Abstract Information Model for Geriatric Patient Treatment

Actors and Relations in Daily Geriatric Care

Lars R

¨

olker-Denker and Andreas Hein

Department of Health Services Research, University of Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany

Keywords:

Information Model, Geriatric Care, Knowledge Processes, Organisational Learning.

Abstract:

The authors propose an abstract information for geriatric care, the geriatric information model (GIM). They

adopt an information model from cancer care and introduce characteristics for geriatric care (patient popula-

tion, multidisciplinary and multi-professional approach, cross-sectoral approach). Actors (patients, physicians,

therapists, organisations), information objects, and information relations are defined. The GIM is validated by

mapping four typical knowledge processes (multi-professional geriatric team session, interdisciplinary clini-

cal case conferences, tumor boards, transition management) onto the model. The GIM is stated as useful for

understanding information flows and relations in geriatric care. All processes for validation can be mapped

onto GIM. In future work the GIM should be tested with more knowledge process and could also be used for

identifying gaps in the IT support of geriatric care. A study on high and low information quality in geriatric

care is also proposed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Patient treatment is a heavily data, information and

knowledge driven process with inter- and multidisci-

plinary cooperation (Chamberlain-Salaun et al., 2013,

74ff.). The amount of available data, information and

knowledge is increasing due to ongoing technologi-

cal developments and medical research. Medical in-

formation gathered in the domestic and mobile envi-

ronment of the patient will tighten this process in the

future.

These challenges also apply for geriatric patient

treatment (Mangoni, 2014) (R

¨

olker-Denker and Hein,

2015). Geriatric treatment is characterized by a target

population with complex diseases and an increasing

amount of patients, a multidisciplinary and multi-

professional treatment approach and a cross-sectoral

treatment (see section 3. For better understanding,

managing and controlling of information flows under

these constrains an abstract information model is nee-

ded.

In this work we adopt the approach of Snyder et

al (Snyder et al., 2011) who introduce an information

model for cancer care (see section 2). Afterwards, the

principles of geriatric care in Germany are introdu-

ced (see section 3). The model is then modified to

the needs of geriatric care based on literature review

and results from observational studies and interviews

with practitioners 4. The work is then validated with

four typical knowledge processes being mapped to the

model 5. The work then closes with a conclusion and

outlook 6.

