Interaction in Situated Learning Does Not Imply Immersion

Virtual Worlds Help to Engage Learners without Immersing Them

Athanasios Christopoulos, Marc Conrad and Aslan Kanamgotov

Department of Computer Science & Technology, University of Bedfordshire, Luton, U.K.

Keywords: Immersion, Situated Learning, Virtual Worlds, OpenSim, Learner Engagement, Interaction, Teaching.

Abstract: Immersion is a central theme when using virtual worlds; the feeling of ‘being there’ is generally considered

a positive attribute of virtual worlds, in particular when these are used for recreation. However, within

educational context it may be debatable how far immersion can be expected or is even desirable: if we want

students to be reflective and critical on their assignment task, wouldn’t it be more important for them to

have a critical distance, rather than being immersed? In this paper, we approach this question by examining

and discussing how interactions, learner engagement and immersion are linked together when a virtual

world is being used in a Hybrid Virtual Learning scenario. Findings from our experiment seem to suggest

that even though this learning approach aids positively the educational process, high levels of immersion do

not occur. Nevertheless, more research in that direction is highly recommended to be undertaken.

1 INTRODUCTION

Immersion is often considered to be central to

Virtual Worlds (VWs) (Bredl et al, 2012; Childs,

2010; Christopoulos, 2013). However, it might be

debated how far immersion might help or hinder an

education experience within a university assignment.

While situated learning (Herrington and Oliver,

2000) is generally considered a futile approach to

facilitate practical student experience it may be

questioned if ‘too much’ immersion might hinder

students to critically reflect on their learning

experience. This is in particular relevant on

postgraduate level where this critical reflection is

typically a key learning outcome of the course.

In order to shed some light on this issue we draw

data from observations from an experiment

conducted in the wider context of student interaction

and engagement and re-interpret the findings in view

of the level of student immersion.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Interacting with Virtual Worlds

VWs provide the necessary context for different

types of interactions either between the users and the

content of the VW or the users themselves. Typical

examples of these types of interactions are the object

creation and manipulation (Bredl et al, 2012), terrain

editing (Allison et al., 2012), and navigating around

the world (Hockey et al., 2010). Communication is,

indeed, another important factor which increases the

opportunities for interaction between the users; be it

synchronous or asynchronous, verbal or written or

through the use of avatar gestures (Hockey et al.,

2010). VWs have been used in various paradigms as

they provide fertile ground for the implementation of

different learning styles (e.g. Problem Based

Learning, Exploratory Learning, and Distance

Learning) (Christopoulos, 2013). Vygotsky’s (1978)

Social Constructivist Learning Theory has great

practical application in VWs since it covers issues

such as the fact that students become active learners

while building, at the same time, their cognitive

structures and knowledge through the complex

network of interactions that motivate them to engage

with the VW and the learning material, by extension.

Indeed, as Jones (2013) suggests, learners have the

ability to actively affect, alter, and enhance the

content of the VW in a manner that will enable them

to construct their cognitive schemes and engage with

the subject they study. Zhao et al. (2010) further

extend the aforementioned claim and also suggest

that learning becomes more self-directed and

student-centered, whereas educators get the role of

Christopoulos, A., Conrad, M. and Kanamgotov, A.

Interaction in Situated Learning Does Not Imply Immersion - Virtual Worlds Help to Engage Learners without Immersing Them .

DOI: 10.5220/0006316203230330

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) - Volume 1, pages 323-330

ISBN: 978-989-758-239-4

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

323

instructional designers or supporters of activities that

aim to engage students in learning (Anasol et al.,

2012).

Educators’ new role has triggered the conduct of

several studies focusing on the interactivity of the

VWs and the in-world interactions that can – or need

to – be developed in order to cover students’

learning needs. Some studies investigate the use of

VWs in distance learning scenarios (de Freitas et al.,

2009) aiming to identify an evaluation method to

measure students’ learning experiences, while others

cover the skills students acquire when they start

using VWs (Childs, 2010). Another group of studies

focuses on the elements that affect a VW’s

interactivity (Steuer, 1992), whereas others

attempted to address the aforementioned topic from

a different perspective (Chafer and Childs, 2008) as

they identified additional parameters. However,

most of these studies disregard the perspective of

learning in the physical classroom in conjunction

with the VW (Camilleri et al., 2013).

