Design a Study for Determining Labour Productivity Standard in

Canadian Armed Forces Food Services

Manchun Fang

Centre of Operational Research and Analysis, Defence Research Development Canada,

National Defence Canada, 101 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Canada

Keywords: CAF Food Services, Performance Measure, Labour Productivity, Study Design.

Abstract: Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) Food Services recently implemented a standardized menu at all static

service locations. Within this new regime, CAF Food Services requires a standard against which they can

measure labour performance and use to inform future rationalization of staffing. To start, a pilot study was

conducted in February and March 2015 to collect labour performance data. In this paper, we review the

results from the pilot study. Due to issues identified with the pilot study, this paper also proposes a revised

design and analytical approach for a follow-on study.

1 INTRODUCTION

Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) Food Services is a

decentralized function with an estimated value

exceeding $150 Million in cost per year for fresh

feeding. As functional authority for CAF Food

Services, Strategic Joint Staff (SJS) Directorate

Food Services recently implemented a three-week

National Standardized Cycle Menu (NSCM) on all

static feeding facilities, which has been rolled out

across all CAF static feeding facilities since the

beginning of November 2014. However, currently

CAF Food Services does not have a labour

performance standard that can be used to measure

and compare the labour performance in CAF Food

Services (Mat J4 2014).

Unlike most of other food industry, the CAF

Food Services is not profit driven and fulfilling the

operational needs is its first priority. Determining a

CAF specific labour performance standard for CAF

Food Services is significant. As a start, SJS

Directorate Food Services planned a pilot study and

collected labour performance data in February and

March 2015. Directorate Materiel Group

Operational Research (DMGOR) was later tasked to

provide analytical support. The objective of this

work is to review the results from the pilot study.

Furthermore, due to the issues identified with the

pilot study, the work is also used to provide SJS

Directorate Food Services a more rigorous study

design and analytical approach for a future follow-

on study.

2 RESULTS FROM THE PILOT

STUDY

2.1 Data Collection

It is noted here that Operational Research and

Analysis was not significantly consulted to set up of

the pilot study including the aspects, e.g., the target

determination, sample selection, and the sample size

determination. In addition, the grouping of facilities

and the order of visits were determined by financial

consideration, i.e., minimizing the travel cost, not by

statistical consideration. Furthermore, the choices of

the dates were not randomly selected and the

facilities were aware of the dates of visits prior to

the data collection.

An existing Excel-based Labour Performance

Data Collection Tool (Whiting 2015) was used in

the data collection process. Annex A Tables A1

provides a summary of data obtained from the pilot

study.

2.2 Data Exploration

This section will summarize the results from the

pilot study. Although the design of the pilot study is

Fang M.

Design a Study for Determining Labour Productivity Standard in Canadian Armed Forces Food Services.

DOI: 10.5220/0006110702190227

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems (ICORES 2017), pages 219-227

ISBN: 978-989-758-218-9

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

219

not ideal, it provides useful prior information needed

for designing a more rigorous future follow-on

study.

Volume of Activity

In CAF Food Services, Volume of Activity is used

to record the number of meals (including breakfast,

lunch and dinner) served in a facility during a fix

time period (e.g., daily, monthly or yearly). For the

pilot study, Volume of Activity records the total

number of meals served during the pilot study

period, i.e., a five day period. The Volume of

Activity for five days ranges from 2,161, 2,335,

3,037, 4,514, 10,613 and 17,883 for Halifax,

Esquimalt, Trenton, Wainwright, Gagetown and

Saint-Jean respectively.

Number of Meals per Labour Hour

The number of meals per labour hour is calculated

by dividing the total number of meals served by the

total number of labour hours spent including labour

hours spent by both military and civilian employees

see eqn. (1):

(1)

