Detecting Thermal Emotional Profile

Yang Fu and Claude Frasson

University of Montreal, Department of Computer Science and Operations Research, Montreal, Canada

Keywords: Emotion Recognition, IAPS, Skin Temperature, Thermal Emotional Profile, Machine Learning, EEG, HMM

(Hidden Markov Model), Infrared Camera.

Abstract: Human can react emotionally to specific situations provoking some physiological changes that can be detected

using a variety of devices, facial expression, electrodermal activity, and EEG systems are among the efficient

devices which can assess the emotional reactions. However, emotions can trigger some small changes in blood

flow with an impact on skin temperature. In the present research we use EEG and a thermal camera to

determine the emotional profile of a user submitted to a set of emotional pictures. Six experiments were

performed to study the thermal reactions to emotions, and in each experiment, 80 selected standard stimuli

pictures of 20 various emotional profiles from IAPS (a database of emotional images) were displayed to

participants every three seconds. An infrared camera and EEG were used to capture both thermal pictures of

participants and their electrical brain activities. We used several area of the face to train a classifier for emotion

recognition using Machine Learning models. Results indicate that some specific areas are more significant

than others to show a change in temperature. These changes are also slower than with the EEG signal. Two

methods were used to train the HMM, one is training classifier per the participant self data (participant-

independent), another is training classifier based on all participants` thermal data (participant-dependent). The

result showed the later method brings more accuracy emotion recognition.

1 INTRODUCTION

Research in education, psychology, computational

linguistics, and artificial intelligence acknowledge

that emotions have an effect on learning (Heraz et al,

2007). Many works in that field focus on identifying

learners’ emotions as they interact with computer

systems such as Intelligent Tutoring Systems

(Chaffar et al, 2009) or educational games (Derbali et

al, 2012).

Unfortunately, many of these types of systems

only focus on external behavior like face analysis,

vocal tones and gesture recognition. Most of the time,

psychological methods are used to collect real-time

sensing data. Despite the advances in these methods,

it is still a challenging problem. The effective

emotional state and its assessment lack precision. In

addition, these methods are not applicable in the case

of disabled, taciturn and impassive learners. Today,

researches are directed toward a multi-model system

that can automatically extract physiological signals

changes in addition to vocal, facial or posture changes.

All those features can be combined to detect and

assess emotions.

1.1 Assessing Emotions

To properly interact with the learner, the emotion data

collection methods have evolved from self report

(Anderson, 2001) to facial expression analysis

(Nkambou, 2004), to body posture and gestures

interpretations (Ahn et al, 2007), and to biofeedback

measurements (Heraz et al, 2007, 2009). To increase

the prediction of the emotional and cognitive learner

states, the approaches of combining different kinds of

information collection channels were applied

(Kapoor et al, 2005). Regarding biofeedback

measurement, researches showed that the

Electroencephalograms (EEG) is one of the most

reliable and accurate physiological signal to monitor

the brain activities (Heraz et al, 2007). However, the

wearable EEG devices, such as Q sensor (worn on

wrist), EPOC Neuroheadset (worn on head), or

SomaxisMyoLink (worn on body), also limit the

user’s movement. It will be more convenient if there

is a way to measure emotions noninvasively. In our

research, our goal is to see the relation between the

changes of skin temperature and emotions.

142

Fu, Y. and Frasson, C.

Detecting Thermal Emotional Profile.

DOI: 10.5220/0006007901420151

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems (PhyCS 2016), pages 142-151

ISBN: 978-989-758-197-7

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

1.2 A New Way to Measure Emotions

Noninvasively

During the past half century, psychologists have

discovered and studied the relationship between skin

temperature and emotion changes (Baker and Tayor,

1954). They have indicated that the skin temperature

is getting lower because of the production of a

constriction of the arterioles when the participants are

under a stressful situation. By testing 27 participants

with 4 negative and 4 positive stimuli, Vos P et al

(2012) found that the skin temperature is higher for

expressing low intensity emotions negative emotions.