Based on the review of the literature that we

have conducted, only a few studies attempted to

examine interactions both from the inside and from

the outside (Levesque and Lelievre, 2011) whereas

the authors suggest that great emphasis should be

given on the enhancement of interactions both in the

VW but also in the physical classroom. De Freitas et

al. (2010) also underline the importance and need for

further investigation of the potential and the

affordances of hybrid spaces with simultaneous

student physical and virtual presence. Other

researchers (Elliott et al., 2012) highlight the lack of

detailed taxonomy of all the interactions related to

the educational use of VWs, which would aid in a

better understanding of their affordances, in a more

expedient design of educational activities, and in a

more thorough exploitation of their potential.

2.2 Immersion in Virtual Worlds

Immersion, according to Brown and Cairns (2004),

denotes a “sense of being there” or a “Zen-like state

where your hands just seem to know what to do, and

your mind just seems to carry on with the story”. As

a phenomenon to describe the immersion experience

this is not something new and applicable only to the

VW. We can feel immersed while reading books

(Nell, 1988), watching films (Bazin, 1967) or doing

something else, no matter what but it needs to

involve us fully in order we, as “users”, could

achieve that state of the mind. With the relatively

recent advent of VWs, however, the phenomenon

described received a new momentum, involving the

user through not only observation of the material,

but while actively interacting with environment,

establishing the cybernetic circuit between the user

and the VW. This phenomenon is described as

“presence” and “immersion”. Though both

definitions are widely used and have been discussed

for decades, there seems to be a lack of consensus

achieved so far (Brown and Cairns, 2004).

Nevertheless, the phenomenon these two terms have

been enlisted to describe is crucial to our

understanding of the relationship between user and

VW, as it represents one end of a continuum of

intensity of involvement with VWs and addresses

the very notion of being in the context of such

simulated environments. As Calleja (2014) argues,

the main challenge and confusion between two terms

is “based on a number of challenges they pose to a

clear understanding of the phenomenon they have

been employed to describe”, since neither of the

terms fully and adequately describes the relationship

between the user and VW, assuming that the human

being interacts with the VW in a unidirectional

manner, that there is a certain split between the user

in his real world (“here”) and the virtual counterpart

he interacts with (“there”). Both definitions,

“presence” and “immersion”, are used frequently

and interchangeably, though there is a certain level

of contradiction between them. Slater and Wilbur

define immersion as a technological feature, an

option which belongs to the side of “technicalities”,

rather than the state of the mind: “A description of a

technology […] that describes the extent to which

the computer displays are capable of delivering an

inclusive, extensive, surrounding and vivid illusion

of reality to the sense of a human participant” (Slater

and Wilbur, 1997). In contrast, Witmer and Singer

(1998) describe the immersion as “a psychological

state characterized by perceiving oneself to be

enveloped by, included in, and interacting with an

environment that provides a continuous stream of

stimuli and experiences”, which aligns quite closely

to Slater and Wilbur’s definition of “presence”.

Moreover, Calleja (2014) introduces a “more

productive and precise” definition, where “the VW

assimilated into the user’s consciousness as a space

that affords the exertion of agency and expression of

sociality in a manner coextensive with our everyday

reality” which he calls “Incorporation”.

While the exact definition of ‘immersion’ is still

open to debate we note that it is (in any definition) a

central theme and expected outcome when

interacting with virtual worlds. The evaluation of

which of the definitions describes the phenomenon

more precisely lies beyond the scope of this research

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

324

and in order to avoid further confusion in the

terminology, the term “immersion” is used

throughout, denoting the user’s involvement into his

activities within a virtual environment.

3 MATERIALS & METHODS

To investigate the relationship between interaction

and immersion we draw data from an experiment

which lasted one month involving postgraduate

Computer Science & Technology students

participating in the study. Indeed this experiment is

part of a wider study on how different types of VWs

help or hinder student engagement.

Figure 1: Snapshot of the content of the virtual world

which has been developed for the needs of the experiment.

An institutionally hosted OpenSimulator VW was

used for students to work with the built-in

programming language and design 3D objects. At

the end of this assignment, all student groups were

expected to present their work, prepare a video about

their virtual showcase and submit a report. This class

was being held, besides the traditional lecture form,

in two-hour practical sessions which ran once a

week. Finally, the focus of this experiment was to

examine the impact that the educational and leisure

games have on interactions, learner’s engagement

and consequently immersion (see Figure 1).