2 ABSTRACT INFORMATION

MODEL

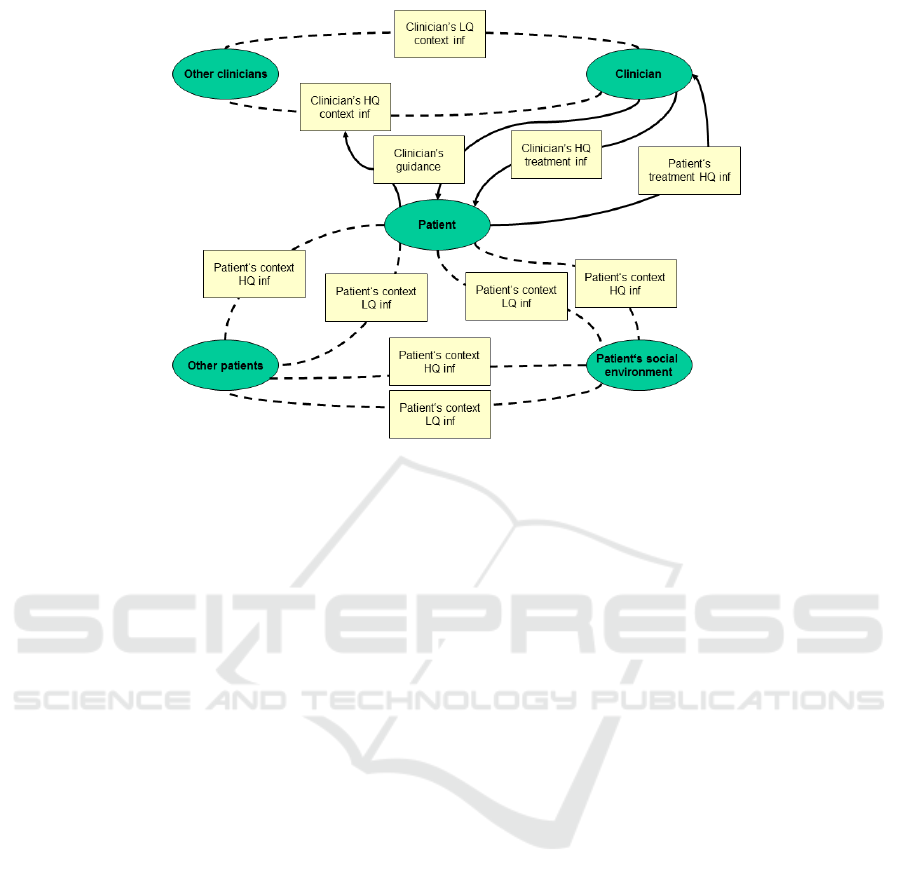

Snyder et al (Snyder et al., 2011) propose an abstract

information model for cancer care. Information in

cancer care is originated from clinician and patient

side (actors) and there are different communication

paths (relations). The actor-relations structure is de-

picted in figure 2.

2.1 Actors

Actors in the cancer care process resume have roles

and functions. In detail these are:

• Patient: treated by a clinician;

• Other patients: patients with same or similar dise-

ase and/or treated by the same clinicians or hospi-

talized in the same health organisation;

• Patient’s family and friends: people associated

with the treated patient;

222

RÃ˝ulker-Denker L. and Hein A.

Abstract Information Model for Geriatric Patient Treatment - Actors and Relations in Daily Geriatric Care.

DOI: 10.5220/0006106902220229

In Proceedings of the 10th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2017), pages 222-229

ISBN: 978-989-758-213-4

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Figure 1: Abstract Information Model based on (Snyder et al., 2011).

• Clinician: treating a specific patient;

• Other clinicians: other clinicians from the same

discipline (higher or lower rank), associated dis-

cipline or health organisation in contact with the

clinician in charge.

2.2 Relations

Patients and clinicians exist in a universe of informa-

tion. Snyder et al differentiate between high-quality

(HQ) information and low-quality (LQ) information,

with only a portion representing HQ information. HQ

information relations are:

• Clinician’s HQ treatment information: Combi-

nation of clinician’s medical knowledge (gained

from education and experience) and acquired me-

dical information (laboratory, medical imaging,

EEG, ECG) with the information gained from ex-

amining the patient (sensorial information);

• Patient’s HQ treatment information: Informa-

tion provided by the patient, e.g. drug intake,

health-relevant behaviours (nutrition, smoking) or

familial-genetic preload;

• Patient’s HQ HQ information: information shared

along the patient and its family and friends and

along the patient and other patients;

• Clinician’s HQ context information: Information

shared along the care team;

• Clinician’s guidance: Clinicians can direct their

patients to appropriate information resources.

At the same time, it must be noted that much of the

information available to both clinicians and patients

is biased, incorrect, or otherwise not useful. LQ in-

formation is shared frequently among patients.

• Patient’s LQ information: information shared al-

ong the patient and its family and friends, and al-

ong the patient and other patients;

• Clinician’s LQ context information: Low quality

information is shared even among clinicians.

3 CHARACTERISTICS FOR

GERIATRIC PATIENT

TREATMENT IN GERMANY

The following statements mainly focus on the speci-

fic situation in Germany which the specifics of the

German health care system being separated into dif-

ferent sectors. Nevertheless the used information in

geriatric care is comparable to other countries while

crossing the sectoral boarders is the main challenge

in Germany.

The information flows in geriatric treatment differ

from the information flows in cancer care. There are

four main reasons:

• Patient population;

• Multidisciplinary approach;

• Multi-professional approach;

• Cross-sectoral approach.

