Land Use Planning for Sustainable Development of Coastal Regions

Areti Kotsoni

1

, Despina Dimelli

1

and Lemonia Ragia

2

1

School of Architecture, Technical University of Crete, Chania, Greece

2

School of Environmental Engineering, Technical University of Crete, Greece

Keywords: Coastal Erosion, Land Use, Urban Planning, Legislation.

Abstract: The current paper will focus on the coastal zone of Georgioupoli and its vulnerability as a result of the lack

of spatial planning. The case study is selected because it concentrates the characteristics of a typical coastal

touristic zone, which faces rapid intense unplanned touristic expansion. The examined zone has been

diachronically influenced by the liberalization of construction regulations, an unqualified private sector

emerged, hastily developing construction mostly without government oversight and without building

permits. We present a concept for planning sustainable development in coastal regions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Today’s coastal regions face intense problems

caused by the rapid urbanization, coastal erosion, sea

level rise, global warming and climate change.

These factors have a huge impact on coastal

communities. Especially in Greece with a coastline

length of 17400km and with many cities and

residential areas at the coastal regions the above

factors play an important role. The biggest island of

Greece is Crete which is predominantly based on

services on tourism and agriculture. Since 1970

Crete became a popular tourist attraction, it has more

than 2.000.000 tourists every year and this number is

increasing.

The massive influxes of tourists have pressed the

coastal regions with nice beach to create big tourist

developments. Hotels, marinas, roads, restaurants,

facilities for recreation and sport activities are some

of them. These results in great pressure mainly on

resources and on the marine ecosystems. Natural

habitats like of the seagrass meadow have been

removed to create open beach, other tourist

developments have been built directly next and on

the beaches. Careless constructions and resorts have

destroyed the beauty of the environment.

Tourism is a crucial aspect of the Greek

economy given the pleasant climate and sea

conditions which contribute to Greece’s overall

popularity as a tourist destination. In the Greek

coastal zone, there are major conflicts between the

demand for tourism on the one hand, and coastal

preservation on the other. The Greek coastal zones

face problems with delineation and definition of

public land cause significant uncertainties among

land owners regarding where the public domain

ends. For the protection of the coastal areas it is

important for Greece to conduct an evaluation of

planning and legislative tools in relation to these

zones.

