Mobile Technology to Monitor Physical Activity and Wellbeing in

Daily Life

Objective and Subjective Experiences of Older Adults

Miriam Cabrita

1,2

, Monique Tabak

1,2

and Miriam Vollenbroek-Hutten

2

1

Roessingh Research and Development, Telemedicine group, Enschede, Netherlands

2

Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Science, Telemedicine group,

University of Twente, Enschede, Netherlands

Keywords: Wearables, Active Ageing; Positive Emotions.

Abstract: Older adults are not reaching the recommended guidelines for physical activity. There is growing evidence

that physical activity and positive emotions reinforce each other. However, the development of interventions

leveraging this knowledge faces several challenges, such as the limited knowledge on the assessment of

emotional wellbeing in daily life using technology. In this study, we investigate the experience of older adults

regarding the use of mobile technology to coach physical activity and monitor emotional wellbeing during

one month. Our results show that the participants became more aware of their daily physical activity and

perceived an added value in using the technology in daily life. However, only limited added-value was

perceived on monitoring positive emotions in daily life in the way we performed it. The most common

argument concerned repetitiveness of the questions being asked every day. Moreover, participants also

reported that they were not used to think about their emotions, what affected the way they answered the

questions regarding their emotional wellbeing. Our results suggest that, to ensure reliability of the data, it is

extremely important to hear the experience of the participants after performing studies in daily life.

1 INTRODUCTION

Lack of physical activity and prevalence of physical

inactive is a global problem. The World Health

Organization points out physical inactivity as the

fourth leading cause for global mortality (World

Health Organization 2009). Despite the overall

policies for promotion of physical activity and the

well-known benefits for physical and mental health,

older adults are still not active. In the literature, the

proportion of older adults reaching the recommended

guidelines ranges from 2 to 83%, depending on the

guidelines and assessment methods chosen (Sun et al.

2013). Mobile technology has already provided

promising results in promoting physical activity, yet

the older population shows low interest in using

activity trackers (Alley et al. 2016). One reason might

be that the market of physical activity trackers often

targets a young, active and healthy population. It is

therefore important to hear the experiences and

opinions of the older adults, when intending to

develop interventions to promote physical activity

using mobile technology.

One emerging line of research combines

promotion of healthy lifestyles with promotion of

emotional wellbeing. For example, adapting

Frederickson’s ‘upward spiral theory of lifestyle

change’ to the promotion of physical activity, being

physically active might enhance emotional wellbeing

and, in turn, higher experience of emotional

wellbeing might motivate people to be more engaged

and active (Fredrickson 2013). To be confirmed, this

theory might open new horizons on interventions

promoting physical activity and, furthermore,

combining physical and mental health.

Mobile technology allows innovative methods to

assess multiple parameters simultaneously. However,

there is limited knowledge on the assessment of

emotional wellbeing in daily life, especially using

mobile technology. Emotional wellbeing concerns

positive affective states, or positive emotions

(Fredrickson 2001; Lyubomirsky et al. 2005).

Experience sampling, also known as ecological

sampling, is a commonly used method in research to

assess emotions in daily life (Csikszentmihalyi &

Hunter 2003), and provides the means to assess

164

Cabrita, M., Tabak, M. and Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.

Mobile Technology to Monitor Physical Activity and Wellbeing in Daily Life - Objective and Subjective Experiences of Older Adults.

DOI: 10.5220/0006321101640171

In Proceedings of the 3rd Inter national Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2017), pages 164-171

ISBN: 978-989-758-251-6

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

positive emotions following the requirements

proposed by Kanning and colleagues (Kanning et al.

2013). Despite its value for research, it has been less

explored as a monitoring method, to be used over

longer periods of time and create awareness about the

own wellbeing.

