Supporting Zoo Visitors’ Scientific Observations with a Mobile Guide

Yui Tanaka

1

, Ryohei Egusa

1,2

, Etsuji Yamaguchi

1

, Shigenori Inagaki

1

, Fusako Kusunoki

3

,

Hideto Okuyama

4

and Tomoyuki Nogami

1

1

Kobe University, Hyogo, Japan

2

Research Fellow of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Tokyo, Japan

3

Tama Art University, Tokyo, Japan

4

Asahikawa City Asahiyama Zoo, Hokkaido, Japan

Keywords: Mobile Systems, Zoo, Science Learning.

Abstract: This study proposes an observation guide to support zoo visitors’ scientific observation of animals in motion

by providing viewpoints through animations. One of the difficulties that visitors experience when observing

animals is that they do not sufficiently understand the functions and behavior of the body parts of the animal

they are seeing. The guide aims to enhance visitors’ understanding by resolving this issue through the use of

animations of the functions and behaviors of parts of animals’ bodies. To evaluate the guide, we had

kindergarteners and elementary school students use its contents on seals while observing their hind flippers,

noses, and claws at the Asahiyama Zoo. Our finding was that the guide was an effective means to enhance

the children’s understanding of the functions and behaviors of these parts of the body.

1 INTRODUCTION

Zoos serve as places for science education (Bell et

al., 2009), as they allow children to observe the

natural movement of animals directly and learn

about the living environments and forms of animals

through observation (Dierking et al., 2002).

However, most children come to the zoo with their

families for leisure, so they often do not seem to

engage in focused observation of the living

environments and forms of animals at the zoo

(Patrick and Tunnicliffe, 2013), suggesting that they

require educational support in this setting.

In a comment on observation among children,

Eberbach and Crowley (2009) explained that

scientific observation is a complex practice that

requires the coordination of disciplinary knowledge

of, for example, the living environments and forms of

animals, and that children, with educational support,

are capable of making a transition from everyday

observations that focus only on obvious

characteristics to scientific observations. Furthermore,

they also noted that, during the shift between

everyday observations and scientific observations,

transitional observations take place that enable

children to connect features to functions and behavior.

Previous studies have utilized mobile devices to

enrich science education outside the classroom

through learning from observation by effectively

creating personalized learning environments (Traxler,

2005). Ohashi et al. (2008) developed a navigation

system that offered audio and video guidance with an

iPod. Furthermore, Jimenez Pazmino et al. (2013)

designed technological supports for docents running

an immersive, embodied-interaction with portable

tablets and large fixed displays.

Following up on these studies, we developed a

system to support observation among children to

help them move to “transitional noticing,” as

Eberbach and Crowley (2009) explained in their

study, which connects features to function and

behavior. This system provides viewpoints for

observation through animations that simulate

animals’ actual movements. We believe that these

animations provide a more focused approach to

observation so that children can easily understand

functions and behaviors, which is something that

still images alone were not able to do in the past.

This study proposes an observation guide that

supports the observation of the function and

behavior of each part of the body of an animal in

motion. The purpose of this study was to ascertain

whether the guide we developed, using content on

seals, was effective in providing viewpoints on the

Tanaka, Y., Egusa, R., Yamaguchi, E., Inagaki, S., Kusunoki, F., Okuyama, H. and Nogami, T.

Supporting Zoo Visitors’ Scientific Observations with a Mobile Guide.

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2016) - Volume 2, pages 353-358

ISBN: 978-989-758-179-3

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

353

function and behavior of the parts of the body.

2 SYSTEM OVERVIEW

2.1 Development Environment

HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and PHP5.3 were used to

create the development environment of the server.

The guide is Internet-based.

