Identifying Objectives for a Learning Space Management System with

Value-focused Thinking

Ari Tuhkala

1

, Hannakaisa Isom

¨

aki

1

, Markus Hartikainen

1

, Alexandra Cristea

2

and Andrea Alessandrini

3

1

Faculty of Information Technology, University of Jyv

¨

askyl

¨

a, P.O. Box 35, Jyv

¨

askyl

¨

a, Finland

2

Department of Computer Science, University of Warwick, Coventry CV47AL, U.K.

3

Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, University of Dundee, Perth Road, Dundee DD14HT, Scotland

Keywords:

Classroom Management, Educational Technology, Special Education, Value-focused Thinking.

Abstract:

A classroom with a blackboard and some rows of desks is obsolete in special education. Depending on the

needs, some students may need more tactile and inspiring surroundings with various pedagogical accessories

while others benefit from a simplified environment without unnecessary stimuli. This understanding is applied

to a new Finnish special education school building with open and adaptable learning spaces. We have joined

the initiative creation process by developing software support for these new spaces in the form of a learning

space management system. Participatory design and value-focused thinking were implemented to elicit the

actual values of all the stakeholders involved and transform them into software implementation objectives.

This paper reports interesting insights about the elicitation process of the objectives.

1 INTRODUCTION

The traditional classroom setting of children sitting

on benches and patiently listening to a teacher is not

easily applicable in special education. The class-

rooms are often less inspiring, and an activity-driven

approach is more appropriate (

¨

Ozen and Ergenekon,

2011). For example, children with hearing and vision

problems can benefit from visual and physical stim-

ulations and moving between different spaces, and

children with autism disorders benefit from the use

of technologies and digital artefacts that promote col-

laborative educational activities and attentional exer-

cises (Alessandrini et al., 2014). To overcome these

issues, a new school was recently created in Finland,

the Valteri School Onerva, which was just finished in

early 2016. Its stated goal was to enable functionality,

physical activity, and the application of new technolo-

gies. The idea of an open and adaptable school was

a focus from the planning and construction stages of

the school.Under this concept, all physical spaces are

understood as potential spaces for learning, not just

the classroom, and the environment is dynamically

adapted to the needs of the practised pedagogy. A

simple example is using stairways as an active learn-

ing space: children might physically move from one

stairway step to another while learning the number

line, months, or weekdays (Ikkel

¨

a-Koski, personal

communication, May 5, 2014).

However, the activities in the modern school en-

vironment of the Valteri School Onerva must be sup-

ported with modern technology. In the stairway ex-

ample, in a regular educational setting, with the cur-

rent level of support, it would not be possible to know

if the stairway was already in use, as the stairway is a

non-traditional learning space and would not be con-

sidered by any scheduling tool. The lack of such criti-

cal information prevents teachers from implementing

such new pedagogical ideas, even simple ones due to

the time costs if the targeted space is not available and

the whole class must return to the classroom. More-

over, not all teachers have the time and resources to

develop new ideas and surely are not aware of all the

available possibilities. Unfortunately, we find the cur-

rent facility (or classroom) management systems not

suitable for use in this dynamic environment. The

systems for commercial or non-commercial organisa-

tions seem to be developed mainly for standard ad-

ministrative needs. Instead of traditional facility man-

agement features, teachers need a tool that supports

them in organising flexible pedagogical activities and

sharing pedagogical practices. To successfully de-

velop a learning space management system, we need

to carefully examine the objectives that teachers asso-

Tuhkala, A., Isomäki, H., Hartikainen, M., Cristea, A. and Alessandrini, A.

Identifying Objectives for a Learning Space Management System with Value-focused Thinking.

DOI: 10.5220/0006230300250034

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) - Volume 1, pages 25-34

ISBN: 978-989-758-239-4

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reser ved

25

ciate with the open and adaptable environment.

As a result, the requirements for a learning space

management system were produced in the ONSPACE

research project between May 1 and December 5,

2014, before the building construction even started.

Requirements elicitation is one of the most critical ac-

tivities of software development and is known to be a

major reason for project failures (Pacheco and Gar-

cia, 2012). We grounded our research in two assump-

tions: First, to get a better understanding of teachers’

work, we needed to involve our stakeholders and ar-

range user-centred workshops based on participatory

design principles. Participatory design emphasises

shared decision-making, which is crucial when dif-

ferent stakeholders are involved (Frauenberger et al.,

2015). Second, traditional requirements elicitation

concentrates on identifying system’s goals, function-

ality, and limitations (Pacheco and Garcia, 2012).

While this is fundamental, we argue that the stake-

holders’ objectives need to be defined more holisti-

cally than just considering the actual system. There-

fore, we applied a method developed by Profes-

sor Ralph Keeney and proposed in the book Value-

focused Thinking: A Path to Creative Decision Mak-

ing (1992). The method offers systematic guidelines,

which are described in a later section, for identifying

objectives for the defined decision problem.

This study has both methodological and practical

contributions. Value-focused thinking has been ap-

plied in multiple domains, but less in the context of

requirements elicitation, especially as they relate to

education. Learning space management systems are

currently gaining attention as modern schools increas-

ingly adjust to the idea of open and adaptable learning

environments (Sanoff and Walden, 2012). The iden-

tified objectives were used during implementation of

the learning space management prototype. To fulfil

our goals, we framed the following research ques-

tions:

• How can value-focused thinking be implemented

and applied to the requirements elicitation con-

text?

• What are the objectives associated with an open

and adaptable environment?

For the first question, we describe in detail how

we applied the method, and for the second, we inter-

pret recordings from the workshops and present the

identified objectives. The original requirements spec-

ification document is in Finnish and consists of 32

pages; therefore, its full inclusion is beyond the scope

of this paper. Instead, we highlight and discuss the

process of extracting the objectives, followed by a dis-

cussion of the objectives. The prototype of the system

was developed in 2015, in the sequel project called

ONSPACE2, and the objectives were used as guid-

ing evaluation principles by software engineers dur-

ing development of the learning space management

system.