3.1 Research Methodology

Research through observation may have several

strengths but three were the main aspects that

indicated observation as the most suitable method

for this study. Firstly, as described in Cohen et al.

(2011), that led to the emergence of unique primary

data, the most essential advantage of observation is

considered to be the principles of ‘immediate

awareness’ and ‘direct cognition’ — i.e. the

opportunity given to a researcher to have a ‘direct

look’ at the actions that take place without having to

rely on second-hand accounts. Secondly, observation

is a very flexible form of data collection that allows

researchers to alter their focus, depending on the

observed actions and behaviours. Finally, the

method of observation allows the researcher to

gather any necessary data, while the participants

unimpededly follow their own agenda and priorities.

Nevertheless, when conducting observation

research, there are unavoidably – as with most

methods – certain disadvantages in the data

collection process. Even though a great effort was

made to eliminate them as much as possible, they

cannot be disregarded. In particular, the main

challenge, when collecting primary data through

observation, is the ‘selective attention of the

observer’. In addition, the ‘reactivity’ of the sample

can also run the risk of bias. Finally, observations

are recording only what happens in a given period of

time or what can be seen in a given interface.

4 LEARNER ENGAGEMENT,

INTERACTIONS &

IMMERSION

In order to identify the impact that different types of

interactions have on users – or in this case students –

while being (physically) present in a university

laboratory and also in the VW, we developed our

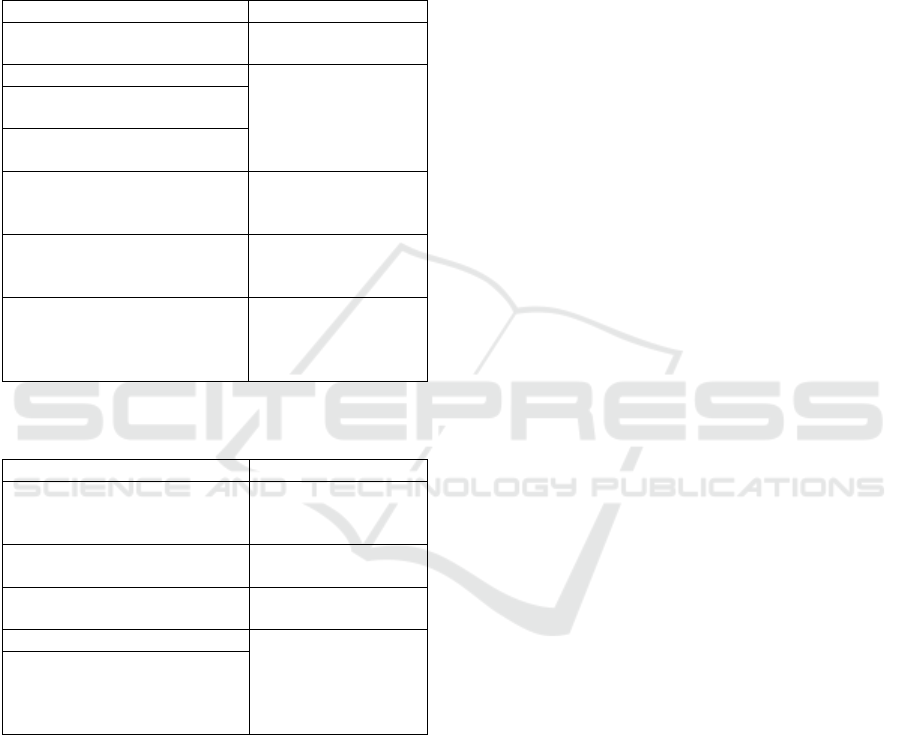

own observation checklist (see Tables 1 and 2). The

focus points – though not all of them are presented

in this paper as we are focusing exclusively on those

who have impact on immersion – were developed

after using the findings of a research conducted by

one of the authors (Christopoulos, 2013), under the

principles and guidelines of the Grounded Theory

(Strauss and Corbin, 1998) and the suggestion of

pedagogists on how to make these observation

checklists effective (Cohen et al., 2011).