2.2 Flow of the Observation Guide

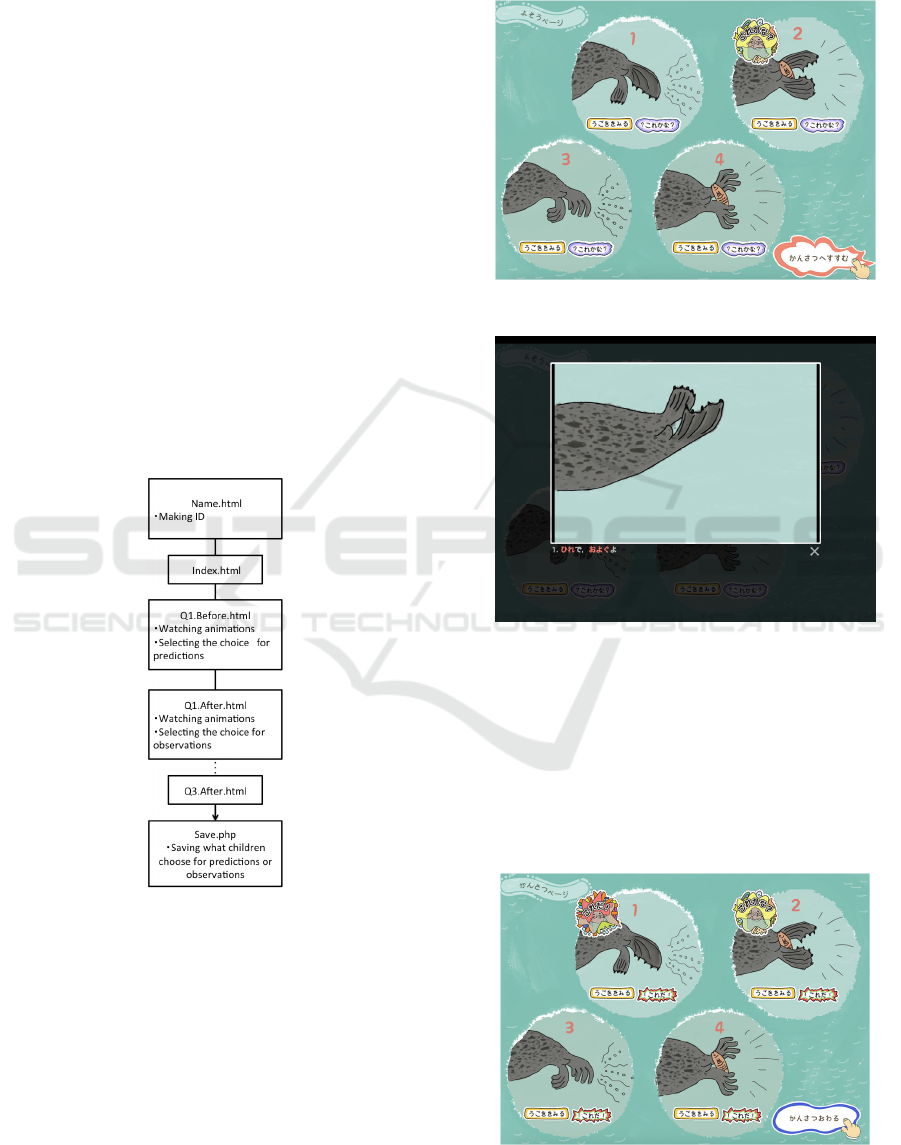

Figure 1 is a flowchart indicating the flow of the

guide. The first page is for entering the child’s name,

and is followed by the homepage.

A prediction page (before) and a result page

(after) are linked to each observation item. The child

selects one of the animated choices given by these

pages for each question related to the observation.

The choices that he/she has made before and after

the observation are then saved as a text file after the

last observation page.

Figure 1: Flow of observation guide.

2.3 Pages

2.3.1 Prediction Page (before)

Figure 2 shows a prediction page, which gives four

choices related to each observation item. Two buttons,

“Watch Animation” and “Prediction,” are displayed.

When the child presses the “Watch Animation”

button, the animation for each choice is activated.

Figure 3 shows an example of an animation page for

an observation item. The child can only select one

choice among the predictions. Once the choice is

made, the guide will move on to the observation page.

Figure 2: Prediction page.

Figure 3: Example of an animation page.

2.3.2 Result Page (after)

Figure 4 shows a result page. Here, the child is also

given four choices, with the choice he/she made

during the prediction phase indicated by the “My

Prediction” graphic. On this page, two buttons,

“Watch Animation” and “Result,” are displayed.

Similar to the prediction page, when the child

Figure 4: Result page/choices for hind flippers.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

354

presses the “Watch Animation” button, the

animation for each choice is activated. When the

child presses the “Result” button, the choice after the

observation is confirmed and the guide will move on

to the next observation item.

3 RESEARCH METHOD AND

DESIGN

3.1 Overview

The aim of this exercise was to facilitate observation

of the features of seals while also examining their

functions and behaviors. More specifically, the

children were to observe the features and behaviors

of seals’ hind flippers, noses, and claws. There were

four choices for each observation item. Figure 4

shows the choices for the hind flippers: 1.

Swimming using hind flippers; 2. Catching

something with hind flippers; 3. Swimming using

fingers; and 4. Catching something with fingers.

Figure 5 shows the choices for the nose: 1. Seals

always open their noses and breathe above water; 2.

Seals always open their noses and spray water on the

water surface; 3. Seals close their noses underwater

and open them to breathe above water; and 4. Seals

close their noses underwater and open them to spray

water on the water surface. Finally, Figure 6 shows

the choices for the claws: 1. Walking with fore

flippers without using claws; 2. Eating with fore

flippers without using claws; 3. Walking with fore

flippers using sharp claws; and 4. Eating with fore

flippers using sharp claws.

