The STAPS Method

Process-taylored Introduction of Knowledge Management Solutions

Christoph Sigmanek and Birger Lantow

University of Rostock, Albert-Einstein-Str.22, 18051 Rostock, Germany

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Business Process Oriented Knowledge Management, Knowledge Management

System, Best Practices, Method.

Abstract: Nowadays, knowledge is recognized as an important enterprise resource. Thus, knowledge management is

perceived as a necessary management task. Process oriented knowledge management is an approach that

aligns knowledge management with the requirements of knowledge intensive processes. However, existing

approaches to the implementation of process oriented knowledge management either operate on a very high

abstraction level, incorporating much effort for operationalization in practice or on a very detailed level

concentrating on process modelling. This paper introduces the STAPS method for the process oriented

analysis and implementation of knowledge management solutions. It allows the assessment of already existing

knowledge management solutions, the adoption of new solutions based on best practises, and a tailoring to

organizational needs. In a case study, the applicability of STAPS is proved.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, knowledge is recognized as an important

enterprise resource. Thus, knowledge management is

perceived as a necessary management task. Here,

business process oriented knowledge management

aims at the ways of dealing with knowledge as well

as requirements for knowledge and knowledge

activities (use, production, and transfer of

knowledge) in business processes. Remus puts

knowledge-intensive business processes in the focus

of a process-oriented knowledge management

(Remus 2002, p.108). Here lies the biggest success

potential for knowledge management.

Knowledge intensive business processes are

commonly found in knowledge-intensive domains

and are characterized by a high degree of complexity.

Control flow varies widely, so that a high

coordination and communication effort is required.

Knowledge-intensive processes are often poorly

structured, show a high number of participants

(experts), and are difficult to plan. Due to their nature,

it is difficult to reassign tasks to different individuals

(Remus 2002, pp. 104-117). Heisig sees as the most

relevant criterion of knowledge-intensive processes

that required knowledge can be planned ahead only

in a limited manner (Heisig 2002).

Therefore, planning and organizing knowledge

management with regard to these processes should

rather consider modelling the context of knowledge

intensive processes than modelling the processes

themselves in detail. For example, there are

approaches to knowledge intensive process

modelling that omit control flows or remain at a very

abstract level (Sigmanek and Lantow 2015).

Most organizations have already some knowledge

sharing solutions. In the most primitive way this is a

shared file storage and of course a regular meeting.

Additionally, not all processes within an organization

are knowledge intensive and not all knowledge

intensive processes need special support or can be

improved compared to existing solutions. Thus, a

method for the introduction of a knowledge

management solution should start with an assessment

of the organization’s processes, existing knowledge

management solutions and the context of knowledge

intensive processes. Looking into existing approaches

for the introduction of knowledge management

solutions, they mostly fail in one aspect (Sigmanek

and Lantow 2015): KMDL (Gronau 2004)

concentrates on a very detailed process model. KPR

(Allweyer 1998, pp. 163 - 168) remains on a strategic

level and does not consider existing solutions.

PROMOTE (Hinkelmann et al. 2002, pp. 65 - 68)

mainly focuses on IT support for knowledge

Sigmanek, C. and Lantow, B.

The STAPS Method - Process-taylored Introduction of Knowledge Management Solutions.

DOI: 10.5220/0006049901810189

In Proceedings of the 8th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2016) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 181-189

ISBN: 978-989-758-203-5

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

181

managements but does not consider process context.

KIPN (França et al., 2013) just provides a notation for

process modelling and analysis. GPO-WM (Heisig

2002, pp. 47 – 59) looks into the context of processes

and suggests best practises for known knowledge

management related problems. However, GPO-WM

does not consider existing solutions, does not allow

much tailoring.

In contrast, STAPS (Scoping-Tayloring-

Analysis-Problem-Solving) starts with an analysis of

process context and existing knowledge management

solutions. Furthermore, it compares the

organization’s setup with best practise solutions for

knowledge management. There is still a need for a

methodology that helps small and medium sized

enterprises dealing with knowledge management

(Borchardt et al. 2014). Due to thigh adaptability of

STAPS, the method is also fit for these settings. A

major mechanism to ensure this is the tailoring as part

of the method.

In the following, this paper presents an overview

of relevant best practises in knowledge management

in section 2. Section 3 then describes the STAPS

method. A case study that shows the applicability of

STAPS is sketched in section 4. Finally, section 5

draws conclusions und makes suggestions for further

steps regarding research and implementation of

STAPS.

