Perceptions of Digital Footprints and the Value of Privacy

Luisa Vervier, Eva-Maria Zeissig, Chantal Lidynia and Martina Ziefle

Human-Computer Interaction Center, RWTH Aachen University, Campus Boulevard 57, Aachen, Germany

Keywords: Information Privacy, Privacy Paradox, Privacy Calculus, Privacy Awareness, Information Sensitivity.

Abstract: Nowadays, life takes place in the digital world more than ever. Especially in this age of digitalization and Big

Data, more and more actions of daily life are performed online. People use diverse online applications for

shopping, bank transactions, social networks, sports, etc. Common to all, regardless of purpose, is the fact

that personal information is disclosed and creates so-called digital footprints of users. In this paper, the

questions are considered in how far people are aware of their personal information they leave behind and to

what extent they have a concept of the attributed importance of particularly sensitive data. Moreover, it is

investigated in how far people are concerned about their information privacy and for what kind of benefit

people decide to disclose information. Aspects were collected in a two-step empirical approach with two focus

groups and an online survey. The results of the qualitative part reveal that young people are not consciously

aware of their digital footprints. Regarding a classification of data based on its sensitivity, diverse concepts

exist and emphasize the context-specific and individual consideration of the topic. Results of the quantitative

part reveal that people are concerned about their online privacy and that the benefit of belonging to a group

outweighs the risk of disclosing sensitive data.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, a huge portion of everyone’s life takes

place in the digital world. It exceedingly permeates

into our everyday life as more and more formerly

offline tasks can now be performed online – e.g.,

shopping, bank transactions, communication. For

many adolescent and younger adults – the generation

of the Digital Natives (Helsper, 2010) – the fact that

these tasks used to be carried out exclusively offline

is not even imaginable anymore. This digital

development and era of big data accelerates the

market, facilitates to stay socially connected, and

offers many more advantages. Every day, new

applications are developed and improved and reach

more and more formerly offline areas of life – e.g.

health care, driving, fitness. Using those online

possibilities does have another side to it, however. It

goes hand in hand with the sharing of data and

disclosure of private information since all

applications collect and aggregate data about their

users. As the Internet of Things grows in importance

and ubiquity and formerly private areas of life get

“online”, keywords such as “information privacy

concern” or “risks of disclosure” are common issues

to be discussed in the public. Science did not fall short

in noticing and many studies in the last decade report

that most Internet users are quite concerned about

their information privacy and the risks of disclosing

information (e.g., Bansal et al., 2010; Rainie et al.,

2013; Data Protection Eurobarometer, 2015;

TRUSTe, 2014). Paradoxically, digital user behavior

does not necessarily reflect this attitude, a

phenomenon commonly referred to as the “Privacy

Paradox” (Norberg et al., 2007). The theory of the

Privacy Calculus (Krasnova and Veltri, 2010) seeks

to explain this discrepancy between attitude and

behavior. It hypothesizes that users evaluate and

weigh the risks and benefits for a decision about

whether to use an application or disclose information

(e.g. Dinev and Hard, 2006). Ideally, users are aware

of all the risks and benefits and therefore able to

evaluate them rationally. In reality, though, a decision

whether to disclose or share information is made in

limited time, with sometimes limited knowledge of

the consequences, and affectively (e.g. Acquisti et al.

,2015; Kehr et al., 2015). Empirical studies show that

people are concerned, they rate risks high, and know

much about data collection malpractices – the latter,

however, they only voice when explicitly asked about

it (Data Protection Eurobarometer, 2015). But do

they consider these aspects every time they make a

80

Vervier, L., Zeissig, E-M., Lidynia, C. and Ziefle, M.

Perceptions of Digital Footprints and the Value of Privacy.

DOI: 10.5220/0006301000800091

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security (IoTBDS 2017), pages 80-91

ISBN: 978-989-758-245-5

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

decision about data disclosure?

In the first part of this study, we took a step back and

empirically assessed how aware young adults are

about data collection and privacy issues – awareness

in this context meaning to take these issues

intentionally into consideration without them being

pointed out explicitly. Understanding individual

behaviors, two focus groups were carried out, guided

by the questions a) where digital footprints are left, b)

what data types are disclosed when using the Internet,

and c) how data is categorized into more or less

sensitive data. Complementing this exploratory

approach, an online survey of German Internet users

was conducted, in a second step. This aims to contrast

the “implicit” method (focus group) with “explicitly”

asking about the importance of privacy (online

questionnaire), the prevalent concerns, and the actual

privacy protection behavior. Additionally, reasons

within the privacy calculus are assessed.

1.1 Information Privacy

Privacy is a multifaceted construct that has been

defined by researchers of different areas and

intentions. Definitions range from the “right to be left

alone” (Warren and Brandeis, 1890), a “state of

limited access or isolation” (Schoeman, 1984) and the

“control” of access to the self and of information

disclosure (Altman, 1975; Westin, 1976). The

digitalized world and Bid Data put into focus one

subset of privacy: the concept of information privacy

("the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to

determine for themselves when, how, and to what

extent information about them is communicated to

others”, Westin, 1967). Not only is the concept and

its definition rather vague. Also, its measurement is

proving to be difficult. Often, the concern for

information privacy construct is used to get an idea of

what privacy means to individuals (Kokolakis, 2015).

To understand privacy attitudes the actual behavior

regarding privacy and data disclosure should to be

taken into account as well (e.g. Acquisti et al., 2015;

Keith et al., 2013; Ziefle et al., 2016).

1.2 Privacy Paradox

Several studies report a high level of information

privacy concern of Internet users – but the actual

behavior regarding privacy protection and data

disclosure deviates (e.g. Norberg et al., 2007;

Carrrascal et al., 2013; Taddicken, 2014). This

discrepancy between attitude and exhibited actual

behavior is known as the privacy paradox. Studies

have shown that, in general, people voice concern for

their data, want to protect it, and want control over

who has access (Bansal et al., 2010; Acquisti and

Grosklags, 2005). Nevertheless, people disclose a

multitude of personal information, sometimes even

without any restrictions concerning the recipients or

erroneous conceptions of their privacy settings (e.g.,

Lewis et al., 2008; Chakraborty et al., 2013; Van den

Broeck et al., 2015). How does that come about? One

possible explanation is the so-called privacy calculus.

