Factors Influencing the Participation of Information Security

Professionals in Electronic Communities of Practice

Vivek Agrawal, Pankaj Wasnik and Einar Arthur Snekkenes

Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Gjøvik, Norway

Keywords:

Electronic Communities of Practice, Information Security, Knowledge Sharing.

Abstract:

The purpose of this study is to contribute to a better understanding of the current status of the participation

of the information security professionals (ISPs) in the electronic communities of practice (eCoP) in the infor-

mation security (IS) domain in Norway. An online survey is conducted with 56 ISPs working in Norway to

investigate this issue. This study used the logistic regression as a statistical technique to formulate the results

and findings. The probability of an ISP being a user of eCoP is tested with demographic data, nature of the job,

and the knowledge sharing preference. Furthermore, the determinants of the knowledge sharing theories, i.e.,

the theory of planned behavior, the motivation theory, and perceived trust theory are used to test our statistical

model. The findings of this study are useful to get the initial insight into the determinants that influence the

participation of ISPs in eCoP in Norway.

1 INTRODUCTION

The ISPs working in different organizations in Nor-

way often face many of the same problems and de-

sign similar solutions. ISPs also collect and apply the

same knowledge to design their solutions. However, it

is inefficient if they do it so largely on their own (Fenz

et al., 2011). Therefore, proper sharing and reuse of

knowledge among the ISPs can improve the quality

of their work (Von Krogh, 1998). The involvement of

information security practitioners and learning is an

important cog in the wheel of knowledge translation.

The knowledge available on the information security

guidelines and journals is inadequate to solve the day-

to-day problems faced by ISPs in their job. An evolv-

ing body of research suggests that communities of

practice can be effective in engaging the profession-

als and enable the sharing of knowledge among them.

The members discuss issues, and learn from others’

experience to solve the challenges in their job. The

nature of the learning that evolves from these com-

munities is collaborative, i.e., the collective knowl-

edge of the community is greater than any individual

knowledge (Johnson, 2001), (Liedtka, 1999).

With the advancement in information and com-

munication technologies, communities of practice

adopted the possibility of virtual communication

among the members of the community (Ho et al.,

2010). Modern information technologies can extend

the boundaries and reach of these communities by

providing an electronic platform to share knowledge

in the community. The electronic communities of

practice (eCoP) can establish collaboration across ge-

ographical locations and time zones. The adoption

of eCoP is not restricted to any particular commu-

nity or domain. The application of eCoP is spread

across health care (Ho et al., 2010), finance sec-

tor (Ardichvili et al., 2002), banking & Information

Technology (Probst and Borzillo, 2008). However,

it is not explicitly evident whether eCoP is popular

among the ISPs in Norway. We believe that shar-

ing of knowledge among the ISPs improve IS in Nor-

way. Therefore, we investigate the following research

question in this study:

RQ1: What are the factors affecting the partici-

pation of information security professionals in elec-

tronic communities of practice in Norway?

This study contributes towards the understanding

of the various factors that influence the participation

of ISPs in eCoP in Norway. We are interested in in-

vestigating this issue because we want to establish an

open electronic community of practice in IS for the

ISPs. Therefore, it is imperative for us to learn the

present status of participation of ISPs in eCoP as there

is a lack of literature.

An online survey is conducted with the members

of ISF, Norway. The participants of this survey are

also the target audience (in the form of members) of

Agrawal V., Wasnik P. and Snekkenes E.

Factors Influencing the Participation of Information Security Professionals in Electronic Communities of Practice.

DOI: 10.5220/0006498500500060

In Proceedings of the 9th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (KMIS 2017), pages 50-60

ISBN: 978-989-758-273-8

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

the electronic community that we are interested in es-

tablishing. We collected the responses from the ISPs

to understand the nature of their job, the source they

use to collect essential information for their task, and

the challenges they face in obtaining such informa-

tion. Furthermore, we also collected their knowledge

sharing preferences in eCoP based on the factors de-

rived from the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen,

1991), motivation theory (Frey and Osterloh, 2001),

and perceived trust (Usoro et al., 2007). The findings

of this study act as a starting point to get an initial in-

sight into the popularity of eCoP among ISPs in Nor-

way.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: In

section 2, the existing literature is used to describe the

concepts and knowledge sharing in eCoP. In section

3, the research approach of the study is explained. In

section 4, the findings of the study is explained with

the help of survey responses. Finally, the paper ends

with a discussion of the results, stating the implication

of the findings, limitation of the study and expected

future work, and conclusion.

2 RELATED WORK AND

BACKGROUND KNOWLEDGE

This section presents an overview of the difference

between traditional CoP and eCoP followed by the

studies covering the knowledge sharing activities in

eCop.

2.1 Traditional vs Electronic

Communities of Practice

The term ’communities of practice’ (CoP) is intro-

duced by Wenger et al. in 1998 (Wenger, 1998). The

basic concept of CoP is presented by Lave & Wanger

(Lave and Wenger, 1991), and by Brown & Duguid

(Brown and Duguid, 1991) in 1991. According to

Wenger (Wenger et al., 2002), ”Groups of people who

share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about

a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and exper-

tise in this area by interacting on an ongoing ba-

sis” A CoP mainly consists of three fundamental ele-

ments: a) Domain creates common ground and sense

of common identity. A well-defined domain enables

the community to understand its purpose and value

to the members and stakeholders associated with the

community, b) Community creates the bond among

the members that enable the learning among them. A

strong community can be developed when the mem-

bers have mutual respect and trust among them. A

strong community also encourages healthy interac-

tions and discussion, c) Practice is the specific knowl-

edge the community develops, shares, and maintains.