2 APPROACHES FOR USER

PARTICIPATION AND

INVOLVEMENT

User participation and involvement are considered

essential for success in system development (Barki

and Hartwick, 1994; He and King, 2008; Mahmood

et al., 2000), as they improve the quality of the sys-

tem by generating more precise requirements (Har-

ris and Weistroffer, 2009) and tend to lead to a pos-

itive attitude and perceived usefulness among users

(Abelein and Paech, 2015; McGill and Klobas, 2008).

Participation refers to assignments, activities and be-

haviours that users engage in during the system devel-

opment process and involvement is a psychological

state of the individual, defined as the importance and

relevance of a system to a user (Barki and Hartwick,

1994). User involvement can also be seen as a broader

concept, in which users are somehow involved in the

system’s development process, whereas user partici-

pation refers to more active and intentional involve-

ment (Iivari et al., 2010).

Kujala (2003) has presented methodological ap-

proaches to achieving participation and involvement

(Table 1). In user-centred design, ethnology, and con-

textual design, participation can be characterised as

an approach by the designer to gain information from

participants. The fundamental difference in partici-

patory design is that it encourages participants to ac-

tively take part in the decision making and creative

processing of the solution (Frauenberger et al., 2015).

The goal of participatory design is not just to em-

pirically understand the design activity (or users, as

in user-centred design), but to simultaneously envi-

sion, shape, and transcend it to benefit the participants

(Spinuzzi, 2005).

The ideological grounding of participatory design

emerged from Scandinavian workplace democracy to

ensure that people who are affected by technology can

also participate in making decisions about it (Bjerk-

nes and Bratteteig, 1995; Ehn, 1988; Halskov and

Hansen, 2015; Muller and Kuhn, 1993). In partic-

ipatory design, the following statements are under-

stood as guiding principles: participants from diverse

backgrounds are seen as experts in how they live their

lives and design in collaboration with other profes-

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

26

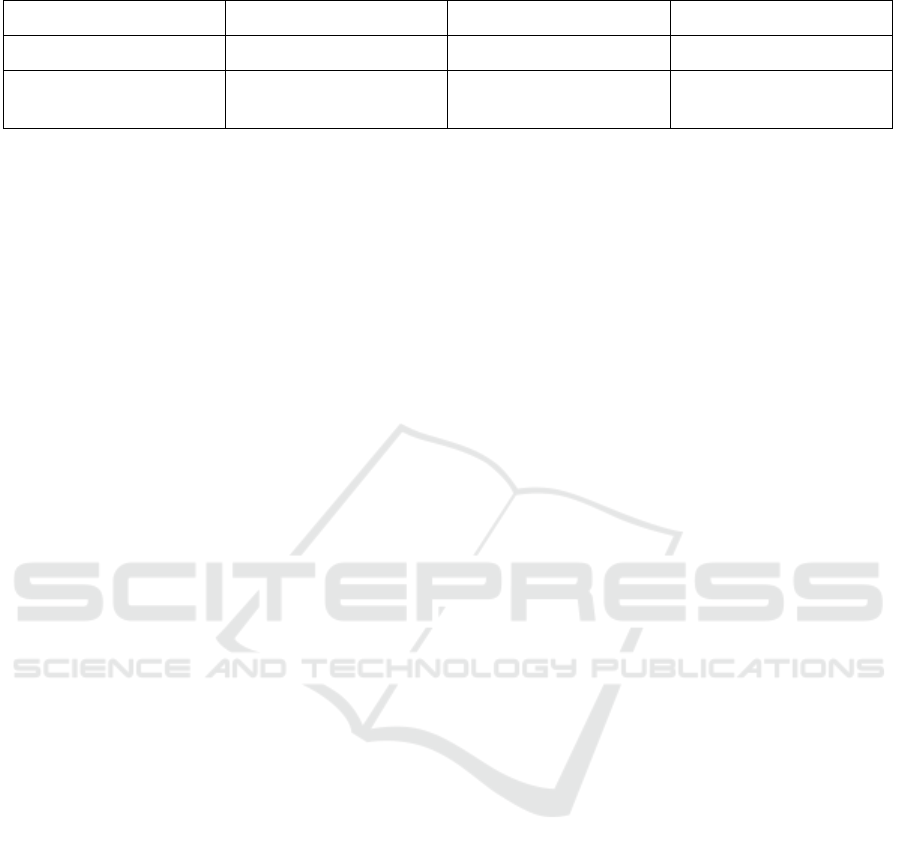

Table 1: Methodological approaches to achieve participation and involvement (Kujala, 2003).

Participatory design User-centered design Ethnography Contextual design

Democratic participation Usability Social aspects of work Context of work

Workshops, prototyping Task analysis, prototyp-

ing, usability evaluations

Observation, video anal-

ysis

Contextual inquiry, pro-

totyping

sionals (Sanders et al., 2010; Sanoff, 2007), partic-

ipants have the right to influence technological de-

cisions affecting their private and professional lives

(Bergvall-K

˚

areborn and St

˚

ahlbrost, 2008), and espe-

cially, participatory design is seen as appropriate in

the context of special needs (Benton et al., 2014;

Frauenberger et al., 2011; Guha et al., 2008; Malin-

verni et al., 2014). Thus, we have based our work-

shops on participatory design to adopt these principles

and we have implemented value-focused thinking as

a requirements elicitation technique.

3 VALUE-FOCUSED THINKING

Value-focused thinking (VFT) comes from the opera-

tional research field and has been applied to decision

problems in multiple domains, such as defence, en-

vironment, energy, government, corporations, and in-

telligence (Parnell et al., 2013). The underlying prin-

ciple of VFT is that when faced with a decision prob-

lem, participants should first examine their values. In

general, values are core concepts within individuals

and society (Williams, 1979). Values are desirable

and trans-situational goals that serve as principles that

guide one’s lives (Friedman, 1996; Schwartz, 1992).

Keeney (1992; 1996) employs values as principles for

evaluation of actual or potential consequences of ac-

tion or inaction, of proposed alternatives, and of made

decisions. In VFT, decision makers reflect what they

want to achieve instead of immediately comparing al-

ternative solutions. Values are made explicit for ex-

amination by associating them with a specific state-

ment of objectives, which are in the form of a verb fol-

lowed by an objective (Keeney, 1992; Keeney, 2013).