Abstract Information Model for Geriatric Patient Treatment - Actors and Relations in Daily Geriatric Care

223

3.1 Patient Population

Geriatric patients often suffer from chronic conditi-

ons, multimorbidity, polypharmacy and cognitive de-

ficits (Soriano et al., 2007, 15). They are often hos-

pitalized in nursing or retirement homes and, due to

cognitive impairments, not able to give proper infor-

mation about their health status. This results in a

strong demand on patients’ information from clinici-

ans’ view. In addition the amount of geriatric patients

is continuously rising with the demographic change in

most industrial societies (Kolb and Weißbach, 2015).

Therefor a structured information acquisition is es-

sential for the future success of geriatric treatment.

3.2 Multidisciplinary Approach

Due to multimorbidity and chronic conditions, geria-

tric treatment follows a holistic and systemic appro-

ach including several different kinds of medical disci-

plines. The most frequent disciplines involved are in-

ternal medicine, family medicine, psychiatry and neu-

rology followed by orthopaedics, surgery, trauma and

abdominal surgery (Nau et al., 2016, 603ff.).

3.3 Multi-professional Approach

Geriatric treatment and geriatric care is a highly

multi-professional process with several professions

included (Tanaka, 2003, 69ff.). In Germany, geria-

tric is organised in different ways. In case of sta-

tionary care selected patients can be treated under

supervision of the multi-professional geriatric team

(MGT) in the so-called complex geriatric treatment

(German: geriatrische fr

¨

uhrehabilitative Komplexbe-

handlung) (Kolb et al., 2014) (R

¨

olker-Denker and

Hein, 2015, 314f.). The MGT consists of physicians,

nurses, therapists (logopedics, physiotherapists, occu-

pational therapists, psychologists) and social workers.

3.4 Cross-sectoral Approach

Geriatric patient are often treated over sectors bor-

ders and in other health care organisations (HCOs). In

Germany, medical treatment is mainly separated into

ambulatory care/out-patient care (general physicians,

consulting/specialist physicians, ambulatory medical

services provide by hospitals) and hospital care/in-

patient care. Rehabilitation care, stationary care (nur-

sing homes, retirement homes) and home care are ot-

her relevant sectors for patient treatment.