In this study, we present the results of a one-

month daily life study that investigates objective and

subjective experiences of community-dwelling older

adults regarding physical activity promotion and

monitoring of positive emotions in daily life. This

work has two main objectives:

1 To investigate how older adults experience

promotion of physical activity in their daily life

using mobile technology;

2 To investigate how older adults experience

monitoring positive emotions in their daily life

using mobile technology;

As an exploratory study we also propose to

investigate the relation between physical activity and

experience of positive emotions per day.

This study is innovative as it provides older adults

with technology that is normally more appealing to

younger adults, and by investigating both objective

and subjective experience of using this technology in

daily life. This study focuses on the individual

experience, following each participant for the course

of one month with an interview at the end of this

period to elicit subjective experiences. The results of

this study will be used in the development of

technology-based interventions to promote physical

activity and emotional wellbeing among older adults.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants

Twenty-three older adults were recruited in the

PERSSILAA project (www.perssilaa.eu) and in

events related to promotion of healthy behaviours. All

who were interested received information letters via

post explaining the research in more detail and were

invited for an interview at the premises of the

participating institution. Twelve older adults (7

female) accepted to participate in the study.

Technology was explained by two researchers and the

participants had time to ask questions. Participants

were asked to use the technology at their own pace

during four weeks. This study adhered to the

guidelines set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki and

it was approved by the institutional review board at

the participating institution. All participants provided

written informed consent.

The average age of the participants was 69 years

old (range 65 – 78 years). Three participants lived

alone, 8 with someone else and 1 did not want to share

this information. This participant dropped out after 5

days due to data privacy concerns. Although

authorization was given to use the 5 days of data, we

decided to not include the data. According to the

frailty assessment from the Groningen Frailty

Indicator (GFI) (Steverink et al. 2001), 3 participants

suffered from decline, 7 were robust, and 2 were

inconclusive due to missing data. In particular, 2

participants evidenced some physical function

decline when assessed with the Short Form-36 Health

Survey (Ware 1993). Table 1 provides a global

overview of the demographics and health related

characteristics of the participants.

Table 1: Characteristics of the participants (n=11).

Characteristic N, range, (%)

Age (mean, range) 69, 65 - 78

Gender

Female

Male

6 (55%)

5 (45%)

Living Situation

Alone

With someone else

3 (27%)

8 (73%)

Education

Elementary School

High School

Vocational School

University

1 (9%)

3 (27%)

6 (55%)

1 (9%)

General Frailty (GFI)

Decline

Robust

Missing

3 (27%)

7 (64%)

1 (9%)

Physical Function (SF-36)

Decline

Robust

2 (18%)

9 (82%)

BMI (mean, range) 25.3 (17.4 - 36.1)

2.2 Measurements

Physical Activity. Physical activity was monitored

using a Fitbit Zip® step counter that can be worn in

the pocket to assess number of steps throughout the

day. Literature has shown that this step counter

provides a valid estimation of the number of steps in

both the laboratory (Case et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2014;

Kooiman et al. 2015; Nelson et al. 2016) and free-

living (Ferguson et al. 2015; Tully et al. 2014;

Kooiman et al. 2015) environments with accuracy

values ranging between 0.90 and 1 in both conditions.

Mobile Technology to Monitor Physical Activity and Wellbeing in Daily Life - Objective and Subjective Experiences of Older Adults

165

Feedback on physical activity was provided on the

device itself, and also on the screen of the mobile

phone, using the Activity Coach application. This

application is a re-design of the application developed

by Roessingh Research and Development and tested

with several clinical populations, such as cancer

survivors (Wolvers et al. 2015) and patients suffering

from chronic pulmonary obstructive disease (Tabak

et al. 2014). In the mobile phone, participants

received feedback on the number of steps at that

moment, number of steps at the current day per hour

and during the last week per day. Participants could

also see a representation of how far they were from

reaching the daily goal. The daily step goal was set to

7500 steps, following the research of Tudor-Locke

and colleagues (Tudor-Locke et al. 2011).

Participants were told that this goal could be changed

upon request.

Positive emotions. Emotional wellbeing was

operationalized by 6 discrete positive emotions.

