immediate feedback

is displayed in the lower areas of subfigures 1(a) and

1(b). – This last feature is described in more detail in

the next section.

3 BRINGING EVALUATION OF

LECTURES TO THE NEXT

LEVEL

Evaluation is often realized with questionnaires at the

end of trimesters or semesters. Students are asked to

answer a set of items, which asked for their judgement

of the lecture. The data assessed with these ques-

tionnaires are subjective ratings for about 14-16 ses-

sions. If distributed via paper-pencil questionnaires

the data analysis takes some more time. Therefore, a

discussion about the results of the evaluation is often

not realized, results are delivered after the course fin-

ished. Furthermore, the summative character of the

evaluation makes it difficult to actually provide sub-

stantial information for the lecturer about how to im-

prove. Questions like “Did the teacher seem to be

prepared for the class?” asked students to rate a char-

acteristic that may vary from week to week. An over-

all rating at the end of a course indicating the need

to improve in that point is useless for the students of

the current course and does not provide the lecturer

with useful information on how to enhance the quality

or to dispose this impression. With that background,

AMCS intends to improve lecture evaluation by pro-

viding information which are available over longer

time periods as well as immediately during and af-

ter single lectures. Furthermore, AMCS improves the

quality of evaluation by providing more valid infor-

mation through the use of various data sources. The

functionalities AMCS offers for evaluation can be cat-

egorized by A) the point of time, the evaluation takes

place, and B) the type of data that is used. In the fol-

lowing chapter these two dimensions are described.

3.1 Point of Time

In contrast to the conventional evaluation of courses

at the end of a semester, the evaluation with AMCS

allows formative evaluation during the lecture and af-

ter single lectures as well as a summative evaluation

at the end of a whole course.