The basic steps of the VFT process are as follows:

develop a list of values, convert values to objectives,

and classify them as a means-ends objective network

(Sheng et al., 2005; Sheng et al., 2010). The start-

ing point is the statement of the problem to be solved.

The definition of the problem must be made carefully

to ensure a shared understanding of the situation. Par-

ticipants are asked to make a list of anything that he

or she hopes to achieve by solving the problem being

addressed. This is done without any restrictions or

constraints in reflection, to reach the different dimen-

sions that participants find valuable. After generating

the initial list, participants are encouraged to extend

the list using different mind-probing techniques (Ta-

ble 3 in Keeney, 1996) . For example, participants

can be asked to review each item and articulate why

they care about it, which in turn might lead to new

items. This phase of producing a comprehensive list

requires intensive thinking and discussion, and it will

most likely take several iterations.

The list is considered as completed when partici-

pants cannot find any new information about the prob-

lem. Then, each list item is translated into the format

of objectives (Keeney defines this phase as convert-

ing values into a common form). For example, if the

participants expressed that the school day is too busy,

the item might be ’rush’, and the objective would be

’reduce rush’. This might raise discussion, why there

is the rush and how it could be reduced. This, in turn,

may lead to new items and objectives. Finally, the list

should be examined for possible redundancies.

The next phase is to structure objectives as funda-

mental and means objectives. Fundamental objectives

characterise the essential interests in the decision sit-

uation representing the goals that participants value.

Means objectives are of interest due to their impli-

cations for the degree to which fundamental objec-

tives can be achieved. For example, if reducing rush

is a fundamental objective, means objectives could be

about having needed accessories available. Finally,

the structure of these objectives is illustrated by build-

ing a means-ends network demonstrating how the dif-

ferent objectives are related to each other. The process

of structuring objectives results in a deeper and more

accurate understanding of what one cares about and

helps to clarify the decision context and enhances the

quality of decisions.

4 METHODOLOGY

This section presents the stakeholder organisation, de-

scribes the data gathering process and explains how

data was analysed.

Identifying Objectives for a Learning Space Management System with Value-focused Thinking

27

4.1 Stakeholder Description

The Valteri School Onerva is one of the six learning

and consulting centres of Valteri schools that oper-

ate under the Finnish National Board of Education.

The school provides services that support learning

and school attendance in order to implement general,

intensified, and special support. In the school, edu-

cation is combined with rehabilitation and guidance

that support learning to form a seamless whole. The

school has expertise particularly in supporting needs

relating to vision, hearing, language, and interaction.

The school’s mission is to increase the accessibil-

ity of support services and promote the neighbour-

hood school principle. The school aims to realise

this, by making their operations more effective, creat-

ing new action models and innovations, and utilising

new technology. The aim is to develop solutions for

learning and rehabilitation that support learning for

individuals. The school’s activities are guided by a

development-oriented approach and the utilisation of

research and networking.

4.2 Data Gathering

We organised four workshops (Table 2) with the

school’s staff. The data was collected by recording

the workshops with a video camera or mobile phone;

the researchers also took notes. The participants

were special education teachers, occupational thera-

pists, visual sense specialists, and researchers. The re-

searchers who participated in the workshops were all

from the University of Jyv

¨

askyl

¨

a, Faculty of Informa-

tion Technology. There was some variation between

workshops: in the first workshop there was one per-

son from the technical staff, and in the last workshop

there were two members of the instructional staff, but

otherwise, the membership stayed constant. All of the

workshops were held in the old school’s facilities to

help researchers understand the context at the given

time and provide teachers and staff members with fa-

miliar surroundings.

The first workshop acquainted the participants

with one another and familiarised everyone with the

context of our study. Ininformal group discussions

were conducted, during which we asked questions

about the new school building, elicited their ideas of

an open and adaptable environment, and discussed the

initial need for the learning space management sys-

tem. The technical staff member presented a three-

dimensional (3D) model of the new school building,

and researchers analysed it together with the partici-

pants. The researchers produced conceptual maps of

the building to gain a better understanding of the new

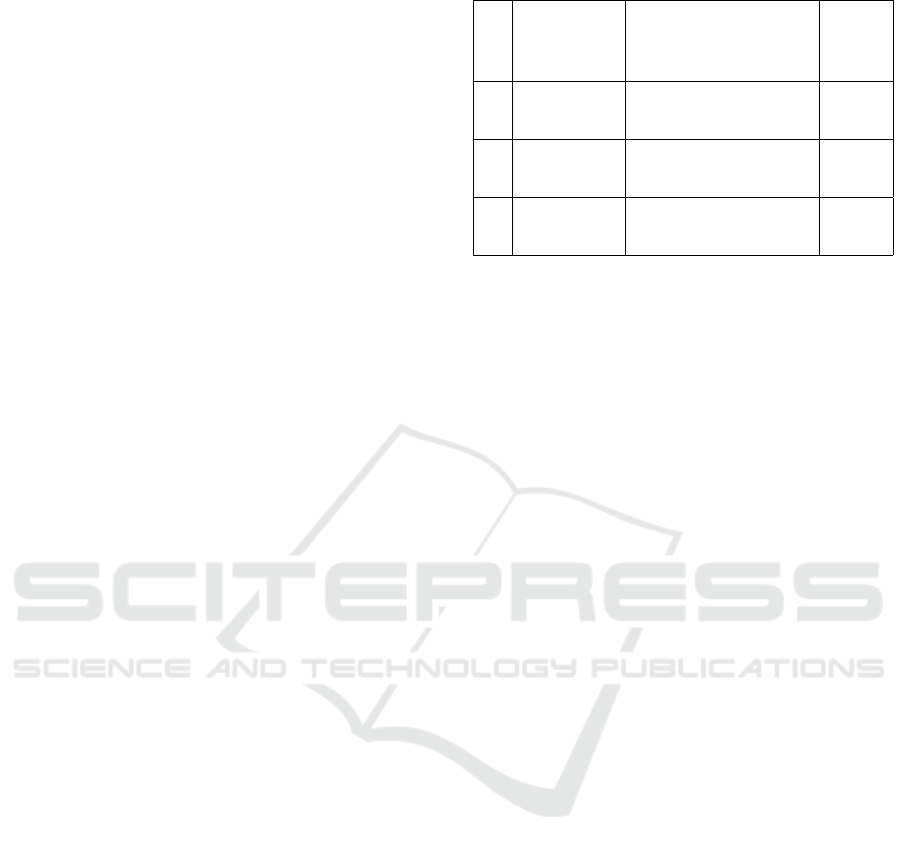

Table 2: Workshops in the study.