Kuraoka and

Nakamura

(2010) measured the nasal

region temperature changes studying emotion in

macaque monkeys. They found temperature

decreased when the monkeys were facing negative

situations. More interestingly, the experiment in the

paper (Ioannou et al. 2013) showed that when a child

felt guilty after breaking a toy, his nose tip cooled off

with more purple color (third picture); and after he

was soothed, the thermal color turned more orange

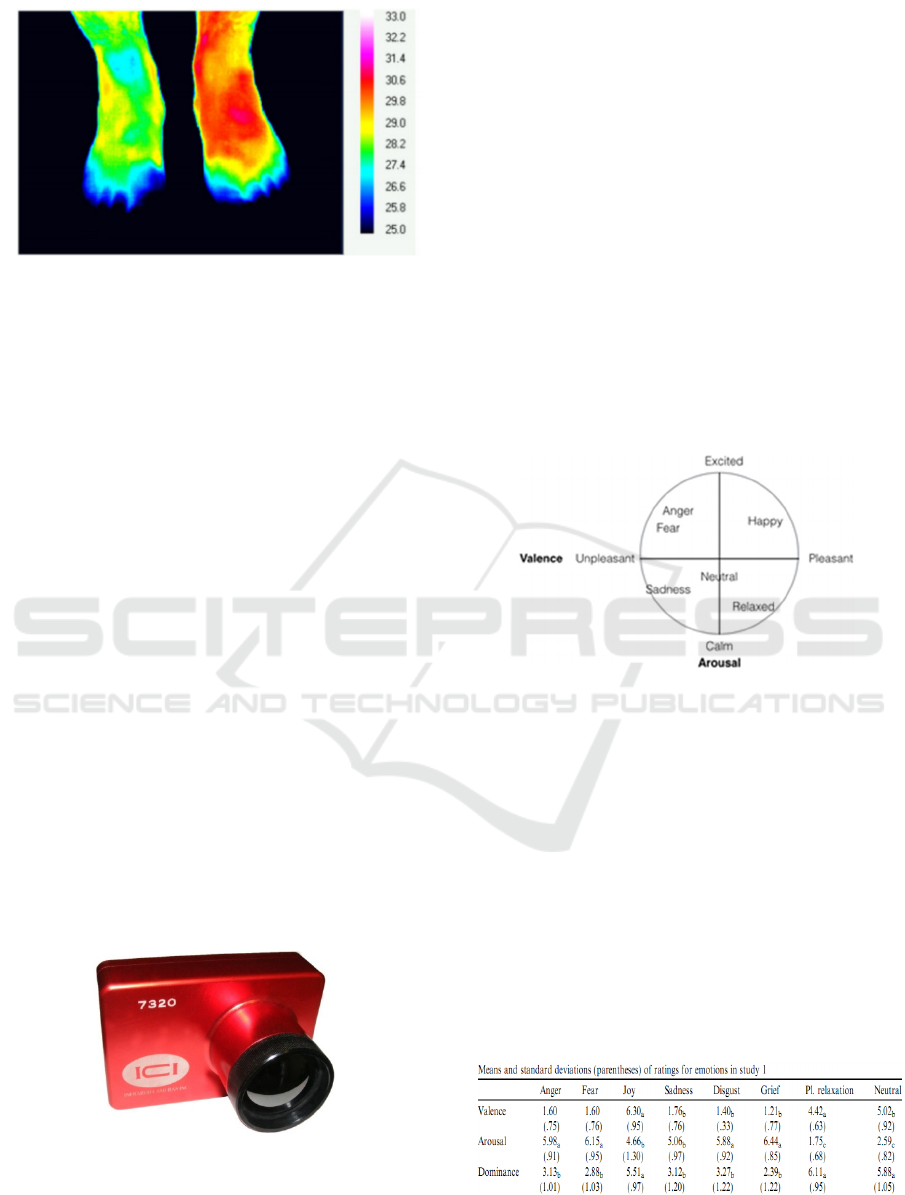

indicating his nose wormed (fifth picture) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Five pictures of a child showing the temperature

change of the nasal tip.

In this paper we present an exploratory study of

using thermal camera to detect and assess emotions.

After looking at the functionalities of thermal camera

and their use in the industry, we present the features

of Electroencephalograms devices (EEG), a well

known method for assessing emotions, mental

engagement and workload. Then, we present the

experiments realized with a set of emotional stimuli

and the two devices. We compare the measures

obtained with the two devices to validate thermal

assessments.

2 THERMAL CAMERA

FUNCTIONALITIES

Infrared thermography is a powerful technique for

non-destructive and non-invasive investigation. It has

been applied in building leakage detection (Titman,

2001), in medicine area (Jones, 1998), and even in

accident rescue (Doherty et al., 2007). Because of its

non-invasive and non-destructive nature, the thermal

detection can be rapidly completed, with slight access

efforts and costs. The visibility of the output also can

be interpreted immediately by a skilled practitioner

(Titman, 2001)

.

2.1 Building Leaks

Temperature factors were used to detect where and

how energy leaks from a building’s envelope and

substantiate proposals. The source of the problems

can be revealed accurately and detailed by using IR

thermography. The problems may include improperly

installed or damaged insulation, thermal bridges, air

leakage, moisture damages or cracks in concretes. For

instance, a thermal picture can show a missing

insulation as a light colored patch with distinct edges

(Balaras, 2002).

Figure 2: Thermograph of an interior roof surface with

missing insulation (Balaras et al. 2002).

2.2 Thermal Camera in Medicine

Measuring body temperature is one of the traditional

diagnostic methods in medicine, besides, it is also

applied to measure the outcome of clinical trials.

In recent decades, as a non-invasive and painless

method, thermal imaging technique has been widely

applied to various fields of diagnostic, such as to find

the sites of fractures and inflammations, to recognize

the degree of burn, to detect breast cancer and to

determine the type of skin cancer tumors (Ogorevc et

al., 2015).As Ring et al. (2012) mentioned in their

research, the skin temperature can indicate the

existence of inflammation in underlying tissue

(Figure 3), osteoarthritis, soft tissue rheumatism, and

complex regional pain syndrome (CPRS). A

temperature difference (>= 1 °C) between the

affected and the non-affected limb is one of the

diagnostic criteria of CPRS (Wilson et al. 1996).

Detecting Thermal Emotional Profile

143

Figure 3: Chronic inflammation of the forefoot following a

sport injury (Ring, 2012).

Studies showed that infrared imaging is also a

powerful tool for clinical testing. Devereaux et al.

(1985) used infrared thermography to quantify joint

inflammation and to assess patients’ response to

therapy of rheumatoid arthritis. By following patients

over 12 months, the researchers found that there are

significant correlations for thermography with other

parameters of disease activity. In recent years, per the

study of Spalding et al. (2008), it was proved that

three-dimensional measures and thermal imaging are

able to measure a high coincidence between high

temperature and swelling of figure joints.

2.3 Using Infrared Camera for Emotion

Detection

2.3.1 Infrared Camera

In our study, we used an infrared camera (ICI 7320)

(Figure 4

)to capture real time thermal images and

provide real time radiometric data streams to hard

device or portable device. The camera is able to give

sensitive and accurate thermal data of arrange of -

20°C to 100°C. Comparing with EEG, because of the

camera’s non-invasive feature, it is easier to set up

and configure.

Figure 4: ICI 7320 Infrared Camera.

2.3.2 Iaps

To know which emotions should be detected we used

a set of emotional pictures as stimuli materials which

have been categorized according to specific emotions.

