International Labor Migration of Health Care Workers in Japan

Under the Economic Partnership Agreement: The Case of Indonesian

Nurses

Kazumi Murakumo

Doctoral Program in International and Advanced Japanese Studies, University of Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan

s

1730058

@

s.tsukuba.ac.

jp

Keywords: Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA), International labour migration, Health care workers, Falling birth-

rate and depopulation.

Abstract: With falling birth-rate and depopulation accelerating in Japan, the country relies on international labour in

various fields. The Japanese government began to receive Indonesian (2008), Filipino (2009), Vietnamese

(2014) nurses, and health care workers under the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA). Meanwhile,

many of these candidates cannot pass the national exam and go back to their countries after three

years, although they entered Japan as a solution of chronic labour shortage in health care fields. This

research demonstrates that there is mismatch between Japanese and Indonesian governmental policies that

leads to a consequent loss of opportunities for the nurses. This paper analyses the interviews with two

nurses who passed the national examination and reside in Japan and six ex-candidate Indonesian nurses who

returned to their country as well as, an interview at the Japan International Corporation of Welfare Services

(JICWELS) and Badan Nasional Penempatan dan Perlindungan Tenaga Kerja Indonesia (BNP2TKI). It

examines what institutional issues exist under the current Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) system.

The collected voices and data reflect the actual situation for both receiver and sender countries to

understand both countries’ policy mismatch. As the EPA program and research are still ongoing, we also

aimed to find out more on the suitable environment for international labour migrations to enter Japan from

the perspective of the EPA sustainability framework.

1 INTRODUCTION

In this paper we will conduct an analysis focusing on

the foreign nurses coming to Japan, whom Japan

started to accept in 2008 through the Economic

Partnership Agreement (EPA).

This year, 2017, marks the 10th year since Japan

started to accept nurses in accordance with the EPA.

For our analysis, we focus on Indonesian nurses

who, in accordance with the EPA, come to Japan.

There are three reasons for selecting Indonesian

nurses. First, Indonesia is the first country that

started sending nurses to Japan in 2008. Second, the

author speaks Indonesian (Bahasa Indonesia). Third,

we conducted an interview in Indonesia on a topic

that was not covered by previous studies.

In previous studies, the nurses who came to

Japan in 2008 were called the “first-batch” and those

who came in 2009 were called the “second-batch”

(Kawaguchi, Hirano & Ohno 2009, 2010c). We use

the same terminology in this article. At present,

Japan accepts foreign nurses based on the EPAs

from three countries: Indonesia, Philippines, and

Vietnam.

Ogawa et al. (2010) argue that ‘nurse and care

worker candidates who come to Japan through the

EPAs are one of the solutions to labour shortage in

the field of nursing and care in Japan’. The survey

conducted by above mentioned authors in 280

hospitals, shows that 51.8% of the hospitals

responded: “we are well aware of it” to the question

“Are you aware that Japan is trying to introduce

foreign nurse and care worker candidates based on

EPAs?” On the other hand, regarding reasons for not

willing to accept candidates, the answer “there are

concerns regarding their ability to communicate with

patients” was the most common with 203 hospitals,

while 142 hospitals responded: “It will increase the

workload of the staff in charge of education, and

Murakumo, K.

International Labor Migration of Health Care Workers in Japan Under the Economic Partnership Agreement: The Case of Indonesian Nurses.

In Proceedings of the 4th Annual Meeting of the Indonesian Health Economics Association (INAHEA 2017), pages 65-72

ISBN: 978-989-758-335-3

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

65

there are concerns about Japanese language

proficiency.