Consequently, we correlated these focus points

in accordance with the framework related to the

factors affecting immersion as presented by Witmer

and Signer’s (1998), and namely are:

Control Factors: such as ‘degree of control’,

immediacy of control’, ‘anticipation of events’,

‘mode of control’, ‘physical environment

modifiability’

Sensory Factors: such as sensory modality,

environmental richness, multimodal presentation,

consistency of multimodal information, degree of

Interaction in Situated Learning Does Not Imply Immersion - Virtual Worlds Help to Engage Learners without Immersing Them

325

movement perception, active search

Distraction Factors: such as isolation, selective

attention, interface awareness

Realism Factors: scene realism, information

consistent with objective world, meaningfulness

of experience, separation anxiety / disorientation.

Table 1: Observation checklist (actions & interactions in

the physical classroom) and linkage to level of immersion.

Type of interaction Immersion

Student seems focused on his/her

project

High (meaningfulness

of experience)

Student seems “absent-minded”

Inconclusive

Student seems to enjoy the

project

Student seems unpleased using

the VW

Student makes positive/negative

comments about the technology

or emotional experience.

Low (detached from the

VW to interact in the

real)

Student refers to avatar in the

first person/ identifies with avatar

(avatar as ‘I’)

High (embodiment)

Student refers to avatar in the

second person/ addresses avatar

directly (‘you’), third person

(‘him’, ‘her’ or as an object (‘it’)

Low (demonstrates

distance)

Table 2: Observation checklist (actions & interactions in

the VW) and linkage to immersion.

Type of interaction Immersion

Student works on project

(building/scripting)

High (physical

environment

modifiability)

Student refers to avatar within

VW.

High (indicates

interaction)

Student modifies his/her

avatar’s appearance

Inconclusive (might

indicate distance)

Student uses avatar gestures

High (as it happens

in-world, rather than

direct interaction

with classmates)

Student uses existing content,

in-world tools, his/her own

virtual creations, explores

classmates’ virtual artifacts

5 REFLECTION ON THE

OBSERVED DATA

In this Section we will discuss the actions that

students performed during their practical sessions as

they have been observed by the researcher, both in

the physical classroom and the VW, during the

course of this experiment. In order to observe all the

participants for an equal amount of time, students’

actions were logged in rotation for approximately 30

seconds (per student or pair of students) until the

completion of the practical session. In total, 18

students participated in our study among which

fifteen (15) were males and 3 (females).

5.1 Actions & Interactions in the

Physical Classroom

5.1.1 Student Attitude towards the Use of

the VW

Week 1. Most of the students dedicated their time to

explore the content of the VW, play with the games

(amusement park, lake, café, maze), discover and

familiarise themselves with the tools of the VW, and

only a few of them – almost at the end of the

practical session – were observed being at their

team’s workspace in order to discuss, plan and make

some initial design of their project’s infrastructure.

Indeed, as it was as introductory session and most of

the students were not familiar with the building and

scripting tools of the environment, they were not

expected to be either working right away or to be

focused on their project. A couple of students were

quite often observed being absent-minded or

completely detached from the VW, as they were on

their phones or staring at their friends without

actively engaging or participating in the

conversations. The main source of disappointment or

displeasure was the difficulty some students had in

understanding the tools of the VW (even the

navigational ones). As a general note, it is worth

mentioning that all of them acknowledged the

importance of having pre-existing content in place,

as it provided them with the opportunity to get a

taste of what their simulation or showcase should

contain or look like.

Week 2. Almost all the students (including some

of them who were responsible for the development

of the virtual showcase) spent a considerable amount

of time (in total duration) working or helping their

teammates with the documentation needs of their

project. However, most of the developers were

usually interacting more with the VW and less with

their team members who were working on other

aspects of the project. Nevertheless, as most of them

(the developers) were still not comfortable with the

building and scripting tools of the technology, very

few of them, and only for a few times, were

observed working ‘focused’ on their project. Indeed,

the difficulty most of the students had manipulating

the tools of the VW was undoubtedly a good reason

to be displeased or even frustrated (in some cases).

Likewise, very few times were students observed

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

326

being happy or enjoying the process, as they were

not directly engaged with the actual development

process, but, instead, they were trying to deal and

familiarise with the tools of the VW.

Week 3. All the teams but one (infancy stage)

had shown some actual effort to work and develop

parts of their virtual showcase as they had now

reached the middle-end stage of their projects.