2 BEST PRACTISES IN

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

There are two aspects regarding best practises in

knowledge management. First, knowledge

management must contribute to organisational

success. Thus, appropriate knowledge management

functions and IT as well as organizational solutions

that implement these functions need to be identified.

Second, knowledge management will only be

successful in the right organizational context (Lehner

et al. 2007). Hence, success factors for knowledge

management regarding management and culture in

organisations have to be considered.

2.1 Knowledge Management Solutions

A lot of business processes contain unproductive

efforts. These efforts result from search times, errors,

double work, and loss of knowledge. Knowledge

management can contribute to the organizational

success by reducing or avoiding them. Another

benefit of knowledge management is an increased

product quality by revealing process knowledge and

making processes controllable. (Bergrath et al. 2004,

pp. 115-116)

Aiming at these benefits, a set of questions that

need to be answered for the implementation of

knowledge management can be derived:

How can …

search times be reduced?

knowledge be found?

double work be avoided?

explicit knowledge be stored?

knowledge loss be avoided?

knowledge be transferred?

And additionally:

What IT-support exists for knowledge

management?

In the following, each of these questions is addressed.

How can search times be reduced? Here, the

reasons for search times are important. Search for

knowledge is necessary when a worker does not carry

the knowledge that is required for performing his or

her task. Thus, the required knowledge needs to be

identified, found and transferred to the worker. Best

practise solutions provide functionality that supports

the search for knowledge carriers. This leads to the

next question.

How can knowledge be found? It is essential to

have a systematic way to structure the knowledge.

Thus, documents containing knowledge and

knowledge carriers must be connected consistently to

this knowledge structure. This structure can be

created using taxonomies, folksonomies, or

ontologies. Furthermore, this structure needs to be

maintained, knowledge must be accessible and

processible in order to foster the use of respective

knowledge management solutions. (Probst et al.

2012, pp. 197-221)

A best practise solution in this area are yellow

pages, making domain experts identifiable (Probst et

al. 2012, pp. 65-91; Stocker and Tochtermann 2010,

p. 117). Another solution is a central helpdesk that

automatically classifies requests using text analysis

methods. Having such a system as a single point of

entry, user specific views can be generated which also

contribute to a reduction of search times by pushing

relevant knowledge to the right workers (Heck 2002,

p. 171-183). Other solutions that help finding

knowledge are: project data bases, search engines,

data base management systems, content management

systems, and forums (Bredehorst et al. 2013, p.6).

How can double work be avoided? Double work

happens for example when content is maintained

separately at several locations. Party, this redundancy

is intended. However, in a lot of cases it is unwanted.