The Centre for the Study of Emotion and Attention

(CSEA) of the University of Florida developed two

large sets of affective stimuli, IAPS (International

Affective Picture System) and IADS (the

international Affective Digitalized Sound system), to

provide standard materials for emotion and attention

related studies. Based on Osgood (Osgood et al. 1962)

seminal work, IAPS assessed the emotions from three

dimensions: affective valence, arousal and

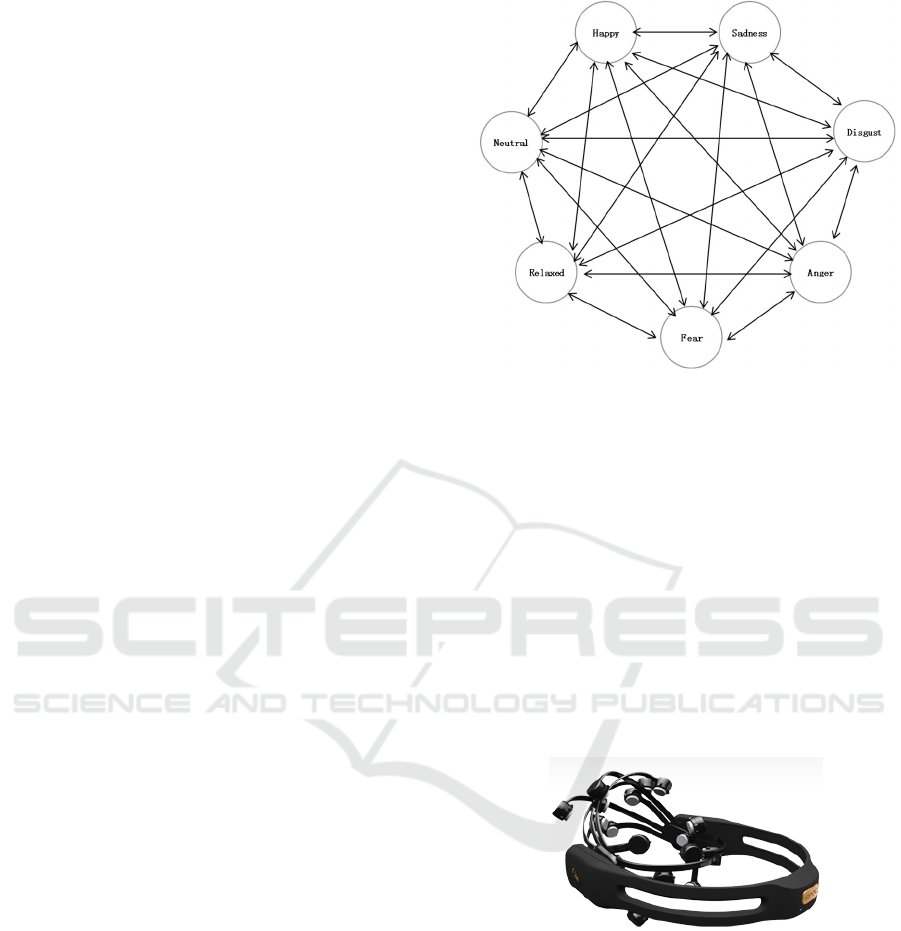

dominance. In this research, the arousal-valence

model (Figure 5) was used to represent the emotions.

Valence ranges from pleasant to unpleasant and

arousal ranges from calm to excited. Dominance,

which is also called control, is a less strongly-related

dimension. In our experiments, we selected 80 IAPS

pictures from 20 various picture sets for presenting to

participants and measuring their emotional reactions.

Figure 5: Arousal-valence Model.

Emotions considered were: neutral, happy,

sadness, anger, fear, disgust, sadness. To measure

them according to arousal and valence dimensions,

we used the means and standard deviations

(parentheses) of the rating emotion table (Figure 6)

from Panayiotou (2008) research as a standard base

for further machine learning.

Human skin temperature is the product of heat

dissipated from the vessels and organs within the

body, and the effect of environmental factors on heat

loss or gain. To facilitate the detection of emotions by

thermal variations we will focus on five area of the

face, including forehead, nose, mouth, left cheek

and right cheek.

Figure 6: Means and standard deviations (parentheses) of

ratings for emotions (Panayiotou, 2008).

PhyCS 2016 - 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems

144

Considering that the temperature changes may

require time to display on participants skin, every

picture was displayed three seconds. Meanwhile, to

figure out how the skin temperature is back to a

‘neutral’ status, a non-stimuli picture shows in

between every two IAPS pictures.

The emotional profile, which depends on each

participant, will be based on two parameters: 1) the

rapidity of the thermal changes, and 2) the

temperature change intensity.

2.3.3 Hidden Markov Models

Six students were invited to participate into this study

and they were asked to watch the eighty slide-

showing pictures without any disruption. Thermal

photos were taken every three seconds during the

picture-displaying period. Then the thermal changes

on the five areas of their face (forehead, nose, mouth,

left cheek and right cheek) were trained and classified

with a Hidden Markov Model, in order to obtain the

thermal emotional profiles.

Hidden Markov Models (HMM) are widely used

to find out the joint probability of a collection of

hidden variables and observed variables. It is defined

by a tuple λ=(n, m, A, π, B), where n indicates the

number of hidden states, m indicates the number of

observable states, A is the state transition probability,

B is the emission probability density function of each

state, and π is the initial state probability. In this

research, recognizing emotion from a series of

thermal data over the time is a typical modeling

problem which can take advantage of be resolved by

HMM.