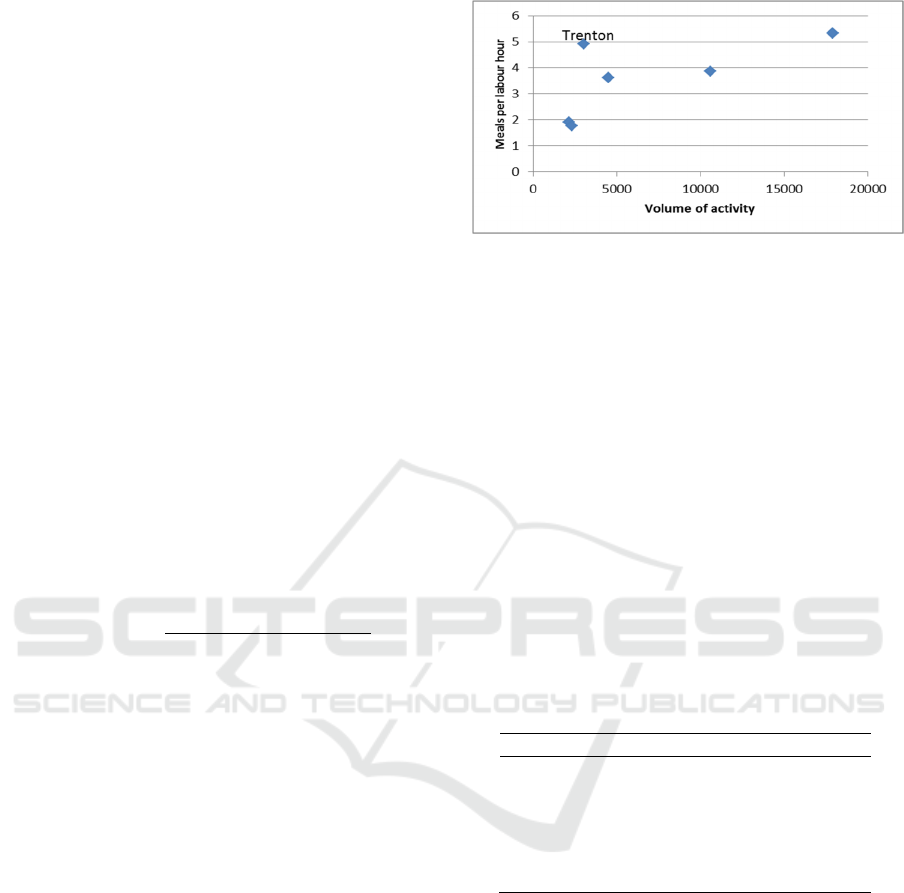

There is a large variation on the number of meals

per labour hour across facilities calculated, which

are 1.8, 1.9, 3.6, 3.9, 4.3 and 5.3 for Esquimalt,

Halifax, Wainwright, Gagetown, Trenton and Saint-

Jean respectively (data from Table A.1).

The Volume of Activity is reported as the most

important factor that has impact on the labour

productivity (Tremblay 2004). The data from the

pilot study also suggests that except for Trenton

(Different from the other facilities, Trenton also

provides flight feeding which requires less time on

serving the food than the in person serving.), there is

a relationship between the Volume of Activity and

the Number of Meals Per Labour Hour: i.e., the

greater the Volume of Activity, the greater the

Number of Meals Per Labour Hour (which is

consistent with the finding in Tremblay 2004) (See

Figure 1).

Figure 1: Volume of activity vs. number of meals per

labour hour.