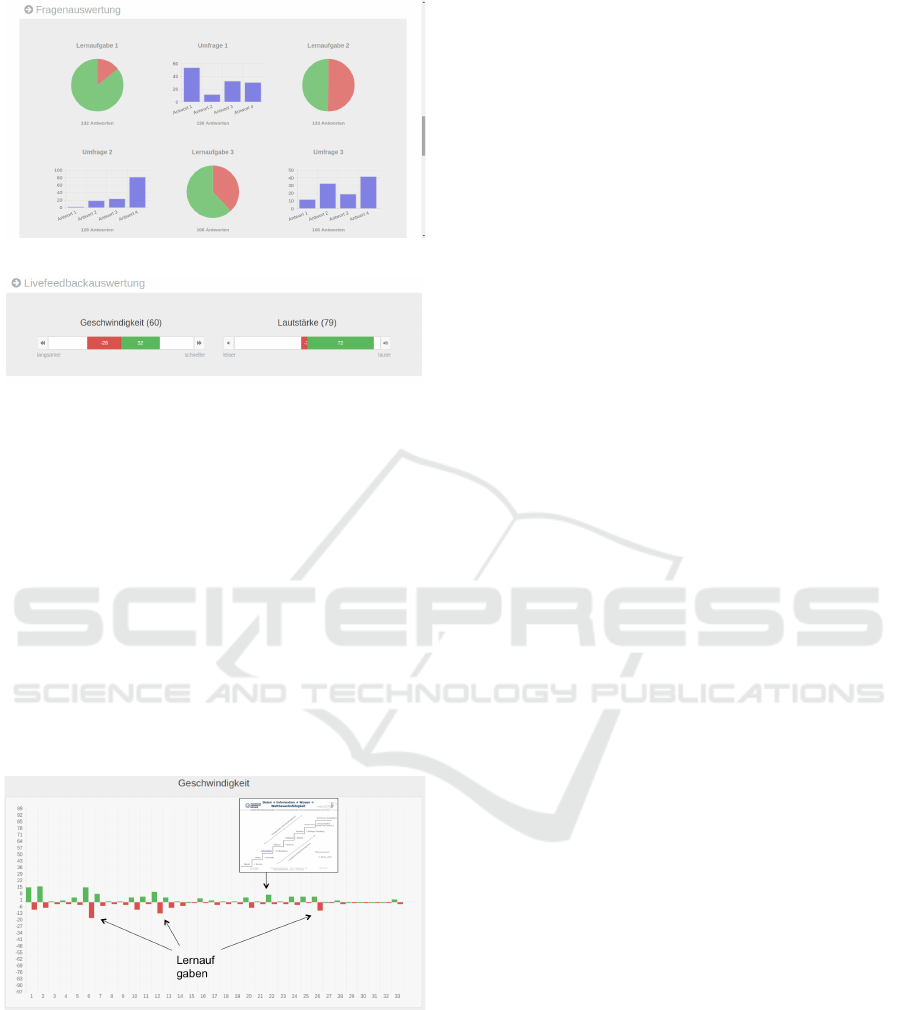

3.1.1 During the Lecture

Lecturers can use some information to improve their

presentation during the session. As they are normally

busy with explaining content to the audience the inter-

face which presents any kind of evaluation informa-

tion should only contain the most necessary informa-

tion and do not interrupt the lecture. AMCS presents

results of the live-feedback (volume and speed) and

displays the learning question results of the students

(as shown in 2). Especially within the breaks in which

students work on learning questions (see 2.2) the lec-

turer can check how much students did understand

the current topic (by having a look at the learning

question results). For the instant feedback we are

currently developing a smartwatch application which

feeds back the most important information in ”real-

time” to the wrist of the teacher.

3.1.2 After Single Lecture

Detailed analysis of learning questions, surveys and

live-feedback about the speed and volume allows the

lecturers to get a valid idea what just happened in the

lecture hall. By considering all used learning ques-

tions (as shown in 2), one could discover what the

audience did understand and what should appear at

the beginning of the next session when it comes to

recapitulation of important concepts. By asking cer-

tain questions via the survey tool students can artic-

ulate concerns, wishes or questions. Furthermore, a

Evaluating Lectures Through the Use of Mobile Devices - Auditorium Mobile Classroom Service (AMCS) as a Means to Bring Evaluation

to the Next Level

253

(a) results of learning questions

(b) evaluation of instant feedback

Figure 2: Results of learning questions (upper subfigure)

and instant feedback (lower subfigure).

combination of data facilitates a deeper insight into

the knowledge states of the audience. If the lecturer

asked at the beginning of the class what interests the

students have and what career they are studying, it is

possible to analyze the data for each sub-population

and identify needs of groups of people. An aggre-

gated presentation of live-feedback data allows identi-

fying critical moments or content within one session.

In 3 the speed ratings over one 90-minute session with

33 presentation slides are shown. That way the lec-

turer can reflect on parts where the audience seems to

have experienced difficulties.

Figure 3: Aggregation of live-feedback ratings for one 90-

minute session.

3.1.3 After Course/Trimester/Semester

AMCS is able to realize the traditional evaluation sur-

veys at the end of a whole course. The supported

formats contain scale questions, questions with a free

text field, multiple and single choice questions. As

the database stores answers for every user over the

time of the whole course, analysis can reveal learning

progress by taking a look at the learning questions.

As AMCS can be used by simply registering a

pseudonym and a password, the evaluative feedback

can be considered equally as safe as a traditional pa-

per&pencil evaluation from the privacy perspective.

Privacy concerns remain on the usual and commonly

agreed upon as acceptable level of non-attributable

identifiers such as IP address or user agent string.

3.2 Type of Data

AMCS allows lecturers to assess different kind of data

in order to understand what happened in their class.

To demonstrate the evaluation possibilities of AMCS

these different methods are described in the following

section.

3.2.1 Surveys

The traditional surveys, which are often used for eval-

uation, can be distributed with AMCS. The lecturer

can design questions (single-choice, multiple-choice,

free text, scale) in advance of the session and define at

what point these questions are displayed on the mo-

bile devices of the students. Thus, it is possible to

assess subjective ratings of learning progress, satis-

faction with the teacher and the progress in class or

judgments about the circumstances (see 4).

3.2.2 Achievement Data

The results of the learning questions represent valid

data about the knowledge state for each student who

participated. The lecturer should have in mind, that

the learning questions might have to be designed with

another purpose than achievement assessment. For in-

stance, learning questions at the beginning of a lec-

ture might serve as hints for the upcoming class they

might indicate what concepts are relevant and im-

portant and thereby guide the learners’ attention. In

that case, the learning question would ask for con-

tent, which has not been taught, yet. The chances of

solving the learning question successfully in the first

attempt should be relatively low. Thus, the lecturer

should not take this result as an indicator for learn-

ing achievement. Still, learning questions at the end

of the class or at the beginning of the next session

addressing content, which has been taught, can serve

as diagnose tool to assess the knowledge of the au-

dience. Thereby, they supplement self-judgments of

learning achievement and progress of the surveys and

add an evaluation dimension, which is extremely use-

ful for teachers. Over- and underestimation of own

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

254

knowledge and skills is a common problem amongst

students.