Previous studies have shown that medical

institutions are aware of the EPA and that there is a

strong interest towards foreign nurses. Also, it is

evident that hospitals that wish to accept foreign

nurses and care worker candidates have expectations

for securing labour power personnel: “…as part of

an international contribution and exchange… [and]

to resolve labour shortage even if only slightly,” and

“we expect them to add to the workforce as nurses in

the future.” At the same time, the following

responses were given by those who were reluctant to

accept foreign nurses: “There are concerns with

regard to their ability to communicate with the

patients” and “It will increase the workload of the

staff in charge of training nurses, there are concerns

about Japanese language proficiency.” These

hospitals indicated their concern for the Japanese

language proficiency of the candidates and for

looking after the candidates from acceptance until

they pass the national examination. It appears that

they are aiming to resolve the shortage of human

resources on the job site but at the same time they

are concerned that the burden on those already

working may increase by accepting the foreign

candidates (Ogawa et al. 2009, 2010).

Previous studies conducted a survey of hospitals

but they did not include interviews that involved

nurses who were working in the field. Hence, in this

study we discuss the opinion of nurses in response to

the limitations of the previous studies.

We would like to describe the related

organizations of Japan and Indonesia to better

understand the agreement between these two

nations. In Japan, accepting country, the Japan

International Corporation of Welfare Services

(JICWELS) is responsible for accepting nurses. In

Indonesia, the sending country, Badan Nasional

Penempatan dan Perlindungan Tenaga Kerja

Indonesia (BNPPTKI) is responsible for sending

nurses to Japan.

The aim of this paper is to provide an empirical

evidence on the implementation of the EPA. We

believe that this study can trigger opportunities for

promoting new immigration policy. Moreover, new

ways of approaching the issue of immigration in the

field of nursing and care taking based on the

implementation of the EPA scheme are being

observed.

In addition, in the aspect of international

relations, there is a possibility that effective

implementation of the EPA system can become one

of the conditions for acceptance of foreign workers

to Japan. Therefore, the EPA can exceed the level of

being a means for solving a problem of lack of

working power and affect the immigration policy of

Japan.

To understand the implementation process of the

EPA, the study addresses the following research

questions: Does the current state of foreign nurses

coming to Japan within the framework of the EPA

reflect an effective functioning of the policies? Are

there any issues that can be resolved regarding

foreign nurses?

Our research findings demonstrate that there is

an impact on nurses’ economic wellbeing in

Indonesia. The significance of the present study is

that it indicates how the movement of human

resources between nations may act as a framework

that plays the role of resolving the global problem of

aging societies with low birth-rate. We attempt to

bring to light the possibility that there may be

implications with respect to international relations.

The national examination results of the nurses

who come to Japan through the EPA are reported in

Japan each year. We believe a statistical data on the

movement of nurses may reveal problems faced by

the Indonesian nurses as well as problems faced by

the accepting hospitals, which arise from accepting

them. The number of nurses who pass the

examination is small and the overall passing rate is

low (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2017).

We argue that foreign nurses and care worker

candidates will become expert professionals of

considerable importance in the future for the

countries faced by an aging society with low

birthrate, not only in Japan but in an international

community. Hence, a careful review of the process

of the acceptance of nurses and care worker

candidates through the EPA which is currently

taking place in Japan is likely to become a model

case for an international community.

2 METHODS

The research method that was employed is

interviewing different stakeholders. We conducted

analysis based on interviews with two Indonesian

nurses residing in Japan and six ex-candidates who

returned to Indonesia. The interviews conducted

with nurses were aimed at discussing the EPA

program. Numbers are used to keep the names of

participants anonymous (e.g., Nurse 1, and Nurse 2).