4 GERIATRIC INFORMATION

MODEL

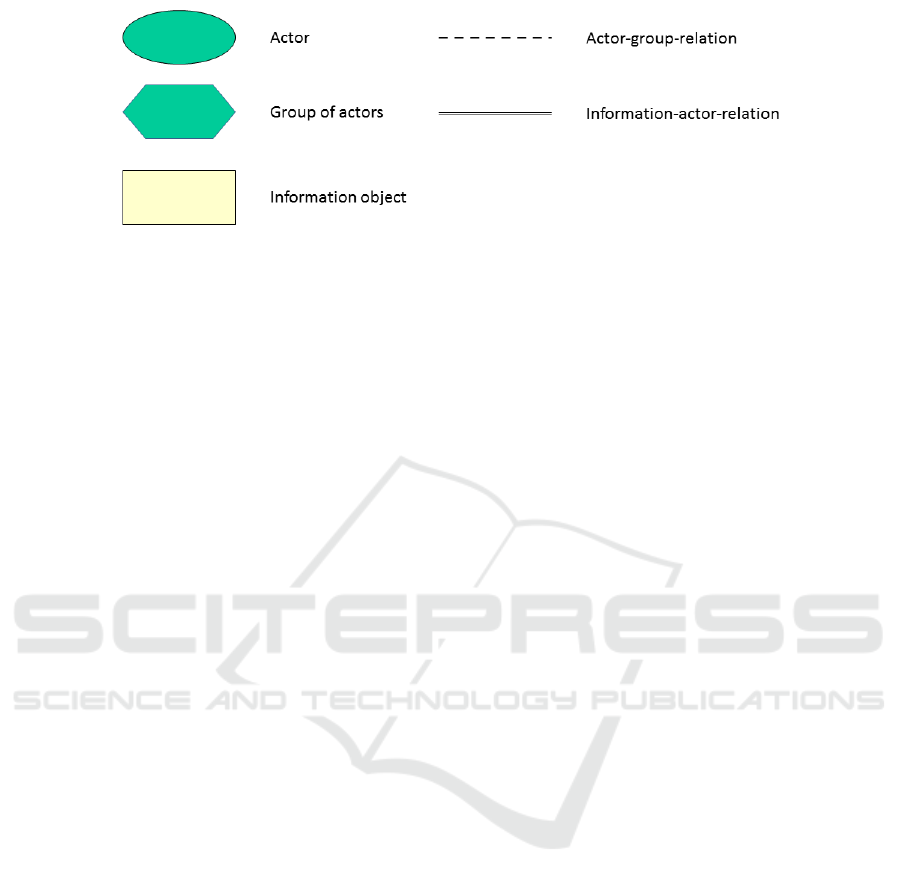

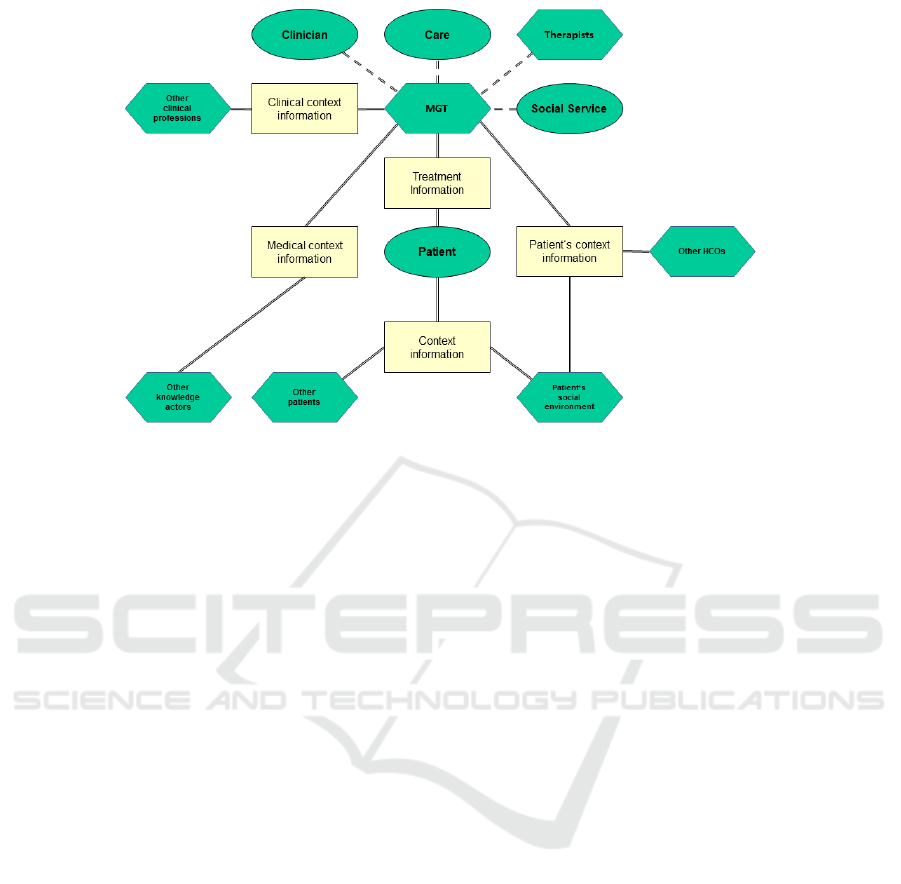

The key to the Geriatric Information Model (GIM)

is depicted in figure 4, the GIM itself with actor-

information relations in figure 4.2.

4.1 Actors

Within the GIM actors can be a single actor or a

group, consisting of several single actors or other

groups. Single actors describe a specific class of per-

sons with similarities (e.g. patients, carers, clinicians)

whereas a group subsume different actors. E.g. carers

are one actor (because having the same characteris-

tics) whereas therapists are group consisting of diffe-

rent kind of therapists.