1.3 Privacy Calculus

The Privacy Calculus Theory assumes that people

decide whether to disclose information or use an

application based on several factors, in a given

situation. If the perceived benefits outweigh the

perceived risks, information is more likely to be

disclosed; whereas if perceived risks outweigh the

possible benefits, disclosure is less likely to happen

(e.g., Li et al., 2010; Dinev and Hart, 2006). Hui et al.

(2006) have identified seven possible benefits for

information disclosure: monetary savings, time

savings, self-enhancement, social adjustment,

pleasure, novelty, and altruism. These factors are

oftentimes dependent on a single situation and the

decision is made more in the spur of the moment than

with a lot reasoning (cf. Acquisti et al., 2015; Kehr et

al., 2015). Choices are often made by valuating

instant gratification more than possible of longtime

risks or ramifications (ibid). Optimism bias, the

tendency to believe that the risks for oneself is less

compared to others (Cho et al., 2010), and affective

states influence risk assessment (Kehr et al., 2013).

Privacy decisions are made in a state of incomplete

information and bounded rationality (Acquisti and

Grossklags, 2005). Users lack the ability and

necessary information to rationally and completely

evaluate privacy risk and disclosure benefits

(Kokolakis, 2015). Studies show, that risks are

evaluated high if asked about them (e.g., Bansal et al.,

2010; Rainie et al., 2013; Taddicken, 2013; European

Commission, 2011; Protection Eurobarometer, 2015;

TRUSTe, 2014). Young people do adjust their

privacy settings in online social networks (Boyd and

Hargittai, 2010), a field that has been thoroughly

discussed in media. Other areas of Internet usage have

not been covered that much in media and society. Are

risks even considered in those short moments, for

example when deciding to install a new smartphone

application? Is it not rather that risks are ignored or

are unconscious in most situations? Do users even

consider all their knowledge about risks, how much

or little it may be? Based on the limited time span in

the actual usage situation most users take to make

Perceptions of Digital Footprints and the Value of Privacy

81

decisions, it can be hypothesized that only the most

obvious risks are considered, if at all.

1.4 Privacy Awareness

The concept of privacy awareness has been studied

as an antecedent to privacy concerns (e.g.: Smith,

Dinev and Xu, 2011; Xu et al., 2008; Brecht et al.,

2011). It is defined as the “extent to which an

individual is informed about organizational privacy

practices and policies” (Xu et al., 2008). The scales

used to measure privacy awareness obtain users’

knowledge that privacy issues exist and media

coverage of the topic (e.g. “I am aware of privacy

issues and practices in our society”, Xu et al., 2008,

Xu et al., 2011). These measures cannot obtain

whether this knowledge is taken into consideration

when making privacy decision. The term awareness

is also used in this paper, but meant is a more implicit

awareness or consciousness: are users considering

their knowledge about privacy risks without them

being emphasized – e.g. by the context of a privacy

survey or experiment?

1.5 Information Sensitivity

Not all types of information are equally sensitive and

they do not bring about the same risks. Mothersbaugh

et al. (2012) define sensitivity of information as “the

potential loss associated with the disclosure of that

information”. When users weigh privacy risks and

benefits of disclosure to make a privacy decision, they

have to consider the types of information they know

will be affected. Thus, if risks are aware in users’

reasoning about privacy decisions, risks should be

considered when evaluation the sensitivity of data

types.

2 QUESTIONS ADDRESSED AND

LOGIC OF EMPIRICAL

PROCEDURE

In this paper, individual awareness of data footprints

in the Internet, type of data, and conceptions of

different sensitivity categories of data are explored

qualitatively. Furthermore, attitudes towards privacy

concerns in the context of internet usage, security

behavior, as well as the privacy calculus are explored

quantitatively.

Two focus groups aimed at exploring the

awareness of data collection and privacy risks without

asking about them directly. Furthermore, they were

meant to reveal if a mental concept of privacy issues

with online services existed in the young and

technology-adept Internet users. Since the methodical

approach of the focus group intended to collect

different opinions of people´s points of view, very

general questions were guiding the group discussion:

(1) Where do you leave so called “data tracks”? (2)

What kind of data do you leave in the Internet when

using it? and (3) Are there different types of data

which have a stronger meaning to you than other

data?

The second, quantitative study focused, firstly, on

privacy attitudes and protection behavior and,

secondly, on reasoning within the privacy calculus

model. Questions guiding the research were (1) In

how far do people care about privacy dealing with

internet usage in general? (2) Do age or gender have

an impact on data protection behavior? and (3) Do age

or gender have an impact on the privacy calculus?

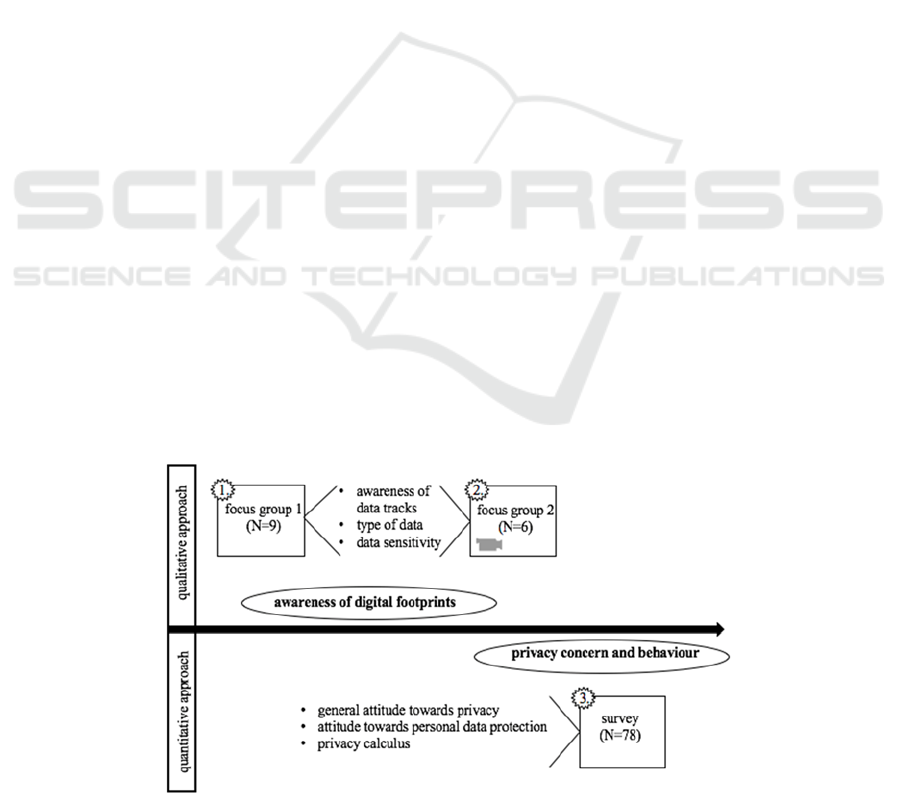

In Figure 1, an overview of the study process is

depicted.