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

182

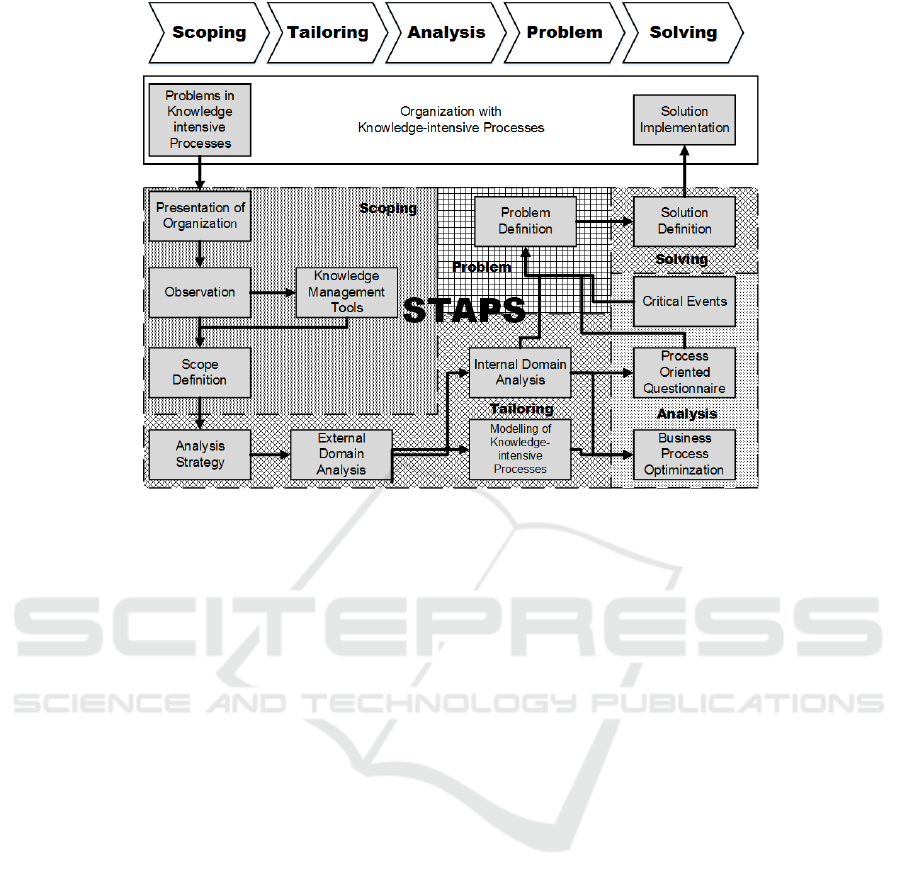

Figure 1: The STAPS method components.

A first step in avoiding double work is supporting the

search for knowledge as described for the previous

question. In addition, groupware systems and job

rotation are solution in order to avoid double work

(Bredehorst et al. 2013, p.6).

How can explicit knowledge be stored? Here, the

focus lies on quality of the stored knowledge. One

important aspect is the representation of knowledge.

There is no best way. A video for example can capture

movements while a full text search in a video is nearly

impossible. Thus, the appropriate representation

depends on the domain. However, techniques for

automated and semi-automated analysis and tagging

of streaming formats exist. Another aspect of

knowledge quality is the aging of knowledge.

Outdated knowledge must be removed from the

knowledge base. And at last, noise is a factor to pay

attention to. When capturing knowledge, the fraction

of irrelevant parts in the data set should be low in

order to support the use of knowledge (Bergrath et al.

2004, pp. 124-125). This includes audio and video

streams as well as e-mail communication containing

emails that are “off-topic”,

How can knowledge loss be avoided? Besides

appropriate storing of knowledge, knowledge

monopolies should be avoided. Hence, overlapping

personal knowledge bases of employees reduce the

knowledge loss if an employee becomes unavailable.

Furthermore, the knowledge structure should be

analysed for monopolies (Pogorzelska 2009, pp. 56-

60, 78-79).

If several individuals incorporate the same

organizational role a knowledge exchange between

all of them is important. Knowledge transfer is always

connected with a loss of knowledge. This is true

especially for a knowledge transfer via third and

fourth persons. Therefore, flat hierarchies are

suggested (Pogorzelska 2009, pp. 59-68). Further-

more, business processes should be structured in a

way that an employee carries the complete knowledge

that is needed to perform the process activities that

are assigned to him or her. Otherwise, knowledge

transfers would be necessary and a loss of knowledge

within the process execution is likely. However, in

many cases such a structure is not possible for

knowledge intensive processes. Thus, forming teams

that name responsibles for knowledge topics within

the teams is suggested (Bergrath et al. 2004, pp. 130).

How can knowledge be transferred? Transferring

complex knowledge, a collective memory performs

better than an individual one. Therefore, complex

knowledge should be transferred from one group to

another (Probst et al. 2012, pp. 197-221).

Other tasks of knowledge transfer are the

exchange of expert knowledge and of implicit

knowledge. If expert knowledge should be

transferred, techniques like knowledge relay (Stocker

and Tochtermann 2010, p. 117) and expert debriefing

are suggested.

For the transfer of implicit knowledge, a triad talk

is suggested (Dick 2010, pp. 375-378). In a triad talk,

domain expert and knowledge receiver work together

The STAPS Method - Process-taylored Introduction of Knowledge Management Solutions

183

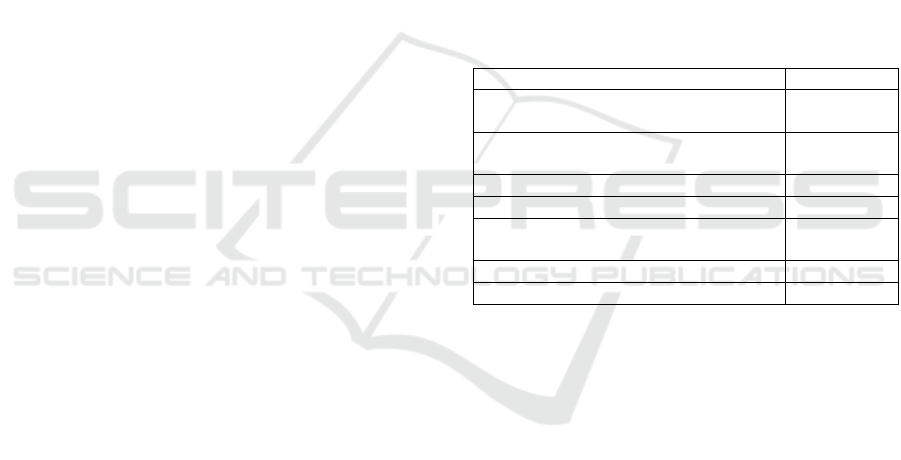

Table 1: STAPS guiding questions.