• Patient (actor): geriatric patient treated by a clini-

cian;

• Other patients (group): patients with same or si-

milar disease and/or treated by the same clinicians

or hospitalized in the same health organisation;

• Patient‘s Social Environment (group): people as-

sociated with the treated patient;

• MGT (group):The team consists of clinicians,

nurses, therapists, and medical social workers;

• Clinician (actor): treating a specific patient and

part of the MGT with specific geriatric education

and training;

• Care (actor): nurses in charge for the patient, of-

ten with specific geriatric education and training;

• Therapists (group): logopedics, physiotherapists,

occupational therapists, psychologists and also ot-

her therapists if needed. They perform their spe-

cialised assessments to monitor the treatment out-

come;

• Social service (actor): medical social service wor-

kers are responsible for the social assessment,

communication with other HCOs, with courts (in

case of guardianship). They organise transition

management to other HCOs (care home, ambula-

tory care);

• Other HCOs (group): these are other HCOs also

responsible for the patient in the past and/or in the

future, often with HQ information being impor-

tant for the treatment. These HCOs can be from

ambulatory care/out-patient care (general physici-

ans, consulting/specialist physicians, ambulatory

medical services provide by hospitals), hospital

care/in-patient care (other hospitals), rehabilita-

tion care, stationary care (nursing homes, retire-

ment homes) and home care;

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

224

Figure 2: Key to Geriatric Information Model.

• Other clinical professions (group): these are all

other clinical profession not in direct contact with

the patient and not part of the MGT. This also in-

cludes other clinicians from the same discipline

(higher or lower rank), associated discipline or he-

alth organisation in contact with the clinician in

charge. They can be also from the geriatric disci-

pline and/or internal medicine and share their in-

formation and knowledge in regular clinical con-

ferences or they can be from other departments

and disciplines and are often involved by consul-

tation and/or patient transfer between the discipli-

nes;

• Other knowledge actors (group): all other relevant

knowledge actors outside the treating HCOs like

medical societies, quality circles, medical specia-

list publishers, libraries, other hospitals from the

same network (and not involved in the current tre-

atment of the specific patient) etc. This group of

actors could be also labelled as communities of

practice (CoPs) (Wenger, 2000, 229ff.) (Li et al.,

2009, 1ff.).

4.2 Information Objects

Information objects are shared between actors and

groups (see section 4.3 below).

• Treatment Information: about current treatment,

can contain diagnosis, treatment decisions, feed-

back from the patient about the progress, results

of shared-decision, etc.;

• Context information: disease and behaviour rela-

ted self-experiences (e.g. on procedures, medica-

tions), information about suitable contacts (speci-

alised hospitals, physicians, disease-related sup-

port groups etc.);

• Patient‘s context information: health behaviour in

the past, information on domestic and social envi-

ronment;

• Clinical context information: laboratory fin-

dings, electroencephalography (EEG), electrocar-

diography (ECG), medical imaging, other infor-

mation which is provided by specialised depart-

ments;

• Medical context information: medical back-

ground information, latest research results, clini-

cal guidelines.

4.3 Actor-information Relations

The possible information relations are listed and ex-

plained below:

• Patient - MGT - Treatment Information: this is

the main information relation in the geriatric treat-

ment process. All necessary treatment from invol-

ved professions (clinician, care, therapists, social

service) about the patient’s health status is resu-

med here;

• Patient - Other patients - Context information: this

information relation contains all disease-related

information, but also experience-related informa-

tion like information from other patients being tre-

ated by the same HCOs or even the same clinician;

• Patient - Patient‘s Social Environment - Context

information: this relation is comparable to the

previous relation because persons from the pa-

tient’s social environment could be also suffering

from a similar disease in the past or present;

• Other patients - Patient‘s Social Environment -

Context information: in this relation other patients

share their experience with the patient’s social en-

vironment. This could be information on how to

act in critical disease-related questions;

• MGT - Patient‘s Social Environment - Patient‘s

context information: through this relation infor-

mation about the patient’s situation at home is

shared. Treatment information could also be veri-

fied;

Abstract Information Model for Geriatric Patient Treatment - Actors and Relations in Daily Geriatric Care

225

Figure 3: Geriatric Information Model.