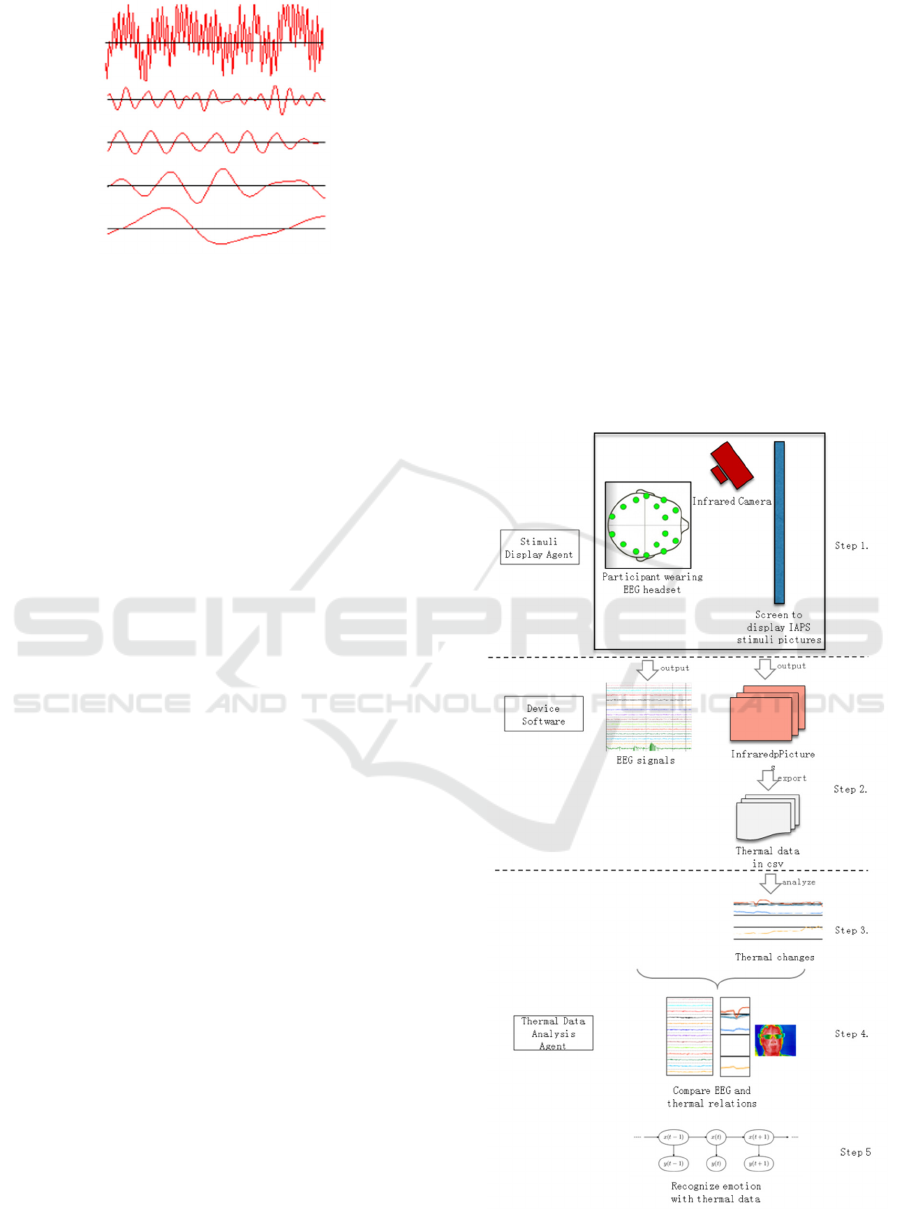

As an emotion state can transfer to any other states,

the state-transition topology of the emotion

recognition model is an ergodic topology (Figure 7).

Then we train the maximum likelihood classifier

using the Baum-Welch algorithm. According to the

classifiers, the hidden states – emotions (neutral,

happy, sadness, disgust, anger, fear, relaxed) can be

computed per the observed states (turn wormer (1),

/colder (2), or no change (0) on nose, on forehead, etc.)

- the thermal change states. Two training methods

were used in our study: one is to train the classifier

with a participant’s self previous data, which was

named as participant-independent training. Another

is to train the classifier based on all other participants’

data, named as participant-dependent method.

Figure 7: Training classifiers using Hidden Markov Model.

3 USING EEG TO MEASURE

EMOTIONS

3.1 Emotiv Classification of Emotions

In many recent researches, EEG (Figure 8) has been

applied to recognize emotions. We also took EEG as

comparison reference to analyze the rapidity and

intensity of thermal signals. Thus EEG signal was

captured at the same time when the participants were

watching the experiment pictures and when the

thermal pictures were recorded.

Figure 8: Emotiv EPOC headset.

EEG detects the electrical signals released by the

brain through a series of electrodes placed. The

brainwaves were categorized into 6 different

frequency bands which named as delta, theta, alpha,

beta1, beta 2 and beta 3 waves (Figure 9.). Two of

them, the alpha (8-12Hz) and beta (12-30Hz) were

concentrated in our research, since alpha waves are

the main indicator for an alert and beta signals are

related to the active state of mind (Bos et al. 2006).

Detecting Thermal Emotional Profile

145

Figure 9: A raw EEG sample and its filtered component

frequencies. Respectively (from the top): Beta, Alpha,

Theta and Delta Brainwaves (Heraz et al. 2009).

3.2 Correlation between Two Measure

Methods

For years, EEG has been used in many researches to

recognize emotions. Murugappan et al. (2009)

combined spatial filtering and wavelet transform to

classify emotions (happy, surprise, fear, disgust, and

neutral). Liu et al. (2010) implemented a real-time

algorithm to recognize six emotions, including fear,

frustrated, sadness, happy, pleasant and satisfied, and

achieved 90% classification accuracy for

distinguishing joy, anger, sadness and pleasure. EEG

was also applied in monitory drivers’ emotional

behavior and help them to adjust their negative

emotions to keep driving safely (Frasson et al. 2014).

Based on the EEG emotion recognition methods

and algorithms, it is more efficient for us to apply the

thermal technique into emotion detection area. We

can also use the HMM or other proved model to

perform classification and detect emotion changes.

The only questions to consider are which thermal

signals to capture, how to tailor the classifier training

model to fit the thermal data processing approach, and

how to check the accuracy of emotion recognition

with thermal signal.

Thus, in our research, the EEG emotion detection

methods were used as important inputs and reference

for the study of applying thermal signal on emotion

reorganization.