Labour Cost per Meal

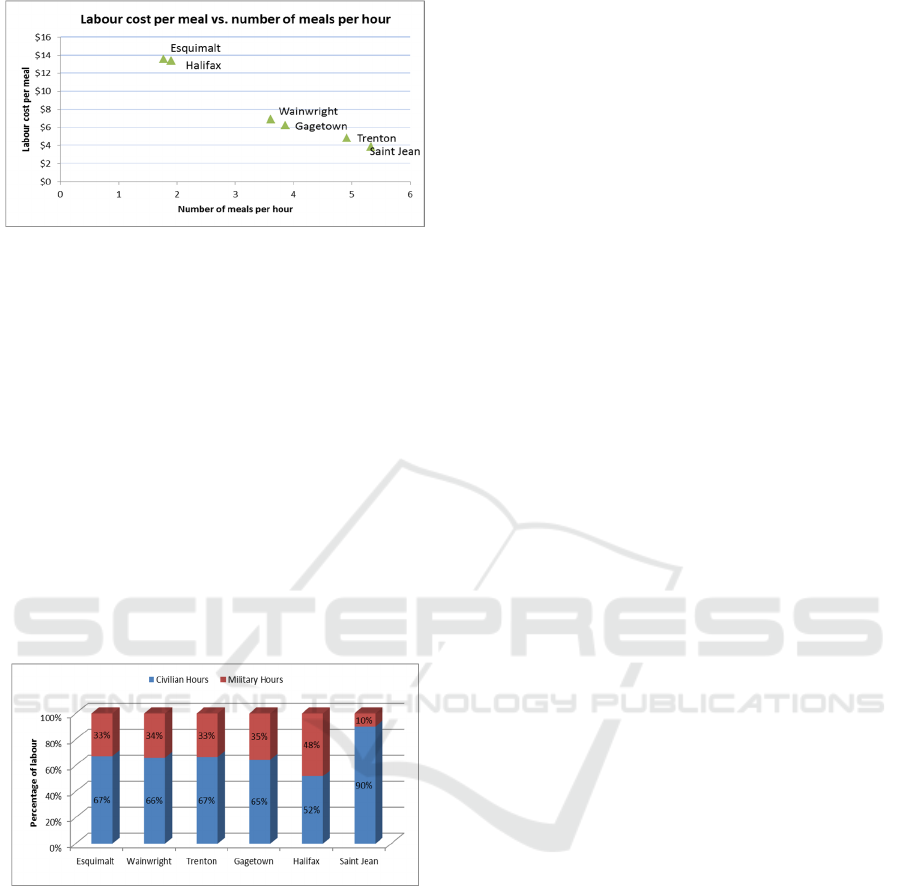

Table 1 shows that labour cost per meal varies

significantly across facilities, which is $3.85, $4.83,

$6.22, $6.89, $13.35 and $13.57 for Saint-Jean,

Trenton, Gagetown, Wainwright, Halifax and

Esquimalt respectively. Some facilities have much

higher labour costs per meal than the others, e.g.,

Halifax and Esquimalt. It needs to be noted that the

food material costs and non-food costs (e.g., cost for

paper plates) are not included in these figures.

Therefore the total cost per meal (including all

labour, food material and non-food costs) should be

even higher. As such, the total cost per meal in some

facilities apparently will not be recoupable by the

payments from the diners.

Table 1: Labour cost per meal by facility.

Facility

# of Total Labour

Saint-Jean 17,883 $68,775 $3.85

Trenton 3,037 $14,678 $4.83

Gagetown 10,613 $65,972 $6.22

Wainwright 4,514 $31,117 $6.89

Halifax 2,161 $28,855 $13.35

Esquimalt 2,335 $31,686 $13.57

SJS Directorate Food Services reported that the

labour rate per hour is the same across CAF Food

Services facilities. Therefore, the labour cost per

meal is mainly influenced by the labour

productivity, i.e., the number of meals per labour

hour. It is intuitive that the more meals per labour

hour produced the less labour cost per meal. Figure

2 shows this negative correlation between the

number of meals per labour hour and labour cost per

meal.

ICORES 2017 - 6th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

220

Figure 2: Labour cost per labour hour and number of

meals per labour hour.

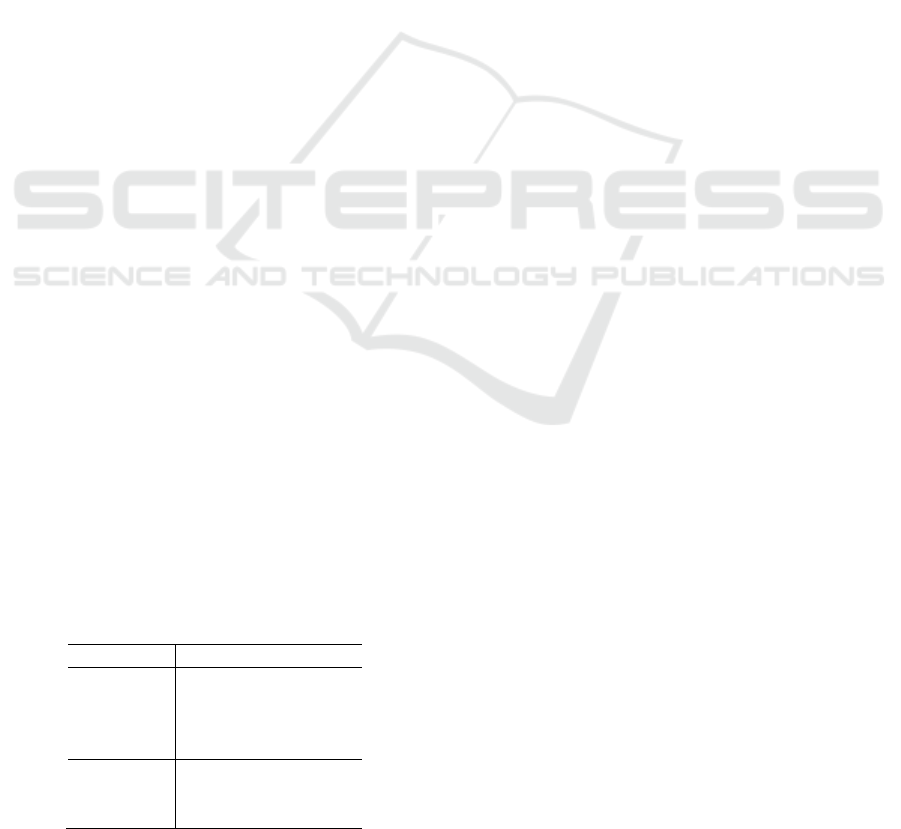

Additionally, since salary difference exists

among different ranks of military cooks and between

military and civilian cooks, the labour cost per meal

will also be influenced by rank composition of

military cooks and civilian and military labour ratio

in the facility (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 shows the percentage of civilian hours

versus military hours in preparing the meals across

facilities. The multiple proportion test shows there is

a significant difference (p-value<0.01) on civilian

military hours ratios among facilities. The figures

for Halifax and Saint-Jean facilities are significantly

different; Halifax uses the least civilian labour

(52%) and Saint-Jean uses the most civilian labour

(90%) among all six facilities.