1. 14.5.2014 8 teachers, 1 tech-

nical staff, 3 re-

searchers

Video

2. 24.8.2014 6 teachers, 4 re-

searchers

Video

3. 27.9.2014 6 teachers, 3 re-

searchers

Audio

4. 12.12.2014 6 teachers, 2 instruc-

tors, 3 researchers

Video

environment. Finally, the participants discussed the

initial desired functions and the possible users of the

system.

In the second workshop, the participants were

asked to provide ideas that they associate as impor-

tant with the open and adaptable environment. The

intensive discussion resulted in a list of words which

described anything that the participants perceived as

valuable in the school context. The list was reviewed

and discussed, and the participants defined higher

level categories for each item. Finally, the partici-

pants transformed the items into objectives represent-

ing their shared understanding of how the item could

be achieved. The objectives were examined together

to remove redundancy and disentangle abstract objec-

tives into more concrete ones. The emerging objec-

tives were scrutinised by asking the participants ’why

this item is important’. The goal of this back-and-

forth process was to encourage more elaboration of

the objectives. Because limited time was available

during the workshop, the participants finished the task

by themselves, and they sent the final document by

email to the researchers.

4.3 Producing Functional Requirements

The analysis of the first two workshops was based on

VFT methodology. First, the recordings were checked

to ensure that there was no missing data and to sup-

port the researchers’ notes taken during the discus-

sion. The document then included a full list of ob-

jectives. When analysing the objectives, we found

that some of them were directly related to the actual

system and others related to the whole organisation.

Therefore, the objectives were divided into two cat-

egories: system objectives and organisational objec-

tives. From the system objectives, we derived the ini-

tial functions of the system and illustrated them as a

use case diagram. Every use case was then described

in use case scenarios, which detailed how the user in-

teracts with the system.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

28

In the third workshop, the researchers described

to participants how the use case diagram was con-

structed and how the system would be used by de-

scribing the use case scenarios. Furthermore, the re-

searchers presented initial user profiles, system archi-

tecture, and non-functional requirements. The partic-

ipants then discussed the requirements and gave feed-

back on how they could be enhanced. After the work-

shop, the requirements were updated using the feed-

back from the participants. The final version of the

document was sent to the participants two weeks be-

fore the final meeting, in December 2014. In the last

meeting, participants evaluated the outcomes and val-

idated the produced requirements. The participants

appreciated the transparency of the design process

and how researchers were able to communicate us-

ing language they understood. Finally, researchers

thanked the participants for their collaboration and

discussed future plans for the prototype development.

4.4 Identifying Objectives

The recordings of the four workshops were tran-

scribed in order to gain an overall view of data,

which were then exported into the ATLAS-ti software

for more detailed interpretation. Data was analysed

through a process of open coding (Corbin and Strauss,

1990) to develop a list of quotations that related to the

objectives of the group, that is, what the group con-

sidered important or how the desired situation could

be achieved. All 153 quotations were examined one

by one and assigned at least one code. The coding

process was overlapping: a single quotation could be

connected to many different codes and vice versa. If

it was impossible to connect a quotation with any of

the previous codes or imagine a new code, the quota-

tion was removed as an irrelevant phrase. Finally, 133

quotations remained that had been assigned at least

one code. The rejected quotations were examined to

ensure that no relevant data was removed.

The quotations inside the codes were refined to as-

certain that the codes had a coherent structure. The

codes, including the assigned quotations, were anal-

ysed to differentiate between fundamental objectives

and means objectives. If the assigned quotation ex-

pressed an essential objective, it became a candidate

for a fundamental objective. If the assigned quotation

expressed something that was important because of its

implications for some other objective, it was a candi-

date for a means objective. Finally, the transcriptions

were read through again to validate the structure of

the objectives.

5 THE IDENTIFIED OBJECTIVES

The fundamental objectives regarding an open and

adaptable environment were improving communica-

tion, increasing efficiency, enabling functionality, tak-

ing special needs into account, ensuring privacy, and

strengthening the community. These are further dis-

cussed one by one. System level means were de-

fined as those features of the system that could pos-

sibly contribute to an associated fundamental objec-

tive. Organisational level means represent the social

actions that contribute towards the fundamental ob-

jective.