4 EXPERIMENT

4.1 Experiment Overview

4.1.1 Experiment Method

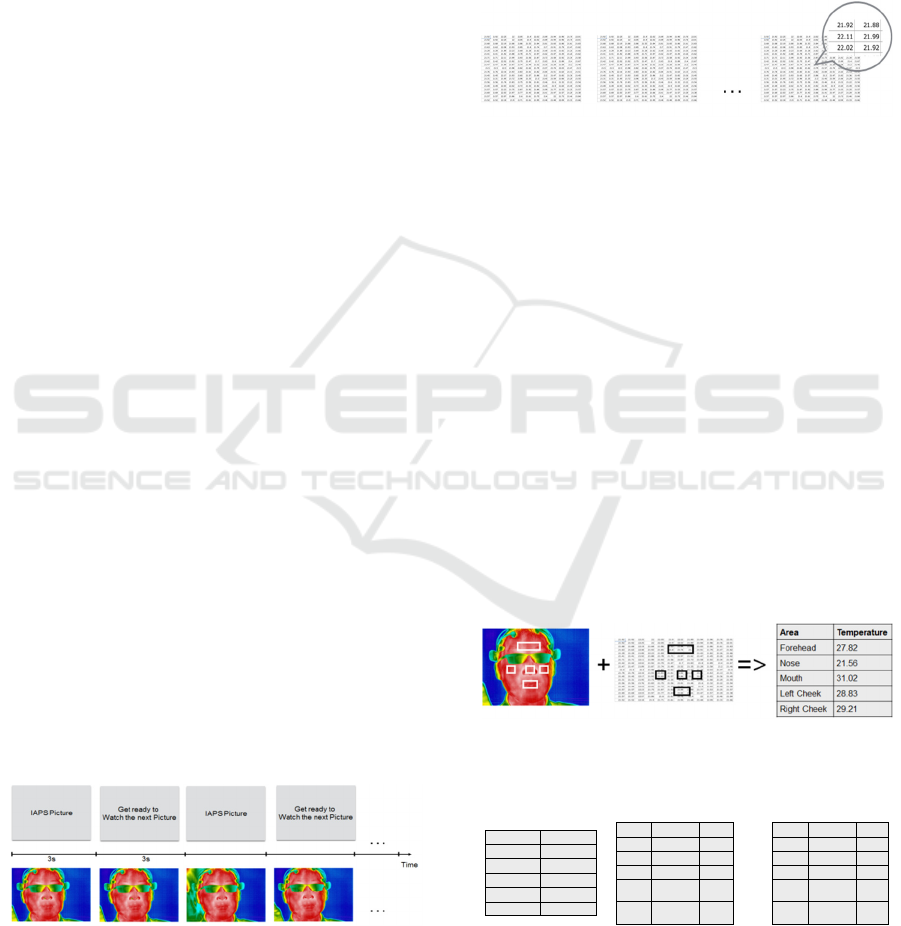

As shown in Figure 10, the participants were invited

to watch a series of IAPS stimuli pictures. During the

experiment, an Emotiv EPOC headset (Figure 8) and

an infrared camera (ICI 7320, Figure 4) were used to

respectively capture the real-time

electroencephalogram (EEG) signal and the thermal

pictures of the participants’ faces. After recording

both EEG and thermal pictures, we used the ICI

camera software to export the 640*480 digital

temperature matrix, which means totally 300k

temperature data, in csv format for each infrared

picture. To deal with the numerous thermal data, a

data analysis agent was implemented to detect face

areas, calculate average temperatures, and identify

thermal changes. By comparing the EEG and thermal

changes, we analyzed the thermal emotional profiles

according to rapidity and intensity parameters. The

details of the approach are presented in the next

subsection.

Figure 10: Experiment Method.

PhyCS 2016 - 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems

146

4.1.2 Experiment Material Selection

The International Affective Picture System (IAPS)

provides the rating of a large set of emotionally-

evocative color photographs across a wide range of

semantic categories. In each picture set (totally 20

picture sets), 60 different IAPS pictures are varied in

valence and arousal ranges. To measure participant’s

emotional reactions distinguishably, we selected 4

various pictures in each picture set and displayed

them 3 seconds each, which means that80 IAPS

pictures were selected. Meanwhile, to measure the

thermal emotional changes when the participant is in

neutral state, a preparation picture writing “Get ready

to watch the next picture” appeared for three seconds

before displaying the next IAPS picture.

4.2 Experiment Steps

The methodology of the experiment process is

decomposed into five steps indicated below. Two

agents Stimuli Display Agent and Thermal Data

Analysis Agent) are co-working with EEG and ICI

camera software in experiments. The Stimuli Display

Agent was designed to associate the experiment to

record participant info, experiment info and every

pictures displaying time, etc. About Thermal Data

Analysis Agent, it was developed to read thermal

pictures, calculate face five areas temperature, and

analyze thermal changes.

Step 1. Participants View Stimuli Pictures, and

Devices Record EEG Data and Thermal

Pictures. Six experiments were performed one by

one with different participants of similar age and

different gender. We helped every participant to wear

the EEG headset and positioned the IR camera in

front of him/her. After the devices were set properly,

the participant was invited to watch the pictures slide-

showed by the Stimuli Display Agent in a quiet

environment. In the meantime the pictures were

displaying, the EEG data were recorded in real time

and the thermal pictures were taken (refer to the

sample picture in Figure 11) every 3 seconds.

Figure 11: Step 1. The 80 stimuli pictures and 80

preparation-slides were presented each three seconds in

turn. At the same time, the ICI camera was taking thermal

photos every three seconds.

Step 2. Export Temperature Data for Every

Thermal Picture. As mentioned in the Experiment

Material Selection paragraph, in each experiment,

160 pictures were displayed to each participant and a

total of 160 thermal photo accordingly. Later the

thermal pictures were manually exported into related

160 cvs files (as IR Flash Software version 2.13.29.10

only supports exporting thermal matrix into csv file

one by one) (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Using IR Flash Software to export cvs file for

every thermal photo to get 640*480 temperature-matrix.

Step 3. Calculate the Mean Temperatures on Five

Face Areas and Analyze Thermal Changes. The

face location was detected manually and five areas

were focused for further analyzing thermal changes

(Figure 13). Considering that every thermal picture

can generate a 640 * 480 temperature data matrix, the

data volume of 160 thermal pictures reaches almost

50 millions data. To process the data efficiently, an

initial analysis of calculating area average

temperature were performed and the mean values

were recorded instead of saving the huge amount of

raw data into database, performed by the Thermal

Data Analysis Agent. Then the thermal state changes

(Figure 14) were identified. Please note that we

focused more on the temperature changes, not the

absolute temperature value since every human has

different thermal activity, even when they are in the

same environment.

Figure 13: For each thermal photo, find five-areas (forehead,

nose, mouth, left cheek and right cheek) locations, and then

calculate the five-area mean temperatures.

Figure 14: Comparison and extraction features of the

thermal photo series.