Figure 3: Percentage of civilian vs. military hours spent on

preparing meals in the six facilities.

All these data have been incorporated in the

calculation of the labour cost per meal in the pilot

study.

3 STUDY DESIGN

Due to the issues identified about the approach taken

to conduct the pilot study, a new study and its

alternative details in study design and method of

analysis are proposed.

3.1 Objective of the Study

The study design is driven and determined by the

objective of the study. Ultimately, CAF Food

Services would like to establish a labour

performance standard that can be used to measure

and compare the measure performance and inform

food services staffing. For this study, as requested, it

will only focus on the quantitative side of the labour

performance, i.e., the labour productivity.

3.2 Two Labour Performance

Standards Should Be Established

With regard to the labour productivity, the first

question is: can we set up a uniform labour

productivity standard for all facilities in CAF Food

Services?

Due to the big variation currently existing on the

labour productivity across facilities (as shown in

Figure 1), we believe it does not make sense to

establish just one labour productivity standard at this

time. Based on the data from the pilot study, it is

recommended two labour performance standards be

established at first:

one labour performance standard for small

facilities (in terms of facilities with small

Volumes of Activity); and

one for large facilities (in terms of facilities

with large Volumes of Activity)

3.3 Choice of Target Population

The target population is the population about which

information is wanted (Cochran 1977). The choice

of the target population should be determined by the

objective of the study. The choice of target

population will profoundly affect the statistics that

result (Lohr & Stratton 2010). Should the target

population be composed of all feeding facilities in

CAF Food Services? The answer is “No”. The

reason is because the objective of this study is to

develop a labour performance standard for the CAF

Food Services not just to get an overall labour

performance measure for CAF Food Services.

Rogers 2014 provides a clear definition of

“standard”: “Standard can refer to an aspect of

performance, or to the level of performance, or to a

combination of both. These standards can be

considered minimum levels required, or levels

required to be considered best practice.” In our

context, the labour performance standard here refer

to the aspect of labour productivity and the level of

the labour productivity; and the standard is

Design a Study for Determining Labour Productivity Standard in Canadian Armed Forces Food Services

221

considered as the best practice in CAF Food

Services. Therefore, to determine the labour

productivity standard for the CAF Food Services, we

do not recommend using the entire CAF feeding

facilities as the target population; instead we

recommend the target population consist of facilities

which represent the best practice in CAF Food

Services in terms of labour performance, i.e., labour

productivity in this study.

Therefore, based on military knowledge about

CAF Food Services, SJS Food Service provided the

following seven facilities to form the target

population, i.e., Saint-Jean, Gagetown, Trenton,

Wainwright, Shilo, Cold Lake and Bagotville. These

facilities were chosen based on the following

considerations:

examples of CAF feeding facilities with good

labour performance, from which the labour

performance standard can be drawn from;

regional consideration (i.e., west, central and

east); and

choice of both operational and training

facilities.

3.4 Suggested Grouping of Facilities

According to the annual Volume of Activity for

FY14/15 obtained from (Whiting and St-Cyr 2015 &

Whiting 2015), these seven facilities have been

classified into two groups (Table 2), i.e., small and

large facility groups. The facility is classified as a

small facility if its annual Volume of Activity is less

than 100,000 meal day (Meal day is another way to

measure the Volume of Activity. One meal day is

equal to three meals.); while the facility is classified

as a large facility if its annual Volume of Activity is

equal to or greater than 100,000 meal days (Record

of Discussion May 2015). Based on these criteria,

Saint-Jean, Gagetown, Trenton and Wainwright are

classified as large facilities while Shilo, Cold Lake

and Bagotville are classified as small facilities.

As described in Section 3.2, two labour

performance standards should be established for

these two groups respectively.

Table 2: Grouping of seven facilities.

Facility Meal days Grouping

Gagetown 267,514 Large

Trenton 127,044 Large

Wainwright 136,269 Large

Saint-Jean 347,940 Large

Shilo 57,590 Small

Cold Lake 69,180 Small

Bagotville 37,260 Small

3.5 Choice of Measure

We agree with (Tremblay 2014) that labour

productivity can be used as a quantitative measure of

food service performance, and the number of meals

per labour hour can be used to measure labour

productivity. In addition to quantitative measures,

qualitative measurer should also be included in

developing the labour performance standard for

CAF Food Services, e.g., customer satisfaction

(mentioned in CAF Food Services Menu 2013 as

well). Both quantitative and qualitative measures

together should form a holistic view of labour

performance in CAF Food Services. However due to

the scope of this study, it was agreed that only the

quantitative side of the labour performance is

investigated in this study.