Figure 1: Overview of research process.

IoTBDS 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

82

3 UNDERSTANDING PRIVACY

AWARENESS: THE FOCUS

GROUP APPROACH

The aim of the focus group approach was to identify

and discuss young adults’ ideas of individual digital

footprints left in the digital world when using devices

and applications connected with the Internet,

association of data types, and distinction of data types

due to their personal perceived sensitivity. To this

end, two consecutive focus groups were run.

3.1 Methods

Participants were introduced to the motto of the focus

group: “self-confident in the digital world.” In the

introductory part, participants were encouraged to

talk about all kinds of digital applications they use in

daily life and what kind of data they disclose in this

context. A general question (“Where do you leave so

called data tracks?”) was raised in the beginning.

As a stimulator for the discussion, pictures were

shown to the first group, and videos to the second one.

The pictures featured familiar providers and brands;

the videos described smart phone apps that collect

sensitive data. This stimulation was indented to

reveal, whether more digital footprints are “known”

when hints are shown. Therefore, they were given at

a point where the participants did not come up with

more data tracks on their own. The different data

types mentioned were written on paper and collected

on a pin board.

In a next step, participants were asked to

individually arrange data types into categories of how

sensitive they perceive them to be.

In the end, a short questionnaire was applied. Its

items were taken from literature (e.g. Morton, 2013)

and discussions with experts in the field and had to be

answered on 5-point Likert scales.

Familiarity with the topic: “How much have you

dealt with the topic privacy so far?” (1= “it´s the first

time I have heard about it” to 5=”I am very familiar

with this topic”).

Privacy and data protection: “How important is

privacy to you?”, “How important is it for you to

protect your information privacy?”, and “How

intensively do you protect your data?” (1=“very

unimportant” to 5=“very important.”)

Desire for privacy: “I'm comfortable telling other

people, including strangers, personal information

about myself.”, “I am comfortable sharing

information about myself with other people unless

they give me a reason not to.“, “I have nothing to

hide, so I am comfortable with people knowing

personal information about me. (1=“I do not agree at

all” to 5= “I totally agree”).

Last but not least, attitudes to the statement “The

digital world is for me…” were assessed with a

semantic differential (Heise, 1970) where 19 bipolar

word-pairs had to be evaluated in the context of using

digital media, e.g. “important-unimportant,”

“interesting - uninteresting,” innovative -

uninspired”. The full list of word-pairs can be taken

from figure 6.

3.2 Participants

The focus groups were conducted with 14 participants

in total but split into two sessions. The sample was

composed of eight female and six male students with

an age range from 19 to 29 years (M=23.2, SD=3.3).

The courses of studies covered a broad range

(technical communication, political science,

teaching, architecture, biology, and health

economics).

3.3 Results

Data of the qualitative focus group studies regarding

awareness of personal digital footprints and

sensitivity rankings were analyzed descriptively, with

qualitative data analysis by Mayring (2010).

General attitudes towards privacy

In general, participants reported to be familiar with

the topic privacy (M=4.1/ 5 points max, SD=0.6).

Asked about how important it is to protect their

general privacy, they also scored quite high (M=4.3;

SD=1.0). Questions concerning the importance of

protecting their information privacy was rather

important (M=3.7, SD=0.9) as well as the intensity of

protecting personal data with M=3.7 (SD=0.9). The

three items which measured a dispositional privacy

concern, like an individual level of need or desire for

privacy, were merged into one overall score. With a

mean of M=1.9 (SD=0.9), a general low desire for

privacy was noticed.

Awareness of Digital footprints

In the beginning, participants were encouraged to

brainstorm about all the applications they use

(“Where do you leave so called data tracks?”). The

intention behind this question was to point out the

participants’ digital footprints. First answers to the

questions contained those data types that people often

must actively provide when registering or signing in

to Web Services, as well as obvious data that is

collected within social media. Especially in the first

Perceptions of Digital Footprints and the Value of Privacy

83

focus group of very young students, the

brainstorming often came to a halt because the

participants needed time and inquiries to come up

with more applications and data types. Data types that

are more “covertly” collected, such as location data

or interests, were not as present in the beginning. The

stimulation media (pictures or videos) induced more

ideas, especially concerning applications of “the

Internet of Things,” where the data collection is less

obvious: cars collecting driving behavior and

location, activity trackers revealing everyday routines

and habits, etc. Participants seemed to know about

many data collection practices when pointed to them,

but they did only come up with a few of them on their

own and needed a long time. In the end, 45 fields were

mentioned, illustrated in the word cloud (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Reported providers where personal data is left

(N=45 mentions).

The mentioned fields compassed a wide range of

several providers. 12 categories were identified from

these: social media, location, messenger, entertain-

ment, booking, banking, connected systems, health,

service, free time and leisure activities, information,

and organization. In a next step, participants reported

which kind of data they leave when using the

mentioned Internet or app providers. The following

word cloud portrays the 42 mentioned data types

(Figure 3).

Figure 3: Reported data types (N=42 mentions).

16 categories arose out of the mentioned data types

such as personal data, profession, finances, biometric

data, state of health, medical information, fitness

behavior, political orientation, social contacts,

photos/videos, interests/hobbies, communication,

location, club membership, purchase behavior,

mobility behavior.

While summing up the data types a male participant

(26 years old) spoke out loud his thoughts and

realized:

”How seldom you actually think about this

where you indicate your data or when you

download apps and accept all

authorizations. You seldom wonder about

exactly this background.”

Delving deeper in the topic, participants began to

deal stronger with their own awareness of data they

leave behind:

“(..) once thinking about this topic you

realize that you still use it (applications)”

(male, 26 years old).

Doubts came up concerning the usage of different

apps, participants described that it has become an

integral part of people´s life and one can no longer do

without it. Also, social Incentives played a part:

“The social incentive is just too great,

especially with Facebook. If I would not be

member of some Facebook groups of

university, I would miss a lot of information

since E-mails are not sent anymore”

(female, 26 years old).

As well as habituation as reasons for using

different apps:

“You have once reached a point where

things are incredibly prevalent and you do

not have the possibility to withstand it

anymore” (female, 23 years old).