5.1 Improve Communication

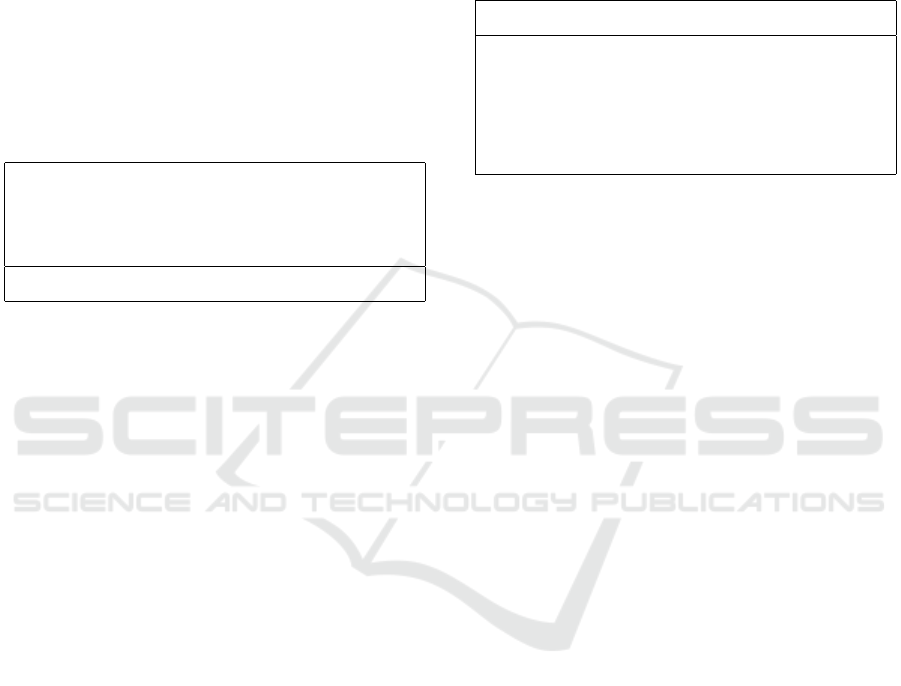

Table 3: Improve communication.

Communication culture

Discuss conflicting reservations

Access with mobile devices

Automatic conflict handling

Information about reserved spaces

Purpose for reservations

Information about the owner of a reservation

The first fundamental objective was improved com-

munication. The hope was that teachers, staff, and

students would not be isolated in the classrooms and

this would encourage more communication between

people. We thus interpreted communication as a cen-

tral objective, even though it often appeared implic-

itly in the data, because it is strongly connected to

other objectives. For example, the connection with

privacy appears as a need to have spaces available for

private conversations between teachers, students, and

other stakeholders. Participants emphasised that, re-

gardless of the features or possibilities of the system,

there is a need for a culture of open communication. It

is unavoidable that conflicts will occur when adjust-

ing to a new environment. Participants agreed that

the responsibility for solving conflicts cannot be out-

sourced entirely to technology. Even when a mech-

anism for automatically resolving reservation-related

conflict would exist, the prioritisations policy must be

determined by the people.

Communication can be improved in many ways

at the system level. The primary feature required

was that the system could be accessed by mobile de-

vices. The participants stressed that they do not have

time to look for a desktop computer during the day.

Identifying Objectives for a Learning Space Management System with Value-focused Thinking

29

One proposition was that there could be tablet devices

ported near the learning spaces, making it easy to

check the status of the space and make a reservation.

The participants brought up the issue that information

related to reservations needed to be easily accessed

and needed to contain some mandatory fields: contact

information of the person who made the reservation

and the purpose of the reservation. From a pedagogi-

cal perspective, there should also be features allowing

for commenting, rating and sharing knowledge about

the learning possibilities of spaces.

5.2 Strengthen Community

Table 4: Strengthen community.

Responsible use of shared resources

Negotiated rules and norms

Open discussion

A “right of way” feature Reservation status

Strong community was conceptualised as a situation

wherein the whole school community, among stake-

holders, is able to negotiate shared goals and work

together towards them. As discussed before, the par-

ticipants emphasised the need for a culture of open

communication. The participants concluded that they

needed to learn ways to co-operate in an open and

adaptable environment: the actions are less confined

to classrooms, and possible conflicting encounters

need to be negotiated. It is not just the policies and

rules that need to be negotiated with the school staff,

the whole operational culture of the school needs

shifting.

The participants proposed an interesting feature

for the system, which was named ’right of way’. The

idea was that the system could understand if some-

one had privileges to certain spaces and automati-

cally reorganise the reservations based on these priv-

ileges. This raised an intense discussion about what

constituted privileges and whether this idea conflicted

with the open and adaptable environment. Moreover,

this feature would be rather complicated to implement

technically.

An essential method of strengthening the commu-

nity was found to be the possibility of marking reser-

vations with open or closed status. An open reserva-

tion means that the space is reserved for certain peo-

ple, but others are still welcome to use it at the same

time. Some spaces are divided into smaller rooms

or areas, which could be used in parallel. For ex-

ample, two classes of deaf children, communicating

via sign language, could share the same room as long

as they would use the separating curtains available in

the room. This feature was appreciated by the partic-

ipants because it further supported the idea of collab-

oration and more efficient use of facilities.

5.3 Increase efficiency

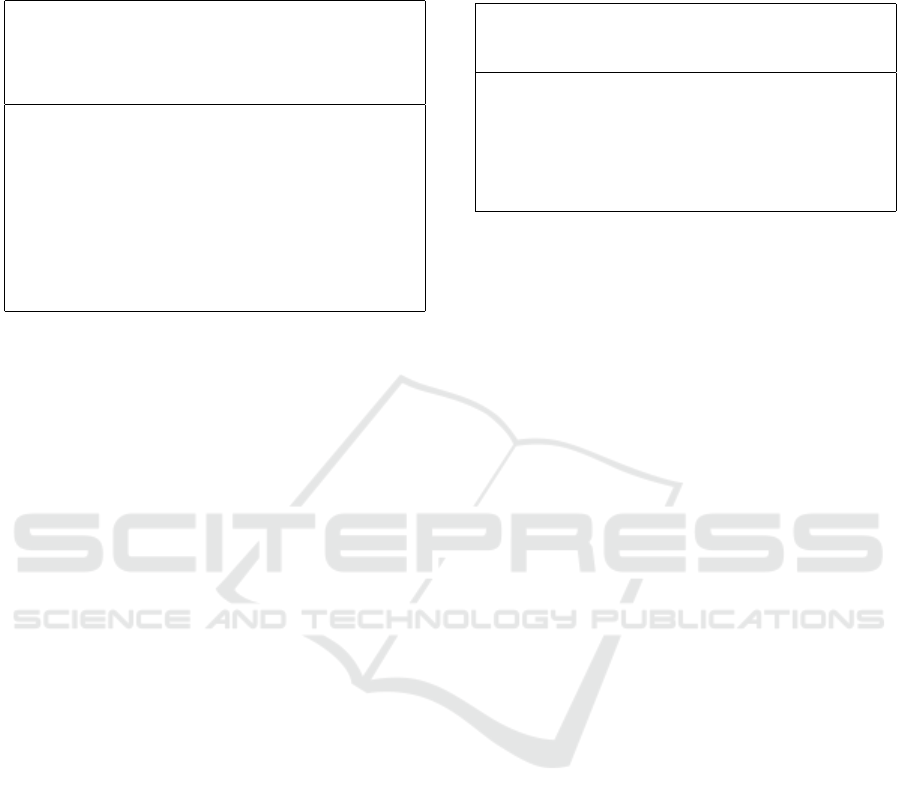

Table 5: Increase efficiency.