According to (River 2000), productivity is

defined as a relationship between the total amount of

goods or services being produced (outputs) and the

organizational resources needed to produce them

(inputs). The labour productivity here, i.e., the

number of meals per labour hour, is calculated (see

eqn. (1)) by dividing the total number of meals by

the total number of labour hours spent.

3.6 Suggested Method for Considering

NSCM and How to Define the

Sampling Frame

CAF Food Services cannot easily change the number

of staff in facility solely when the menu changes.

NSCM is a three-week cycle menu; hence each

cycle is composed of 21 days. Over the span of one

year, this cycle will be repeated just a bit more than

17 times. To simplify the study and to take budget

constraints into consideration, it should be assumed

that the 17 cycles are the same. Therefore, we should

be able to focus the future labour study within one

cycle. Hence, a random sample should be drawn

from 21 days, just a full cycle of NSCM; and the

order and dates of on-site visits should be randomly

selected.

The sampling frame for this study should be a

list of consecutive dates between the study starting

date and the 21

st

date that follows the starting date.

Once SJS Directorate Food Services determines the

start date of the data collection for the future labour

study, the sampling frame can be determined

immediately.

ICORES 2017 - 6th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

222

3.7 Suggested Sampling Method

In order to reflect real operations, randomization of

the dates for on-site visits is necessary and

important. The dates should be randomly selected

and should not be revealed to the facility in advance.

Further exploration shows the variation within

each individual facility on labour productivity is

smaller relatively to the variation between facilities.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used

to test the between and within facility variation on

labour productivity (See Table 3), i.e., number of

meals per labour hour (data from Table A).

Therefore, instead of a simple random sampling,

a stratified random sampling method can be used.

Each facility should be treated as a stratum in both

small and large facility groups. The stratified

random sampling should be conducted in the

following steps:

First, clearly specify the strata (each facility is

treated as a stratum);

Then, within each stratum (i.e., each facility),

use a simple random sampling method to

select a random sample of days from the

established sampling frame for the on-site

visit;

Collect data from each visit and calculate the

labour productivity for each facility; and

Pool the results from all facilities (i.e., all

strata) within the group (large or small) to get

an overall labour productivity measure for the

group.

The advantages of this stratified random

sampling method are:

separate estimates can be obtained for each

stratum (i.e., each individual facility) without

additional sampling; and

since the data are more homogeneous within

each stratum, the stratified sampling estimator

usually has smaller variance than the

corresponding simple random sampling

estimators from the same sample size, i.e., a

stratified sample can provide greater precision

than a simple random sample of the same size.

3.8 Sample Size and Sample Allocation

In order to do sampling, the sample size and sample

allocation should be determined first. The following

definitions are used in this determination. Noted

here, as mentioned in Section 3.7, each facility is

treated as a stratum in the following calculation.

T

total number of facilities in large or

small facility group

total number of units in the

facility,1,2,…,

total number of units in all facilities

number of samples for the

facility,1,2,…,

the total sample size for all facilities

the proportion of the sample which

will be allocated to the

facility

cost of obtaining a sample from the

facility

standard deviation for the

facility

mean for large or small facility

group

Variance for the mean of the large

or small facility group

mean for

facility in large or

small facility group

the upper 0.025 (i.e., 0.05/2) critical

point of the standard normal

distribution

What is the sample size for estimating mean

labour productivity for the large or small facility

group to within some margin of error (noted as b)

with 95% probability? This question can be

translated into eqn. (2):

Table 3: Between and within group variation.

Sum of Square f Mean Square F Significance

Between Groups 54.228 5 10.846 35.992 .000

Within Groups 7.232 24 0.301

Total 61.460 29

Design a Study for Determining Labour Productivity Standard in Canadian Armed Forces Food Services

223

/

(2)

Since the Stratified Random Sampling method is

used and the samples are drawn independently from

the strata, an unbiased estimator of the sample

variance (

for the large or small facility group

can be calculated using eqn. (3) (Cochran 1977):

1

(3)

where

.

Replacing

in eqn. (2), eqn. (2) is changed to

1

(

4

)

Solving this margin of error equation for leads to:

∑

∑

(5)

Using this equation and based on data obtained from

the large or small facility group from the pilot study,

the total sample size , required for estimating mean

labour productivity to within some margin of error b

with 95% probability can be calculated for the large

and small facility groups respectively (see Annex

B).