• MGT - Other HCOs - Patient‘s context informa-

tion: through this relation information about the

patient’s previous treatments (other hospitals, ge-

neral and specialist physicians), his domestic situ-

ation (in case of care or retirement home, or am-

bulatory care services) is shared;

• Patient‘s Social Environment - Other HCOs - Pa-

tient‘s context information: by this information

relation the patient’s social environments shares

patient’ context information with other HCOs like

information on health behaviour in other contexts

(previous disease, behaving in rehabilitation treat-

ments, etc.);

• MGT - Other clinical professions - Clinical con-

text information: this relation contains the in-

formation provided by consultations or morning,

lunch or radiological conferences with other spe-

cialist clinicians but also with other professions

like therapists not involved in the formal MGT;

• MGT - Other knowledge actors - Medical context

information: MGT members communicate with

other members of their COPs about their current

treatment, they investigate in (online) libraries or

journals.

5 VALIDATION OF GIM

To validate the GIM four typical knowledge processes

are mapped to the model. The mapped knowledge

processes are

• Multi-professional Geriatric Team Session

(R

¨

olker-Denker and Hein, 2015, 314f);

• Interdisciplinary Clinical Case Conferences

(R

¨

olker-Denker and Hein, 2015, 315);

• Tumor boards (R

¨

olker-Denker et al., 2015b, 54);

• Transition management (R

¨

olker-Denker et al.,

2015a, ).

5.1 Multi-professional Geriatric Team

Session

The MGT session is the regular meeting of the geria-

tric team 4.1. During this meeting all relevant infor-

mation is discussed:

• Treatment information: Feedback from the patient

on the health status is discussed as well as direct

impressions from all persons in contact with the

patient. Information passed towards the patient

is also discussed as well as the further treatment

process;

• Patient’s context information: this information is

of very high relevance for the MGT session. This

includes information about the domestic environ-

ment, e.g. how many stairs has the patient to

climb at home, are there any assisting services

or ambulatory care services, unhealthy behaviours

and supply with medication and assisting devices;

• Clinical context information: This includes from

other clinical professions like consultation results

from other disciplines, blood values and medical

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

226

imaging. During the session information which

will be forwarded to other clinical professions is

also discussed, e.g. information for treating sur-

geons;

• Medical context information: This includes in-

formation stored in clinical guidelines, e.g. the

guideline on urinary incontinence for geriatric

patients (AWMF (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wis-

senschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaf-

ten) (engl: Association of the Scientific Medical

Societies in Germany), 2016) but there also many

other guidelines for age-related health issues and

diseases (e.g. clinical nutrition, delirium, Parkin-

son disease, palliative care).

5.2 Interdisciplinary Clinical Case

Conferences

Interdisciplinary clinical case conferences consist of

members from different medical fields, the scope of

these conferences is to discuss complex patient cases

and to derive possible treatments (Feldman, 1999).

The conferences are organised on a regular basis

(R

¨

olker-Denker and Hein, 2015, 315) (R

¨

olker-Denker

et al., 2015b, 54). During these conferences the follo-

wing information is discussed:

• Treatment information: The MGT clinicians pre-

sent their treatment information about the patient;

• Clinical context information: The other members

of the clinical case conference provide their kno-

wledge about the specific case and discuss with

the inquiring clinicians possible treatment alter-

natives;

• Medical context information: other clinical pro-

fessions provide and explain clinical guidelines

the asking clinicians are not aware of.

5.3 Tumor Boards

Tumor boards are similar to clinical case conferences

but focus on oncological diseases and overcome sec-

toral boarders by connecting clinical physicians with

residential physicians and other oncological professi-

ons (R

¨

olker-Denker et al., 2015b, 54). Geriatric on-

cological treatment is also multi- and interprofessio-

nal, includes the patients’ social environment (Mag-

nuson et al., 2016) and even allows patient participa-

tion (Ansmann et al., 2014, 865ff.). Mainly the same

information is discussed as in the clinical case confe-

rence but in addition:

• Treatment information: in case of participation

the patient can give information about the health

status and also take part in the decision process on

further treatment;

• Patient’ context information: as residential physi-

cians are also part of the clinical case conference

(in terms of ”other HCOs”) they can provide more

context information about the patient as clinical

physicians could.