Area Temperature

Forehead 27.82

Nose 21.56

Mouth 31.02

Left Cheek 28.83

Right Cheek 29.21

Area Temperature Change

Forehead 27.98 ↑

Nose 20.06 ↓

Mouth 31.62 ↑

Left

Cheek

27.98 ↓

Right

Cheek

28.65 ↓

Area T emperature Change

Forehead 28.02 ↑

Nose 20.56 ↑

Mouth 30.72 -

Left

Cheek

27.76 ↓

Right

Cheek

29.67 ↑

…

The 1

st

Thermal

Picture

The 2

nd

Thermal

Picture

The N

th

Thermal

Picture

Detecting Thermal Emotional Profile

147

Step 4. Compare EGG Emotional Profiles with

Thermal Emotional Profiles. In this step, both EEG

data and thermal changes were compared to analyze

the rapidity and intensity of thermal emotional

profiles (Figure 15). For the EEG data, the beta/alpha

ratio (Fp1 and Fp2) were set as an indicator of the

arousal state, and alpha activities (F3, F4) was used

to recognize valence state (Bos, 2006). Then we use

the thermal change produced in previous step to

compare with the EEG arousal/valence states to

figure out if thermal detection refers to the same

emotional state measured by the EEG.

Figure 15: EEG and Thermal Data Comparison.

Step 5. In this step, we applied Hidden Markov

Model on emotion recognition using thermal data. As

mentioned in subsection 2.3.3,we trained the emotion

classifiers based on participant itself data (named as

participant-independent model) or based on other

participants’ data (named as participant-dependent

model).

For the first model, only current participant’s

thermal signals were taken into account. The thermal

data of the first 60 IAPS pictures and 60 preparation

pictures were used as inputs to train the classifier for

a participant, then the classifier was used to recognize

the emotions when he/she was watching the rest of 20

pictures.

For the second model, the participant-dependent

model, in order to recognize a participant’s emotion

when he/she was watching the stimuli picture, the

classifiers were trained based on the other five

participants’ thermal data, As the training base for the

second model is larger than the first model,

theoretically, the emotion recognition accuracy of the

second model will be better than the first one. In the

next section, the experiment result shows that the

inference is correct.

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

5.1 Thermal Profiles on Face

By assessing all the six experiment results, we found

that generally the nose temperature is lower than

cheek temperature, and normally the left cheek is

cooler than the right cheek which is the same as the

finding of Rimm-Kaufman et al (1996).Figure 16

shows the sub segments of the 2

nd

and 3

rd

experiment.

X indicated the pictures number that the participant

watched (0 refers to the preparation picture) and Y

indicates the temperature.

Figure 16: Two thermal signal charts of the 2

nd

and the 3

rd

experiment, showed that left cheek is cooler than the right.

5.2 Thermal Emotional Profiles:

Rapidity and Intensity

Per the biological theory, the skin temperature

changes because of the stimulation of nervous system,

oxygen to the muscles, heart beat and blood pressure

(Doucleff, 2013). So the skin thermal signal must

appear slower than the brain signals. Then two

questions need us to find answers: How long the

thermal change can reflect on participant’s skin? And

what are the thermal intensities reflecting to different

stimuli materials. In this section, we compare EEG

and thermal data to analyze the emotional profiles

from two dimensions: rapidity and intensity (Figure

17).

37

37.5

38

38.5

39

39.5

40

40.5

9414 0 9469 0 9941 0 1410 0

A segment of 2

nd

Experiment

Forehead

Nose

Mouth

LeftCheek

RightCheek

36.5

37

37.5

38

38.5

39

39.5

9414 0 9469 0 9941 0 1410 0

A segment of 3

rd

Experiment

Forehead

Nose

Mouth

LeftCheek

RightCheek

PhyCS 2016 - 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems

148

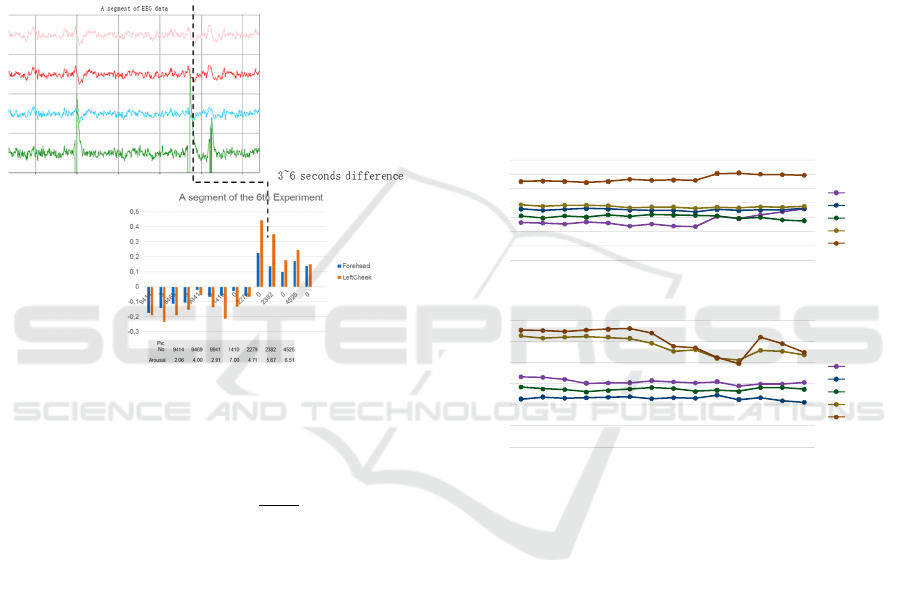

Figure 17: A similar while slower thermal arousal segment

comparing with EEG arousal.

We filtered EEG data, and then used FC6 for

getting the arousal levels and F3/F4 channel for

getting the valence levels (Liu et al. 2010). By

comparing the EEG channel signals with thermal

changes which calculated in the experiment step 3, we

found that around 60% similar thermal arousals on

forehead and left cheek were shown 3 to 6 seconds

after the EEG arousal. In terms of intensity, the

temperature increase were normally within a range of

0.1°C to 0.5°C, and temperature decrease in a smaller

range of 0.05 to 0.3°C, which means the skin

temperature is easier to increase than to decrease.