A practice can be set of ideas, tools, information that

the community members share (Wenger et al., 2002).

A CoP can exist in offline (also known as tra-

ditional) or electronic or both the forms. The of-

fline form uses face to face meeting, round table dis-

cussion, whereas the electronic form uses networked

technology, mainly the Internet, to establish collabo-

ration among the members across the world. The idea

of having an electronic platform for the traditional

communities of practice is supported in the stud-

ies (Mathwick et al., 2008), (Wiertz and de Ruyter,

2007). The traditional communities rely heavily

on the location and have membership according to

norms. The electronic communities are organized

around an activity, idea or task rather than location

(Johnson, 2001). The electronic nature of the commu-

nity provides the opportunities to facilitate communi-

cation among the members from different geographic

locations and time zones. The electronic CoPs com-

bine both online activities and face to face meetings

to enhance the interaction process.

2.2 Knowledge in Electronic

Communities

According to the work of (Wasko and Faraj, 2000),

there are three perspectives of knowledge on the def-

initions of knowledge, i.e., Knowledge as object,

knowledge embedded in individuals, and knowledge

embedded in a community. In this study, we focused

on the third perspective, i.e., knowledge embedded in

a community to define the knowledge sharing practice

in eCoP. The community perspective of knowledge

can be used to develop and support electronic com-

munities of practice. This perspective defines knowl-

edge as ’the social practice of knowing’ (Schultze and

Cox, 1998), and argues that learning, knowing and in-

novating are closed related forms of human activity

and inevitably connected to practice. The knowledge

resides in a community can be used to enable discus-

sion, and share ideas among the members of eCoP.

Moreover, the use of information and communica-

tion technologies enables knowledge sharing through

the mechanisms that allow sharing incidence based on

personal experience, discussing and debating issues

related to the domain of the community, posting and

responding to the queries (Wasko and Faraj, 2000).

In eCoP, the knowledge can be stored in the digital

form and transferred to others regardless of the loca-

tion of the individual who generated the knowledge

and who is going to receive it. Knowledge sharing in

eCoP is a process that exploits existing knowledge by

identifying, transferring, and applying to solve tasks

better, faster and cheaper (Christensen, 2007). How-

ever, members are often reluctant to share knowledge

others in the eCoP (Tamjidyamcholo et al., 2014).

Furthermore, Ardichvili et al. (Ardichvili et al.,

2002) conducted a qualitative study to understand the

motivation and barriers to participating in eCoP at

Caterpillar Inc. The study identified that the mem-

bers of the community are not willing to share their

knowledge because of the fear of criticism or mislead-

ing the other members. It has been shown in a recent

study (Agrawal and Snekkenes, 2017) that the partic-

ipants (IT professionals) of the communities were not

willing to participate actively in the absence of strong

motivation. ISPs may not want to disclose informa-

tion on eCoP that describes their organization’s secu-

rity status or any weakness. Therefore, it is important

to anonymize the knowledge sharing process (Fenz

et al., 2011). The role of trust in encouraging the ISPs

to share knowledge in eCoP is studied in (Gefen et al.,

2003), (Ratnasingam, 2005), (Fenz et al., 2011).

2.3 Underlying Theories

This study considers knowledge sharing behavior and

participation of ISP in eCoPs as an individual’s social

psychological process. Thus, one’s attitude, intention,

motivation, trust subsequently influence the behavior

of the individual. We adopted three theories in this

work to analyze the factors affecting the participation

of ISPs in eCoP. The theories are as follows:

2.3.1 Motivation Theory (MT)

Motivation refers to ”internal factors that impel action

and to external factors that can act as inducements to

action” (Locke and Latham, 2004). According to Fray

et al. (Osterloh and Frey, 2000), motivation to share

knowledge is driven by intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

Extrinsic motivations satisfy the instrumental needs

of a human. For instance, money, financial reward,

social rewards, increase in the status. Intrinsic moti-

vations are perceived by the values provided directly

within the work (Frey and Osterloh, 2001). For in-

stance, altruism drives many people to do something

for the enjoyment of doing the work.

2.3.2 Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

According to TPB theory, the human behavioral in-

tentions are determined by three factors: attitude, sub-

jective norms, and perceived behavioral control. At-

titude refers to the degree to which one evaluates the

behavior favorably or unfavorably. Subjective norm

is the perceived social pressure to perform or not per-

form the behavior. Perceived behavioral control is de-

fined as the degree to which a person perceives that

the decision to engage in a given behavior is under

his/her control (Jeon et al., 2011).

2.3.3 Perceived Trust Theory (PTT)

The role of trust in increasing the willingness to share

knowledge in an online community of practice is stud-

ied in (Usoro et al., 2007) where trust is conceptu-

alized into competence, integrity, and benevolence.

Competence-based trust defines the degree to which

a member believes that the community is knowledge-

able and competent. Integrity-based trust defines

the degree to which a member believes the commu-

nity to be honest and reliable (Mayer et al., 1995).

The benevolence trust considers the self-motivation

through a sense of moral obligation to become a part

of a community. Therefore, the individual that re-

ceives the knowledge in the community does not play

a major role in influencing benevolence-trust of the

person willing to share the knowledge. However, we

are more interested to understand the role of the trust

that is established based on the action of the per-

son receiving the knowledge, and not just by self-

motivation.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

This study is based on the principle of stated prefer-

ence technique (Brownstone et al., 2000) for estab-

lishing valuations. An online survey-based technique

is designed to collect the response from the ISPs. The

online questionnaire is distributed in one of the ISF

meetings where 56 ISPs participated in answering the

survey.