3.2.3 Live-feedback and Utilization Data

Live-feedback data and log-files indicating how often

students worked on learning questions or participated

online in questionnaires etc. can be used to trace dif-

ficult parts or sessions over the semester. As shown

in 3.1.2 and 3 the live-feedback can help in identify-

ing content, which is perceived as difficult. Statistics

about the number of students who have been online

during the session and who worked on the learning

question reveal interesting data about the participation

over the semester.

4 PILOT-TESTS

The evaluation features were tested in two different

courses, 1) a computer science lecture, and 2) an “in-

troduction to economics”. In the first test, AMCS

was used for three 90-minute lecture sessions in a

row. The professor used several learning questions

and asked the students to evaluate the lecture at the

end. Over the three sessions 140 user accounts were

registered. As the registration did not have any re-

strictions some users created multiple accounts. In

case they forgot their login, they just created new ones

in the next session. Hence, the amount of created

accounts does not represent the number of students

who actually participated. However, we always had

between 45 and 55 answers for the questions, so we

can estimate that there were around 50 active users

per lecture. In the second test, two 90-minute ses-

sions gave the professor opportunity to utilize learn-

ing questions, survey questions and live-feedback. In

the first session 186 users were registered, in the sec-

ond 139.

In both courses students were introduced to

AMCS at the beginning of the first session. It was

explained that AMCS aims at supporting their learn-

ing process in the lecture, that the participation is vol-

untary and that the prototype and the project is still

under construction. In test scenario one we aimed at

evaluating the potential of surveys and learning ques-

tions, in test two the focus was on the live-feedback

data and learning questions.

4.1 Results of Pilot-test One

Scenario one addressed the potential of learning ques-

tions and surveys for the evaluation. In the first ses-

sion students were asked about their career and their

motivation/personal goal in the lecture. 28 students

answered: 20 studied computer science, 5 economics,

two studied non specified other careers and one edu-

cation. Nine students stated that they were interested

in the topic of the lecture (“because they are using

video- and streaming services. . . ”). Twenty-three in-

dicated that their motivation to visit the lecture is to

pass the exam at the end of the semester. Two were

interested in writing a bachelor or master-thesis about

the topic of the lecture, and five expected the lecture

to be valuable for their work as systems developer or

programmer.

Figure 4: Survey in pilot test in computer science lecture.

(a) “The selected topics about mobile computing were suit-

able as starting point for beginners.” (b) “I would recom-

mend using AMCS to other students.” (c) “The learning

questions during lecture were very helpful.” (d) “The sur-

veys during lecture were very useful.”

The information about the different interests and

personal goals of the students could be used for a

differentiated analysis of the evaluation and learning

questions. For example, the lecturer could filter the

results depending on the field of study and could de-

termine if students from a special field have more

problems than the others. The professor as well as the

students rated the learning questions as a useful tool

to identify problems and knowledge gaps. At the end

of the third lecture the students were asked about their

opinion about the selection of the topics in the lectures

as well as about the helpfulness of using AMCS espe-

cially learning questions and surveys in the lectures.

Their feedback were predominately positive.

4.2 Results of Pilot-test Two

Scenario two addressed the potential of learning ques-

tions and live-feedback data. Within this pilot-study

Evaluating Lectures Through the Use of Mobile Devices - Auditorium Mobile Classroom Service (AMCS) as a Means to Bring Evaluation

to the Next Level

255

the students could judge during the whole 90-minute

session whenever they had the feeling that the pro-

fessor was going too fast or too slow, or the volume

was not adequate. The data suggested that the live-

feedback is a tool that is used only in case of prob-

lems. In the two sessions of the economy course stu-

dents used the possibility to give feedback regarding

the volume only three times: At the beginning of the

first lecture, during the first lecture when the professor

was showing a video with poor sound quality and at

the beginning of the second lecture. At each of these

three points around 20% of the students judges the

volume as to low. Concerning the speed of the pro-

fessor there was only in the first session a significant

feedback activity (with more than 5% of the registered

and active students voting). Students used the speed

buttons to feed back to the professor if they need

more time to work on the learning questions. The

professor had prepared six learning questions, which

were distributed in blocks of two questions. Around

20% of the students voted during this breaks that they

want the professor to go on faster (if they had already

finished working on the learning questions) or to go

slower (if they need some more time). The evaluation

activity diminished in the second session. One expla-

nation is that students noticed that the professor was

not immediately changing his teaching. That points

out that there is the need of an interface which gives

relevant information back to the lecturer (see section

further development).