Observation was carried out in the following

steps. First, as shown in Figure 7, the children were

presented with the questions and choices using

images and the guide. They were then asked to

predict the right answers from among the choices as

shown in Figure 8. Finally, the children were asked

to observe the behavior of the seals in the exhibit

while using the guide and to select the answers from

among the choices once again (Figure 9). After these

steps, the right answers based on the observation

were revealed and explained. The above steps were

followed for each observation item, requiring

approximately 15 minutes each time. After they had

completed the observation of all the items, namely

the hind flippers, nose, and claws, the children were

interviewed for approximately 30 minutes (Figure

10).

Figure 5: Choices for nose.

Figure 6: Choices for claws.

Figure 7: Staff members showing questions to the

children.

Figure 8: A child watching an animation.

Supporting Zoo Visitors’ Scientific Observations with a Mobile Guide

355

Figure 9: A child using his tablet during observation.

Figure 10: A child being interviewed.

3.2 Participants

The participants were 16 children chosen from the

public; their mean age was 7.0 years (SD=2.0). One

or two adults accompanied each child during the

observation of the seals, and each child received a

tablet to use for this exercise.

3.3 Zoo

The Asahiyama Zoo where this study was conducted

is a pioneer in animal behavior exhibits and ranks

high in the number of visitors among zoos around

the world (Kosuge, 2006).

3.4 Data Source and Analysis

During this workshop, the verbal and non-verbal

communication and behavior of the children were

recorded using IC recorders and video cameras. For

analysis, we used the interview research method to

determine the children’s assessments of the

animations used during the observation of the hind

flippers, nose, and claws, and, more specifically,

whether the animations were useful and why.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Overall Trend

Table 1 shows the number of children who answered

whether the animations were useful or not useful.

Sixteen children stated that the animations for the

hind flippers as well as the nose were useful. Fifteen

children stated that the animations of the claws were

useful while one stated that they were not.

Table 1: Number of children who answered whether these

animations were useful.

Useful Not useful

Hind flippers 16 0

Nose 16 0

Claws 15 1

Note: N=16

4.2 Episodes

There are four episodes of the interview-based

research. Episodes 1 and 2 show the children’s

statements about the usefulness of the animations on

the Mobile Guide. Episode 3 shows a child’s

statement about the uselessness of one of the

animations. Episode 4 shows a child’s statement

about the improvement of the animation.

4.2.1 Episode 1: Interview of B11 about

Hind Flippers' Animation

Table 2 shows the episode with a five-year-old boy

(B11). He says the animations of hind flippers are

useful. He gives the reason, “When I forgot what I

Table 2: Episode 1: Interview of B11 about hind flippers'

animation.

01I11v: Was the animation of hind flippers useful for

observation?

02B11n: Nodding.

03I11v: Why?

04B11v: When I forgot what I had observed, I could

confirm it with the tablet immediately.

05I11v: When you confirmed it, did you need the

animation or just this still result page?

06B11v: I could do it just by the result page.

07I11v: How about the animation? Do you think the

animation was not needed?

08B11v: I needed the animation. As the picture on the

result page did not move, I could not understand how

the seals use their hind flippers.

Note on transcription numbers: Consecutive numbers, B11: a

5-year-old boy

,

I11: an interviewer

,

v: verbal behavior, n:

non-verbal behavior.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

356

had observed, I could confirm it with the tablet

immediately” (04B11v). To clarify the advantages of

the animation, Interviewer 11 asks, “When you

confirmed it, did you need the animation or just this

still result page?” (05I11v). The child answers, “I

needed the animation. As the picture on the result

page did not move, I could not understand how seals

use their hind flippers” (08B11v). Therefore, by

using the animation, B11 can confirm how seals use

their hind flippers.

4.2.2 Episode 2: Interview of G2 about the

Nose's Animation

Table 3 shows the episode with a six-year-old girl

(G2). She says the animation of the nose is useful,

“Because I could understand how seals move”

(04G2v). Interviewer 2 asks, “When you observed

the seals, did you check the same motion?” (05I2v).

She answers, “Yes” (06G2v). Therefore, G2 gets the

viewpoint for observation of nose’s function and

behavior from the animation. Further, she can

observe them.

Table 3: Episode 2: Interview of G2 about the nose's

animation.

01I2v: Was the animation of nose useful for observation?

02G2v: It was useful.

03I2v: Why?

04G2v: Because I could understand how seals

move.

05I2v: When you observed the seals, did you check the

same motion?

06G2v: Yes.

Note on transcription numbers: Consecutive numbers

,

G2: a 6-year-old girl

,

I2: an interviewer

,

v: verbal

behavior.