One of the most significant problems is the

coastal erosion. It takes place through strong winds

and high waves and storm conditions and results in

loss of land and beach. One can observe at the

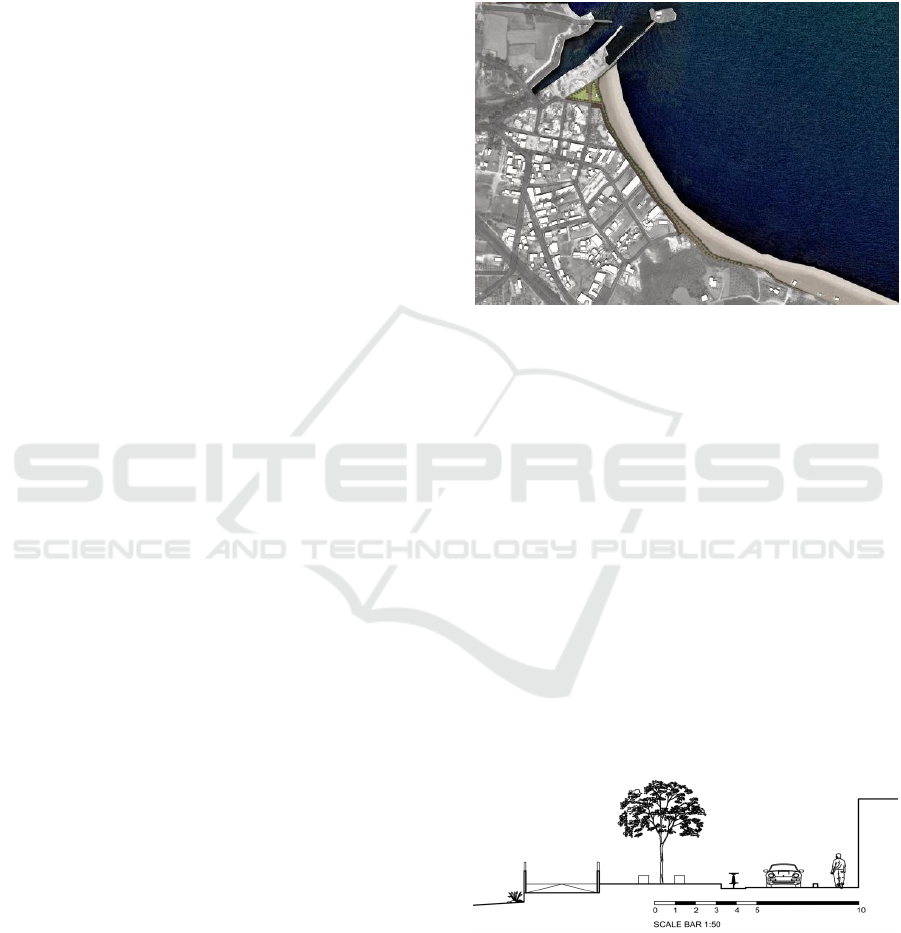

satellite images Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 the coastal erosion

at one coastal area in Crete, name Georgioupoli. The

first image is taken in 2003 and the second one in

2016. The sandy coast almost disappeared in the

second one. As one can see there are more buildings

in the second image and a road is constructed

between the residential part of the region and the

coast. Using GIS technologies it is found that the

length of the beach is 400m and the average width

40m which makes 16.000sqm loss of sandy beach. It

is estimated a loss of economic value 10€ per sqm

per day in Greek beaches that means 160.000€ per

day for such a small village like Georgioupoli in

Crete (Synolakis, 2013).

Human intervention is a major cause for coastal

erosion (Hsu et al., 2007). The construction of

different types of hard structures including seawalls,

breakwaters and roads are a major factor for coastal

erosion and beach loss. A main method for

protecting the coastline is beach nourishment which

290

Kotsoni, A., Dimelli, D. and Ragia, L.

Land Use Planning for Sustainable Development of Coastal Regions.

DOI: 10.5220/0006370802900294

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management (GISTAM 2017), pages 290-294

ISBN: 978-989-758-252-3

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

is a soft engineering solution (Phillips and Jones

2006).

Figure 1: The coast of the satellite image in 2003.

Figure 2: The coast of the satellite image in 2016.

In our approach we discuss the land use planning

and control laws for a sustainable development of

coastal regions for tourists. The current paper will

focus on the coastal zone of Georgioupoli and its

vulnerability as a result of the lack of spatial

planning. The case study is selected because it

concentrates the characteristics of a typical coastal

touristic zone, which faces rapid intense unplanned

touristic expansion. The examined zone has been

diachronically influenced by the liberalization of

construction regulations, an unqualified private

sector emerged, hastily developing construction

mostly without government oversight and without

building permits.

There are some main laws for constructions at

Greek beaches: a) The leasing of seashores and

beaches is allowed for works related to trade,

industry, land and sea transportation, or “other

purposes serving the public good”, b) beach zone 50

m wide, c) Access roads to the beach of minimum

width 10 m., means: expropriations of land

properties, d) fences are prohibited in a zone of 500

m from the beach in areas not covered by urban

plan. Exceptions: when agricultural fields have to be

protected, and e) “Light”, non permanent

constructions are allowed in the seashore zone,

meant to serve public recreation (tents, open bars

etc.) (Lalenis, 2014).

However there is a need for more detailed and

strict regulations for building a construction. The

current paper will propose ways for the problems of

coastal erosion and beach loss. It will propose a

concept for deepening the existing urban plan with

the use of light structures and creating detailed

constrains for the coastal areas.

2 LEGAL ASPECTS AND THEIR

EFFECTS ON THE AREA

The Greek legislation for coastal areas began in

1837 when an early law dealing with the Greek

public domain defined the “seashore” area as public

property. Decades later, in 1940, the country’s first

Coastal Law tried to protect the public domain status

of the coastal zone. This law added definitions for

“old seashore” and “beach” as additional elements of

the Greek coastal zone and applied a setback zone of

30 meters from the seashore in which construction

was prohibited outside of existing older settlements.

A main characteristic of this was that there is no

reference to the protection of coastal areas from an

environmental perspective. In 1998, that the Greek

Council of State has supported arguments that the

coast is a vulnerable ecosystem and should be

protected from intensive forms of development. The

1999 assessment report of the European

Environment Agency indicated a continuing

degradation of conditions in the coastal zones of

Europe as regards both the coasts themselves and the

quality of coastal water. In 2001, Greece’s enacted a

new Coastal Law which prioritized the protection of

the coastal zone as a public good, an environmental

asset and an economic good.

