Constructivist Learning and Mantle of the Expert Pedagogy

A Case Study of an Authentic Learning Activity, the “Brain Game”,

to Develop 21

St

Century Skills in Context

Grace Lawlor and Brendan Tangney

Centre for Research in IT in Education, School of Education and School of Computer Science & Statistics,

Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Keywords: Constructivism, 21

St

Century Skills, Mantle of the Expert, Authentic Learning, Collaborative Learning.

Abstract: Making new meanings and relating them to existing knowledge and systems is at the heart of the constructivist

approach to learning. Authentic learning builds on this by exploiting the power of information and

communications technology (ICT) and is often delivered as a project based learning experience. Authentic

learning aligns well with the 21

st

Century (21C) approach to teaching and learning which emphasises the

development of key skills, such as problem solving, creativity and collaboration, along with the mastering of

curriculum content. Against this backdrop this study seeks to explore a particular approach to technology

mediated, authentic, project based, constructivist, 21C teaching and learning which uses the “Mantle of the

Expert” pedagogy from drama education as a way of structuring an innovative learning experience. Mantle

of the Expert learning explicitly uses role-play in which, within an imagined context, learners take on the role

of experts within an enterprise and work together to solve a problem. The “Brain Game” is a model activity

that immerses learners within an authentic context, collaborating with peers to manage a project within

deadlines. Technology is a central element of the intervention as it provides a means for learners to engage in

role-play through email, researching information online and producing deliverables. 144 students aged 13-14

from 11 schools participated in an exploratory case study involving two one-day workshops. The findings of

the study suggest that a technology mediated approach was effective in developing students’ 21C skills and

that “Mantle of the Expert” is an appropriate pedagogy to use in designing authentic learning experiences.

1 INTRODUCTION

Constructivist learning theory argues that students

can learn effectively when engaged in project based

learning, connecting knowledge and ideas while

guided by a teacher in a facilitating rather than direct

teaching role.

Authentic and Project based learning are two

strategies that resonate with Constructivist learning.

Authentic learning is characterised by activities based

on real-life, complex problems without binary

solutions (Lombardi, 2007). Herrington, Oliver and

Reeves (2003) propose that ten unique elements of

design make for authentic learning. These elements

are a broadly defined as: a challenge with real-world

relevance, collaborative learning, reflection,

integrated assessment, an investigation sustained over

a period of time, multiple information sources,

interdisciplinary content, provision for learners to

openly interpret outcomes and a deliverable product.

Project Based Learning (Thomas, 2000) involves

complex tasks, based on a problem or challenge that

engages students in problem solving, decision

making or designing, allowing students to work with

a degree of independence that leads to a deliverable

outcome (Jones, Rasmussen, and Moffitt, 1997;

Thomas, Mergendoller, and Michaelson, 1999).

Additional features of Project Based Learning include

the use of authentic content within the project,

teachers as facilitators (Moursund, 1999), and co-

operative learning (Diehl, Grobe, Lopez, and Cabral,

1999). The Project Based Learning approach lends

itself to the acquisition of 21

st

Century Skills, such as

collaboration, problem solving, etc. (Bell, 2010).

Although a body of literature can be found on

constructivist, authentic and project based pedagogy

and the perceived gains of their application for

learners, translation of these theories to tangible

activities for educators to implement with their

students could be further explored. This study

Lawlor, G. and Tangney, B.

Constructivist Learning and Mantle of the Expert Pedagogy - A Case Study of an Authentic Learning Activity, the “Brain Game”, to Develop 21St Century Skills in Context.

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2016) - Volume 2, pages 265-272

ISBN: 978-989-758-179-3

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reser ved

265

presents one such activity model the “Brain Game”

that could be applied to a range of topics to explore

content knowledge and to promote skills

development. This research also considers ways in

which technology and the drama pedagogy Mantle of

the Expert, both integrated in the design of the

activity model, can enhance learning activities that

are constructivist by nature.