4.2.3 Episode 3: Interview of B1 about the

Nose's and Claws' Animation

Table 4 shows the episode with a seven-year-old boy

(B1). He says the animation of the nose is useful, but

the animation of the claws is not useful. B1 explains

that the animation of the nose is needed, “Because,

for example, the air, then you can’t see the air”

(04B1v). However, he says the animation of claws is

not needed, “Because, seal, seal, can eat, ah, you can

see the food and the hunt” (08B1v).

Therefore, B1 thinks that the animation of the

nose is useful because in the animation he can notice

the air, which we cannot see otherwise. He can

understand and observe how seals breathe on the

water. On the other hand, he thinks that the

animation of the claws is not useful because he can

see the food and the hunt. This shows that the

animation of the claws is not as useful for him as

that of the nose.

Table 4: Episode 3: Interview of B1 about the nose's and

claws' animation.

01I1v: Was the animation of nose needed or not?

02B1v: Needed.

03I1v: Why?

04B1v: Because, for example, the air, then you can’t

see the air.

…

05I1v: Was this animation needed or not?

06B1v: No need.

07I1v: Why?

08B1v: Because, seal, seal, can eat, ah, you can see the

food and the hunt.

Note on transcription numbers: Consecutive numbers

,

B1: a 7-year-old boy

,

I1: an interviewer

,

v: verbal

behavior.

4.2.4 Episode 4: Interview of G12 about the

Nose's Animation

Table 5 shows the episode with an eleven-year-old

girl (G12). She says that the animation of the nose

should be improved. She explains, “For beginners, it

looks misleading. In fact, seals open and close their

noses when they are on the water” (02G12v).

Interviewer 12 asks, “You think the animation is

good but it should be improved, right?” (07I12v).

She answers, “Yes” (08G12v). Therefore, G12 says

that the animation is useful but it should be

improved to represent the viewpoint of the nose’s

function and behavior more realistically.

Table 5: Episode 4: Interview of G12 about the nose's

animation.

01I12v: Was the animation of nose useful for

observation?

02G1v: For beginners, it seems misleading. In fact,

seals open and close their nose when on the water.

03I12v: Seals also open and close their nose, so you

think the animation should be improved, right?

04I12v: But, do you think this animation can show that

seals close their nose under the water and open it on the

water?

05G12v: Yes.

06I12v: You think the animation is good but it should

be improved, right?

07G12v: Yes.

Note on transcription numbers: Consecutive numbers

,

G12: an 11-year-old girl

,

I12: an interviewer

,

v:

verbal behavior.

Supporting Zoo Visitors’ Scientific Observations with a Mobile Guide

357

5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORKS

This study aimed to develop and assess an

observation guide. We discovered that the vast

majority of the children found this system useful

during the observation and that the system helped

the children understand the movements of the animal

sufficiently to engage in prediction and observation.

Our conclusion, therefore, is that this system was an

effective tool for observing the functions and

behaviors of parts of an animal’s body. To identify

the evidence that the system actually supports

children’s observation, we will examine how the

children use the system by video research for future

works.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI

Grant Number 24240100 and 15K12382.

REFERENCES

Bell, P., Lewenstein, B., Shouse, A. W., & Feder, M. A.

(Eds.), 2009. Learning science in informal

environments: People, place, and pursuit. National

Academies Press. Washington, DC.

Dierking, L. D., Burtnyk, K., Buchner, K. S., & Falk, J. H.,

2002. Visitor learning in zoos and aquariums: A

literature review. American Zoo and Aquarium

Association. Annapolis, MD.

Eberbach, C., & Crowley, K., 2005. From everyday to

scientific observation: How children learn to observe the

biologist's world, Review of Educational Research,

79(1), 39–68.

Jimenez Pazmino, P. F., Lopez Silva, B., Slattery, B., &

Lyons, L, 2013. Teachable mo[bil]ment: Capitalizing on

teachable moments with mobile technology in zoos. CHI

’13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, ACM, 643–648.

http://doi.org/10.1145/2468356.2468470.

Kosuge, M., 2006. The revolution of the Asahiyama zoo:

Revival project of a dream come true (in Japanese).

Kakukawashoten. Tokyo.

Ohashi, Y., Ogawa, H., & Arisawa, M., 2008. Making

new learning environment in zoo by adopting mobile

devices. Proceedings of the 10th International

Conference on Human Computer Interaction with

Mobile Devices and Services, ACM, 489–490.

http://doi.org/10.1145/1409240.1409323.

Patrick, P. G., & Tunnicliffe, S. D., 2013. Zoo talk. Ne

Springer. Netherlands.

Traxler, J., 2005. Defining mobile learning. In P. Isaias, C.

Borg, & P. Bonanno (Eds.), IADIS International

Conference Mobile Learning 2005, 261-266. Lisbon,

Portugal: IADIS Press.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

358