During the course of the practical session, all of the

developers were most of the time located at their

teams’ workspaces, working on their projects.

However, very few times were students observed

working focused on their task, as they were often

distracted by other matters (talking, helping,

searching on the web). Likewise, no great levels of

enjoyment were observed, as the students were

trying to do some serious work without losing time

in playing or entertaining themselves along the way.

A couple of students were observed a few times

being absent-minded or actually completely

detached from the VW (use of mobile phone), while

some more students were quite displeased, as they

were still struggling a lot to understand the tools of

the VW. As these students were part of the

aforementioned team that was still in an infancy

stage, their disappointment turned into frustration

and anger towards the use of the VW, leaving no

space for other students or the teaching team to help

them out.

Week 4. Even though all the students were

working on the finalisation of their virtual showcase,

very few times were they observed working focused

on their projects. In fact, quite often their attention

was being distracted by other matters such as the

documentation process. Apart from not being

focused on their task, a group of three students were

observed being several times completely detached

from the VW, as they were browsing the news on

the web, staring at other students or using their

phones. Not very obvious levels of enjoyment were

observed either. Most of the students were rushing to

finish off the development of their showcase or to

make some ‘last-minute’ modifications on their

objects, while also offering some help to other team

members that were working on other matters.

5.1.2 Student Identity and Avatar Identity

Week 1. Students that managed to familiarise

themselves with the VW faster than others were

quite keen to help their fellow students to perform

some, at least, basic changes in their avatars’

appearance editing, and, thus, a large portion of the

session’s time was centred around this process.

Indeed, several comments were made by most of the

students, such as ‘why am I a lady?’, ‘I want to be a

man, how do I change my gender?!’, ‘he is very

ugly, how we can fix it?’, ‘can I make it black like

me?’, ‘get a brush and start painting it bro! haha!’. A

fairly common and often repeated action was the

observation of students pushing their avatars to go

far beyond the VW’s ‘invisible’ borders, something

which caused their avatars to seem stuck or gave the

illusion of flying to ‘nowhere’. As expected, help

requests to ‘unstuck’ the avatars were made to the

teaching team ‘he lost his way [referring to his own

avatar]! Can you help me get back to ground?’.

Interestingly, one of the students lost his way out

while visiting one of the workspaces and asked the

lab demonstrator to help him find his way out ‘sir, I

got myself in this room, how can I go out?’.

Week 2. Very few students were observed

modifying their avatars’ appearance for a fairly short

period of time, whereas equally rare were the

references made in relation to them. A quote worth

mentioning was the one made by one of the students

asking his life-partner, and eventually fellow

student, to modify his own avatar as he was

struggling to do so ‘[partner’s name] can you make

it look like me?’. Another interesting comment was

made by the only student who slightly ‘drifted’ from

the mainstream attitude that most students had

towards their avatars, i.e. mirroring their physical

identity in the VW, and differentiated himself by

modifying his avatar’s body shape in a completely

different way, completely opposed to his physical

identity (overweight-underweight) ‘guess I need to

start training! Lol’.

Week 3. Only two students were observed

modifying their avatars’ appearance. However, both

of them performed minor changes for an overall

short period of time. In particular, one of them was

observed making modifications mainly for his own

favour and desire, whereas the second one was

performing changes that were required for the needs

of his team’s showcase (demonstration of smart

devices attached to human body or, in this case, the

avatar’s body). In any case, very few references

related to avatars were observed mainly during the

natural talk-flow, and, interestingly, all of them in

the second person ‘poseballs can help you do it’,

‘You need to attach it in your left shoulder otherwise

it is not going to work’, ‘Where are you going?’.

Week 4. None of the students was observed

making direct reference or mention to avatars at any

point during the practical session. However, one

student was observed editing his avatar’s appearance

for a couple of minutes, for the needs of the

Interaction in Situated Learning Does Not Imply Immersion - Virtual Worlds Help to Engage Learners without Immersing Them

327

showcase demonstration.

5.2 Actions & Interactions in the VW

5.2.1 Student Identity and Avatar Identity

Observation week 1. Almost all the students were

observed modifying their avatars’ appearance for a

considerable amount of time. Some of them

performed basic changes, such as hair and body

style, whereas others made some more detailed and

intensive one, such as clothing and accessories.