5.4 Transition Management

The goal of transition management is to ensure an op-

timal patient path through the different interfaces of

cross sectoral care (Huber et al., 2016). Transition

management does not only include communication

between hospitals and downstream health care organi-

sations (releasing a patient into rehabilitation or stati-

onary/ambulatory care), it also includes the communi-

cation between hospitals and upstream health care or-

ganisations (moving patient from stationary care into

hospitals) (Arve et al., 2009).

• Medical context information: up to now there is

no national guideline on transition management

by medical societies. But there are several local

networks that develop such guidelines and make

them publicly available;

• Patient’s context information: this information is

shared along all responsible HCOs and contains

information about further medication, previous

medication, recommendations on health-related

behaviour (nutrition, physical activities, etc.).

6 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

6.1 Conclusion

We developed an abstract geriatric information model

(GIM) for the purpose of better understanding the ty-

pical actors of geriatric treatment and the information

relations between them. The GIM was validated by

mapping typical care settings which occur during the

geriatric treatment. It was shown that all processes

could be mapped into the GIM and all defined actors

and information relations within the GIM are of re-

levance. Some knowledge processes are limited to a

subset of actors (e.g. clinical case conferences do not

imply the patient or the patient’s social environment)

whereas other knowledge processes include all actors

and information relations (e.g. the MGT session).

The GIM is not intended to be used for developing

sophisticated clinical information systems like other

approaches, e.g. the HL7 Clinical Information Mo-

deling Initiative (CIMI) (HL7 Clinical Information

Abstract Information Model for Geriatric Patient Treatment - Actors and Relations in Daily Geriatric Care

227

Modeling Initiative, 2016). The purpose of CIMI is to

develop interoperable healthcare systems on a techni-

cal basis. The focus is not on the communication bet-

ween persons involved in the geriatric treatment. Ne-

vertheless links to this work are mandatory in future

work because geriatric treatment is cross-sectoral 3.4

and includes data and information from different IT

systems.

6.2 Outlook

The GIM was only validated with four typical know-

ledge processes in geriatric treatment. Referring to

previous studies of the authors (R

¨

olker-Denker and

Hein, 2015) (R

¨

olker-Denker et al., 2015b) there are

more knowledge processes to be mapped towards the

GIM.

The approach of HQ and low quality information

was not included in the GIM so far. There have been

no dedicated studies on the information quality in

daily geriatric treatment so far and, for thus, there are

no validated results available. There are studies for

general information quality, e.g. analyse the impact

of internet health information (Laugesen et al., 2015)

but there are no dedicated studies in the geriatric con-

text.

The GIM can be also used for identifying gaps in

the IT landscape (Snyder et al., 2011). Healthcare

organisations can check all the actor-relation-couples

and see if there are gaps.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Metropolregion

Bremen-Oldenburg (reference number: 23-03-13) for

partly supporting this work.

REFERENCES

Ansmann, L., Kowalski, C., Pfaff, H., Wuerstlein, R., Wirtz,

M. A., and Ernstmann, N. (2014). Patient participa-

tion in multidisciplinary tumor conferences. Breast,

23(6):865–869.

Arve, S., Ovaskainen, P., Randelin, I., Alin, J., and Rautava,

P. (2009). The knowledge management on the elderly

care. International Journal of Integrated Care, 9.

AWMF (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Me-

dizinischen Fachgesellschaften) (engl: Association of

the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany) (2016).

Harninkontinenz bei geriatrischen patienten, diagnos-

tik und therapie.

Chamberlain-Salaun, J., Mills, J., and Usher, K. (2013).

Terminology used to describe health care teams: an

integrative review of the literature. Journal of Multi-

disciplinary Healthcare, pages 65–74.