3.1 Questionnaire Design

An online quantitative questionnaire was created us-

ing LimeSurvey open source survey tool. The ques-

tionnaire was hosted on the project website (Agrawal,

2017). The online survey was available in both En-

glish and Norwegian. The respondents accessed the

online survey on their smartphone during the ISF

meeting. The survey consisted of 18 questions cov-

ering the topics on demography, working activities,

and preference for eCoP. The detail of the survey is

given in Appendix. The survey was conducted at

Information Security Forum (ISF) Norway meeting.

The questionnaire consists of three sections that are

as follows:

1. Demography - Questions related to age, gender,

job role, job location, type of organization, the

size of an organization.

2. Work activities - Questions related to daily tasks,

full-time or half-time ISP, the source used to col-

lect information, challenges associated with infor-

mation gathering.

3. Community-based knowledge sharing - Questions

on prior experience using eCoP, the nature of

eCoP, no. of members on eCoP, the domain

of eCoP, and the preferences related to sharing

knowledge, participation on eCoP. This part of the

questionnaire is created to analyze the concepts of

the above-mentioned theories (Ref. section 2.3).

3.2 Respondents

A total of 56 respondents (46 male, 9 female, 1 undis-

closed) volunteered to complete the online survey.

The majority of the respondents are working as a full-

time ISPs in Norway. A short introduction about the

research project is presented to the respondents at the

beginning of the workshop. The objective of the on-

line survey and the details of the various terms, used

in the questionnaire, are also presented to the survey

respondents. The survey had the option for the re-

spondents to decline their participation at any point

in time if they feel uncomfortable participating in the

survey.

3.3 Data Analysis

We collected data from 56 respondents through the

online survey. Since the study is restricted to the users

participating in only in the online CoPs, we rejected

the responses of six respondents as these respondents

participated only in the offline communities of prac-

tice. Subsequently, we rejected two more observa-

tions from the sample as they did not answer many

questions in the questionnaire. Therefore, our final

sample size consists of 48 observations. A dichoto-

mous data is considered as an output variable with

the values, ’yes’ and ’no,’ which signifies whether the

given user participates or does not participate in eCoP

respectively. Based on the study and argument pre-

sented in the studies (Little, 1978), logistic regression

fits well to this study. Ergo, logistic regression (also

called as logit) is used as a statistical technique to for-

mulate the results and findings. Hence, all predic-

tors are considered as categorical variables whereas

the participation in eCoP (Y

i

) is assumed as a dichoto-

mous or binary outcome. Furthermore, this study as-

sumes the covariates such as age, gender, educational

levels, occupational levels, the organizational size of

the respondents and number of hours spent on IS per

week as independent variables. Equation 1 summa-

rizes the main element of the logit model and Equa-

tion 2 expresses the probability of Y

i

.

Y

i

=

(

1 i f the i

th

sub ject is using eCoP

0 otherwise

(1)

y

i

= p(x

0

i

) =

exp(β

0

+ β

1

x

1i

+ β

2

x

2i

+ ... + β

n

x

ni

)

1 + exp(β

0

+ β

1

x

1i

+ β

2

x

2i

+ ... + β

n

x

ni

)

(2)

where

• y

i

can be considered as realization of output vari-

able Y

i

which takes the values 1 or 0 with proba-

bility value of p and 1 − p respectively.

• x

0

i

is i

th

vector of the independent variables as

mentioned earlier.

• β

0

, β

1

, β

2

, . . . , β

n

are the coefficients of fitted re-

gression models.

Equation 2 can be rewritten as log linear function

as given below which is further used in deducing the

final output.

logit(Y

i

) = log

p(x

0

i

)

1 − p(x

0

i

)

= β

0

+ β

1

x

1i

+ β

2

x

2i

+ ... + β

n

x

ni

+ ε

(3)

Furthermore, we have formulated the decision rule as,

the negative values of the logit of output variable will

result into non user of the eCoP whereas positive logit

value will represents the user of eCoP.

4 RESEARCH RESULTS

This section provides the statistical results of the lo-

gistic regression model fit which is formulated to in-

vestigate the research question RQ1 in this study.

4.1 Result I

The information about the demography of the ISPs

members is presented here. Table 1 tabulates the

statistics of the collected data. There are 35 ISPs with

university level education, i.e., an education degree

in bachelors, masters or doctorate in Information se-

curity and allied branches. The majority of the re-

spondents are males in the age group of 30 - 60 years.

75% of the respondents work full-time in IS domain

mainly affiliated to Information and communication

industry, Financial and insurance, business service,

health and social services sectors. Our findings also

Table 1: Summary of the demographic data of ISPs participated in the survey.

age sex edu level ocp level no emp no hrs

1 > 60 : 5 Female: 8 Asso. degree : 7 Unspecified : 1 5000- :13 0-10 : 6

2 21-30: 3 Male :40 B. degree :13 Administrative: 2 1000-4999:11 11-20: 6

3 31-40:14 Doc. degree : 3 CISO :13 100-499 : 7 21-30: 6

4 41-50: 9 HS diploma : 2 Other :19 0-10 : 6 31-40:17

5 51-60:17 M. degree :19 Researcher : 2 10-49 : 3 41- :13

6 Other : 2 Security Engineer :11 50-99 : 3

7 Tech. training : 2 Other : 5

highlight that the ISPs in our survey come from small

(employee strength 1-19), medium-sized (20-99) and

large (100+) companies (Iversen, 2013).