Participants were asked at the end of every day (at

20:30) to which extent they experienced six discrete

positive emotions (joy, amusement, awe,

love/friendliness, interest and serenity) and to rate it

on a Likert scale from 1 (‘not at all’) to 7 (‘very

intense’). The positive emotions asked were taken

from the modified Differential Emotions Scale

(Fredrickson 2013). The emotions were chosen to

cover the full arousal, or activation, dimension.

Usability and feasibility. At the end of the 4-week

period, participants were invited for a semi-structured

interview to share their experience. The objective of

this interview was to obtain an extended evaluation of

the usability and feasibility of the system. Examples

of questions asked were “Which features of the

Activity Coach do you consider as the most

important?” and “Did you become more aware of

your wellbeing by answering the questions daily?”.

2.3 Data Analysis

The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed

verbatim. The transcripts were categorized in themes

and sub-themes using inductive thematic analysis

(Braun & Clarke 2006). An iterative process was

taken until eliciting the final codes.

Correlations between physical activity and

positive emotions are calculated with bivariate

correlation analysis. A composed variable of daily

positive emotions was created by summing the results

of the 6 emotions. Physical activity was

operationalized in 4 discrete variables retrieved

directly from the Fitbit classifications: number of

steps per day, and number of minutes per day spend

in each one of the following activity levels: inactive,

lightly active, moderate-to-very active.

3 RESULTS

Eleven older adults participated in the study on an

average of 27 days resulting on a total of 292 days of

data collected. The daily average of steps was slightly

above 6000 steps, with the daily averages among

participants varying from 2989 to 10572 steps per

day. Table 2 provides a summary of the combined

results from all participants.