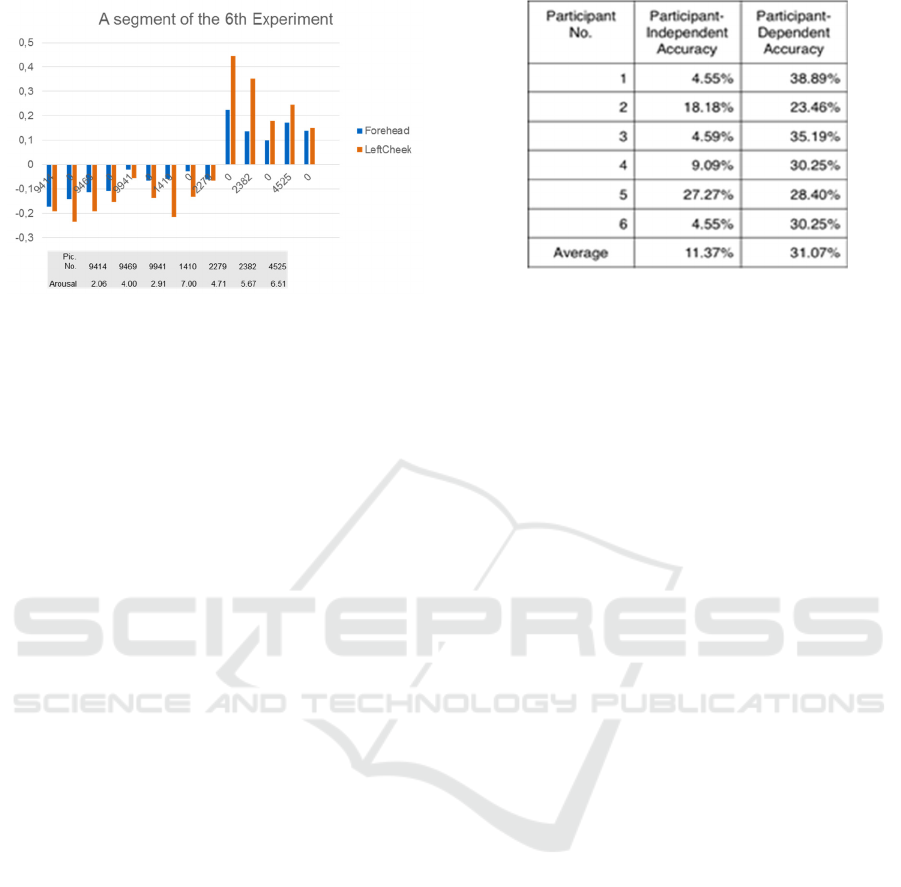

5.3 Thermal Emotion Recognition

using HMM

As mentioned in the experiment approach section, the

emotion recognition was conducted using participant-

independent and participant-dependent method. The

method of training classifiers is based on the

participant’s first 60 pictures and 60 preparation

slides, and then computing the probabilities and

recognize emotions for the rest of 40

pictures/preparation-slides, is called participant-

independent. For the participant-dependent method,

as the name signifies, one participant’s emotion

likelihood depends on the other participants’

classifications, which means that the classifier

training was based on totally 800 (=160*5) thermal

samples. The results in Figure 18 show that we

achieved higher accuracies with participant-

dependent model, which meets our inference.

Figure 18: The participant-independent and participant-

dependent accuracy table.

From an overall point of view, there are

possibilities to improve the emotion recognition

accuracies to higher rate. The solutions could be to

perform more experiments, to display more IAPS

pictures to train the model, and to replace current

manually indicated five-area locations by detecting

automatically the five-area locations subject to

change.

6 CONCLUSIONS

More experiments could be performed to improve the

HMM classifier training, to enhance the analysis

accuracy, and study the emotion profile differences

by gender or ages. Furthermore, the matching

learning algorithm used in this research could be

applied to recognize the emotion profiles on the other

normative emotional stimuli sets, such as IADS2 (the

International Affective digitized Sounds). More data

analysis can be applied to find which part(s) of skin

temperature can provide more accurate emotion

recognition. Meanwhile, as manually locating faces

on thermal photo is unrealistic in high volume of data

analysis, an automatic face detection method should

be built out to improve the efficiency. Next target also

includes the improvement of our application, Thermal

Profile Analyzer to display both EEG and thermal

signals for replaying the experiment and showing

participant’s emotional analysis result.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research presented in this paper has been

supported by funding awarded by the Natural

Sciences and Engineering Research Council of

Canada (NSERC).

Detecting Thermal Emotional Profile

149

REFERENCES

Ahn, Hyung-il, Teeters, Alea, Wang, Andrew, Breazeal,

Cynthia, & Picard, Rosalind. (2007). Stoop to Conquer:

Posture and affect interact to influence computer users'

persistence, The 2nd International Conference on

Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction,

September 12-14, Lisbon, Portugal.

Anderson, James. (2001). Tailoring Assessment to Study

Student Learning Styles. In American Association for

Higher Education, (53) 7.

Baker, Lawrence M.; Taylor, William M. (1954). The

relationship under stress between changes in skin

temperature, electrical skin resistance, and pulse rate.

Journal of Experimental Psychology, Vol 48(5), Nov

1954, 361-366.

Balaras, C. A., &Argiriou, A. A. (2002). Infrared

thermography for building diagnostics. Energy and

buildings, 34(2), 171-183.

Bos, Danny Oude, (2006). EEG-based Emotion

Recognition, The Influence of Visual and Auditory

Stimuli. Department of Computer Science, University

of Twente.

Chaffar, Soumaya, Derbali, Lotfi, & Frasson Claude.

(2009). Towards Emotional Regulation in Intelligent

Tutoring Systems, AACE World Conference on E-

learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare&

Higher Education: E-LEARN 2009, Vancouver,

Canada.

Derbali, Lotfi& Frasson, Claude. (2012). Assessment of

Learners’ Motivation during Interactions with Serious

Games: a Study of some Motivational Strategies in

Food-Force. Advances in Human-Computer

Interaction - Special issue on User Assessment in

Serious Games and Technology-Enhanced Learning.