4.2 Result II

Based on the Equations 2 and 3, we have modeled our

data by fitting logistic regression model using R soft-

ware (R Core Team, 2013). In this model, we consid-

ered four independent variables which are age, gen-

der, no. of employees and no. of hours spent on IS

related tasks

1

. Table 2 presents the coefficients and

the significance of these variables. We can see that the

categorical variable no. of employees have all positive

coefficients, which indicates that the unit increment

in the no. of employees encourage the participation

in eCoP whereas the no. of hours spent on task re-

lated to IS has the negative coefficients. Ergo, it can

be inferred that the participation of ISPs, who work

for full-time or more in IS task, is low in eCoP.

To test the significance of these explanatory vari-

ables, under the null hypothesis all the coefficients

will take the value equal to 0. For example, H

0

: β

1

=

β

2

··· = 0, and H

a

:6= 0

From the Table 2, p-value for levels no emp100-

499(β

p

) and no emp1000-4999(β

q

) is 0.05 which is

statistically significant

2

. Hence, H

0

is rejected in the

study. The p-value of no hrs31-40(β

r

), no hrs41(β

s

)

is 0.03 and 0.09 which shows that levels have sig-

nificant effect on the probability of participating in

eCoP. Hence, the output variable can be explained in

terms of the odds ratios which can be obtained by

calculating the exponential of β

p

, β

q

, β

r

, β

r

i.e e

β

p

=

100, e

β

q

= 63, e

β

r

= 0.0075, and e

β

s

= 0.0252.

Therefore, we can write that:

3

• On average, for every one unit change in the num-

ber of employees, the log odds of being a user of

eCoPs (versus non-user) increases by 81.2.

1

All explanatory variables considered here are categori-

cal variables

2

We considered significance at 90% confidence level

3

Analysis is made on the basis of explanatory variables

which are statistically significant, non significant variables

can be excluded and one can remodel the system

• For a unit increase in the number of hours spent

on tasks related to the IS per week, the log odds

of being the use of eCoPs increase by 0.0164.

The variables age, gender have a slightly differ-

ent interpretation. For all age groups, the obtained

p-value is significantly high with an average value of

0.69 hence we can not reject the H

0

. In addition to

this we can see that the most of the variables are sta-

tistically non-significant.

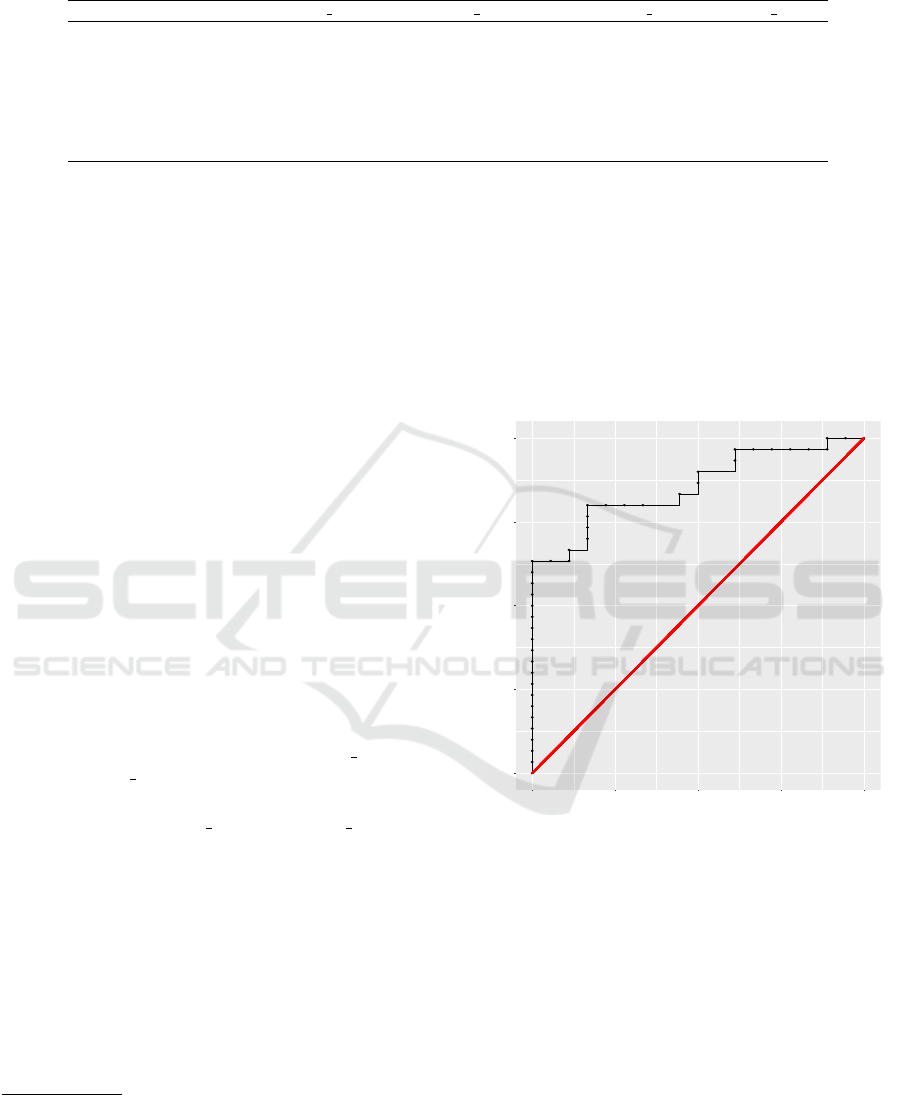

AUC= 0.8611

0.00

0.25

0.50

0.75

1.00

0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00

1−Specificity

Sensitivity

logit (user ~ age + sex + no_emp + no_hrs)

Figure 1: ROC curve for logistic regression model.