3.1 Experience of Promotion of

Physical Activity in Daily Life

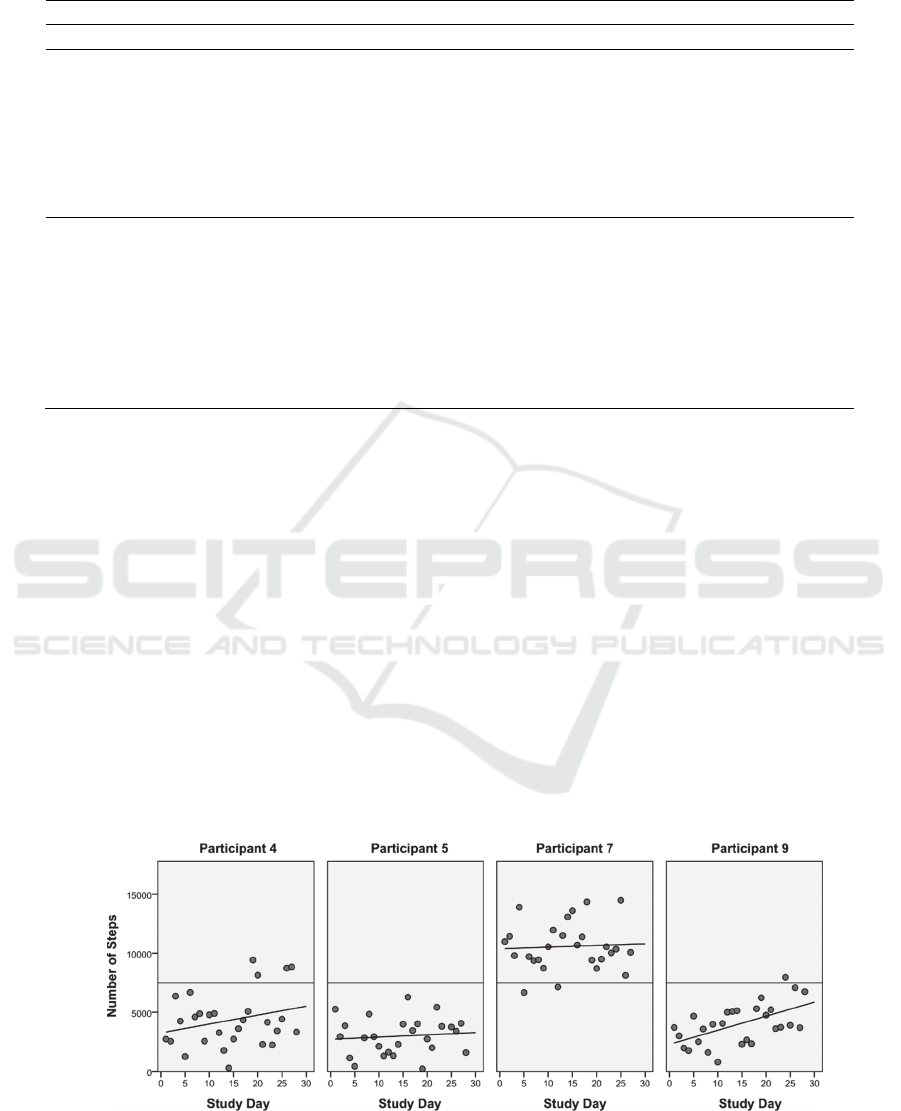

Figure 1 provides an overview of the number of steps

per day performed by four participants. Only 1

participant in the study consistently met the daily

goal, 5 participants almost never reached the daily

goal and the remaining 6 participants reached the goal

almost on half of the days. No subject asked to change

the goal during the study period. The participant who

met the goal every day said that he/she was not

interested in increasing the goal due to the

accomplishment feeling experienced by seeing that

the goal was achieved every day. When asked about

the difficulty of the step goal, 4 participants reported

that it was too high, as they could not reach the goal

in (almost) any day. Three participants found the goal

appropriate, as in challenging but achievable,

considering that it requires an extra effort to be

achieved, as “it comes not by itself”. One participant

found the goal very difficult in the beginning but it

motivated him/her to become more active, and at the

end of the 4 weeks it was actually easy to achieve.

Two participants found the goal easy or very easy.

Finally, 1 participant said that he/she did not look at

the goal during the 4 weeks. Most participants

reported that the Activity Coach helped them to

become more aware of their physical behavior and

helped them to become more active.

“In the beginning I found the daily goal very high,

but now it does not look much at all. If you walk 2

kilometers you are almost there. And then if you

walk a bit in the house you reach the goal.”

(Male, 66 yrs)

When comparing the measured average number of

steps of each participant with the sample average, 4

participants are substantially above the average, 2

slightly above (less than 500 steps difference) and 4

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

166

Table 2: Descriptive analysis of the parameters assessed regarding physical activity and emotional wellbeing.

Characteristic Mean (standard deviation), range

Study duration in days (N=292) 27 (1.5), 23 – 28

Physical Activity (N = 273)

Steps

Full sample

Variation between subjects

6316 (3688), 224 – 20158

2989 – 10572, (1554 – 5044), 224 – 20158

Distance (km) 4.51 (2.67), 0.15 – 15.51

Sedentary minutes per day 1269 (72), 1037 – 1440

Moderate-to-intense active minutes per day 29 (34), 0 – 215

Daily wellbeing (N = 272)

Joy 5.53 (0.79), 3 – 7

Awe 5.55 (0.77), 3 – 7

Interest 5.63 (0.72), 3 – 7

Serenity 5.64 (0.90), 2 – 7

Love / Friendliness 5.75 (0.84), 3 – 7

Amusement 5.68 (0.92), 3 – 7

Sum of positive emotions 33.76 (4.34), 19 – 42

participants are below the average. When asked about

how the participants perceive their physical activity

level compared to their peers, two participants

answered that they perceive themselves as more

active than average, whereas, in fact, their measured

physical activity is below average.

There are also divergences when looking at the

comparison between self-perceived and objectively

measured change in physical activity during the 4

weeks period. Three participants perceived

themselves as becoming more active while in fact this

did not happen, while 2 participants said they did not

become more active while that data actually shows

they did.