The “Brain Game” can be based on any real-life

challenge or project a learner faces. In this study a

school leadership project provided a context for the

activity. 144 students participated in the research

project as part of their involvement with an action

research project focusing on changing school culture

(see www.tcd.ie/ta21). A core element of the project

is a “Leadership through Service” activity in which,

to help develop student leadership skills, each

participating school is required to carry out a

community service project, with the students leading

the venture. Each of the 144 students involved

participated in two training workshops of one day

each, in the Bridge21 learning space on the authors’

university campus.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Authenticity in Learning

Lombardi (2007) proposes that students become more

motivated to learn when learning tasks simulate their

real-life counterparts, as this gives a sense of

authenticity and relevance to learning. A broadly-

defined or ill-structured problem with numerous

possible solutions and interpretations can mirror the

complexities and facets of problems one encounters

in life (Hong 1998). Furthermore, approaching ill-

structured problems has been identified as a crucial

skill for educators to develop with students in their

schools (National Research Council, 1996). Using

multiple sources of information to solve a problem is

an element of authentic learning practice that requires

learners to critically evaluate and compare different

sources of information. This could help to develop

information literacy, a skill which has become a

growing interest for educators (Bruce, 1999;

Eisenberg, Lowe and Spitzer, 2004), and is a

component of the Partnership for 21

st

Century

Learning’s “Information and Media Literacy” subset

(Kay, 2010).

Thomas (2000) offers five criteria to be

considered as key elements of Project Based

Learning.

1. Projects take a central, not an ancillary place in

exploring curricular content.

2. The project is driven by a question or ill-defined

problem.

3. There is a process of constructive investigation

in which new skills and new understanding are

assimilated by the learners.

4. Projects are notably student-driven, allowing for

independence and some degree of choice.

5. Projects are authentic and not “school-like”.

It can be seen, that these criteria for Project Based

Learning share common elements with Authentic

Learning as defined by Lombardi (2007). Of

particular interest is the element of authenticity.

Thomas (2000) elaborates on this potential for Project

Based Learning to be authentic; by the context of the

project work, by the involvement of real-world

collaborators within the area of study and authentic

deliverables or the use of a real-world criteria for

assessing the projects. From his review of research on

Project Based Learning, Thomas (2000) observes that

students can find the challenge of self-directed

projects rewarding, particularly in such areas as time-

management and using technology effectively.

Another method of creating authenticity within

learning could be to actively engage learners and

teachers in role-play. Although role-play´s potential

as an aspect of project-based or authentic learning

remains to be fully explored, benefits of role-play in

learning have been long established (Blatner, 2013).

It is suggested that when engaged in role-play,

learners can apply content in a relevant context,

engage in decision making by adopting a new persona

and see the relevance of their learning for handling

real-world situations.

2.2 Mantle of the Expert

Mantle of the Expert is an inquiry based approach to

teaching and learning from the field of drama studies

(Heathcote, 1994). Students reach learning outcomes

by assuming roles as “experts” within an imagined

enterprise to solve a problem. It is proposed by

Heathcote (1994) that by taking on roles as experts,

children can experience the kinds of responsibilities,

challenges and problems that adults do in the real

word. In Mantle of the Expert learning, problems are

framed as professional tasks so that learning has a

relevant and immediate purpose (Aitken, 2013).

Abbot (2007) considers the crucial role of the

teacher in Mantle of the Expert learning - teachers

must structure tasks effectively. In this way teachers

are positioned as enablers of knowledge rather than

givers of knowledge (Heathcote and Herbert, 1985).

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

266

As well as presenting the context, the teacher’s role is

to maintain an element of tension by facilitating

further problems to be addressed as part of the main

task. These problems can either occur naturally as

discovered by the learners through their interactions

or can be strategically introduced by the teacher. This

element of tension and problem solving adds

authentic depth to the task, and furthermore scaffolds

students to realise the complexity of learning in the

real world (Aitken, 2013).

The Mantle of the Expert pedagogy proposes

more than just role play: learners are given status as

experts and this expert “mantle” of leadership,

knowledge, competency and understanding will grow

around the child as they work in an imagined context

(Aitken, 2013). For the development of skills and

acquisition of knowledge to occur successfully, the

teacher must prepare the ground carefully, combining

the core elements of Mantle of the Expert.