Knowledge Management Solution

Knowledge Resource or Carrier

Communication Channel

Is this solution known and

available?

Is this resource/carrier known and

available?

What is the fraction of relevant

information/knowledge?

Is the way access known?

How are the response times?

What is the probability of overseeing

information/knowledge?

Has the solution been used?

Is this resource/carrier frequently

used?

What information/knowledge is lost?

Was the solution helpful

How is the provided knowledge

quality?

Is the knowledge consistent at sender

and receiver side?

How was the solution applied?

What is done to improve knowledge

quality?

with a moderator. If the transfer process is planned to

last for a longer period of time, an additional expert

(mentor) may be assigned (Maier 2007, p.169).

What IT-support exists for knowledge

management? Maier (2007, pp. 548-563) identifies 7

functional areas: (1) Search, (2) Presentation, (3)

Publication, (4) Acquisition, (5) Communication, (6)

Cooperation, and (7) E-Learning. There are several

application systems that provide the respective

functionalities. Each of them has specific strengths

and weaknesses. Generally, knowledge management

systems combine several if not all of these

functionalities.

2.2 Management and Culture

As already stated, the success of knowledge

management implementations depends on the

organizational context. For example, the knowledge

management assessment tool which was developed

by the American Productivity & Quality Center

(APQC) can be used to check these factors (North

2011, p. 200).

Lehner et al. (2007) analysed success factors of

knowledge management in a multi case study (64

cases). They defined measurable indicators for

success in the areas ‘management’ and ‘culture’.

Management subsumes the engagement of

management representatives for knowledge

management while Culture addresses the behaviour

and attitude of employees towards knowledge

management as well as their involvement in

knowledge management processes. Example

indicators are (Lehner et al., 2007, pp. 27-34):

Management:

1. Knowledge Management is actively lived

2. Knowledge Management is financially

supported.

Culture:

1. Meetings are conducted face-to-face

2. Culture of knowledge sharing

A complete list can be found in the named source.

3 THE STAPS METHOD

In the following, the STAPS method is presented. It

has been developed in order to have a method for the

introduction of knowledge management solutions

that can be tailored to the needs of an organization.

Thus, there is no organization wide major step to an

integrated knowledge management system required

as suggested by Allweyer (1998), nor is STAPS just

providing a notation for knowledge intensive

processes. Existing knowledge management

solutions can be improved and the scope of analysis

can be set to single processes and organizational units

based on STAPS. Thus, STAPS is also a valuable tool

for small and medium sized companies. Furthermore,

STAPS uses the best practices for knowledge

management as described in section 2 in order to

provide means for analysis and for the creation of an

action plan in order to solve found problems.

STAPS consists of the following phases: (1)

Scoping (2) Tailoring (3) Analysis (4) Problem and

(5) Solving (see figure 1). Each of them is described

in a separate subsection.

3.1 Scoping

The Goal of the Scoping Phase is to determine

processes, tools, and possibilities for the further

analysis of knowledge management solutions. This

phase is divided into four method components: (1)

Initial Workshop; (2) Observation; (3) Assessment of

Knowledge Management Tools and (4) Scope

Definition.

Initial Workshop. The initial workshop is used to

provide an overview of the domain und the business

activities of the analysed organization. Additionally,

first problems perceived by the management are

collected. A second function of the workshop is

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

184

getting to know each other and to form a base for

cooperation throughout the analysis project.

Observation. Since the initial workshop is held

with participants on management level, it is likely that

the subjective view of a few representatives prevails.

Furthermore, not all information to determine the

scope of a detailed analysis can be gathered. Thus,

business process execution is observed and compared

to the results of the initial workshop. The observation

is used to determine roles, their responsibilities and

their usage of information systems, especially those

that implement knowledge management

functionality. The observation can be undertaken

either in-place or in form of a workshop where typical

work activities are demonstrated and explained.