All participants were satisfied with the possibility

to see an overview of the number of steps per day and

per week. This overview helped participants

becoming more aware of their physical activity

encouraging them to become more active.

“It just motivates you, and I kind of like it to keep

track of what you’re doing and what you’re doing

per week and per day, yes I like it very much.”

(Female, 70) or “Yes, one time I was like ‘ehm, today

I had a little less, so tomorrow I should be moving a

little more’" (Female, 70)

Besides the functionalities currently available,

participants would like to see an overview of their

steps over longer periods of time (e.g. months or

years) and would like to also see the distance

performed on each day. Participants would also like

to see personalized recommendations on how to

achieve the desired physical activity level.

Figure 1: Variation of the number of steps per day for 4 participants. The coloured circles represent the number of steps taken

on that day, the black line, the trend on the number of steps during the study. The green line represents the goal set to 7500

steps per day.

Mobile Technology to Monitor Physical Activity and Wellbeing in Daily Life - Objective and Subjective Experiences of Older Adults

167

Nine participants reported that they see the added

value of using technology in daily life for monitoring

physical activity. One of the participants bought a

step counter for him/herself while participating in the

study. Two participants said that, although it was fun

to monitor physical activity, they would not do it in

everyday life. These were the most active

participants.

“I have to admit that, now that I have participated

in this study, it is very clear for me how important it

is to monitor physical activity.” (Female, 73)

3.2 Daily Monitoring of Positive

Emotions

From the small standard deviations of the ratings of

experience of positive emotions in Table 2, it is

visible that most of the participants use only 3 values

of the Likert’s scale providing a very small variability

during the study. The reliability of the scale of

positive emotions in this sample was acceptable

(Cronbach’s α = .93).

The opinions of the participants regarding

monitoring of emotional wellbeing varied notably.

Six participants considered that they became more

aware of their wellbeing by answering the questions.

“You really learn to realize the way you are and

the way you work, you start to think about these

things a little more, yes.” (Female, 70)

However, only 4 participants saw an added value

on this. Most participants were very critical about

answering the wellbeing-related questions. The most

referred remarks concerned the repetition of the

questions, i.e. every day the same questions, and the

fact that no feedback was provided.

“Ok but it is always the same question, then I

answer every time the same, 6, 6, 6, 6 and ok that

time a 7 because I was really happy, but nothing

else…” (Male, 78)

“I mean I would consider a 4 too little, that is not

correct. Then I have to choose among the other

numbers, I don’t stay at the 7, because that would be

idiotic, right? No, I wouldn’t do it!” (Female, 67)

Also, participants found it difficult to understand

how the emotions differ between each other.

“The questions are in fact almost the same. If you

are satisfied, than you are also happy more often,

this type of thing…” (Female, 72)

One subjected mentioned that he/she would like

to see the feedback on positive emotions linked to the

feedback on physical activity.

3.3 Relation Between Physical Activity

and Positive Emotions

The reports of the participants on the experience of

monitoring positive emotions in daily life, made us

question the reliability of the data collected and,

consequently, limit the analysis to correlation

analysis, only to grasp a feeling of the data. Table 4

provides the results of the bivariate relation between

distinct ways of operationalize physical activity (i.e.

steps, distance, and total number of minutes engaged

in sedentary, light intensity and moderate to high

intense physical activity) and positive emotions

(happiness, cheerful, curious, calm, friendly and

Table 3: Self-perception of physical activity (PA) level compared to peers and objectively measured, as well as self-perception

of change in physical activity during the 4 weeks of study and objectively measured. In grey shadow are represented the cases

when the subjective perception and the measured data coincide.

Participant

Self-perception of PA

compared to peers

a)

Objectively measured

PA compared to peers

b)

Self-perception

of change in PA

Objectively measured

change in PA

1 + + - +

2 + + + -

3 - - + -

4 + - + +

5 / - - /

6 + ++ - /

7 + ++ - /

8 + - - +

9 - - + -

10 + ++ + +

11 + ++ / /

a) + represents more active than peers, / corresponds to neutral or unclear statements and - corresponds to less active than

peers

b) ++ represents more active than peers and quite above the daily goal, + more active than peers but average below goal line,

- less active than peers

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

168

satisfied, and sum value). The number of steps per

day and the distance is significantly associated to the

daily ratings of curiosity/interest (p<0.05).