Although the Mantle of the Expert approach is

validated by studies of its application across the

primary level curriculum (James and Lewis, 2012),

there is vast potential to explore its viability as a

pedagogy for second level. Moreover, the use of

technology as a tool within Mantle of the Expert has

yet to be considered meaningfully. Integration of

technology with Mantle of the Expert could be an

interesting development of the pedagogy for the 21

st

Century.

3 RESEARCH FOCUS

This study explored the potential for developing 21st

Century skills within the context of a Mantle of the

Expert inspired, technology enhanced intervention,

called “Brain Games”. The approach fostered critical

thinking, collaboration, digital literacy and

communication. The activity involved: collaborative

working, real world information sources, authentic

deliverables, role play through email, ill-defined

problems, sustained pressure to meet deadlines,

critical thinking, digital literacy and communication.

The intervention was carried out using the

Bridge21 model of team-based technology-mediated

learning in a purpose designed learning space on the

authors’ university campus (Lawlor, Conneely and

Tangney 2010). The Bridge21 model has been shown

to be suitable for: fostering intrinsic motivation

(Lawlor, Marshall and Tangney 2015); promoting the

development of the 21

st

century skills of

collaboration, communication etc. (Johnston,

Conneely, Murchan, Tangney 2015); supporting peer

learning (Sullivan, Marshall, Tangney 2015) and

delivering curriculum content (Tangney, Bray and

Oldham 2015, Wickham, Girvan and Tangney 2016).

With its emphasis on teamwork, use of technology

and fostering skills Bridge21 offers a very suitable

pedagogical framework, and learning space, in which

to implement the “Brain Game” activity.

Within the study, the following questions were

addressed.

• How did the use of technology enhance the

Brain Game intervention?

• Which distinct skills were addressed and

developed in the intervention?

• How authentic was the experience for

participants in relation to the real community

projects they faced?

4 RESEARCH DESIGN AND

METHOD

144 students aged 13-14 from 11 schools attended

two stages of “Brain Game” workshops in the

Bridge21 learning space on campus as part of their

training for implementing community service

projects.

Stage One workshops introduced the participants

to the nature of community or school service projects.

After icebreakers it was explained to the teams (4

students per team) that for the remainder of the day

they would be taking part in an activity designed to

simulate the process of planning, researching and

developing a school based community service

project. As such projects typically happen over a

number of months the 2 hours dedicated to the

activity during the workshop reflected two months of

real time with approximately 30 minutes in the "Brain

Game" correlating to a month. It was explained to the

participants that each "month" had a number of

deadlines - such as gaining permission from the

Board of Management for their project, and

submitting monthly progress reports. Teams were

instructed that all communication they needed to

make during the activity should be done through

emailing "The Brain" which provided all outside

world contact such as school staff, sponsors, potential

guest speakers etc. Each team had two desktop

computers at their disposal to send emails and

research any information required online. (Teachers

fulfilled the role of the “Brain”).

At the end of the “Brain Game”, teams presented

on their experience to their peers, highlighted what

they had managed to achieve and the challenges they

had encountered.

Constructivist Learning and Mantle of the Expert Pedagogy - A Case Study of an Authentic Learning Activity, the “Brain Game”, to

Develop 21St Century Skills in Context

267

The Stage Two workshops were held two months

later. In that time the school groups were encouraged

to discuss and explore potential projects they would

like to take on. The depth of this exploration varied

between schools but all school groups arrived at the

stage two workshops with chosen topics for their

projects and these were the focus of planning for the

day.

Following the initial ice-breakers and team

building exercises, the participants were again

divided into teams of four. Participants were

reminded about how the "Brain Game" worked,

which was similar to Stage One except this time each

team was responsible for their own activity and

regularly communicating with their larger school

group. The inter-team communication was facilitated

by "monthly" school committee meetings with

representatives from each small group meeting to

compile a progress report to send (via the "Brain") to

the board of management. The sub-committee design

of the stage two "Brain Game" was introduced to

offer the participants some experience of managing

an expansive workload by breaking into smaller

teams, each responsible for a specific area of the

project.