However, there is still one parameter

which

needs to be determined. The variable

represents

how the sample is allocated to the

stratum. There

are several ways to allocate the sample (Cochran

1977, Lohr & Stratton 2010, Montgomery &

Stratton 2010); the following allocation scheme is

recommended:

/

∑

/

(6)

/

∑

/

(

7

)

This allocation scheme was chosen based on the

following considerations:

larger sample size should be assigned to strata

containing larger number of elements

(i.e., larger

;

larger sample on less homogeneous strata (i.e.,

larger

); and

smaller samples from strata with higher cost

(i.e., higher

).

In summary, the equations above provide not

only the calculation of total sample size but also the

sample size allocation.

To be conservative and to consider the data

obtained from a less ideally designed pilot study, the

sample sizes determined based on the pilot data have

been inflated to the next integer (see Annex B).

It needs to be noted in the pilot study, the small

facility group was formed by two small facilities,

i.e., Halifax and Esquimalt. Unfortunately, Cold

Lake, Shilo and Bagotville were not included in the

pilot study. Due to insufficient data for Shilo, Cold

Lake and Bagotville from the pilot data and to get a

more robust estimation, the pooled

from the small

facility group in pilot study (i.e., Halifax and

Esquimalt) was used for Cold Lake, Shilo and

Bagotville. The detailed sample size calculation and

sample allocation can be found in Annex B. In

summary, for large facility group, 16 random

samples are needed in total. The number of samples

allocated for Wainwright, Trenton, Saint-Jean and

Gagetown are 4, 5, 3 and 4 respectively. For small

facility group, 13 random samples are needed in

total. The sample size for Bagotville, Shilo and Cold

Lake are 5, 4 and 4 respectively.

3.9 Suggested Method to Determine the

Labour Productivity

Once the data for the selected facilities are collected,

the labour performance measurer (i.e., labour

productivity) and its variance can be determined.

Two sets of labour productivity will be

determined: one for large facility group and one for

small facility group. The pooled labour productivity

for the large/small facility group can be calculated

using a weighted average of the labour productivities

(i.e., number of meals per labour hour) across

selected facilities within the large/small facility

group (see eqn.(8)). The weights individual facility

(i.e., individual stratum) receiving is

/

. As

(Cochran 1977) pointed out this self-weighting

scheme is time-saving. The same weighting scheme

is used for calculating the variance for the estimated

pooled labour productivity (see eqn. (9)).

1

⋯

(

8

)

1

⋯

1

(

9

)

ICORES 2017 - 6th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

224

As discussed earlier in Section 3.3, specifically

in our context, the labour performance standard

refers to the aspect and the level of labour

productivity; and the standard is considered as the

best practice in CAF Food Services. As these labour

productivity measures are generated from the

selected CAF Food Service facilities of best

practice, the labour productivity generated from the

next labour study can be considered as the initial

standard. It needs to be noted that establishing the

labour performance standard will be an evolving

process. Although the current study does not

produce a labour performance standard directly, it is

significant since it is one of the building blocks in

the early stage which will support the establishment

of the first labour performance standard for CAF

Food Services.

4 CONCLUSIONS

4.1 Summary

This paper first reviews the results from the pilot

study conducted in February and March 2015 for

CAF Food Services. Due to the issues identified

with the pilot study, this report also proposes a

revised design and analytical approach for a follow-

on study.

In summary, the target population is composed

of two groups, i.e., the large facility and small

facility groups. The large facility group consists of

Wainwright, Trenton, Saint-Jean and Gagetown; and

the small facility group consists of Bagotville, Shilo

and Cold Lake. These are chosen as facilities of best

practice on labour performance based on military

knowledge and judgement. A stratified random

sampling method is suggested being used to get the

random samples for the target population. With the

same sample size, a study with a stratified random

sampling scheme will be able to produce a more

precise estimator compared to that with a simple

random sampling scheme. The sample size and

sample allocation have been determined based on

the data obtained from the pilot study. In summary,

for the large facility group, 16 random samples are

needed in total. The number of samples allocated for

Wainwright, Trenton, Saint-Jean and Gagetown are

four, five, three and four respectively. For the small

facility group, 13 random samples are needed in

total. The sample size for Bagotville, Shilo and Cold

Lake are five, four and four respectively. The

approach for calculating weighted stratified random

sample estimates and their corresponding variances

are also determined for the future study.

Although according to the client’s request, this

study focuses only on the quantitative side of the

labour performance, we believe in order to provide

the labour performance standard for CAF Foods

Services, not only the quantitative measure, but also

qualitative measure of labour performance should be

considered. Therefore, if it is financially permitted,

we recommend that a social study (using techniques,

e.g., customer surveys, interviews, or focus groups)

be conducted to measure the qualitative aspects of

the labour performance. Only focusing on the labour

productivity may drive the facilities to pursue fast

but not high quality food services.

4.2 Significance of the Study

Unlike most of the other food industries, CAF Food

Services is not profit driven and fulfilling the

operational needs is its first priority. Given that the

CAF Food Services does not have a labour

performance standard, establishing one is

significant.

It is beneficial to provide a labour performance

standard (i.e., level of labour performance of best

practice here) against which a performance of a CAF

Food Services facility can be measured and

compared. Once developed, this labour performance

standard could then be used to ensure food service

facilities to provide efficient and effective food

service support to the CAF and may inform future

rationalization of staffing within CAF Food

Services. Routine measurement of labour

performance could also provide a way for CAF Food

Services managers to monitor and track operational

improvements over time. This study focuses on the

quantitative side of the labour performance, i.e.,

labour productivity. As summarized in (River 2000),

productivity measures can play a key role in

business process redesign and optimization,

assessing maximum sustainable outputs, lowering

products or service unit cost, and exploring the

feasibility of out sourcing.

Developing a labour performance standard will

be an evolving process. Although the current study

does not produce a labour performance standard for

CAF Food Services directly, it outlines the requisite

study design for data collection and an analytical

approach for a future study, which will underpin

future development of a labour performance

standard for CAF Food Services.

Design a Study for Determining Labour Productivity Standard in Canadian Armed Forces Food Services

225

REFERENCES

Request for Operational Research and Analysis:

Performance Measure in CAF Food Services, Mat J4 /

D Food Services, December 2014.

Definition related to the CAF Food Services, Maj Mike

Whiting, Communication on 8 December 2015.

Meeting on Request for Operational Research and.

Analysis, Maj Mike Whiting and Manchun Fang, on 18

December 2014.

Collection Tool-Labour Study, Maj Mike Whiting,

Communication on 19 January 2015.

Using Labour Productivity as a Food Services

Performance Measurement and Human Resources

Management Tool, ADM (Mat) Food Services,

Roland Tremblay, 2004.

Sampling Techniques, William G. Cochran, John Wiley &

Sons, Inc. 1977.

Sampling: Design and Analysis, Sharon L. Lohr and

Richard Stratton, ISBN 10:0-495-10527-9, 2010.

Standards, evaluative criteria and benchmarks, Better

Evaluation, Patricia Rogers, Professor of Public Sector

Evaluation, RMIT University. Melbourne. March

2014.

Annual Meal Day, Provided by Mark Whiting and Guy St-

Cyr, SJS Food Service, Communication on 24 July 2015.

Meal days for FY 13/14 and FY 15/16, Provided by Maj

Mark Whiting, Communication on 10 June 2015.

Record of Discussions for meeting between DMGOR and

SJS D Food Services, 28 May 2015.

Financial Management, Accounting Standard and

Procedures, CAF Food Service Manual, A-85-269-

001/FP-001, Nov 2013.

Modern Management. 8th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ:

Prentice Hall Publishing, Certo SC. 2000.

Design and Analysis of Experiments, D.C. Montgomery,

Richard Stratton, 2010.

Costing Sheet for Travel for Future Labour Study, Maj

Mark Whiting, Communication on 8 June 2015.

ANNEX A: SUMMARY OF DATA

FROM PILOT STUDY

Table A: Summary statistics for Halifax obtained from the pilot study.

Facility Day

Civilian

Hours

Military

Hours

Civilian

Wages

Military

Wages

Total

Hours

Labour

Costs

# of

Meals

Meals/Hour

Halifax

D1 24 143 $615 $4086 167 $4701 483 2.9

D2 120 90 $2502 $2688 210 $5191 496 2.4

D3 152 143 $3216 $4157 295 $7373 444 1.5

D4 144 90 $3084 $2688 234 $5773 398 1.7

D5 136 98 $2901 $2917 234 $5818 340 1.5

Gagetown

D1 334 158 $6875 $4778 492 $11653 2180 4.4

D2 342 203 $7058 $5977 545 $13034 2272 4.2

D3 396 225 $8276 $6618 621 $14894 2224 3.6

D4 348 218 $7215 $6404 566 $13619 2266 4.0

D5 326 203 $6810 $5962 529 $12773 1671 3.2

Saint-Jean

D1

614 83 $12,122 $2,534 697 $14,656 3816 5.5

D2

630 68 $12,130 $2,106 698 $14,236 3556 5.1

D3

606 68 $11,640 $2,106 674 $13,747

3606 5.4

D4

556 53 $10,523 $1,664 609 $12,187 3523 5.8

D5

620 60 $12,057 $1,892 680 $13,950 3382 5.0

Wainwright

D1

168 90 $3,738 $2,745 258 $6,484 992 3.8

D2

168 83 $3,738 $2,517 251 $6,255 1051 4.2

D3

192 83 $4,269 $2,517 275 $6,786 704 2.6

D4

136 90 $2,992 $2,617 226 $5,610 963 4.3

D5

152 90 $3,365 $2,617 242 $5,983 804 3.3

Trenton

D1

104 30 $2,217 $799 134 $3,016 558 4.2

D2

80 45 $1,825 $1,170 125 $2,995 715 5.7

D3

80 53 $1,825 $1,384 133 $3,209 650 4.9

D4

72 45 $1,610 $1,226 117 $2,836 603 5.2

D5

72 38 $1,610 $1,013 110 $2,622 511 4.7

ICORES 2017 - 6th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

226

Table A: Summary statistics for Halifax obtained from the pilot study (Cont.).