Furthermore, the number of sedentary minutes is

associated to the rating of friendliness (p<0.05).

4 DISCUSSION

In this study we compared the subjective and

objective experience of coaching physical activity

and monitoring positive emotions in daily life using

mobile technology. Older adults see an added value

on monitoring physical activity, but not so much in

monitoring wellbeing. Moreover, we investigated the

relation between physical activity and six discrete

positive emotions. Our results suggest that the

relation between physical activity and positive

emotions is not direct, suggesting that other factors

might act as moderators. However, due to the small

sample size and considering the criticism concerning

the assessment of positive emotions, these results

should be taken with caution and we highly

encourage further research. In the following sub-

sections, the results associated to each one of the

objectives are discussed in more detail.

4.1 Experience of Promotion of

Physical Activity in Daily Life

In general, the participants were very satisfied with

the opportunity to monitor physical activity in daily

life and, in particular, with the tracker chosen. This

physical activity tracker is discrete, can be worn in the

pocket, has long battery duration and is simple. This

fact suggests that, although older adults are often not

the target population of the market of physical

trackers, after a small nudge to start using the

technology, they actually perceive an added value.

The average number of steps of the full sample

was approximately 6300 steps/day, with large

individual differences. In the present moment there is

no commonly accepted guideline for the number of

steps older adults should take per day. Literature

elsewhere reports similar ranges of steps with healthy

older adults ranging from 2000 to 9000 steps/day and

special populations 1200 to 8800 steps/day (Tudor-

Locke et al. 2011). It is therefore not surprising, that

some participants experienced the goal of 7500

steps/day as difficult, while others reached it with no

difficulty every day. This large variability in the daily

number of steps emphasizes the need for tailored

interventions with goals set specifically to each

individual. A possible approach to automatically

goal-setting is provided by (Cabrita et al. 2014). The

Goal-Setting theory suggests that, to be motivating,

goals must be challenging but achievable (Locke &

Latham 2002). This is clearly seen in the subjective

experience reported by the participants in the

interview. Those who were already very active, and

constantly above the daily goal, reported limited

added value from the system; on the contrary, those

who started below the goal, but close to it, mentioned

that the system helped to make them more aware of

their lack of physical activity and motivated them to

become more active. Similar results are presented by

(Eisenhauer et al. 2016).

During the four weeks of study, several technical

issues were reported, on the connectivity between the

step counter and the smartphone. Similar technical

problems are also reported in literature (Harrison et

al. 2014). Despite these issues, the participants

reported a positive experience, perceived the

Table 4: Bivariate analysis (Spearman 2-tailed) between several measures of physical activity and positive emotions.

Joy Awe Interest Serenity Love Amusement

Sum

Positive

Emotions

steps .056 .099 .141* -.053 -.099 .025 .020

distance .049 .095 .138* -.046 -.090 .028 .021

#minutes inactive .000 -.056 -.021 .093 .152* .014 .045

#minutes lightly

active

-.001 .041 -.010 -.071 -.111 -.001 -.035

#minutes moderate-

to-active

-.010 .017 .057 -.072 -.119 -.035 -.052

*p<0.05.

Mobile Technology to Monitor Physical Activity and Wellbeing in Daily Life - Objective and Subjective Experiences of Older Adults

169

technology as useful, and were comfortable using it.

Furthermore, it is difficult to distinguish between

inactive time and not worn time. This is particularly

difficult in the evenings, as it might be that older

adults stop carrying the step counter but keep doing

their normal activities.