Land Use Planning for Sustainable Development of Coastal Regions

291

This law defined the beach as a zone adjacent to

the seashore, with a width of “up to 50metres”. This

zone is a buffer zone between land and sea and, like

the seashore, is included within the Greek public

domain. It is usually defined in spatial plans of

coastal settlements and rural areas as “open space”,

but may be used for roads, pedestrian and bicycle

routes. But there is no requirement that the beach is

defined and in many cases, it is not.

This law restricts development on the coastal

zone and beyond but it also provides many

exceptions to these restrictions in order to encourage

the tourism potential of the coast. Today the primary

issue is extensive illegal development in restricted

areas and a lack of political will to take action

against such development. The most recent law

(4178/2013) nullifies any previous laws which

allowed for legalization, though still provides

exceptions for types of development which may be

legalized. As was the case in 1983, illegal

development on public land, the beach, or seashore

may not be legalized and must be demolished. In

2014, Greece adopted a new procedure for

delineation of the coast based on the interpretation

of aerial photographs. Today coastal zones are

further threatened by the effects of climate change,

in particular rising sea levels, changes in storm

frequency and strength, and increased coastal

erosion and flooding.

Only light construction associated with seasonal

tourist and recreation facilities (open playgrounds,

kiosks, mobile beach bars and refreshment areas)

may be erected on the seashore and beach. The

process for their establishment includes an

application from business operators to the relevant

Municipality. The municipalities set the cost and the

revenue generated through the process is an

important component of their budgets. Still many

business owners violate these regulations. Access to

the sea is obstructed in many areas often by

approved private uses such as hotels and businesses.

The lack of controlling mechanisms combined

with loose policies has today made Planning of the

examined area ineffective. Although restrictions for

uses and buildings permits exist these are rarely

followed. The accessibility to the beach is mainly

served by cars that causes traffic congestion during

the summer period. The tourism infrastructures are

closer than the allowed distance to the beach and the

materials used for the creation of roads have

degraded the environment. All the above have led to

an area with a limited coast, with a limited access

that is mainly covered by seasonal facilities

accessible mainly to the clients of the area hotels.

3 REDISIGNING THE AREA

WITH SUSTAINABLE

PRINCIPLES

The design proposal of the present study for the

coastal zone of Georgioupoli aims at re-designing

the zoning of the beach, based on the legal

framework described above, in order to protect it

from anthropogenic and other impacts. We propose

the following concept:

1. Human intervention must be prohibited at any

case. There must be control using aerial or

satellite images to keep up with all the changes.

2. Offshore beach nourishment can restore the

beaches and protect them from erosion. There

are different methods for beach nourishment

(Dean, 2003) but for not so long beaches less

than 1km length sand can be located without

creating any problems.

3. Planted trees and natural vegetation will not

only provide a beautiful image of the scene but

provide a physical barrier against wind and

coastal erosion.

4. It is essential to remove the cars from the

coastal zone that means to avoid roads, even if

they are not intensively used. Free public access

towards the coastal zone is important by

planning what encourages the best possible

access to the beach.

5. Decongestion of the beach zone from traffic in

particular form public transport, as well as

encouraging and rewarding the use of

alternative modes of transportation, such as

bicycling and walking, is considered crucial.

Thereupon, the preservation of an one-way, 3.5

meter wide traffic axis is recommended for

bicycles, aiming to encourage safer, more

responsible driving, and potentially reduce

traffic flow (traffic calming).

6. Seawall constructions should not be allowed. It

is already discussed that seawalls increase

erosion and destroy the beach (Basco 1999)

7. The construction of the roads to the beach must

be made by other material then asphalt. The

removal of asphalt road and its replacement by

sidewalks by paved floor allows the

development of a variety of other uses such as

the bicycle, pedestrians, playgrounds and

staging areas. Therefore a well-designed coastal

zone with public uses can attract not only

tourism but also the area’s residents.

8. Beach access with “vertical” or perpendicular

lines. Public authorities have the right to

GISTAM 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management

292

develop public access to the beach and we

recommend a road infrastructure to the beach

that along the beach. Moreover, access to the

beach is intended to be made easier and more

pleasant, so that more visitors are attracted and

at the same time balance between ecological

integrity with beach access is achieved.