Knowledge management tools. In this step the

currently used knowledge management tools are

assessed. They are categorized regarding

functionality (see section 2.1, What IT-support exists

for knowledge management?) and their usage in

business processes. The resulting map of knowledge

management tools helps to identify areas that need

deeper analysis and to transform general STAPS-

questionnaires to organization specific instances. For

example, “How do [workflow management systems]

support your daily work?“ turns into „How does JIRA

support your daily work?”. Thus, interviewees do not

need to know workflow management systems in

general but only the concrete systems they use.

Scope Definition. Here, process parts are

identified, that should be part of further analysis. This

assessment considers two dimensions. First,

relevance of knowledge within in the processes or

process parts needs to be considered. The basic

question is whether knowledge management

solutions are the right tool to improve process

performance. Knowledge intensity within the

processes is determined using a questionnaire based

on the work of Remus (2002). Second, the

organizational priorities have to be taken into

account. Thus, identified knowledge intensive

processes are prioritized.

The Scoping results in a list of processes or

process parts that will be subject of further analysis.

3.2 Tailoring

The Tailoring is the second phase of STAPS. It

consists of the method components (1) Analysis

Strategy; (2) External Domain Analysis; (3) Internal

Domain Analysis and (4) Modelling of Knowledge

Processes.

Analysis Strategy. A further tailoring of the

STAPS process to the organization and its goals is

done. The analysis strategy determines time frame,

resources, and cooperation forms for the analysis

project. Additionally, the core goals of the analysis

need to be set. This comes together with expectations

for the outcome and management commitment to the

analysis project. Missing management commitment is

a common cause for failed knowledge management

related projects. The goal of the STAPS project

should be aligned with the organizational goals in this

step.

External Domain Analysis. Sector specific

processes and knowledge management solutions are

analysed and transferred to the organizational

context. Literature analysis is used in order to find

reference processes. The general goal of this method

component is the use of the advantages provided by

reference models (for example ITIL 2011). They

should contain best practice solutions and they can be

used for communication regarding sector specific

terms and their semantics. Thus, the internal analysis

is supported by the use of a common vocabulary. If

there are no reference models there is still the same

potential in collecting sector specific knowledge

regarding processes and terms.

Internal Domain Analysis. Here, the organization

itself and cross-process aspects are analysed.

Regarding organizational structure and culture, there

is a focus on reasons for employee fluctuation and on

inhibitors/catalysts of knowledge sharing.

Furthermore, important terms and concepts are

collected and mapped to existing reference models

and to business processes.

Modelling Knowledge Intensive Processes.

Knowledge intensive processes and their variants are

modelled with a role perspective. The interviews for

gathering the required information are tailored based

on the results of the scoping phase (map of knowledge

management tools) and the domain analyses

(reference processes, reference terms, and

organizational structure). Knowledge carriers are

identified. Activities that produce or require

knowledge collected as well as the typical ways of

knowledge transfer connected to these activities.

STAPS intentionally does not use an instance

based model of knowledge intensive processes as

suggested for KMDL. This is because, the

transferability of the analysis results would be

compromised if just the situation of a single subject

would be modelled. Furthermore, no special notation

for process modelling is required. As shown by

França et al. (2012), existing modelling notations for

business processes cover a majority of modelling

requirements for knowledge intensive processes (e.g.

EPC, BPMN). Missing elements can be added.

The STAPS Method - Process-taylored Introduction of Knowledge Management Solutions

185

Another argument for not using special notations lies

in the better understandability and utility of the

models for the organisation’s representatives if a

common modelling notation is used.

The result of modelling knowledge intensive

processes is an as-is-model that can be further

analysed. The model contains the processes and their

context for further analysis.

3.3 Analysis

In analogy to GPO-WM WM (Heisig 2002), STAPS

uses guiding questions for the identification of

problems. Due to the restrictions regarding

modelling, formal reports as suggested for KMDL are

not considered. Instead, the method of critical events

is used (Trier and Müller 2014). It also provides a

more objective view on the processes. Not all

problems related to knowledge intensive business

processes are addressable by knowledge management

solutions. Some problems may be solved by classical

business process optimization techniques (see below)

which is also part of STAPS. In consequence, the

analysis phase has the method components (1)

process Oriented Survey; (2) Business Process

Optimization and (3) Critical Events.