Interestingly, none of the students were observed

role-playing (opposite gender than their real one or

converting their avatar into something unrealistic

e.g. robot, animal). However, several students

modified their avatars’ appearance according to their

desire, without mirroring their real identity (physical

condition). As the use of the chat tool was quite

intense, several times students were observed

referring to avatars through it.

Week 2. As the use of the chat tool was almost

non-existent, no comments about avatars were

observed. Likewise, only a few students were

observed modifying their avatars’ appearance, with

the most striking examples being the appearance

editing made by one of the students on behalf of her

friend, and the student that slightly role-played by

modifying his avatar’s body shape to look

differently than his physical one.

Week 3. Only two students were observed

modifying their avatars’ appearance. However, none

of them performed extreme or unrealistic

modifications. In particular, one of them made some

basic changes whereas, the other one, who was

performing modifications on the avatar’s appearance

in order to be used as part of the showcase

demonstration, spent a considerable amount of time

carefully editing body parts as the project of his

team was dealing with the development of a

smart/security vest for cyclists. In any case, none of

the students was observed using the chat tool to

make references or mentions to avatars at any given

time.

Week 4. Only one student was observed working

on the modification of his avatar’s appearance in

order to attach and correctly position the finalised

scripted objects that were meant to be used for the

demonstration of this team’s showcase. As regards

the chat tool, some very inappropriate comments

(considering the university context) were observed

being made by two students while commenting on

the avatars of other students. It is, however, quite

interesting to know and ponder on the fact that even

though students were aware of being observed in

real-time as well as of the existence of chat-logs,

they still decided to use the in-world chat tool to

make a rather inappropriate conversation.

5.2.2 Interactions with the World

Week 1. Only a few students were observed working

or, more precisely, making some preliminary work

related to their project for a couple of minutes just

before the end of the practical session. Instead,

students’ attention almost monopolised by the

content exploration and use (developed by other

students/the researcher), the modification of their

avatars’ appearance, and the exploration of the in-

world building tools. Indeed, most of the students

spent a considerable amount of time exploring the

content that had been developed by other students,

visited and played with the games located at the

amusement park, the mini lake and the café, though

only one student was observed going through the

maze. In any case, none of the students/teams was

observed using or even being at the racing game. As

to the exploration of the in-world tools, almost all

the students exchanged friend requests both with

their team members and their fellow students, and

used the chat tool including the Instant Messages

option. After being suggested by the lecturer, all the

teams were observed setting up their own group

(using the in-world function) and some students

further explored the tools of the VW (e.g. weather

settings, gestures). As far as the building tools are

concerned, nearly all the students were observed

using and editing some of the default library prims

in order to better understand their capabilities,

without, however, spending a considerable amount

of time modifying them in a meaningful way. On the

other hand, none of the students was observed

exploring the programming language even though a

mention was made by the lecturer.

Week 2. At the starting point of the practical

session, most of the students were observed

wandering around the showcases developed by

others, in order to observe and discuss their

functionality and get some ideas for their own work.

However, all of them were quite sceptical and

uncertain regarding the development process of their

own showcases, due to the fact that they were still

very unfamiliar with the development tools of the

VW. Thus, a considerable amount of time, during

the practical session, was dedicated for

experimentation with the primitives that could be

found in the in-world library, the importing process

of textures and objects and, in some cases, even of

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

328

scripts (mostly premade ones that can be found on

the web). After reaching half-way of the practical

session, some students became keener to use objects

developed by their class or team mates, to request

some feedback or help from others and to teach

others what they had discovered (peer-tutoring/peer-

learning). It is worth mentioning that none of the

students was observed approaching, visiting or using

the content developed by the instructional designer

at all, or performing in-world actions irrelevant to

their project, other than some avatar appearance

modification. Finally, a couple of students that were

observed roaming quite often to other workspaces

discovered and used the landmark tool, which

allowed them to ‘mark’ several locations on the

virtual map and, so, they could instantly teleport

back and forth.

Week 3. Overall, it was a fairly ‘silent’ in-world

observation as students were working focused on

their task without being disrupted too often. This can

be justified by the fact that only one week had been

left prior to the submission of their assignment and,

by extension, the completion of their virtual

showcase and, thus, all of them had to hurry towards

the final implementation and development of their

showcases. The relatively few times during which

students were observed performing actions irrelevant

to their project, included visits to other workspaces

and use of the scripted objects developed by others.