9. Aesthetic parameters provide an added value to

the coastal regions especially when they are

used for swimming and touristic purposes.

There must be some criteria for the color used

for the buildings and other constructions, for

construction’s material or roof types.

10. An important principle in our concept of

sustainable development of the coastal regions

is the idea try to ‘build with nature material’.

Standards for the restoration of older structures

could serve as a supplementary means of

improving the appearance of existing structures.

Laws, policies and regulations should focus on

coastal management issues, with a view to improve

the integration of a full range of problems. It is

important for regional and urban planning to add

specific reference for the protection the coastline to

their respective constitutions. Such strategies

provide integrated policies for coastal zone

management, which can complement the relevant

existing legislation.

It is also important to limit the use of the coastal

uses that are inherently linked to the sea and to limit

uses that provide economic or social benefit.

Policies should focus on procedures that include

time limits for temporary structures and rules for

renewal. Rules should be also geared towards

reducing expectations of temporary structures

becoming permanent.

3.1 Case Study

To demonstrate the realization of our concept we use

the coastal region at the village of Georgioupoli at

North Part of Crete.

First of all the possible solution of the erosion

problem would be beach nourishment. This is a soft

engineering solution to protect both the beach and

tourism infrastructure (Fig. 3).

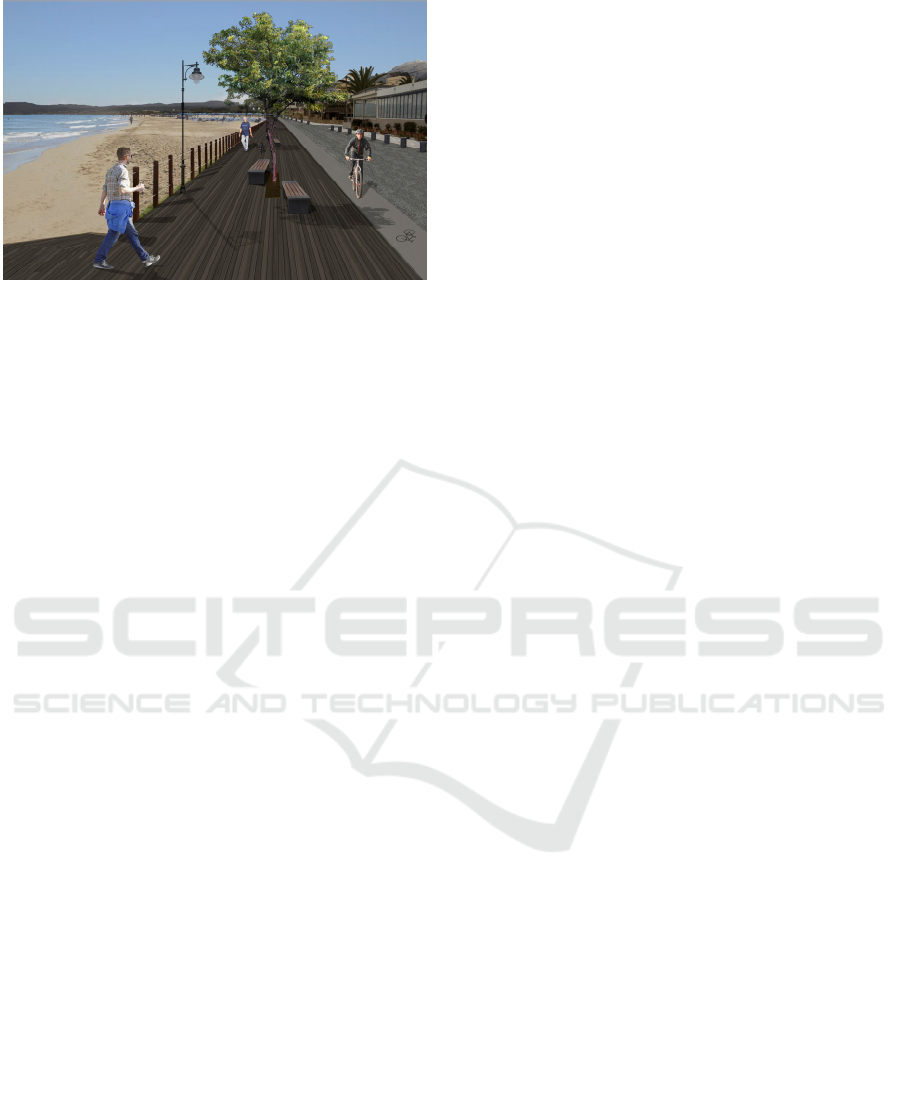

Then we propose the existing road will be

replaced of natural stone, such as sandstone slabs, a

material that does not pollute the environment, and

additionally has the required strength. We abolish

one lane and the final width of the road will be 3.5

meters. On the side of the street to the sea a bicycle

lane is designed, with a total width of 1.2 meters,

while on the opposite site, in front of the facades of

the existing buildings, an oblate pavement, with a

total width of 2 meters is constructed. The pavement

will be at the same level with the street and will be

separated using short stanchions (Fig. 4). Today in

the existing situation, a two-way, 7 meter wide (on

average) street existed parallel to the beach.

Figure 3: The coast with the beach nourishment and the

green area at the end of the beach.

Continually a wooden deck will be designed next

to the road 1 meter above the level of the sand which

is a light construction protecting the sand from other

material from the road. It can be enhanced with

vegetation such as trees both to protect the coast and

for shading (Fig. 5). Moreover, for practical and

aesthetic reasons benches will be placed as stopping

areas, as well as ramps for smooth ascent and

descent to, and from the road and to the beach.

At the end of the construction, a green area will

be designed, together with the construction of an