5 DATA COLLECTION AND

FINDINGS

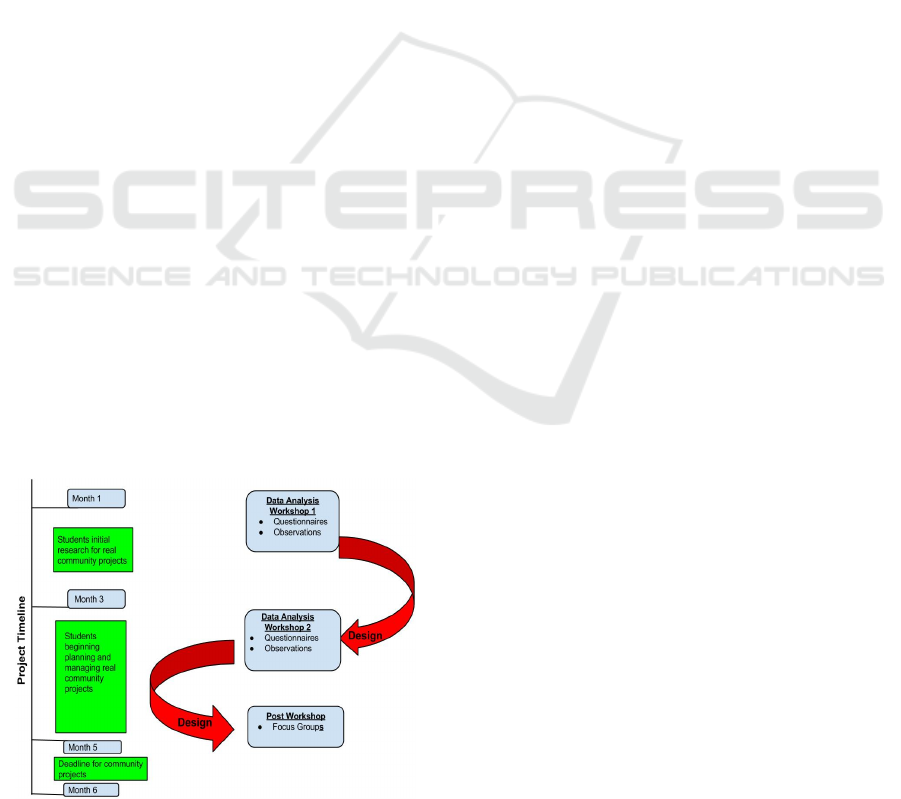

Data collection was structured as follows: direct

observation during the workshops; post workshop

questionnaires following both workshops (n=100 and

n=123 respectively) and focus group interviews (n=2)

following the implementation of the participants´

community service projects. This provided an

opportunity for each data collection stage to influence

the design of the next as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 : Data Collection Timeline.

Questionnaires were comprised of statements

with Likert scales and open response spaces to justify

or comment on Likert choices. An open coding

process was used to extract codes from these open

responses and grouped by four emergent themes;

• ICT skills development.

• Intervention being realistic or life-like.

• Relevance to actual community service

projects.

• Other skills development.

5.1 Participants Perceived Value of

Experience

When asked to indicate their perceived value of the

experience of the “Brain Game” intervention in both

workshops students gave a significantly positive

response (n=123) with 118 responding with “Very

Valuable” or “Valuable”. When asked why they

answered as they did, 94 participants provided

responses. 36 referenced working on a team with

students from another school being worthwhile. 28

mentioned reality or real-life and how they felt that

this workshop had prepared them for either the reality

of the community project they faced, other named

projects or generally coping under pressure. Although

these two reasons emerged as the most commonly

shared amongst the participants, there were a variety

of other reasons students found this experience

valuable including the use of technology. It was also

mentioned that the workshops were fun or enjoyable.

Open responses speaking to this theme included

the following.

“Great questions by brain like real life.”

”It helps you to be a better leader, to

communicate with others and to organise things”.

5.2 Participants Perception of

Technology in Intervention

When asked how useful they considered the

application of computers in both workshops, 111

participants chose “Very Useful” or “Useful”

(n=123). The most prevalent theme that emerged

from the open responses was the beneficial use of

email within the intervention. This could reflect both

the basic act of emailing and the more challenging

skill of using email as a means of formal

communication. What the researcher considers to be

a more relevant issue is that at beginning the

workshops participants did not display experience in

using email as a means of formal communication.