According to the professor, the results of the learn-

ing questions gave him a useful overview about the

knowledge state of his audience. Students appreci-

ated the possibility to work on learning questions as

well. They even judged them to be more useful than

the live-feedback tool.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER

DEVELOPMENT

AMCS provides opportunities to support students to

evaluate the lecturer and their teaching. The presented

features mainly aim at fostering regulation and mas-

tering demands of self-regulating learning of the stu-

dents. But they also can be used for the formative

evaluation during and after the lecture. The lecturers

can receive instant feedback – i.e., information in real-

time during each lecture – they can react to directly

during a lecture, e.g. by adapting their presentation,

but they can also receive evaluative feedback – i.e., a

summary of comments and opinion after the conclu-

sion of each lecture – in order to make some changes

after the course or semester have ended. The first pi-

lot tests have shown that learning questions, cognitive

and metacognitive prompts, and instant feedback can

be used in university lectures in order to support stu-

dents in mastering the demands of this learning situa-

tion as well as lecturers to improve their teaching. At

the end of the semester lecturers will be provided with

an overview of all events, allowing an overall evalua-

tion of the entire lecture or tutorial series.

In the next development steps we will focus on

the representation of the evaluation data to the lec-

turer. We will provide more features for the aggre-

gation and visualization of the evaluation results. In

order to provide the real-time feedback without too

much interruption of the presentation, a second de-

vice – i.e., a second screen – would be helpful; also, a

smartwatch could be utilized.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank our busily working team for im-

plementing the prototypes and providing valued con-

tributions to our concept, namely Patrick Buchholz,

Markus Heider, Tommy Kubica and Martin Weiss-

bach.

REFERENCES

Braun, I., Kapp, F., K

¨

orndle, H. and Schill, A. (2015). On-

linegest

¨

utzte Audience Response Systeme: F

¨

orderung

der kognitiven Aktivierung in Vorlesungen und Er

¨

off-

nung neuer Evaluationsperspektiven. In Proceedings

of the Wissensgemeinschaften in Wirtschaft und Wis-

senschaft 2015, 153–165.

Dubrau, M. and Krause, J. (2015). Mobiles Feedback

- Praxisbericht zur Integration eines Audience Re-

sponse Systems in eine Lehrveranstaltung als Instru-

ment der Lehrevaluation. Proceedings of the Wissens-

gemeinschaften in Wirtschaft und Wissenschaft 2015,

167–171.

Hadwin, A. F. and Winne, P. H. (2001). Conotes2: A soft-

ware tool for promoting self-regulation. Educational

Research and Evaluation, 7(2-3):313–334.

Hara, T., Kapp, F., Braun, I., and Schill, A. (2015). Compar-

ing tool-supported lecture readings and exercise tuto-

rials in classic university settings. In Proceedings of

the 7th International Conference on Computer Sup-

ported Education (CSEDU 2015), pages 244–252.

Kapp, F., Braun, I., K

¨

orndle, H., and Schill, A. (2014).

Metacognitive Support in University Lectures Pro-

vided via Mobile Devices. In INSTICC; Proceedings

of CSEDU 2014.

Kapp, F., Narciss, S., K

¨

orndle, H., and Proske, A. (2011).

Interaktive Lernaufgaben als Erfolgsfaktor f

¨

ur E-

Learning. Zeitschrift f

¨

ur E-Learning, 1(6):21–32.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

256

Mayer, R. E., Stull, A., DeLeeuw, K., Almeroth, K., Bim-

ber, B., Chun, D., Bulger, M., Campbell, J., Knight,

A., and Zhang, H. (2009). Clickers in college class-

rooms: Fostering learning with questioning methods

in large lecture classes. Contemporary Educational

Psychology, 34(1):51–57.

Mazur, E. (1997). Peer Instruction: A User’s Manual. Pren-

tice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, series in educa-

tional innovation edition.

Seel, N. M. (2003). Psychologie des Lernens: Lehrbuch

f

¨

ur P

¨

adagogen und Psychologen, volume 8198. UTB,

M

¨

unchen, 2. Auflage edition.

Weber, K. and Becker, B. (2013). Formative Evaluation

des mobilen Classroom-Response-Systems SMILE.

E-Learning zwischen Vision und Alltag (GMW2013

eLearning).

Zimmerman, B. J., Boekarts, M., Pintrich, P., and Zeidner,

M. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: a social cogni-

tive perspective. Handbook of self-regulation, 13–39.

Evaluating Lectures Through the Use of Mobile Devices - Auditorium Mobile Classroom Service (AMCS) as a Means to Bring Evaluation

to the Next Level

257