It is worth mentioning that none of the students was

observed visiting the content developed by the

researcher at any time.

As far as the tools of the VW are concerned, the

group function was proved to be quite helpful and

handy for most of the developers, as they could edit

and/or remove objects that other team members had

created during the past days. In addition, even

though a notable mention regarding poseballs was

made in the physical classroom, only one team

showed intense interest to use them in order to

animate their avatars.

Week 4. Very few times were students observed

performing in-world actions irrelevant to their

project, such as visiting the workspaces of other

students, or using the content developed by the

researcher (actually, the latter was never observed).

Indeed, very few students and for a small period of

time were observed wandering around the

workspaces of their virtual neighbours, though

without using anything located there but only

observing. Instead, most of them were usually

located at their own workspaces, finalising their

showcases by adding cosmetic primitives or scripts.

Only one group was observed missing important

elements from their showcase, as they were fairly

behind the schedule and a considerable amount of

work had to done for its completion.

6 DISCUSSION & CONCLUSIONS

The main advantage of the Hybrid Virtual Learning

approach is that it eliminates the drawbacks and the

disadvantages that each one of the two educational

methods, i.e. the virtual and the traditional

classroom learning, have. However, this has a

critical effect on the levels of immersion that

students can reach due to the different types of

stimuli they get from the physical classroom, the

online (outside of the VW) available resources (as

part of their research for their assignment) or even

aspects related to their personal life and are

completely unrelated to university (social media,

phone-calls and texts).

Even though students had quite intense

interaction with the content of the VW and its tools,

especially during their first contact with the world,

the levels of immersion were almost non-existent

due to the often breaks they have had to discuss their

in-world actions with their fellow-students in the

physical classroom. Likewise, the parallel actions

that most of the students were usually performing be

it to help their fellow-students with other tasks or to

provide some help (demonstrate) to those who were

struggling to cope with the VW and its tools were

also decreased the levels of immersion.

Finally, the fact that students were working over-

focused on their task during the final stages of their

assignment, can also not be considered as an

indication of high levels of immersion given that

most – if not all – of them were stressed and anxious

to complete their in-world task so that they could get

all the bits and pieces of their assignment together

and submit their work.

We may therefore conclude that immersion does

not seem to have much – if any – relevance when it

comes to educational practices as opposed to virtual

games. Even though in both cases in-world goals

and targets are to be achieved (students want to

complete their assignment in order to get ‘real’

marks and gamers want to complete a set of tasks in

order to get the feeling of completion or joy), using a

VW – even with game-like content – as an extension

of the physical university does not lead students to

encounter high levels of immersion.

Counterintuitively, this lack of immersion might

well be a plus. It may lead to a useful distance

between the student and their in-world task and

Interaction in Situated Learning Does Not Imply Immersion - Virtual Worlds Help to Engage Learners without Immersing Them

329

might even foster critical thinking and reflection on

their actions. Educators and instructional/content

designers should be aware of this when designing

educational games: factors that help to support an

immersive experience not necessarily correlate with

factors that foster a situated learning experience. In

any case we highly recommend that further research

is needed to shed more light on this occurrence.

REFERENCES

Allison, C., Campbell, A., Davies, C. J., et al., “Growing

the use of VWs in education: an OpenSim

perspective”. Proc 2

nd

European Immersive Education

Summit, Gardner, M., Garnier, F., and Kloos, C. D.

Eds., pp. 1– 13, Paris, France.

Anasol, P. R., Callaghan, V., Gardner, M., and Alhaddad,

M. J. (2012). “End-user programming and

deconstrutionalism for cocreative laboratory activities

in a collaborative mixed-reality environment,” Proc

2

nd

European Immersive Education Summit, Gardner,

M., Garnier, F., and Kloos, C. D. Eds., pp. 171–182,

Paris, France.

Bazin, A. (1967) What Is Cinema? Essays. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Bredl, K., Groß, A., Hünniger, J., and Fleischer, J. (2012).

“The avatar as a knowledge worker? how immersive

3d virtual environments may foster knowledge

acquisition,” The Electronic Journal of Knowledge

Management, (10)1, 15–25.