Teacher and mentor observations as well as the

researcher’s analysis of email exchanges at Stage One

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

268

workshops noted the participants’ lack of

understanding on how to structure a formal

correspondence in email. For example crucial pieces

of information were omitted, text-speak and

inappropriately casual language were used. It was

conveyed in the focus group interviews that

participants’ were using email with some degree of

success in communicating with stakeholders in order

to implement their real community service projects,

which could suggest a transfer of some formal

communication skills. Participants said:

“It helped me organise things like emails for

events.”

“It´s how you communicate with companies”

“Because we got some questions from teachers

and gave us ideas”.

Other responses on the use of computers

mentioned how they could access online information

during the intervention using the computers:

“We had access to a lot of useful information and

we could make better decisions with this”

“We needed to estimate the prices of things we

needed to get.”

From focus group interviews there was some

evidence that participants were accessing information

online to research and develop their real community

projects.

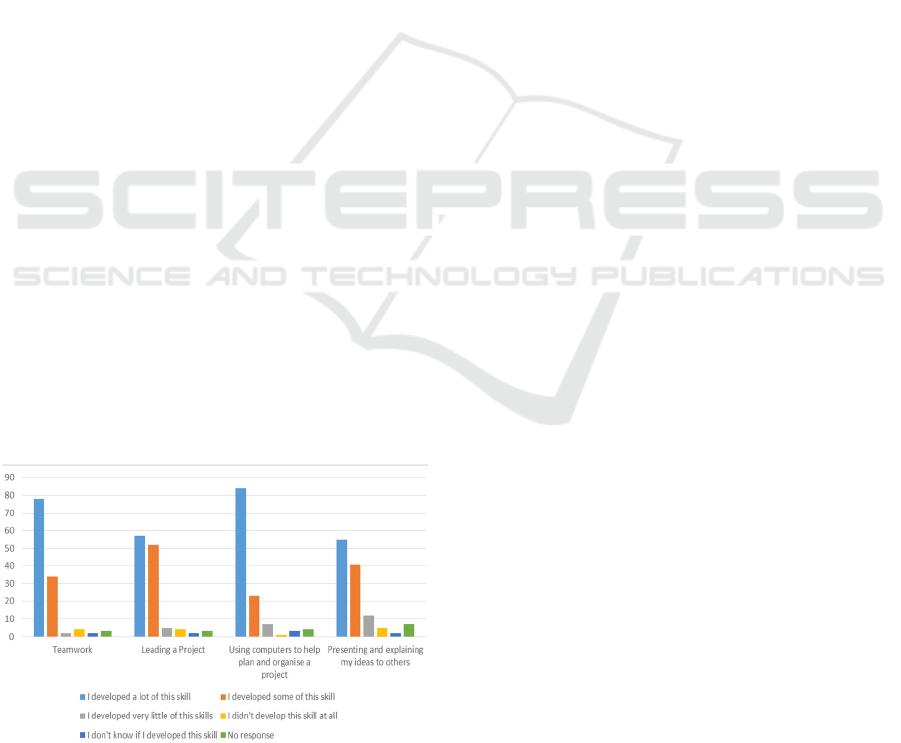

5.3 Potential for Skills Development

The analysis of stage one data suggests that the

students perceived themselves as has having

developed four main skills: teamwork; leading

projects, using computers to help plan and organize

projects and presenting ideas to others. In stage two

questionnaires, the participants were asked to indicate

on a Likert scale to what extent they felt they had

developed each of these skills.

Figure 2 : Participants perception of skills developed during

the workshops.

In the “Brain Game” intervention, participants’

were working together towards a shared outcome,

sharing responsibilities by taking on roles within the

team and supporting one another. Therefore, it was

unsurprising that participants’ self-reporting of

developing skills in collaborative working emerged

strongly from the data. This was further supported by

the results of the Likert scale shown in Figure 3

above. Regarding communication skills, it is not

absolutely clear whether participants meant that they

gained experience from the internal communications

of their team within the workshops, their

communications with the “Brain” or by presenting

their ideas and experiences to others. The authors

suggest that it likely to be a combination of all three.