Planned behaviour

Visual information

Real-time information

High usability

Mobile use

The participants extensively discussed how everyday

life would be organised in the new environment. The

idea of not having their own classrooms was both fas-

cinating and frightening. The main expectation from

the technological tool was that it would help to organ-

ise the school activities. This is a crucial issue and af-

fects the whole work community, as one teacher com-

mented: ’I think, it [the system] would help to sort

things out, without unnecessary hassle. It is some-

thing that would have a great impact on our work at-

mosphere’. We interpret that time is the most lim-

ited resource the participants have, and it is extremely

important that using the developed technology does

not waste it. The participants also emphasised how

the ability to plan activities beforehand will make the

working day more tranquil.

When considering the actual system, the partici-

pants described that efficiency was about getting real-

time information that could be used everywhere and

that was easy to use. They also noted the possibil-

ity of having visual information. A concrete example

of the relationship between ease of use and efficiency

being discussed was based on their previous experi-

ences with a facility management system which had

a complicated function for removing reservations and

resulted in too many ‘no-show’ reservations. A visual

view (visual interface) of the building was important

for the participants. They were used to perceiving the

dimensions of the new building on the map. The pos-

sibility of making reservations with a visual picture

was thought to be more accessible than, for example,

a list of available spaces. Mobile access was again

mentioned, because it supported the idea of an open

and adaptable environment, by encouraging people to

move around.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

30

5.4 Enable Functionality

Table 6: Enable functionality.

Think differently

Functional pedagogy

Creative use of new learning spaces

Recommends suitable spaces

Shows accessories

Shows the purpose of space

Shows size of the space

Accessible from different locations

Accessible with different devices

The participants shared the view that action-based

learning has a very important role in special educa-

tion; therefore, enabling functionality is one of the

main goals of the open and adaptive environment, and

so, it seems rather self-evident for a functional ob-

jective. Functionality was conceptualised as a vision

where activities are always happening in the space

that is most suitable for the intended pedagogical

practice and that is available at the current moment.

The participants hoped that a more functional envi-

ronment would lead to more creative pedagogy be-

cause of the possibilities the new learning spaces are

offering. However, creativity was seen as a challenge:

how to question the old practices (and think differ-

ently) and pedagogically combine the needs of the

students and new learning spaces?

The main question at a system level was what

spaces are made available for reservation. There

seemed to be contradictory views between the new

way of understanding all spaces as ’open learning

spaces’ and the need for individual and private spaces

for certain tasks. This discussion resulted in interest-

ing observations, for instance: if there is a room with

several workstations, does the reservation apply to the

whole room or is it possible to reserve only a single

workstation? Solving these issues leads to a clearer

understanding of the level on which the decisions are

made: between people, pre-programmed in techno-

logical systems, or as institutional policies. Accord-

ing to the participants, the following features of the

system would enable functionality: the system is able

to recommend the most suitable spaces based on cer-

tain criteria, it is easy to see important information in

the system, and the system can be accessed from any

location in the school with most used devices.

5.5 Pedagogical Use

Table 7: Pedagogical use.

Empower students

Guide to responsible use of ICT

Proper authentication policy

Generic student accounts

Take account of special needs

Accessible user interface

The students of the school have a wide range of spe-

cial needs. Different perceptional abilities present a

challenge between the creative and dynamic use of

learning spaces and the need for structure and for-

mality. For example, it is essential for blind stu-

dents to learn how to navigate through the building

and find the necessary accessories inside the learn-

ing spaces on their own. The school introduced sev-

eral guides for this, including typical tracks for blind

people, but also innovative uniquely textured walls,

which helped identify the respective spaces, as well as

a novel sound-based guidance system (specific inter-

sections emitting different little tunes, to be uniquely

identifiable).

The participants, however, discussed that the

world itself is not structured for the needs of blind

people, and an important aim is to teach students to

act independently outside the school. This reflects the

idea that using the system should be one way to fa-

cilitate the students’ independence. The system was

seen as an opportunity to enhance responsibility by

empowering students to reserve learning spaces for

themselves and by guiding students towards respon-

sible use of information and communication technol-

ogy (ICT). The participants noted that permitting stu-

dents to use the system could result in accidental or

intentional misuse, but they seemed to agree that, de-

spite the possible unwanted scenarios, it is important

to accustom students to ICT.

An important issue was to deciding on user poli-

cies and authentication within the system. One pos-

sibility was to create user accounts for every student,

but this would raise challenges related to security and

technical implementation. Information related to stu-

dents has high-security classification, which would

mean tight restrictions in the system. The partici-

pants proposed the possibility of making generic user

accounts for students, so their personal information

could not be revealed. Special needs should be taken

into account in system development to make pedagog-

ical use of the system possible.

Identifying Objectives for a Learning Space Management System with Value-focused Thinking

31

5.6 Ensure Privacy and Security

Table 8: Ensure privacy and security.

Respect private spaces

Critical information in dedicated server

An important matter of discussion was how privacy

could be ensured in the open and adaptable environ-

ment. The participants emphasised the need for pri-

vate spaces to have conversations with stakeholders

and how this privacy needs to be respected. They also

commented that visual positioning information about

staff or students could be very useful, but that it raises

many privacy-related problems. However, partici-

pants explained that they have actually had emergency

situations during which a student has been completely

lost.

From a technical perspective, the discussion fo-

cused around how the current technological infras-

tructure is connected to the system and what security

vulnerabilities it might cause. The participants con-

cluded that critical student information is stored in

dedicated servers and that access to the system should

be restricted.