Facility Day

Civilian

Hours

Military

Hours

Civilian

Wages

Military

Wages

Total

Hours

Labour

Costs

# of

Meals

Meals/Hour

Esquimalt

D1

200 60 $4,400 $1,658 260 $6,058 435 1.7

D2

176 83 $3,870 $2,271 259 $6,141 408 1.6

D3

176 120 $3,870 $3,267 296 $7,137 426 1.4

D4

152 98 $3,457 $2,668 250 $6,124 365 1.5

D5

168 90 $3,830 $2,397 258 $6,227 701 2.7

ANNEX B: SAMPLING

As we discussed in Section 3.8, the sample size and

sample allocation will be determined using eqns. (5),

(6) and (7).

The following sample size calculation and

sample allocation are based on the information from

the pilot study or provided by (Whiting June 8

2015). The number of the total observation units is

21 (a three-week full cycle of NSCM). For the large

facility group:

Wainwright (i.e.,i1)

–

N

21, σ

0.71, c

2.4c

– Using eqn. (6), the weight for Wainwright

is calculated:w

0.33

Trenton (i.e.,i2)

– N

21,σ

0.58,c

c

– Usingeqn.6,theweightforTrenton

iscalculated:w

0.27

Saint-Jean (i.e.,i3)

– N

21,σ

0.32,c

c

– Usingeqn.6,theweightforSaint‐

Jeaniscalculated:w

0.15

Gagetown (i.e.,i4)

– N

21,σ

0.50,c

1.9c

– Using eqn. 6, the weight for

Gagetowniscalculated:w

0.24

In the pilot study, the small facility group was

formed by two small facilities, i.e., Halifax and

Esquimalt. However it was determined later that

these three facilities, i.e., Cold Lake, Shilo and

Bagotville would be good examples of small feeding

facilities in terms of labour performance.

Although there was no data collected for these

three small facilities, there is no problem to figure

out the

and

for Cold Lake, Shilo and

Bagotville. To get a more robust estimation, the

pooled standard deviation from Halifax and

Esquimalt was used for Cold Lake, Shilo and

Bagotville; therefore, the standard deviation for all

three small facilities are computed to be, and

assumed to be identical.

For the small facility group:

Cold Lake (i.e.,i=1)

– N

21,σ

0.58,c

1.5c

– Usingeqn.6,theweightforTrenton

iscalculated:w

0.34

Shilo (i.e.,i2

– N

21,σ

0.58,c

1.7c

– Usingeqn.6,theweightforTrenton

iscalculated:w

0.32

Bagtoville (i.e.,i3

– N

21,σ

0.58,c

1.5c

– Usingeqn.6,theweightforTrenton

iscalculated:w

0.34

Let 0.25 (initial determined, can be justified

as required) and 1.96 (is the 97.5% percentile of

the standard norm distributions, the critical value for

95%), and according to eqn. (5), the sample size

required is approximate 14.59 for estimating the

mean of labour performance productivity for the

large facility group with 95% probability with

marginal error 0.25. Applying the corresponding

weights, the sample allocation is calculated for each

individual facility as follows:

Wainwright: nw

3.864

Trenton: nw

4.905

Saint-Jean: nw

2.743

Gagetown: nw

3.094

It needs to be noted that to be conservative and to

consider the less ideal design of the pilot study, the

sample sizes determined based on the pilot data have

been inflated to the next integer. Therefore, the

number of samples allocated for Wainwright,

Trenton, Saint-Jean and Gagetown are 4, 5, 3 and 4

respectively.

The same procedure is used for calculating the

sample sizes for the small facility group. Calculating

based on eqn. (5), the total sample size of 12.44 will

be required. Again, for the same reason, the sample

size determined based on the pilot data via optimal

allocation scheme have been inflated to the next

integer. Therefore, the sample size for Bagotville,

Shilo and Cold Lake are 5, 4 and 5 respectively:

Bagotville: nw

4.275

Shilo: nw

3.994

Cold Lake: nw

4.175

Design a Study for Determining Labour Productivity Standard in Canadian Armed Forces Food Services

227