In the two focus groups participants mentioned

instances of communicating either with their peers or

with external stakeholders to implement their real

community projects and related this back to skills and

experience they had gained from the workshops.

Two focus group interview, with small groups of

students, were conducted by the researcher two

months after the stage two workshops. These

interviews provided an opportunity to further explore

the finding of the stage one and two questionnaires.

During this time the interviewees were engaged in

implementing their real community service projects.

The interviews were semi-structured and focused on

participants’ experience of the intervention and

implementing the real projects. Emergent themes

from the interviews included a perceived transfer of

skills from the intervention to the real projects and

how realistic they felt the “Brain Game” was as an

activity:

“It helped us in my opinion really much because

we got advice and how to work as a team and how to

plan and organize stuff.”

“You felt like you were actually proper working in

an office.”

”It makes you feel like really grown up or

something.”

6 DISCUSSION

Based on analysis of data collected, the authors

contend that the “Brain Game” intervention provided

a valuable authentic learning experience for

participants. Findings suggest that through their

experience of the workshops the participants

evidenced increased confidence in their ability to

implement their community service projects, in

working in collaboration with their peers and had a

greater sense of independence. There was also strong

Constructivist Learning and Mantle of the Expert Pedagogy - A Case Study of an Authentic Learning Activity, the “Brain Game”, to

Develop 21St Century Skills in Context

269

self-reporting that they had developed skills in

collaborative working, communication skills, critical

thinking and digital literacy, through their

engagement with the ”Brain Game”. Some evidence

suggests that for at least the focus group participants

that these skills transferred to their work on the

community service project.

6.1 Use of Technology

A consistent theme, throughout the data collected at

all three stages, was the participants’ perception that

they had gained skills in using computers – c.f. Figure

2. This acknowledgement of developing general ICT

skills was not always elaborated upon by the

participants but data suggests that this is related to the

summation of all ICT experience encountered by the

participants during the workshops including

emailing, researching information and other skills in

document editing etc.

Arguably, the most significant contribution

technology made in the intervention was to enable an

authentic role-play through email. An issue, strongly

emerging from qualitative data, was that the

intervention was “realistic” therefore allowing

participants’ to immerse themselves in the simulation.

An “imagined context” to develop authentic skills and

knowledge is at the core of the Mantle of the Expert

teaching pedagogy (Heathcote and Bolton, 1994) in

which learners adopt the role of experts within an

enterprise to solve a problem framed and sustained by

their teacher. The research suggests that this element

of belief or investment in the simulation on the part

of the participants could not have been as strong

without email providing a platform for role-play

exchange between the participants and their teachers.

A significant theme from the qualitative data is

that participants felt that they had gained experience

in emailing as a result of the workshops. This could

reflect both the basic act of emailing and the more

challenging skill of using email as a means of formal

communication.

Participants suggested that they had learned how

to send an email and this is supported by observations

during the Stage One Workshops where a number of

participants initially had issues with attaching

documents and sending mail. Although not a question

asked directly of participants in questionnaires, this

suggested that the many of participants were

unfamiliar with the basic procedures of email. This

echoes the findings of (Bennett, Maton and Kervin

2008) that young people are not always the

technically sophisticated “digital natives” they are

sometimes assumed to be. Aside from knowledge of

the mechanics of email, the participants’ lack of skill

and experience in structuring formal correspondence

emerged as an interesting finding from the study and

suggests that the typical protocols which adults apply

to the use of email may not map to adolescents, as

participants tended to initially transfer a style of

language used in communication technologies

familiar to them such as texting and social media

messengers to formal email correspondence. Van Der

Meij and Boersma (2002) caution that pre-adolescent

understanding and perception of using email is

removed from its typical adult business usage. A

further study could isolate and give further

consideration to the components of formal

communication skills developing in relation to the

intervention.