Thus, we can consider that the probability of par-

ticipating in eCoP is not affected by the demography

factors such as age, gender, and educational level.

Further, we used Receiver Operating Curve (ROC)

and area under ROC curve (AUC) to report perfor-

mance of the fitted model. ROC Curves describes

how well the fitted model can separate the two classes

0 and 1, and it also helps to identify the best threshold

for separating them. In the case of ROC curves, the

AUC plays an important role; higher the AUC bet-

ter the model in classification. Figure 1 represents

the ROC of the fitted logistic regression model and

AUC = 0.86, which can be considered as a high per-

formance for real life applications.

4.3 Result III

In this section, there are three factors related to work

activities of ISPs analyzed to see their effect on the

probability of ISPs in participating in eCoP. The fac-

tors are source of obtaining information required to

do the professional tasks, nature of the tasks, and the

challenges faced in obtaining the information. The

details of the factors and their variables can be ob-

tained from Appendix 7.

Table 2: Summary of estimated logistic regression model.

Var. Coef S.E. z-val Pr(>|z|)

(Int.) 0.85 3.51 0.24 0.81

age21-30 19.03 2935 0.01 0.99

age31-40 -2.90 2.62 -1.11 0.27

age41-50 0.32 2.72 0.12 0.91

age51-60 -1.35 2.52 -0.54 0.59

sexMale 2.04 1.35 1.51 0.13

no emp10-49 0.12 2.63 0.05 0.96

no emp100-499 4.63 2.33 1.98 0.05*

no emp1K-4.9K 4.14 2.12 1.95 0.05*

no emp50-99 0.91 2.01 0.45 0.65

no emp5K- 3.11 2.06 1.51 0.13

no empIDK 0.85 2.09 0.40 0.69

no hrs11-20 -3.22 2.44 -1.32 0.19

no hrs21-30 -1.69 1.95 -0.87 0.38

no hrs31-40 -4.90 2.26 -2.17 0.03*

no hrs41- -3.68 2.16 -1.70 0.09*

Table 3

4

shows that the variables [S1-S8] of

’source of information’ have positive coefficient

which signifies that the unit increment in the moti-

vation will increase the participation of ISPs in eCoP.

Variable S3 has statistically significant effect on the

participation of ISPs in eCoP. Variable S3 signifies

that respondents, who ask other professional experts

on communities of practice to obtain necessary infor-

mation to carry out their task, also participate in eCoP.

In a case of the usual activity that ISPs perform their

job tasks, the variable N7 has statistically significant

(p-value less than 0.1) effect on the participation of

ISPs in eCoP. The challenges, which are faced by ISPs

in obtaining the information for their job, do not have

statistically significant effect on eCoP participation. It

also signifies that we cannot predict the probability of

ISPs participating in eCoP by having any information

on the challenges that they face within the category

given under C1-C6.

4

The variable corresponding to Reference modality is

automatically considered as a reference by R GLM package

Table 3: Summary of variables under information source,

nature of job tasks, and challenges in obtaining information.

Var. Coef S.E. z-val Pr(>|z|)

(Int.) 11.37 3840.09 0.00 1.00

Source of information

S1 0.91 1.51 0.60 0.55

S2 Reference modality

S3 4.77 2.15 2.22 0.03*

S4 Zero entry in the response database

S5 1.11 1.69 0.66 0.51

S6 0.62 1.86 0.33 0.74

S7 2.99 9224 0.00 1.00

S8 0.12 2.01 0.06 0.95

Nature of tasks

N1 21.73 6522.64 0.00 1.00

N2 3.38 2.17 1.55 0.12

N3 Reference modality

N4 3.13 2.22 1.41 0.16

N5 2.49 2.41 1.03 0.30

N6 2.06 2.44 0.84 0.40

N7 5.05 2.66 1.90 0.06*

N8 20.94 6522.64 0.00 1.00

Challenges in obtaining information

C1 -14.66 3840.08 -0.00 1.00

C2 -17.53 3840.08 -0.00 1.00

C3 3.07 5989.08 0.00 1.00

C4 -18.16 3840.08 -0.00 1.00

C5 -19.26 3840.08 -0.01 1.00

C6 Reference modality

5 DISCUSSION

Knowledge sharing is an intentional behavior which

cannot be forced by someone (Gagn, 2009). People

participate in eCoP to exchange knowledge with the

others. Therefore, it is useful to analyze the knowl-

edge sharing behavior of ISPs in eCoP. The factors,

affecting the participation of ISPs in eCoP activities,

are investigated with the help of MT, TPB, PTT (re-

fer section 2.3). We modeled our data by fitting the

logistic regression model. In this model, we consid-

ered the variables of TPB, MT, and PTT to predict

the probability of participating in eCoP. The variables

are defined in the online questionnaire given in the

Appendix 7.

5.1 Motivation Theory

Table 4 presents that the determinants of motivation

have positive coefficients, which indicate that a unit

increment in the motivation will increase the partici-

pation of ISPs in eCoP. We considered seven factors

under the motivation theory. SQ05 corresponds to

intrinsic motivation, and SQ08, SQ10, SQ11, SQ13,

SQ15, SQ20 are extrinsic motivation. Out of 7 vari-

ables, only the p-value of SQ08 is less than 0.1.

Table 4: Summary of the variables under Motivation theory.