Brown, E. and Cairns, P. (2004) ‘A Grounded

Investigation of Game Immersion’. CHI‘04 Extended

Abstracts on Human Factors and Computing Systems

(Vienna, April 2004), ACM Press, pp. 1297–1300.

Calleja, G. (2014) ‘Immersion in VWs’, in Grimshaw, M.

(eds.). The Oxford handbook of Virtuality, Oxford

University Press, New York.

Camilleri, V., de Freitas, S., Montebello, M., and

McDonagh-Smith, P. (2013). “A case study inside

VWs: use of analytics for immersive spaces” Proc 3

rd

International Conference on Learning Analytics and

Knowledge, pp. 230–234, Leuven: Belgium.

Chafer, J. and Childs, M. (2008). “The impact of the

characteristics of a virtual environment on

performance: concepts, constraints and complications”

Proc Researching Learning in Virtual Environments,

94–105, Open University, Milton Keynes:UK.

Childs, M. (2010). Learners’ experience of presence in

VWs [Ph.D. thesis], University of Warwick,

Coventry,UK.

Christopoulos, A. (2013). Higher education in VWs: the

use of Second Life and OpenSim for educational

practices (Master thesis, University of Bedfordshire,

Luton, UK). Retrieved from: http://uobrep.

openrepository.com/uobrep/handle/10547/291117.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2011). Research

Methods in Education, Routledge Taylor & Francis,

7

th

edition, London: UK.

de Freitas, S., Rebolledo-Mendez, G., Liarokapis, F.,

Magoulas, G, and Poulovassilis, A. (2010). “Learning

as immersive experiences: Using the four-dimensional

framework for designing and evaluating immersive

learning experiences in a VW,” The British Journal of

Educational Technology, 41(1), 69–85.

de Freitas, S., Rebolledo-Mendez, G., Liarokapis, F.,

Magoulas, G., and Poulovassilis, A. (2009).

“Developing an evaluation methodology for

immersive learning experiences in a VW,” Proc

Conference in Games and VWs for Serious

Applications, pp. 43–50, Coventry: UK.

Elliott, J. B., Gardner, M., and Alrashidi, M. (2012).

“Towards a framework for the design of mixed reality

immersive education spaces,” Proc 2

nd

European

Immersive Education Summit, Gardner, M., Garnier,

F., and Kloos, C. D. Eds., Paris, France.

Herrington, J., & Oliver, R. (2000). An instructional

design framework for authentic learning environments.

Educational Technology Research and Development,

48, 23-48.

Hockey, A., Esmail, F., Jimenez-Bescos, C., and Freer, P.

(2010). “Built Environment Education in the Era of

Virtual Learning,” Proc. W089 - Special Track 18

th

CIB World Building Congress, 200–217.

Jones, D. (2013) “An alternative (to) reality,”

Understanding Learning in VWs”, M. Childs and A.

Peachey, Eds., Human–Computer Interaction Series,

1–20, Springer, London: UK.

Levesque, J., and Lelievre, E. (2011). “Creation and

communication in virtual worlds: experimentations

with OpenSim,” Proc Virtual Reality International

Conference, Richir, S., and Shirai, A., Eds., 22–24,

Laval: France.

Nell, V (1988) Lost in A Book: The Psychology of

Reading for Pleasure. New Haven: Yale, University

Press.

Slater, M., and Wilbur, S. (1997). ‘A framework for

immersive virtual environments (FIVE): Speculations

on the role of presence in virtual environments’.

Steuer, J. (1992). “Defining virtual reality: dimensions

determining telepresence” Journal of Communication,

42(2), 73–93.

Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Qualitative

Research – Techniques and Procedures for

Developing Grounded Theory, second edition,

London, Sage Publications.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind Society: The Development

of Higher Mental Processes, Harvard University

Press, Cambridge, Mass:USA.

Witmer BG, Singer MJ (1998) Measuring presence in

virtual environments: A presence questionnaire.

Presence Teleoperators and Virtual Environments,

7:225-240.

Zhao, H., Sun, B., Wu, H. and Hu, X. (2010) “Study on

building a 3D interactive virtual learning environment

based on OpenSim platform” Proc International

Conference on Audio, Language and Image

Processing, pp. 1407–1411, Shanghai: China.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

330