The Analysis of the Existence of Special Education Teacher in

Inclusive School in Indonesia

Munawir Yusuf, Erma Kumala Sari and Priyono Priyono

University of Sebelas Maret, Jl. Ir. Sutami no 36A, Surakarta, Indonesia

munawiryusuf@staff.uns.ac.id

Keywords: Employment Status, Inclusive School, Recruitment, Regulation, Special Education Teacher, Work

Guideline.

Abstract: The aim of this study is to map the special education teachers’ (SET) problems in inclusive school. This

study used a mixed method research involving 265 SETs as respondents. The variables examined included:

(1) SET regulation, (2) SET recruitment process, (3) SET employment status, (4) SET work guidelines, and

(5) SET competence. Data were collected using a semi-open questionnaire and a competence scale. The data

was analyzed by quantitative and qualitative technique. The results of the study concluded that the existence

of SET in inclusive schools still faced problems in terms of regulation, recruitment, employment status, and

work guidelines. In addition, the ministerial regulation No. 70 / 2009 about inclusive education has not been

implemented optimally in inclusive schools. However, the teachers’ competence (pedagogy, professional,

personality, social, and special education competence) of SETs in inclusive schools in Indonesia are mostly

in good and adequate category. This study suggests that the government immediately organize the

regulation of SET to guarantee the existence of SET in the future.

1 INTRODUCTION

Inclusive education is now becoming an important

topic in education research’s in various countries

(India, Nepal, Pacific region, Canada, South Africa,

Arab, Madrid) around the world (Tilak, 2015;

Maudslay, 2014; Miles and Merumeru, 2014;

McCrimmon, 2014; Ntombela, 2011; Crabtree and

Williams, 2011; Bermejo et al., 2009). Inclusive

education also become the topic of education

researchs in all levels of education (Yusuf et al.,

2017; Mackey, 2014; Sucuoğlu et al., 2013). Many

studies show that implementation of inclusive

education in schools has a positive effect on

students, both students in general and those with

special needs (Waldron and McLesky, 2009; Salend

and Duhaney, 1999). Thus, inclusive education is

believed to be one of the solutions in expanding the

access and improving the quality of education in

schools (Waldron and McLesky, 2009; Salend and

Duhaney, 1999). Many previous researches above

about inclusive education show the importance of

inclusive education and inclusive school as the

topics of education researches.

One important aspect of the inclusive school is

the existence of special education teachers (SET).

Many researches have been done by previous

researchers associated with special education

teachers (Douglas et al., 2016; Vernon-Dotson et al.,

2014; Gehrke and Cocchiarella, 2013; Sindelar,

Brownell, and Billingsley, 2010; Takala et al., 2009;

Waldron, McLeskey, and Pacciano, 2009; Van

Laarhoven et al., 2007). Several studies have

focused on the preparation as SET in inclusive

school (Walker, 2016; McCrimmon, 2014; Vernon-

Dotson et al., 2014; Oyler, 2011; Van Laarhoven et

al., 2009), the role of SET in inclusive school

(Takala et al., 2009), the evaluation of SET in

inclusive school (Woolf, 2014), and the knowledge

of SET in inclusive education (Gehrke and

Cocchiarella, 2013). There is also a research that

discusses the status and future direction of the SET

(Sindelar et al., 2010). This study also discusses the

future direction of the SET. However, this research

is more focused on the analysis of the problems of

SETs (regulation, recruitment process, employment

status, and work guideline) and the competence of

SETs in inclusive schools in Indonesia.

The existence of SETs in regular schools is one

key to make the inclusive education better success.

Legislation in Indonesia explained that each of the

inclusive school is required to have at least one SET

Yusuf, M., Sari, E. and Priyono, P.

The Analysis of the Existence of Special Education Teacher in Inclusive School in Indonesia.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences (ICES 2017) - Volume 2, pages 503-507

ISBN: 978-989-758-314-8

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

503

(Ministry of Education Act No. 70/ 2009). However,

the existence of SETs in inclusive schools has not

been completely protected, both in the employment

status and the career development. There is no

specific regulation governing the existence of SET

clearly. The existing regulation only explains about

the existence of class teachers, subject teachers, and

counseling teachers (Ministry of Empowerment and

Bureacratic Reformation No. 16/2009). In short, the

SET employment status in Indonesia has not been

protected.

Thus, it is necessary to do the assessment and

analysis relating to the existence of the SET in

inclusive schools in Indonesia in terms of the

problems faced and the competence of SET, so the

best solution could be found. Therefore, the study

aims to map the problems of SETs in Indonesia in

five perspectives, namely (1) SET regulations in

inclusive school, (2) SET recruitment process in

inclusive school, (3) SET employment status in

inclusive school, (4) SET work guidelines in

performing their duties in inclusive school, and (5)

SET competence.

2 METHODS

This study employed a mixed methods research

(Creswell, 2009) conducted in May until October

2016. The subjects were 265 SET in inclusive

schools in four districts/cities in Central Java

Indonesia (Surakarta, Boyolali, Salatiga, and

Wonogiri) obtained by purposive random sampling

technique. The research variables examined included

(1) SET regulations; (2) SET recruitment process;

(3) SET employment status; (4) SET work guideline,

and (5) SET competence.

The data were collected by a semi-open

questionnaire (9 quantitative and qualitative

questions) to measure the SET problems in inclusive

schools (regulation, recruitment process,

employment status, and work guideline) and a

competence scale (95 statements) to measure the

SET competencies in inclusive schools

(professional, pedagogic, social, personality, and

special education competence). Validity test results

(range from 0,422 – 0,765) indicated that the scale

was valid, while the reliability test results with

internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha formulation

= 0,751) indicated that the scale was reliable.

Furthermore, the collected data were analyzed using

quantitative and qualitative analysis using trend

analysis and percentage of each of the variables

studied. Qualitative data was used to complete and

explain the quantitative data.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Regulation of Inclusive Education

and SET in Inclusive School

The result showed that there are still 36.1% inclusive

schools which have not had a regulation of inclusive

education, while 63.9% inclusive schools have had

it. However, the legislation in Indonesia regulation

stated that each of the inclusive school is required to

have at least one SET (Ministry of Education Act

No. 70/ 2009). It can be concluded that the existence

of inclusive education in inclusive schools has not

had a strong legislation. Thus, not all of the inclusive

schools get the same service fostering from

government.

Furthermore, 66.0% inclusive schools have not

had a regulation of SET, while only 34.0% inclusive

schools have had the regulation. It can be concluded

that the legislation of inclusive education in

Indonesia which explained that each of the inclusive

school is required to have at least one SET (Ministry

of Education Act No. 70/ 2009) has not been

implemented by all-inclusive schools in Indonesia.

Without a regulation of SET, the existence of SET

will become unclear.

3.2 SET Recruitment Process in

Inclusive School

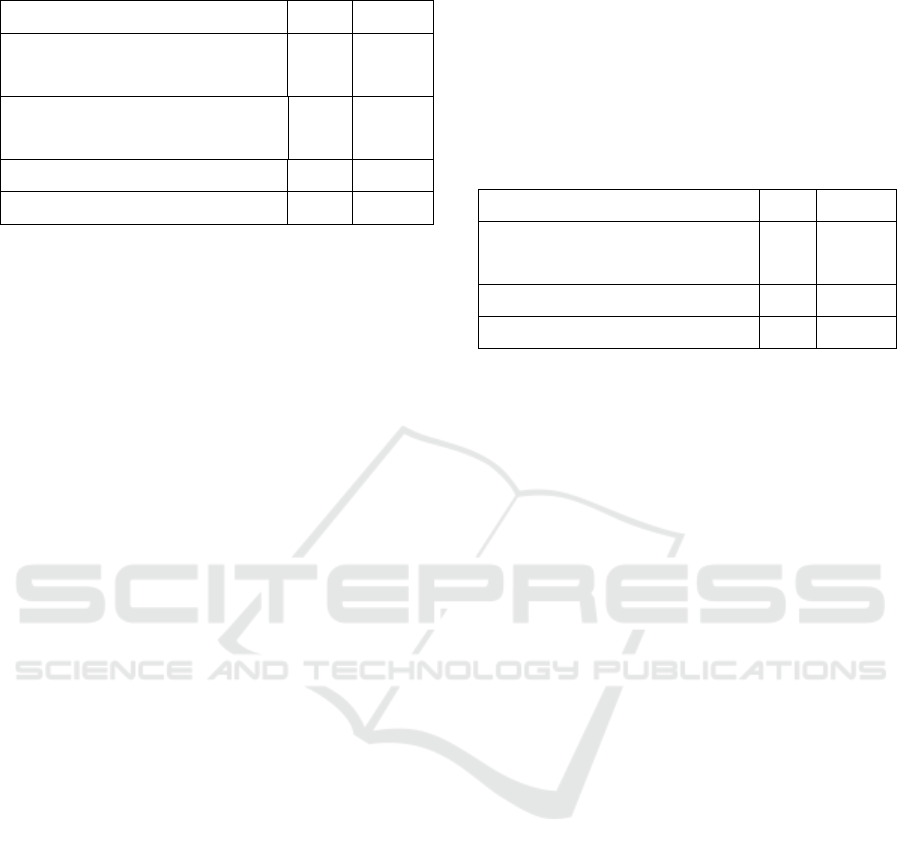

Table 1 showed that most of the SETs (64.9%)

stated that the recruitment process was through the

formation by school (honorary teacher). Meanwhile,

some other SETs stated that the recruitment process

was through the formation by district/city/province

government (9.4%) and through aide-teacher from

special school (2.3%). Some teachers (23.4%) also

added that the recruitment process was through the

additional teaching hours and additional task as SET

(class teacher with additional task). These results

show that the numbers of SET in inclusive schools

who have government employee status are very few.

These findings indicate that the Ministerial

Regulation No 70/ 2009, particularly article 10

which obligates the district/city government to

provide at least one SET in every inclusive school,

has not been implemented optimally.

ICES 2017 - 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences

504

Table 1: SET Recruitment Process.

SET Recruitment Process

Sum

Percent

Formation by district/city/province

government

25

9.4%

Formation by school

(apprentice/part-time teacher)

172

64.9%

Aide-teacher from other schools

6

2.3%

Class teacher with additional task

62

23.4%

In terms of the requirement of SET, the results

show that 78.5% SETs reported had no requirements

demanded to be a SET, while only 21.5% SETs

stated there were some requirements to be a SET.

The requirements as a SET include: (1) graduating

from Special Education Department, (2) having

comprehension and experience of special education,

(3) having a professional background (Occupational

Therapist, Speech Therapy, Physical Therapy, and

Psychology), (4) having experience and being able

to handle children with special needs. In terms of the

SET selection process, the results showed that most

of the SETs (94.0%) stated there was not any a

certain selection process to be a SET, while 6.0%

SETs stated that there was a certain selection

process to be a SET. Thus, most of the SETs in

inclusive schools do not have the qualifications and

competency standards required. This condition is

certainly contrary to the legislation which states that

each teacher is required to have a minimum

qualification of undergraduate degree to meet the

pedagogical, personality, social and professional

competence (Act No. 14 of 2005 on Teachers and

Lecturers).

To be a SET requires specialized professional

education and skills. In the states of the USA like in

Arlington, a bachelor is a minimal qualification of

SET, with specialized skills and sufficient field

experience in dealing with disabilities. License as

SET obtained only from the special education

program accredited by the National Council for

Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). In

developing countries like Vietnam, there are two

categories for the preparation of SET, (1) minimal

undergraduate (S1) or third diploma (D3) of

specialized professional education, or (2) taking

inclusive education program courses with a special

material. Today most of the teacher training colleges

in Vietnam have been offering inclusive education

curriculum at all levels (Nguyet and Thu, 2010).

3.3 SET Employment Status in

Inclusive School

Table 2 shows that the majority of SETs (44.2%) are

civil servant teachers with additional duties as SET;

50.1% SETs are apprentice/part-time teachers; and

5.7% SETs are permanent foundation employees.

Table 2: SET Employment Status.

SET Employment Status

Sum

Percent

Civil servants (with additional

duties as SET)

117

44.2%

Permanent foundation employees

15

5.7%

Apprentice/part-time teachers

134

50.1%

Based on the results, it can be concluded that the

SET employment status is largely the

apprentice/part-time teachers, so they do not get an

adequate salary standards and clear guidance career

as teachers in general. This condition is not

appropriate because the SET has important tasks and

jobs in dealing with special needs children in

inclusive schools (Takala et al., 2009: Pierangelo,

2004; The NCPSE, 2002).

3.4 SET Work Guidelines in Inclusive

School

SET is a special profession which requires certain

qualifications and competence (Act No. 14 of 2005).

As professional, SETs should run their duties based

on standard operating procedure (SOP) according to

the legislation of process standard (Ministry of

Education Act No.22/2016). The results showed that

most of the SETs (51.7%) work with a written

guideline, while 48.3% SETs work without a written

guideline. Most of the SETs who claim to have a

written guideline (81.5%) stated that the guideline

does not meet the requirement of work standard of

SET.

According to Takala et al (2009), SET work

includes three things (1) teaching, (2) consulting

services, and (3) the background work. It is also

explained by Pierangelo (2004) that SET is not only

a direct teaching, but also as paper working and

performing collaboration and consultation. It can be

concluded that SETs have various tasks (Pierangelo,

2004; NCPSE, 2002). Thus, the SET working

guideline in inclusive schools in Indonesia needs to

be clarified with a written guideline, so the SETs can

do their tasks professionally.

The Analysis of the Existence of Special Education Teacher in Inclusive School in Indonesia

505

3.5 SET Competence in Inclusive

School

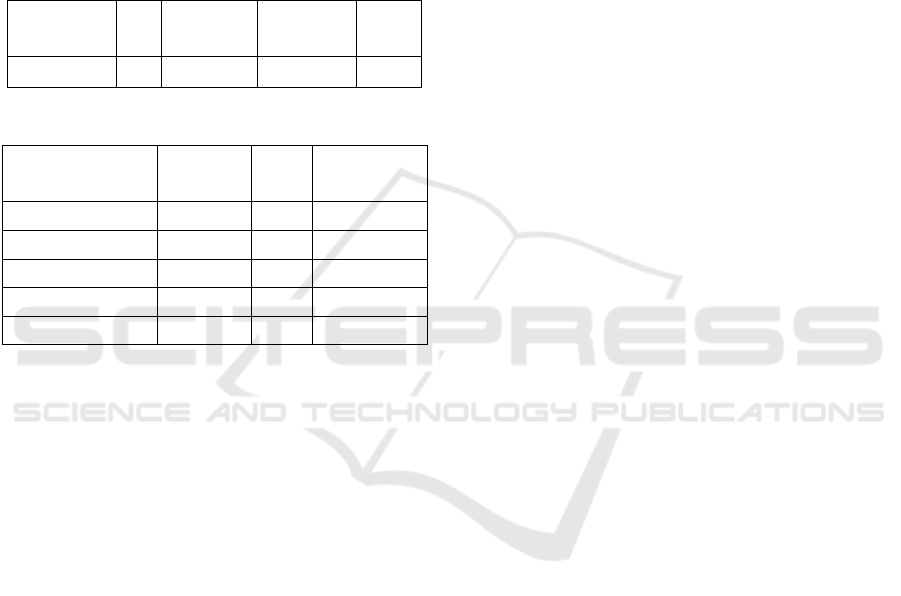

Table 3 showed the descriptive statistic of the SET

competence in inclusive schools. The mean score of

SET competence is 293.95, with minimum score

149.00 and maximum score 419.00. Based on

analysis of categorization refers to the normal curve,

the score can be divided into five categories,

excellent, good, adequate, less and very less.

Table 3: The Descriptive Statistic of SET Competence.

N

Minimum

score

Maximum

score

Mean

Competence

265

149.00

419.00

293.95

Table 4: SET Competence Category.

SET Competence

Category

Range

Score

Sum

Percent (%)

Least

95 – 114

0

0.0

Less

115 – 200

7

2.6

Adequate

201 – 275

85

32.1

Good

276 – 351

143

54.0

Excellent

352 – 475

30

11.3

Table 4 showed that most of the SETs (54%) had

good competence; 32.1% SETs had adequate

competence, 11.3% respondents had excellent

competence, and only 2.6% respondents had less

competence. It can be concluded that the

competence SET (professional competence,

pedagogy, personality, social, and special education

competence) in inclusive schools in Indonesia are

mostly in good categories. The result of this research

has progressed slightly as compared to previous

studies (Martika et al., 2016; Gunarhadi et al., 2016;

Gunarhadi et al., 2012). Gunarhadi et al. (2016)

found that the level of knowledge and pedagogical

skills of SETs in 3 districts of Central Java are in

average and good category. The SET competence in

this study is still better than the regular teacher

competence, especially in special education

competence (Martika et al., 2016).

According to the act (Teacher Act No. 14/ 2005),

teacher should have 4 kinds of basic competencies

(pedagogical, personality, social and professional

competence). These results indicated that although

the employment status of SETs was still unclear, but

they still showed professional performances.

Therefore, their status must be recognized and

protected. They hope that their career in the future

will be recognized as well as teachers in general.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The results of the study concluded that (1) the

existence of SET in inclusive schools still faced with

problems in terms of regulation, recruitment,

employment status, and work guideline, (2) the

ministerial regulation No. 70/2009 about inclusive

education has not been implemented optimally in

inclusive schools, (3) the competence (pedagogy,

professional, personality, social, and special

education competence) of SETs in inclusive schools

in Indonesia are mostly in good and adequate

category. Therefore, special regulations of SET in

Indonesia must be drafted, so the existence and the

future of SET in inclusive schools in Indonesia can

be more protected as well as teachers in general and

the SET are able to work more professionally in

inclusive schools.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors acknowledge Program Unggulan Perguruan

Tinggi Negeri (PUPT) from RISTEK DIKTI.

REFERENCES

Bermejo, V. S., Castro, F. V., Martínez, F. M., Góngora,

D. P., 2009. Inclusive education in Spain: Developing

characteristics in Madrid, Extremadura and Andalusia.

Research in Comparative and International

Education. 4(3), 321-333.

Crabtree, S. A., Williams, R., 2013. Ethical implications

for research into inclusive education in Arab societies:

Reflections on the politicization of the personalized

research experience. International Social Work. 56(2),

148-161.

Creswell, J. W., 2009. Research Design: Qualitative,

Quantitative, and Mixed Method Approaches, Sage

Publication. USA,

3rd

edition.

Douglas, S. N., Chapin, S. E., Nolan, J. F., 2016. Special

Education Teachers, Experiences Supporting and

Supervising Paraeducators, Implication for Special

and General Eucation Settings. The Journal of

Teacher Education Division of the Council for

Exceeptional Children. 39(1), 60 – 70.

Gehrke, R. S., Cocchiarella, M., 2013. Preservice special

and general educators’ knowledge of inclusion.

Teacher Education and Special Education: The

ICES 2017 - 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences

506

Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the

Council for Exceptional Children. 36(3), 204-216.

Gunarhadi, Sugini, Andayani, T. R., 2012. Teachers’

Performance in Inclusive Education. Procedia-Asean

Academic Community International Conference. HS-

36-PF, 48-51.

Gunarhadi, Sunardi, Andayani, T. R., Anwar, M., 2016.

Pedagogic mapping of teacher competence in

inclusive schools. Procedia International Conference

of Teacher Training Education. 1(1), 389-394.

Mackey, M., 2014. Inclusive Education in the United

States: Middle School General Education Teachers’

Approaches to Inclusion. International Journal of

Instruction. 7(2), 5-21.

Martika, T., Salim, A., Yusuf, M., 2016. Understanding

Level of Regular Teachers’ Competency

Understanding to Children with Special Needs in

Inclusive School. European Journal of Special

Education Research. 1(3), 30-38.

Maudslay, L., 2014. Inclusive education in Nepal:

Assumptions and reality. Childhood. 21(3), 418-424.

McCrimmon, A. W., 2014. Inclusive Education in Canada:

Issues in Teacher Preparation. Intervention in School

and Clinic. 50(4), 234-237.

Miles, S., Lene, D., Merumeru, L., 2014. Making sense of

inclusive education in the Pacific region: Networking

as a way forward. Childhood. 21(3). 339-353.

Nguyet, D. T., Thu, H. L., 2010. How to Guide Preparing

Teachers for Inclusive Education, Chatolic Relief

Services. Vietnam.

Ntombela, S., 2011. The progress of inclusive education in

South Africa: Teachers’ experiences in a selected

district, KwaZulu-Natal. Improving Schools. 14(1), 5-

14.

Oyler, C., 2011. Teacher preparation for inclusive and

critical (special) education. Teacher Education and

Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher

Education Division of the Council for Exceptional

Children. 34(3), 201-218.

Peraturan Menteri Pendidikan Nasional (Permendiknas)

Nomor 70, 2009. tentang Penyelenggaraan

Pendidikan Inklusif.

Permenpan dan Reformasi Birokrasi Republik Indonesia

Nomor 16, 2009. tentang Jabatan Fungsional Guru

dan Angka Kreditnya.

Pierangelo, R., 2004. The Special Educator’s Survival

Guide, Jossey-Bass. San Fransisco.

Salend, S. J., Dunhaney, L. M. G., 1999. The Impact of

Inclusion on Students With and Without Disabilities

and Their Educator. Journal of Remedial and Special

Education. 20(2), 114 – 126.

Sindelar, P. T., Brownell, M. T., Billingsley, B., 2010.

Special education teacher education research: Current

status and future directions. Teacher Education and

Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher

Education Division of the Council for Exceptional

Children. 33(1), 8-24.

Sucuoğlu, B., Bakkaloğlu, H., Karasu, F. İ., Demir, Ş.,

Akalın, S., 2013. Inclusive preschool teachers: Their

attitudes and knowledge about inclusion. International

Journal of Early Childhood Special Education. 5(2),

107-128.

Takala, M., Pirttimaa, R., Törmänen, M., 2009.

RESEARCH SECTION: Inclusive special education:

the role of special education teachers in Finland.

British Journal of Special Education. 36(3), 162-173.

The NCPSE (National Clearinghouse for Professions

Sspecial Education), 2002. Special Education

Teacher, Making a Difference in the Lives of Students

with Special Needs, Council for Exceptional Children.

Arlington.

Tilak, J. B., 2015. How Inclusive Is Higher Education in

India? Social Change. 45(2), 185-223.

Undang – Undang Nomor 14, 2005. tentang Guru dan

Dosen.

Van Laarhoven, T. R., Munk, D. D., Lynch, K., Bosma, J.,

Rouse, J., 2007. A model for preparing special and

general education preservice teachers for inclusive

education. Journal of Teacher Education. 58(5), 440-

455.

Vernon-Dotson, L. J., Floyd, L. O., Dukes, C., Darling, S.

M., 2014. Course delivery: Keystones of effective

special education teacher preparation. Teacher

Education and Special Education: The Journal of the

Teacher Education Division of the Council for

Exceptional Children. 37(1), 34-50.

Waldron, N. L., McLeskey, J., Pacchiano, D., 2009.

Giving teachers a voice: Teachers' perspectives

regarding elementary inclusive school programs (ISP).

Teacher Education and Special Education: The

Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the

Council for Exceptional Children. 22(3), 141-153.

Walker, Z., 2016. Special Education Teacher Preparation

in Singapore’s Dual Education System. Teacher

Education and Special Education: The Journal of the

Teacher Education Division of the Council for

Exceptional Children. 39(3), 178-190.

Woolf, S. B., 2014. Special Education Professional

Standards How Important Are They in the Context of

Teacher Performance Evaluation?. Teacher Education

and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher

Education Division of the Council for Exceptional

Children. 38(4), 276-290.

Yusuf, M., Sugini, Choiri, S., Rejeki, D. S., 2017.

Development of inclusive education course at the

faculty of teacher training and education Universitas

Sebelas Maret. International Journal for Studies on

Children, Women, Elderly, and Disabled. 1, 121-126.

The Analysis of the Existence of Special Education Teacher in Inclusive School in Indonesia

507