6 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

This paper briefly presents the process and the results

of our requirements analysis for a rather typical in-

formation management system, but for a completely

new environment, represented by the open and adapt-

able school. It was clear from the beginning that

we needed to re-imagine the characteristics of facil-

ity management systems as they seemed to be devel-

oped primarily for administrative purposes. In prac-

tice, we needed to encourage the participants reflect

on the new surroundings and their everyday work to

frame what was important to them and to clarify what

they wanted to achieve. To reach this goal, we organ-

ised four workshops, during which we applied value-

focused thinking to identify objectives for developing

a learning space management system for an open and

adaptable environment. Our analysis had two stages:

first, we needed to analyse the workshops from the

perspective of requirements specification in order to

establish necessary attributes of the system, that is,

functions, a use case diagram, and use case scenarios.

After the workshops, we made a more in-depth in-

vestigation of the data using an open coding analysis.

This two-staged analysis was used to verify our anal-

ysis. As Morse et al. (2002) have presented, data may

demand to be treated in different ways, so the analytic

procedure should match the research questions. The

first analysis stage was more practical and straightfor-

ward while the second stage required more reflective

strategy and critical discussions about the project be-

tween the authors of this paper.

The identified fundamental objectives regarding

the open and adaptable environment included follow-

ing: improving communication, strengthening com-

munity, increasing efficiency, enabling functionality,

pedagogical use of the system, and ensuring privacy

and security. These fundamental objectives, as well

as the means to achieve them, are described from the

system and organisational level. We argue that this

will help other researchers and implementers to take

a more holistic view in the development phase: the

functions and features of the system need to be con-

sidered together with organisational level means, and

they should be in line with approved fundamental ob-

jectives. The results give more in-depth representa-

tion about the context, people, and environment for

which the system is developed.

We implemented the principles of participatory

design in our project. The participants had a real op-

portunity to influence what kind of system will be de-

veloped, and there was strong collaboration between

researchers and participants. Researchers were able

to learn about the work and the new environment of

the participants and the researchers were able to share

knowledge about technical possibilities as well as re-

strictions. We also collided with issues when consid-

ering our project as participatory design. VFT does

not put emphasis on the complex power relationships

participants may have. The method assumes that peo-

ple are able to communicate their thoughts, regard-

less of the social hierarchies that may constrain the

discussion. Furthermore, VFT examines the identi-

fied objectives as a whole, while the objectives be-

tween different stakeholders might be very conflict-

ing. The question is, whose objectives are we sup-

posed to meet? Claiming that the project is based

purely on ‘participatory design’ may even be consid-

ered somewhat unjustified, due to the fact that the ac-

tual analysis (objective identification) was made by

the researchers. Even when we were concentrating

on the objectives of participants, the role of the par-

ticipants was more that of informants than actors.

The philosophy behind VFT is that the identified

objectives are based on the values of decision mak-

ers rather than just comparing possible alternatives.

The concept of value is very challenging, because

of the different definitions of value in different re-

search fields and even among individuals. Keeney’s

(1992; 1996) definition is very general, and the dif-

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

32

ference between the concepts of value and objective

is not completely clarified. To underline the point,

for some people, value is about currency or efficiency

and for others it is about ethical questions. As an

anecdote, Cockton (2004; 2006) changed the name

of the concept from value to worth after struggling

with the same issue. It may seem appealing to use a

pre-defined set of values, as in Schwartz’s (2012) the-

ory of basic values, which provides more depth to the

contents and structure of values, but as Isomursu et

al. (2011) discussed, using a pre-defined framework

to analyse and interpret the findings can lead to con-

firmation bias.

Even if we embrace Keeney’s definition, the ques-

tion arises of how to reach abstract constructions that

may be difficult to form as statements. For exam-

ple, Iversen et al. (2012) pointed out that values are

not static entities that are waiting for researchers and

developers to collect them, but more like changing,

complex and abstract ways of being and thinking.

Keeney seems to take it for granted that decision mak-

ers are automatically people who are able to express

what is important to them. For example, when de-

signing with children, there should be more appropri-

ate methods than just asking ’what it is that one cares

for’. People’s values tend to emerge, change, and con-

flict, and researchers should carefully consider who is

answering these questions and what they mean.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our gratitude for the Val-

teri School Onerva’s personnel for participating in

the research project. We also thank Kirsi Heinonen,

M.Sc., for assisting in data collection. This research is

funded by the Valteri School Onerva and the Univer-

sity of Jyvaskyla, Faculty of Information Technology

under the project entitled ONSPACE. The research

did not receive any specific grant from funding agen-

cies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sec-

tors.

REFERENCES

Abelein, U. and Paech, B. (2015). Understanding the influ-

ence of user participation and involvement on system

success – a systematic mapping study. Empirical Soft-

ware Engineering, 20(1):28–81.

Alessandrini, A., Cappelletti, A., and Zancanaro, M.

(2014). Audio-augmented paper for therapy and ed-

ucational intervention for children with autistic spec-

trum disorder. International Journal of Human-

Computer Studies, 72(4):422–430.

Barki, H. and Hartwick, J. (1994). Measuring user partici-

pation, user involvement, and user attitude. MIS Quar-

terly, 18(1):59–82.

Benton, L., Vasalou, A., Khaled, R., Johnson, H., and

Gooch, D. (2014). Diversity for design. In Proceed-

ings of the 32nd Annual ACM Conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’14, pages 3747–

3756, New York, New York, USA. ACM Press.

Bergvall-K

˚

areborn, B. and St

˚

ahlbrost, A. (2008). Participa-

tory design: one step back or two steps forward? In

Proceedings of the Tenth Anniversary Conference on

Participatory Design 2008, pages 102–111.

Bjerknes, G. and Bratteteig, T. (1995). User participation

and democracy: a discussion of Scandinavian research

on system development. Scandinavian Journal of In-

formation Systems, 7(1):73–98.

Cockton, G. (2004). Value-centred HCI. In Proceedings of

the Third Nordic Conference on Human-Computer In-

teraction - NordiCHI ’04, pages 149–160, New York,

New York, USA. ACM Press.