Feldman, E. (1999). The interdisciplinary case conference.

Acad Med, 74:594.

HL7 Clinical Information Modeling Initiative (2016). Cli-

nical information modeling initiative [online].

Huber, T. P., Shortell, S. M., and Rodriguez, H. P. (2016).

Improving Care Transitions Management: Examining

the Role of Accountable Care Organization Participa-

tion and Expanded Electronic Health Record Functio-

nality. Health Serv Res.

Kolb, G., Breuninger, K., Gronemeyer, S., van den Heuvel,

D., L

¨

ubke, N., L

¨

uttje, D., Wittrich, A., and Wolff, J.

(2014). 10 jahre geriatrische fr

¨

uhrehabilitative kom-

plexbehandlung im drg-system [german]. Z Gerontol

Geriat, 47:6–12.

Kolb, G. F. and Weißbach, L. (2015). Demographic change

: Changes in society and medicine and developmental

trends in geriatrics. Der Urologe, 54(12):1701.

Laugesen, J., Hassanein, K., and Yuan, Y. (2015). The im-

pact of internet health information on patient compli-

ance: A research model and an empirical study. J Med

Internet Res, 17(6):e143.

Li, L. C., Grimshaw, J. M., Nielsen, C., Judd, M., Coyte,

P. C., and Graham, I. D. (2009). Use of communi-

ties of practice in business and health care sectors: a

systematic review. Implement Sci, 4:27.

Magnuson, A., Wallace, J., Canin, B., Chow, S., Dale, W.,

Mohile, S. G., and Hamel, L. M. (2016). Shared Goal

Setting in Team-Based Geriatric Oncology. J Oncol

Pract.

Mangoni, A. A. (2014). Geriatric medicine in an aging so-

ciety: Up for a challenge? Frontiers in Medicine,

1(10).

Nau, R., Djukic, M., and Wappler, M. (2016). Geria-

trics – an interdisciplinary challenge. Der Nervenarzt,

87(6):603–608.

R

¨

olker-Denker, L. and Hein, A. (2015). Knowledge process

models in health care organisations - ideal-typical ex-

amples from the field. In Proceedings of the Interna-

tional Conference on Health Informatics (BIOSTEC

2015), pages 312–317.

R

¨

olker-Denker, L., Seeger, I., and Hein, A. (2015a).

¨

Uberleitung aus sicht der krankenh

¨

auser - ergebnisse

aus semi-strukturierten leitfadeninterviews auf ebene

der gesch

¨

aftsf

¨

uhrung in der region metropolregion

bremen-oldenburg. In 14. Deutscher Kongress f

¨

ur

Versorgungsforschung. Deutsches Netzwerk Versor-

gungsforschung e. V. 7. - 9. Oktober 2015, Berlin.

R

¨

olker-Denker, L., Seeger, I., and Hein, A. (2015b). Kno-

wledge processes in german hospitals. first findings

from the network for health services research metro-

politan region bremen-oldenburg. In eKNOW 2015,

The Seventh International Conference on Information,

Process, and Knowledge Management, pages 53–57.

IARIA.

Snyder, C. F., Wu, A. W., Miller, R. S., Jensen, R. E., Ban-

tug, E. T., and Wolff, A. C. (2011). The role of infor-

matics in promoting patient-centered care. Cancer J,

17(4):211–218.

HEALTHINF 2017 - 10th International Conference on Health Informatics

228

Soriano, R. P., Fernandez, H. M., Cassel, C. K., and Leip-

zig, R. M. (2007). Fundamentals of Geriatric Medi-

cine : A Case-Based Approach. New York : Springer

Science+Business Media, LLC, New York.

Tanaka, M. (2003). Multidisciplinary team approach for

elderly patients. Geriatrics & Gerontology Internati-

onal, 2003, Vol.3(2), pp.69-72, 3(2):69.

Wenger, E. (2000). Communities of Practice and Social

Learning Systems. Organization, 7(2):225–246.

Abstract Information Model for Geriatric Patient Treatment - Actors and Relations in Daily Geriatric Care

229