4.2 Daily Monitoring of Emotional

Wellbeing

The opinions about monitoring emotional wellbeing

diverged. While part of the participants became more

aware about their wellbeing, only a few perceived an

added value. The strongest criticism was that

participants did not receive any feedback on their

answers. Some participants also referred that they

were not used to reflect on their emotions and do not

feel comfortable doing so. Participants perceived

wellbeing, or mental health, as something too

personal to provide information about to a machine.

This is perceived differently than information related

to physical health, showing the stigma might still be

present when talking about mental health.

Regarding the assessment method, participants

perceived the questions as too repetitive. We suggest

that, while experience sampling is a promising

method to assess emotions, attention should be given

when designing the questions. For example, variation

in the phrasing should be considered to avoid

unreflective answers.

Further research should be performed on the

assessment of emotional wellbeing in daily life. One

can think of strategies as facial recognition or text

mining from the data in social media; however, these

methods do not request reflection from the person

being assessed, as initially desired in this study.

Nevertheless, predictive models of daily emotions are

currently being investigated and can open room for

interventions in daily life, yet with limited confidence

in positive results (Asselbergs et al. 2016).

4.3 Relation Between Physical Activity

and Positive Emotions

Our study follows the 3 recommendations of the

Kanning and colleagues for within-subject analysis of

physical activity and affective states: objective

assessment of physical activity, the importance of real

time assessment, affective states measured

electronically (Kanning et al. 2013). Despite

following these recommendations, we were not able

to investigate the dynamics between positive

emotions and physical activity, as initially desired.

Based on the interviews performed after the study, we

considered that the answers given to the daily ratings

of positive emotions were not reliable. In any case,

our preliminary analysis suggests that there is some

evidence to confirm a relation between positive

emotions and physical activity, dependent on the

operationalization of the outcome. We recommend

further research investigating the context of the

activities. Another suggestion is to perform studies

for longer periods of time and extract only the data

points in which the experience of positive emotions

deviates from the mode value.

5 CONCLUSION

Our study suggests that older adults are willing to

monitor their physical activity in daily life and that

the technology helps them becoming more aware of

their current activity level. On the contrary, older

adults perceive limited added value of monitoring

emotional wellbeing in daily life – in this study

operationalized as experience of positive emotions –

mostly due to the repetitiveness of the questions. The

interviews performed with the participants at the end

of the study revealed low reliability on the data

collected on the wellbeing. For this reason, a

thorough analysis on the relation between physical

activity and positive emotions was not performed.

Further research needs to be performed in the

mobile assessment of emotional wellbeing before

being able to look at the relations with other factors.

The interviews performed after using technology

were extremely important to let us make sense of the

data collected. We would like to alert researchers

using mobile assessment of emotions to question the

reliability of their data when repeating the same

questions for a long period of time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work presented in this paper is being carried out

within the PERSSILAA project and funded by the

European Union 7th Framework Programme under

Grant FP7-ICT-610359. The authors would like to

thank Jandia Melenk and Nada El Meshawy for their

support conducting the interviews.

REFERENCES

Alley, S. et al., 2016. Interest and preferences for using

advanced physical activity tracking devices: results of a

national cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open, 6(7),

p.e011243. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/

bmjopen-2016-011243.

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

170

Asselbergs, J. et al., 2016. Mobile Phone-Based

Unobtrusive Ecological Momentary Assessment of

Day-to-Day Mood: An Explorative Study. Journal of

Medical Internet Research, 18(3), p.e72. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5505.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in

psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology,

3(May 2015), pp.77–101.

Cabrita, M. et al., 2014. Automated Personalized Goal-

setting in an Activity Coaching Application. In

Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on

Sensor Networks. SCITEPRESS - Science and and

Technology Publications, pp. 389–396. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.5220/0004878703890396.

Case, M.A. et al., 2015. Accuracy of smartphone

applications and wearable devices for tracking physical

activity data. Jama, 313(6), pp.625–626. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.17841.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. & Hunter, J., 2003. Happiness in

everyday life: The uses of experience sampling.

Journal of Happiness Studies, 4(January), pp.185–199.

Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1024409732742.

Eisenhauer, C.M. et al., 2016. Acceptability of mHealth

Technology for Self-Monitoring Eating and Activity

among Rural Men. Public health nursing. Available at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27757986.

Ferguson, T. et al., 2015. The validity of consumer-level,

activity monitors in healthy adults worn in free-living

conditions: a cross-sectional study. The international

journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity,

12, p.42. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/

s12966-015-0201-9.

Fredrickson, B.L., 2013. Positive Emotions Broaden and

Build. In P. Devine & A. Plant, eds. Advances in

Experimental Social Psychology. Burlington:

Academic Press, pp. 1–53.

Fredrickson, B.L., 2001. The role of positive emotions in

positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of

positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3),

pp.218–226.

Harrison, D. et al., 2014. Tracking physical activity:

problems related to running longitudinal studies with

commercial devices. Proceedings of the 2014 ACM

International Joint Conference on Pervasive and

Ubiquitous Computing Adjunct Publication - UbiComp

’14 Adjunct, pp.699–702. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2638728.2641320.

Kanning, M.K., Ebner-Priemer, U.W. & Schlicht, W.M.,

2013. How to Investigate Within-Subject Associations

between Physical Activity and Momentary Affective

States in Everyday Life: A Position Statement Based on

a Literature Overview. Frontiers in psychology,

4(April), p.187. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389

/fpsyg.2013.00187.

Kooiman, T.J.M. et al., 2015. Reliability and validity of ten

consumer activity trackers. BMC sports science,

medicine and rehabilitation, 7, p.24. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13102-015-0018-5.

Lee, J.M., Kim, Y. & Welk, G.J., 2014. Validity of

consumer-based physical activity monitors. Medicine

and Science in Sports and Exercise, 46(9), pp.1840–

1848.

Locke, E. a. & Latham, G.P., 2002. Building a practically

useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-

year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), pp.705–

717. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-

066X.57.9.705.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L. & Diener, E., 2005. The benefits

of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to

success? Psychological bulletin, 131(6), pp.803–55.

Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-290.131

.6.803.

Nelson, M.B. et al., 2016. Validity of Consumer-Based

Physical Activity Monitors for Specific Activity Types.

Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, (March).

Steverink, N. et al., 2001. Measuring frailty: developing

and testing the GFI (Groningen Frailty Indicator).

Gerontologist, 41, p.236.

Sun, F., Norman, I.J. & While, A.E., 2013. Physical activity

in older people: a systematic review. BMC public

health, 13(1), p.449. Available at: http://www

.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/449.

Tabak, M., op den Akker, H. & Hermens, H., 2014.

Motivational cues as real-time feedback for changing

daily activity behavior of patients with COPD. Patient

education and counseling, 94(3), pp.372–8. Available

at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.014.

Tudor-Locke, C. et al., 2011. How many steps/day are

enough? For older adults and special populations. The

international journal of behavioral nutrition and

physical activity, 8(1), p.80. Available at:

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/80.

Tully, M.A. et al., 2014. The validation of Fibit ZipTM

physical activity monitor as a measure of free-living

physical activity. BMC Res Notes, 7, p.952. Available

at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-952.

Ware, J.E., 1993. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and

interpretation guide, Boston, MA: The Health Institute,

The New England Medical Center.

Wolvers, M. et al., 2015. Effectiveness, Mediators, and

Effect Predictors of Internet Interventions for Chronic

Cancer-Related Fatigue: The Design and an Analysis

Plan of a 3-Armed Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR

Research Protocols, 4(2), p.e77. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/resprot.4363.

World Health Organization, 2009. Global Health Risks:

Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected

major risks. Bulletin of the World Health Organization,

87, pp.646–646. Available at: http://www.who.int

/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GlobalHealthRisks

_report_full.pdf.

Mobile Technology to Monitor Physical Activity and Wellbeing in Daily Life - Objective and Subjective Experiences of Older Adults

171