Var. Coef S.E. z-val Pr(>|z|)

Motivation

(Int.) -1.44 0.84 -1.72 0.09

SQ05 0.17 0.77 0.22 0.83

SQ08 1.31 0.72 1.82 0.07*

SQ10 0.60 0.88 0.69 0.49

SQ11 0.41 0.74 0.55 0.58

SQ13 0.68 0.76 0.90 0.37

SQ15 0.73 0.71 1.02 0.31

SQ20 0.62 0.90 0.69 0.49

Therefore, it can be concluded that SQ08 has sta-

tistically significant effect on the participation of ISPs

in eCoP. The ISPs tend to participate in eCOP more

if members in the community share information rele-

vant to them. It can be considered as one of the main

incentives for the ISPs as well.

5.2 Theory of Planned Behavior

Table 5 presents the summary of the three major de-

terminants of TPB, i.e. attitude, subjective norm, and

perceived behavioral control. We can see that the

variable SQ01, SQ06, SQ12, SQ14, and SQ22 have

positive coefficients, i.e. the unit increment in these

variables will signify the increment in the participa-

tion of ISPs in eCoP. The p-value of the variables

SQ22 and SQ12 is less than 0.1. Hence, SQ22 and

SQ12 have statistically significant effect on the partic-

ipation of ISPs in Norway in eCoP. SQ22 corresponds

to the statement ’my organization allows me to par-

ticipate on a community-based platform to share my

knowledge’ in the questionnaire.

Table 5: Summary of variables under Theory of planned

behavior (TPB).

Var. Coef S.E. z-val Pr(>|z|)

Subjective norm

(Int.) 0.13 0.48 0.26 0.79

SQ14 -0.09 0.78 -0.12 0.91

SQ22 2.16 0.88 2.44 0.01*

Attitude

(Int.) 0.51 0.52 0.99 0.32

SQ01 16.26 1455.40 0.01 0.99

SQ06 0.08 0.65 0.12 0.91

SQ07 -1.20 1.33 -0.91 0.37

Perceived behavioral control

(Intercept) -0.37 0.43 -0.85 0.40

SQ12 1.80 0.66 2.73 0.01*

In other words, the participation of ISPs in eCoP

can be decided by investigating if the organization

has any restriction on the employee to participate

in eCoP. SQ07 corresponds to the negative feelings

about knowledge sharing in eCoP [I do not share any-

thing as I am concerned about the sensitivity of my

information]. SQ07 is the only variable with the neg-

ative coefficient, which signifies that the unit incre-

ment in this variable will reduce the participation of

ISPs in eCoP. It can be learned from applying TPB

concepts that the variables of the subjective norm, and

perceived control behavior are the important factors in

influencing the participation of ISPs in eCoP.

5.3 Perceived Trust

In our study, we considered the competence and in-

tegrity aspects of trust to understand the preference of

the respondents towards knowledge sharing tasks in

eCoP.

Table 6: Summary of the variables under perceived trust

concept.

Var. Coef S.E. z-val Pr(>|z|)

Perceived Trust

(Int.) 0.044 0.49 0.09 0.93

SQ18 1.11 0.68 1.65 0.10*

SQ19 -0.08 0.62 -0.14 0.89

Table 6 presents the findings of the variable related

to Trust factor. SQ18 and SQ19 have the positive co-

efficient and hence has the positive effect on the par-

ticipation of ISPs in eCoP. Moreover, SQ18 is also

statistically significant in predicting the ISPs’ partici-

pation.

6 CONCLUSION

The main objective of the present study was to un-

derstand the present status of the participation of ISPs

in Norway in eCoPs in IS. To achieve this goal, we

analyzed various factors that help us predict the par-

ticipation of ISPs in eCoP.

In this study, we observed that the number of em-

ployees in the organization, and working hours in se-

curity area are the significant factors in predicting the

participation in eCoPs. Further, we observed that both

extrinsic and intrinsic motivation is positively corre-

lated with the participation in eCoP. The finding of

logistic regression points out that the participation of

ISPs in eCoP is statistically influenced by the factor

that other members of the community share relevant

information to the problems of ISPs. In other words,

we can expect high participation if we can ensure that

the members of the community will share informa-

tion that is useful to the participants. However, the

tendency to share knowledge decreases when it is per-

ceived that they are receiving irrelevant or not so use-

ful information from other members.

The application of TPB also led to some impor-

tant observation in this study. The probability of the

participation in eCoP is significantly increased if the

organization encourages the employee to participate

in the knowledge sharing activities. Typically, eCoP

needs information technology capabilities to establish

knowledge sharing process. The presence of the nec-

essary resources (in the form of platform, and service)

also enables the ISPs to participate in eCoP.

7 RESEARCH LIMITATION AND

FUTURE WORK

The response that we received from 48 participants

provides an initial insight into understanding the cur-

rent status of participation in electronic communities

of practice by ISPs in Norway. However, the findings

cannot be generalized to a large population because

of the small sample size of the respondents. Hence,

more studies are needed to generalize present study

findings. Furthermore, we collected the data from the

participants who volunteered for it. It signifies that

the response is collected from the people who had

enough time and interest to complete the survey. The

result might have differed if we had selected the par-

ticipants randomly. The future research will address

this issue by targeting large respondents and selecting

a random sample from it.

In our study, we mainly tried to understand the

preference of the members who are going to share

their knowledge. The receiver’s perspective is also

important in the context of knowledge sharing task.

Future research will aim to address this issue by col-

lecting the perspective of both the parties. It will help

to compare their preference and design the incentive

scheme along with the sharing model. The use of cat-

egorical variables in the logistic regression model can

also cause some issues. Therefore, we are investigat-

ing the possibility of adopting a linear scale in the fu-

ture data collection events.

REFERENCES

Agrawal, V. (2017). A survey on information sharing prac-

tices. www.unrizk.org/survey/index.php/766876. On-

line; accessed 06 September 2017.