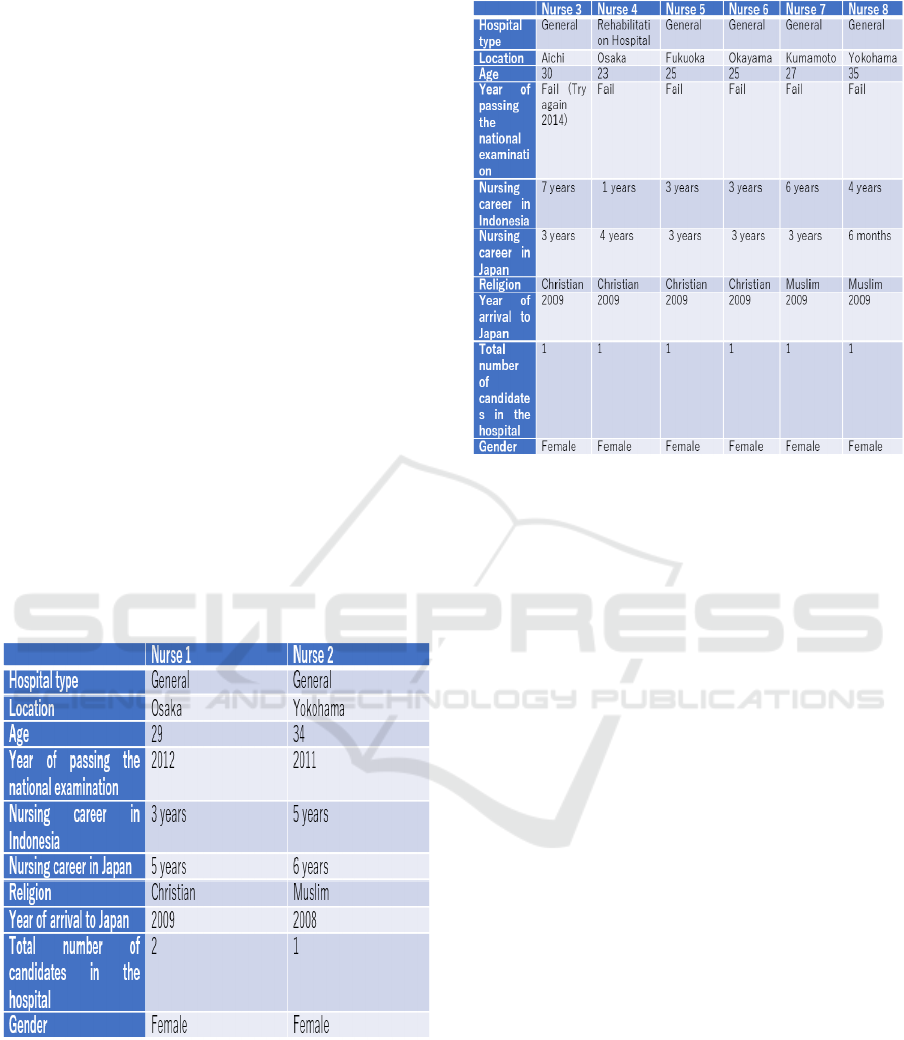

(TABLE 1)

In addition, interviews were conducted with the

accepting hospitals directors of nursing where nurses

INAHEA 2017 - 4th Annual Meeting of the Indonesian Health Economics Association

66

practiced and passed the national examination in

Japan. We were able to interview the directors of

nursing departments in two hospitals in Japan about:

(1) the circumstances leading to acceptance; (2)

support system for nurses; (3) difficulties that

emerged after accepting the nurses.

Two hospitals in Japan were selected for this

study. The two hospitals that interviews were

conducted are among of few hospitals that produced

successful candidates who passed the Japanese

national examination (Ogawa et al. 2009, 2010).

Following the research ethics, we explained the

purpose of the interview and all of the participants

signed the consent form.

In Indonesia, the author conducted an interview

in the government office of Badan Nasional

Penempatan dan Perlindungan Tenaga Kerja

Indonesia (BNPPTKI) in Jakarta as a first Japanese

intern. The Director of Badan Nasional Penempatan

dan Perlindungan Tenaga Kerja Indonesia

(BNPPTKI) was interviewed about: (1) the EPA

program; (2) existing implementation problems; (3)

future plans regarding the implementation of the

EPA program. In addition, six ex-EPA nurses from

the second-batch who came to Japan were

interviewed. The interviews were conducted in

Indonesian language. (TABLE 2)

Note: Data was collected and developed by author

Figure 1: Interview participants (nurses) in Japan

Note: Data was collected and developed by author

Figure 2: Interview participants (nurses) in

Indonesia.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Survey in Japan: Directors of

Nursing Departments and Nurses

First, we report the points of view of the directors of

nursing departments of the two hospitals where we

conducted interviews and collected data regarding

the shortage of nurses in Japan. At the hospital,

which agreed to cooperate with the survey in August

2013 there was a shortage of doctors and nurses and

challenges of hiring nurses.

Director of the nursing department in the

hospital pointed out that there is a shortage of

doctors and nurses. “Hiring nurses on a large scale is

taking place mainly at large hospitals in urban areas

and there are concerns that local hospitals may

suffer”.

It is the patients and their families who will face

problems because of shortage of doctors and nurses.

The more specialized the hospital, the more

important the number of doctors and nurses for the

development of a healthy hospital environment. The

interviews revealed the possibility that the shortage

of nurses may directly affect the revenue of the

hospitals.

The hospital, which agreed to cooperate with us

in December 2013 stated: “The Ministry of Health,

International Labor Migration of Health Care Workers in Japan Under the Economic Partnership Agreement: The Case of Indonesian Nurses

67

Labour and Welfare says ‘one nurse should take care

of seven patients’ but, in reality, it is not easy to do

this under the current circumstances. There are 314

beds in our hospital

and there are about 100 nurses

that most of them work on a full-time basis.”

To

the question of difficulties faced by accepting

foreign nurses, the director of nursing department

provided the following answer: “

We encountered

no problems by accepting foreign nurses. The nurse

who was hired had good nursing skills, good

communication skills and she was also a hard-

working person. Therefore, we cooperate and

support each other. We tried hard and helped her to

pass the national examination.”

Data from the Ministry of Health, Labour and

Welfare and the Japan Nursing Association indicates

that, from the viewpoint of the international

community, the sufficient number of nurses are not

secured for one patient in Japan and there are

concerns about the lack of nurses. They emphasise

that "The greater the number of nurses per hospital

bed, which means 7 [patient] to 1 [nurse], the better

the patient safety and it can provide with the highest

quality.” Based on the analysis of the interviews and

statistical data, we conclude that shortage of nurses

is a social problem that requires much debate. The

Japanese government sees it as an “urgent issue” and

it has been brought into question in the National

Assembly.

In view of the current situation in Japan, we

believe that foreign nurses are important human

resource that should be treated in the same way as

Japanese nurses, and we also think that it should

be a requirement for them, as it is for Japanese

nurses, to pass the national examination since they

are dealing with people’s lives. In reality, they strive

to pass the national examination while working at

host hospitals.

According to the rules, the nurses are required to

pass the examination within three years after coming

to Japan and if they fail, they need to return to their

home country. Based on Japan-Indonesia Economic

Partnership Agreement Foreign Nursing, “we have

been accepting candidates for nurse/nursing care

worker candidates, and a cumulative total of 1,562

people have entered the country. Acceptance from

these three countries is not done as a response to the

labor shortage in the field of nursing and nursing

care but rather from the viewpoint of strengthening

cooperation of economic activities as a result of

negotiations based on a strong request from the

partner country.”

The interviews and statistical data from the

hospitals indicate that nurses are expected to have

advanced “expertise.” It is required that they should

have high levels of expertise with an increased

workload which becomes the cause of failure in

national examination. The data indicates it is

important to secure human resources in the nursing

field which, is current and future issue of Japan.

(The House of Representative, Japan 2006).

We were able to understand the actual situation

of the shortage of nurses in Japan, however, there

are also limitations that the EPA has. Specifically,

the official view of the Ministry of Health, Labour

and Welfare is that with regard to the acceptance of

foreign nurses, nurse candidates who come to Japan

based on the EPA are not a solution to the shortage

of workers. We assume the government and those in

the actual field may have different outlooks

concerning accepting nurses in Japan.

Hospitals that accept nurses are expected to be

responsible for providing training for nurses with the

purpose of preparing them for acquiring national

qualifications. The interviews led to new questions

about whether the burden on the accepting hospitals

would increase or leaving hospitals unable to accept

nurses in the future, if the purpose of accepting

nurses were not to resolve labor shortage.

It will have a great impact on the international

community if Japan constructs a framework that will

allow the nurses coming to Japan within the

framework of EPAs to settle down in Japan as

members of the Japanese society instead of having a

status of foreign workers. The framework of

the current EPA has limitations in terms of people-

to-people exchange, but the fact that the Ministry of

Health, Labour and Welfare as well as the Ministry

of Foreign Affairs have set aside a budget to

implement the EPA (Ministry of Health, Labour and

Welfare 2013) suggests its importance as a state

policy.

Interviews of nurses who are influenced by the

policies between nations cannot be overlooked. We

interviewed two Indonesian nurses who agreed to

cooperate with the study. Both passed the

challenging national examination. Following is a

chronological analysis of the interviews.

The interviews were conducted in the hospital.

We interviewed a “second-batch” Indonesian nurse

(see Table 1) who came to Japan in 2009 and the

director of nursing department of the same hospital

separately. The director of nursing department

mentioned: “It's not difficult to accept (the nurses)”

and “nurses are faced with the challenge of passing

national examination.”

The nurses were asked the following questions:

(1) Are there any discrepancies between the

treatment you receive at the accepting hospital and

INAHEA 2017 - 4th Annual Meeting of the Indonesian Health Economics Association

68

what was explained to you during the briefing at the

time of departure from Indonesia?

(2) Did the hospital support you until you passed?

(3) Are there any difficulties that you face at the

hospital in Japan?

The common difficulty to both the nurse and the

director of nursing department, as their responses

revealed, was that the nurse was unable to speak

Japanese at the early stages of arrival in Japan.

However, the director of nursing department

responded that “although there were problems with

the language, no complaints were received from the

patients as there are no significant differences in

medical skills between Japan and Indonesia.” Also,

the director stated that “the hospital had also hoped

the nurse would pass the national examination and

that it was not only for the purpose of human

resource development but also for resolving the

problem of shortage in staff.”

The response from the director of nursing

department in the interview indicated that the nurse

had a positive effect on other Japanese staff in the

hospital by showing them that she was making an

effort. Although she had difficulty understanding

Japanese, the hospital created a good working and

learning environment for her. To answer the

questions on hospital support until national

examination and difficulties that she faced at work

in Japan, the nurse mentioned that the hospital used

a unique technique to help her learn Japanese and

obtain national qualification. For example, an

acquaintance of the director of nursing department (a

retired nurse) taught her medical terms three times a

week.

The hospital encouraged the nurse to set aside

time for studying in the afternoon, while working in

the morning, and the Administration Division of the

hospital properly handled and explained the

Japanese system (income tax, pension system, etc.)

regarding her salary. This led to trust and also

resulted in her passing the national examination

despite the language barrier and life obstacles, which

she overcame with support of the hospital.

Finally, with respect to the question on

differences between the treatment received at the

hosting hospital and what was told prior to coming

to Japan the nurse mentioned her salary. Prior to

departure, she was told at the briefing that her salary

would be around 200 thousand yen, which was

guaranteed in Japan. However, the actual amount

she received was different as dormitory fees and

taxes were deducted, but she said she found it

acceptable because, as mentioned above, the

Administration Division explained about the

Japanese tax system and miscellaneous fees to her in

detail.

At the same time, data revealed that among

nurses who came to Japan in the second-batch, there

were colleagues of the nurses who returned home

before finishing their contracts in Japan. The reason

was the hospital did not set aside time for them to

study, the salary was different from what they had

been initially told before departure, or they had been

assigned to a local region where daily conversation

was in a dialect, making it difficult to learn

Japanese. We found that the difference of what was

told at the briefing and the reality was the problem.

Our next step, was to conduct individual

interviews in December 2013 with a nurse who

came to Japan in 2008 in the “first-batch” and the

director of nursing department.

The nurse indicated that the Japanese national

examination was an issue in her answer to the

question on discrepancies between the treatment she

received at the accepting hospital and what was

explained to her during the briefing at the time of

departure from Indonesia. She said that during the

briefing in Indonesia, they were told that they would

be able to be involved in medical care as a nurse

upon arriving in Japan and she did not know she

needs to take the national examination. Both the

nurse and the accepting hospital were confused

about this and we were able to confirm that there

was in fact, a miscommunication in Indonesia and

Japan. We realized that this is an important issue

that has the possibility of developing into a problem

between states, and movement of people that the

international community was concerned about, since

Japan started accepting foreign nurses in 2008.

Regarding the support system of this hospital,

the work shift system was designed so that the nurse

could work in the morning and studied in the

afternoon. In addition, prior to the national

examination, the nurse was sent to Tokyo Academy

(vocational school) to attend a national examination

intensive course. In this way, the nurse herself and

the hospital worked together to pass the national

examination. The nurse told us that, although the

work is demanding, as she works in the field of

critical care medicine, she finds it very rewarding

and she cannot imagine returning home to Indonesia.

Also, she has been wearing a scarf to cover her

head, which is worn by Muslim women, since she

arrived in Japan and the hospital also respected her

wishes. The hospital stated that no complaints had

been received from the patients thus far, and there

were no concerns about religion as the time and

place for prayer had been set aside within the

International Labor Migration of Health Care Workers in Japan Under the Economic Partnership Agreement: The Case of Indonesian Nurses

69

hospital and she made sure her professional

responsibilities were not affected.

It became clear that both the hospitals and the

nurses had undergone various forms of trial and

error at the two hospitals with respect to acceptance.

We believe information was not shared fully

between the countries of Japan and Indonesia. As a

review of the interviews, we conclude that, first, the

explanation that was given to the first and second-

batches when coming to Japan was neither clear nor

sufficient.

Second, the way the nurses are treated differs

depending on the accepting hospital. The present

survey showed that Indonesian nurses are a valuable

workforce and the nurses themselves find the

nursing job rewarding. However, it seems that the

above-mentioned problems suggest the EPA

framework is not fully functioning yet.

3.2 Director of BNPPTKI and Ex-

Candidates

The interview results by Badan Nasional

Penempatan dan Perlindungan Tenaga Kerja

Indonesia (BNPPTKI), which have not yet been

disclosed in Japan, are as follows. First, the director

and the dispatching organization, are concurrent in

making efforts to ensure that as many candidates as

possible pass the national examination. To the

question “What is the problem?” we received the

answer that there was a miscommunication during

dispatching the first- and second-batch in regard to

passing the national examination in Japan.

The interviews revealed that various problems

had arisen during three years after 2008 due to

miscommunication between Japan and Indonesia.

Second, to reflect on the EPA program, the

director stated that, “We would like two candidates

to be accepted in one hospital,” and “BNPPTKI

cannot request the system of acceptance of the

hospital. It is responsibility of Japanese government

and candidates”.

We will carefully examine this problem in the

future based on the actual interview results of two

hospitals. Third, the Indonesian government still

sees many prospects with respect to the policies of

the EPA. To reflect on the future plan about the EPA

program, the answer was: “We are preparing to

increase the briefing and testing venues in Indonesia

to make it easier for more candidates to apply to the

EPA program.” It is desirable for both Japan and

Indonesia to continue their collaboration.

Next, we conducted a follow-up interview with

ex-nurse candidates who came to Japan in the

second-batch but returned home without passing the

national examination. As we have already mentioned,

careful examination is required on the issue of

whether there is a difference in acceptance among

hospitals. We hope to shed light on this issue faced

by those working in the field, based on the

interviews with the ex-nurse candidates who

returned home.

The following paragraph demonstrates the

results of the interviews of six ex-candidates, which

were conducted in August 2013.

First, the interviews revealed that there were

numerous comments regarding the accepting

hospitals. The most common comment was that they

would have passed the national examination if there

had been no difference in treatment among the

hospitals.

According to interviews with nurses, “The

hospital’s treatment had caused me to become

unmotivated to pass the national examination. I was

only able to work in the capacity of a nurse assistant,

which did not lead to the improvement of my skills.

I wanted to pass and continue working as a nurse in

Japan.” (Nurse 8) “I do not wish to be involved in

medical care even if I go back because people will

consider the three years in Japan as a period of

absence during which I was not involved in medical

care.” (Nurse 3, Nurse 6 & Nurse 7). Lastly, “I

would like to try again if I had the chance” (Nurse 3,

Nurse 5 Nurse 6 Nurse 7 & Nurse 8). The reasons

were that the wages of nurses are low in Indonesia.

In future studies we would like to investigate

whether differences in nurses preparation to national

examination are caused by hospitals or any other

factors by exploring the following questions:

(1) What are the differences in support of work and

preparation routine to the challenging national

examination at the hospital?

(2) What are the issues of acceptance system in the

hospital?

(3) How do nurses get a job in Indonesia after they

return to Indonesia?

Based on the follow-up interview with those who

returned home, we believe in the future, it is

necessary to carefully observe, the circumstances of

the issue regarding the treatment and system that the

candidates themselves are unable to overcome even

if they wished to work in Japan.

4 CONCLUSION

First, regarding the cause of conflicting information

in the differences in policies of relevant authorities

INAHEA 2017 - 4th Annual Meeting of the Indonesian Health Economics Association

70

on the acceptance and dispatch, the interviews in the

Japan International Corporation of Welfare Services

showed that its way of thinking is not different from

that of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

For example, they do not see the nurses come to

Japan from Indonesia with the aim of supporting the

labour shortage.

On the other hand, the interviews of the

Indonesian Agency for Overseas Placement and

Protection revealed that Indonesia, the dispatching

country, views their activities as a contribution to the

resolution of labour shortage. This may be one

reason for the miscommunication between Japan and

Indonesia.

Second, the interviews with the first and second-

batch, and the candidates that returned home

revealed that there is a difference in the acceptance

system from hospital to hospital. However, case

studies of hospitals that accepted candidates who

failed the national examination are not conducted,

yet. This topic remains to be explored in the future.

Both the candidates and the accepting hospitals

indicate language barrier as a factor to explain the

low examination pass rate. We would like to point

out that improvement in Japanese language ability

depends on how much time the accepting hospital

sets aside for work and study.

However, the level of the examination must not

be lowered from an ethical viewpoint, as it is an

occupation that concerns human life.

Third, when there is a difference regarding the

EPA between the signing countries, there is a

possibility that it may develop into problems

involving the candidates as well as international

relations. We conclude, based on interviews that it is

likely to develop into international relations. We

consider that, although Japan currently has a good

relationship with Indonesia, new demands arise

between the governments.

Our research showed that the EPA is aimed at

mutually strengthening economic collaboration

between nations and it is a considerably important

agreement for the relation between the Association

of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Japan.

Analysis of the current situation revealed that the

EPA framework, accepting foreign nurses in aging

society with declining birth-rate is significant as this

means nurses’ cross-border movement and their

contribution to global community. It is important

that policies concerning movement of people are

made with sufficient mutual decision-making by the

nations.

REFFERENCE

Badan Nasional Penempatan ԁаn Perlindungan Tenaga Kerja

Indonesia (BNP2TKI), 2013, viewed 14 January 2017,

from http://kerja3.com/badan-nasional-penempatan-

dan-perlindungan-tenaga-kerja-indonesia-bnp2tki/

Hirano,O. & Sri,W., 2009, The Japan-Indonesia Economic

Partnership Agreement Through the Eyes of

Indonesian Applicants: A Survey and a Focus Group

Discussion with Indonesian Nurses, Kyushu

University, Fukuoka, 3, pp. 77-90.

Ikai, S., 2010, 病院の世界の理論: Byōin no seiki no riron

[The Theory of the Hospital Century]. Yuhikaku.

Japan International Corporation of Welfare Services

(JICWELS), 2009, About JICWELS, viewed 14 January 2017,

from

http://www.jicwels.or.jp/about/201107/individual2.ht

ml

Kawaguchi, Y., Hirano, O.Y., &Ohno, S., 2009, A national

Survey on Acceptance of Foreign Nurse in Japan’s

Hospitals (1): An outline Results, Kyushu University,

Fukuoka,3, pp. 53-58.

Kawaguchi, Y., Hirano, O.Y., &Ohno, S., 2010, A Nationwide

Survey on Acceptance of foreign Nurses in Japan’s

Hospitals (3): Examination of Regional Differences,

Kyushu University, Fukuoka,5, pp.147-152.

Keohane, R.O., & Nye, J.S., 2012, Power and

interdependence, Minerva Shobo.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), 2009, Economic

Partnership Agreement (EPA) / Free Trade Agreement

(FTA), viewed 4 January 2017, from

http://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/gaiko/fta/index.html

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2017, インドネシア

、フィリピン及びベトナムからの外国人看護師・

介護福祉士候補者の受入れについて [ About

accepting nominees for foreign nurses and nursing

care workers from Indonesia, Philippines,

Vietnam]. viewed 21 December 2017, from

http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/koyou/other22/

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2008, On

medical shortages, viewed 10 January 2017, from

http://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2008/08/dl/s0821-4f.pdf

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2017, EPAに基づ

く外国人看護師候補者の看護師国家試験の結果

[Results of foreign nurse candidate nurse national

examination based on EPA ].viewed 21 December 2017,

from http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/04-Houdouhappyou-

10805000-Iseikyoku-Kangoka/0000157982.pdf

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2013, 経済連携協定

(EPA)に基づく外国人看護師・介護福祉士受入

関係事業[Foreign nurse / care work welfare receiving

business related business based on Economic Partnership

Agreement (EPA)]. viewed 14 January 2017, from

http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou/2r9852000002ycsb-

att/2r9852000002ywku.pdf

Ogawa, R., K, Y., Hirano, O.Y., &Ohno, S., 2010, A

follow up survey on hospitals and long-term care

facilities accepting the first batch of Indonesian

nurse/certified care worker candidates (1) Analysis on

International Labor Migration of Health Care Workers in Japan Under the Economic Partnership Agreement: The Case of Indonesian Nurses

71

the current status and challenges, Kyushu University,

Fukuoka, 5, pp.85-98.

Ogawa, R., K, Y., Hirano, O.Y., & Ohno, S., 2010, A

follow-up survey on hospitals and long-term care

facilities accepting the first batch of Indonesian

nurse/certified care worker candidates (2) An analysis

of various factors related to evaluation of the

candidates and Economic Partnership Agreement

scheme, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, 5, pp. 99-111.

Otsuka, K.&Shiraishi,T., 2010, 国家と発展:Kokka to

keizai hatten [Nation and economic development].

Toyo Keizai Inc.

Sasakawa Peace Foundation, 2009, 始動する外国人材に

よる看護介護の対話:Shidō suru gaikoku jinzai ni

yoru kango kaigo - ukeire-koku to okuridashi-koku no

taiwa [ Nursing and care by foreign workforce to

begin: A dialog between the accepting country and

dispatching country], Sasakawa Peace

Foundation,Tokyo.

The House of Representatoves, Japan, 2006,質問本 文情

報 [Question information].viewed 21 December 2017,

from

www.shugiin.go.jp/internet/itdb_shitsumon.nsf/html/shitsum

on/a165143.htm

Tsukada, N., 2011, 介護現場の労働者日本のケア現場

はどう変わるか:Kaigo genba no gaikokujin rōdōsha

- Nihon no kea genba wa dō kawaru ka [Foreign

workers in the field of nursing care: How will the

nursing care field in Japan change?], Akashi Shoten.

INAHEA 2017 - 4th Annual Meeting of the Indonesian Health Economics Association

72