Sensitivity of data

Once all mentioned data fields and types were

collected, the question was posed if there are different

types of data which have a stronger meaning to the

participants than other data. Without naming the topic

privacy, it was intended to draw attention to it. The

tenor of the responses was comparable across

participants and could be summarized in one

comment, a male, 22 years old participant stated:

“Declare as little as possible online.”

In order to receive some more opinions, the question

was emphasized and it was inquired if there is

information which deserves more protection.

Participants reported that

“Everything that involves information about

a person such as name and address needs to

be protected” (male, 25 years).

IoTBDS 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

84

Another female participant stated that everything

must be protected that can be used against oneself.

Reversely, a male participant stated his opinion that:

”Depending on who receives data it

sometimes seems positive and negative in the

same way to me. Talking about fitness or

health it is positive for me if science can

conclude something out of my data. In this

case, I would agree to disclose my disease

data. However, if the same data goes to

insurance companies I would deny it.”

(male, 25 years).

The group drew the conclusion that the way of

protecting or disclosing data is strongly individual

and a contextual consideration, depending on the

characteristics of the receiver of data.

In the further course of the group discussion,

participants were encouraged to contemplate about

different sensitivity rankings. In the end, five

different ideas were created and presented by the

focus group participants. One participant suggested a

two-stage classification, distinguishing between data

which is okay to disclose and other data which seem

to be more sensitive and needs further restrictions

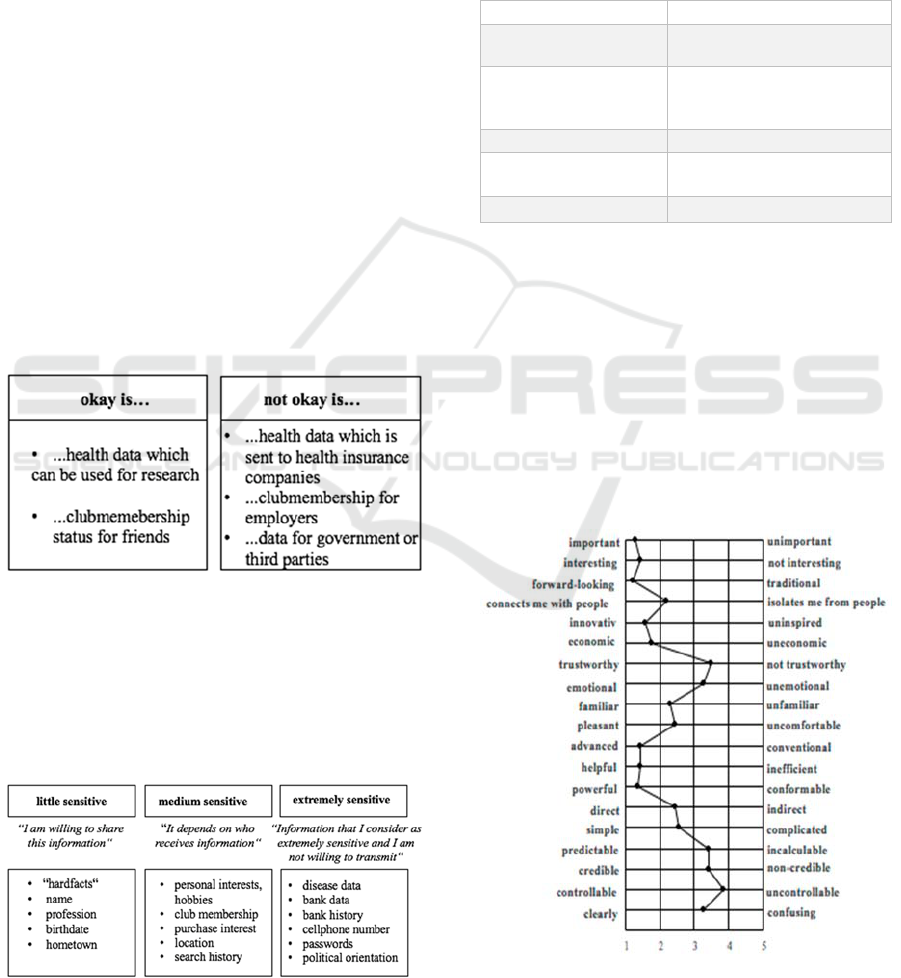

when sharing (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Two-step sensitivity ranking.

Moreover, two three-step classifications were

presented with data participants are willing to share,

data which depends on where it is retained, as well as

data which is considered as very much in need of

protecting. Exemplarily, one is shown for both ideas

since distinction (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Three-step sensitivity ranking.

A further classification was created with four steps by

a participant. The idea was almost like the three-step

version with the difference that the fourth step was

called “not relevant” and included the example “car

control”. As a last idea regarding the question in how

many sensitivity steps all the different data should be

divided, one participant came up with a 6-step

ranking (Table 1).

Table 1: 6-step sensitivity classification.

do not disclose at all

disease and health data

very sensitive

bank data, credit card data,

and moving profile

more critical

search history, purchase

history, photo analyses,

vacation time

critical

group of friends

okay

club membership

activities and interests

I do not care

name, address, profession

While contemplating the categorization, the

participants worked out some important factors that

significantly influence their openness to share

information: characteristics and type of the receiver

of the information, the purpose of information

collection, context of disclosure, and familiar

practices to what information is already or rather

usually known.

In the end, participants were asked to assess a

semantic differential which measured the connotative

meaning participants associate with the statement:

“For me, the digital world seems…”

Figure 6: Semantical differential (N=14 participants).

Perceptions of Digital Footprints and the Value of Privacy

85

Generally, the perceived digital world was

positively connoted, with positive associations such

as it is important, interesting, and helpful. However,

distrust and concern were also shown by negative

associations such as not trustworthy, unemotional,

incalculable, non-credible, uncontrollable, and

confusing, among others (Figure 6).

4 MEASURING ATTITUDES IN

THE PRIVACY CONTEXT: THE

QUESTIONNAIRE APPROACH

In a quantitative approach, general attitudes towards

Internet privacy, behavior of personal data protection

was focused at as well as the phenomenon of the

privacy calculus. In contrast to the implicitly

questioning in the focus groups, the online survey

aimed at explicitly posed question regarding the

above-mentioned aspects. The aim was to quantify

how relevant privacy aspects are for participants in

general.

The questionnaire was sent out by email to a wider

audience of the university, including staff, but also

private contacts of the authors.