Exchanges with the “Brain” prompted students to

seek out information online, with participants’

engaging in tasks such as quoting prices of materials

they would need for their project or finding out the

opening hours of venues. Observations of participants

at the Stage One Workshops implied that although

certainly capable of searching for information online,

participants lacked the higher order skills to assess

and consider which sites would be more relevant,

appropriate or helpful. The mentors, who helped the

teams during the workshops, provided some support

in this regard by suggesting types of websites to

participants. From the focus group interviews,

participants acknowledged the transfer of the skill of

finding information online in the workshops to the

implementation of their real community projects,

asserting that it was something they could do “for

themselves”. It also empowered learners to actively

seek out information, rather than rely on a teacher to

provide it. This kind of autonomy and self-direction,

through which internet access can empower students,

has been identified by (Mitra and Dangwal, 2010) as

having powerful potential in learning.

In a further study, this aspect of developing digital

information literacy could be investigated to a greater

extent.

6.2 Skills Development

At all stages of data collection, the participants made

reference to skills that they perceived they had gained

of as a result of their participation in the intervention.

These skills were referred to in the context of general

personal awareness of a rise in confidence and

personal reflection on the sense of attainment of these

skills.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

270

6.2.1 Collaborative Work

Collaborative working is considered a key “learning

and innovation skill” within the Partnership for 21

st

Century Skills framework (Kay, 2010) and is a core

element of the Bridge21 learning model. Following

the use of technology, teamwork was reported by

participants as the second greatest area of skills

development. In addition to acknowledging the

development of collaborative working skills, many

participants also offered reasons why they thought

this skill was important to develop in relation to work

and college. An interesting point to note was that the

students mentioned the future beyond school and not

school itself when recognising the need to develop the

skill of working collaboratively. This may point at a

lack of opportunity as perceived by students to work

collaboratively at school, and also the participants’

own understanding of the ability to collaborate as a

life skill.

6.2.2 Communication Skills

The “Brain Game” intervention afforded participants’

an authentic opportunity to develop their

communication skills in the areas of interpersonal

communication, presentation in public and formal

writing. In both Stage One and Stage Two post-

workshop questionnaires there was self-reporting on

the development of these skills. There was also some

evidence of the transfer of these skills from the

workshops to the participants’ implementation of the

real community service projects as reported in the

focus group interviews The researcher contends that

a further study could isolate and examine the different

opportunities for developing communication skills

that the intervention affords, in particular the concept

of formal correspondence.

7 CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this study suggest that the “Brain

Game” intervention was perceived by participants as

a valuable and engaging learning experience.

Furthermore, participants self-reported the

development of key constructivist skills including,

collaboration, communication, and digital literacy.

While follow up focus group interviews suggested

that the “Brain Game” served as an impetus for

putting these skills into practice with the real

community projects. But the workshops were more

than a practice run. Fundamentally, the “Brain Game”

immersed students in an authentic context within a

team of peers to solve a problem. This immersion

scaffolded the development of skills and knowledge

needed for their real project by the learners through

their engagement with the task. While this

implementation can be considered as a positive

endorsement of the “Brain Game”, an advanced

exploration of the method applied to a number of

learning contexts would give greater validity and

reliability to the findings. Within the bounds of this

study, the “Brain Game” is presented as an innovative

model for authentic learning, greatly enhanced by

technology as a means of role-play, sourcing

information online and working within deadlines to

produce deliverables. Students both enjoy and value

learning of this nature as they can gain greater

confidence to manage projects and develop necessary

skills for 21

st

Century Society.

REFERENCES

Abbott, L. 2007. Mantle of the Expert 2: Training materials

and tools. Essex, UK: Essex County Council.

Aitken, V. 2013. Dorothy Heathcote’s Mantle of the Expert

approach to teaching and learning: A brief

introduction. Connecting curriculum, linking learning,

34-56.

Bell, S. 2010. Project-based learning for the 21st century:

Skills for the future. The Clearing House, 83(2), 39-43.

Bennett S., Maton K., and Kervin L. 2008. The ‘digital

natives’ debate: A critical review of the evidence.

British journal of educational technology. 39(5): p.

775-786.

Blatner, A. 2013. Warming-up, action methods, and related

processes. The Journal of Psychodrama, Sociometry &

Group Psychotherapy, 61 (2).

Bruce, C. S. 1999. Workplace experiences of information

literacy. International journal of information

management, 19(1), 33-47.

Diehl, W., Grobe, T., Lopez, H., & Cabral, C. 1999. Project-

based learning: A strategy for teaching and learning.

Boston, MA: Center for Youth Development and

Education, Corporation for Business, Work, and

Learning.

Eisenberg, M. B., Lowe, C. A., & Spitzer, K. L.

2004. Information literacy: Essential skills for the

information age. Greenwood Publishing Group, 88 Post

Road West, Westport, CT 06825.

Heathcote D, & Bolton G 1994. Drama for learning:

Dorothy Heathcote’s Mantle of the Expert approach to

education. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann Press. Heston,

Heathcote, D., & Herbert, P. 1985. A drama of learning:

Mantle of the expert.Theory into practice, 24(3), 173-

180.

Herrington, J., Oliver, R., & Reeves, T. C. 2003. Patterns of

engagement in authentic online learning

Constructivist Learning and Mantle of the Expert Pedagogy - A Case Study of an Authentic Learning Activity, the “Brain Game”, to

Develop 21St Century Skills in Context

271

environments. Australian journal of educational

technology, 19(1), 59-71.

Hong, N.S., 1998. The relationship between well-structured

and ill- structured problem solving in multimedia

simulation. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. The

Pennsylvania State University Press.

James, M and Lewis, J. 2012. Third Generation Assessment

in a Primary Classroom In Gardner, J.N and Gardner J.

(Eds.) Assessment and Learning (2012). Sage.

Jones, B. F., Rasmussen, C. M., & Moffitt, M. C. 1997.

Real-life problem solving: A collaborative approach to

interdisciplinary learning. Washington, DC: American

Psychological Association.

Johnston K., Conneely C., Murchan D., Tangney B. 2015,

Enacting key skills-based curricula in secondary

education: lessons from a technology-mediated, group-

based learning initiative. Technology, Pedagogy and

Education, 2015. 24(4): p. 423-442.

Kay, K. 2010. 21st century skills: Why they matter, what

they are, and how we get there. 21st century skills:

Rethinking how students learn, 2091-2109.

Lawlor, J., Conneely, C., & Tangney, B. 2010. Towards a

pragmatic model for group-based, technology-

mediated, project-oriented learning–an overview of the

B2C model. In Technology Enhanced Learning.

Quality of Teaching and Educational Reform (pp. 602-

609). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Lawlor J., Marshall K., Tangney B. 2015. Bridge21 –

Exploring the potential to foster intrinsic student

motivation through a team-based, technology mediated

learning model, Technology, Pedagogy and Education,

1-20.

Lombardi, M. M. 2007. Authentic learning for the 21st

century: An overview. Educause learning

initiative, 1(2007), 1-12.

Mitra, S., & Dangwal, R. 2010. Limits to selforganising

systems of learning—the Kalikuppam

experiment. British Journal of Educational

Technology, 41(5), 672-688.

Moore, R., Lopes, J., 1999. Paper templates. In

TEMPLATE’06, 1st International Conference on

Template Production. SCITEPRESS.

Moursund, D. 1999. Project-based learning using

information technology. Eugene, OR: International

Society for Technology in Education.

Sullivan K., Marshall K., and Tangney B. 2015. Teaching

without teachers; peer teaching with the Bridge21

model for collaborative technology-mediated learning.

Journal of IT Education: Innovation in Practice, 2015.

14: p. 63-83.

Tangney B., Bray A., and Oldham E. 2015. Realistic

Mathematics Education, Mobile Technology & The

Bridge21 Model For 21st Century Learning – A Perfect

Storm, in Mobile Learning and Mathematics:

Foundations, Design, and Case Studies, Crompton H.

and Traxler J., Editors. Routledge. p. 96-105.

Thomas, J. W. 2000. A review of research on project-based

learning. Retrieved from

http://www.bobpearlman.org/BestPractices/PBL_Rese

arch.pdf 1/Feb/2016.

Van Der Meij, H., & Boersma, K. 2002. Email use in

elementary school: An analysis of exchange patterns

and content. British Journal of Educational

Technology, 33(2), 189-200.

Wickham C., Girvan C., and Tangney B. 2016.

Constructionism and microworlds as part of a 21st

century learning activity to impact student engagement

and confidence in physics, in Constructionism 2016.

Bangkok. In press.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

272