Cockton, G. (2006). Designing worth is worth design-

ing. In Proceedings of the 4th Nordic Conference

on Human-Computer Interaction Changing Roles -

NordiCHI ’06, number October, pages 165–174, New

York, New York, USA. ACM Press.

Corbin, J. M. and Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory

research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria.

Qualitative Sociology, 13(1):3–21.

Ehn, P. (1988). Work-Oriented Design of Computer Arti-

facts. PhD thesis, Ume

˚

a Universitat.

Frauenberger, C., Good, J., Fitzpatrick, G., and Iversen,

O. S. (2015). In pursuit of rigour and accountabil-

ity in participatory design. International Journal of

Human-Computer Studies, 74:93–106.

Frauenberger, C., Good, J., and Keay-Bright, W. (2011).

Designing technology for children with special needs:

bridging perspectives through participatory design.

CoDesign, 7(1):1–28.

Friedman, B. (1996). Value-sensitive design. Interactions,

3(6):16–23.

Guha, M. L., Druin, A., and Fails, J. A. (2008). Designing

with and for children with special needs. In Proceed-

ings of the 7th International Conference on Interac-

tion Design and Children - IDC ’08, page 61, New

York, New York, USA. ACM Press.

Halskov, K. and Hansen, N. B. (2015). The di-

versity of participatory design research practice at

PDC 2002–2012. International Journal of Human-

Computer Studies, 74:81–92.

Harris, M. A. and Weistroffer, H. R. (2009). A new look at

the relationship between user involvement in systems

development and system success. Communication of

the Association for Information Systems, 24(1):Article

42.

He, J. and King, W. R. (2008). The role of user partici-

pation in information systems development: implica-

tions from a meta-analysis. Journal of Management

Information Systems, 25(1):301–331.

Iivari, J., Isom

¨

aki, H., and Pekkola, S. (2010). The user -

the great unknown of systems development: reasons,

Identifying Objectives for a Learning Space Management System with Value-focused Thinking

33

forms, challenges, experiences and intellectual con-

tributions of user involvement. Information Systems

Journal, 20(2):109–117.

Isomursu, M., Ervasti, M., Kinnula, M., and Isomursu, P.

(2011). Understanding human values in adopting new

technology - a case study and methodological discus-

sion. International Journal of Human-Computer Stud-

ies, 69(4):183–200.

Iversen, O. S., Halskov, K., and Leong, T. W. (2012).

Values-led participatory design. CoDesign, 8(2-

3):87–103.

Keeney, R. L. (1992). Value-focused thinking: a path to

creative decisionmaking. Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Keeney, R. L. (1996). Value-focused thinking: identifying

decision opportunities and creating alternatives. Eu-

ropean Journal of Operational Research, 92(3):537–

549.

Keeney, R. L. (2013). Identifying, prioritizing, and using

multiple objectives. EURO Journal on Decision Pro-

cesses, 1(1-2):45–67.

Kujala, S. (2003). User involvement: a review of the ben-

efits and challenges. Behaviour & Information Tech-

nology, 22(1):1–16.

Mahmood, A. M., Burn, J., Gemoets, L., and Jacquez, C.

(2000). Variables affecting information technology

end-user satisfaction: a meta-analysis of the empirical

literature. International Journal of Human-Computer

Studies, 52(4):751–771.

Malinverni, L., MoraGuiard, J., Padillo, V., Mairena, M.-

a., Herv

´

as, A., and Pares, N. (2014). Participatory

design strategies to enhance the creative contribution

of children with special needs. In Proceedings of the

2014 Conference on Interaction Design and Children

- IDC ’14, pages 85–94, New York, New York, USA.

ACM Press.

McGill, T. and Klobas, J. (2008). User developed applica-

tion success: sources and effects of involvement. Be-

haviour & Information Technology, 27(5):407–422.

Morse, J. M., Barrett, M., Mayan, M., Olson, K., and

Spiers, J. (2002). Verification strategies for establish-

ing reliability and validity in qualitative research. In-

ternational Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2):13–

22.

Muller, M. J. and Kuhn, S. (1993). Participatory design.

Communications of the ACM, 36(6):24–28.

¨

Ozen, A. and Ergenekon, Y. (2011). Activity-based inter-

vention practices in special education. Educational

Sciences: Theory and Practice, 11(1):359–362.

Pacheco, C. and Garcia, I. (2012). A systematic litera-

ture review of stakeholder identification methods in

requirements elicitation. Journal of Systems and Soft-

ware, 85(9):2171–2181.

Parnell, G. S., Hughes, D. W., Burk, R. C., Driscoll, P. J.,

Kucik, P. D., Morales, B. L., and Nunn, L. R. (2013).

Invited review-survey of value-focused thinking: ap-

plications, research developments and areas for future

research. Journal of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis,

20(1-2):49–60.

Sanders, E. B.-N., Brandt, E., and Binder, T. (2010). A

framework for organizing the tools and techniques of

participatory design. In Proceedings of the 11th Bien-

nial Participatory Design Conference, PDC ’10, page

195, New York, New York, USA. ACM Press.

Sanoff, H. (2007). Special issue on participatory design.

Design Studies, 28(3):213–215.

Sanoff, H. and Walden, R. (2012). School environments. In

The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conser-

vation Psychology, pages 276–294.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and struc-

ture of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests

in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psy-

chology, 25(C):1–65.

Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the schwartz theory

of basic values. Online Readings in Psychology and

Culture, 2:1–20.

Sheng, H., Nah, F., and Siau, K. (2005). Strategic implica-

tions of mobile technology: a case study using value-

focused thinking. The Journal of Strategic Informa-

tion Systems.

Sheng, H., Siau, K., and Nah, F. F.-H. (2010). Under-

standing the values of mobile technology in education.

ACM SIGMIS Database, 41(2):25.

Spinuzzi, C. (2005). The methodology of participatory de-

sign. Technical Communication, 52(2):163–174.

Williams, R. M. (1979). Change and stability in values

and value systems: A sociological perspective. Un-

derstanding Human Values: Individual and Societal

Values, 1:5–46.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

34