Process Oriented Survey. For the interviews, the

method for the assessment of knowledge intensive

processes by Trier and Müller (2004) has been

adopted and significantly extended. Additionally, a

focus on the quality of knowledge transfer has been

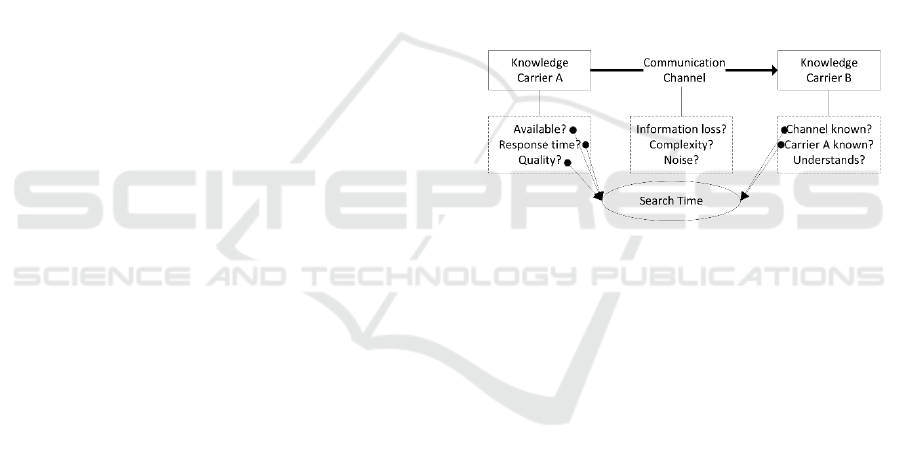

set. Figure 2 shows the conceptual model of

knowledge transfer quality. It shows, that search

times increase due to insufficient transparency and

knowledge quality. Loss of knowledge occurs in the

communication channels. Thus, these aspects became

part of the questionnaire. The questionnaire is

considered to be process oriented because it starts

with the understanding of the process before

addressing knowledge management issues based on

it. This part of the questionnaire is shown in table 1.

The questions consider knowledge solutions,

carriers/resources and communication channels with

a specific sub-set of questions. The questions are

going to be applied to all relevant entities that have

been identified in the tailoring phase. However, the

focus is not only on Problems but considers all

aspects of a SWOT analysis. A complete picture of

the processes should be created this way. In the next

phases (Problem /Solving), the responsible actors

should be aware of strengths that might get lost and

risks caused by organizational changes.

Critical Events. The observation of critical events

is a second input for the identification of problems.

Trained observers watch for deviations in the regular

process flow. They capture how the employees react

on these deviations. Additionally, bottlenecks and

communication problems are documented. Thus,

observing critical events provides valuable input for

the analysis.

Business Process Optimization. Methods of

classical process optimization are applied (see Arndt

2015, pp. 35-42; Koch 2011, pp. 115-183; Wolf et al.

2013, pp. 203-221). A prerequisite for this step is that

the processes have been modelled in a process

modelling notation. It is analysed whether activities

can be parallelized or omitted. Also bottlenecks and

redundant activities can be identified. These problems

of classical process optimization are not further

considered here because the focus is on knowledge

management solutions. However, in a real world

environment re-organization projects should be

initiated if the potential benefit of process

optimization is high enough.

Figure 2: Quality of a knowledge transfer.

3.4 Problem

In order to derive a concrete action plan from the

analysis results, these have to be assessed.

Weaknesses and risks are rated regarding the need for

action and the effort for solving them. This includes a

comparison of the as-is-model with best practises in

knowledge management (see section 2), including

organisational structure and culture. Also

interdependencies between problems are taken into

account. The following questions are in focus:

What is the problem?

Is it a current problem or has it been solved?

How often does the problem occur?

Is the problem found to be threatening business?

Are there workarounds?

What consequences does the problem have?

Are there dependencies with other problems?

After categorization of the identified problems, an

ordered list of problems that actually need action is

provided.

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

186

3.5 Solving

In the Solving Phase, concrete measures to address

found problems regarding knowledge management

are selected. This starts from problems that can be

matched to the questions defined in section 2.1. If

there is a match, knowledge management solutions

that are assigned as best practises to the respective

questions are appropriate solution candidates.

Furthermore, problems that arise from deviations

between actual process execution and the reference

processes found in external domain analysis can be

solved by reorganisation. Deviations from best

practises (see section 2.2) regarding organizational

culture and structure will need further investigation.

There is no off-the-shelf solution. However, a list of

problems and solution candidates is created in the

solving phase. Before a decision is made about

actions to solve the found problems, the effort of each

of the solution candidates needs to be estimated and

possible side effects have to be collected. In the last

step the representatives of the organization decide

about the action plan based on the prioritized

problems together with the respective solution

candidates. Due to the involvement of organizational

representatives, a better commitment to the

implementation of planned actions is expected.