outdoor gym and a playground (Fig. 3). In this case

more buildings are not suggested. The green area is

a natural continuation of the trees along the

pavement and the combination of blue and green

creates a peaceful and satisfied atmosphere.

Figure 4: Section part of the coast with vegetation and

roads.

Land Use Planning for Sustainable Development of Coastal Regions

293

Figure 5: The new lanes according to the proposal.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Greece should undertake a comprehensive

assessment of not only current, but also projected,

urban areas to determine the desired urban form and

its interactions with the coastal zone. Such an

assessment will allow for development of specific

policies which match the desired outcomes.

It is essential for planning to encourage coastal

regions development according to the principles of

sustainable development.

A small scale design such as the one described

above can be proved beneficial both for the human

and for the environment. The re-design proposal

focused not only on sustainable but also in touristic

development. Equally important to the above is the

use of natural materials that do not harm the

environment, as in this case the replacement of

asphalt with natural stone and wood. Especially

when the delineation process of the coast is not

necessary the design of light structures with the use

of materials which do not harm the environment and

the creation of natural vegetation filters is required.

REFERENCES

Davis, Jr. R. & Fitzgerald, D. (2009). Beaches and coasts,

John Wiley & Sons.

Dean, R. G. (2003). Beach nourishment: theory and

practice. Vol. 18. World Scientific Publishing Co Inc,

2003.

European Environment Agency (2006). The changing

faces of Europe's coastal areas. Office for Official

Publ. of

Hsu, T.W., Tsung-Y. L., and I-Fan Tseng (2007). Human

impact on coastal erosion in Taiwan. Journal of

Coastal Research (2007): 961-973.

Lalenis, K. (2014). Integrated Coastal Zone Management

in Greece: the legislative framework and its influence

on policy making and implementation. In 1

st

Conference Cross-Border Cooperation on ICZM,

Alexandroupolis, Greece, February 18-24.

Phillips, M. R., and Jones, A. L. (2006). Erosion and

tourism infrastructure in the coastal zone: Problems,

consequences and management. Tourism

Management 27.3 (2006): 517-524.

Portman M. E. (2016). Environmental Planning for Ocean

and Coasts: Methods, Tools and Technologies.

Swinger. Switzerland

Olshansky, R. B., Kartez, J.D. (1998) Managing land use

to build resilience. In: Burby RJ (ed) Cooperating with

nature: confronting natural hazards with land-use

planning for sustainable communities. Joseph Henry

Press, Washington, pp 167–201.

Synolakis C. (2013): http://www.iefimerida.gr/

news/11557/ πώς-χάνονται-20-στρέμματα-παραλίας-

και-έσοδα-δύο-εκατ-ευρώ-κάθε-χρόνο-στα-χανιά

United Nations (UN) (2010). Local governments and

disaster risk reduction: good practices and lessons

learned. UNISDR, Geneva

GISTAM 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management

294