4.1 Methods

The questionnaire was sent out consisted of four

parts. First, demographic data (gender, age) was

assessed. Then it was surveyed to what an extent

participants have ever been concerned with the topic

information privacy and in how far participants have

dealt with the topic of data protection so far, using a

10-point scale (1=“it´s totally new to me” to 10=“I

am familiar with it”).

In a second part, general privacy attitude was

investigated with the item “Protecting my privacy is

very important to me”, using a 5-point Likert-scale

(1=“I do not agree at all” to 5=“I totally agree.”)

The third part surveyed data protection behavior

with three items that were taken from Buchanan

(2007): (1)“I am exerted to protect my privacy in the

Internet by e.g. erasing cookies, installing specific

software and/or changing settings.” (2) “I am trying

to actively protect my data in the Internet, by, e.g.,

erasing cookies, installing specific software and/or

changing settings.” (3) “I have once refrained from

the usage of an application, because I have seen my

privacy being at risk.” Again, a 5-point Likert scale

was used (1=“I do not agree at all” to 5=“I totally

agree.”).

The last part contained statements outlining

aspects of the privacy calculus (items were based on

findings in the focus groups study): (1)“I would

always disclose my data for applications many of my

friends /colleagues/relatives use, in order to not be

excluded.”(social pressure) (2) “Protecting my

privacy on the internet (even better) is too time-

consuming for me.” (effort) (3) “I would disclose

more data, if I received money for it”(reward).

4.2 Participants

The questionnaire was completed by 78 participants

(33 women and 45 men) in an age range between 28

and 66 years (M=31.9 years, SD=11.7). For an age

comparison regarding the different items, the sample

was split by median into two groups: 35 participants

fell into the “younger group” (< 28 years, 13 women

and 22 men) and 42 into the “middle-aged group”

aged (> 28 years, 20 women and 22 men). In general,

the sample was more familiar with the topic privacy

(M=7.3/10 points max, SD=2.1 than with the topic of

data protection (M=6.7, SD=2.4).

4.3 Results

The data from the questionnaire dealing with the

participants´ attitude towards privacy concern and

their actual behavior was analyzed with non-

parametric tests due to the small sample size (Mann-

Whitney-U-Test). In the analysis, we put a focus on

age and gender as potential influencing factor of

privacy and data protection attitudes.

Importance of privacy

In general, the importance of personal privacy

appeared overall high, with a mean of M=4.4

(SD=0.7). In this context, a significant gender effect

was found: the importance to protect one’s own

privacy was rated significantly (U=513, p=0.010)

higher by female participants (M=4.6; SD=0.6) than

by male participants (M=4.2; SD=0.8).

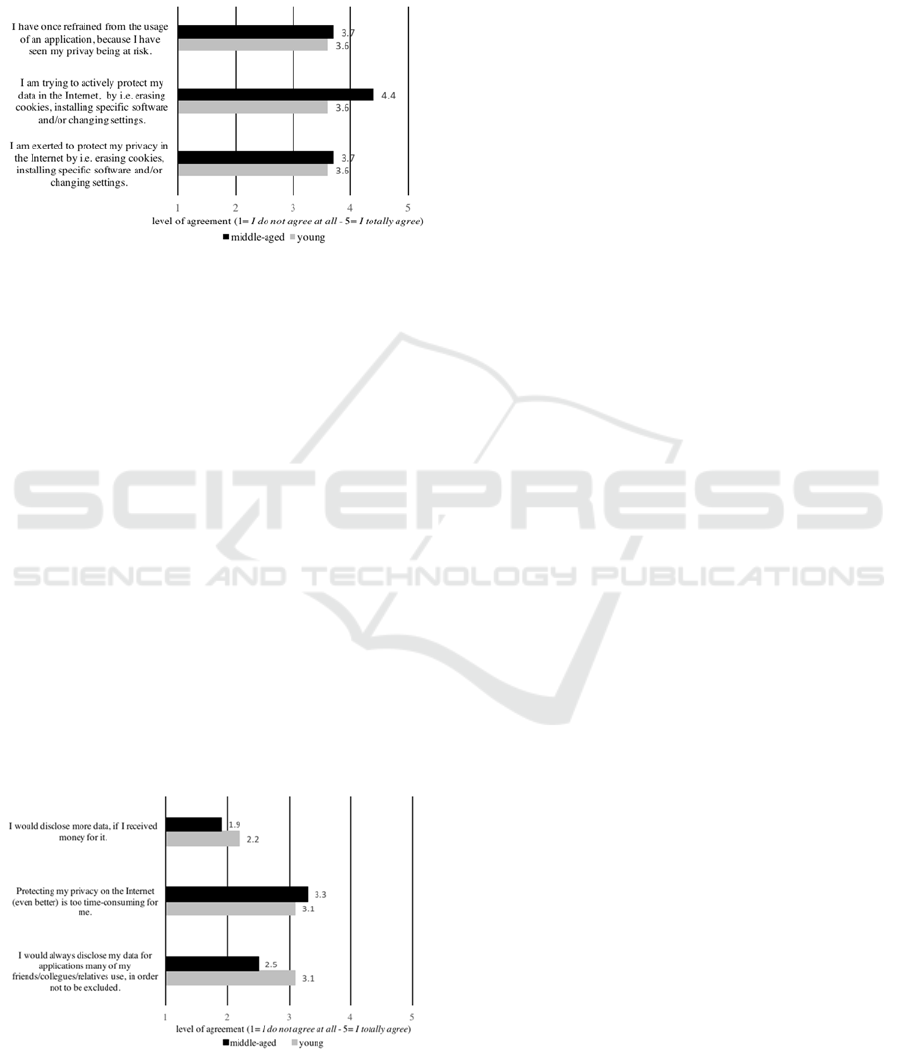

Protection Behaviors

When looking at the reported protection behaviors we

registered a high awareness of the importance of

protection behaviors. Participants reported to protect

their privacy by taking actions, such as erasing

cookies or installing specific software (M=3.7;

SD=1). Almost the same response pattern occurred

when asked about protection behavior regarding

personal data with a mean of M=4.2/5 points max

(SD=1). In addition, participants fully supported the

statement that they have once refrained from the

IoTBDS 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

86

usage of an application because they have seen their

privacy being at risk (M=4.2; SD=1.0) (Figure 7).

Interestingly, the protection behaviors were

comparably high in both, gender and age groups,

showing to be insensitive to user diversity.