Agrawal, V. and Snekkenes, E. A. (2017). An investiga-

tion of knowledge sharing behaviors of students on an

online community of practice. In Proceedings of the

5th International Conference on Information and Ed-

ucation Technology, ICIET ’17, pages 106–111, New

York, NY, USA. ACM.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Or-

ganizational Behavior and Human Decision Pro-

cesses, 50(2):179 – 211. Theories of Cognitive Self-

Regulation.

Ardichvili, A., Page, V., and Wentling, T. (2002). Virtual

knowledge-sharing communities of practice at cater-

pillar: Success factors and barriers. Performance Im-

provement Quarterly, 15(3):94–113.

Brown, J. S. and Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning

and communities-of-practice: Toward a unified view

of working, learning, and innovation. Organization

science, 2(1):40–57.

Brownstone, D., Bunch, D. S., and Train, K. (2000). Joint

mixed logit models of stated and revealed preferences

for alternative-fuel vehicles. Transportation Research

Part B: Methodological, 34(5):315 – 338.

Christensen, P. H. (2007). Knowledge sharing: moving

away from the obsession with best practices. Journal

of Knowledge Management, 11(1):36–47.

Fenz, S., Parkin, S., and v. Moorsel, A. (2011). A commu-

nity knowledge base for it security. IT Professional,

13(3):24–30.

Frey, B. S. and Osterloh, M. (2001). Successful manage-

ment by motivation: Balancing intrinsic and extrinsic

incentives. Springer Science & Business Media.

Gagn, M. (2009). A model of knowledge-sharing motiva-

tion. Human Resource Management, 48(4):571–589.

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., and Straub, D. (2003). Trust

and tam in online shopping: An integrated model.

MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems,

27(1):51–90. cited By 2452.

Ho, K., Jarvis-Selinger, S., Norman, C. D., Li, L. C.,

Olatunbosun, T., Cressman, C., and Nguyen, A.

(2010). Electronic communities of practice: guide-

lines from a project. Journal of Continuing Education

in the Health Professions, 30(2):139–143.

Iversen, E. (2013). Norwegian small and medium-sized en-

terprises and the intellectual property rights system:

exploration and analysis.

Jeon, S., Kim, Y.-G., and Koh, J. (2011). An integrative

model for knowledge sharing in communitiesofprac-

tice. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(2):251–

269.

Johnson, C. M. (2001). A survey of current research on on-

line communities of practice. The Internet and Higher

Education, 4(1):45 – 60.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legiti-

mate peripheral participation. Cambridge university

press.

Liedtka, J. (1999). Linking competitive advantage with

communities of practice. Journal of Management In-

quiry, 8(1):5–16.

Little, R. J. (1978). Generalized Linear Models for Cross-

classified Data from the WFS. World Fertility Survey,

International Statistical Institute.

Locke, E. A. and Latham, G. P. (2004). What should we

do about motivation theory? six recommendations for

the twenty-first century. The Academy of Management

Review, 29(3):388–403.

Mathwick, C., Wiertz, C., deRuyter, K., served as edi-

tor, J. D., and served as associate editor for this ar-

ticle., E. A. (2008). Social capital production in a vir-

tual p3 community. Journal of Consumer Research,

34(6):832–849.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., and Schoorman, F. D. (1995).

An integrative model of organizational trust. The

Academy of Management Review, 20(3):709–734.

Osterloh, M. and Frey, B. S. (2000). Motivation, knowl-

edge transfer, and organizational forms. Organization

Science, 11(5):538–550.

Probst, G. and Borzillo, S. (2008). Why communities of

practice succeed and why they fail. European Man-

agement Journal, 26(5):335 – 347.

R Core Team (2013). R: A Language and Environment for

Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical

Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0.

Ratnasingam, P. (2005). Trust in inter-organizational

exchanges: A case study in business to business

electronic commerce. Decision Support Systems,

39(3):525–544. cited By 87.

Schultze, U. and Cox, E. L. (1998). Investigating the contra-

dictions in knowledge management. pages 155–174.

Tamjidyamcholo, A., Baba, M. S. B., Shuib, N. L. M., and

Rohani, V. A. (2014). Evaluation model for knowl-

edge sharing in information security professional vir-

tual community. Computers & Security, 43:19 – 34.

Usoro, A., Sharratt, M. W., Tsui, E., and Shekhar, S. (2007).

Trust as an antecedent to knowledge sharing in virtual

communities of practice. Knowledge Management Re-

search & Practice, 5(3):199–212.

Von Krogh, G. (1998). Care in knowledge creation. Cali-

fornia management review, 40(3):133–153.

Wasko, M. M. and Faraj, S. (2000). It is what one does:

why people participate and help others in electronic

communities of practice. The Journal of Strategic In-

formation Systems, 9(2-3):155 – 173.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning,

meaning, and identity. Cambridge university press.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., and Snyder, W. (2002). Cul-

tivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Man-

aging Knowledge. Harvard Business School Press,

Boston, MA, USA.

Wiertz, C. and de Ruyter, K. (2007). Beyond the call of

duty: Why customers contribute to firm-hosted com-

mercial online communities. Organization Studies,

28(3):347–376.

APPENDIX

The survey should only take 10-12 minutes. This sur-

vey is completely anonymous. The record of your sur-

vey responses does not contain any identifying infor-

mation about you.