Volume 2012, January 2012. Article No. 5.

Devereaux, M. D., Parr, G. R., Thomas, D. P., &Hazleman,

B. L. (1985). Disease activity indexes in rheumatoid

arthritis; a prospective, comparative study with

thermography. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 44(7),

434-437.

Doherty, Patrick &Rudol, Piotr. (2007) A UAV Search and

Rescue Scenario with Human Body Detection and

Geolocalization, Volume 4830 of the series Lecture

Notes in Computer Science pp 1-13.

Doucleff, Michaeleen. (2013). Mapping Emotions On The

Body: Love Makes Us Warm All Over, Health News

From NPR, December 30, 2013.

Frasson, C., Brosseau, Pierre-Olivier, Thi Hong Dung Tran.

Virtual Environment for Monitoring Emotional

Behaviour in Driving. The 12th International

Conference On Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS 2014).

Honolulu, Hawaii. June 5-9, 2014.PDF.

Heraz, Alicia, Razaki, Ryad. & Frasson, Claude. (2007)

Using machine learning to predict learner emotional

state from brainwaves. 7th IEEE conference on

Advanced Learning Technologies: ICALT 2007,

Niigata, Japan, 2007.

Heraz, Alicia, Razaki, Ryad. & Frasson, Claude. (2009)

How Do Emotional Stimuli Influence the Learner's

Brain Activity? Tracking the brainwave frequency

bands Amplitudes. International Conference on Agents

and Artificial Intelligence. ICAART, Jan 2009. Porto,

Portugal.

Ioannou, Stephanos, Ebisch, Sjoerd, Aureli, Tiziana,

Bafunno, Daniela, Ioannides, Helene Alexi, Cardone,

Daniela, Manini, Barbara, Romani, Gian Luca, Gallese,

Vittorio, &Merla, Arcangelo. (2013) The Autonomic

Signature of Guilt in Children: A Thermal Infrared

Imaging Study. Published: November 19, 2013. DOI:

10.1371/journal.pone.0079440.

Jatupaiboon, Noppadon, Pan-ngum, Setha, &Israsena,

Pasin. (2013). Real-Time EEG-Based Happiness

Detection System, The Scientific World Journal, vol.

2013, Article ID 618649, 12 pages, 2013.

doi:10.1155/2013/618649.

Jones, B.F.(1998) A Reappraisal of the Use of Infrared

Thermal Image Analysis in Medicine, IEEE

TRANSACTIONS ON MEDICAL IMAGING, VOL. 17,

NO. 6, DECEMBER 1998, 1019-1027.

Kapoor, Ashish, Ahn, Hyungil, & Picard, Rosalind W.

(2005) Mixture of Gaussian Processes for Combining

Multiple Modalities, in Proceedings of Multiple

Classifier Systems, Eds. N. C. Oza, R. Polikar, J. Kittler,

and F. Roli, 6th International Workshop, MCS 2005,

June 2005, Seaside, CA, pp. 86-96.

Kuraoka, Koji,Nakamura, Katsuki. (2011) The use of nasal

skin temperature measurements in studying emotion in

macaque monkeys. Physiology & Behavior Volume 102,

Issues 3–4, 1 March 2011, Pages 347–355.

Lang, Peter J. (2008). International affective picture system

(IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction

manual. Technical Report A-8. University of Florida,

Gainesville, FL. Bradley, M.M., & Cuthbert, B.N.

(2008).

Liu, Y., Sourina, O., & Nguyen, M. K. (2010, October).

Real-time EEG-based human emotion recognition and

visualization. 2010 International Conference on

Cyberworlds (CW)(pp. 262-269). IEEE.

Murugappan, M., Nagarajan, R., &Yaacob, S. (2011).

Combining spatial filtering and wavelet transform for

classifying human emotions using EEG Signals.

Journal of Medical and Biological Engineering, 31(1),

45-51.

Nkambou, R.V. (2004). Facial expression analysis for

emotion recognition in ITS. In: ITS’2004 workshop on

Emotional Intelligence proceedings.

Ogorevc, J., Pušnik, I., Geršak, G., Bojkovski, J.,

&Drnovšek, J. (2015). Thermal imaging in medicine.

ZdravniškiVestnik, 84(11), 757-770.

Osgood, C.E. (1962). Studies on the generality of affective

meaning systems. American Psychologist, 17, 10-28.

Panayiotou, G. (2008). Emotional dimensions reflected in

ratings of affective scripts. Personality and Individual

Differences, 44(8), 1795-1806.

Ring, E. F. J., &Ammer, K. (2012). Infrared thermal

imaging in medicine. Physiological measurement,

33(3), R33.

PhyCS 2016 - 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems

150

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., & Kagan, J. (1996). The

psychological significance of changes in skin

temperature. Motivation and Emotion, 20(1), 63-78.

Spalding, S. J., Kwoh, C. K., Boudreau, R., Enama, J.,

Lunich, J., Huber, D., .& Hirsch, R. (2008). Three-

dimensional and thermal surface imaging produces

reliable measures of joint shape and temperature: a

potential tool for quantifying arthritis. Arthritis

Research and Therapy, 10(1), R10.

Titman, D. J. (2001), Applications of thermography in non-

destructive testing of structures, NDT & E International,

34(2), 149-154.

Vos, Pieter, De Cock, Paul, Munde, Vera, Petry, Katja,

Noortgate, Wim Van Den , Bea, &Maes B. (2012) The

tell-tale: what do heart rate; skin temperature and skin

conductance reveal about emotions of people with

severe and profound intellectual disabilities? Res Dev

Disabil. 2012 Jul-Aug; 33(4): 1117-27.

Wilson, P R, Low, P A, Bedder, M D, Covigton, W E C,

and Rauck, R. (1996) Diagnostic algorithm for complex

regional pain syndromes Reflex Sympathetic

Dystrophy ed A Re-appraisal, W Jänig and M Stanton-

Hicks (Seattle: IASP Press) pp 93-105.

Detecting Thermal Emotional Profile

151