Figure 7: Age comparison of data protection behaviors

(means) for younger (<28; N=35) and middle-aged persons

(>28 years; N=42).

Privacy Calculus

The results regarding aspects of the privacy calculus

are pictured in Figure 8. Asked about the time effort

participants would tolerate to protect their privacy

(“Protecting my privacy in the Internet (even better)

is too time-consuming for me.”) was mostly

confirmed (M=3.2, SD=1.1). However, the question,

if participants would disclose more information if

they received monetary compensation, was mostly

denied (M=2.0; SD=1.1). In this regard, again, female

and male as well as both age groups responded in the

very same way. A significant age difference (U=505;

p=0.014) was observed in the privacy calculus

regarding social pressure (“I would always disclose

my data for applications many of my friends use, in

order not to be excluded”). Here, younger

participants stated to rather disclose information in

order to stay socially connected with friends via

applications (M=3.1, SD=1.0) while participants

Figure 8: Age comparisons with respect to the privacy

calculus for younger (<28; N=35) and middle-aged

persons (>28 years; N=42).

belonging to the middle-aged group (M=2.5, SD=1.0)

were less willing to do so. No gender effects were

found (Figure 8).

5 DISCUSSION

In this paper, we sought to shed light on the

“phenomenon” of privacy perceptions and the

importance of data protection, exclusively taking a

user-centered perspective. The overall research focus

was directed to the question to what extent people are

aware of personal information they leave behind and

in how far they have a cognizant mental concept of

the attributed importance of particularly sensitive

data. Moreover, it is investigated in how far people

are concerned about their information privacy and for

what kind of benefit people decide to disclose

information.

In a first step, focus groups were run, in which we

analyzed users’ awareness of data footprints in the

Internet, type of data, and conceptions of different

sensitivity categories of data. As focus groups intent

to understand individual habits, predominately

qualitative data was collected. In a second step, an

online questionnaire was sent out in which privacy

attitudes, and behaviors in the context of data

disclosure vs. protection was quantitatively

determined. Findings were analyzed with a diversity

focus, thus, comparing gender and age groups

respecting privacy attitudes and behaviors.

As participants, we focused predominately on the so-

called “Digital Natives” which are described as a

generation that has spent their entire lives surrounded

by and using computers and digital applications

(Prensky, 2001). This generation is assumed to have

a “natural” relation to using digital media and to have

a quite elaborated practise and experience. In order to

see if digital natives behave and think differently we

had a somewhat “older” control group in the

questionnaire study (30-66 years of age).

Insights won from the focus group study show that

participants are not cognizant about their digital

footprints. While personal data are rather prominent

in participants’ mind as sensitive, data types that are

more “invisibly” collected, such as location data,

usage behavior, or interests are to a lesser extent

mentally represented as digital footprints. Basically,

participants seemed to be aware of privacy as a

general good and regarded it as a societally important

phenomenon, but when it came to the personal

relations of themselves and digital footprints,

participants had some difficulties to connect personal

Perceptions of Digital Footprints and the Value of Privacy

87

habits and digital behaviors, overall hinting at a low

personal awareness of data footprints.

It seemed that only with the help of extra stimuli

(pictures and video sequences) participants did start

to contemplate and think about it more strongly.

To sum up the focus groups’ findings, we

observed a diffuse picture. When directly asked for

the importance privacy and data protection,

participants attached high importance to both.

Digging deeper, it was found that participants seemed

to have only rudimentary awareness for their own

behaviors, as if young users lack reflection on their

own behaviors (Bennett et al., 2008). However, due

to the small sample size in focus group studies, we

cannot generalize these findings as typical for the

whole group of digital natives but should validate

these findings with a larger sample size. The task to

categorize data types considering sensitivity was also

not easy to accomplish for the participants, as the idea

of “sensitivity of data” was not an obvious one.

Finally, four central aspects were developed by focus

group participants which were mentioned to have an

impact on the decision to disclose data: (1) the

receiver of the information (science (tolerated) vs.

companies or insurances (not tolerated)) (2) the

purpose of information collection (benefit for society

(tolerated) vs. e-commerce or data malpractice (not

tolerated)), (3) the context of disclosure (health data

(tolerated) vs. information collected by third parties,

the government (not tolerated)), and (4) familiar

practices to what information is already or rather

usually known (clubmembership, age (tolerated) vs.

passwords, bank data (not tolerated)).

When looking into argumentation lines,

participants stressed that they wish to protect their

data, want to control who might have access to the

data but still, social (being part of a group) or

technical (accessibility, efficacy) benefits outweigh

their decisions of sharing data. It turns out that

participants seldom consciously realize what kind of

information they factually disclose. It is much more

that convenience and attractiveness of applications

are more prominent, deflecting attention from the

awareness which data footprints they leave behind.

Moreover, social incentives offered by social media

(e.g., the benefit of belonging to a group) outweigh

the potential risk of disclosing personal data,

corroborating earlier findings (Hui, 2006; Morando

et al., 2014; Kowalewski et al., 2015).

When looking to the outcomes in the

questionnaire study, again, it was corroborated that

persons attach a high importance to privacy and data

protection as a general good. This is true for the whole

sample, still, privacy is significantly more important

to female users in comparison to men.

Active protection behaviors were reported by all

participants, however, protection behaviors turned

out to be age-sensitive. On the one hand, middle-aged

users report to have a stronger protection behavior

(changing settings, using protection software) in

contrast to younger users. On the other hand, younger

persons are more willing to disclose their data

whenever they have the chance to stay connected with

their peers in contrast to middle-aged users which are

more reluctant in this regard. Thus, when it comes to

social adjustments, younger participants perform a

calculus between the expected loss of privacy and the

potential gain of disclosure and finally decide for the

social aspect and against the potential risk of privacy

loss (Debatin, 2009).

While the social reason to stay connected is a

strong argument for disclosing data, a potential

monetary reward is not perceived as attractive. On the

contrary, the whole sample rather denies that getting

money back (for data disclosure) would change

attitudes and behaviors. This is an interesting finding

as the relation between monetary rewards and data

protection or disclosure is well-known. In daily life,

many shops offer pay back benefits for data

disclosure and many people use it frequently. Also,

there is experimental evidence that monetary

incentives motivates people to disclose more data

(Carrascal et al., 2013) or, inversely, lead persons to

pay extra money in order not to disclose data and keep

their privacy (Beresford et al., 2012). Future studies

will have to explore under which circumstances data

disclosure can be motivated by different kinds of

monetary rewards and which persons might be

especially attracted by financial benefits in the

context of privacy and data protection.

6 LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE

RESEARCH DUTIES

Even though the study revealed first findings into

users’ awareness of digital footprints, and underlying

attitudes and behaviors in the context of data

protection, still, outcomes represent only a first

glimpse into a complex topic.

A first limitation regards the methodology used.

Focus groups and questionnaire assess users’

attitudes and beliefs with respect to a certain topic,

however, it is questionable if attitudes mirror what

people actually do when it comes to data disclosure

in real digital usage contexts. Here, experimental

studies could be helpful in which persons decide

IoTBDS 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

88

under which conditions and usage contexts they share

their data. A second research duty regards the

question how effective education programs regarding

digital awareness and digital protection behaviour

have to be designed. Delivering information only

seems to be of limited power - as persons “know”

much about the importance of privacy and the risk of

malpractice in the context of Big data. However, they

are not able or not willing to relate the knowledge to

their own behaviors. Therefore, practical,

demonstrative and concrete training programs should

be developed which allow persons to see and feel

consequences of their digital traces in the Internet,

thereby possibly influencing their digital behaviors to

the better. This could be of specific educative benefit

not only for younger people, but also for the digital

immigrants (Prensky, 2001), older Internet users,

which need to be supported in using digital media

correctly.

From a didactic point of view, it is a basic

question how concrete trainings programs should be

in order to provoke a cognizant attitude towards

Internet behaviours in general and privacy-sensitive

behaviors in particular. Definitively, it is not enough

to merely inform persons about risks, as from a

psychological point of view the relation between

benefits and risks is complex and considerably

impacted by affective usage motives (Alhakami,

1994).

Many learners refuse to respond to dictating tutor

systems with a superior attitude in the sense “you

should” or “you must”. Therefore, privacy behaviors

need to be mediated by quite seamless assistant which

let the users know about their current digital traces

and how valuable the data might be for external or

illegal access.

A running project funded by the German Federal

Ministry of Education and Research seeks to support

digital citizenship (responsible and mature behaviors

with digital data and services). “Mynedata”, the

project which we are involved in, catches up on the

situation that many Internet companies make money

through the re-utilisation of personal user data of their

customers. Usually, the individual user has no chance

to control the utilization of his/her data and receives

none of the generated profit. The idea of the project is

to offer a technical solution which turns the use and

exchange of personal data in a more transparent

process and allows the individual user a more self-

confident attitude in the digital world. Therefore, we

are currently exploring on a kind of data-cockpit

which allows users to manage the disclosure of own

data more consciously in all online services and

digital applications. The project pursues three aims:

first of all, data needs to be protected adequately.

Individually adjustable procedures of anonymising

data and privacy warranties are developed. For this

reason, the cockpit is supposed to offer the user a

classification of own data types into sensitivity grades

or rather privacy protection grades. First sensitivity

tendencies could already be found in this reported

research. Secondly, the user perspective receives

special interest. Right from the beginning a user-

centred design is chosen, to develop the technical

solution according to the user’s needs. Research

findings of empirical user studies are immediately

entering the technical development of the cockpit. A

third aspects lies in the individual profit of data

transfer. Disclosure of personal data is supposed to be

rewarded with a benefit e.g. in a monetary kind. That

way not only businesses profit from data disclosure

but also users, the actual data owners itself. At the

moment a study is running, investigating on the

acceptance and the different functions regarding the

privacy protection such a cockpit should contain.

Besides the scientific user perspective point of view,

also technical and security related, as well as juristic

and economic aspects are considered and taken into

account for the interdisciplinary approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all participants for sharing their experience

and thoughts and we thank Sarah Völkel and

Katharina Merkel for valuable research support. This

project is funded by the German Ministry of

Education and Research (BMBF) under project

MyneData (KIS1DSD045).

REFERENCES

Acquisti, A., Brandimarte, L., and Loewenstein, G. (2015).

Privacy and Human Behavior in the Age of

Information. Science, 30(6221), 509–514.

Acquisti, A., and Grossklags, J. (2005). Privacy and

rationality in individual decision making. IEEE

Security and Privacy, 3(1), 26–33.

Acquisti, A., and Gross, R. (2006). Imagined Communities:

Awareness, Information Sharing, and Privacy on the

Facebook. International Workshop on Privacy

Enhancing Technologies, Springer, Berlin, 36–58.

Alhakami, A. S., and Slovic, P. (1994). A psychological

study of the inverse relationship between perceived risk

and perceived benefit. Risk analysis, 14(6), 1085-1096.

Altman, I. (1975). The environment and social behavior.

Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Bansal, G., Zahedi, F. M., and Gefen, D. (2010). The

Perceptions of Digital Footprints and the Value of Privacy

89

Impact of Personal Dispositions on Information

Sensitivity, Privacy Concern and Trust in Disclosing

Health Information Online. Decision Support Systems,

49(2), 138–150.

Bennett, S., Maton, K., & Kervin, L. (2008). The ‘digital

natives’ debate: A critical review of the

evidence. British journal of educational

technology, 39(5), 775-786.

Beresford, A., Ku

̈

bler, D., and Preibusch, S. (2012).

Unwillingness to pay for privacy: A field experiment.

Economics Letters , 117, 25-27.

Boyd, D., and Hargittai, E. (2010). Facebook privacy

settings: Who cares? First Monday, 15(8), 13–20.

Brandimarte, L., Acquisti, A., and Loewenstein, G. (2012).

Misplaced Confidences: Privacy and the Control

Paradox. Social Psychological and Personality Science,

4(3), 340–347.

Brecht, F., Fabian, B., Kunz, S., and Mueller, S. (2011,

June). Are you willing to wait longer for internet

privacy? In: European Conference on Information

Systems (no page numbering).

Carrascal, J. P., Riederer, C., Erramilli, V., Cherubini, M.,

and de Oliveira, R. (2013, May). Your browsing

behavior for a big mac: Economics of personal

information online. In Proceedings of the 22nd

international conference on World Wide Web (pp. 189-

200). International World Wide Web Conferences

Steering Committee.

Chakraborty, R., Vishik, C., and Rao, H. R. (2013). Privacy

Preserving Actions of Older Adults on Social Media:

Exploring the Behavior of Opting out of Information

Sharing. Decision Support Systems, 55, 948–956.

Cho, H., Lee, J.S,and Chung, S. (2010). Optimistic bias

about online privacy risks: Testing the moderating

effects of perceived controllability and prior

experience. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 987-

995.

Data protection Eurobarometer. (2015). Gov.Uk.

Debatin, B., Lovejoy, J. P., Horn, A. K., & Hughes, B. N.

(2009). Facebook and online privacy: Attitudes,

behaviors, and unintended consequences. Journal of

ComputerMediated Communication, 15(1), 83-108.

Dinev, T., and Hart, P. (2003). Privacy Concerns And

Internet Use– A Model Of Trade-Off Factors. Academy

of Management Proceedings, 2003(1), D1–D6.

Dinev, T., and Hart, P. (2006). An Extended Privacy

Calculus Model for E-Commerce Transactions.

Information Systems Research, 17(1), 61–80.

Heise, D. R. (1970). The semantic differential and attitude

research. Attitude measurement, 235-253.

Helsper, E. J., and Eynon, R. (2010). Digital natives: where

is the evidence? British Educational Research

Journal, 36(3), 503-520.

Hui, K., Tan, B., and Goh, C. (2006). Online Information

Disclosure: Motivators and Measurements. ACM

Transactions on Internet Technology, 6(4), 415–441.

Kehr, F., Kowatsch, T., Wentzel, D., and Fleisch, E. (2015).

Blissfully ignorant: The effects of general privacy

concerns, general institutional trust, and affect in the

privacy calculus. Information Systems Journal, 25(6).

Kehr, F., Wentzel, D., and Mayer, P. (2013). Rethinking the

Privacy Calculus: On the Role of Dispositional Factors

and Affect. The 34th International Conference on

Information Systems, (1), 1–10.

Keith, M. J., Thompson, S. C., Hale, J., Lowry, P. B., and

Greer, C. (2013). Information disclosure on mobile

devices: Re-examining privacy calculus with actual

user behavior. International Journal of Human-

Computer Studies, 71(12), 1163-1173.

Kokolakis, S. (2015). Privacy attitudes and privacy

behaviour: A review of current research on the privacy

paradox phenomenon. Computers and Security,

2011(2013), 1–29.

Kowalewski, S., Ziefle, M., Ziegeldorf, H., and Wehrle, K.

(2015). Like us on Facebook!–Analyzing User

Preferences Regarding Privacy Settings in Germany.

Procedia Manufacturing, 3, 815-822.

Krasnova, H., and Veltri, N. F. (2010, January). Privacy

calculus on social networking sites: Explorative

evidence from Germany and USA. In System sciences

(HICSS), 2010 43rd Hawaii international conference on

(pp. 1-10). IEEE.

Lewis, K., Kaufman, J., and Christakis, N. (2008). The taste

for privacy: An analysis of college student privacy

settings in an online social network. Journal of

Computer-mediated Communication, 14(1), 79–100.

Li, H., Sarathy, R., and Xu, H. (2010). Understanding

situational online information disclosure as a privacy

calculus. Journal of Computer Information Systems,

51(1), 62–71.

Mayring, P. (2001, February). Combination and integration

of qualitative and quantitative analysis. In Forum:

Qualitative Social Research (Vol. 2, No. 1).

Morando, F., Iemma, R., and Raiteri, E. (2014). Privacy

evaluation: what empirical research on users' valuation

of personal data tells us. Internet Policy Review, 3(2),

1-11.

Morton, A. (2013, September). Measuring inherent privacy

concern and desire for privacy-A pilot survey study of

an instrument to measure dispositional privacy concern.

In Social Computing (SocialCom), 2013 International

Conference on (pp. 468-477). IEEE.

Mothersbaugh, D. L., Foxx Ii, W. K., Beatty, S. E., and

Wang, S. (2011). Disclosure Antecedents in an Online

Service Context: The Role of Sensitivity of

Information. Journal of Service Research, 1–23.

Norberg, P. A., Horne, D. R., and Horne, D. A. (2007). The

Privacy Paradox: Personal Information Disclosure

Intentions versus Behaviors. The Journal of Consumer

Affairs, 41(1), 100–126.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants part

1. On the horizon, 9(5), 1-6.

Rainie, L., Kiesler, S., Kang, R., Madden, M., Duggan, M.,

Brown, S., and Dabbish, L. (2013). Anonymity,

privacy, and security online. Pew Research Center, 5.

Schoeman, F. (1984). Philosophical dimensions of privacy.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sheehan, K.B. and Hoy, M.G. (2000). Dimensions of

Privacy Concern Among Online Consumers. Journal of

Public Policy and Marketing, 19(1), 62–73.

IoTBDS 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

90

Smith, H. J., Dinev, T., and Xu, H. (2011). Information

Privacy Research: An Interdisciplinary Review. MIS

Quarterly, 35(4), 989–1015.

Special Eurobarometer 359: Attitudes on Data Protection

and Electronic Identity in the European Union. Report.

(2011).

Taddicken, M. (2014). The ‘Privacy Paradox’ in the Social

Web: The Impact of Privacy Concerns, Individual

Characteristics, and the Perceived Social Relevance on

Different Forms of SelfDisclosure. Journal of

ComputerMediated Communication, 19(2), 248-273.

TRUSTe. (2014). TRUSTe 2014 US Consumer Confidence

Privacy Report. Consumer Opinion and Business

Impact (Vol. 44).

Van den Broeck, E., Poels, K., and Walrave, M. (2015).

Older and wiser? Facebook use, privacy concern, and

privacy protection in the life stages of emerging, young,

and middle adulthood. Social Media+ Society, Advance

online publication.

Xu, H., Dinev, T., Smith, H. J., and Hart, P. (2008).

Examining the Formation of Individual’s Privacy

concerns: Toward an Integrative View. In International

Conference on Information Systems.

Xu, H., Dinev, T., Smith, J., and Hart, P. (2011).

Information Privacy Concerns: Linking Individual

Perceptions with Institutional Privacy Assurances.

Journal of the Association for Information Systems,

12(12), 798–824.

Warren, S.D., and Brandeis, L.D. (1890). The Harvard Law

Review Association. Harvard Law Review, 4(5), 193–

220.

Westin, A. (1967). Privacy and freedom. New York:

Atheneum.

Ziefle, M.; Halbey, J. and Kowalewski, S. (2016). Users’

willingness to share data in the Internet: Perceived

benefits and caveats. International Conference on

Internet of Things and Big Data (IoTBD 2016), pp. 255-

265. SCITEPRESS.

Perceptions of Digital Footprints and the Value of Privacy

91