4 CASE STUDY

The STAPS method has been applied in a small

company (24 employees) that provides software

maintenance services. The Scope-Phase has been

used to assess all IT-systems that provide knowledge

management related functionality and to identify

processes that were subject to the STAPS-based

analysis. Using the questionnaire in accordance to

Remus (2002), the following knowledge intensive

processes have been identified and selected: (1)

Change Request (2) Bug-fixing (3) Setup project

organization (4) Integration of new team members.

The domain analysis that has been performed as

part of the Tailoring-Phase identified ITIL as source

for reference processes in the external analysis. For

the internal domain, the organizational structure and

general aspects of organizational culture and

management regarding knowledge management have

been assessed (see best practises in section 2.2). The

following shortcomings have been found already in

this phase: (a) Knowledge management is supported

but not used at higher level management (b) Access

to knowledge management systems is complex (c)

knowledge management activities are additional

effort to customer projects which is not billed (d)

Knowledge management activities are not integrated

into the business processes.

Based on the results of the Tailoring-Phase, the

process oriented questionnaires for the Analysis-

Phase have been created. Taking the process (3)

Setup project organization as an example, the

following knowledge sources/carriers have been

assessed: (1) Employee data base (2) HelpDesk (3)

Higher management (4) Customer (5) File Server (6)

Software Maintenance Guidebook. It revealed, that

information in the employee database was outdated in

some cases and this database was seldom used.

Furthermore, feedback and improvements regarding

the helpdesk and the software maintenance

guidebook were only provided by half of the staff.

Table 2 shows the problems regarding knowledge

management and their ratings as a result of the

Problem-phase.

Table 2: Problems identified based on STAPS.

Problem

Importance

No single point of entry for knowledge

management systems

Low

Different usage level of knowledge

management tools

Medium

Documentation is not persistent

High

Inconsistent terminology

Low

Problems in workshop/meeting

organisation

High

High number of contacts on customer side

High

Management is overstrained

Medium

Additionally, management problems (see section 2.2)

and structural problems have been identified and

assessed.

Based on the lists of problems an action plan has

been developed in the Solving-phase. It includes for

example new rules for workshop/meeting

organization, a standard terminology for project

documentation and the introduction of a mentoring-

program for new team members.

Overall, the case study showed the applicability

of STAPS. The company’s representatives

considered the outcome of the STAPS implemen-

tation as useful.

5 CONCLUSION

STAPS shows the following characteristics by

design:

Flexible tailoring even to small knowledge

management projects

The STAPS Method - Process-taylored Introduction of Knowledge Management Solutions

187

Inclusion of process context

Inclusion of existing knowledge management

solutions

Assessment of knowledge sources/carriers

Best practise solutions

Involvement of stakeholders

Stakeholder specific adaptation of method

components

Inclusion of classical process improvement

approaches

The performed case study showed that these

characteristics also hold for an application of STAPS

in practise. More cases should be collected in order to

improve the method and its components. A major

issue is the question of scalability. Some of the

suggested method components may not be applicable

at large scale. For example, the observation of critical

events is time consuming and will increase effort

highly in large settings.

An aspect for further improvement of the method

is tool support. Text analysis techniques and mobile

data collection solutions may reduce effort and allow

automated identification of problems.

REFERENCES

Allweyer, T.: Wissensmanagement mit ARIS-Modellen.

In: Scheer, A.-W.: ARIS - vom Geschäftsprozeß zum

Anwendungssystem, 3. Auflage, Springer Verlag,

Berlin 1998, pp. 162-168.

Arndt, H.: Logistikmanagement, Springer Fachmedien,

Wiesbaden 2015.

Bergrath, A. et al.: Wissensnutzung in Klein- und

Mittelbetrieben: Gestaltung, Optimierung und

technische Unterstützung wissensbasierter

Geschäftsprozesse, Wirtschaftsverlag Bachem, Köln

2004.

Borchardt, Ulrike; Kwast, Thomas; Weigel, Tino

Integrating the IS Success Model for Value-Oriented

KMS Decision Support Business Information Systems

Workshops - BIS 2014 International Workshops,

Larnaca, Cyprus, May 22-23, 2014, Revised Papers ,

pp. 168--178.2014.

Bredehorst, B. et al.: Wissensmanagement-Trends 2014-

2023: Was Anwender nutzen und Visionäre erwarten,

Pumacy Technologies, 2013.

Dick, M. et al.: Wissenstransfer per Triadengespräch: Eine

Methode für Praktiker. In: ZFO – Zeitschrift Führung

und Organisation, Schäffer-Poeschel Verlag, Stuttgart

06/2010, pp. 375-383.

França, J.B.S., Baião, F.A., Santoro, F.M.: A Notation for

Knowledge-Intensive Processes. In: Proceedings of the

2013 IEEE 17th International Conference on Computer

Supported Cooperative Work in Design, 2013, p. 190-

195.

Gronau, N., Müller, C., Uslar, M.: The KMDL Knowledge

Management Approach: Integrating Knowledge

Conversions and Business Process Modelling. In:

Karagiannis, D., Reimer, U.: Practical Aspects of

Knowledge Management. 5th International

Conference, PAKM 2004, Vienna December 2004.

Heck, A.: Die Praxis des Knowledge Managements:

Grundlagen, Vorgehen, Tools, Vieweg Verlag,

Braunschweig 2002.

Heisig, P.: GPO-WM: Methode und Werkzeuge zum

geschäftsprozessorientierten Wissensmanagement. In:

Abecker et al.: Geschäftsprozessorientiertes

Wissensmanagement, Springer Verlag, Berlin

Heidelberg 2002, pp. 47-64.

Hinkelmann, K., Karagiannis, D., Telesko, R.: PROMOTE:

Methodologie und Werkzeug für

geschäftsprozessorientiertes Wissensmanagement. In:

Abecker et al.: Geschäftsprozessorientiertes

Wissensmanagement, Springer Verlag, Berlin

Heidelberg 2002, pp. 65-90.

ITIL: Service Transition; ITIL v3 core publications / OGC,

Office of Government Commerce, 2

nd

edition, TSO The

Stationery Office, London 2011.

Koch, S.: Einführung in das Management von

Geschäftsprozessen. Springer Verlag, Berlin

Heidelberg 2011.

Lehner, F. et al.: Erfolgsbeurteilung des

Wissensmanagements: Diagnose und Bewertung der

Wissensmanagementaktivitäten auf Grundlage der

Erfolgsfaktorenanalyse. In: Schriftenreihe

Wirtschaftsinformatik, Diskussionsbeitrag W-24-07,3.

ed., Passau 2007.

Maier, R.: Knowledge Management Systems: Information

and Communication Technologies for Knowledge

Management, 3. Auflage, Springer Verlag, Berlin

Heidelberg 2007.

North, K.: Wissensorientierte Unternehmensführung:

Wertschöpfung durch Wissen, 5th edition, Springer

Gabler Verlag, Wiesbaden 2011.

Pogorzelska, B.: Arbeitsbericht - KMDL® v2.2: Eine

semiformale Beschreibungssprache zur Modellierung

von Wissenskonversionen, 2009.

Remus, U.: Prozeßorientiertes Wissensmanagement:

Konzepte und Modellierung. Dissertation, Universität

Regensburg, 2002.

Probst, G., Raub, S., Romhardt, K.: Wissen managen: Wie

Unter- nehmen ihre wertvollste Ressource optimal

nutzen, 7th edition, Springer Gabler Verlag, Wiesbaden

2012.

Sigmanek, Christoph; Lantow, Birger: A Survey on

Modelling Knowledge-intensive Business Processes

from the Perspective of Knowledge Management. In:

KMIS 2015 - Proceedings of the International

Conference on Knowledge Management and

Information Sharing, part of the 7th International Joint

Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge

Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K

2015), Volume 3, Lisbon, Portugal, November 12-14,

2015 , pp. 325--332.2015.

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

188

Stocker, A., Tochtermann, K.: Wissenstransfer mit Wikis

und Webblogs: Fallstudien zum erfolgreichen Einsatz

von Web 2.0 in Unternehmen, Springer Gabler Verlag,

Wiesbaden 2010.

Trier, M., Müller, C.: Towards a Systematic Approach

Capturing Knowledge-Intensive Business Processes.

In: Practical Aspects of Knowledge Management: 5th

International Conference, PAKM 2004, Proceedings,

Vienna 2004.

Wolf, E., Appelhans, L., Klose, R.: Prozessmanagement für

Experten: Impulse für aktuelle und wiederkehrende

Themen, Springer Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg 2013.

The STAPS Method - Process-taylored Introduction of Knowledge Management Solutions

189