Demography

1. What is your age group (in years)? Choose one of

the following answers

• 21-30

• 31-40

• 41-50

• 51-60

• >60

2. Please specify your gender. Choose one of the

following answers

• Female

• Male

• Decline to answer

3. What is the highest level of formal education do

you have? Choose one of the following answers

• Primary school

• High school graduate, diploma or the equiva-

lent

• Bachelors degree

• Trade/technical/vocational training

• Associate degree

• Master’s degree

• Doctorate degree

• Professional degree

• Other

4. Please select the country where you are currently

employed. Choose one of the following answers

• Norway

• Other

5. What best describes the type of organization you

work? Choose one of the following answers

• Financial and insurance

• Mining and extraction

• Information and communication

• Agriculture, forestry and fishing

• Electricity, gas, damp, and heating supply

• Transport and storage

• Accommodation and service

• Health and social services

• Production industry

• Business service

• Culture, entertainment and leisure

• Other

6. Which of the following most closely matches your

job role? Choose one of the following answers

• Chief Information Security Officer (CISO)

• Data protection officer

• Security Engineer

• Legal (advocate)

• IT professional (Systems administrator, pro-

grammer)

• Journalist

• Researcher

• Administrative (e.g. secretary, assistant)

• Accountant

• Other

7. Counting all locations where your employer op-

erates, what is the total number of persons who

work there? Choose one of the following answers

• 0-10

• 10-49

• 50-99

• 100-499

• 500-999

• 1000-4999

• 5000-

• I don’t know

Work Activities

8. How many hours per week do you spend on infor-

mation security related tasks in your job responsi-

bilities? Choose one of the following answers

• 0-10

• 11-20

• 21-30

• 31-40

• 41-

9. Which of the following tasks do you perform

daily? Check all that apply

Develop an information security policy for the

organization

Co-ordinate the information security activities

at the organizational level

Share my expertise with my colleagues inside

the organization

Share my expertise with my colleagues outside

the organization

Perform risk and threat analysis of the informa-

tion security for the organization

Reporting to the top management team about

the information status of the organization

10. What is the most frequent activity do you perform

to carry out your job tasks? Choose one of the

following answers

• Look for information [N1]

• Process information [N2]

• Create new information [N3]

• Solve problems [N4]

• Make decision [N5]

• Interact with the peers [N6]

• Help others to do their job [N7]

• Other [N8]

11. Which source do you mostly use to obtain the nec-

essary information needed to carry out your tasks?

Choose one of the following answers

• Personal experience [S1]

• Government Agency (e.g. Datatilsynet) [S2]

• Asking other professional experts on Commu-

nities of practice [S3]

• Consultancy firm [S4]

• Interview/meeting with your team [S5]

• Internal document/manual of your company

[S6]

• Social media (e.g. LinkedIn) [S7]

• Other [S8]

12. What is the most challenging part in obtaining

the information required to complete your tasks?

Choose one of the following answers

• The information is available in the fragmented

manner [C1]

• The information is outdated and cannot be ap-

plied to recent problems [C2]

• The information is untrustworthy as I don’t

know the source [C3]

• The information is difficult to find, time-

consuming [C4]

• The information has a low relevance to my

problem [C5]

• Other [C6]

Community-based Knowledge Sharing

13. Do you participate in a community-based knowl-

edge sharing practice?

• Yes

• No

14. What is the domain of the community where you

are mostly an active member? [answer only if you

select ’yes’ in Q13]

• Information security

• Other

15. Please select the statement that is valid for the

community where you participate most. [answer

only if you select ’yes’ in Q13]

• The community has both online and offline ac-

tivities

• The community has only online activities

• The community has only offline activities

16. What is the estimated number of members in the

community? [answer only if you select ’yes’ in

Q13]

• 10-99

• 100-499

• 500-999

• >1000

• I don’t know

17. Please mark the statement(s) that is(are) valid for

you in terms of participating in the community-

based knowledge sharing tasks. Check all that ap-

ply

My knowledge is very personal to me. I don’t

like to share it with others [SQ01]

Sharing my knowledge improve my reputation

within the community [SQ02]

When I share my knowledge in the community,

I expect to get back knowledge whenever I need

it [SQ03]

When I share my knowledge in the community,

I believe that my questions will be answered in

the future [SQ04]

Sharing my knowledge with others gives me

pleasure [SQ05]

My knowledge sharing with other members is

valuable to me [SQ06]

I do not share anything as I am concerned about

the sensitivity of my information [SQ07]

Members on the community share information

relevant to my problems [SQ08]

I share my knowledge only when the commu-

nity has the option for the face-to-face commu-

nication [SQ09]

Participating in the community decreases the

time needed for my job responsibilities [SQ10]

Participating in the community increases the ef-

fectiveness of performing job task [SQ11]

I have the resources necessary to share knowl-

edge in the community [SQ12]

I participate in the community to establish new

connection with the members [SQ13]

People who are important to me expect that

I should participate in the knowledge sharing

task in the community [SQ14]

By sharing knowledge within community, I find

better solution for my problem [SQ15]

I share the work reports and official docu-

ments obtained from inside the organization

with other members [SQ16]

I share my expertise from my education, train-

ing, experience with other members [SQ17]

I trust the information that I receive from other

members in the community [SQ18]

I trust the information only if I know the iden-

tity of the member whom I am sharing my

knowledge with [SQ19]

I get the latest (up-to-date) information/answers

for my question in the community [SQ20]

I do not share my knowledge on a commu-

nity because I may lose my competitive edge

[SQ21]

My organization allows me to participate on a

community-based platform to share my knowl-

edge [SQ22]

My job profile allows me to participate on a

community-based platform to share my knowl-

edge [SQ23]

I have everything that I need to carry out my

job tasks effectively. Therefore, I do not need

to participate [SQ24]

I am willing to participate if the community is

available as an online platform [SQ25]

Final

18. Any other comments? Please write your answer

here: