Anaís: A Conceptual Framework for Blended Active Learning in

Healthcare

Adriano Araujo Santos

1

, José Antão Beltrão Moura

2

, Joseana Macêdo Fechine Regis de Araújo

2

and Marcelo Alves de Barros

2

1

Graduate Program in Computer Science from the Federal University of Campina Grande – UFCG,

Higher Education and Development Center – CESED, Campina Grande, Brazil

2

Systems and Computing Department, Federal University of Campina Grande, DSC/UFCG, Campina Grande, Brazil

Keywords: Anaís Conceptual Framework, Active Learning, Learning Process, Active Learning System, Blended

Learning, Medicine, Healthcare.

Abstract: The guarantee of the right to quality education is a fundamental principle for policy and management

education. In addition to the organizational processes and regulation, as well as for citizenship, currently the

student satisfaction plays a key role for the adequacy of actual courses and the needs of the educational

community who depend on them. This way, interest on active methodologies has intensified with the

emergence of new strategies that may favour the autonomy of students. Active Learning (AL) becomes an

important strategy in healthcare to the extent that theory and practice go hand in hand in the training of

health experts. This paper proposes a conceptual framework (Anaís) for active learning in healthcare studies

and summarizes a qualitative research with healthcare experts and students on the feasibility and

applicability of Anaís and its potentially positive results. Statistical tests and descriptive analysis of the

collected data indicate Anaís could indeed bring a contribution to the healthcare area in terms of benefits to

use it as an AL tool for professional training of physicians and other healthcare professionals and specialists.

1 INTRODUCTION

One of the great challenges of this new century is

balancing development of individual autonomy in

relation to that of the collective. Exploring

innovative methods that admit a pedagogical and

ethical practice at the same time that they offer

critical, reflective and transformative instruction

seems popular in the current context of education

and university curricula. Such methods are expected

to exceed the limits of purely technical training to

create new challenges that motivate students. In this

context, active methodologies studies have

intensified with the emergence of new strategies that

favour the autonomy of students, from those with the

simplest requirements to those who need physical or

technological readjustment of educational

institutions (Farias et. al, 2015

).

Active Learning (AL) instructional strategies

include a wide range of activities that share the

common element of involving students in doing

things and thinking about the things they are doing

(Bonwell and Eison, 1991). AL systems can be

created and used to engage students in (a) thinking

critically or creatively, (b) speaking with a partner,

in a small group, or with the entire class, (c)

expressing ideas through writing, (d) exploring

personal attitudes and values, (e) giving and

receiving feedback, and (f) reflecting upon the

learning process (ElDin, 2014). These interactive-

learning strategies offer students opportunities to

connect new information to their own experiences,

providing them with models for applying new

knowledge, and promoting cognitive skills.

Numerous models or strategies for clinical

teaching have been described in the medical

education literature. Recently, the inseparability of

theory and practice, the integral vision of man and

the expansion of careful design have become

essential for proper work performance (Souza,

Iglesias and Pazin-Filho, 2014).

Day after day, specialist physicians carry out

complex health analyses and must make decisions

which might be fatal, in case they are erroneous.

Santos, Moura and Araújo (2015) propose a

conceptual framework (“Anaís”) for helping in the

Santos, A., Moura, J., Araújo, J. and Barros, M.

Anaís: A Conceptual Framework for Blended Active Learning in Healthcare.

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2016) - Volume 2, pages 199-206

ISBN: 978-989-758-179-3

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

199

analysis and decision-making process of rare clinical

cases. The framework is based on the association of

medical evidence analysis techniques, knowledge

management and collective intelligence in order to

mitigate the risks and uncertainty faced by specialist

physicians. Anaís could also be used as an

educational tool, to help train health professionals.

The educator can set up controlled cases and submit

them to physicians being trained, so that they can

give their opinions, in a simulated environment,

building knowledge by means of interactions among

the students. This paper brings results of a

preliminary investigation on the potentiality and

usefulness of using Anaís as an AL tool for

professional training of specialist physicians.

2 RELATED WORK

The contents of this paper directly relate to Active

and Blended Learning (BL) research efforts in

higher education in general. Of particular interest are

those works that consider audiences that need to

build a knowledge expertise to make complex

decisions such as in medical diagnosis (Dx)

situations (with a computer-supported tool in

special).

The work “Web 2.0 to Support the Active

Learning Experience” showed a discussion of the

active learning literature and the appropriateness of

such strategies with net generation learners is

provided (Williams and Chinn, 2009). The study

also details the implementation of this experience

within the curriculum, and assesses the benefits and

challenges related to enhanced student learning and

engagement as well as literacy outcomes. The

authors observed that increased student engagement

was noted in both instructor and student evaluations

of the assignment.

Parmelee, DeStephen and Nicole (2009) showed

a comparative study of how medical students’

attitudes about the Team-Based Learning process

changed between the first and second year of

medical school with 180 students commenting on 19

statements regarding their attitudes about Team-

Based Learning. The result demonstrated that

students’ attitudes about working within teams, their

sense of professional development, and comfort and

satisfaction with peer evaluation improve a

curriculum using Team-Based Learning.

Cayley (2011) reviewed four specific clinical

teaching strategies and the evidence for their impact

on educational outcomes or office efficiency.

Literature for this review was selected based on the

results of a Pub Med search on the terms “medical

student” and “precepting”, review of references in

retrieved articles, and the author’s personal files.

The research conclusion was that OMP and

SNAPPS are strategies that can be used in office

precepting to improve educational processes and

outcomes, while pattern recognition and activated

demonstration show promise but need further

assessment.

Mitre et. al. (2008) aims to discuss the main

methodological transformations in the education

process of health professionals, with emphasis on

active teaching-learning methodologies. Authors

affirmed that the collective reflection, dialogue,

recognition of context and new perspectives are the

basis for the building of new avenues in the search

for wholeness of body and mind, theory and

practice, teaching and learning, reason and emotion,

science and faith, competence and loveliness. Only

through a reflective practice, critical and committed

can promote independence, freedom, dialogue and

confrontation of resistance and conflict.

Nilsson et. al. (2010) explored how clinical

teaching is carried out in a clinical environment with

medical students, looking for meaning patterns,

similarities and differences in how clinical teachers

manage clinical teaching; non-participant

observations and informal interviews were

conducted during a four month period 2004-2005.

The findings showed that three superordinate

qualitatively different ways of teaching could be

identified that fit Ramsden’s model (Ramsden,

1984).

Zaher and Ratnapalan (2012) had the objective

of identifying the format, content, and effects of

practice-based small group learning (PBSGL)

programs involving Family Physicians. Authors

affirm that there exist two main PBSGL formats

(self-directed learning and specific problems from

practice) and both formats are similar in their

ultimate goal, equally important, and well accepted

by learners and facilitators. Perceptions and learning

outcomes indicate that PBSGL constitutes a feasible

and effective method of professional development.

De Jong et. al. (2012) proposed three cases of

blended, active and collaborative learning, using a

virtual classroom, Second Life immersive virtual

world and discussion forums, blogs and wikis. They

wanted to know if blended learning can be active

and collaborative and the results of the three cases

clearly show that active, collaborative learning at a

distance is possible.

Mubuuke, Louw and Schalkwyk (2016)

proposed exploring students’ experiences of

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

200

feedback delivery in a PBL tutorial and use this

information to design a feasible facilitator feedback

delivery guide. Individual interviews and focus

group discussions were conducted with students who

had an experience of the tutorial process in an

exploratory qualitative study. The study has

demonstrated that PBL facilitators need to provide

comprehensive feedback on the knowledge

construction process as well as give feedback on

other non-cognitive skills outside the knowledge

domain including effective communication,

adherence to ground rules and maintenance of group

dynamics.

The work “Developing an integrated framework

of problem-based learning and coaching psychology

for medical education: a participatory research”

explored a new framework by integrating the

essential features of PBL and coaching psychology

applicable to the undergraduate medical education

context (Wang et. al., 2016). Five themes emerged

from the analysis: current experience of PBL

curriculum; the roles of and relationships between

tutors and students; student group dynamics;

development of self-directed learning; and coaching

in PBL facilitation. Authors anticipate that their

investigations are useful in two ways. First, the

Coaching + PBL Model could serve to stimulate

consideration and debate as institutions develop their

own PBL concepts and procedures. Second, their

study provides insights into incorporating coaching

skills into professional development programmes for

PBL tutors and PBL curricula for students.

Blended Learning (BL) combines face-to-face

and online learning to create variable sequence of

knowledge acquisition and sharing (Bersin, 2004;

Graham, 2006). BL experiments have since evolved

to deal with richer blending options to produce

“hybrid courses” and have become frequent in

particular in many university and other higher

education courses. (CSEDU, 2010-2014). In these

hybrid courses or “flipped” classrooms, students

engage in content learning before classes in order to

maximize in-class time for active learning. In-class

active learning helps produce significant learning as

learners practice with, engage with, and apply pre-

class learning. Although experimentation with

Blended Learning (BL) is on the rise in all fields of

education, the work of Drysdale et al., (2013)

indicates that much of it is carried out at the

university level as it is the case here with our target

audience of medicine students. The works

considered in (Drysdale et al., (2013) – over 200

graduate dissertations and theses on BL – relate to

this paper in the sense that in one way or another

they investigate the benefit of BL-programs over

traditional face-to-face programs.

Subjective outcomes such as learning

effectiveness, cost effectiveness, institutional

commitment, student satisfaction, faculty

satisfaction, etc. were described (Moore, 2005).

(Arano-Ocuaman, 2010) noted that students

preferred BL classes compared to traditional classes

in the following areas: “(a) accessibility and

availability of course materials; (b) use of web-based

or electronic tools for communication and

collaboration; (c) assessment and evaluation; and (d)

student learning experiences with real-life

applications”. Similar results were found by (Barros

et al., 2015) for an innovative approach that brings

together BL and gamification strategies to a learning

process.

All these approaches suggest that, besides the

computer-based and blended learning approaches,

there is an important role played by the instructor

and students in the learning group or organization:

the role of a knowledge manager that conducts and-

or experiments a tacit-to-explicit-to-tacit knowledge

conversion cycle as preconized by Nonaka and

Takeuchi in their knowledge spiral model (Nonaka

and Takeuchi, 1999). This cycle is made up of four

modes of knowledge conversion: socialization (tacit

to tacit), externalization (tacit to explicit),

combination (explicit to explicit) and internalization

(explicit to tacit). Accordingly, before analyzing the

performance of a specific BL approach, such as that

in Anaís, against face-to-face or other learning

strategies for our target audience, it seems

appropriate to evaluate the acceptance of the

approach by the instructor as a facilitator to create

and validate different blended learning options to a

specific domain course. In this paper, we do that for

Anaís for the case of healthcare studies.

To do this we use Anaís to compose an

innovative BL environment for education in a

healthcare learning context, highlighting the

knowledge management sub-processes. This enables

the combination of tacit-to-explicit-to-tacit

knowledge conversion cycle in routine activities of a

healthcare specialist (e.g. Anamnesis process, Lab

tests) to computational techniques. The combination

thus helps the exchange of experiences amongst

participants of a healthcare team and the support of

the collective learning process.

Anaís: A Conceptual Framework for Blended Active Learning in Healthcare

201

3 ANAÍS CONCEPTUAL

FRAMEWORK

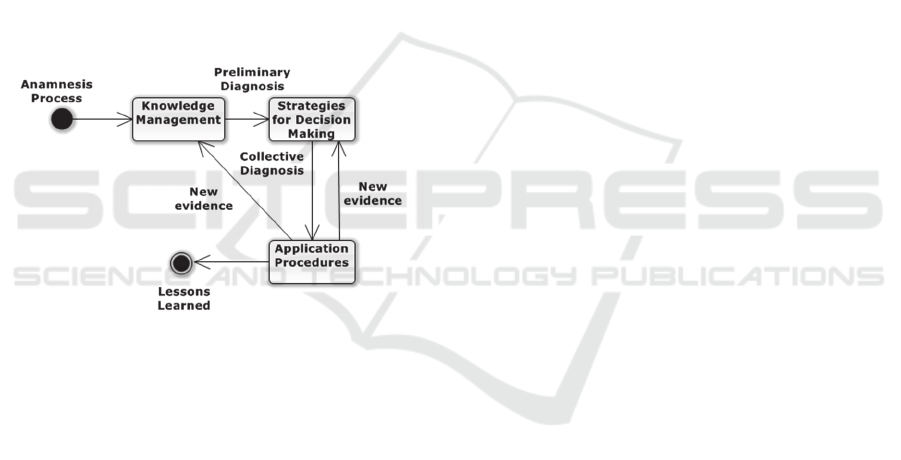

The Anaís Conceptual Framework comprises five

macro stages as illustrated in Figure 1, namely: a)

Anamnesis Process; b) Knowledge Management; c)

Decision Strategy; d) Application of Procedures and

e) Learned Lessons.

Each stage presented in the framework comprises

a set of pooled techniques which receives,

sequentially, the outputs of the previous stages. The

specialist physician in charge of the analysis of the

case is responsible for the Anamnesis, Knowledge

Management and Application of Procedures stages.

The Decision Strategy stage makes use of the Delphi

method in an attempt to achieve convergence of the

opinions of experts in the decision-making process.

The end of the process is the generation of a new

case, which is stored on the Learned Lessons

database (Santos, Moura and Araújo, 2015).

Figure 1: Anaís Conceptual Framework.

To produce the main learning outcome

(diagnosis decision making ability) the hybrid

learning concept supported by ANAÍS is created by

the movement between the three spaces of the

apprentice experience combined with the formal

"spiral" based process of knowledge conversion.

This combination blends 3 learning concepts: a)

syncronous and assyncronous computer suported

online learning experience helped by knowledge

repositories and interactive research processes, b)

active attitude of build knowledge supported by

responsible relationships with coleagues, instructor

and patients, and c) cognitive development produced

in conventional classroom and-or clinical laboratory

activities.

4 METHODOLOGY

This research is classified as an applied and

qualitative research. It aims to get the opinion of a

group of health experts and students (the target

audience of the research) on the feasibility and

applicability of the proposed Anaís framework as a

support tool to blended active problem based

learning (BAL).

We selected 60 persons using a random method

selection, 30 experts who work in Brazil's Northeast

(in the state of Paraíba) as health professionals,

academics and researchers and 30 students of

medicine. In the experiment process, we used the

Think Aloud Protocol (Think Aloud, 2016) to ensure

that all the participants understood the framework.

The reason to select students and experts in health is

analysing two different expertise and if the both

thinks the same form about the solution.

We wanted to know whether experts and

students of medicine believe that the Anaís

conceptual framework can be used as an AL tool for

professional training of specialist physicians. For

this, we developed an Anaís Conceptual Framework

to Active Learning based system. All the

participants used this system and gave their opinions

about it. They answered a questionnaire where

possible responses were in the form of a 4-level

Likert based scale: Strongly disagree = 0; Disagree =

1; Agree = 2; and, Strongly agree = 3. The sentences

presented to them were:

A. I believe that the Anaís conceptual

framework can be used as an AL tool for

professional training of specialist physicians.

B. I am satisfied with the Anaís conceptual

framework based system for active learning

and could identify many effective

contributions for the healthcare area.

C. I consider the model useful and I would

invest (time, specification effort, testing,

etc.) in its evolution.

5 ANAÍS BASED HYBRID

BLENDED ACTIVE LEARNING

The main learning outcome of the Anaís blended

active learning approach is the capability to produce

a diagnosis of a case study. Problem enunciation

(case) is proposed by the instructor and problem

analysis (case study) by the students who offer their

solution (diagnosis) with the possible assistance of

the instructor and invited professional experts on the

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

202

healthcare case.

Activities are carried out by each group of

students in three spaces: i) the physical space of the

classroom used for intra- and inter-group, lecturer-

mediated communications, including face-to-face

classes and oral exams; ii) a virtual space in the Web

(“Anaís BAL”) that serves to synchronize and

support learning activities, including mandatory

Web lessons; to register discussion contents of the

groups; to filter initial diagnosis proposals; to

research information produced by groups in previous

cases (and saved in the Anaís BAL repository);

research of data available in the linked medical

databases as PubMed –

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/; and, iii) the real-

world surroundings of the students´ living spaces.

Students move between spaces as they are exposed

to a sequence of situations during the case study

period defined by the instructor.

The learning process is composed of 5 steps

during which, students: i) receive from the instructor

a case to study. The student leader of a group

conducts the study; ii) go through their living spaces

to carry out an anamneses while entering of data into

the web tool; iii) build collective intelligence by

converting knowledge using a Nonaka and Takeuchi

spiral to produce preliminary diagnoses; iv) make

decisions and produce a collective, convergent

diagnosis from the preliminary diagnoses; v) register

the results of case study in the Learned Lessons

database.

Initially, only cases for cardiology and

ophthalmology domains were considered (Fig 4).

Convergence was facilitated by a Delphi method

(Hsu and Sandford, 2007). Anaís BAL support for

the Nonaka and Takeuchi knowledge management

model spiral is as follows.

Socialization (tacit-to-tacit) – Anaís allows the

instructor, experts and students to share tacit

knowledge through observation, imitation, practice,

and participation in the groups and in the formal and

informal communities created around the 3 spaces of

Anaís BAL environnement. Externalization (tacit-

to-explicit) is supported by making instructor,

experts and students articulate tacit knowledge into

explicit concepts. Since tacit knowledge is highly

internalized, this process is the key to knowledge

sharing and creation to develop the collective

intelligence. Combination (explicit-to-explicit) is an

Anaís process by which students integrate different

registered knowledge used to create their

preliminary diagnoses and the final collective

diagnosis into a new knowledge system, represented

here by a new case registered in the Learned Lessons

repository -that becomes a new tool of knowledge

creation. Finally, Internalization is achieved by

embodying explicit knowledge into tacit knowledge,

by researching and reading the internal and external

sources of registered offered by Anaís BAL

repositories.

The software platform for Anaís BAL was

developed using the Visual Studio 2012 with

Microsoft ASP.NET MVC 4, Entity Framework 4

and SQL Server 2008 Express, Apache Solr 5.1.0

(text indexing), SolrNet, GoldenTrack 2009

(http://lightbase.com.br/tag/goldentrack/),GoldenAc

cess 1.2.4 (authentication system), PubMed API for

.NET, Twitter Bootstrap (UI framework –

http://getbootstrap.com/2.3.2/).

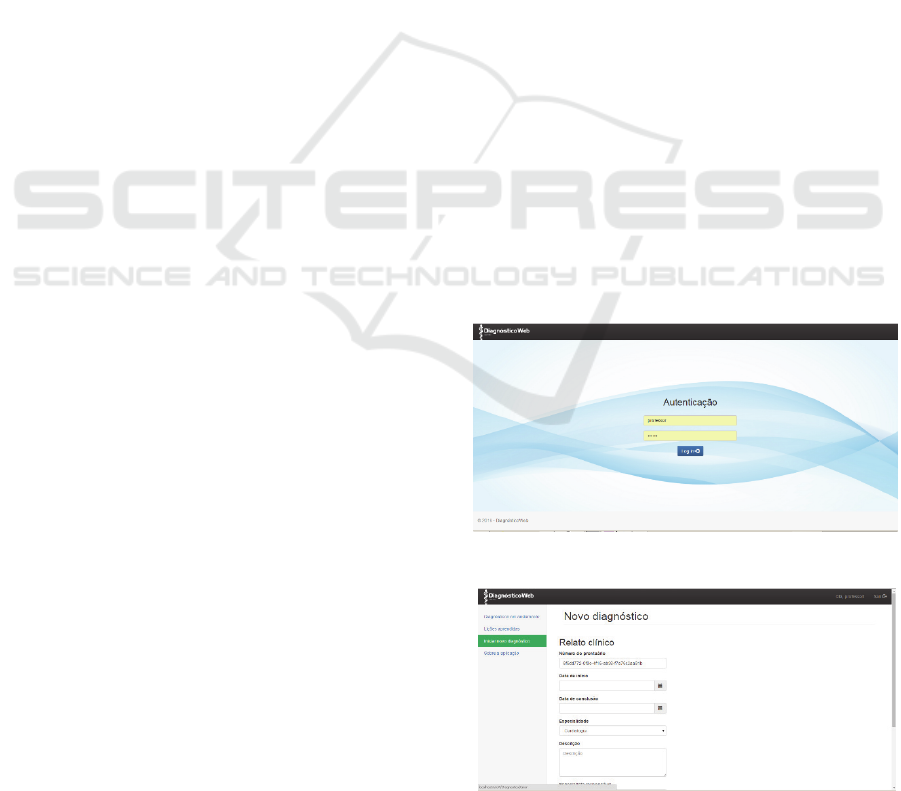

The authentication form is represented in Figure

2. All the system is Web based and the users must

have been added to GoldenAccess System

previously. There are two users’ types: the first is

instructor (with administrator powers) and the

second user type is student. The instructor can add

news cases for analysis by selecting (small) groups

of students to learn and to interact on each study

case in the collective intelligence phase (Figure 3).

The instructor plays the role of mediator in the

construction of collective knowledge. He or she

selects all cases to be studied by the groups of

students and monitors all stages throughout the

process. The student leader has the specialist

function responsible for the case study. She or he

will examine the case of information submitted by

the instructor and will be the first to submit an

Figure 2: Authentication form.

Figure 3: News cases for analysis.

Anaís: A Conceptual Framework for Blended Active Learning in Healthcare

203

assessment of the case study. For this, one could use

sources of external expertise (e.g. PubMed) and

internal (based on lessons learned). The other

students will participate in the collective intelligence

step and will have the role of assistant experts,

sharing knowledge and discussing the solution to the

case study.

The anamnesis form is represented in Figure 4.

The student leader will add all the patient

information into the system using anamnesis

processes. The anamnesis form is adapts according

to each specialty. Here, we implemented the

anamnesis forms for cardiology and ophthalmology.

Figure 4: News cases for analysis.

Figure 5 presents a form to help tacit-to-explicit

(externalization) and explicit-to-tacit

(internalization) knowledge conversion. In this step,

the student leader user will add all the evidences

(laboratory tests, related papers, images etc.) about

the case study. The user can also look for paper in

the PubMed and in the Learned Lessons databases,

appended to the case study.

At the end of this stage, a student group may

present a preliminary diagnosis for the case study,

which will be submitted to the analysis of other

students participating in the learning process.

Figure 5: Tacit-to-Explicit knowledge conversion forms.

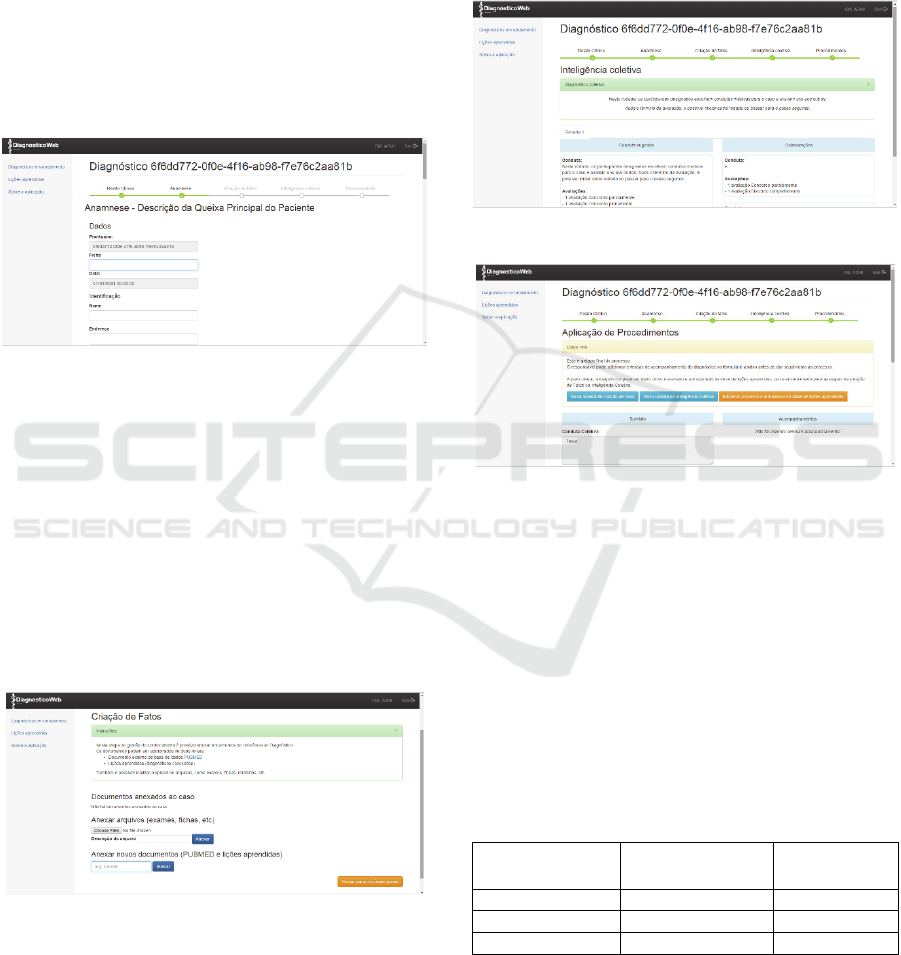

In the Decision Strategy step, helped by the

forms illustrated in Figure 6, for each study case, all

student groups share knowledge about the case being

studied through collective intelligence. This phase is

similar to a web forum, but convergence of all

answers is facilitated by the Delph Methodology

(Hsu and Sandford, 2007). When answer

convergence is attained, a collective diagnosis is

said to have been reached. The student leader will

then produce new evidences or create a new protocol

for saving in the Learned Lessons database (Figure

7).

Figure 6: Decision Strategy forms.

Figure 7: Learned Lessons database.

6 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

This section offers statistics, graphics and

discussions on the research results for the statements

A, B and C of section 4.

We used an ordinal scale that is non-parametric

and independent of the answers to questions A, B

and C. We used the Mann-Whitney test, with

confidence level 95% and alternative no equal. The

results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Mann-Whitney test results.

Questions Median

Mann-

Whitney (U)

A 4 (Equals) 0,6627

B 4 (Equals) 1,0000

C 4 (Equals) 0,4965

We wanted to know whether experts and

students of medicine believes that the Anaís

conceptual framework can be used as an AL tool for

professional training of specialist physicians. The

Mann-Whitney tests showed that alternative

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

204

hypotheses were refused (results should be

approximately the same). This shows that specialists

and students have the same positive opinion about

Anaís.

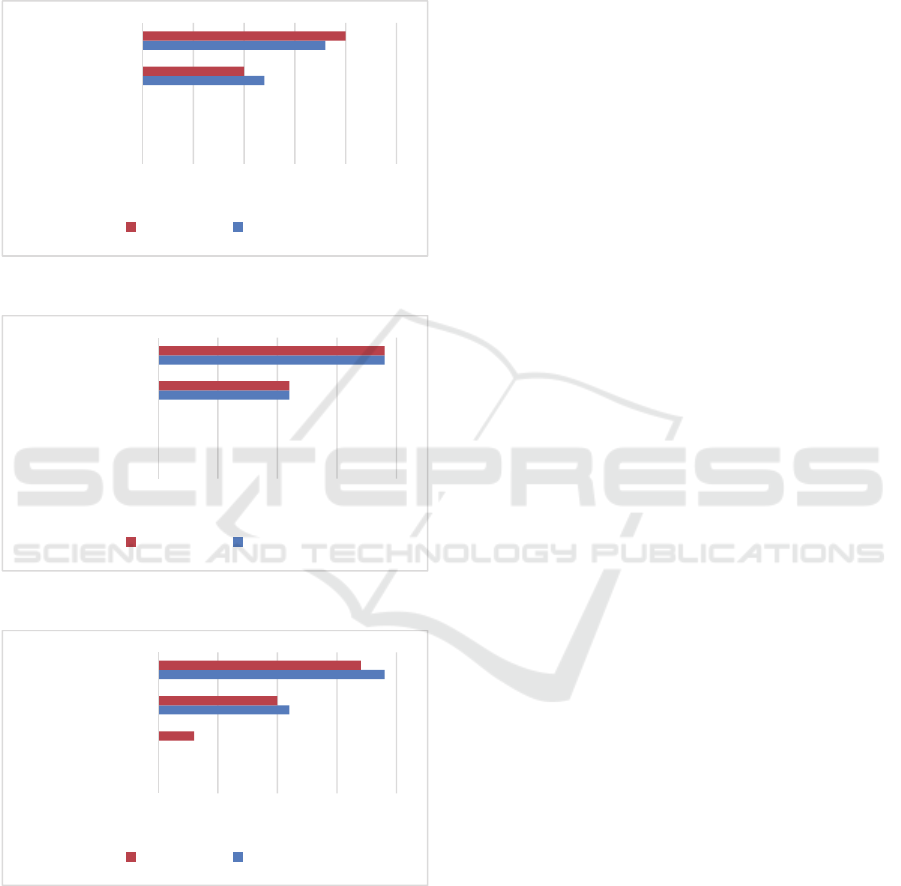

The results of the experiment in graphical form

are shown in Figures 8, 9 and 10.

Figure 8: Question A answers.

Figure 9: Question B answers.

Figure 10: Question C answers.

From Figure 8, “strongly agree” with statement

A is 63.34% (18 students and 20 specialists) while

33.66% “agree” (12 students and 10 specialists) - we

can thus say that 100% of the respondents agree that

the Anaís conceptual framework can be used as an

AL tool for professional training of specialist

physicians.

Equivalent conclusion can be drawn from the

graph in Figure 9 concerning statement B: 100% of

the users are satisfied with the Anaís conceptual

framework and could identify many effective

contributions to healthcare (63.34% - corresponding

to 19 students and 19 specialists who strongly agree,

and 33.66% - 11 students and 11 specialists who

agree with the statement).

Figure 10 shows that 60% (19 students and 17

specialists) strongly agree, 21% agree and 15% (3

specialists) disagree with statement C when they

ponder whether the model is useful and would invest

in its evolution. We believe that these answers are

biased by the time spent by specialists in equivalent

research. Sometimes specialists have their own

research on equivalent topics and students are more

interested in completing subject requirements

quickly.

Results from statistical tests, and also with the

descriptive data analysis, indicate that, in the opinion

of the specialists and the students, Anaís offers a

contribution to the area of healthcare studies and it

will bring benefits to learning as a BAL tool for

professional training of specialist physicians.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Anaís was proposed originally (Santos, Moura and

Araújo, 2015) to apply knowledge management

principles of tacit-to-explicit-to-tacit knowledge in

learning experiences. This research reported in this

paper aimed at eliciting opinions of specialists and

students in the healthcare area regarding the Anaís

conceptual framework as an effective BAL tool for

professional training of specialist physicians.

For that, 60 persons (30 health professionals and

30 students of medicine) were interviewed. They

used the Anaís conceptual framework based system

in a blended active learning scenario, and answered

a questionnaire to assess whether they thought the

proposed framework was valid BAL tool for

professional training of physicians. Preliminary

validation results are promising.

As for future work, we will concentrate on

further evaluating the BAL tool and on studying of

other cases with more specialists and students for

extended validations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is being carried out with support from the

0

0

12

18

0

0

10

20

0 5 10 15 20 25

Stronglydisagree

Disagree

Agree

Stronglyagree

Specialists Students

0

0

11

19

0

0

11

19

0 5 10 15 20

Stronglydisagree

Disagree

Agree

Stronglyagree

Specialists Students

0

0

11

19

0

3

10

17

0 5 10 15 20

Stronglydisagree

Disagree

Agree

Stronglyagree

Specialists Students

Anaís: A Conceptual Framework for Blended Active Learning in Healthcare

205

Brazilian Agency for the Improvement of Higher

Education Personnel (CAPES).

REFERENCES

Arano-Ocuaman, J., 2010., Differences in student

knowledge and perception of learning experiences

among non-traditional students in blended and face-

to-face classroom delivery. University of Missouri—

Saint Louis, USA.

Barros, M, Moura, A, Borgman, L., Terton, U.:Blended

Learning in Multi-disciplinary Classrooms -

Experiments in a Lecture about Numerical Analysis.

CSEDU (2) 2015: 196-204.

Bersin, J., 2004., The Blended Learning Book:

BestPractices, Proven Methodologies, and Lessons

Learned. John Wiley & Sons.

Bonwell, C., & Eison, J. 1991. Active learning: Creating

excitement in the classroom (ASHE-ERIC Higher

Education Report No. 1). Washington, DC: George

Washington University. Abstract online at

http://www.ed.gov/databases/ERIC_Digests/ed340272

.html.

Cayley WE. 2011. Effective clinical education: strategies

for teaching medical students and residents in the

office. WMJ. 2011;110:178–1.c.

CSEDU 2011, Proceedings of International Conference

on Computer Supported Education [online]. [Accessed

15 October 2014]. Available from:

http://pubs.iids.org/index.php/publications/show/1814.

De Jong, N. et. al. 2014. Blended learning in health

education: three case studies.Perspect Med Educ

3:278–288. DOI 10.1007/s40037-014-0108-1.

Drysdale, J.S., Graham, C.R., Spring, K.J., and Halverson,

L.R., 2013., An analysis of research trends in

dissertations and theses studying blended learning.

Internet and Higher Education, 17., pp. 90-100.

ElDin, Y. K. Z. 2014. Implementing Interactive Nursing

Administrationlectures and identifying its influence on

students’ learning gains. Journal of Nursing Education

and Practice. Vol. 4, No. 5.

Farias, P. A. M. de, et al. 2015. Active Learning in Health

Education: Historic Background and Applications.

Revista brasileira de educação médica.

Hsu, C., Sandford, B. A. 2007. The Delphi Technique:

Making Sense of Consensus. Practical Assessment,

Research & Evaluation. Vol 12, No 10.

Mitre, S. M. et. al. 2008. Active teaching-learning

methodologies in health education: current debates.

Ciênc. saúde coletiva vol.13 suppl.2 Rio de Janeiro

Dec.

Moore, J. 2005. Is Higher Education Ready for

Transformative Learning? A Question Explored in the

Study of Sustainability. Journal of Transformative

Education. Vol. 3: 76-91.

Mubuuke, A. G. Louw, A. J. N. and Schalkwyk, S. V.

2016. Utilizing students’ experiences and opinions of

feedback during problem based learning tutorials to

develop a facilitator feedback guide: an exploratory

qualitative study. BMC Medical Education.16:6. DOI

10.1186/s12909-015-0507-y.

Nilsson, M. S. et. al. 2010. Pedagogical strategies used in

clinical medical education: an observational study.

BMC Medical Education.

Nonaka, I. Takeuchi, H.. The Knowledge-Creating

Company: How Japanese Companies Create the

Dynamics of Innovation. Oxford University Press,

1995.

O’Sullivan DW and Copper CL. Evaluating active

learning. 2003. A New Initiative for a General

Chemistry Curriculum. Journal of College Science

Teaching. 32(7): 448-52.

Parmelee, Dean X. DeStephen, D. Borges, Nicole J. 2009.

Medical Students’ Attitudes about Team-Based

Learning in a Pre-Clinical Curriculum. Med Educ

Online [serial online].14:1 doi;10.3885/

meo.2009.Res00280. Available from http://www.med-

ed-online.org.

Ramsden, P. 1984. The context of learning. In F. Marton,

D. Hounsell & N. Entwistle (Eds.) The experience of

learning (pp. 144-164). Edinburgh: Scottish Academic

Press.

Theexperience of learning (pp. 144-164). Edinburgh:

Scottish Academic Press.

Think Aloud. [Accessed 10 January 2016]. Available

from:http://www.nngroup.com/articles/thinking-aloud-

the-1-usability-tool/.

Santos A. A, Moura J. A, Araújo J. M. de. 2015.A

Conceptual Framework for Decision-making Support

in Uncertainty- and Risk-based Diagnosis of Rare

Clinical Cases by Specialist Physicians. Studies in

Health Technology and Informatics. Volume 216:

MEDINFO 2015: eHealth-enabled Health.

Souza, C. da S. Iglesias, A. G. Pazin-Filho, A. 2014. New

approaches to traditional learning – general aspects.

Medicina (Ribeirão Preto);47(3): 284-92.

Wang, Q. et. al. 2016. Developing an integrated

framework of problem-based learning and coaching

psychology for medical education: a participatory

research. BMC Medical Education. 16:2. DOI

10.1186/s12909-015-0516-x.

Williams, J. Chinn, S. J. 2009. Using Web 2.0 to Support

the Active Learning Experience. Journal of

Information Systems Education, Vol. 20.

Zaher, E. Ratnapalan, S. 2012. Practice-based small group

learning programs. Can Fam Physician;58:637-42.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

206